The Ear

Basic concepts

Anatomy and physiology

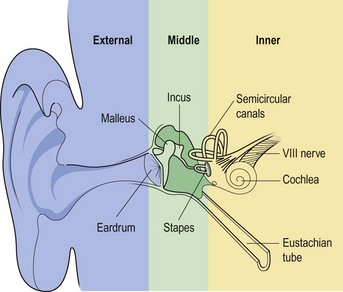

Structurally, the ear has three parts (Fig. 1.1):

The external ear

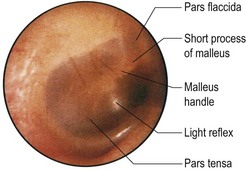

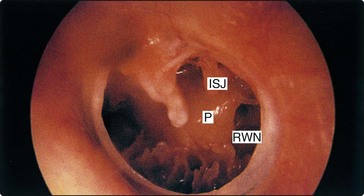

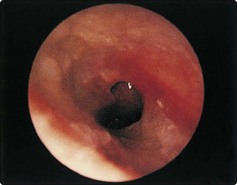

The eardrum is the window of the middle ear and is divided into the pars tensa and pars flaccida. The main landmark on the drum is the malleus handle (Fig. 1.2).

The middle ear

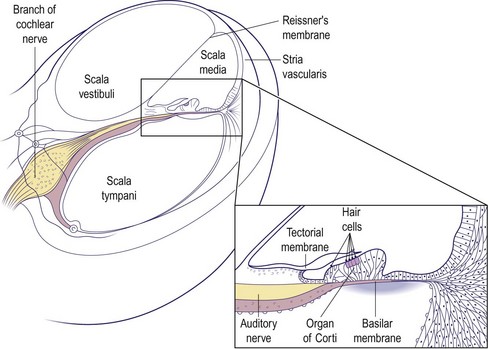

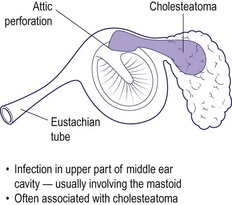

The middle ear is an air-containing space connected to the nasopharynx via the Eustachian tube. It acts as an impedance matching device to transfer sound energy efficiently from air to a fluid medium in the cochlea (Fig. 1.3). The middle ear space, including the mastoid air cells, is closely related to the temporal lobe, cerebellum, jugular bulb and labyrinth of the inner ear. The space contains three ossicles (the malleus, incus and stapes) which transmit sound vibrations from the eardrum to the cochlea. The middle ear also contains two small muscles and is traversed by the facial nerve before it exits the skull.

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms

History taking in ear complaints should be brief but thorough. Table 1.1 provides a reference guide of the major points that should be covered. The otological symptoms are discussed in greater detail later in this section, but it is important to establish the predominant complaint and whether it affects one or both ears.

Table 1.1 Major points in history taking in patients with an otological complaint

| Otological | Nasal |

| Hearing loss – onset and rate of progression | Obstruction, discharge, etc. |

| Otalgia | |

| Otorrhoea | Drugs |

| Tinnitus | Ototoxic agents (e.g. aminoglycosides) |

| Imbalance | |

| Family history | |

| Noise exposure | Hearing loss |

| Previous ear surgery |

Signs

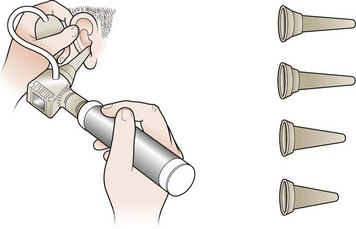

Satisfactory examination cannot be undertaken without adequate lighting. Battery auriscopes with a fibre or glass ring light give a coaxial beam with bright uniform illumination. A pneumatic attachment tests the mobility of the eardrum (Fig. 1.4).

The pinna should be examined for scars and signs of crusting or weeping. Before introducing the auriscope, the ear canal must be straightened by elevating the pinna upwards and backwards (Fig. 1.4). The condition of the ear canal should be noted before the eardrum is examined. If an adequate seal of the canal is achieved by the speculum, gentle pressure on the pneumatic bulb will move the eardrum if the middle ear contains air. This is helpful in distinguishing perforations from thin or translucent segments.

A complete examination also involves viewing the Eustachian tube orifice in the nasopharynx.

Clinical tests of hearing

Tuning fork tests

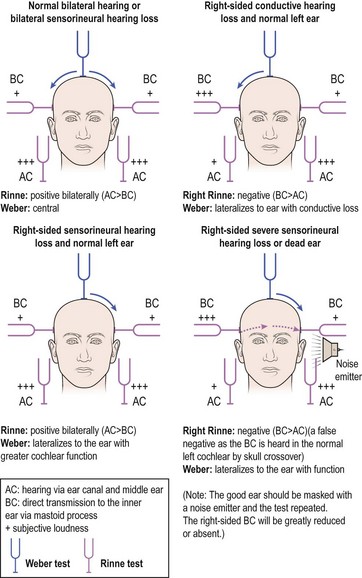

Rinne test

The Rinne test compares air conduction (AC – hearing via ear canal and middle ear) with bone conduction (BC – direct transmission to the inner ear via the mastoid process). The examiner holds the fork by the ear canal and then places it on the mastoid process using gentle counterpressure with the other hand. The patient is asked which position of the fork sounds louder: in front of the ear or touching the mastoid (Fig. 1.5).

Audiometry, vestibulometry and radiology

Audiometry

Subjective tests

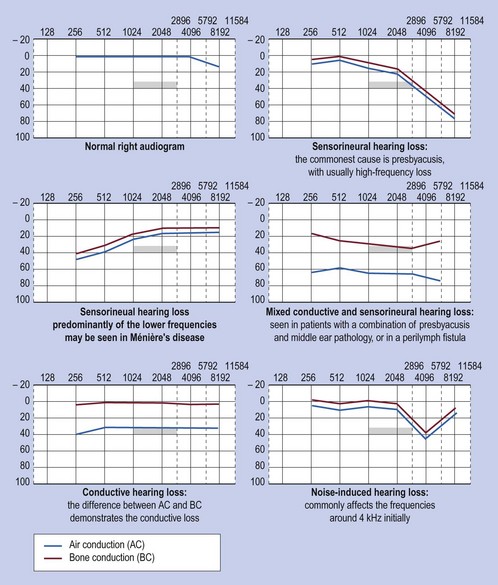

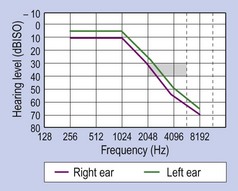

Pure tone audiograms are a standard means of recording hearing levels. Using headphones, each ear is tested individually for air conduction and, if necessary, bone conduction thresholds. The results are usually plotted as a graph. A result of 0 dB (decibels) is the average normal threshold for hearing in young adults (Fig. 1.6).

Objective tests

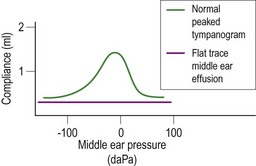

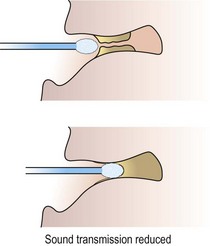

Impedance audiometry is an extremely useful test in the diagnosis of middle ear disease and some types of sensorineural hearing loss. By varying the pressure in the external ear canal, the compliance (i.e. mobility) of the eardrum may be calculated by the degree of sound reflected from a probe tone. This is very useful when screening for middle ear effusions, particularly in children, and for assessing Eustachian tube function (p. 7). It can also test the integrity of the middle ear mechanism and the auditory reflex arc (stapedius reflex).

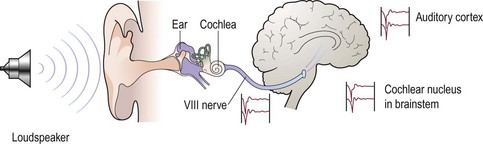

Electric response audiometry (ERA) (Fig. 1.7) is another objective test. An evoked potential in the eighth nerve, brainstem or auditory cortex may be recorded using skin electrodes following acoustic stimulation of the cochlea. This principle is used to objectively assess hearing thresholds where the standard tests are not applicable, e.g. babies, disabled people and suspected malingerers.

Vestibulometry

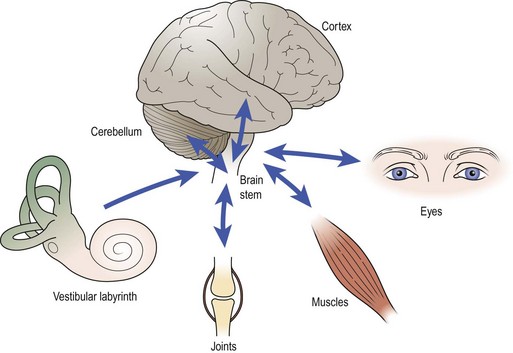

The vestibule has three parts: the utricle, the saccule and the semicircular canals (see Fig. 1.1, p. 2). Each vestibule tonically discharges information to the brain regarding head position, and linear and angular acceleration. This information is part of the general proprioceptive input (joint, tendon, skin and ocular inputs). Dysequilibrium may be the result of an abnormal input from any part of the proprioceptive sensors, or a dysfunction of the central nervous connection secondary to disease, e.g. ischaemia or demyelination.

Tests

Positional test

From an erect sitting position on a couch, the patient lies flat with the head turned to one side and below horizontal (Fig. 1.8). The onset of any vertigo is noted and the eyes are observed for nystagmus. The feeling of movement and the nystagmus, if present, are allowed to settle before the patient sits upright. The manoeuvre is repeated with the head to the opposite side. This test may help to distinguish vertigo caused by peripheral (otological) as opposed to central pathologies.

Rotation tests and electronystagmography

Rotational tests assess the vestibular response to angular acceleration by measuring nystagmus from surface electrodes around the ocular muscles. Various other tests of eye pivot, optical fixation and suppression of nystagmus may be recorded by electronystagmography. These investigations give information about central mechanisms and disorders of the vestibular nuclei in the brainstem (p. 20).

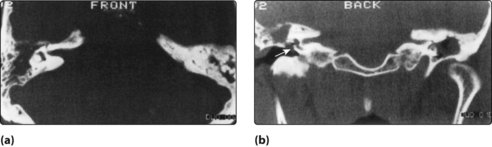

Radiology

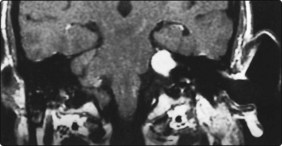

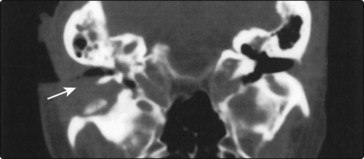

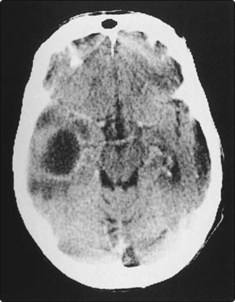

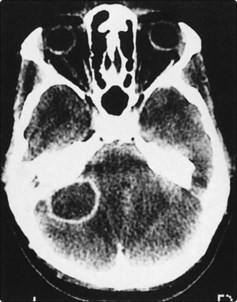

Modern CT scanning and MRI are now widely used to provide information on otitis media with complications, and in the diagnosis of acoustic neuromas (Figs 1.9 and 1.10). MRI is particularly useful in assessing the extent of vascular lesions such as glomus jugulare tumours, and in visualizing the acoustic nerve.

Audiometry, vestibulometry and radiology

Correctly performed pure tone audiograms are the most reliable method of assessing hearing thresholds.

Correctly performed pure tone audiograms are the most reliable method of assessing hearing thresholds.

Electric response audiometry may be required in assessing the thresholds in very young infants and others who are unable to respond to subjective audiometric tests.

Electric response audiometry may be required in assessing the thresholds in very young infants and others who are unable to respond to subjective audiometric tests.

Impedance audiometry is extremely useful in assessing the presence of middle ear effusions.

Impedance audiometry is extremely useful in assessing the presence of middle ear effusions.

A patient with a positive fistula test in the presence of chronic ear disease requires urgent otological referral.

A patient with a positive fistula test in the presence of chronic ear disease requires urgent otological referral.

Hearing loss – general introduction and childhood aetiology

General introduction

A hearing loss, as mentioned previously, can be conductive, sensorineural or mixed. Any disease affecting the outer or middle ear will produce a conductive deafness. Sensorineural loss results from damage to the cochlea or eighth nerve. The degree of hearing loss can be quantified on an audiogram with the thresholds of hearing quoted in decibels (p. 4).

Table 1.2 lists the most common causes of hearing loss. Most of those leading to a conductive deafness will be evident from history, otoscopy, tuning fork tests and audiometry. However, the aetiology of sensorineural loss is frequently unclear. In these cases, specific points in the history should be determined. These points are listed in Table 1.3.

| Cause | Conductive hearing loss | Sensorineural hearing loss |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital | Atresia of ear, ossicular abnormalities | Prenatal: genetic, rubella |

| Acquired | External: wax, otitis externa, foreign body | Perinatal: hypoxia, jaundice |

| Middle ear: middle ear effusion, chronic otitis (cholesteatoma, perforated drum), otosclerosis, traumatic perforation of drum (ossicular disruption) | Trauma: noise, head injury, surgery | |

| Inflammatory: chronic otitis, meningitis, measles, mumps, syphilis | ||

| Degenerative: presbyacusis | ||

| Ototoxicity: aminoglycosides, cytotoxics | ||

| Neoplastic: acoustic neuroma | ||

| Idiopathic: Ménière’s disease, sudden deafness |

Table 1.3 Points to cover in clinical history of a patient presenting with hearing loss

Hearing loss in children

The incidence of severe sensorineural deafness is about 1 in 1000. Half of these children have a hereditary type of deafness (Fig. 1.11). The others have hearing losses resulting from acquired causes. Even mild degrees of hearing loss, either conductive or sensorineural, can impair learning ability.

Childhood hearing loss should be suspected in certain groups of individuals (Table 1.4). Children falling into these risk categories should be referred to an audiological physician or otologist for audiometric assessment. This is often a multidisciplinary approach using teachers of the deaf and speech therapists in the same clinic. If a hearing loss can be overcome at an early age, particularly severe sensorineural losses, there is a greater chance the child can attend an ordinary school. Where a hereditary loss is confirmed, a geneticist may advise on risks to future children.

Table 1.4 The childhood groups at risk of suffering from hearing loss

History taking from the parents should concentrate on establishing the answers to specific questions, as well as making a general otological assessment (Table 1.5). Most hearing problems relate to middle ear disease. However, sensorineural deafness may coexist.

Table 1.5 History taking in childhood hearing loss

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear)

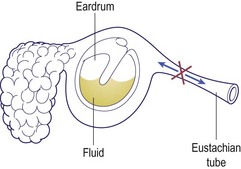

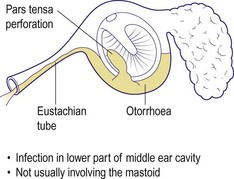

The effusion in the middle ear may be serous, mucoid or thick (glue). The aetiology is usually Eustachian tube dysfunction, where normal ventilation of the middle ear is disturbed (Fig. 1.12). A diagnosis of chronic otitis media with effusion is made when fluid is present behind the eardrum for 12 weeks or more.

Clinical features

Children with OME usually present with hearing loss or recurrent otalgia. Children with a cleft palate or Down’s syndrome have a higher incidence of middle ear effusions. The otoscopic features of OME are characteristic (Fig. 1.13).

The hearing loss is conductive and may fluctuate down to as much as 40 dB. Tympanometry produces a flat trace, indicating an immobile drum (Fig. 1.14).

Treatment

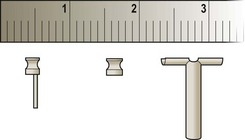

There is as yet no effective long-term medical treatment for established OME. Short-term improvements with antibiotics are not sustained. Decongestant mixtures are ineffective. If the effusion persists, surgery may be required to restore hearing. Removal of the adenoids reduces the incidence of recurrent effusions. Myringotomy, aspiration of fluid and insertion of a ventilation tube (grommet) immediately restores the hearing (Fig. 1.15). Grommets may remain in the drum for up to 12 months before being extruded. After grommet extrusion some children require reinsertion due to recurrent or persisting middle ear effusions.

Otorrhoea after grommets

Hearing loss – general introduction and childhood aetiology

Childhood hearing loss needs early detection to maximize speech and language acquisition.

Childhood hearing loss needs early detection to maximize speech and language acquisition.

Screening at 7–8 months used to be mandatory. Test failure requires early referral.

Screening at 7–8 months used to be mandatory. Test failure requires early referral.

Neonatal screening with otoacoustic emissions is now universal in the UK.

Neonatal screening with otoacoustic emissions is now universal in the UK.

Middle ear effusions are common, and may be detected by pneumatic otoscopy.

Middle ear effusions are common, and may be detected by pneumatic otoscopy.

OME may present with otalgia, or may be asymptomatic until hearing loss is suspected.

OME may present with otalgia, or may be asymptomatic until hearing loss is suspected.

Insertion of grommets is required for persistent otitis media with effusion.

Insertion of grommets is required for persistent otitis media with effusion.

Otorrhoea due to infected grommets usually resolves with topical treatments.

Otorrhoea due to infected grommets usually resolves with topical treatments.

Hearing loss – adult aetiology

Conductive hearing loss

Ear canal

Wax production varies between individuals and races. Blind attempts to remove wax with cotton buds usually result in impaction. Wax may be properly removed by syringing the ear or with a blunt hook (p. 25). Preliminary softening can be achieved with sodium bicarbonate eardrops three times a day, or hydrogen peroxide. Rarely, excessive accumulations of desquamated skin and wax in the deepest part of the external meatus can expand and erode the ear canal. This is termed keratosis obturans, and an anaesthetic may be required to remove it.

The external canal may be narrowed by bony exostoses predisposing to keratin accumulation (Fig. 1.16). These exostoses often occur in swimmers and require no treatment unless they cause external otitis or hearing deficits.

Eardrum and middle ear

Perforations of the eardrum can occur from trauma and acute or chronic otitis media (Fig. 1.17). The degree of hearing loss depends on the site of the perforation and the extent of middle ear disease.

Adults may suffer with middle ear effusions, although less commonly than children. Investigations should rule out sinusitis, or nasopharyngeal tumours blocking the Eustachian tube (see Fig. 1.12, p. 7).

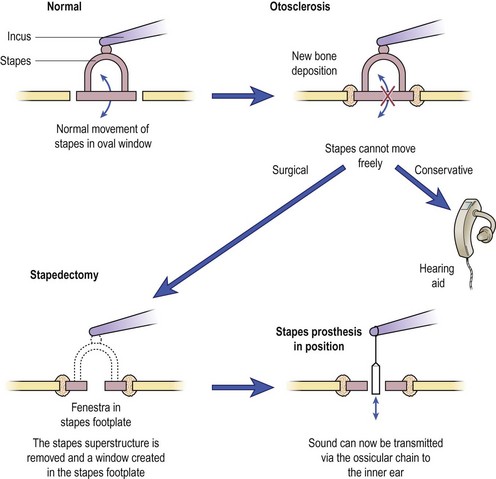

Otosclerosis is a disease where new bone growth occurs in the capsule of the inner ear. This may fix the footplate of the stapes. Hearing loss characteristically develops in the young adult and is usually conductive (p. 3), although the otoscopic appearance of the eardrum is normal. Pregnancy can accelerate the symptoms, suggesting a hormonal association with the disease. A family history is frequently elicited. Tinnitus may also be present.

Surgery for otosclerosis may restore normal hearing but also carries a small risk of total hearing loss. Use of a hearing aid has no complications, but is often refused (Fig. 1.18).

Sensorineural hearing loss

Presbyacusis (common)

Presbyacusis is a progressive loss of hair cells in the cochlea with age. Roughly 1% of cells are lost each year, and this affects the high-frequency part of the inner ear first (Fig. 1.19). It becomes clinically noticeable from the age of about 60–65 years. The degree of loss varies, as does the age of onset. Some patients with presbyacusis have recruitment (reduced dynamic range of hearing) which reduces effective amplification. The threshold for hearing and the uncomfortable level of sound are abnormally close (e.g. ‘Speak up, I can’t hear you … don’t shout so loud!’). Discrimination may also be affected (‘I hear you but can’t understand you’). There is no treatment to prevent this loss. When a significant social or work handicap is present, a hearing aid may be prescribed. This should be digital so that the pattern of amplification is tailored to the pattern of the individual’s hearing loss. Two hearing aids are better than one, because of binaural hearing.

Acoustic tumours

Acoustic tumours are rare, but treatable, tumours of the vestibular element of the eighth cranial nerve. The most common presentation is a progressive unilateral hearing loss with tinnitus. MRI scanning with gadolinium is the investigation of choice and can demonstrate small tumours (Fig. 1.20). Current treatment options include serial scanning (for small tumours), surgical excision or stereotactic radiosurgery.

Non-organic hearing loss

Hearing loss – adult aetiology

Wax impaction and presbyacusis are the leading causes of hearing loss in adults.

Wax impaction and presbyacusis are the leading causes of hearing loss in adults.

Most causes of conductive hearing loss are identifiable on otoscopy.

Most causes of conductive hearing loss are identifiable on otoscopy.

Otitis media with effusion in adults is rare, so exclude neoplasia of the nasopharynx.

Otitis media with effusion in adults is rare, so exclude neoplasia of the nasopharynx.

In otosclerosis the eardrum has a normal appearance.

In otosclerosis the eardrum has a normal appearance.

A progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing loss should be fully investigated to exclude an acoustic neuroma.

A progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing loss should be fully investigated to exclude an acoustic neuroma.

Aids to hearing

Hearing loss is a major disability that can interfere with the social, work and educational spheres of a patient’s life. A 35 dB loss in the speech frequencies (500–2000 Hz) can result in major problems. Fortunately, the majority of sufferers may be helped by employing one or more of the remedies available (Table 1.6).

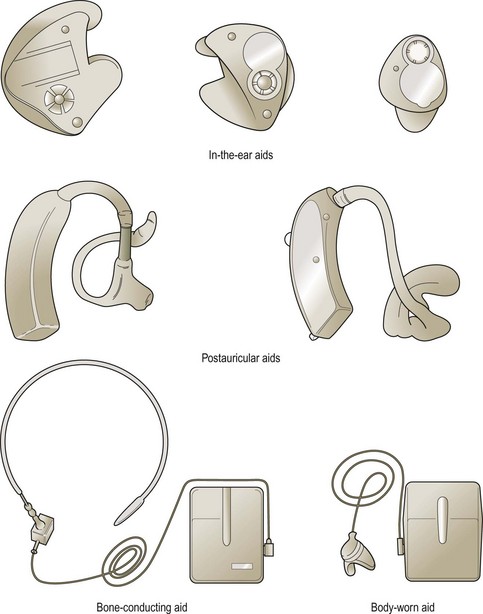

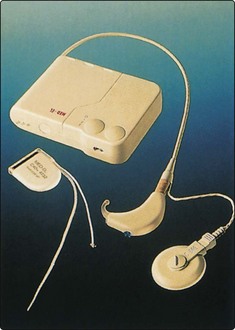

Electronic hearing aids

A variety of aids is shown in Figure 1.21. The majority of patients will be fitted with a postauricular hearing aid which is relatively unobtrusive. However, severe hearing loss may only be assisted by body-worn (BW) aids. It is possible to incorporate the aid into a spectacle frame if desired. Miniaturized aids can also be worn in the ear or inserted into the ear canal.

Problems with electronic hearing aids

The common problems encountered with electronic aids are listed in Table 1.7. Probably the most frequent difficulty is with acoustic feedback. This produces the familiar high-pitched whistle and is particularly seen in patients who require high amplification, and in whom the ear mould allows sound to escape into the microphone. A similar event will occur if the mould is incorrectly inserted, as is frequently seen in elderly people suffering from arthritic joints.

| Problem | Cause |

|---|---|

| Feedback | Badly fitting ear mould |

| Otorrhoea | Ear infection |

| Allergy to mould | |

| No sound | Dead battery |

| Blocked tube |

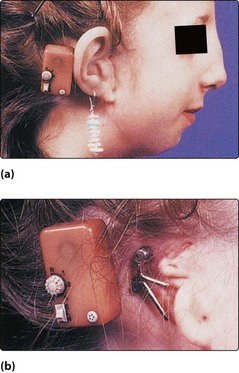

More recent alternatives are bone conduction aids that are anchored in the temporal bone. The external stimulator sets the aid in vibration either across the intervening skin or by a direct percutaneous attachment facility (Fig. 1.22; Fig. 1.53, p. 24). Such aids do not suffer the feedback problems of conventional air conduction aids and also have the advantage of greatly reduced background noise.

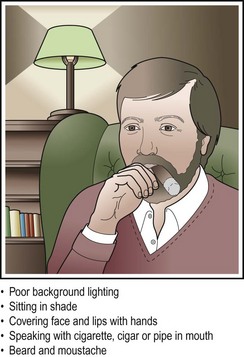

Lipreading and manual communication

Most patients with hearing loss requiring aiding will benefit from the development of lipreading skills. These are essential in any severe or progressive hearing loss. Special classes are run by most hearing aid departments. A deafened person is better able to lipread if the speaker assists in ensuring certain optimal conditions (Fig. 1.23).

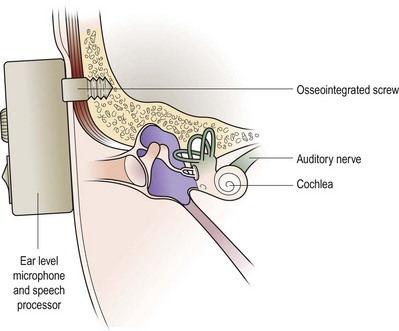

Cochlear implants

A cochlear implant is a device used in patients with a non-functioning cochlea but who have a normal cochlear nerve. Unaidable bilateral sensorineural deafness is the main criterion for potential implantation. The nerve can be stimulated by placing an electrode into the cochlea (Fig. 1.24). A processor converts speech into electrical signals that are transmitted to the electrode. The cochlear nerve is stimulated, giving clues to frequencies and cadences. With modern sound processors a severely deafened individual can be trained to communicate with a very high degree of success.

Organizations for the deaf

Aids to hearing

Hearing aids do not produce normal hearing.

Hearing aids do not produce normal hearing.

Only appropriate aids for the patient’s hearing loss, correctly used, will provide any benefit.

Only appropriate aids for the patient’s hearing loss, correctly used, will provide any benefit.

Environmental aids are extremely valuable.

Environmental aids are extremely valuable.

Lipreading should be instituted early rather than late.

Lipreading should be instituted early rather than late.

Providing a deaf person with the optimal conditions will enable them to lipread.

Providing a deaf person with the optimal conditions will enable them to lipread.

Manual communication is only possible with both parties having the requisite skills.

Manual communication is only possible with both parties having the requisite skills.

Cochlear implants are suitable for only very few patients with bilateral profound hearing loss when a hearing aid is inadequate; implants cannot reproduce speech.

Cochlear implants are suitable for only very few patients with bilateral profound hearing loss when a hearing aid is inadequate; implants cannot reproduce speech.

Otalgia

Otological causes of otalgia

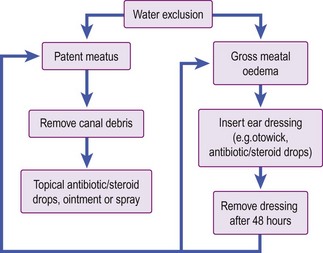

Acute otitis externa

Treatment is outlined in Figure 1.25. A very convenient ear dressing is the otowick, which after insertion into the ear canal will expand if topical drops are applied. Discharge should be sent for culture. Relapse is often due to residual debris in the meatus. Prolonged use of antibiotic/steroid drops promotes secondary fungal otitis, e.g. Aspergillus (see Fig. 1.30, p. 14). Itching may be controlled by 1% hydrocortisone cream applied with a cotton bud, but only after the infection has been treated.

Malignant otitis externa

CT and isotope scanning provide information on the extent of the osteomyelitis (Fig. 1.26). Treatment comprises local aural toilet and insertion of wicks impregnated with an antipseudomonal accompanied by high-dose antibiotics. Surgery for debridement may be necessary in patients in whom the disease progresses despite conservative treatment.

Acute otitis media

Acute otitis media is a common cause of severe otalgia in children. Inflammation of the middle ear cleft usually follows an upper respiratory tract infection which ascends via the Eustachian tube. The eardrum becomes retracted as the tube is blocked, and an inflammatory middle ear exudate develops. Pressure in the middle ear produces severe pain, and the eardrum becomes congested and bulging (Fig. 1.27). At this stage the patient is quite unwell, with fever and tachycardia. Eardrum rupture may then occur, producing a bloodstained discharge with relief of the pain.

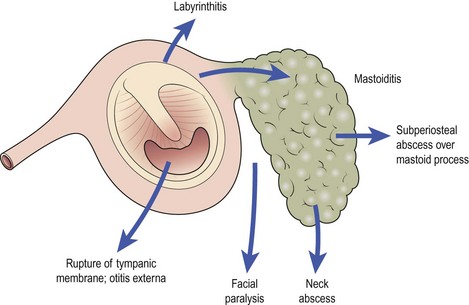

The complications of otitis media usually arise from inadequate treatment or non-compliance. Inflammation of the mastoid air cell system often occurs with acute otitis media, and is controlled with antibiotics. However, suppuration in the mastoid (acute mastoiditis) is serious and potentially life threatening (see Fig. 1.36, p. 16).

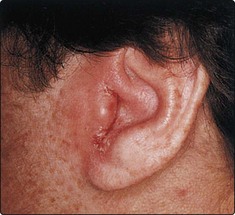

Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome)

The facial nerve ganglion may be affected by shingles. This produces severe pain, with vesicles in the ear canal and on the concha, and is frequently accompanied by facial palsy (see Fig. 1.44, p. 19). Administration of antivirals such as famciclovir or aciclovir, if the vesicles are recognized early, may prevent permanent damage to the facial nerve.

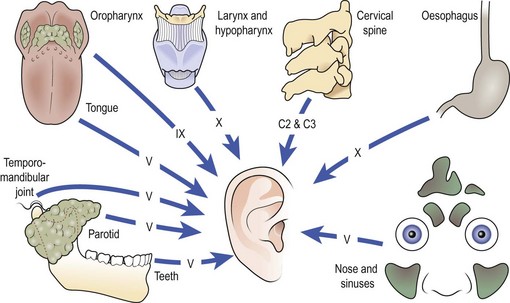

Non-otological causes of otalgia

The ear has a rich sensory supply from several cranial nerves (trigeminal, glossopharyngeal and vagus) and the posterior roots of the second and third cervical nerves. If examination of the pinna, ear canal and eardrum is normal, otalgia is a referred pain. It is important, therefore, to examine the peripheral areas innervated by these nerves (Fig. 1.28).

Referred otalgia in adults

Otalgia

Otalgia may be due to otological or non-otological causes. If the ear is normal, look at distant sites.

Otalgia may be due to otological or non-otological causes. If the ear is normal, look at distant sites.

In children, acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion and a negative middle ear pressure are the most frequent otological causes of otalgia.

In children, acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion and a negative middle ear pressure are the most frequent otological causes of otalgia.

In adults, the temporomandibular joint and cervical spine are common sites of referred otalgia.

In adults, the temporomandibular joint and cervical spine are common sites of referred otalgia.

Never forget neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract as a cause of referred otalgia in adults.

Never forget neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract as a cause of referred otalgia in adults.

Otorrhoea

Otorrhoea – an aural discharge – may arise from diseases of the ear canal, but is more commonly associated with middle ear infections. Patients with otorrhoea usually have a degree of hearing loss (p. 6) but may experience no pain. Soft wax can be mistaken for a discharge, but, at the other extreme, daily offensive otorrhoea may be ignored by some patients with a serious underlying middle ear disease. The character of the discharge provides clues to the aetiology (Table 1.8).

Table 1.8 Characteristics of otorrhoea in relation to aetiology

| Character of otorrhoea | Potential aetiology |

|---|---|

| Watery | Eczema of the ear canal, cerebrospinal fluid (rare) |

| Purulent | Acute otitis externa, furunculosis |

| Mucoid* | Chronic suppurative otitis media (tubotympanic) with a perforation |

| Mucopurulent/bloody | Trauma, acute otitis media, carcinoma of the ear (rare) |

| Foul smelling | Chronic suppurative otitis media (atticoantral) with cholesteatoma |

*Mucous glands are located only in the middle ear.

Otorrhoea from ear canal disease

Acute otitis externa

Acute infection of the external ear canal has already been discussed (p. 12). Although otalgia is the predominant symptom, some degree of otorrhoea is common (Fig. 1.29). It is not unusual for certain general skin conditions to cause otitis externa with otorrhoea, e.g. psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis and eczema. It is useful to emphasize that early relapse after treatment with eardrops is usually due to inadequate aural toilet, or colonization of the canal by a secondary fungal growth (Fig. 1.30). Treatment of any underlying eczema in the canal, e.g. with 1% hydrocortisone cream, is important when the inflammation has settled.

Otorrhoea from middle ear disease

Chronic suppurative otitis media (tubotympanic disease)

Rupture of the tympanic membrane in acute otitis media produces a bloodstained, mucopurulent otorrhoea. The eardrum usually heals quickly, but if the inflammation persists and the eardrum skin fails to heal over the margins of the rupture, a persistent perforation will result. Persistent or recurrent mucoid discharge may then occur, especially if water enters the middle ear or in episodes of upper respiratory tract infections. Perforations as a result of recurrent acute otitis media usually occur in the pars tensa and do not involve the annulus. They are rarely associated with serious disease and are referred to as ‘safe’ perforations (Figs 1.31 and 1.32).

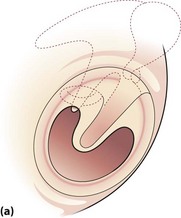

For those patients who have little trouble, a hearing aid to overcome hearing difficulties may be all that is required. Surgery is recommended for recurring discharge, for patients who are regular swimmers, and to produce a hearing improvement. The material for a graft is usually the patient’s own temporalis fascia, which is easily accessible (Fig. 1.33).

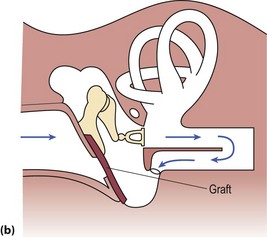

Chronic suppurative otitis media (atticoantral disease)

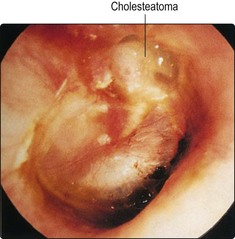

Long-standing Eustachian tube dysfunction may produce retractions and perforations of the tympanic membrane in the attic region, or may involve the annulus (Figs 1.34 and 1.35). These are associated with cholesteatoma (keratinizing epithelium in the middle ear). This is a destructive disease and can be life-threatening owing to the potential complications.

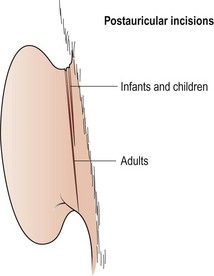

Because of the dangerous nature of this disease, surgery is invariably recommended. Excision of disease with preservation of hearing involves surgery on the mastoid and middle ear (mastoidectomy; p. 16). Usually the mastoid is exteriorized by removing the posterior ear canal wall to produce a cavity that can be inspected from the ear canal and cleaned as required. The drum defect may be grafted to minimize postoperative mucous discharge and optimize the hearing.

Discharging mastoid cavities

Many patients have either persistent or recurrent otorrhoea from surgically created mastoid cavities. There are many causes for this and most are amenable to treatment (Table 1.9). Uncontrolled infection of the middle ear or mastoid cavities may over many years predispose to carcinoma. This rare complication is heralded by a change in character of the otorrhoea from mucopurulent to bloody. It is invariably accompanied by the development of progressive otalgia and a facial paralysis.

Table 1.9 Causes and treatment of persistently discharging mastoid cavities

| Cause | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Small external opening | Enlarge meatus |

| Infection | Local toilet and topical antibiotic/steroid drops |

| Residual cholesteatoma | Revision mastoid surgery |

| Allergy to topical drops | Discontinue drops |

| High posterior canal wall | Surgery to lower canal wall |

| Neoplasia | Surgery ± radiotherapy |

Fracture of the temporal bone

A severe blow to the temporal or parietal region may result in a fracture of the temporal bone (p. 42). A conductive hearing loss is due to a combination of blood in the middle ear, ossicular disruption and tympanic membrane perforation. Sensorineural hearing loss will result if the fracture passes through the cochlea. Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhoea may occur but usually settles spontaneously. The patient should be prescribed systemic antibiotics.

Otorrhoea

Carefully examine an aural discharge; its appearance and odour may lead to a diagnosis.

Carefully examine an aural discharge; its appearance and odour may lead to a diagnosis.

The integrity of the eardrum must be assessed in patients with otorrhoea.

The integrity of the eardrum must be assessed in patients with otorrhoea.

Conservative treatment with local aural toilet and topical antibiotics is effective in tubotympanic chronic suppurative otitis media.

Conservative treatment with local aural toilet and topical antibiotics is effective in tubotympanic chronic suppurative otitis media.

Mastoid surgery will be required in cases of atticoantral chronic suppurative otitis media (cholesteatoma).

Mastoid surgery will be required in cases of atticoantral chronic suppurative otitis media (cholesteatoma).

Beware of a change in the character of a chronically discharging ear, particularly if accompanied by otalgia. It may herald development of neoplasia.

Beware of a change in the character of a chronically discharging ear, particularly if accompanied by otalgia. It may herald development of neoplasia.

Complications of middle ear infections

Ready access to medical treatment and the use of antibiotics has reduced the incidence of complications from acute otitis media. Mastoiditis is probably the most common complication and is more frequent in children. However, chronic ear disease is still responsible for cases of intracranial suppuration, which can be life threatening. It is useful to classify complications of middle ear disease into extracranial and intracranial (Table 1.10).

| Type | Complication |

|---|---|

| Extracranial | Acute mastoiditis |

| Facial paralysis | |

| Labyrinthitis | |

| Intracranial | Meningitis |

| Abscess | |

| – extradural | |

| – subdural | |

| – temporal | |

| – cerebellar | |

| Lateral sinus thrombosis |

Extracranial complications

Acute mastoiditis

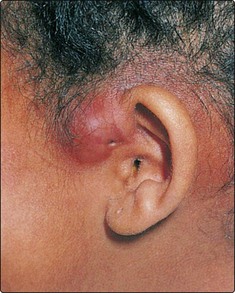

Mastoiditis is preceded by acute otitis media and is usually seen in young children. Inflammation of the mastoid lining produces severe pain, usually localized over the mastoid process. Perforation of the eardrum from otitis media may relieve the initial discomfort, but a gradual increase in pain with tachycardia and pyrexia suggests extension into the mastoid (Fig. 1.36). Early physical signs include a sagging or oedematous posterior ear canal wall, with oedema over the mastoid and zygomatic areas. Eventually the pinna is pushed down and out by a subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 1.37), and the drum head bulges or discharges pus.

In the early stages, administration of intravenous antibiotics may produce resolution of the inflammation. Prolonged treatment is necessary to ensure that resolution is complete and the hearing returns to normal. If there is any doubt about improvement, or if a subperiosteal abscess has developed, a cortical mastoidectomy is performed (Fig. 1.38).

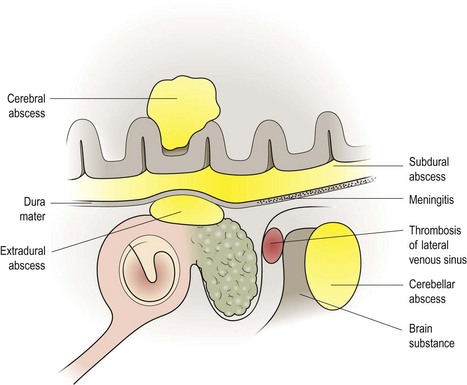

Intracranial complications

Intracranial abscess

The development of an intracranial abscess (Fig. 1.39) carries a significant mortality. An extradural abscess in the middle or posterior cranial fossa can occur by direct extension of middle ear infection. Erosion of the dural plate produces a dural reaction with granulation and abscess formation.

Temporal lobe abscess

A temporal lobe abscess may complicate acute or chronic middle ear disease (Fig. 1.40). The patient has a history of hearing loss and/or otorrhoea, and develops signs of cerebritis (headache, rigors, fever and vomiting). There may follow a latent period of up to several weeks, during which time the ear disease may appear to be controlled. The patient may then present with signs of raised intracranial pressure or focal signs of an abscess, e.g. a fit, paralysis or visual field changes. Patients with these signs require a CT or MRI scan. In all cases of cerebritis, high-dose parenteral antibiotics are required. Drainage of an established abscess is usually via a burr hole, and repeated aspiration of the cavity may be necessary.

Cerebellar abscess

A cerebellar abscess is uncommon, but can present with or after treatment for mastoiditis. Homolateral cerebellar signs of nystagmus, past pointing and ataxia, together with headache, demand an urgent CT scan (Fig. 1.41) and surgical drainage.

Thrombosis of the lateral venous sinus

Complications of middle ear infections

Acute mastoiditis is the most common complication of acute middle ear infection.

Acute mastoiditis is the most common complication of acute middle ear infection.

All patients with intracranial inflammation should have an otoscopic examination.

All patients with intracranial inflammation should have an otoscopic examination.

Intracranial complications can occur without otological symptoms.

Intracranial complications can occur without otological symptoms.

Treatment of intracranial complications takes precedence over therapy for underlying middle ear infection.

Treatment of intracranial complications takes precedence over therapy for underlying middle ear infection.

CT and MRI provide fast, accurate and non-invasive techniques for diagnosing intracranial complications.

CT and MRI provide fast, accurate and non-invasive techniques for diagnosing intracranial complications.

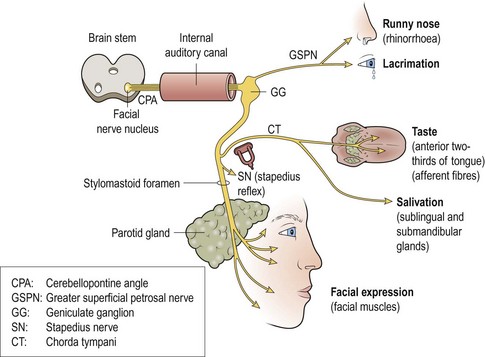

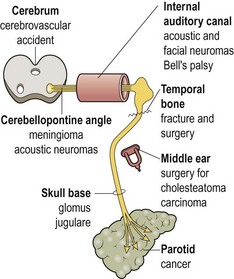

Facial palsy

The facial nerve has a complex course from the brainstem through the temporal bone and the parotid gland, before innervating the muscles of facial expression (Fig. 1.42). Running alongside this motor nerve are sensory fibres conveying taste from the anterior part of the tongue, and secretomotor fibres destined for the lacrimal, submandibular and sublingual glands.

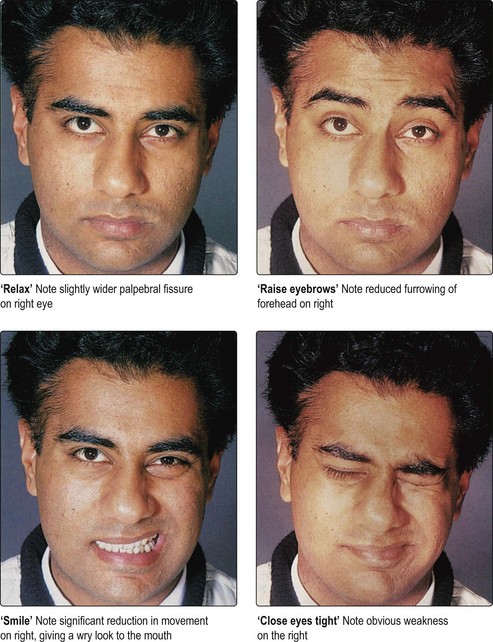

Damage to the facial nerve results in facial weakness and a considerable cosmetic deformity (Fig. 1.43). The neurological level of damage determines the clinical picture. In supranuclear lesions, e.g. stroke, the forehead is often spared due to bilateral innervation. Infranuclear lesions produce a lower motor neurone paralysis with both the upper and lower facial muscles involved.

Fig. 1.43 A patient with right-sided facial paralysis. Notice the cosmetic deformity on facial movement.

More severe lesions cause axon degeneration, and recovery occurs by regeneration. This may take from 3 to 12 months, and recovery is rarely complete. The most common causes of facial paralysis are shown in Table 1.11.

| Site | Aetiology |

|---|---|

| Intracranial | Acoustic neuroma |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA)* | |

| Brainstem tumour* | |

| Intratemporal | Bell’s palsy |

| Herpes zoster oticus | |

| Middle ear infection | |

| Trauma | |

| – surgical | |

| – temporal bone fracture | |

| Extratemporal | Parotid tumours |

| Miscellaneous | Sarcoidosis, polyneuritis |

Clinical history

A detailed history may reveal the likely aetiology of a facial paralysis and also its site. For example, Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome; Fig. 1.44) are frequently heralded by otalgia before the onset of facial weakness. A chronically discharging ear complicated by facial nerve deficits is invariably due to the atticoantral (cholesteatoma) type of chronic suppurative otitis media. Facial paralysis resulting from surgical trauma (particularly in otological procedures) and temporal bone fractures is easily diagnosed. Tissue masses in the region of the parotid, with associated facial paralysis, indicate malignancy. However, the sinister adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid may present with an isolated cosmetic facial defect and no obvious palpable neck mass.

Clinical examination

It is important to establish whether the facial paralysis is supranuclear (forehead spared) or infranuclear (Fig. 1.45). Most patients fear a stroke as the cause, and this can be excluded rapidly if the frontalis muscle is paretic. The facial movements should be assessed in the forehead, around the eyes, the cheek and mouth. Otoscopic examination may reveal the vesicles of herpes zoster oticus, or the presence of cholesteatoma in a chronically discharging ear. Rarely, a glomus jugulare tumour may be visible. A parotid tumour may be palpable in the neck, but examination of the oropharynx is essential to exclude a lesion of the deep lobe of the parotid, pushing the tonsil medially. A complete examination of the cranial nerve should be made. Further investigations may include hearing tests, particularly if otoscopy was normal.

Management

Specific causes of facial palsy

Trauma

Facial palsy

Many patients equate facial palsy with having suffered a stroke.

Many patients equate facial palsy with having suffered a stroke.

If the forehead is involved, the palsy is due to an infranuclear (lower motor neurone) lesion and reassurance can be given that a CVA has not occurred.

If the forehead is involved, the palsy is due to an infranuclear (lower motor neurone) lesion and reassurance can be given that a CVA has not occurred.

Always perform otoscopy in cases of facial palsy, as it may reveal the few treatable causes of facial paralysis.

Always perform otoscopy in cases of facial palsy, as it may reveal the few treatable causes of facial paralysis.

Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. All patients with Bell’s should receive oral steroids early on.

Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. All patients with Bell’s should receive oral steroids early on.

A Bell’s palsy which is complete or which shows no evidence of recovery within 6 weeks requires referral to an ENT surgeon.

A Bell’s palsy which is complete or which shows no evidence of recovery within 6 weeks requires referral to an ENT surgeon.

Parotid neoplasia may present as a facial palsy.

Parotid neoplasia may present as a facial palsy.

Patients undergoing mastoid surgery should be counselled on the risks of facial nerve damage.

Patients undergoing mastoid surgery should be counselled on the risks of facial nerve damage.

The major complications of a facial palsy are related to the eye and to self-image.

The major complications of a facial palsy are related to the eye and to self-image.

Disorders of balance – introduction and otological causes

Imbalance, dizziness or ‘vertigo’ can all be symptoms of an underlying disturbance of the vestibular system (p. 2). The pathology may be peripheral (otological) or central (brainstem), producing a hallucination of movement (vertigo). There are many inputs into the vestibular system – eyes, ears, joint proprioception, signals from the cerebellum (Fig. 1.46). Each of these inputs may influence balance, as will primary disorders of the labyrinths and their central connections.

Symptoms

History taking is the key to diagnosing balance disorders. It is important to characterize the main symptom. Patients tend to use the term ‘dizzy’ to describe a variety of different symptoms. In general, the symptoms may be classified as in Table 1.12.

| Term | Symptom | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Vertigo | An illusion of rotary movement, worse in the dark | Peripheral vestibular disease, rarely central vestibular pathology |

| Lightheadedness | A feeling of fainting | Cardiovascular (postural hypotension, antihypertensives), ototoxic drugs Psychiatric conditions |

| Unsteadiness | Difficulty with gait, a tendency to fall or veer to one side | Ageing process with general incoordination, rarely neurological |

| Loss of consciousness, blackouts | Usually a clear-cut history | Neurological (epilepsy), cardiac arrhythmias |

It is important to question the patient on the following points:

the first attack – mode of onset and duration

the first attack – mode of onset and duration

changes in hearing and the presence of tinnitus

changes in hearing and the presence of tinnitus

relation to activity (head movements, body posture, turning in bed)

relation to activity (head movements, body posture, turning in bed)

effect of darkness or closing the eyes

effect of darkness or closing the eyes

concomitant cardiovascular disease

concomitant cardiovascular disease

The duration of symptoms is important to ascertain, as this is a guide to the potential aetiology (Table 1.13).

Table 1.13 Duration of symptoms of imbalance in relation to aetiology

| Duration | Aetiology |

|---|---|

| Seconds | Cervical spondylosis |

| Postural hypotension | |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | |

| Minutes to hours | Ménière’s disease |

| Labyrinthitis | |

| Hours to days | Acute labyrinthine failure (without compensation) |

| Ototoxicity | |

| Central vestibular disease |

Signs

The tympanic membranes should be examined for evidence of middle ear disease. The eyes are tested for nystagmus (p. 5), which is classified according to the quick phase of the movement.

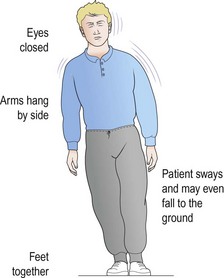

All the cranial nerve and cerebellar functions are formally assessed. The patient is requested to stand to perform Romberg’s test (Fig. 1.47). An abnormality of gait may be unmasked when the subject walks across the room and turns round. A positional test is mandatory, as are lying and standing blood pressure readings.

Otological causes of imbalance

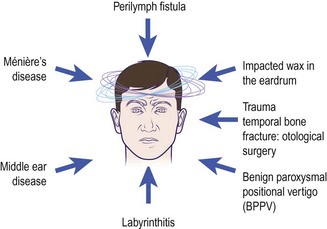

Figure 1.48 shows the common otological diseases producing vertigo.

Middle ear disease

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) often causes children to become unsteady on their feet. If surgery is required, myringotomy, aspiration of fluid and grommet insertion restore stability.

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) often causes children to become unsteady on their feet. If surgery is required, myringotomy, aspiration of fluid and grommet insertion restore stability.

Acute otitis media may produce various symptoms of imbalance, including true vertigo. Treatment is bed rest, antibiotics, analgesics and vestibular sedatives.

Acute otitis media may produce various symptoms of imbalance, including true vertigo. Treatment is bed rest, antibiotics, analgesics and vestibular sedatives.

Chronic suppurative otitis media (atticoantral disease). Erosive cholesteatoma may invade the labyrinth, producing a fistula connecting the middle and inner ear, which may give a positive fistula sign (p. 5). Patients with a discharging ear and vertigo should be seen urgently by an ENT surgeon.

Chronic suppurative otitis media (atticoantral disease). Erosive cholesteatoma may invade the labyrinth, producing a fistula connecting the middle and inner ear, which may give a positive fistula sign (p. 5). Patients with a discharging ear and vertigo should be seen urgently by an ENT surgeon.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

This is an episodic vertigo, usually dramatically described as occurring on turning the head. It can follow an upper respiratory tract infection or head injury. The vertigo lasts for several seconds and fatigues with repetitive stimulation such as repeated positional testing (p. 5). Most cases settle spontaneously or with specific physiotherapy manoeuvres. Vestibular sedatives have no therapeutic advantage.

Ménière’s disease (endolymphatic hydrops)

Ménière’s disease typically affects young to middle-aged adults. The cardinal features are shown in Table 1.14. Attacks tend to occur in clusters. Distortion of hearing is very characteristic. Acute attacks are very distressing and can lead to chronic unsteadiness.

| Symptom (episodic attacks) | Descriptive details |

|---|---|

| Vertigo | The patient is normal between attacks |

| Hearing loss | Unilateral or bilateral, but level fluctuates |

| Tinnitus | Usually precedes an attack of vertigo |

| Aural fullness | Described as a pressure, fullness or warm feeling in the ear |

Other otological causes

Disorders of balance – introduction and otological causes

Ascertain the precise nature of the imbalance.

Ascertain the precise nature of the imbalance.

The duration of symptoms gives vital clues to the aetiology.

The duration of symptoms gives vital clues to the aetiology.

All patients with vertigo should have an otoscopic examination to exclude middle ear pathology.

All patients with vertigo should have an otoscopic examination to exclude middle ear pathology.

All patients should have their hearing assessed to exclude a unilateral deficit and the presence of an acoustic neuroma.

All patients should have their hearing assessed to exclude a unilateral deficit and the presence of an acoustic neuroma.

Otological causes of imbalance improve with time due to central compensation if the brain is normal.

Otological causes of imbalance improve with time due to central compensation if the brain is normal.

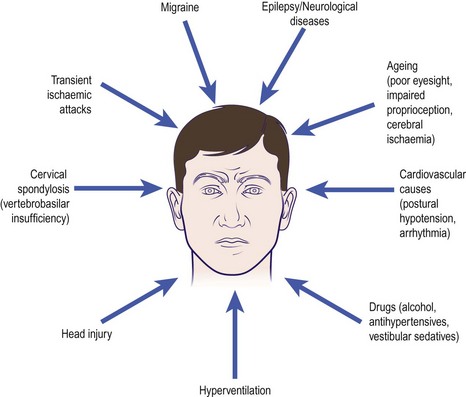

Disorders of balance – non-otological causes

Non-otological diseases producing imbalance are summarized in Figure 1.49. True vertigo – illusion of rotary movement – is not a feature of non-otological imbalance (Fig. 1.49). Instead, these aetiologies tend to produce lightheadedness or unsteadiness (see Table 1.12, p. 20). Many patients will have evidence of associated cardiovascular and neurological symptoms and signs.

Ageing

Some degree of imbalance is invariable with the ageing process. The cause is multifactorial, with many of the pathologies shown in Figure 1.49 presenting simultaneously.

Migraine

Although this disease is characterized by a severe hemicranial headache (p. 53), the patient commonly has a feeling of unsteadiness and imbalance. A thorough clinical history will clinch the diagnosis. It is associated with Ménière’s disease.

Tinnitus

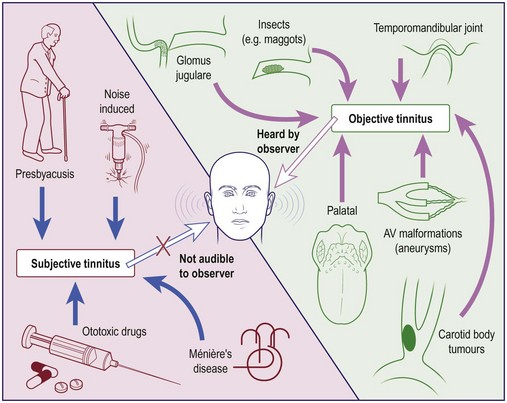

Noises in the ear, real or imagined, are called tinnitus. This condition affects about 10% of the UK population and is most common in patients who have been exposed to long-term, high-intensity noise. The temporomandibular joint, Eustachian tube and carotid artery can all produce sounds which are usually innocent and classified as objective forms of tinnitus, referred to as somatosounds (Fig. 1.50).

Aetiology and clinical presentation

Subjective causes of tinnitus (heard only by the patient) are extremely common and the majority of them are treated conservatively (Fig. 1.50). Otoscopy and audiology will identify the majority of middle ear conditions causing tinnitus (Table 1.15), which when corrected may improve the symptoms. Very few tinnitus sufferers need detailed investigation. However, unilateral symptoms, particularly if accompanied by hearing loss, should have a full neuro-otological assessment, including an MRI scan.

Table 1.15 Ear diseases known to be associated with subjective tinnitus

| Location | Disease |

|---|---|

| External ear | Wax |

| Middle ear | Otosclerosis |

| Middle ear effusion | |

| Inner ear | Noise-induced hearing loss |

| Presbyacusis | |

| Ménière’s disease | |

| Trauma (surgery, head injury) | |

| Ototoxic drugs | |

| Labyrinthitis | |

| Acoustic neuroma |

The most common form of subjective tinnitus is a rushing, hissing or buzzing noise; it is frequently associated with sensorineural hearing loss. The patient may be unaware of the hearing loss, especially if it is a high-frequency deficit of moderate severity. The character of the tinnitus may give a clue to the aetiology (Table 1.16).

Table 1.16 The quality of tinnitus and its likely site of origin

| Quality of tinnitus | Site of pathology |

|---|---|

| High pitched, hissing or rushing | Inner ear, brainstem, auditory cortex |

| Banging, crackling, popping | Middle ear |

| Pulsatile | Normal carotid artery, vascular tumour |

Presbyacusis (p. 9) is a common cause of tinnitus. Owing to the gradual onset, the patient may be unaware of the noise until a heavy cold produces a temporary conductive hearing loss, highlighting the tinnitus.

Management

Tinnitus

Many tinnitus sufferers are managed by simple reassurance.

Many tinnitus sufferers are managed by simple reassurance.

Unilateral tinnitus, particularly if associated with a hearing deficit, should be fully investigated.

Unilateral tinnitus, particularly if associated with a hearing deficit, should be fully investigated.

Tinnitus associated with sensorineural hearing loss is best treated with a hearing aid.

Tinnitus associated with sensorineural hearing loss is best treated with a hearing aid.

Tinnitus maskers provide effective control for 30% of sufferers.

Tinnitus maskers provide effective control for 30% of sufferers.

Objective causes of tinnitus are rare. The most common is transmitted noise from the carotid artery.

Objective causes of tinnitus are rare. The most common is transmitted noise from the carotid artery.

The auricle (pinna) and ear wax

The auricle (pinna)

Congenital abnormalities

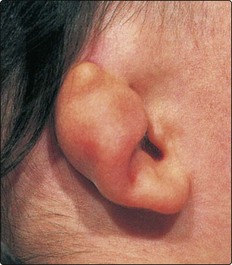

The auricle develops from six separate hillocks on the side of the embryo’s head. Minor congenital abnormalities are not uncommon, and most do not require treatment (Fig. 1.51). Major abnormalities include a complete absence of the pinna (anotia) or severe deformities (Fig. 1.52). Severe malformations of the pinna and ear canal are not always associated with abnormalities of the middle or inner ear, as these two elements have separate embryological origins. Indeed, many children may have a conductive hearing loss but normal inner ear function.

The results of surgical correction of these auricular defects have been generally unsatisfactory. The recent development of titanium implants, however, allows excellent cosmetic prostheses to be anchored to the mastoid (Fig. 1.53). As well as providing an anchor, the titanium parts can act as the transmitter for a bone conduction hearing aid (p. 11).

Bat ears

Bat ears are the most common abnormalities of the auricle and are usually bilateral (Fig. 1.54). Prominent ears may be moulded at birth (within 24 hours), as the cartilage has not formed its ‘memory’ for shape. Surgical correction, however, is best left until about 6–7 years and is mainly designed to recreate an antihelical fold.

Preauricular sinus

The preauricular sinus is an embryological remnant which appears as a small pit anterior to the helical root. No intervention is required unless the sinus becomes infected (Fig. 1.55). Treatment involves complete excision of the sinus tract to avoid recurrence.

Infections and other conditions

Dermatitis from nickel jewellery or eardrops is usually localized to the lobule or concha, respectively. Resolution is rapid if the sensitizing agent is removed. Eczematous and psoriatic eruptions of the auricular skin are not uncommon and will require application of topical creams and ointments (Fig. 1.56).

Ear wax

Ear wax contains sebaceous material and the products of the ceruminous glands which line the outer one-third of the ear canal. These secretions combine with desquamated skin and hair to form wax, about which many patients develop an obsession. Wax (cerumen) varies in colour and consistency, and its production appears to be partly controlled by circulating catecholamines. It is normal to have some cerumen in the ear canal. Wax provides protection to the skin and also possesses bactericidal activity. Ear canal epithelium migrates outwards, providing a natural cleaning mechanism for desquamated tissue and cerumen. Attempts to clean the ear by a patient invariably force the ear canal contents deeper into the meatus (Fig. 1.57). Wax impaction therefore is a common cause of hearing loss. If water enters the ear, the desquamated keratin expands, often trapping fluid in the deep meatus. This may cause an otitis externa unless the plug is removed.

Removal of wax

Meatal occlusion, impaction, irritation, hearing loss or otitis externa and clinical inspection of the eardrum are all indications for removing wax. The simplest method is to syringe the ear. Tap water at body temperature is used. The pinna is lifted to straighten the ear canal and the water jet aimed at the roof of the canal, never directly at the eardrum. The canal and drum head must be examined afterwards. Patients who have perforations should not have their ears syringed (Table 1.17). Curetting wax from the canal requires a good light and a cerumen scoop or hoop. In difficult or refractory cases a microscope and sucker may be used in outpatients, or under general anaesthesia. Hard impacted wax may need to be softened with topical ceruminolytic ear drops before removal (p. 28).

‘Attic’ wax (attic crust)

Chronic suppurative otitis media (atticoantral) with cholesteatoma in the attic can appear on inspection to resemble wax above the malleus handle. This is referred to as ‘attic’ wax (Fig. 1.58). Removal is usually painful and may induce vertigo. The true nature of the problem is revealed once the cholesteatoma is visualized deep to the wax crust.

The auricle (pinna) and ear wax

Malformations of the pinna and ear canal are not always associated with abnormalities in the middle and inner ear.

Malformations of the pinna and ear canal are not always associated with abnormalities in the middle and inner ear.

Perichondritis requires aggressive treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, astringents and analgesics to prevent suppuration and cartilage necrosis.

Perichondritis requires aggressive treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, astringents and analgesics to prevent suppuration and cartilage necrosis.

Wax in the ear canal is normal.

Wax in the ear canal is normal.

Discourage the use of cotton buds to clear wax debris.

Discourage the use of cotton buds to clear wax debris.

Remove soft wax by syringing; hard wax will require prior softening.

Remove soft wax by syringing; hard wax will require prior softening.

Do not syringe the ear in the presence of a perforated eardrum.

Do not syringe the ear in the presence of a perforated eardrum.

Beware of the ‘attic wax crust’: it may conceal an underlying cholesteatoma associated with chronic suppurative otitis media.

Beware of the ‘attic wax crust’: it may conceal an underlying cholesteatoma associated with chronic suppurative otitis media.

Otological trauma and foreign bodies

Injuries to the pinna

Auricular haematoma

Blunt trauma to the ear may produce a haematoma. Bleeding occurs deep to the perichondrium, which is stripped from the underlying cartilage so that the ear becomes swollen and the normal architecture of the folds is lost (Fig. 1.59). As the cartilage depends on the perichondrium for survival, necrosis and subsequent scar formation will produce the typical ‘cauliflower ear’.

Injuries to the middle and inner ear

Otitic barotrauma

Otitic barotrauma can produce otalgia with some extravasation of blood into the middle ear so that a haemotympanum occurs (Fig. 1.60). In severe cases the eardrum may rupture. The aetiology is an inability to ventilate the middle ear due to abnormal function of the Eustachian tube. The condition is particularly seen when the ambient pressure is rising, e.g. descent in flight or scuba diving. Treatment comprises a repeated Valsalva manoeuvre to open up the Eustachian tube, in addition to topical nasal decongestants. Myringotomy may be needed in some cases. Patients who fly and suffer regularly are instructed to use prophylactic measures to prevent Eustachian tube problems (e.g. topical nasal decongestants and repeated swallows). Occasionally insertion of a ventilation tube overcomes the problem.

Head injuries

Head injuries may be associated with temporal bone fractures (p. 42). These cause hearing loss, which may be sensorineural if the fracture line passes through the cochlea. In such cases vertigo and facial paralysis may also be present. However, otological trauma can occur in head injuries without the presence of a fracture. The cochlea can be concussed and produce a hearing loss. Labyrinthine damage may lead to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo or a vague feeling of imbalance. Lesions of the central vestibular apparatus can lead to long-term symptoms if compensation is not complete.

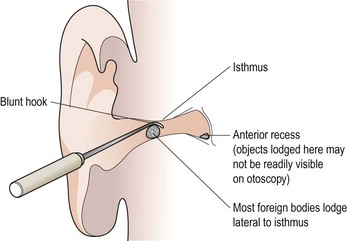

Foreign bodies

Most foreign bodies will either lodge lateral to the isthmus (the narrowest part of the ear canal) or impact at that site (Fig. 1.61). However, if located in the deep meatus they may reside in the anterior recess and therefore not be seen on routine otoscopy. Always check both ears and the nose for foreign bodies in children.

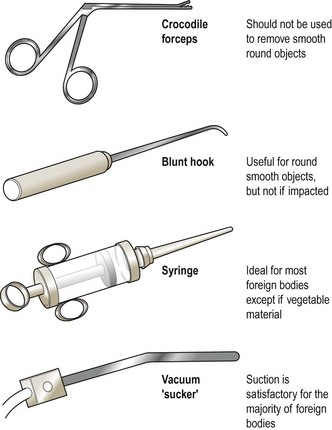

The method of removal depends on the type of foreign body (Figs 1.62 and 1.63) and its location. A pair of crocodile forceps can easily grasp objects such as cotton wool, paper and pieces of foam sponge. Forceps should not be employed to grasp smooth round objects as they are likely to spring out of the jaws and end up deeper in the meatus. A blunt hook may be inserted around the object, particularly if round, and gently teased out (Fig. 1.61). Suction apparatus is also a useful tool in certain cases, e.g. cosmetic beads.

Otological trauma and foreign bodies

An auricular haematoma or suspected perichondritis requires urgent treatment to avoid a long-term cosmetic defect.

An auricular haematoma or suspected perichondritis requires urgent treatment to avoid a long-term cosmetic defect.

Head injuries without a fracture can produce severe cochleovestibular symptoms.

Head injuries without a fracture can produce severe cochleovestibular symptoms.

Avoid medical litigation by preoperatively informing patients undergoing ear operations of potential risks to the hearing, balance and facial movement.

Avoid medical litigation by preoperatively informing patients undergoing ear operations of potential risks to the hearing, balance and facial movement.

Most foreign bodies lodged in the ear canal are asymptomatic.

Most foreign bodies lodged in the ear canal are asymptomatic.

Attempt removal only if you have the skills and instruments.

Attempt removal only if you have the skills and instruments.

It is frequently safer to remove foreign bodies in children under general anaesthesia.

It is frequently safer to remove foreign bodies in children under general anaesthesia.

Do not use forceps to extract smooth round objects.

Do not use forceps to extract smooth round objects.

Do not syringe out vegetable foreign bodies as they will swell and impact in the ear canal.

Do not syringe out vegetable foreign bodies as they will swell and impact in the ear canal.

Aural drops

There are numerous preparations of aural drops (Table 1.18).

Table 1.18 Topical aural preparations

Instillation of aural drops

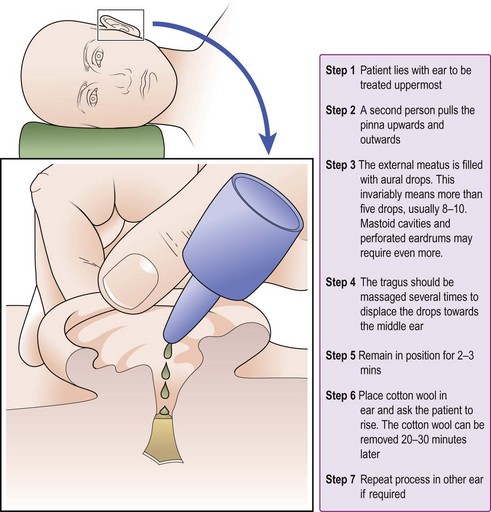

The maximum benefit of aural drops can only be gained if they are correctly instilled (Fig. 1.64). If possible, any canal debris should be cleaned before their use; this is particularly important in cases of otitis externa.

Aural drops

Simple wax softeners are the most effective, i.e. warm olive oil or sodium bicarbonate.

Simple wax softeners are the most effective, i.e. warm olive oil or sodium bicarbonate.

Long-term use of topical antibacterial drops can predispose to fungal infection and contact dermatitis.

Long-term use of topical antibacterial drops can predispose to fungal infection and contact dermatitis.

Aural drops are only effective if correctly applied. Give the patient precise instructions on the procedure for instillation.

Aural drops are only effective if correctly applied. Give the patient precise instructions on the procedure for instillation.