Chapter 7 The digestive system

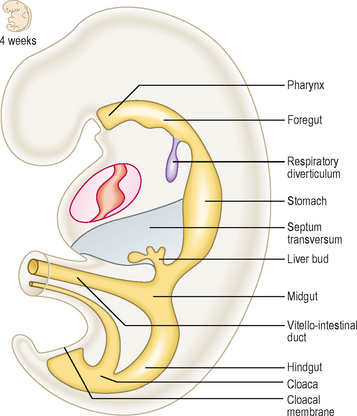

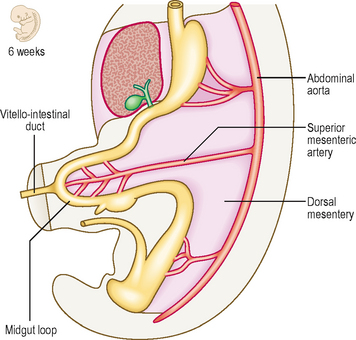

The longitudinal and lateral folding (see Chapter 1) of the embryo results in the incorporation of part of the yolk sac. Thus, the endoderm germ layer is incorporated into the embryo and forms the primitive gut tube (Fig. 7.1). In the anterior part of the embryo the incorporation of the endoderm into the head fold results in the formation of the foregut, whilst in the posterior part of the embryo the hindgut forms. The foregut is divided into a cranial and a caudal portion. The cranial portion develops within the head and neck, as the pharynx. This is particularly associated with the pharyngeal arches which are lined by endoderm. In the middle region the midgut forms and initially this is in direct continuity with the remaining yolk sac. The persisting connection becomes the vitello-intestinal (or vitelline) duct. Each region of the embryonic gut tube is supplied by its specific artery: the coeliac, superior mesenteric and inferior mesenteric arteries for the foregut, midgut and hindgut respectively. In addition to the primitive gut tube, the endoderm layer also gives rise to the parenchyma of the two large glandular organs associated with the gastrointestinal duct, the liver and the pancreas. The connective tissue, smooth muscle and serosal layer of the gut tube and the connective tissue of the pancreas arise from the splanchnopleuric lateral plate mesoderm (see Chapter 1).

Primitive gut tube

Mesenteries

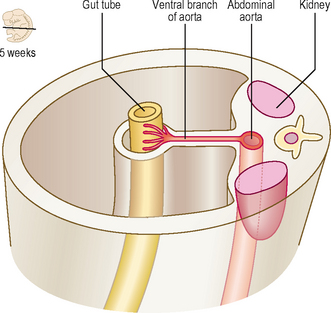

As the gut tube is incorporated into the body of the embryo it comes to be suspended by a dorsal mesentery (Fig. 7.3). This is formed from the serosal membrane derived from the lateral plate splanchnopleuric mesoderm. As the gut tube is incorporated into the body of the embryo, ‘wings’ of amnion push in laterally (responsible for the lateral folding), and these squeeze the connection of the yolk sac and the gut tube. Eventually the endodermal gut tube is formed and it moves ventrally, leaving the overlying splanchnopleuric mesoderm still in contact with the posterior wall of the embryo. This suspensory structure is called the dorsal mesentery of the gut tube and extends from the lower part of the oesophagus to the cloacal part of the hindgut. It has two adjacent layers of serosal membrane. The two layers diverge on each side, forming the mesentery, which is reflected onto the dorsal wall of the embryo. Since the mesentery is related to the posterior wall of the embryo, close to where the dorsal aorta lies, there is the opportunity for ventral arterial branches of the abdominal aorta to lie between the two layers of the mesentery to gain access to the gut tube without piercing the future peritoneal membrane (Fig. 7.2). In the situation where the gut tube is invested by splanchnopleuric mesoderm all around, aside from the point at which the mesentery begins its investment, the gut tube is said to be intraperitoneal. If an organ is not suspended by a mesentery, thus outside of the peritoneum and in contact with the posterior abdominal wall, it is said to be retroperitoneal, e.g. kidney, parts of the duodenum, pancreas (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2 A transverse section through the embryo showing the peritoneal and retroperitoneal structures.

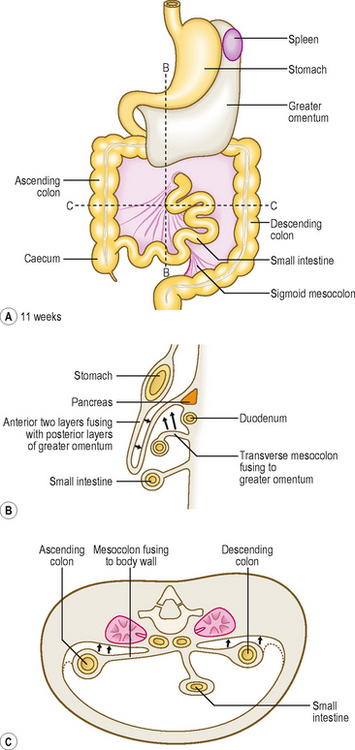

With further development the dorsal mesentery is lost for some parts of the adult derivatives of the gut tube: duodenum and the ascending and descending colon. In this situation those parts of the tube are more firmly anchored to the underlying connective tissues. The dorsal mesentery related to the stomach is known as the dorsal mesogastrium, and elongates considerably, as the greater omentum.

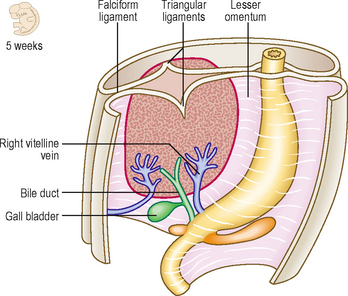

For the caudal part of the foregut another mesentery develops, the ventral mesentery. The ventral mesogastrium is derived from the septum transversum, and there is, therefore, a ventral mesentery only for the portion of the gut tube adjacent to the septum transversum. Thus, the terminal part of the oesophagus, the stomach and the initial portion of the duodenum are invested by a ventral mesentery (Fig. 7.3). The liver develops within the ventral mesentery and divides the ventral mesogastrium into two parts. The mesentery lying between the stomach and the liver is the lesser omentum. The part of the mesentery lying between the liver and the ventral wall of the embryo is the falciform ligament. In all these cases the mesenteries are double layers, thus allowing for the possibility of other structures such as blood vessels and nerves to occupy those spaces between the two layers.

Foregut

The cranial (pharyngeal) portion of the foregut, and its subsequent development is described in Chapter 11. The remainder of the foregut is termed the caudal foregut.

Development of oesophagus

The initial component of the caudal foregut is the oesophagus. Initially, it too has a dorsal mesentery, which disappears, bringing the oesophagus into its adult position in the posterior mediastinum. As described in Chapter 5 the endodermal respiratory diverticulum arises as a ventral bud off the future oesophagus. Because of the growth of the thoracic organs the oesophagus is lengthened.

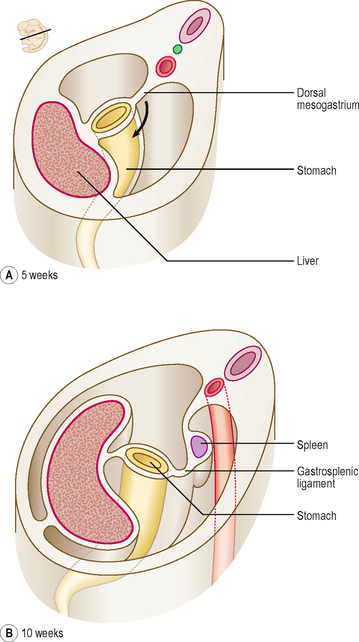

Development of stomach

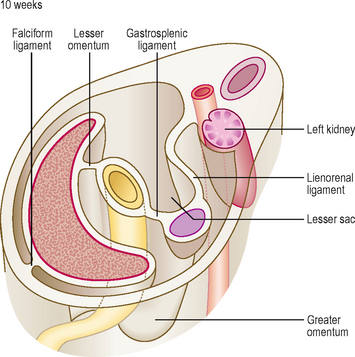

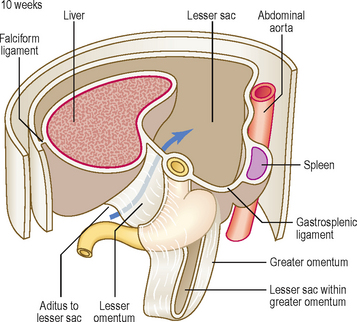

At first the stomach is merely a cylindrical tube, like the rest of the gut tube, passing craniocaudally, and it is invested by the dorsal and ventral mesenteries (Fig. 7.4A). Conventionally, the developing stomach is initially described as being fusiform or flask-shaped. The stomach undergoes a clockwise rotation through about 90° (Fig. 7.4B). The uneven growth is evident by the shorter lesser curvature and the longer greater curvature of the stomach; this is because the original posterior wall grows quicker than the anterior wall. This rotation of the stomach also results in the dorsal mesogastrium being pulled over to the left side (Fig. 7.5). Consequently, the small compartment lying between the stomach and the dorsal wall of the embryo develops as the lesser sac of the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 7.5). Developing within the dorsal mesogastrium is the spleen, and this is thus carried over to the left side so that it comes to occupy the left hypochondrium of the abdominal cavity in the adult. The portion of the dorsal mesogastrium that lies between the stomach and spleen becomes the gastrosplenic ligament, whilst the part lying between the spleen and the dorsal wall of the embryo becomes the lienorenal ligament (Fig. 7.5).

As the liver develops in the ventral mesogastrium and enlarges it is carried towards the right. This accentuates the separate compartmentalization of the lesser sac. The ventral mesogastrium of the foregut is carried rightwards with the liver. The border of the mesogastrium between the liver and the ventral wall of the embryo becomes the falciform ligament. The portion between the stomach and liver becomes the lesser omentum. There is a free border of the lesser omentum (that contains the hepatic artery, bile duct and hepatic portal vein) lying between the duodenum and the visceral surface of the liver (Fig. 7.6).

The lesser sac communicates with the greater sac of the peritoneal cavity (the main part) via the aditus to the lesser sac. The lesser sac itself is limited in its extent by the greater omentum, the latter sealing off each of its lateral borders. In the fetus this means the lesser sac reaches as far as the inferior border of the greater omentum, though the two double layers of the latter gradually fuse, thus limiting the inferior extent of the lesser sac in the adult to a point just beyond the future greater curvature of the stomach (Fig. 7.6).

Development of duodenum

The duodenum arises from two adjacent regions of the gut tube: the foregut and the midgut. The junction between these two regions lies at the mid-point of the duodenum, at the level of the entry of the bile duct (Fig. 7.7). Whereas initially the lumen of the duodenum is hollow, by the second month proliferation of its cellular lining results in a solid duodenum. A process of recanalization soon follows so that the hollow lumen is restored. If this process fails then a stenosis of the duodenum results which would cause an intestinal obstruction, and the infant would fail to thrive. As the stomach rotates clockwise the duodenum also rotates to the right, and because of its position comes to lie on the future posterior abdominal wall. This rotation is assisted by the development of the pancreas, which lies within the mesoduodenum. As well as the rotation of the duodenum this region of the gut also becomes C-shaped resulting from the changes to the stomach, as well as differential growth of the duodenum itself. Because the duodenum arises from both foregut and midgut it has dual arterial blood supplies: branches from the coeliac artery (the artery of the foregut) and branches from the superior mesenteric artery (the artery of the midgut), with corresponding venous drainage to the hepatic portal vein. The stomach is invested on both its anterior and posterior surfaces by peritoneum. The mesoduodenum is lost with further development. Thus, the mesoduodenum is ‘plastered’ against the abdominal wall, and its posterior layer fuses with the adjacent parietal layer of the abdominal wall. Consequently, the duodenum is covered by peritoneum only on its anterior surface, and this is parietal peritoneum; thus the duodenum is retroperitoneal. This position of the duodenum seals off the lower extent of the aditus to the lesser sac.

Other foregut derivatives

Pancreas

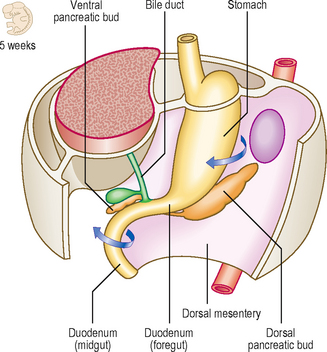

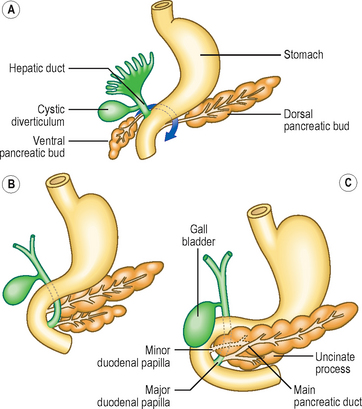

The parenchyma of the pancreas develops from the endodermal lining of the duodenum. Dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds arise from the duodenum close to the origin of the hepatic bud (see later) from about 4 weeks (Fig. 7.8A). The dorsal bud lies in the dorsal mesentery slightly higher that the ventral bud which lies in the ventral mesentery. However, as the duodenum rotates rightwards the ventral bud moves dorsally. The dorsal bud rotates around the duodenum, coming to lie just inferior to the ventral bud (Fig. 7.8B). Thus, the two buds are in contact, both in the same plane, but they enclose the superior mesenteric blood vessels. It therefore appears as though the vessels emerge from within the substance of the pancreas. The two embryological parts of the gland fuse, even though initially the duct systems open separately into the duodenum. Soon, the duct systems fuse too. The duct of the larger dorsal bud becomes the main pancreatic duct, with the duct of the smaller ventral bud merging with that of the dorsal bud. This duct arrangement enters the duodenum at the major duodenal papilla in its medial wall (Fig. 7.8C).

Development of liver and biliary tract

The hepatic diverticulum arises from the endodermal lining of the foregut just slightly cranial to the opening of the pancreatic duct at about the middle of the third week. This bud of tissue pushes into the septum transversum (see Chapter 3). As this bud enlarges, the connection it has with the duodenum narrows, thus forming the bile duct (Fig. 7.9). The gall bladder develops as a small ventral outpouching, with the connection to the bile duct persisting as the cystic duct. Gall bladder ducts become solid during their early development, but later recanalize. Failure of recanalization results in extrahepatic biliary atresia. If this is not correctable surgically, a liver transplant is needed. The hepatic diverticulum enlarges to fill almost all of the septum transversum. The margins of the septum that remain become the peritoneal ligaments that join the liver to surrounding structures, being parts of the ventral mesogastrium. The falciform ligament is reflected from the liver to the ventral wall of the embryo; the triangular and coronary ligaments reflect onto the undersurface of the future diaphragm; and the lesser omentum reflects onto the lesser curvature of the stomach (Fig. 7.9). The future peritoneum covers most of the surface of the liver, with the exception of the bare area, where the organ lies in contact with the diaphragm. The Kupffer cells are bone marrow-derived and invade the liver to line the sinusoids. By the tenth week of development the liver begins to form blood cells, which accounts for the relatively large size of the liver at this stage.

Midgut

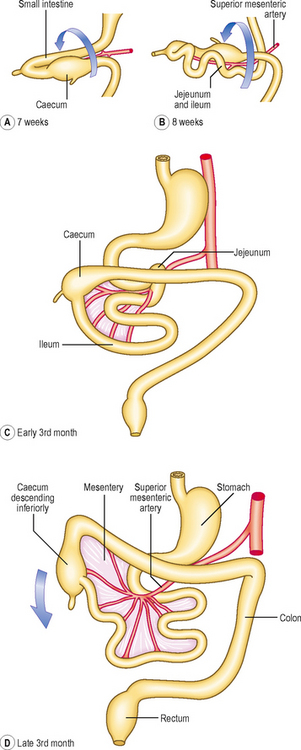

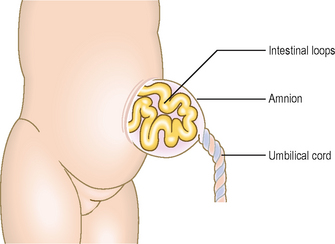

Initially, the midgut communicates with the yolk sac via a wide communication, which narrows to become the vitello–intestinal duct. The midgut begins at the mid-point of the duodenum, terminating approximately two-thirds of the way along the length of the transverse colon. The artery of the midgut is the superior mesenteric artery, which reaches the gut lying between the two layers of dorsal mesentery. The midgut tube rapidly elongates, which poses a problem in that the peritoneal cavity in which it is contained is too small. As a consequence the midgut herniates out of the abdominal cavity into the umbilical cord at the end of the sixth week (Fig. 7.10). This is the physiological umbilical hernia. As the gut tube enters the umbilical cord it rotates anticlockwise approximately 90° (Fig. 7.11A). On return of this loop the tube rotates a further 180° anticlockwise (Fig. 7.11B, C). These rotations take place about the axis of the vitello-intestinal duct–superior mesenteric artery. The increase in space in the abdominal cavity as the embryo grows is thought to account for the reduction of the physiological umbilical hernia. The midgut forms the second half of the duodenum, the jejunum, ileum, ascending colon and two-thirds of the transverse colon. With the rotation of the midgut on return from the hernia, the caecum is carried from its original position under the liver to its adult location in the right iliac fossa (Figs 7.11D and 7.12A). Occasionally, the caecum remains located under the liver (a subhepatic caecum). The vermiform appendix arises at the apex of the caecum.

Most of the midgut retains the original dorsal mesentery, though parts of the duodenum derived from the midgut do not. The mesentery associated with the ascending colon and descending colon is reabsorbed, bringing these parts of the colon into close contact with the body wall (Fig. 7.12C). The transverse colon retains its dorsal mesentery as the transverse mesocolon, but the latter fuses with the anterior two layers of the greater omentum, thus accounting for the observation that the transverse colon is adherent to the posterior surface of the greater omentum (Fig. 7.12B).

Abnormal physiological herniation of the midgut may be associated with defective body wall closure. There are two main types: omphalocele (Fig. 7.13) and gastroschisis. In an omphalocele the abdominal viscera herniate through the abdominal wall in the region of the umbilicus, to lie outside the body, though covered with a layer of the amnion. This arises because of incorrect return of the physiological umbilical hernia. In gastroschisis there is a direct herniation of abdominal contents through the abdominal wall into the amniotic sac. In cases of gastroschisis the abnormalities may be correctable, though often with omphalocele there are other additional abnormalities (often involving the heart) so affected infants are less likely to survive.

The vitello-intestinal duct is normally obliterated but in a small percentage of people it persists as Meckel’s diverticulum. This pouch is normally located approximately halfway along the length of the midgut in the small intestine. It is significant because it may contain pancreatic or gastric mucosa and the secretions from these tissues can erode the mucosa, causing pain, which in its early phase may mimic that of appendicitis. Occasionally, the vitello-intestinal duct can persist, forming fibrous strands, so-called vitelline ligaments, and these can cause an obstruction to the intestine. The duct may also form a fistula opening on to the anterior abdominal wall. In addition the duct may persist along parts of its course as vitelline cysts. Occasionally the gut tube may become twisted as a volvulus, thus causing an obstruction.

Hindgut

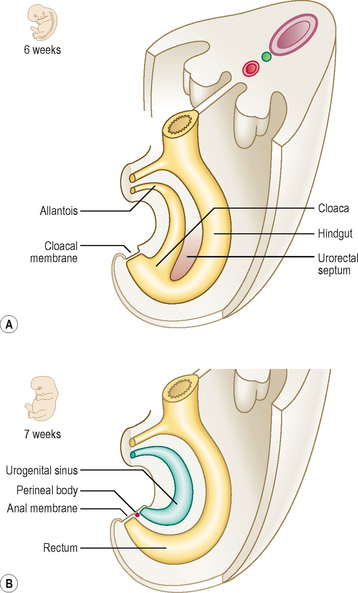

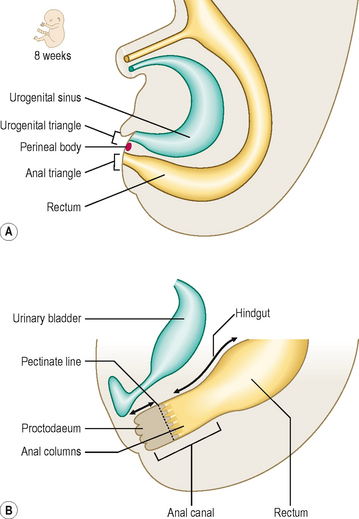

The hindgut is the region of the gut tube lying between a point approximately two-thirds of the way along the length of the transverse colon to the upper half of the anal canal. In addition, the endodermal layer of the hindgut region forms the epithelial lining of the urinary bladder and urethra. Initially, the hindgut opens into the primitive cloaca, which also communicates with the allantois (Fig. 7.14A). A band of mesenchymal tissue (the urorectal septum, Fig. 7.14A) divides the cloaca into a urogenital sinus anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly (Figs 7.14B and 7.15A). The allantois is an unimportant structure in humans functionally. This endodermal tube connects the primitive cloaca to the umbilicus, but it soon becomes a fibrous cord, known as the urachus, forming the median umbilical ligament. In some species the allantois contributes to the formation of the placenta. The urorectal septum completes the division of the cloaca when it reaches the cloacal membrane, and at that point it forms the perineal body. By this means the future perineum is divided into the anterior urogenital triangle and the posterior anal triangle (Fig. 7.15A). The anterior part of the cloacal membrane persists until about the seventh week of development when it breaks down, followed soon after by the anal membrane.

The mucosa of the upper half of the anal canal is derived from hindgut endoderm, whereas the lower half is derived from the ectoderm, the proctodaeum (Fig. 7.15B). At about the end of the seventh week proliferation of the ectoderm occludes the lumen of the anal canal but this recanalizes by the ninth week of development. The pectinate line demarcates the two embryological components of the anal canal. This line is located at the base of the anal columns, and marks a change in the epithelial nature of the lining, as well as the territory of blood and nerve supply, and venous and lymphatic drainage. Thus, the upper half of the anal canal is visceral and the lower half is somatic in origin.

The endoderm germ layer contributes the epithelial lining of the gut tube as well as the parenchyma of the liver (and biliary apparatus) and pancreas.

The endoderm germ layer contributes the epithelial lining of the gut tube as well as the parenchyma of the liver (and biliary apparatus) and pancreas. The gut tube is divided into three regions: the foregut, midgut and hindgut. The foregut comprises cranial and caudal portions: the cranial portion gives rise to the pharynx and is dealt with in Chapter 11. The caudal part becomes the lower part of the oesophagus, stomach and cranial half of the duodenum.

The gut tube is divided into three regions: the foregut, midgut and hindgut. The foregut comprises cranial and caudal portions: the cranial portion gives rise to the pharynx and is dealt with in Chapter 11. The caudal part becomes the lower part of the oesophagus, stomach and cranial half of the duodenum. The midgut endoderm gives rise to the mucosae of the second half of the duodenum, the jejunum, ileum, ascending colon and two-thirds of the transverse colon. It forms a rapidly elongating loop, which results in the formation of the physiological umbilical hernia.

The midgut endoderm gives rise to the mucosae of the second half of the duodenum, the jejunum, ileum, ascending colon and two-thirds of the transverse colon. It forms a rapidly elongating loop, which results in the formation of the physiological umbilical hernia. During this phase the midgut loop rotates in an anticlockwise direction, firstly 90° as the loop enters the umbilical cord, and on its return to the abdominal cavity a further 180°. This takes place between the sixth and tenth weeks.

During this phase the midgut loop rotates in an anticlockwise direction, firstly 90° as the loop enters the umbilical cord, and on its return to the abdominal cavity a further 180°. This takes place between the sixth and tenth weeks.

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box