The Difficult Patient

Perspective

Good interpersonal skills are essential to the maintenance of the patient-physician relationship.1 Although some clinicians have more natural abilities in this area than others do, the myth that these skills are intuitive and cannot be taught is erroneous.2 Teaching of communication and relationship-building skills is now a priority of most medical schools and many primary care specialties.3 Guidelines for teaching and evaluating interpersonal skills within emergency medicine residency programs have been developed.2,4,5 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education identifies professionalism and interpersonal communication skills as two of the six core competencies required in the curriculum of all U.S. residency programs, including emergency medicine, prompting greater interest in research and education in these areas. Although it remains a challenge to measure the effectiveness of these initiatives, innovative curricula on professionalism and communication are being implemented in emergency medicine residencies.6–9

Distinguishing Principles

Difficult patients are often referred to as problem patients, disruptive medical patients, unwanted patients, and, less diplomatically, hateful patients.10 Patients with personality disorders are commonly included in this group because of their rigid, maladaptive personality traits. Difficult patients, however, do not necessarily have personality disorders and may fall into one of several other familiar patient categories (e.g., drug seekers, hostile patients, malingerers, and ED repeaters).

Pathology of the Patient-Physician Relationship

An understanding of the difficult patient-physician relationship is hampered by a tendency to view it as a consequence of some inherent problem with the patient. Physician characteristics and the ED environment also play a role.11–13

Physician Factors

Impaired communication is a common problem in all forms of interpersonal relations and is often exaggerated in the medical setting. Patient satisfaction is highly correlated with patients’ beliefs that clinicians listen to them and understand their requests, coupled with the perceived professionalism of the physician.14,15 Despite this, physicians continue to focus on their own medical agenda, which may differ from patients’ concerns. When confronted with patients who have difficult social situations, physicians exacerbate the problem when they refuse to deviate from their own rigid medical model.

Physicians often have preconceived notions of how patients should behave when they are ill and tend to rapidly categorize them as either the acceptable “truly sick” patient type or the “burdensome, difficult” patient type. Patients placed within the former category are excused for their symptoms, but patients in the latter category are not. Patients may also be judged as difficult when cultural differences or language barriers interfere with the development of a mutual understanding between patient and physician.13

Physician failure to provide sufficient and interpretable information to patients about their diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up evaluation is another area of common communication breakdown. Studies show that in 20 minutes of patient-physician interaction, only 1 minute is reserved for educating patients about the illness.16 Personal biases and prejudices also affect patient treatment.11,12,17 The rapid formulation of an opinion based solely on appearance is a skill that physicians rely on to quickly form a “gestalt” about a patient. This is an essential skill for an emergency physician. To assume that such preconceived notions are influential only in a positive way, however, is unrealistic.18

Emergency Department Factors

The ED is an environment plagued with distractions and frequent interruptions, rarely approaching the comforting atmosphere that many patients expect and deserve.19,20 A sense of urgency and strict time constraints are often present. Patient assessments are sometimes conducted in suboptimal environments, such as hallways. The physician interaction is often perceived to be brief and punctuated by interruptions, which may imply to the patient that the physician does not care or that the evaluation is incomplete.19–22 Patients may enter the encounter frustrated because of a lack of choice about their physicians or facilities and upset because of long waiting times, and physicians may enter the encounter biased by nursing comments or stressed by the prospect of losing control of the department while trying to deal with these particularly challenging patients.13

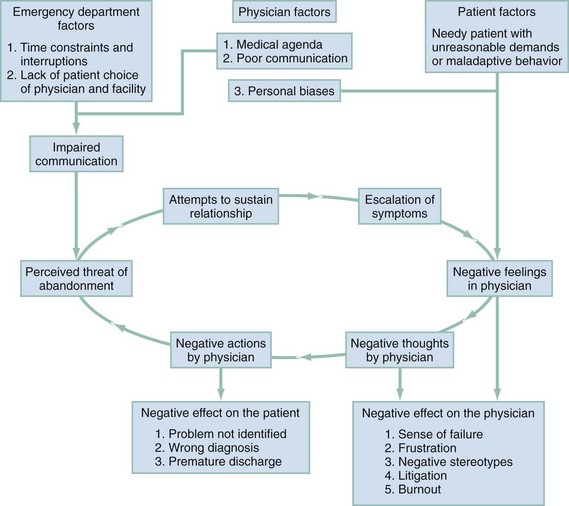

The Cycle of Impaired Patient-Physician Relationships

Difficult patients are often perceived by the physician to be making unreasonable demands (Fig. 189-1). Physicians react with negative feelings and may direct negative actions toward the patient. Patients are sensitive to these negative reactions, feel threatened with abandonment, and attempt to sustain the relationship by escalating symptoms. Physicians experience greater frustration at the maladaptive behavior of the patients, and so the cycle is perpetuated.

The consequences of this impaired relationship for the patient include failure to identify the real problems, missing of medical diagnoses, “another poor experience” with the medical establishment, and premature or inappropriate discharge.23 The negative effect on the staff is manifested by frustration, a sense of failure and defeat, fear of litigation, and the development of unconstructive stereotypes and unrecognized prejudices, all of which may contribute to eventual professional burnout.

Strategies for Treatment of the Difficult Patient

General Strategies

Box 189-1 lists several general strategies that are helpful in dealing with difficult patients.

Be Supportive

Being supportive is not always the natural response to difficult patients because of the negative feelings they arouse in the physician. Nevertheless, initiating the interaction with a clear and explicit demonstration of concern and empathy may be the single most powerful tool at one’s disposal. Some physicians are concerned that seeming to be “soft” with a demanding or entitled patient may exacerbate the situation. To the contrary, expressing a respectful and empathetic concern for their problem effectively disarms many patients who are preparing for a long and arduous battle to be taken seriously. The possible news that there is no immediate solution available is more willingly received by patients who are convinced that they have been heard and believe the physician’s desire to help is sincere.24

Understand the Patient’s Agenda

Sometimes physicians ask themselves, Why is this patient here?1 It is often productive to ask the patient the same question in a nonjudgmental fashion. The patient may have an easily satisfied although unanticipated agenda. This may be as simple as needing a bus ticket to get home or reassurance that there is no immediate danger of dying of some minor disorder. When the patient’s needs are not as easily met, a clear understanding of the purpose of the visit may allow the opportunity to set more realistic goals.25

Dealing with Negative Reactions

Early recognition of these reactions may, in addition to their diagnostic value, allow the physician to analyze them as the first step in preventing failure in the therapeutic relationship.11–13

Negative Thoughts about the Patient

Inaccurate assumptions about patients based on prejudicial, stereotyped labels are called cognitive distortions.12,26 The following case exemplifies the effect that cognitive distortions can have on clinical decision-making.

Negative Behaviors

Physician behaviors can be the most obvious manifestations of negative feelings and thoughts. Examples include rudeness, sarcasm, and indifference toward patients. A patient may receive an incomplete clinical evaluation, and unnecessary ancillary tests may be performed as an attempt to compensate. Physical or chemical restraint use, administration of naloxone, or the performance of other procedures may be used inappropriately or punitively. Analgesics may be withheld or used sparingly. Faulty communication may result in misunderstood discharge instructions and poor compliance. Impaired patient-physician relationships may lead to a refusal of care, forcing treatment against patients’ wishes or resulting in their leaving against medical advice.27

Although patients can suffer at the hands of physicians, the potential exists for the reverse to occur. Dissatisfied patients with incorrect diagnoses and poor follow-up instructions are prone to initiate successful malpractice suits against physicians. The physician may become the victim of patient violence.28 Negative physician behaviors can also have an effect on the rest of the ED staff. Actions viewed by colleagues as inappropriate can compromise team morale and functioning. Physicians who are feeling angry, demoralized, and stressed may vent their frustrations on team members or consulting services, resulting in a further deterioration of the immediate situation and potential damage to long-term working relationships.

Strategies to Manage Negative Reactions

Six strategies are helpful in managing physicians’ negative reactions toward patients.

Maintain Appropriate Emotional Distance

Physicians should avoid reciprocating hostile reactions offered by patients. This may be difficult to resist and is best accomplished by maintaining sufficient emotional distance to avoid taking the patient’s behavior personally. This “detached concern” should be balanced with sufficient emotional investment to convey a sense of caring and empathy for the patient.11,24

Look for the Cognitive Distortion

Cognitive distortions are best identified by looking for evidence that patients or situations are being stereotyped. Physicians should be aware of the effects on clinical judgment that arbitrary inferences and all-or-none thinking have on interactions with patients.29

Crisis Intervention

Some presenting complaints, such as “can’t sleep,” “nervous stomach,” “anxiety,” and “can’t cope,” are especially likely to produce a sense of frustration and dread among caregivers. Attempts to deal with such complaints directly often prove unfruitful, partly because the patient’s seemingly exaggerated affect interferes with effective communication. These are, however, all signs of a patient presenting in crisis.30

Anatomy of a Crisis

A crisis occurs when a hazardous event is encountered and customary problem-solving strategies prove ineffective.24 People experience crises of various intensities many times in their lives; common examples include the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, serious illness, and domestic violence. The usual response of an individual to such stress is to experience an inner tension that mobilizes coping skills. Different problem-solving behaviors are then tried on the basis of previous experience.

Dealing with the Crisis

Recognizing the Crisis.: The presenting complaint of a patient in crisis may be a description of an event, situation, emotion, or physical symptom that can be vague or specific (domestic violence, inability to cope, anxiety, unwell, headache). Patients who present with crisis-related symptoms are a heterogeneous group. At one end of the spectrum are patients who have chief complaints that describe some type of emotional suffering and who do not require a traditional “medical” workup. At the other extreme are patients who need to be reassured in absolute terms about the absence of serious disease before their anxiety is alleviated. Between these two extremes are patients who partially understand how their circumstances might be contributing to their suffering. They can accept the idea that “the effect of stress often produces these kinds of physical symptoms.” Many patients, however, are justifiably unwilling to accept this explanation until they believe their medical complaint is adequately assessed. This usually requires no more than a careful history and physical examination followed by reassuring communication from the physician and the patient’s perception that the complaint is taken seriously.

Some patients who are in severe crisis need to be taken through the steps of formal crisis intervention. The complex nature and considerable time required for this are often beyond the scope of practice of a busy emergency physician. The unfortunate increase in the length of stay for psychiatric patients in the ED, because of diminishing resources for these patients, may provide an opportunity for social workers, psychiatrists, or psychiatric nurse practitioners to use this technique. A recognition of the patient in crisis is critical to creating a functional patient-physician relationship, addressing the underlying illness, and beginning the process of intervention (Box 189-2).

Gathering Basic Information.: The first step in crisis intervention, after recognition of the crisis, involves gathering general information about the patient’s home environment, work situation, personal relationships, and social involvements. The purpose of basic information gathering is to place the patient and the crisis into context before exploring the crisis itself. This step is time-consuming and cannot be rushed, and it needs to be performed by providers other than the emergency physician.

Understanding the Development of the Crisis.: A structured interview is performed to obtain information about the sequence of events leading up to the crisis and the nature of the crisis itself. The objective is to understand the situation while keeping the interview organized and directed so that the patient can describe events without being overwhelmed by the emotion attached to them.

Reproducing the Peak Tension of the Crisis.: Once the crux of the crisis is identified, the care provider should proceed to help the patient express the intense emotions associated with the situation. Through empathetic, active listening, the person in crisis is allowed to experience the previously overwhelming emotions in a safe context. This places the care provider in a position of trust and sets the stage for problem solving.

Finding the Solution.: In the final phase of crisis intervention, the physician reframes the circumstances in objective, realistic, and understandable terms for all those concerned to facilitate a solution to the problem. Possible solutions to the crisis are then suggested, with participation from the involved parties, and the best plan for resolution is implemented. It is important that this be a joint effort and that the patient have some ownership of the solution.30

Specific Approaches for Dealing with Difficult Patients: Putting It All Together

Behavioral Classification

Individuals with personality disorders frequently present as difficult patients. Although reliably establishing the diagnosis of a personality disorder during the typical brief ED encounter is difficult, an awareness of those personality disorders having a high prevalence in the ED helps ease communication with colleagues when the diagnosis has been previously established (Box 189-3).

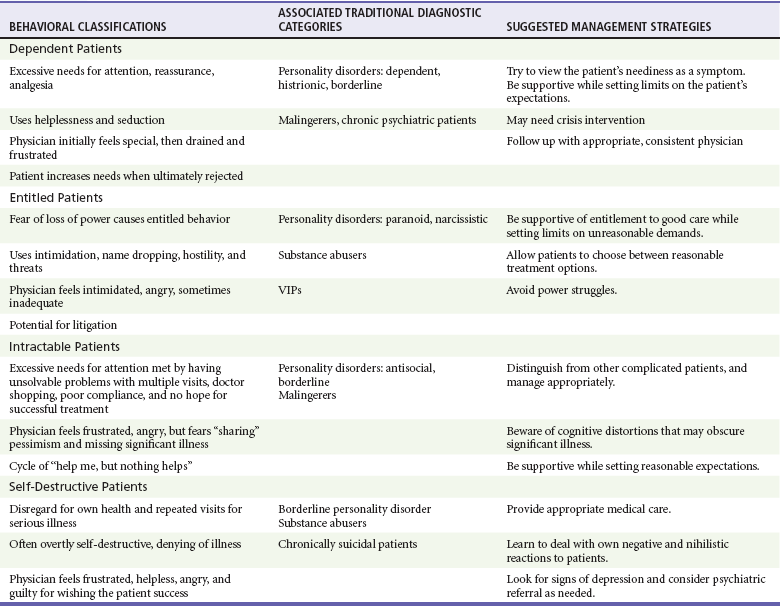

An alternative to the traditional diagnostic categories for classification of difficult patients is based on four specific behavioral presentations and the negative reactions they produce.23,31 To adapt this classification system, with more neutral terms, the behavioral categories are dependent patients, entitled patients, intractable patients, and self-destructive patients. Through recognition of the difficult patient’s maladaptive behavior and identification of the physician’s subsequent negative reactions, patients can be placed into one of these behavioral categories. The behavioral categories in turn suggest effective treatment strategies for each patient type (Table 189-1).

Dependent Patients

Dependent patients see physicians as inexhaustible sources of compassion and understanding. Their initially reasonable requests rapidly escalate into repeated demands for reassurance, affection, analgesia, or other forms of attention. They are excessive in their gratitude; however, the more care they receive, the more their needs multiply. Initially, the physician may feel powerful and unique. Dependent patients give the message “You’re the only doctor who cares,” and the physician often believes it. As the demands escalate, the physician’s patience diminishes and initial feelings of inflated self-esteem are replaced with feelings of frustration, exhaustion, and failure. This leads to a natural desire to discharge or refer these patients, along with their demands, to another unfortunate physician. The patient leaves feeling rejected and then begins the same vicious circle with the next physician. Patients with certain personality disorders (dependent, borderline, and histrionic), somatoform disorders, malingering, and chronic psychiatric disorders often fall into this behavior category.32

Entitled Patients

Entitled patients also seem to have endless needs, but instead of helplessness or seduction, they use intimidation, hostility, and threats to attain their often unreasonable demands. Entitled patients fear being helpless and dependent on physicians. They use a shield of entitlement to protect themselves. An example is the lawyer who, in his refusal to accept his illness, roams from physician to physician demanding repeated tests and opinions while threatening to sue the previous physician who had tried to help him. Physicians experience the natural responses of disgust, anger, and antagonism when they are faced with such patients. There may be an urge to enter into a power struggle with the patient. The other common temptation is to accept the patient’s terms at the price of compromising his or her care. On occasion, the physician may even experience shame at being unable to meet the patient’s unrealistic demands. The maladaptive behaviors of entitled patients are commonly seen in people with paranoid and narcissistic personality disorders as well as in addicted patients and VIPs.32

Intractable Patients

Intractable patients, like dependent and entitled patients, have insatiable needs for emotional support. They are, however, neither seductive nor dependent in their behaviors. They present the antithesis of entitlement; they believe nothing will help. Intractable patients desperately seek help despite the failure of all previous medical assistance. Their history is punctuated by multiple emergency visits and behaviors that are self-defeating, covert, and manipulative. These negative behaviors undermine treatment and antagonize physicians, creating feelings of anger, self-doubt, and frustration. Patients with borderline and antisocial personality disorders and malingerers often fall into this behavioral category.32

Malingering represents deceptive, manipulative behavior and is coded in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), as a “problem” rather than a mental disorder.32 This contrived behavior should be distinguished from the psychiatric illness of somatoform disorders. Somatization is the involuntary production of symptoms without the patient’s awareness. Unlike malingerers, somatizers are not motivated by any conscious desire for secondary gain.33

Repeaters are patients who frequent the ED excessively to the point that most staff know them by name. Although chronic schizophrenics often fall into this category, this behavior can occur in any patient with poor coping skills and maladaptive responses to psychosocial stressors. The easy accessibility of the ED often makes it the only support system immediately available to chronically decompensated patients. Despite the perception that “frequent flyers” are often inappropriate in their ED use, studies demonstrate that frequent users are in poor health and require medical attention more often than less frequent users.34,35

Nevertheless, limits should be set regarding patients’ expectations. Physicians should use this strategy while acknowledging the difficulty of the patients’ problems and sharing their deep concern, and perhaps even pessimism, about the outcome of the investigations and treatment. It is helpful to make statements such as, “You know, Mr. Jones, you obviously have a very difficult problem here. You’ve seen lots of doctors and had lots of tests and treatments that don’t seem to be helping much. There is no way, given the limited resources available in the ED at 11 o’clock on a Friday night, that we are going to be able to get to the bottom of this. What I can do is examine you and do some tests to make sure that there is no new, serious problem going on tonight. Then you will be able to follow up with your regular doctor on Monday.” In this way the physician can communicate both an interest in the patient and empathy for the patient’s condition while setting limits on expectations. Both the physician and patient then understand the “contract” and have a way of terminating the encounter satisfactorily.25

Self-Destructive Patients

Self-destructive patients are particularly difficult to treat. Unlike intractable patients, they do not seek help. Rather, they are repeatedly brought to the ED because of their neglectful and self-destructive behaviors. Their ability to deny their problems is profound and sets up the maladaptive cycle of “nothing is wrong and nothing will help.” Yet their behaviors often require repeated heroic efforts to save their lives. Their chronic self-destructive behaviors may temporarily meet their immediate needs of shelter and food and perhaps, paradoxically, some of the attention they outwardly reject. This lethal cycle usually leads to a premature death. The substance abuser, the violent patient, and the suicidal patient are included in this category of difficult patient.10

It is not surprising that ED staff respond to such patients negatively, feel frustrated and helpless, and may even secretly wish them success in their self-destructive efforts. These are among the most difficult patients to treat. In reality, physicians can do little apart from providing appropriate care for the multiple presentations characteristic of this type of patient. The greatest obstacle for physicians may be to come to terms with their own complacency about the survival or demise of such patients. The lack of real concern about whether they live or die, or worse, actually wishing that they would die, is repugnant and produces feelings of self-recrimination. Our inability to relate to the self-destructive decisions made by these individuals contributes to our complacency about their plight. Remembering our own human weaknesses or risk-taking behaviors and viewing their seemingly incomprehensible behavior as a difference in degree rather than in kind may help us to have more empathy for them.11 Being supportive is important. Signs of depression in the patient may indicate the need for psychiatric referral. These patients should be screened for risk of suicide and, when appropriate, held for psychiatric evaluation after medical stabilization.

Summary

Dealing with difficult patients is a common problem in the ED. The impaired patient-physician relationships associated with them have multiple negative implications for both patients and physicians. Their treatment may be optimized by use of the general principles discussed in this chapter, by dealing realistically with one’s own negative reactions, and by use of techniques of crisis intervention when it is appropriate. These strategies are best applied within the context of a behavioral classification that avoids pejorative terms and stereotypes, labels that differentiate them from “worthier” patients.11 Although this approach is not a panacea for dealing with difficult patients, the framework may help physicians render appropriate care while minimizing personal frustration, medicolegal exposure, and eventual physician burnout.

One of the great challenges of medical practice is to maintain humanity when caring for these difficult and highly vulnerable individuals. By focusing on their humanity, we have the best chance of preserving our own.11 It is easy to care for patients who generate sympathy and noble to care for those who do not.13

In the end, the ability to accept distressing behavior as a symptom and to treat even the most irritating individuals with compassion and kindness may be the key to surviving them. When asked how he had avoided burnout after decades in emergency medicine, one well-known patriarch of the specialty simply responded, “You’ve got to love the patients.”36 This is a tall order, and not meant in the literal sense. But the degree to which we can show caring and empathy, even to the unlovable, may be the key to maintaining the quality of our care, our satisfaction with the specialty, and our long-term survival in practice.

References

1. Rhodes, KV, et al. Resuscitating the physician-patient relationship: Emergency department communication in an academic medical center. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:262.

2. Hobgood, CD, Riviello, RJ, Jourilles, N, Hamilton, G. Assessment of communication and interpersonal skills competencies. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1257.

3. Yedidia, MJ, et al. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA. 2003;290:1157.

4. Larkin, GL, Binder, L, Houry, D, Adams, J. Defining and evaluating professionalism: A core competency for graduate emergency medical education. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1249.

5. Falvo, T, McKniff, S, Smolin, G, Vega, D, Amsterdam, JT. The business of emergency medicine: A nonclinical curriculum proposal for emergency medicine residency programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:900.

6. Van Groenou, AA, Bakes, KM. Art, chaos, ethics and science (ACES): A doctoring curriculum for emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:532.

7. Gisondi, MA, Smith-Coggins, R, Harter, PM, Soltysik, RC, Yarnold, PR. Assessment of resident professionalism using high fidelity simulation of ethical dilemmas. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:931.

8. Knopp, R. The challenges of teaching professionalism. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:538.

9. Welch, SJ, Slovis, C, Jensen, K, Chan, T, Davidson, SJ. Time for a rigorous performance improvement curriculum for emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:783.

10. Disruptive medical patients. In: Hyman SE, Tesar G, eds. Manual of Psychiatric Emergencies. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994.

11. Croskerry, P. The affective imperative: Coming to terms with our emotions. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;14:184.

12. Croskerry, P. Achieving quality in clinical decision making: Cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1184.

13. Adams, J, Murray, R. The general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16:689.

14. Brown, AD, Sandoval, GA, Levinton, C, Blackstien-Hirsch, P. Developing an efficient model to select emergency department satisfaction improvement strategies. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:3.

15. Taylor, C, Benger, JR. Patient satisfaction in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:262.

16. Waitzkin, H. Doctor-patient communication: Clinical implications of social scientific research. JAMA. 1984;252:1441.

17. Birdwell, BD, Herbers, JE, Kroenke, K. Evaluating chest pain: The patient’s presentation style alters the physician’s diagnostic approach. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1991.

18. Croskerry, P, Abbass, A, Wu, AW. How doctors feel: Affective issues in patients’ safety. Lancet. 2008;372:1205.

19. Fairbanks, RJ, Bisantz, AM, Sunm, M. Emergency department communication links and patterns. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:396.

20. Tijunelis, MA, Fitzsullivan, E, Henderson, SO. Noise in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:332.

21. Murphy, A. To sit or not to sit: A question of cultural performance. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:194.

22. Cramm, KJ, Dowd, MD. What are you waiting for? A study of resident physician–parent communication in a pediatric emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:361.

23. Strous, RD, Ulman, A, Kotler, M. The hateful patient revisited: Relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:387.

24. Lin, C, Hsu, MF, Chong, C, Differences between emergency patients and their doctors in the perception of physician empathy: Implications for medical education. Education for Health 2008;21:1. www.educationforhealth.net.

25. Drossman, DA. Psychological sound bites: Exercises in the patient-doctor relationship. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1418.

26. Croskerry, P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to prevent them. Acad Med. 2003;78:1.

27. Simon, JR. Refusal of care: The physician-patient relationship and decision-making capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:456.

28. Kowalenko, T, Walters, BL, Khare, RK, Compton, S. Workplace violence: A survey of emergency physicians in the state of Michigan. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:142.

29. Croskerry, P. Critical thinking and decision-making: Avoiding the perils of thin-slicing. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:720.

30. Kercher, EE. Crisis intervention in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1991;9:219.

31. Groves, JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;296:883.

32. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

33. Larkin, GL, et al. Mental health and emergency medicine: A research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1110.

34. Hunt, KA, Weber, EJ, Showstack, AJ, Colby, DC, Callaham, ML. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:1.

35. Bernstein, SL. Frequent emergency department visitors: The end of inappropriateness. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:18.

36. Harrison, DW. Emergency medicine as a martial art. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;17:115.