The developing world

Malaria

Pathogenesis

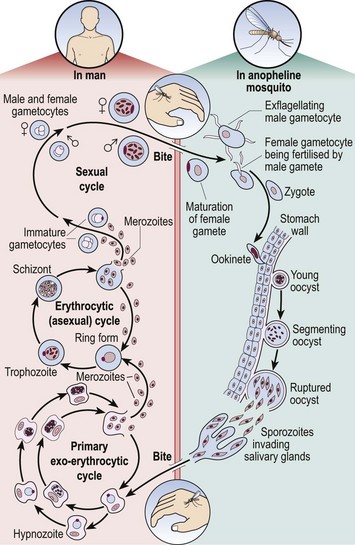

The life cycle of the malaria parasite is illustrated in Figure 49.1. When taking a meal of blood an infected mosquito initiates human infection by the inoculation of malarial sporozoites. These rapidly pass to the liver where they enter hepatocytes and divide. After several days, enormously increased numbers of parasites (merozoites) depart the liver and invade red cells. Here the merozoites develop via ring forms and trophozoites into schizonts. Rupture of the schizont releases 12–20 merozoites back into the blood, thus perpetuating the cycle. The duration of the blood cycle varies between malarial species, explaining the different periodicity of fever in each type. A further mosquito becomes infected when it feeds on blood containing gametocytes, the sexual form of the parasite.

Diagnosis

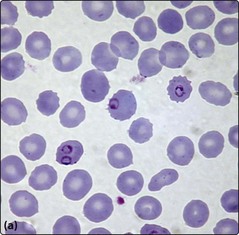

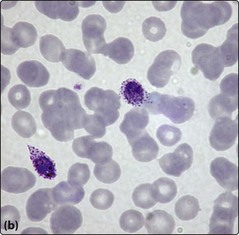

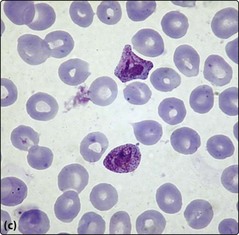

Although malarial parasites may be detected in normal blood films, their identification is generally easier in Leishmann or Giemsa stain at a higher pH. A thick film is best for detection and a thin film for determination of the species. Prolonged inspection of the film is sometimes necessary to spot malarial parasites as there can be a low level of parasitaemia. Where malaria is suspected on clinical grounds repeated samples may be needed to make or exclude the diagnosis. P. falciparum is often associated with higher parasite counts. Paradoxically, some very ill patients with malaria initially have no detectable parasites in the blood as there is sequestration of parasite-laden red cells in the tissues. It is beyond the scope of this book to make a detailed comparison of the four species but some typical appearances are shown in Figure 49.2. Supplementary methods of parasite detection include antigen and antibody detection and DNA-based techniques.

Clinical features

Malaria has a different clinical presentation in non-immune and immune patients.

Other parasitic diseases detectable in the blood

Filariasis. Microfilariae are released into the blood during an acute attack of disease. As the organisms are motile, examination of a wet preparation is useful.

Filariasis. Microfilariae are released into the blood during an acute attack of disease. As the organisms are motile, examination of a wet preparation is useful.

Babesiosis. This tick-borne disease only occasionally affects humans. Trophozoites which resemble small ring-forms of P. falciparum can be found in red cells.

Babesiosis. This tick-borne disease only occasionally affects humans. Trophozoites which resemble small ring-forms of P. falciparum can be found in red cells.

Trypanosomiasis. The parasites are extracellular and motile.

Trypanosomiasis. The parasites are extracellular and motile.