Chapter 5 The context of risk

Knowledge and clinical skill are helpful but do not inoculate the clinician against the discomfort of uncertainty.1

Clinical risk assessment should be motivated primarily by the intention to provide a patient with better treatment and care.2

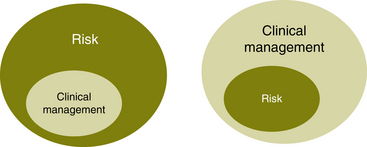

These two positions can be shown diagrammatically, as seen in Figure 5.1.

Other contextual factors are not necessarily related to the patient or the relationship that the clinician has with the patient. There may be personal factors with the clinician, dynamic problems within the clinician’s team and difficulties accessing resources in which to manage the risk.

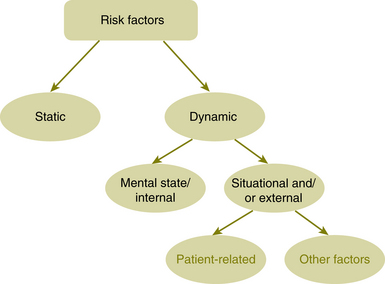

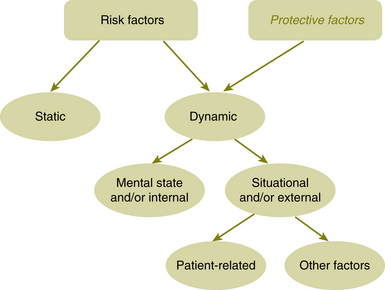

It is necessary to expand the previous thinking about the dynamic situational factors and divide these into patient-related factors and non-patient related factors (see the flow chart in Figure 5.2).

In the ‘other factors’ circle, consideration can be given to other issues that may influence the risk and the outcome. These may include:

• situational factors that are not directly related to the patient but are more related to the wider social environment, such as culture, ethnicity, religion, psycho-social influences, and so forth

• physical environment concerns; for example, the layout of an inpatient ward, whether a potentially violent patient is being seen in a forensic setting or in their home, and so forth

• personal (clinician) responses to the risk (see Chapter 6)

• multidisciplinary team (MDT) and other systemic responses to the risk (see Chapter 7)

• resources available for managing the risk and the clinical condition.

Cultural, ethnic and psycho-social factors affecting risk

• Religion. Religion has long been linked to causation of violence, to war and to suicide. Over thousands of years, wars have been fought in the name of religion and this continues today. Terror sects fight in the name of religion and some religions have fanatical offshoots in which violence is sanctioned. Other religious groups in the last five decades have been associated with mass suicide; for example, the Jonestown mass suicide in 1978.3

Religion can also be linked to protective factors. Catholicism classically was perceived as being a protective factor for suicide. It is generally recognised that a strong faith does protect one from suicide to a certain extent.4

• Ethnicity and psycho-social influences. Certain ethnic groups in different countries have a higher risk of completed suicide. Dependent on country, different ethnic groups may be more vulnerable.5 There are also some ethnic groups in which alcohol use is problematical and this can be linked to increased risk of suicide.6 It pays to take note of regional ethnic variations related to risk. Some indigenous populations are at higher risk of suicide. In 1995, a Royal Commission Report estimated that suicide rates across all age groups of Aboriginal people were on average about three times higher than in the non-Aboriginal population.7 Recently, a high female suicide rate in China has been noted and is considered to be related to particular pressures on women in modern Chinese society.8

A particular example of violence linked to ethnicity is the rate of female feticide (the death of a fetus) and infanticide in India as a result of the preference for boy children.9

• Cultural stigma. In some cultures, there may be cultural distrust and stigma associated with health-seeking behaviour.10 This may occur especially in Third World countries when Western practices are introduced.

• Refugees. This group can also be very vulnerable. High rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in refugees11 and difficulty integrating with different cultural mores can raise risk.

Particular forms of risk behaviour can also be culturally determined. For example, self-immolation (burning of oneself) in India is heavily weighted towards women in the age group 15–34.12 This is not necessarily related to any religious belief but possibly a function of societal belief structures. It is also necessary to consider local cultural variations which may have a bearing on risk. For example, it is not unusual for gangs to congregate in certain cities and towns. Considering gang affiliation and whether there is a subculture of sanctioned violence will be of relevance.

The physical environment of risk

When a patient in whom there is a risk of violence is interviewed, is this undertaken by a clinician on their own sitting nearest the door? For a suicidal patient, does the physical layout of the ward enable unobtrusive observation to occur? In virtually every clinical situation, the physical environment will be of some importance.

This topic will be covered in more detail in Chapter 12, Risk management.

1 Miller M.C., Tabakin R., Schimmel J. Managing risk when risk is greatest. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:154–159.

2 Mullen P.E. Dangerousness, risk and the prediction of probability. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford.: Oxford University Press; 2001.

3 Reiterman T., Jacobs J. Raven: The Untold Story of Rev. Jim Jones and His People. Boston.: EP Dutton Publishers; 1982.

4 Goldney R.D. Suicide Prevention. Oxford.: Oxford University Press; 2008.

5 Bhui K.S., McKenzie K. Rates and risk factors by ethnic group for suicides within a year of contact with mental health services in England and Wales. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(4):414–420.

6 Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol and suicide among racial/ethnic populations in 17 States, 2005–2006. MMWR — Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(23):637–641.

7 Suicide among Aboriginal People: Royal Commission Report. Prepared by Nancy Miller Chenier. Political and Social Affairs Division, 23 February 1995.

9 Sumner M. The unknown genocide: how one country’s culture is destroying the girl child. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2009;15(2):65–68.

10 Goldston D.B., Molock S.D., Whitbeck L.B., Leslie B., Murakami J.L., Zayas L.H., Gordon C.N. Cultural considerations in adolescent suicide prevention and psychosocial treatment. American Psychologist. 2008;63(1):14–31.

11 Corales T.A. Trends in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Research. Nova Science Publishers. New York: Hauppauge; 2005.

12 Sanghavi P., Bhalla K., Das V. Fire-related deaths in India in 2001: a retrospective analysis of data. The Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1282–1288.