Chapter 6. The collectivity of healthcare: multidisciplinary team care

Eileen Willis, Judith Dwyer and Sandra Dunn

Introduction

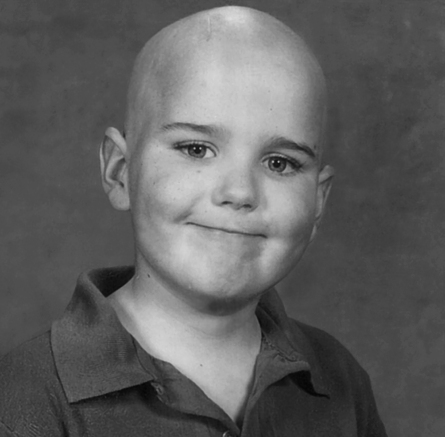

Threaded through this discussion are excerpts from a case study of the care of a single child with brain cancer (‘Teamwork for Keown’) presenting the perspectives and insights of four members of this family’s healthcare team in ways that we hope illustrate the major themes in current thinking about teamwork in healthcare. We use both a narrative and thematic approach drawing on the experiences of: a paediatric oncologist; a paediatric palliative care nurse practitioner; a physiotherapist with experience in paediatrics, oncology, adult rehabilitation and domiciliary care teams; and Sandra, mother of five children and professor of nursing. Professor Sandra Dunn is an author of this paper in both capacities, and her family has consented to this use of Keown’s story.

In 1998 Keown, Sandra and James’s youngest child, was diagnosed with medulloblastoma, cancer of the brain. He died in 2003 at the age of 10. Interviews and thematic analysis were conducted by the first two authors following ethics approval and focused on the participant’s experiences and beliefs about client/family-centred multidisciplinary care. The framing of these interviews was based on a review of the literature and a reading of the narrative account presented by Sandra, although the focus of the interviews was not on Keown exclusively, but rather on teamwork more generally. We use the case study to remind the reader that in the last analysis the organisation of clinical treatment is about dealing with human need and suffering. The first narrative of the case study is below.

Box 6.1

Sandra: On 15 August 1998, aged five years and four months, Keown James Dunn, my youngest son, was diagnosed with a medulloblastoma, cancer of the brain. In the coming years my husband and I learned more than we ever wanted to know about the paediatric oncology experience – from the parent’s side of the looking glass.

Keown had had maybe a year of occasional morning headaches, sometimes vomiting – not enough to get much attention in the chaos of getting seven people off to school and work. Then one morning came the call from school – ‘Keown has a bad headache. He’s crying and the light hurts his eyes.’ The nurses in the ER stood with me and my husband, listened to our questions, told us what was said when our ears were too full of fear to hear the doctors’ discussion. Then the CAT scan, the first set of films, the radiologist arriving to inject contrast. For me, it truly started then. Then surgery. There were no real choices. With that presentation, there weren’t options; there wasn’t time.

Post-op … waiting. Did they get it all? Will he wake up? And if he does, will he still be our son? As Keown lay in paeds ICU, the neurosurgeon came to see us, telling us what had happened, reassuring us that the surgery had gone well. The nurses answered and re-answered our questions, the same questions over and over, reassuring, moving with purpose and skill.

After surgery came the looking for answers: How do we help our son? We didn’t even know the questions, let alone the answers.

Teamwork in organisations

The concept of the team is an old one, originally referring to harnessed animals pulling loads together and now used extensively for groups of people playing sport or working together. It implies interdependence, common goals and effort, and its positive meaning is related to the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. A team can be defined as two or more individuals performing a range of interdependent tasks with a clear division of labour (Baker et al 2006). More technically, it is defined as

[A] collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for outcomes, who see themselves and are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more larger social systems and who manage their relationships across organisational borders.

(Cohen & Bailey 1997:241)

Teams can be lasting structures – such as the staff of a dialysis unit or a community health centre – or short-term groups that form to meet the needs of an individual family or situation such as those responding to a local outbreak of infection in a child care centre, or a project team introducing a new system or service.

Over the past several decades attention to teamwork has been a strong component of contemporary management theory with a number of experts suggesting that it contributes to increases in efficiency, productivity, problem solving and workplace creativity (Morris 1996). Management literature in the 1980s and 1990s on the flexible firm and flexible specialisation suggested that teamwork produced flatter structures and a breakdown of the rigid division of labour, bringing the production process closer to the customer and their needs (Mathews, 1989, Mathews, 1991, Mathews, 1992a and Mathews, 1992b, Robbins & Barnwell 2002). As Sutcliffe and Callus (1994:67) note the aim is to enhance the links between the market and the organisation in an arena where technological change increasingly requires more flexible work practices. Two questions arise from this work: first, it is not clear from the literature what exactly it is about teamwork that brings the production process closer to the customer; and second, whether the rationale for team-based work outlined by Mathews, 1991 and Mathews, 1992a and others as suitable for industry is directly transferable or desirable for healthcare settings. Teamwork is after all a means to an end, not a goal in itself, and like all methods, has limits to its application. Further, there are real costs to effective teamwork, and attention must be paid to ensuring that costs are contained and proportional to the benefits (West et al 2002).

Teamwork is the totality of methods of collaboration in pursuit of shared purposes used by members of a team. Given this definition much is made of the importance of multidisciplinary teamwork in healthcare (e.g. Moorin 2005), which is seen as both vitally important and difficult to achieve. It is important because the different professions or disciplines (including specialties within professions) bring different skills and perspectives. These skills and perspectives need to be integrated to ensure that goals and decision making are based on the best available understanding and that commitment to the decisions is shared by team members. However, teamwork is difficult to achieve not only because it requires time and attention to the way people work together, but also because the training of health professionals tends to emphasise individual accountability and skill (and a preference for working with one’s own profession), as do systems for remuneration and reward (Leggat 2007).

What is multidisciplinary team care?

In authentic multidisciplinary care, team members rely on cross-disciplinary input in planning their own clinical care, in the development of a collaborative individual treatment plan for a patient (National Breast Cancer Centre 2003:2), and in emergence of new activities arising from this collaboration. There is a clear understanding of the array of professional expertise, but a willingness to be flexible, to share skills and in some cases to tolerate role substitution, collective ownership of the care plan and a capacity to reflect on these processes. Bronstein (2003:114) extends this to suggest that team members have to see the collaboration as positive and believe that the goals could only be achieved through collaboration with each other. Perhaps more than in other industries, multidisciplinary teamwork in healthcare is achieved through a combination of structural units (such as the oncology unit) and ‘virtual teams’ – the health professionals who work together across organisational units to plan and deliver the care for an individual or a group of patients (such as pharmacists, radiologists, pathologists and others working with the oncology unit).

Box 6.2

Keown’s carers defined multidisciplinary teams as a small core group of professionals, as well as others who may at times form part of the group, but are often on the outer rings. In the acute phase (post surgery), the core team was the oncology unit, along with the pharmacist, radiologist, play therapist and pathologist. They did not regard the patient or his family as core members of the team, but recognised the family’s role in decision making about treatment options.

In the palliative phase, the team is ‘a virtual team’ drawn from those available in the patient’s community – every health professional who can contribute and is willing to work with the team philosophy. In this phase, the family was seen as the centre of the team – the palliative care nurse practitioner saw her role as ‘creating a nest for that family’ while they coped with the reality of their child dying. Perhaps because of their inability to change the course of Keown’s illness, the professionals worried that they may have let Keown’s family down in the palliative phase, but Sandra felt that her whole family had been supported and cared for.

In the professionals’ view the inclusion of patients and their families into the team has emerged at the current time because of the need for the treating team to share the same goals as the patient. They note that sometimes clinicians have goals directed towards a ‘cure at any cost’, while clients may wish to pursue quality-of-life approaches. In such situations decision making requires bringing the client into the team as an equal member, entitled not just to consent to treatment, but to be able to say what treatment is provided and of course to know their treatment options. Keown participated in decisions to do with his own quality of life and brain function. He knew he had bad cells and good cells and that the radiotherapy would attack the bad cells and also damage good ones. At age nine, with the hindsight of seeing other children, he said to his parents, ‘I don’t want to do that, I don’t want to be like X (who had a brain injury from treatment); I know I can die from this, but if all the good cells are going to die, I don’t want to do that.’

The significant characteristic of MTC is that the various professionals come together to pool their expertise in all relevant aspects of the patient’s care, and together plan a program of care tailored to each patient (Herrman et al 2002; Liberman et al 2001). Why this approach should emerge at this point in history is partly explained by developments in healthcare and in society. Cancer care has been a focus of attention to MTC because it requires a set of complex decisions to be made over diagnosis, treatment options, and efficacy for specific individuals. Chronic illness more generally requires the interventions of an array of health professionals over an extended period. Further, sick individuals are not only clinically specific, they are also patients with rights, and are increasingly well informed.

Some commentators and researchers have used definitions with lower thresholds for multidisciplinarity – any care involving more than one discipline (Britton et al 2006, Karjalainen et al 2007). However, an important criterion in our definition is that the group of health professionals bring their shared expertise to the diagnostic, treatment, rehabilitation and/or care processes. Treatment and care may come from any member of the team at various stages in the patient’s illness. As a consequence senior medical professionals may not always take the lead. Leadership may come from the patient’s GP, their specialist nurse, or dietician (Wilson et al 2005).

Further ambiguity in defining MTC occurs in the Australian context, where team members may work across significant geographical distances. Recognising this, the National Multidisciplinary Care Demonstration Project (NMCDP) in breast cancer developed a set of five essential principles in defining multidisciplinary care (National Breast Cancer Centre 2003:5). These are:

1. a team approach involving core disciplines integral to the provision of good care, with input from other specialities as required (the ‘core’ disciplines are surgery, radiology, medical and radiation oncology, pathology and supportive care)

2. communication occurs among team members regarding treatment planning

3. access to the full therapeutic range for all women, regardless of geographical remoteness or size of institution

4. care is provided in accordance with nationally agreed standards

5. involvement of the woman in decisions about her care.

The limitation of confining the team to medical specialists has been highlighted in the care of patients with cancer, who usually require input from several clinical disciplines in the acute phase, but also in rehabilitation and palliative phases of care (National Cancer Control Initiative 2003).

In the Australian context multidisciplinary care teams can be found in intensive care units (ICUs), cancer and palliative care, in geriatric and rehabilitation services (Karjalainen et al 2007), in crisis mental health teams (Joy et al 2006), in the organisation of care for people with chronic conditions, in aged care and in many other areas. In the UK multidisciplinary teamwork has been endorsed as the major way to organise care for cancer patients (Fleissig et al 2006:935), and in Canada as the major approach to re-structuring the healthcare system in the light of increasing expectations, rising costs and the ageing population (Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) 2006). Multidisciplinary care teams appear to operate best in situations where patients require long-term healthcare interventions across a variety of areas requiring input from a range of professionals, or where care is provided in small and cohesive units such as ICUs or community mental health teams. MTC is also found where diagnosis and treatment are characterised by ambiguity or lack of certainty.

Clinical effectiveness of multidisciplinary team care – the evidence

Evidence on the value of MTC in relevant aspects of healthcare is growing. In a major review of the evidence for MTC in the treatment of cancer, Moorin (2005) reported on 14 studies that provided evidence of reduced mortality and increased quality of life for patients receiving multidisciplinary care. However, some of those studies simply demonstrated the value of the learning curve (that is, better outcomes for those surgeons experienced with and specialising in, for example, breast cancer) and the use of multiple therapies and/or the existence of defined relationships with other disciplines (which may relate to a multidisciplinary team approach) rather than MTC directly (Sainsbury et al 1995). Five of the studies limited the definition of MTC to medical specialists, and one examined the effect of introducing a specialist breast nurse with a role in support and coordination for patients (National Breast Cancer Centre 2003). Several studies examined patient satisfaction and other indicators (such as reduced time to treatment) (Gabel et al 1997) and higher levels of physical functioning (Frost et al 1999).

Proponents of MTC argue that multidisciplinary teams provide benefits for patients ranging from ensuring equal access to specialist services for patients with similar diagnosis, smoother referral between services as communication between treating team members is enhanced, less duplication and delay of diagnostic tests, speedier implementation of treatment plans that conform to internationally accepted standards, less variation in patient survival rates, and increases in the recruitment of patients into clinical trials (Burns & Lloyd 2004, Fleissig et al 2006, Moorin 2005). These and other authors conclude that the benefits are the result of consensus decision making within the team, and a wider awareness of the treatment options available, and in the case of cancer care, possible differences in the staging of treatment (Howard et al 2001). What is clear is that a MTC approach results in increased patient satisfaction arising from enhanced support and a clearer sense of the organisation of care (Fleissig et al 2006, Moorin 2005).

Box 6.3

Sandra began her interview by telling us how terrible the healthcare system is for patients – it is like a machine, set up to serve itself, she said. There is a cost to families in attending, waiting, and undergoing routine tests, and time for ordinary activities is lost. Hospitals appear not to have the capacity to schedule appointments to suit daily life, so that clients have to make daily, but significant adjustments. Sandra found she had to struggle to make the treating team aware of her child’s practical needs, and R∗ and M∗ both saw negotiating between patients and ‘the system’ as one of their primary roles. For Sandra in her role as mother this meant ensuring Keown got to kindergarten to play with his friends irrespective of appointments for radiotherapy, for R it meant rescheduling appointments to reduce the client’s discomfort, costs, and disruption. For M it meant supplying letters of referral when Sandra and her family went on holiday and during the palliative stage in case they might need to call an ambulance or take Keown to the emergency department. In effect the clinical team worked to soften the system, so the family felt cocooned and able to get through the rigours of painful treatment, and then what was going to be a bad outcome. These observations are consistent with the research evidence that patients report speedier services, treatment schedules that reduce waiting times and less impact on their daily lives.

The review by Joy et al (2006) and a similar one by Karjalainen et al (2007) (focused on rehabilitation for neck and shoulder pain among working-age adults), found no differences in clinical outcomes, including deaths, or discernible differences in mental and social wellbeing, and no differences in hospital admissions or repeat admissions pointing to little by way of cost savings. Similarly the studies cited by Moorin (2005:43–44) on cost savings are not conclusive, although Moorin notes that one of the key findings of the Australian National Cancer Demonstration Projects was that costs associated with multidisciplinary team meetings reduce as they become better established. The exception to this is a study done by Ettner et al (2006) who were able to demonstrate that it was cheaper to care for the patients in an intervention (multidisciplinary) group than patients who received ‘usual’ care.

Box 6.4

Sandra: For a child with a medulloblastoma, maybe, on a good day, there might be a 15% chance of survival without any treatment. But these stats are old, and might well be confounded by misdiagnosis or other error. There are no good recent stats on survival without treatment – the study design problems are obvious. So, we are left with old, probably unreliable evidence of a 15% survival rate without treatment.

With each step in treatment there are benefits, but there are also enormous risks. For a child with a medulloblastoma, following neurosurgery alone there may be approximately 45% survival depending on the site, extent and type of tumour. Setting aside those risks associated with any surgery, neurosurgery for cancer risks permanent brain damage (motor control, memory, sensory, cognitive) and hormonal system damage (growth, hunger, diuresis, sexual maturity, etc).

Add radiotherapy to the surgery and survival increases from 45% to around 55 or 60% – survival for two or three more children out of every 20. However, with that improved survival comes more treatment-related risks and side effects: cognitive defects, sensory deficits, secondary cellular dysplasia or cancers, radiation burns, nausea and vomiting. Keown said, ‘Throwing up, Mum. Don’t forget throwing up.’

Chemotherapy. Add 48 weeks of triple therapy and survival increases to maybe 65 or 70% – another two or three kids out of every 20 who get to survive. Additional side effects and risks include death from ordinary childhood illnesses (chicken pox, viruses), renal damage, major hearing loss, sterility, cardiac damage, vomiting and hair loss. The cumulative effects of treatment – a 70% chance of survival and certainty of complications.

Keown is sick, he is tired, he looks funny. He can’t go to school much of the time. He can’t play with his friends. If we go out anywhere, we take along a throw-up bag and a pee bottle because he’s also got diabetes insipidus. ‘Will this kill the bad cells, Mummy?’ ‘I don’t know, my love.’

We are not doing something merely for the sake of action. Every decision carries with it enormous risks and we must balance the benefits with those risks. And the risks are to my son, and my family, and I love them very much. What does this evidence tell me about Keown? Not enough. How do I balance a 15% increase in survival with a 60 to 75% risk of him having a developmental delay?

So I followed the evidence, I followed the European Consortium on their trials. I called Dr X in the United States and asked him if he had any unpublished results for his low-dose radiation/long-term chemo regime. We could not choose survival at any price. So we went with low-dose radiotherapy and long-term chemo. We traded an unknown percentage of survival for a different, but still unknown, percentage of life – quantity for quality – the lady or the tiger – never knowing what was behind either door – the terror of getting it wrong. ‘I wouldn’t do it if it was my son’ said one healthcare professional. ‘If only it were your son’, I thought.

Sandra is clear that the health professionals can’t be expected to make the value judgments needed to choose the treatment that is best for any individual. That choice is the right and responsibility of the patient and his or her family. The paediatric oncologist and the nurse practitioner believed just as strongly that it’s not fair to patients to present them with treatment options without a clear explanation not only of the costs and benefits but also of why this decision needs to be made now, and a clear recommendation. They saw it as an ethical responsibility – to give advice, and not to leave the family potentially with ‘blood on their hands’. Two different, but reconcilable, perspectives.

MTC and psychological wellbeing

While the jury is out on the clinical and cost effectiveness of MTC, the evidence on the value for the psychological wellbeing of clients is overwhelmingly positive. In the studies by Joy et al (2006) and Karjalainen et al (2007), not only did participants report improved wellbeing, their families also reported less disruption to their lives and higher levels of satisfaction with the care provided. In the Joy et al study, this was despite the fact that sick clients continued to live with their families during their illness episode. The National Demonstration Project in Breast Cancer (Moorin 2005:37) study found improvements in the women’s mental health, and significantly, major improvements in decision making by the women. In our own interviews client decision making was a major issue for both the client and the clinicians. We report on the participant’s views below.

The patient and family as ‘partners’ in care?

The management research on teams suggests that team structures allow the production process to be brought closer to the customer and their needs (see Box 6.5). The research on patient satisfaction and the care process suggests that one of the major benefits of MTC is that it can clarify and improve the relationship between patients and families and their care providers. The sense that the input of the various professionals is coordinated, and that the organisation is taking responsibility for that coordination, is important for managing client relationships in any professional business, and no less in healthcare.

Box 6.5

There was a surprising consistency between the four participants in our case study on how patients might exercise their decision making within the team, and how health professionals might facilitate this. The physiotherapist, drawing on her work with clients in rehabilitation, saw it as a duty of care to ensure that they made realistic decisions and set reachable goals. To do this required taking time out to inform patients of all the treatment options and the available evidence and also allowing for mistakes where this could be accommodated – in her experience clients sat in on team meetings and took an active role.

The oncologist similarly noted the need to take time to bring patients into the decision making as partners regardless of the additional time or effort required. He did not see this as ensuring they had the same scientific knowledge, but rather ensuring they understood the nature of the evidence and its limitations and were agreed on the way forward as a family unit, without family divisions or regret. For both the oncologist and the nurse practitioner, this required sharing their own knowledge about the patient’s condition, providing the range of options, explaining their own recommendations and reasoning, but clearly outlining other options. As one noted, ‘Few parents have the capacity to weigh the numbers on risks and benefits; they want their kid to “have a chance” – they are not able to reflect on statistics.’

This approach brings the patient into the decision-making team, but consistent with the principles of MTC does not leave one member totally alone in their choices. Sandra noted that she never felt abandoned by the clinical team in making decisions, but at times she did defer to them; at other times she went against individual clinicians’ recommendations.

Much of the rhetoric about patients and families as ‘partners in care’ has been just that – rhetoric driven by public relations goals and enthusiasm rather than a substantive change in the way the health system and its staff relate to and engage patients in their care. The case for such engagement has a particular logic when the patient is a sick child, and when the episode of care extends beyond the acute phase. Parents are in fact involved in looking after their children and managing their care both in hospital and in the community. Children’s hospitals have recognised this reality for many years, and have changed some aspects of their care in response (such as the ‘negotiated care’ philosophy at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead (Children’s Hospital at Westmead 2005:29)). We suggest that greater recognition, and to some extent formalisation, of the active roles of patients in managing their disease, in achieving their personal goals for life with their disease, and in coordinating the care for sick family members, would improve the relationship between healthcare teams and patients, rather than simply complicate care. This is one of the benefits of MTC that could be better utilised, as we hope our case study of a particularly well-informed ‘partner’ family (Keown’s story) illustrates.

What makes for effective multidisciplinary teams?

While research on the benefits of MTC continues, the model has been strongly embraced by health and medical authorities such as the Royal Australian College of Surgeons, the National Health and Medical Research Council and National Breast Cancer Centre (Moorin 2005). For example, the Australian Council on Safety and Quality in Healthcare states that: ‘A culture of safety in healthcare will be reflected in a system that … supports multidisciplinary team approaches’ (ACSQHC 2000:25). This raises the question of how MTC might be implemented more broadly.

Effective performance of multidisciplinary teamwork in complex healthcare settings depends on four major prerequisites: the structures within the healthcare system (policy and funding mechanisms) that would allow MTC to flourish; systems and procedures within health organisations that nurture teams; the process employed by the team itself; and the qualities of individual team members (Liberman et al 2001, Moorin 2005). We turn first to examine structural factors.

Structural and financial factors

We found little literature that explored the structural barriers to the development of MTC although a cursory examination of where the bulk of the research literature comes from might provide a clue. While the range of English-language clinical studies appeared to be spread proportionately across the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, the majority of government-funded and -commissioned reports emanated from those countries with robust public health services providing free-to-the-consumer or subsidised healthcare. This is not to suggest that nations with universal health services are able to experiment with MTC without dealing with structural barriers, but it does point to the capacity to make national policy directives and to implement strategies to overcome the structural impediments of fee-for-service market-based health systems.

For example Moorin (2005) reports on a number of developments at the national level in Australia, New Zealand and the UK that facilitate the development of MTC. These developments include national policy and priority setting, funding of demonstration projects, and reimbursement to doctors and other health professionals for engaging in MTC. The British National Cancer Collaboration funded the formation of networks made up of private providers, trusts, health authorities, local authorities and the voluntary sector for the treatment of patients with cancer. One of the major outcomes of these network projects was a reduction in waiting times and an increase in patient satisfaction with the service for patients receiving treatment from multidisciplinary teams. This attractive outcome for government ensured that MTC became a standardised approach to cancer treatment in all cancer networks in the UK. Similar national policy directives in Australia have assisted in the development and routinisation of MTC. For example in 1996 cancer was identified as one of seven national health priorities. The National Health Priority Report published in 1997 noted the importance of MTC, as did the 2003 report (Moorin 2005:17).

On the other hand, in Australia, fee-for-service Medicare payments were found to encourage the sequential referral model that moved the patient from GP to a private specialist with little incentive for cross-referrals (because of risk of loss of income) and less incentive to engage in time-consuming MTC (Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee 2005:128). Remuneration methods for allied health professionals in the private sector are also generally not structured so as to enable participation in multidisciplinary team activities. There is little doubt that government funding for innovation assists MTC practices to become routinised in public hospitals and health services and it is not surprising that the major developments in MTC have occurred in the public sector. Access to MTC for rural and remote patients is a related problem.

The introduction of Enhanced Primary Care (EPC) items in the Medical Benefits Schedule (the list of fee-for-service payments that can be claimed from Medicare) is another important example of efforts to remove structural barriers to MTC. These items enable GPs, and their practice nurses, to engage with other service providers in planning and coordinating the care of older patients with chronic conditions. An item specifically for leading or participating in a multidisciplinary case conference to plan care for cancer patients has also been recently introduced, and other items support such activities for various specialties in caring for complex patients.

Lack of substantive research on the economic benefits of MTC is also a major impediment to implementation across the public and private sectors. The evaluation of the National Multidisciplinary Care Demonstration Project (NBCC 2003) found costs were higher for new initiatives, that the costs of personal time to attend meetings needed to be factored into the overall funding estimates, but that average costs per staff per meeting tends to reduce as the programs become established, especially if existing facilities and resources are used.

Organisational systems and process as enablers to MTC

Supportive policy and health structures are necessary but not sufficient requirements for effective multidisciplinary teamwork. Teamwork is also highly dependent on the systems in place within health units, and clearly articulated procedures and protocols outlining the roles, goals and functions of each team member or unit (Grumbach & Bodenheimer 2004, Liberman et al 2001). Baker et al (2006) refer to the high need for synchronisation of tasks across the hypercomplex system of hospitals as ‘tight coupling’. The work of the various professional groups is highly interdependent and interlocked and the systems in place within hospitals need to support this.

Fleissig et al (2006) and Herrman et al (2002) report on difficulties with team processes. They found disaffection within multidisciplinary teams about leadership and decision making with significant gaps between team decisions and the treatment followed by clinicians, reluctance on behalf of clinicians to change their mind on management of the patient, and poor recording of decision making. This last factor points to the need for teams to have sufficient administrative support. The evidence points to a need to schedule meeting times on a regular basis, and this in turn is dependent on organisational factors supporting MTC, such as protecting meeting times from competing events and of course finding a regular time that everyone can attend. Where meetings require tele- or video-conferencing then technical support needs to be readily available. Invariably these requirements point to a need for adequate funding, a major issue for optimum MTC. An additional finding of the National Multidisciplinary Care Demonstration project was resistance by some clinicians to put the psychosocial issues of clients on the agenda (Moorin 2005).

Box 6.6

According to the professionals we interviewed, effective teams:

▪ are ideally geographically collocated with opportunity for regular contact time

▪ quarantine time for regular meetings

▪ need continuity in membership to achieve full capacity for care

▪ are resourced for the costs of working as a team (including administrative support)

▪ have some opportunities for relaxed time together, like ‘first Friday drinks’

▪ make benefits like staff development opportunities and conference attendance available to all professions.

Dynamics within the team

The dynamics of team meetings to a large extent depend on inter-professional respect for the role each discipline plays in the care of the client. The highly regulated division of labour represents one of the processes of teamwork (Mickan & Rodger 2000). It provides clear guidelines for role differentiation, leadership responsibilities and levels of accountability which in turn are reflective of a highly organised culture (Baker et al 2006, Herrman et al 2002, Mickan & Rodger 2000). Where health professionals operate according to and within the bounds of their professional expertise, roles are clear, conflict can be resolved and the possibility of adverse events is contained. The practicalities of this inter-professional collaboration are reflected upon by the oncologist we interviewed (see Box 6.7).

Box 6.7

Reflecting on his early training the oncologist talked frankly about his first experience of a nurse telling him what he needed to do for a child (initiate IV therapy). He was taken aback at her frank assertiveness, but agreed with her assessment. The ability to communicate assertively is highlighted in the literature as something taught to airline pilots as a way of ensuring teamwork enhances safety (Baker et al 2006). The nurse, observing the child over an eight-hour shift, recognised the clinical signs, however putting in an IV line was the responsibility of junior doctors. In interview the oncologist noted that the difficulty here for the responsible clinician is to accept the observations of other professionals within the team, who pass these observations on for implementation. This does not mean taking the nurse’s observations on faith or that there needs to be a move to role substitution. Medicolegal responsibilities mean that each professional is accountable for their role in treatment, and this in turn requires independent decision making as well as taking up advice when it is given.

However team members are often also required to modify their routines and methods to accommodate the priorities or logistics of others, and to adopt new technologies. Edmondson et al (2001) reported on the learning process of surgical teams that were introducing a new method of cardiac surgery. They found it was factors at the team (rather than hospital) level that made the difference for successful implementation; and that success was based on leader (surgeon) behaviour that encouraged team members to question and adapt established routines to the new technology, rather than treat it as a ‘plug-in’. Members of teams also need to develop processes for effective communication and this is dependent on strong and informed leadership and opportunity for trial and error. A number of authors note that there appears to be an optimum size for effective team management. Four to 12 members is cited by Liberman et al (2001) as the ideal before communication begins to breakdown, although the National Multidisciplinary Care Demonstration Project reported up to 18 participants in care planning meetings (Moorin 2005).

Leadership as an enabler in teams

Leadership in MTC is a major issue in the literature, and no doubt in practice. A number of authors note that senior doctors expect to be team leaders (Herrman et al 2002, Lebrasseur et al 2002, Parker-Oliver et al 2005, Wilson et al 2005). It is often assumed that the professional with the longest educational preparation and highest status and salary automatically should lead the team. Herrman et al (2002) make a distinction between leadership of the team and clinical responsibility, autonomy and authority to perform a particular treatment or exercise in care. They suggest that leadership is earned within the team, while clinical responsibility arises out of education and accreditation, and the two qualities should not be confused (Bronstein 2003, Lebrasseur et al 2002, Parker-Oliver et al 2005).

Haward et al (2003) conclude that the most effective teams are those with shared leadership for clinical decision making and Liberman et al (2001) suggest that a case manager is the ideal project manager for the team. They note that leadership of multidisciplinary teams in large organisations like hospitals is presumed to be the responsibility of the senior medical clinicians and it is hard to imagine how other professional groups would have either the autonomy of day-to-day practice or the political clout. Despite this, they argue that what is needed in teams is a group of professionals with a set of competencies that range from acute through to rehabilitation care and that leadership may not necessarily be best performed by the doctors in all phases. The primacy of the doctor’s skills, like those of the physiotherapist or social worker, vary according to where the patient or client is on the continuum of care. Interestingly, the Australian Cancer Network and National Breast Cancer Centre in its clinical guidelines (2003) notes that ‘any member of the multidisciplinary team may, with the woman’s approval, become the lead person for ongoing communication about her care’ (Moorin 2005:30). The distinction between structural team leadership and (shared) clinical leadership in the care of individual patients and families is a useful one.

Individual qualities as enablers to MTC

At the individual level team members need a high level of professional and self-knowledge, and skills and attitudes that enable them to develop a shared understanding of the tasks to be performed by all involved. This includes a clear idea of each other’s role, skills and knowledge and a capacity to anticipate the needs of other members of the team (Baker et al 2006, Mickan & Rodger 2000) in order to meet the individual needs of clients (Liberman et al 2001). Baker and colleagues also identify an ability to adjust to team decisions, along with a capacity to use the range of communication mediums in place whether this be case notes, emails, telemedicine or face-to-face interactions. They also cite mutual trust as a key quality for effective teamwork as does Bronstein (2003).

Box 6.8

The four case study participants suggested that leadership in the team ebbed and flowed according to the task to be done. At times different members of the team took the lead, although this shift in leadership did not necessarily impact on team structure, since there needed to be a constant team manager. Among the physicians, one took the primary role as the point of coordination and communication with families. Leadership tensions were avoided by all members of the team having clear ideas about the roles and skills of each team member which in turn engendered respect. There were some individuals who found the team model difficult, and they sometimes left the team. Others needed support and coaching to relinquish ‘solo operator’ models of work, which had previously been expected and rewarded. An important factor in the success of the team was strong support and an expectation from management at all levels that MTC was the process of care.

Professional jealousies can be a major issue for effective teamwork and patients readily pick up these tensions. In the interviews R reflected upon the frustration felt by nurses at the power of doctors to make medical decisions, while J mused on the opportunities afforded to nurses to develop a deep and trusting relationship with the client who gave them insights into the patient not enjoyed by the doctor. These inter-professional tensions spill over into practice blurring the boundaries especially for young doctors in training who look to the consultant for leadership and decision making, while experienced nurses espouse a model of shared care arrived at through discussion at weekly team meetings.

Box 6.9

Additional barriers were identified by the case study participants. For them the rapid turnover of patients in the acute sector worked against MTC leading them to reinforce the idea that this approach to clinical work was best achieved in long-term care of chronic conditions – in the acute setting, at best, the team was the doctor and the nurse. Coupled with this they argued that work intensification meant more pressure on staff to get the work done and the patients through the system. Spending time on meetings was viewed as not cost effective. They also noted that the move to autonomous practice – especially in community health – worked against teamwork. In the community, teams may be multidisciplinary in composition, but often operate as autonomous practitioners, rarely meeting each other face to face.

Conclusion

This chapter has used a case study and narrative interwoven with the literature to explore the definition of multidisciplinary care, its effectiveness, barriers and facilitators. It has explored the implications of the client being seen as a member of this team, although like other team members their position is not constant. They may opt in or out depending on their capacity to engage in the processes and, importantly, on their capacity to grasp the implications of the knowledge underpinning clinical decision making. In the case study Keown’s mother represents the extreme on the continuum of an informed family member. This continuum extends from other clients like her, trained health professionals with a capacity to do their own research on the evidence, to those with little knowledge of diagnosis or the various treatment modalities, or limited ability to assertively make their needs known. Some clients may make decisions to seek or refuse treatment that the team sees as dangerous. Knowledge of the diagnosis, treatments available and the implications mean clients and their families will be differently positioned within the team, and make demands on other team members in different ways. Clients with little knowledge will require more time for education and information; others will need time to deal with the complexity of decision making. Families and patients also differ from other members of the team in attachment to the outcomes. They are not health professionals seeking to provide value-neutral care for their client in a spirit of all that is positive in professional detachment. For families and clients their emotional attachment is, as it should be, self-centred.

The case study focuses on client-centred MTC in paediatric oncology. In the accounts provided by the four participants the MTC was most active during the outpatient treatment and palliative stages. We have already noted that MTC seems to be more prevalent where the patient or client has a chronic condition, where cure is not the major goal. At this point MTC can offer a wide range of care incorporating symptom management, family support, coordination of community services, and counselling. Of course there are other areas of healthcare that espouse client-centred MTC, including aged care and rehabilitation. In these areas, clients are often able to engage in the team process, understand the goals set for their care and report back to team members on the efficacy of interventions. These long-term relationships with adult clients are well suited to patient and family-centred MTC. What is needed to further client-centred MTC is rigorous research of a qualitative nature that investigates the impact of teamwork on diagnosis and treatment, and quantitative studies that evaluate the clinical and financial gains to be made by taking a team approach. A distillation of the ‘take home messages’ we garnered from our reading, discussion and writing of this chapter, and a final word on Keown, are provided in Boxes 6.10 and 6.11

Box 6.10

The following principles are offered as a guide to health professionals in establishing MTC or extending its practice.

Structural: MTC depends on some enduring team structures along with the coming together of shorter term teams to meet the needs of particular patients or situations. Team structures need to be supported with good policy and systems. More innovation and experimentation is needed, as well as a stronger evidence base.

Financial: Remuneration in support of clinicians (particularly those funded on fee-for-service) engaging in teamwork is needed. The costs of setting up MTC are real, but so are the benefits (potentially including reduced utilisation of some interventions), and mature teams can develop efficient teamwork practices.

Systems: Managers and senior clinicians can enhance MTC through financial and human resource support for the smooth functioning of the team. Information systems can make teamwork easier.

Process: Effective MTC requires a commitment to regular meetings, and resources for implementing team decisions. Strong leadership is required for day-to-day management of enduring teams, but flexibility is needed to allow the most appropriate member to take leadership for particular patients or kinds of team tasks.

Respect: Teams need to operate from a basis of deep respect and understanding for each other’s roles, and clear shared ideas of each member’s roles and responsibilities. This has implications for formative and continuing education. There also needs to be a recognition that not all professionals are effective team players.

Individual professionals: Members of teams need to be confident in their own discipline boundaries, and comfortable to make suggestions in support of the client’s care. This includes the ability to provide patients with treatment options and risks, and facilitate patient decision making, along with a capacity to be flexible in the face of decisions made by patients or other members of the team.

Patients and their families: The shared goal of meeting patient needs underlies the methods of MTC. Patients and families benefit from confidence that the care they receive is provided by a responsible team that they can rely on. They need to be factored into planning and decision making, and time is required to acquaint them of options, benefits and risks, and respect their choices about the extent of their engagement in decision making and caregiving.

Box 6.11

Sandra: Keown didn’t live to see his 10th birthday. I received the call from our oncologist one morning. Doctor: ‘Ah, hello. We have the report from the MRI. It’s not looking good. The tumour has spread. It’s all through the ventricles … I can’t be sure, but there could be a bit in the base of the spinal cord …’

Keown lived his final 18 months of life with all his heart and all his soul. We visited Movie World. He rode his scooter – preferably very fast down hill and around corners – until he could no longer walk. He knew he was dying. ‘I don’t want to die, but when I do I want you to remember me as brave and strong and smart.’

And when we celebrated his life, at his final ‘goodbye for now’ party, his oncologist, his nurses, his GP, his palliative care nurse practitioner, his friends, his school mates, his family and his neighbours – we were all there, all part of the team, all there to send Keown on his way.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the contributions of Ms Sara Fleming, Dr Michael Rice and Ms Michelle Todd whose experience and perspectives informed this chapter. Our thanks also to Anne Cahill Lambert for her assistance in developing the literature review for this article.

References

Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Healthcare (ACSQHC), Safety and quality council action plan 2001. (2000) Australian Government, Canberra.

Bronstein, L., A model for interdisciplinary collaboration, Social Work Research 48 (3) (2003) 297–306.

Burns, T.; Lloyd, H., Is a team approach based on staff meetings cost effective in the delivery of mental healthcare?Current Opinion in Psychiatry 17 (4) (2004) 311–314.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF), Teamwork in healthcare: promoting effective teamwork in healthcare in Canada: policy synthesis and recommendations. (2006) CHSR, Ottawa.

Children’s Hospital at Westmead, A Handbook for families. (2005) CHM, Sydney.

Cohen, S.G.; Bailey, D.R., What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite, Journal of Management 23 (4) (1997) 238–290.

Edmondson, A.C.; Bohmer, R.M.; Pisano, G.P., Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals, Administrative Science Quarterly 46 (2001) 685–716.

Ettner, S.L.; Kotlerman, J.; Afifi, A.; et al., An alternative approach to reducing the costs of patient care? A controlled trial of the multi-disciplinary doctor-nurse practitioner (MDNP) model, Medical Decision Making 26 (1) (2006) 9–17.

Fleissig, A.; Jenkins, V.; Catt, S.; et al., Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK?Lancet Oncology 11 (2006) 935–943.

Frost, M.; Arvizu, R.; Jayakumar, S.; et al., Multidisciplinary healthcare delivery model for women with breast cancer: patient satisfaction and physical and psychosocial adjustment, Oncology Nursing Forum 26 (10) (1999) 1673–1680.

Gabel, M.; Hilton, N.; Nathanson, S., Multidisciplinary breast cancer clinics: do they work?Cancer 79 (12) (1997) 2380–2384.

Grumbach, K.; Bodenheimer, T., Can healthcare teams improve primary care practice?JAMA 291 (2004) 1246–1251.

Haward, R.; Amir, Z.; Borrill, C.; et al., Breast cancer teams: the impact of constitution, new cancer workload, and methods of operation on their effectiveness, British Journal of Cancer 89 (1) (2003) 15–22.

Herrman, H.; Trauer, T.; Warnock, J., The roles and relationships of psychiatrists and other service providers in mental health services, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 36 (1) (2002) 75–80.

Howard, G.; Thomson, C.; Stroner, P.; et al., Patterns of referral, management and survival of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer in Scotland during 1988 and 1993: results of a national retrospective population-based audit, British Journal of Urology 87 (4) (2001) 339–347.

Lebrasseur, R.; Whissell, R.; Ojha, A., Organisational Learning, Transformational Leadership and Implementation of Continuous Quality Improvement in Canadian Hospitals, Australian Journal of Management 27 (2) (2002) 141–162.

Leggat, S., Effective healthcare teams require effective team members: defining teamwork competencies, BMC Health Services Research 7 (17) (2007); doi:10.1186/1472–6963–7–17.

Liberman, R.P.; Hilty, D.M.; Drake, R.; et al., Requirements for multidisciplinary teamwork in psychiatric rehabilitation, Psychiatric Service 52 (10) (2001) 1331–1342.

Mathews, J., From Post-Industrialism to post-fordism, Meanjin 48 (1) (1989) 139–152.

Mathews, J., Ford Australia plastics plant: Transition to teamwork through quality enhancement, UNSW Studies No 3. (1991) University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Mickan, S.; Rodger, S., Characteristics of effective teams: a literature review, Australian Health Review 23 (3) (2000) 201–208.

Moorin, R., Inquiry into Service and Treatment Options for People with Cancer: briefing paper: Multidisciplinary Care, Centre for Health Services Research. (2005) School of Population Health, University of Western Australia, Perth.

Morris, R., The Age of workplace reform in Australia, In: (Editors: Mortimer, D.; Leece, P.; Morris, R.) Workplace reform and enterprise bargaining (1996) Harcourt Brace, Sydney.

Parker-Oliver, D.; Bronstein, L.; Kurzejeski, L., Examining variables related to successful collaboration on the hospice team, Health & Social Work 30 (4) (2005) 279–286.

Sainsbury, R.; Haward, B.; Rider, L.; et al., Influence of clinician workload and patterns of treatment on survival from breast cancer, The Lancet 34 (1995) 1265–1270.

Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee, The cancer journey: Informing choice, Report on the inquiry into services and treatment options for persons with cancer. (2005) Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Sutcliffe, P.; Callus, R., Glossary of Australian Industrial Relations terms. (1994) ACIRRT & ACSM. University of Sydney, Sydney.

West, M.; Borrill, C.; Dawson, J.; et al., The link between the management of employees and patient mortality in acute hospitals, International Journal of Human Resource Management 13 (8) (2002) 1299–1310.

Wilson, D.; Moores, D.; Woodhead Lyones, S.; et al., Family Physicians’ interest and involvement in interdisciplinary collaborative practice in Alberta, Canada Primary Healthcare Research and Development 6 (2005) 224–231.