Chapter 25

The Clinical Record

May I never forget that the patient is a fellow human creature in pain. May I never consider the patient merely a vessel of disease.

From Oath of Maimonides (1135–1204)

Putting the History and Physical Examination Together

Until this point, this book has dealt separately with the history and the physical examination. Chapters 1 to 3 give an in-depth analysis of history-taking techniques. Chapters 4 to 18 discuss the many elements of the physical examination, and Chapter 19 suggests an approach to performing the complete physical examination and its write-up. Chapters 20 to 23 cover the evaluation of specific patients. Chapter 24 discusses data gathering and data analysis. This chapter suggests how the history and the physical examination can be integrated into one succinct statement about the patient.

In writing up the history and the physical examination, the examiner should follow several rules:

The patient’s medical record is a legal document. Comments regarding the patient’s behavior and attitudes should not be part of the record unless they are important from a medical or scientific standpoint. Describe all parts of the examination that you performed and indicate those that you did not perform. A statement such as “the examination of the eye is normal” is much less accurate than “the fundus is normal.” In the first case, it is not clear whether the examiner actually attempted to look at the fundus. If a part of the examination was not performed, state that it was “deferred” for whatever reason. Finally, it is not necessary to state all the possible abnormalities if they are not present. It is acceptable to state that “the pharynx was normal” instead of “the pharynx was not injected, and there was no evidence of discharge, erosion, masses, or other lesions.” It is clear from the first statement that the examiner inspected the pharynx and believed that it was normal.

Now consider again the patient Mr. John Doe, whose interview was recorded in Chapter 3, Putting the History Together. The following text describes the complete history and physical examination of this patient.

Patient: John Doe

Date: July 19, 2013

History

Source

Self, reliable.

Chief Complaint

“Chest pain for the past 6 months.”

History of Present Illness

This is the first St. Catherine’s Hospital admission for this 42-year-old lawyer with atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. The patient’s history of chest pain began 4 years before admission. He described the pain as a “dull ache” in the retrosternal area, with radiation to his left arm. The pain was provoked by exertion and emotions. On July 15, 2012, Mr. Doe suffered his first heart attack while playing tennis. He had an uneventful hospitalization in Kings Hospital in New York City. After 3 weeks in the hospital and 3 weeks at home, he returned to work. The patient suffered a second heart attack 6 months later (January 9, 2013), again while playing tennis. The patient was hospitalized in Kings Hospital, during which time he was told of an “irregularity” in his heart rate. Since then, the patient has not experienced any palpitations, nor has he been told of any further irregularities.

Over the past 6 months, Mr. Doe has noted an increase in the frequency of his chest pain. The pain now occurs 4 to 5 times a day and is relieved within 5 minutes with 1 or 2 nitroglycerin tablets under his tongue. The pain is produced by exercise, emotions, and sexual intercourse. The patient also describes 1-block dyspnea on exertion. The patient relates that 6 months ago, he could walk 2 or 3 blocks before becoming short of breath.

Although the patient shows significant denial of his illness, he is anxious and depressed.

The patient has currently been admitted for elective cardiac catheterization.

Past Medical History

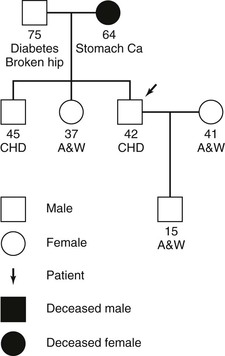

Family History (Figure 25-1)

Father, 75, diabetes, broken hip

Mother died, 64, stomach cancer

Figure 25–1 Family tree of patient John Doe. A&W, Alive and well; Ca, cancer; CHD, coronary heart disease.

There is no family history of congenital disease. No other history of diabetes or cardiac disease. No history of renal, hepatic, or neurologic disease. No history of mental illness.

Psychosocial History

“Type A” personality; born and raised in Middletown, New York; family moved to Rochester, New York, when Mr. Doe was 13 years of age; patient moved to New York City after high school; college and law school in New York City; he is now a senior partner of a law firm for which he has worked for the past 17 years; married to Emily for the past 13 years; was an active tennis player before second heart attack; before 6 months ago, enjoyed the theater and reading.

Sexual, Reproductive, and Gynecologic History

Patient is male, exclusively heterosexual, with one partner, his wife. He has one son, age 15 years. Recently, because of angina, the patient has stopped having sexual relations. He has noted that for the past 2 years his erections have been “less hard.”

Review of Systems

General: Depressed for the past 6 months as a result of his ill health.

Skin: No rashes or other changes.

Head: No history of head injury.

Ears: Patient not aware of any problem hearing; no dizziness, discharge, or pain present.

Neck: No masses or tenderness.

Breasts: No masses or nipple discharge noted.

Cardiac: As noted in History of Present Illness.

Vascular: No history of cerebrovascular accidents or claudication.

Musculoskeletal: No joint or bone symptoms; no weakness; no history of back problems or gout.

Physical Examination

Head: Normocephalic, without signs of trauma.

Sinuses: No tenderness present over frontal or maxillary sinuses.

Mouth and throat: Lips pink; buccal mucosa pink; all teeth in good condition, without obvious caries; gingivae normal, without bleeding; tongue midline and without masses; uvula elevates in midline; gag reflex intact; posterior pharynx normal.

Breasts: Normal male, without masses, gynecomastia, or discharge.

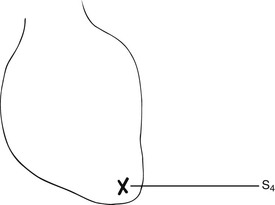

Heart: Point of maximum impulse (PMI), fifth intercostal space, midclavicular line (5ICS-MCL); S1 and S2 normal; normal physiologic splitting present; a loud S4 is present at the cardiac apex; no murmurs or rubs are heard (Figure 25-2).

Lymphatic: No adenopathy noted.

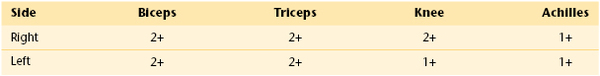

Neurologic: Oriented to person, place, and time; cranial nerves II to XII intact (cranial nerve I not tested); gross sensory and motor function normal; cerebellar function normal; plantar reflexes down; gait normal; deep tendon reflexes as in Table 25-1.

Summary

Mr. Doe is a “type A” 42-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (status post [S/P]1 two myocardial infarctions: July 2012 and January 2013), whose current admission is for elective cardiac catheterization. His risk factors for coronary artery disease are untreated hypertension and a long history of cigarette smoking. The patient has a brother who suffered a myocardial infarction at the age of 40 years.

Physical examination reveals a slightly obese man with hypertension and its associated early to intermediate funduscopic changes. Cardiac examination reveals a loud fourth heart sound, suggestive of a noncompliant (stiff) ventricle. This may be a manifestation of ischemic heart disease or ventricular hypertrophy secondary to the hypertension. Although the patient is not aware of any lipid abnormalities, numerous tendinous xanthomata on the hands are present, which are strongly suggestive of hypercholesterolemia, an additional risk factor for premature coronary artery disease.

The problem list containing all Mr. Doe’s health problems, identified with their dates of recognition and resolution, might look like Table 25-2. This list is used each time the patient is seen and examined. For each problem, the clinician should develop a strategy for its ultimate resolution. Each problem should have the following four components:

Table 25–2

Problem List for Patient John Doe

| Problem | Date | Resolved |

| 1. Chest pain | 2008 | |

| 2. Myocardial infarction | July 15, 2012 | 3 weeks later |

| 3. Myocardial infarction | January 9, 2013 | 6 weeks later |

| 4. Hypertension | Years | |

| 5. Smoking | 1992 | July 15, 2012 |

| 6. Tendinous xanthomata | ? | |

| 7. S4 gallop | ||

| 8. Dyspnea on exertion | 6 months ago | |

| 9. Depression | 3 months ago | |

| 10. Weight loss | 3 months ago | |

| 11. Sleeping abnormality | 3 months ago | |

| 12. Diet modification | 3 months ago | |

| 13. Appendectomy | 1986 |

This is the SOAP format (Weed, 1968), which contains an update of the subjective and objective data, as well as the assessment of the problem and the plan for its resolution. The heading of the progress note should include the date, the time, the name of the person who is writing the note, and the service the patient is using. It is very helpful to list the antibiotics and the day of the course of antibiotics at the top of the progress note, as well as other medications and doses. If the patient has undergone surgery, indicate postoperative time on the top as well (e.g., “Postop Day 3”).

Subjective information is what patients tell you. How are they feeling? What are their symptoms? What are they eating? If their food status is nothing by mouth (NPO), note it here. How are they sleeping? How are they ambulating, urinating, defecating, and so forth?

Objective information is what you gather from your physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiographic studies. Always include the vital signs and total fluid input and output over the last shift if the patient is NPO or on a diuretic regimen. If daily weights are being recorded, they should be included here as well. Your physical examination write-up should include only pertinent positive and negative findings and any changes.

The assessment is your impression of the patient’s problem or level of progress; it is a summary of how the patient is doing and what has changed from the previous day.

The plan is what you are going to do about each problem. It may include continuing, starting, or discontinuing a medication, laboratory tests to order, test results to obtain, consults to be called, and individual or family education.

The SOAP note is not supposed to be as complete as an admit note. Complete sentences are not necessary, and abbreviations are common. Remember that abbreviations, however, can differ for each specialty! PND generally is an abbreviation for paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea for most medical services, but for an ear, nose, and throat service, PND is an abbreviation for postnasal drip. MS is commonly used for multiple sclerosis, but to a cardiologist, MS is mitral stenosis; to a pharmacist or anesthesiologist, MS is morphine sulfate; to an orthopedist or rheumatologist, MS is musculoskeletal.

The length of the note differs for each specialty as well. In general, medical notes tend to be long and surgical notes are short, but you will have to get a sense of what to do from the house staff team. Typically, medical students’ notes are more detailed than the house staff note.

Always remember that the chart is a legal document. You should be confident in your presentations, but be conservative in the chart and present the facts clearly. Do not discuss other clinicians’ opinions. Let the facts in the chart speak for themselves.

The Human Dimension

The practice of medicine is an extraordinary profession. The thrill of interviewing and examining your first patient should always stay in your mind. Clinicians must remember that even during the most trying times, they have been granted the enormous responsibility of caring for a patient. Common courtesy, kindness, respect, and attentiveness to the patient go a long way in establishing the so-called bedside manner, which has become less evident in the past few decades. Imagine yourself in the patient’s situation. How would you like to be treated? Each student in medical school has the potential to develop into a devoted and compassionate clinician.

Always strive for precision and accuracy. Be strict in your approach to the history and physical examination. Always follow the same basic routines. Do not take shortcuts. It takes time to develop the skills of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Only with experience can the clinician master physical diagnosis.

This textbook is only the introduction to a lifetime of learning about patients and their problems and diseases. As students, you will learn much from your patients. Even seasoned diagnosticians learn daily from their patients. Just as no two individuals have the same face or body appearance, no two individuals will react the same way to the same disease. This is one of the most exciting things about medicine: Every day offers new patients, new problems, new solutions.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Cameron S, Turtle-Song I. Learning to write case notes using the SOAP format. J Couns Dev. 2002;80:286.

Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:593.

Weed LL. The problem oriented record as a basic tool in medical education, patient care, and research. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:131.

1 S/P is an abbreviation for “status post,” referring to a state that follows a medical intervention or a medical condition.