Advances in Anesthesia, Vol. 28, No. 1, ** **

ISSN: 0737-6146

doi: 10.1016/j.aan.2010.07.003

Measuring the Clinical Competence of Anesthesiologists

The problem in perspective

Why is so much attention directed at judging physician competence in the United States? Much of this attention has been thrust on health care practitioners by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM was chartered in the United States in 1970 by the National Academy of Sciences. According to the Academy’s 1863 charter, its charge is to enlist distinguished members of the appropriate professions in the examination of policy matters pertaining to public health and to act as an adviser to the federal government on issues of medical care, research, and education. In 1998, the Quality of Health Care in America Project was initiated by the IOM with the goal of developing strategies that would result in a threshold improvement in quality in the subsequent 10 years [1].

Toward that goal, the Quality of Health Care in America Project published a series of reports on health care quality in the United States. The first in the series was entitled To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. This report on patient safety addressed a serious issue affecting the quality of our health care, specifically human error. This first report began by quoting 2 large US studies, one conducted in Colorado and Utah and the other in New York, which found that adverse events occurred in 2.9% and 3.7% of hospitalizations, respectively. In the Colorado and Utah hospitals, 8.8% of adverse events led to death, compared with 13.6% in New York hospitals. In both of these studies, more than half of these adverse events resulted from medical errors and, according to the IOM, could have been prevented [1].

When extrapolated to the more than 33.6 million hospital admissions in the United States during 1997, the results of these studies implied that 44,000 to 98,000 Americans avoidably die each year as a result of medical errors. Even when using the lower estimate, death caused by medical errors becomes the eighth leading cause of death in the United States. More people die in a given year as a result of medical errors than from motor vehicle accidents (43,458), breast cancer (42,297), or AIDS (16,516). The IOM estimated the costs of preventable adverse events, including lost income, lost household production, disability, and health care costs, to be between 17 and 29 billion dollars annually; health care expenditures constitute more than half of these costs [1].

The IOM did attempt to do more than point out the problems. As mentioned earlier, the goal of the Quality of Health Care in America Project was to develop strategies to substantially improve health care quality in a 10-year period. The strategies recommended by the IOM fell into a 4-tiered framework as follows:

The IOM believed that the delivery level would be the ultimate target of all their recommendations. By way of example, anesthesiology was cited as an area in which impressive improvements in safety had been made at the delivery level. The initial report of the Quality of Health Care in America Project stated, “As more and more attention has been focused on understanding the factors that contribute to error and on the design of safer systems, preventable mishaps have declined. Studies, some conducted in Australia, the United Kingdom and other countries, indicate that anesthesia mortality is about 1 death per 200,000 to 300,000 anesthetics administered, compared with 2 deaths per 10,000 anesthetics in the early 1980s [1].” The reference cited for this marked improvement in anesthesia-related mortality does not describe the study that resulted in the lower rate quoted by the IOM and does not have an author listed [2]. Some believe that the IOM’s claim of improved anesthesia mortality resulted from a study by John Eichhorn, who examined 11 cases of major intraoperative accidents that had been reported to a malpractice insurance carrier between 1976 and 1988 [3]. In an effort to remove disease and postoperative care as contributing factors, Eichhorn’s study considered only patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status of I or II who died intraoperatively. Therefore, 5 intraoperative anesthesia-related deaths out of an insured population of 1,001,000 ASA Physical Status I or II patients resulted in a mortality of 1 per 200,200 in which anesthesia was considered the sole contributor [4]. In a 2002 review of the published literature, anesthesia-related mortality in less exclusive general patient populations ranged from 1 in 1388 anesthetics to 1 in 85,708 anesthetics, and preventable anesthetic mortality ranged from 1 in 1707 anesthetics to 1 in 48,748 anesthetics. When anesthesia-related death is defined as a perioperative death to which human error on the part of the anesthesia provider has contributed, as determined by peer review, then anesthesia-related mortality is estimated to be approximately 1 death per 13,000 anesthetics [3].

As noted in the corrective strategies listed earlier, error reporting and peer review were among the recommendations of the IOM report. It was believed that a nationwide, mandatory public-reporting system should be established for the collection of standardized information about adverse events that result in death or serious patient harm. Despite this aggressive approach, the Quality of Health Care in America Project also saw a role for voluntary, confidential reporting systems. Their initial report recommended that voluntary reporting systems be encouraged to examine the less severe adverse events and that these reports be protected from legal discoverability. In this model, information about the most serious adverse events that result in harm to patients, and which are subsequently found by peer review to result from human errors, would not be protected from public disclosure. For less severe events, public disclosure was not recommended by the IOM because of concerns that fear about legal discoverability of information might undermine efforts to analyze errors to improve safety [1].

In the second report from the Quality of Health Care in America Project, the IOM described the gap between our current health care system and an optimal health care system as a “quality chasm.” They went on to say that efforts to close this gap should include analysis and synthesis of the medical evidence, establishment of goals for improvement in care processes and outcomes, and development of measures for assessing quality of care. This second report also emphasized the importance of aligning payment policies with quality improvement, and changing the ways in which health professionals are regulated and accredited [5].

This article examines the quality chasm as it applies to anesthesiologists, and current efforts to close the gap. The current methods of judging clinical competence, such as licensure and certification, in contrast to the evolving Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) outcomes project and the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA) Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA), are investigated. The traditional role of peer review in judging clinical competence and its importance in affecting changes in physician behavior are delineated. The article also takes a critical look at the ability of existing national database registries, such as the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), to judge clinical competence, and compares this with the mission and vision of the emerging Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI). The taboo areas of judging clinical competence for the aging anesthesiologist and those returning to the work force after recovery from substance abuse disorders are also examined.

Licensure and certification

The 10th Amendment of the United States Constitution authorizes states, and other licensing jurisdictions, such as United States territories and the District of Columbia, to establish laws and regulations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of their citizens. Medicine is a regulated profession because of the potential harm to the public if an incompetent or impaired physician is allowed to practice. To protect the public from incompetent or impaired physicians, state medical boards license physicians, investigate complaints, discipline those who violate the law, conduct physician evaluations, and facilitate rehabilitation of physicians where appropriate. There are currently 70 state medical boards authorized to regulate allopathic and osteopathic physicians.

Obtaining an initial license to practice medicine in the United States is a rigorous process. State medical boards universally ensure that physicians seeking licensure have met predetermined qualifications that include graduation from an approved medical school, postgraduate training of 1 to 3 years, background checks of professional behavior with verification by personal references, and passage of a national medical licensing examination. All states currently require applicants to pass the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), or past equivalent. Passing the USMLE is a 3-step process. Step 1 assesses whether the applicant understands and can apply the basic sciences to the practice of medicine, including scientific principles required for maintenance of competence through lifelong learning. This assessment is in the form of an examination made up of multiple-choice questions with one best answer. Step 2 assesses the clinical knowledge and skills essential for the provision of safe and competent patient care under supervision. The clinical knowledge assessment is also in the form of an examination made up of multiple-choice questions, but the clinical skills assessment uses standardized patient models to test an applicant’s ability to gather information from patients, perform physical examinations, and communicate their findings to patients and colleagues. Step 3 assesses whether an applicant can apply medical knowledge and understanding of biomedical and clinical science in the unsupervised practice of medicine, with emphasis on patient management in ambulatory settings. This part of the USMLE also takes the form of an examination made up of multiple-choice questions. Although initial medical licensure relies heavily on examinations composed of multiple-choice questions, most agree that it is a moderately rigorous process with sufficient state oversight to assure initial physician competence and to provide a measure of valuable public protection [6].

Although the achievement of licensure to practice medicine is generally accepted as adequate assurance of initial competence, the processes in place for assessment of continuing competence have raised increasing concern among medical professionals, licensing authorities, and other interested parties, including the general public. After physicians are initially licensed, they must renew their license to practice medicine every 2 to 3 years to continue their active status. During this renewal process, physicians must show that they have maintained acceptable standards of professional conduct and medical practice as shown by a review of the NPDB, the Federation Physician Data Center, and other sources of public information held by the states. In most states, physicians must also show they have participated in a program of continuing medical education and are in good health. These criteria are often satisfied by a declaration by the physician that he or she has completed approximately 40 hours of continuing medical education over the past 2 years, and has continued in the active practice of medicine with no known physical or mental impediments to that practice. The renewal process does not involve an examination of knowledge, practical demonstration of competence, or peer review of practice [7].

Peer review

In 1986, Governor Mario Cuomo of New York State announced his plan to have physician credentials periodically recertified as part of the renewal process for medical licensure. He convened the New York State Advisory Committee on Physician Recredentialing, which subsequently recommended physicians be given 3 options for satisfying the requirements of relicensure. These options included: (1) specialty board certification and recertification, (2) examination of knowledge and problem-solving ability, and (3) peer review in accord with standardized protocols. In 1989, the New York State Society of Anesthesiologists (NYSSA) began developing a model program of quality assurance and peer review to meet the evolving requirements for the recredentialing and relicensure of anesthesiologists in New York State. In that same year, the ASA endorsed a peer review model, developed by Vitez [8,9], which created error profiles for comparison of practitioners. The NYSSA modified this model for the purpose of recredentialing and relicensure of anesthesiologists with the belief that standardized peer review was the only appropriate method for identifying patterns of human error in anesthesiologists [10]. The NYSSA hoped that a standardized peer review model would permit development of a statewide clinical profile containing the performance of all anesthesiologists practicing in the state. Conventional statistical methods would then be used to compare the clinical profiles of individual anesthesiologists with the statewide profile to identify outliers who may need remediation.

The NYSSA model program was never instituted in New York State because the recommendations of the New York State Advisory Committee on Physician Recredentialing were never enacted into New York public health law. Many statewide professional review boards, and the NPDB, track deviations from accepted standards of care, but lack individual denominator data to determine error rates. Therefore, the concept of identifying clinical outliers among anesthesiologists by error profiles has never been tested and may not be feasible. Individual denominator data are available to departments of anesthesiology in the form of administrative billing data and, when combined with a structured peer review model, can produce individual rates of human error. However, it is unlikely that the number of patients treated by an anesthesiologist offers enough statistical power to use rate of human error as a feasible means of judging clinical competence.

In a recent study of 323,879 anesthetics administered at a university practice using a structured peer review of adverse events, 104 of these adverse events were attributed to human error for a rate of 3.2 per 10,000 anesthetics. With this knowledge, faculty of this university practice were asked what rate of human error by an anesthesiologist would indicate the need for remedial training, and suggest incompetence. The median human error rates believed to indicate the need for remedial training and suggest incompetence were 10 and 12.5 per 10,000 anesthetics, respectively. Power analysis tells us that, if we were willing to be wrong about 1 out of 100 anesthesiologists judged to be incompetent (alpha error of 0.01) and 1 out 20 anesthesiologists judged to be competent (beta error of 0.05), then sample sizes of 21,600 anesthetics per anesthesiologist would be required [11]. Even at these unacceptably high levels of alpha and beta error, an appropriate sample size could require more than 2 decades to collect. Therefore, the concept of using human error rates to judge clinical competence is not feasible and this has implications for all database registries designed for this purpose.

Closed claims and the NPDB

The Health Care Quality Improvement Act of 1986 led to the establishment of the NPDB, an information clearinghouse designed to collect and release certain information related to the professional competence and conduct of physicians. The establishment of the NPDB was believed to be an important step by the US Government to enhance professional review efforts by making certain information concerning medical malpractice payments and adverse actions publicly available. As noted earlier, the NPDB lacks the denominator data necessary to determine individual provider error rates to judge clinical competence. Even if individual denominator data were available, malpractice closed claims data are also likely to lack the statistical power necessary to be a feasible measure of clinical competence. For example, in a study of 37,924 anesthetics performed at a university health care network between 1992 and 1994, 18 cases involved legal action directed at an anesthesia provider. An anesthesiologist was the sole defendant named in 2 malpractice claims, only one of which resulted in a $60,000 award. A single letter of intent also named an anesthesiologist as the sole defendant. In the 15 additional legal actions, an anesthesia provider was named as codefendant in 3 claims and implicated in 12 letters of intent. The incidence of all legal actions against the anesthesia practitioners in this sample was 4.7 per 10,000 anesthetics, and the single judgment against a practitioner in this sample represents a closed claims incidence of 0.26 per 10,000 anesthetics [12].

More importantly, there may be no relationship between malpractice litigation and human errors by anesthesiologists. In the sample that yielded 18 cases involving legal action, there were a total of 229 adverse events that resulted in disabling patient injuries. Of these 229 disabling patient injuries, 13 were considered by peer review to have resulted from human error, or deviations from the standard of care, on the part of the anesthesia provider. The rate of anesthetist error leading to disabling patient injuries, therefore, was 3.4 per 10,000 anesthetics. Comparison of legal action and deviations from the standard of care showed the 2 groups to be statistically unrelated. None of the 13 cases in which a disabling injury was caused by deviations from the standard of care, as determined by peer review, resulted in legal action; and none of the 18 cases involving legal action was believed to be due to human error on the part of the anesthesia provider. Therefore, closed malpractice claims lack both statistical power and face validity as a measure of competence [12].

Indicators of clinical competence and face validity

Malpractice claims are not the only indicator of clinical competence that may lack validity. The first anesthesia clinical indicators developed in the United States came from the Joint Commission (TJC), formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. These original 13 anesthesia clinical indicators (Box 1) were adverse perioperative events that were intended to trigger a peer review process to assess the contribution of anesthesia care. Before the release of these indicators in 1992, TJC conducted alpha testing for face validity and ease of data collection in a limited number of health care facilities. After their initial release, these indicators were subjected to beta testing, in which similar characteristics were evaluated in a broader range of health care organizations. Following the completion of the beta phase in 1993, the original 13 anesthesia clinical indicators were reduced by TJC to 5 perioperative performance indicators in an effort to make them applicable to a broader range of institutions and to emphasize that these adverse outcomes are not specific to errors in anesthesia care.

Box 1 Anesthesia clinical indicators drafted in 1992 by TJCa

a The original 13 anesthesia clinical indicators developed in the United States by TJC were reduced to 5 perioperative performance indicators* after testing for face validity and feasibility of data collection.

Similarly, a recent systematic review by Haller and colleagues [13] identified 108 clinical indicators related to anesthesia care, and nearly half of these measures were affected by some surgical or postoperative ward care. Using the definitions of Donabedian [14], 42% of these indicators were process measures, 57% were outcome measures, and 1% related to structure. All were felt to have some face validity, but validity assessment relied solely on expert opinion 60% of the time. Perhaps more disconcerting, the investigators found that only 38% of proscriptive process measures were based on large randomized control trials or systematic reviews [13].

Metric attributes

Although showing the validity of performance measures should be necessary for judging clinical competence, it may not be sufficient when these performance measures are intended to influence physician reimbursement for patient care. In 2005, a group of 250 physicians and medical managers from across the United States convened a conference to produce a consensus statement on how “outcomes-based compensation arrangements should be developed to align health care toward evidence-based medicine, affordability and public accountability for how resources are used.” This consensus statement recommended several important attributes for measures included in pay-for-performance (P4P), or value-based compensation, programs. These attributes included high volume, high gravity, strong evidence basis, a gap between current and ideal practice, and good prospects for quality improvement, in addition to the already discussed reliability, validity, and feasibility [15]. A high-volume measure examines frequently experienced processes and outcomes of care, or common structural attributes, whereas high gravity implies that there is a large potential effect on health associated with the metric. Although most agree that there should be evidence of linkage between a change in a measure and its related outcomes, it must be accepted that this linkage can be dynamic. Take, for example, the changing evidence linkage between the use of perioperative β-blockers and its effect on perioperative cardiac events in certain patient populations. Therefore, performance measure must be maintained in a manner similar to practice guidelines with periodic assessments of the evidence and gap. As the gap between current and ideal practice closes, P4P measures are likely to be retired by payers [15].

Guiding principles for the management of performance measures

In 1997, the ASA established the Ad Hoc Committee on Performance Based Credentialing, which created Guidelines for Delineation of Clinical Privileges. These guidelines suggest that performance measures, compared with benchmarks, should be considered in the delineation of clinical privileges in anesthesiology. Because national benchmarks did not exist, the Ad Hoc Committee on Performance Based Credentialing became the standing Committee on Performance and Outcome Measures (CPOM), in 2001. The first order of business for CPOM was to develop Guidelines for (Performance & Outcomes) Database Management by the American Society of Anesthesiologists that has evolved into Guiding Principles for the Management of Performance Measures by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. This document, last modified in 2005, describes the development and maintenance of clinical indicators (clinical outcomes, processes of care, and perceptions of care) and administrative indicators (resource use and personnel management) by the ASA. These indicators, or performance measures, could then be collected and stored in a relational database along with demographic data about providers. The ASA did not believe that participation should be required for any aspect of their database registry, but did recognize that, with time, there may be increasing external pressures to participate. In 2005, CPOM believed these pressures were likely to come from national, regional, or local organizations that demand evidence of participation in an outcomes database system, or require the comparison of the outcomes of groups or individual providers with national benchmarks [16]. Carolyn Clancy, Director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), confirmed this sentiment in July 2009, when she stated that physicians who want to obtain government funds should prepare themselves by using registries to collect data [17].

Clinical outcome registries and the AQI

In October 2008, the ASA House of Delegates approved funding for the AQI that was chartered in December of the same year. Although established by the ASA, the AQI is a separate organization that intends to become the primary source of information for performance measurement, and subsequent quality improvement, in the clinical practice of anesthesiology. This information is managed in the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry (NACOR). The AQI expects to have 20 anesthesia groups participating in NACOR by the end of 2010. Currently, the bulk of the data being collected are electronic claims data, but the plan for the future is to collect data from automated anesthesia records [18].

Although an administrative data source answers questions about case type and case length, it is not suited for judging physician performance. The validity of administrative data to measure clinical performance, or lend applicability to risk adjustment, has been challenged. Lee and colleagues [19] showed that administrative data could fail to detect up to 55% of cases of preexisting renal disease, nearly 65% of previous myocardial infarctions, and 75% of preexisting cerebrovascular disease. In a more recent study, Romano and colleagues [20] compared National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) data, which were manually abstracted from medical records, with AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators, which were collected via the administrative system based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (Clinically Modified) (ICD-9-CM), and found that the latter missed 44% of cases of pulmonary embolus or deep venous thrombosis, 68% of postoperative sepsis, 71% of wound dehiscence, and 80% of the occurrences of postoperative respiratory failure. This lack of validity of administrative data, and the perception that the federal government lacks sufficient concern over assuring validity in hospital comparison data that are made public, have led some anesthesiologists to suggest that the best course of action for AQI would be to combine forces with the American College of Surgeons (ACS) in the development of NSQIP in the public sector [21].

The NSQIP was developed by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in response to a 1986 congressional mandate to report risk-adjusted surgical outcomes annually, and to compare their outcomes with national averages. Perioperative performance measurement had not advanced to the point at which risk-adjusted national averages existed. In response, NSQIP developed risk-adjustment models for 30-day morbidity and mortality after major surgery in 8 surgical subspecialties and for all operations combined.

Measuring only performance and making the data public seems to have had a profound effect. In NSQIP’s first 10 years, the 30-day postoperative mortality decreased by 27%. Beginning with a 30-day mortality of 3.1% for major surgery in 1991, it decreased to 2.2% in 2002. An even more dramatic decline has been seen in postoperative morbidity. The number of patients undergoing major surgery in the NSQIP who experienced one or more of 20 predefined postoperative complications decreased from 17.8% to 9.8% in 10 years. The median length of stay declined by 5 days. Although data are unpublished, NSQIP administrators believed that these initial results justified the cost [22].

The cost of NSQIP data collection and analysis has been quoted at approximately $38 per case. The VHA database is expanding by approximately 100,000 cases annually and currently has more than 1 million cases. Thus, the cost to date has been more than $38 million dollars, yet private sector hospitals are still lining up to participate as they expand this project beyond the VHA hospitals under the auspices of the ACS. In ACS NSQIP, each hospital is expected to pay $35,000 annually, plus the cost of a trained nurse data collector, which should be about $50,000 per year, depending on regional wages. The VHA made this investment because of a 1986 Congressional mandate to compare their outcomes with national benchmarks after accusations of substandard care for veterans. When compared with 14 academic centers in the private sector, the VHA showed comparable morbidity and mortality, but that was after the VHA had maximized their initial improvement. Maybe continued improvement is no longer possible, leaving the continued high cost of database management unjustified [22].

Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement

External pressures to improve accountability for the practice of anesthesiology have come from several sources. In 1997, the American Medical Association (AMA) introduced the American Medical Accreditation Program (AMAP), in partnership with state and county medical associations and national medical specialty societies, as a method for physicians to submit their credentials to multiple health care organizations in a single approved format. Physicians who were associated with multiple health plans and hospitals underwent fragmented and duplicative processes for credentialing, and were often evaluated against multiple, and sometimes conflicting, criteria [23]. Before AMAP, no nationally recognized program existed for individual physician accreditation. To satisfy the increasing demand for physician accountability, this standardized credentialing system was to include AMAP-approved physician level performance measures. Although AMAP failed from a business standpoint [24], it spawned the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), an amalgam of committees that previously advised AMAP. This physician-led consortium included representatives of the 24 national medical specialty societies comprising the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and was charged with developing evidence-based clinical performance measures that would enhance quality of patient care and foster accountability. Today, PCPI comprises more than 170 national medical specialty societies, state medical societies, the ABMS member boards, Council of Medical Specialty Societies, health care professional organizations, federal agencies, individual members and others interested in improving the quality of patient care and accountability of physicians.

Performance Measures Relevant to Anesthesiology

As of October 2007, the PCPI, in conjunction with the ASA, had produced 5 measures relevant to anesthesiology and critical care [25]. These measures are geared toward:

Other measures relevant to anesthesiologists are shown in Box 2.

Box 2 Performance measures relevant to the practice of anesthesiology

Measures copyrighted by the AMA PCPI

Measures under development/consideration by the AMA PCPI

Measures proposed by the ASA Committee on Performance and Outcomes Measurement in 2007a

a These proposed measures are committee work products and not necessarily endorsed by the ASA.

Although these measures were designed for individual quality improvement, PCPI believes that these measures are appropriate for accountability if methodological, statistical, and implementation rules are achieved. Because these are process measures, risk adjustment is not required as long as appropriate exclusions are applied to the denominator when measuring compliance rates. For process measures, PCPI provides 3 categories of reasons for which a patient may be excluded from the denominator of an individual measure: medical reasons (eg, not indicated or contraindicated); patient reasons (eg, patient declines for economic, social or religious reasons); or system reasons (eg, resources not available, or payor-related limitations) [26].

Physician Quality Reporting Initiative

The first 3 PCPI measures listed earlier have already been incorporated into the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI). In this pay-for-reporting initiative, successfully reporting on 80% of the patients included in all 3 measures can earn up to 2% of the total Medicare Part B allowed charges for covered professional services [27]. Reporting is carried out via the Medicare claims form as CPT II codes/modifiers. Although PQRI is currently a pay-for-reporting initiative with positive financial incentives, it is likely to evolve into a pay-for-performance system with negative financial incentives for poor performers.

Judging Clinical Competence Under Special Circumstances

Although judging clinical competence is difficult for all physicians, certain situations make this a particularly daunting task for anesthesiologists. These situations include physicians in training, physicians approaching the end of their careers, and physicians returning to work after recovering from a substance abuse disorder. Common to these situations is the dynamic nature of clinical competence and the potential for rapid change. Rapid changes in clinical competence can be associated with patient harm, if the warning signs are not recognized and appropriate steps are not taken.

Anesthesiologists in Training

The most straightforward time to evaluate a physician’s competence is when they are in training, because evaluation during medical education is the most developed. At this stage the obstacles to certification are significant. Accredited medical schools and residencies are overseen by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which has established guidelines for the competency-based educational component of graduate medical education. There are formal requirements for continuous performance evaluation with feedback to students and residents. In addition, residents are required to evaluate their programs to ensure that their educational needs are being met. The ABMS has established certification as a rigorous process, in which success requires passing written and oral board examinations. Thus, initial certification is, in many ways, the gold standard against which future physician evaluation should be measured.

The ACGME is a private, nonprofit council that evaluates and accredits medical residency programs in the United States. ACGME’s Outcome Project requires residency programs to teach 6 core competencies, create tools to assess learning of the competencies, and to use the assessment data for program and resident improvement. The ACGME summarizes the change from a minimal threshold model to one that looks at the success of programs in teaching the 6 core competencies.

In the competency-based model, toward which the Outcome Project is directed, programs are asked to show how residents have achieved competency-based educational objectives and, in turn, how programs use information drawn from evaluation of those objectives to improve the educational experience of the residents. The minimal threshold model identifies whether a program has the potential to educate residents; the competency-based model examines whether the program is educating them.

Traditionally, anesthesia residents have been evaluated directly by their supervising faculty members, and in many cases they are judged by their performance on the In-Training Examination. The Outcome Project asks for more rigorous and detailed evaluation of residents. It seeks reliable tools to assess each of the competencies listed earlier. Global resident evaluations and In-Training Examinations should remain, but training programs need to have more refined performance evaluation tools [28]. The University of Florida, for example, has attempted to connect resident evaluation to evidence-based clinical outcomes. Clinical process measures are identified with high levels of existing data supporting their use (eg, aspirin for acute myocardial infarction). Next, the residents are evaluated in terms of success in applying these measures. Then, the feedback is used to improve resident performance and patient care. Clinical deficiencies can be used to help improve the program, and therefore to identify gaps in didactics [29].

Anesthesiology programs are likely to have a more difficult time implementing high-quality evidence-based outcomes measures to evaluate resident performance than other specialty training programs, such as internal medicine. As noted earlier, the lack of valid, risk-adjusted, outcome measures in anesthesiology makes comparative performance assessment difficult. The limited number of evidenced-based performance measures makes it impossible to use such data to evaluate overall resident performance. A concrete example of this is the resident who times the administration of prophylactic antibiotics perfectly, but thinks that every episode of tachycardia in the operating room should immediately be treated with β-blockers.

To provide assurance to the public that a physician specialist certified by a Member Board of the ABMS has successfully completed an approved educational program and evaluation process, which includes an examination designed to assess the knowledge, skills, and experience required to provide quality patient care in that specialty [30].

On further examination, one might challenge the underlying significance of performance measurement during medical school and residency training. One might even challenge the belief that certified practitioners are better than noncertified practitioners. However, starting with medical school, lack of professional behavior is predictive of poor career performance. In a 2005 publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, a group from the University of California at San Francisco reported that disciplinary action among practicing physicians by medical boards is strongly associated with unprofessional behavior in medical school. They concluded “professionalism should have a central role in medical academics and throughout one’s medical career” [31]. The same group found that examination performance and professionalism ratings during internal medicine residency were associated with a lower risk of subsequent disciplinary action [32]. Within anesthesiology, there has been validation of the faculty evaluation of residents’ clinical skills as a predictor of their subsequent success on the certification examination. Furthermore, there is a strong association between failure of the certification examination and deficiency in personality traits associated with successful practice of anesthesiology [33]. A more recent study showed the expected connection between success on the ABA In-Training Examination (taken during residency) and shortest time to ABA certification [34].

Certification and quality are also linked once resident training is completed. In both cardiology and surgery, several studies have found an association between certification and compliance with guidelines and, in some cases, lower mortality [35].

In addition, a study of midcareer anesthesiologists links poor outcomes to nonboard-certified physicians [36]. Thirty-day mortality and failure-to-rescue rates were higher for noncertified anesthesiologists than for their certified counterparts in midcareer. The investigators looked at midcareer anesthesiologists to allow ample time to have attempted certification, and to exclude older physicians who trained when there was less emphasis on board certification. Although this retrospective review of Medicare claims data suggests an association between lack of ABA certification and poor outcomes, it cannot prove causation. The hospitals with more noncertified anesthesiologists had poorer outcomes, but the patients who go to such hospitals may also be different (less healthy in both measured and unmeasured dimensions) than those who go to hospitals with certified anesthesiologists.

The Aging Anesthesiologist

A combination of demographic and economic factors has led to forecasts predicting continued demand for older anesthesiologists. An older population has increased need for surgery, and this, combined with the shortage of anesthesiologists trained in the 1990s, leads to a future shortfall in anesthesiologists to care for these patients [37]. In addition, the recent downturn in retirement accounts may lead to physicians opting to work later in life. Aging anesthesiologists present particular challenges for at least 2 reasons. First, the scope of the problem is enormous: all anesthesiologists are aging. Second, there is no discreet moment at which one’s practice goes from experienced to obsolete. Losing skills parallels physical aging: it happens gradually, but eventually it happens to all of us.

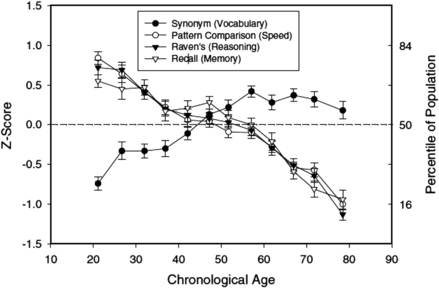

Katz [38] highlighted the myriad of complex issues facing the aging anesthesiologist in a review article. Although potentially we gain wisdom and experience as we age, we are also subject to physical and mental changes that may impede our ability to continue to practice safely in the dynamic operating room environment. Normal age-associated physical and cognitive decline makes the practice of anesthesiology particularly challenging as we age. Contrary to the widely held assumption that age-related cognitive decline typically occurs in our 70s, recent evidence suggests it begins in our 20s. Timothy Salthouse and his laboratory at the University of Virginia have examined decline across 4 cognitive dimensions: vocabulary, pattern recognition speed, memory, and reasoning. Vocabulary increases into our 50s, but all other components of cognitive function show substantial decline beginning in our 20s (Fig. 1). The magnitude of the age-related cognitive decline in speed, pattern recognition, and memory are more substantial than most of us realize: “Performance for adults in their early 20s was near the 75th percentile in the population, whereas the average for adults in their early 70s was near the 20th percentile” [39].

Fig. 1 Cognitive function declines linearly with age starting in our 20s. Means (and standard errors) of performance in four cognitive tests as a function of age. Each data point is based on between 52 and 150 adults.

(Data from Salthouse TA. What and when of cognitive aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2004;13:140–4.)

In light of such significant cognitive decline, how can anesthesiologists continue to function well into their 50s and 60s? First, cognitive ability is only one element of successful performance of a task. We draw on motivation and persistence, as well as patience, which may not decline with age. Second, we can adapt our environment to avoid negative consequences of our cognitive decline. Anesthesia is often practiced in a care team model. In that setting, a physician may hide diminished skills by allowing others to do the more challenging tasks. Even in a personally administered care setting, those organizing the schedule may often assign less complicated cases to those with limited skills. Familiarity of environment (practice setting/case mix) may minimize cognitive challenges as we age. In addition, safe care demands that we ask for help when we have trouble with a given task; thus, it is good practice to seek help. Salthouse and his colleagues found that increases in knowledge and experience may offset cognitive decline; for example, older adults perform remarkably well on crossword puzzles compared with their younger counterparts.

Because anesthesiology is a form of shift work, it is important to remark on the interaction between aging and shift work. The effect is not at all straightforward. Age is associated with well-recognized patterns of sleep disturbance, but vigilance under conditions of extreme sleep deprivation is diminished more in younger than in older workers [40]. Conversely, need for recovery (an index of fatigue) after shift work is increased in older workers [41]. Older workers perform well, remaining vigilant during long shifts, but have more trouble with recovery from those shifts. Aging anesthesiologists would be expected, then, still to perform well at night but to have more trouble with the postcall recovery.

Clinical competence, as judged by ABA certification, is not based on a recertification examination for anyone who has been certified since 1999. Therefore, those anesthesiologists whose training is most out of date are exempt from the MOCA recertification process. Residencies have only recently incorporated lifelong learning as a competency required of their graduates, and previous anesthesiology professional training may not have adequately prepared the aging anesthesiologist for the challenges they face. Those anesthesiologists participating in MOCA are required to maintain professional standing acceptable to the ABA and to show cognitive expertise through written examination every 10 years. In addition, MOCA requires practice performance assessment and improvement that includes simulation-based education during the 10-year cycle. If MOCA evolves from simulation-based education to simulation-based assessment at more frequent intervals, it may offer another means of competency assessment for the aging anesthesiologist.

Acting on age-related decline in competency does have legal implications. These legal issues can be complex, but some background information is useful. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) protects individuals who are 40 years of age or older from employment discrimination based on age. There are some notable exceptions and the 2 most important are:

ADEA is not meant to prohibit termination with cause. If there are reasonable grounds for termination with cause, ADEA does not prevent that.

This is the basis on which pilots and police officers are often age limited: age is an essential proxy to protect public safety.

The burden of proof for BFOQ lies with the employer and can be severe. For example, the Supreme Court found that just because airlines can limit pilot duties, this does not mean that pilots cannot continue to work as flight engineers [42,43]. According to a 2005 study by Altman Weil, a law firm consultancy, 57% of law firms with 100 or more attorneys enforce a mandatory retirement age, which typically ranges from ages 65 to 75 years [44]. Most law firms are arranged as partnerships among owners and, therefore, may be exempt from the age discrimination claims that would arise if an employer were to have a mandatory retirement for employees. Employers using the BFOQ defense against charges of age discrimination must show either: (1) that it is reasonable to believe that all or most employees of a certain age cannot perform the job safely, or (2) that it is impossible or highly impractical to test employees’ abilities to tackle all tasks associated with the job on an individualized basis. For example, an employer who refuses to hire anyone more than 60 years old as a pilot has a potential BFOQ defense if there is a reasonable basis for concluding that pilots aged 60 years or older pose significant safety risks, or that it is not feasible to test older pilots individually. In light of the substantial legal burden on employers wishing to enact age-based retirement rules, mandatory retirement policies are likely to continue to face legal hurdles preventing them from becoming widespread within anesthesiology. Therefore, a more feasible goal is to develop practical performance measures, and to enhance CME requirements; replacing educational vacations with simulation-based training.

Recovery from Substance Abuse Disorders

It is widely known that anesthesiologists are at risk for substance abuse. According to one study, there is a 34% increased rate of death from accidental overdose [45]. Another study showed a 7-fold increase in risk of substance abuse among anesthesia residents compared with other fields [46]. Although the impaired physician would likely be one whose performance is poor, there are no clear data to support this hypothesis. Many believe that impairment itself implies a substantial performance deficiency in a field whose motto is “Vigilance.” We lack the technology and infrastructure to perform rigorous simulation assessments required to show retained competence of older anesthesiologists. In time, computer-based simulation exercises may reassure us that an aging physician is still fit for the task (analogous to Federal Aviation Administration pilot requirements). By contrast, there is no examination, peer review, or simulation training for a physician recovering from a substance abuse disorder that could establish conclusively if or when it is safe to return to work.

Most providers with a history of substance abuse are allowed to return to work with mandatory surveillance. Despite this, there is a tremendous relapse rate. High rates of recidivism likely stem from easy access to drugs, stressful work conditions, and poorly understood physiologic predisposition to addiction [47]. Coexisting psychiatric illness and family history have been found to be predictive of relapse [48]. In a study of drug- and alcohol-abusing patients who underwent liver transplantation, an additional predictor of relapse included being less than 1 year beyond a time of previous alcohol abuse [49]. A recent editorial from the Mayo Clinic, published in Anesthesiology, called for a sea change in our approach to the impaired anesthesiologist. They called for a “one strike and you’re out” policy that would bar the substance-abusing physician from future anesthesia practice. Substance abusers could retrain in another field of medicine that has fewer environmental triggers for relapse [50].

Assessing the fitness of a recovering addict to return to work has some features in common with assessing the competency of a resident or an aging physician. However, an important distinction is that in one case we are assessing quality of medical care and in the other we are looking for signs that a poorly understood clandestine behavior or disease is recurring or remains in remission. For the recovering addict there is little evidence to show that they are at low risk for relapse. The ethical questions raised here are common to many of these issues. How should we balance the rights of the individual against the rights of the community? Is it really just to maintain that there is no course of treatment an impaired physician could undergo, and no amount of time without relapse, that would allow the likelihood of safe practice? And, although we may believe that we are standing on principle, are we really? If the principle is to absolutely protect our patients from physicians who are potentially impaired, then should we not strictly apply an age limit in the field (if it were legal) because practitioners in their 70s and 80s are more likely to suffer from dementia? Substance abuse presents many of the same issues as aging; in both cases, it is a challenge to evaluate competence in an environment with the potential for rapid change and the potential for patient harm.

Policing Our Own in Anesthesiology

Many physicians ask, “If we had an independent measure of a licensed, certified practitioner’s competence, would we really need to use it?” Should not physicians themselves determine whether or not they are competent? The answer is, definitely not. Human beings are poor at assessing their own expertise. According to the British philosopher Bertrand Russell, “the trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure, and the intelligent are full of doubt” [51]. The problem has come to be known as the Kruger-Dunning effect [52]. These 2 psychologists studied competence in many areas and found that in virtually every area:

It is difficult, unwise, and ultimately dangerous, to depend on self-assessment as a way of safeguarding patients from unskilled practitioners. Most professions suffer from this same problem, as discussed in the recent book, Why We Make Mistakes [53].

In a recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine, 2 leaders of the modern patient safety movement addressed the lack of individual accountability within hospitals [54]. Wachter and Pronovost provide a scathing assessment of the failure of hospitals and physicians to police their colleagues on such basic measures as hand hygiene. Virtually all of the focus of modern patient safety literature has focused on system failures, which are important, but there has been little attention to the consequences of the failing physician. In many cases, one’s colleagues know that a practitioner is a low performance outlier and yet fail to intervene. This situation happens in many cases because there is little institutional, or departmental, support for genuinely holding physicians accountable. Generally speaking, only when there is a negative financial consequence, such as incomplete charts or malpractice litigation, do hospitals hold practitioners truly accountable. In situations as obvious as failure to wash one’s hands, hospitals and departments usually look the other way.

Wachter and Pronovost summarize the problem as follows. In the first decade of the patient safety movement, the focus was on systems issues and engineering solutions (eg, computerized order entry and checklists). However, identification of system-wide safety problems is hindered when employees fail to report near misses or mistakes. Creating a culture for hospital workers to speak up when they see signs of an unsafe environment within their organization has been conflated with a false imperative to create a no-blame culture. No-blame must not become no-consequences-for-any-action, no matter how dangerous, or how clear the rules. The concept that we constantly hold physicians accountable to a high set of standards is the justification for many of our own professional societies’ assertions that government should leave physician regulation to physicians. Wachter and Pronovost conclude that without self-regulation we will face more public regulation:

Part of the reason we must do this is that if we do not, other stakeholders, such as regulators and state legislatures, are likely to judge the reflexive invocation of the “no blame” approach as an example of guild behavior — of the medical profession circling its wagons to avoid confronting harsh realities, rather than as a thoughtful strategy for attacking the root causes of most errors. With that as their conclusion, they will be predisposed to further intrude on the practice of medicine, using the blunt and often politicized sticks of the legal, regulatory, and payment systems [54].

Summary

Physicians are granted a great deal of autonomy and self-governance as a profession uniquely entrusted to protect their patients. Every major professional medical body attempts to conform to the Hippocratic Oath to “do no harm.” This practice contrasts with a norm of allowing physicians to completely self-determine whether they are competent to care for patients, when they should retire, and when it is safe to return to work after recovering from a substance abuse disorder. Anesthesiologists are not required to wait for a death or major disability before limiting a colleague from practicing anesthesia. There must be a point at which loss of skills and obsolescence of knowledge compel us to prevent an anesthesiologist from continuing to treat patients. In an idealized society, that point should come before patient safety is jeopardized. This goal does not begin with a culture of blame and shame, but neither does it stem from a relativistic attitude that any licensed practitioner is equally good as any other. It is a myth that physicians are somehow different from pilots or athletes. Given enough time, through the process of normal aging, all of us lose the requisite skills to practice safely. Defining a specific age at which that happens is likely to be impossible, but the reality is no different for anesthesiologists than it is for pilots. As is often noted, the consequences for the pilot working with outdated skills are more dire for the pilot than they are for a physician. Despite this, independent regulatory bodies still require commercial pilots to undergo rigorous simulator-based assessments twice a year and prohibit them from working beyond age 65 years. In anesthesiology we need to demand independent assessment of competence even for senior members. “Grandfathering in” makes no sense when patient safety and competence are at issue. Anesthesiology, as a profession, must embrace the science of performance measurement and overcome the barriers to judging clinical competence. If anesthesiology is going to remain at the forefront of the patient safety movement, judging clinical competence is going to require better quality metrics with improved statistical power and appropriate risk adjustment, genuine peer assessment of valid indicators, and frequent written examination and assessments in simulated clinical environments.

References

[1] Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health care system. In: Kohn L, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. p. 241.

[2] Sentinel events. approaches to error reduction and prevention. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:175-186.

[3] R.S. Lagasse. Anesthesia safety: model or myth? A review of the published literature and analysis of current original data. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1609-1617.

[4] J.H. Eichhorn. Prevention of intraoperative anesthesia accidents and related severe injury through safety monitoring. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:572-577.

[5] Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. p. 364

[6] Federation of State Medical Boards. Available at: http://www.fsmb.org/. Accessed August 27, 2010.

[7] Physician Accountability for Physician Competence. Available at: http://innovationlabs.com/summit. Accessed August 27, 2010.

[8] T.S. Vitez. A model for quality assurance in anesthesiology. J Clin Anesth. 1990;2:280-287.

[9] T. Vitez. Judging clinical competence. Park Ridge (IL): American Society of Anesthesiologists; 1989.

[10] R.A. Gabel. Quality assurance/peer review for recredentialing/relicensure in New York State. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1992;30:93-101.

[11] Lagasse R, Akerman M. The power of peer review: human error rates as a measure of anesthesiologists’ clinical competence [abstract]. American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting. San Diego (CA); 2010. p. A386.

[12] S.D. Edbril, R.S. Lagasse. Relationship between malpractice litigation and human errors. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:848-855.

[13] G. Haller, J. Stoelwinder, P.S. Myles, et al. Quality and safety indicators in anesthesia: a systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1158-1175.

[14] A. Donabedian. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring: the criteria and standards of quality. Ann Arbor (MI): Health Administration Press; 1982.

[15] Fourth Annual Disease Management Outcome Summit. Outcomes-based compensation: pay-for-performance design principles. Nashville (TN): American Healthways, Inc; 2004.

[16] Committee on Performance and Outcome Measures. Annual Report to the ASA House of Delegates. Park Ridge (IL): American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2005.

[17] R. Johnstone. Convergence of large group studies and individual performance measures. ASA Newsl. 2010;74(5):10-11.

[18] R. Dutton. Counterpoint: out with the old, in with the new. ASA Newsl. 2010;74(5):18-19.

[19] D.S. Lee, L. Donovan, P.C. Austin, et al. Comparison of coding of heart failure and comorbidities in administrative and clinical data for use in outcomes research. Med Care. 2005;43:182-188.

[20] P.S. Romano, H.J. Mull, P.E. Rivard, et al. Validity of selected AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators based on VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:182-204.

[21] L. Glance. A roadmap for the AQI – one anesthesiologist’s opinion. ASA Newsl. 2010;74(5):16-17.

[22] R.S. Lagasse. The right stuff: Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Project. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1772-1774.

[23] K. Kmetik. Physician performance measurement and improvement in the American Medical Accreditation Program (AMAPSM), Clinical practice applications. Hanover: Medical Outcomes Trust; 1998.

[24] J. Frieden. AMAP is dead (American Medical Accreditation Program). Ob Gyn News, March 15. Farmington Hills. (MI): Gale Group; 2000.

[25] Committee on Performance and Outcome Measures. Annual Report to the ASA House of Delegates. Park Ridge (IL): American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2007.

[26] American Society of Anesthesiologists and Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement® Anesthesiology and Critical Care Physician Performance Measurement Set. Chicago (IL): American Medical Association; 2007.

[27] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services – PQRI Overview. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/pqri/. Accessed August 27, 2010.

[28] J.E. Tetzlaff. Assessment of competency in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:812-825.

[29] C. Haan, F. Edwards, B. Poole, et al. A model to begin to use clinical outcomes in medical education. Acad Med. 2008;83:574-580.

[30] J.W. Jones, L.B. McCullough, B.W. Richman. Who should protect the public against bad doctors? J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:907-910.

[31] M.A. Papadakis, A. Teherani, M.A. Banach, et al. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2673-2682.

[32] M.A. Papadakis, G.K. Arnold, L.L. Blank, et al. Performance during internal medicine residency training and subsequent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:869-876.

[33] S. Slogoff, F.P. Hughes, C.C. HugJr., et al. A demonstration of validity for certification by the American Board of Anesthesiology. Acad Med. 1994;69:740-746.

[34] J.C. McClintock, G.P. Gravlee. Predicting success on the certification examinations of the American Board of Anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:212-219.

[35] K. Sutherland, S. Leatherman. Does certification improve medical standards? BMJ. 2006;333:439-441.

[36] J.H. Silber, S.K. Kennedy, O. Even-Shoshan, et al. Anesthesiologist board certification and patient outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1044-1052.

[37] K.K. Tremper, A. Shanks, M. Morris. Five-year follow-up on the work force and finances of United States anesthesiology training programs: 2000 to 2005. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:863-868.

[38] J.D. Katz. Issues of concern for the aging anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1487-1492.

[39] T.A. Salthouse. What and when of cognitive aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13:140-144.

[40] M. Adam, J.V. Retey, R. Khatami, et al. Age-related changes in the time course of vigilant attention during 40 hours without sleep in men. Sleep. 2006;29:55-57.

[41] P. Kiss, M. De Meester, L. Braeckman. Differences between younger and older workers in the need for recovery after work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81:311-320.

[42] Western Airlines v Criswell 472, US 400.

[43] K. Ford, K. Notestine, R. Hill. Fundamentals of employment law: tort and insurance practice section, 2nd edition. Chicago (IL): American Bar Association; 2000.

[44] Jones L. ABA takes stand against mandatory retirement. Natl Law J; 2007. Available at: http://www.law.com/jsp/nlj/PubArticleNLJ.jsp?id=900005488594&slreturn=1&hbxlogin=1. Accessed August 28, 2010.

[45] B.H. Alexander, H. Checkoway, S.I. Nagahama, et al. Cause-specific mortality risks of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:922-930.

[46] G.D. Talbott, K.V. Gallegos, P.O. Wilson, et al. The Medical Association of Georgia’s Impaired Physicians Program. Review of the first 1000 physicians: analysis of specialty. JAMA. 1987;257:2927-2930.

[47] E.O. Bryson, J.H. Silverstein. Addiction and substance abuse in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:905-917.

[48] K.B. Domino, T.F. Hornbein, N.L. Polissar, et al. Risk factors for relapse in health care professionals with substance use disorders. JAMA. 2005;293:1453-1460.

[49] R. Gedaly, P.P. McHugh, T.D. Johnston, et al. Predictors of relapse to alcohol and illicit drugs after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Transplantation. 2008;86:1090-1095.

[50] K.H. Berge, M.D. Seppala, W.L. Lanier. The anesthesiology community’s approach to opioid- and anesthetic-abusing personnel: time to change course. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:762-764.

[51] B. Russell. Marriage and morals. New York: Liveright; 1957.

[52] J. Kruger, D. Dunning. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:1121-1134.

[53] J.T. Hallinan. Why we make mistakes: how we look without seeing, forget things in seconds, and are all pretty sure we are way above average, 1st edition. New York: Broadway Books; 2009.

[54] R.M. Wachter, P.J. Pronovost. Balancing “no blame” with accountability in patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1401-1406.