Chapter 10

The Chest

In the beginning the malady [tuberculosis] is easier to cure but difficult to detect, but later it becomes easy to detect but difficult to cure.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527)

General Considerations

Oxygen enables the breath of life; without adequate lung function, lives cannot be sustained. Patients with pulmonary disease must work harder for adequate oxygenation. These patients complain of “air hunger” or “too little air.” Anyone who has traveled to areas of high altitude, where the oxygen concentration is reduced, has experienced shortness of breath.

The magnitude of pulmonary disease is enormous. Whereas the top two causes of death, heart disease and cancer, have seen a drop in their mortality rate, lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen the largest rise of any leading cause of death. COPD is now the third leading cause of death in the United States, surpassing stroke.

The symptoms of COPD include breathlessness, chronic coughing (with or without mucus), wheezing, tightness in chest, and frequent clearing of the throat. Here are the facts:

• A person with COPD dies every 4 minutes in the United States.

• In 2007, COPD cost the United States economy $42.6 billion in direct and indirect costs.

• It is estimated that more than 600 million people worldwide have COPD.

COPD is a preventable and treatable condition. Almost 90% of COPD is due to smoking, and smoking cessation at any age and stage of disease is beneficial.

Cancer of the lung and bronchus is the leading cause of death from cancer in the United States in both men (28% of all cancer deaths) and women (26% of all cancer deaths). In 2011, the American Cancer Society reported that there were 221,130 new cases of lung and bronchus cancer. Cancer of the lung and bronchus is the second most common cancer in men (14%) after prostate cancer and second most common in women (14%) after breast cancer. There were 156,940 deaths, of which 85,600 were deaths in men and 71,340 deaths in women.

The 1-year relative survival for lung cancer increased from 35% in 1975 to 1979 to 43% in 2003 to 2006, largely because of improvements in surgical techniques and combined therapies. However, the 5-year survival rate for all stages combined is only 16%. The 5-year survival rate is 53% for cases detected when the disease is still localized, but only 15% of lung cancers are diagnosed at this early stage. The 5-year survival for small cell lung cancer (6%) is lower than that for non–small cell (17%).

Pulmonary diseases arise when the lungs are unable to provide adequate oxygenation or to eliminate carbon dioxide. Any derangement of these functions indicates abnormal respiratory function.

During a 24-hour period, the lungs oxygenate more than 5700 L of blood with more than 11,400 L of air. The total surface area of the alveoli of the lungs comprises an area larger than a tennis court.

Structure and Physiology

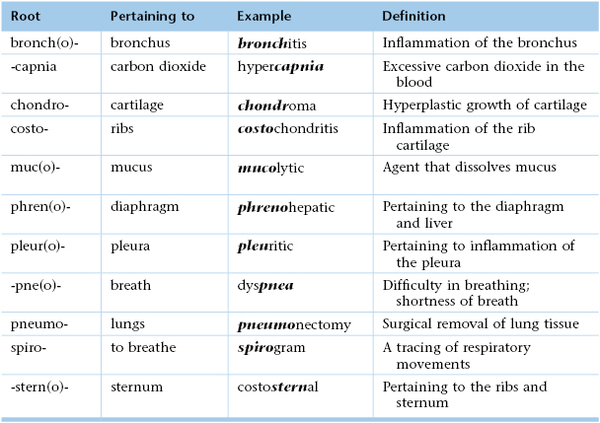

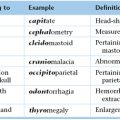

The chest forms the bony case that houses and protects the lungs, the heart, and the esophagus as it passes into the stomach. The chest skeleton consists of 12 thoracic vertebrae, 12 pairs of ribs, the clavicle, and the sternum. The bony structure is illustrated in Figure 10-1.

Figure 10–1 Bony chest skeleton.

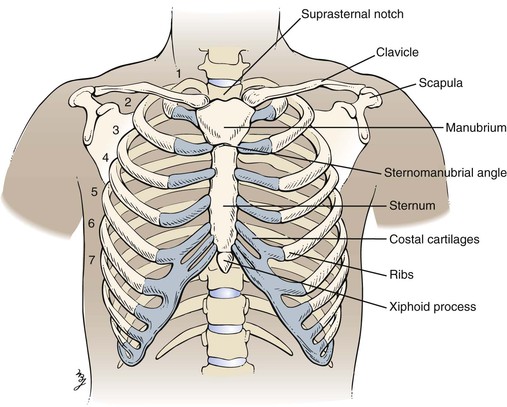

Inspired air is warmed, filtered, and humidified by the upper respiratory passages. After passing through the cricoid cartilage of the larynx, air travels through a system of flexible tubes, the trachea. At the level of the fourth or fifth thoracic vertebra, the trachea bifurcates into the left and right bronchi. The right bronchus is shorter, wider, and straighter than the left bronchus. The bronchi continue to subdivide into smaller bronchi and then into bronchioles within the lungs. Each respiratory bronchiole terminates in an alveolar duct, from which many alveolar sacs branch off. It is estimated that there are more than 500 million alveoli in the lungs. Each alveolar wall contains elastin fibers that allow the sac to expand with inspiration and to contract with expiration by elastic recoil. This system of air-conducting passages is illustrated in Figure 10-2.

Figure 10–2 System of air-conducting passages.

The lungs are subdivided into lobes: the upper, middle, and lower on the right, and the upper and lower on the left. The lungs are enveloped in a thin sac, the pleura. The visceral pleura overlies the lung parenchyma, whereas the parietal pleura lines the chest wall. The two pleural surfaces glide over each other during inspiration and expiration. The space between the pleura is the pleural cavity.

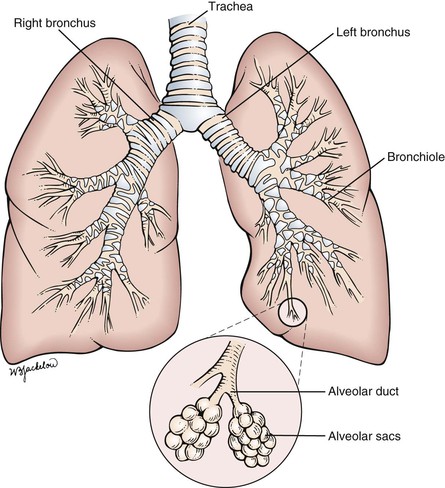

To describe physical signs in the chest accurately, the examiner must understand the topographic landmarks of the chest wall. The landmarks of clinical importance are as follows:

Figure 10-3 illustrates the anterior and lateral views of the thorax, and Figure 10-4 illustrates the posterior thorax.

Figure 10–3 Thoracic cage landmarks. A, Topographic landmarks of the anterior thorax. B, Landmarks on the lateral view.

Figure 10–4 Topographic landmarks of the posterior thorax.

The suprasternal notch is located at the top of the sternum and can be felt as a depression at the base of the neck. The sternomanubrial angle is often referred to as the angle of Louis. This bony ridge lies approximately 5 cm below the suprasternal notch. When you move your fingers off the ridge laterally, the adjacent rib that you feel is the second rib. The interspace below the second rib is the second intercostal space. Using this as a reference point, you should be able to identify the ribs and interspaces anteriorly. Try it on yourself.

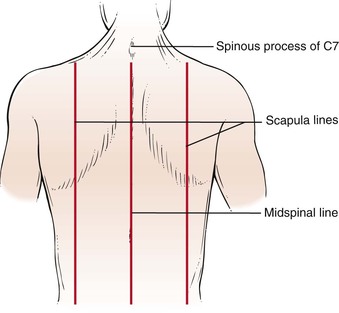

To identify areas, several imaginary lines can be visualized on the anterior and posterior chest in Figures 10-3 and 10-4. The midsternal line is drawn through the middle of the sternum. The midclavicular lines are drawn through the middle points of the clavicles and parallel to the midsternal line. The anterior axillary lines are vertical lines drawn along the anterior axillary folds parallel to the midsternal line. The midaxillary lines are drawn from each vertex of the axilla parallel to the midsternal line. The posterior axillary lines are parallel to the midsternal line and extend vertically along the posterior axillary folds. The scapular lines are parallel to the midspinal line and pass through the inferior angles of the scapulae. The midspinal line is a vertical line that passes through the posterior spinous processes of the vertebrae.

Rib counting from the posterior chest is slightly more complicated. The inferior wing of the scapula lies at the level of the seventh rib or interspace. Another useful landmark can be found by having the patient flex the neck; the most prominent cervical spinous process, the vertebra prominens, protrudes from the seventh cervical vertebra.

Only the first seven ribs articulate with the sternum. The eighth, ninth, and tenth ribs articulate with the cartilage above. The eleventh and twelfth ribs are floating ribs and have a free anterior portion.

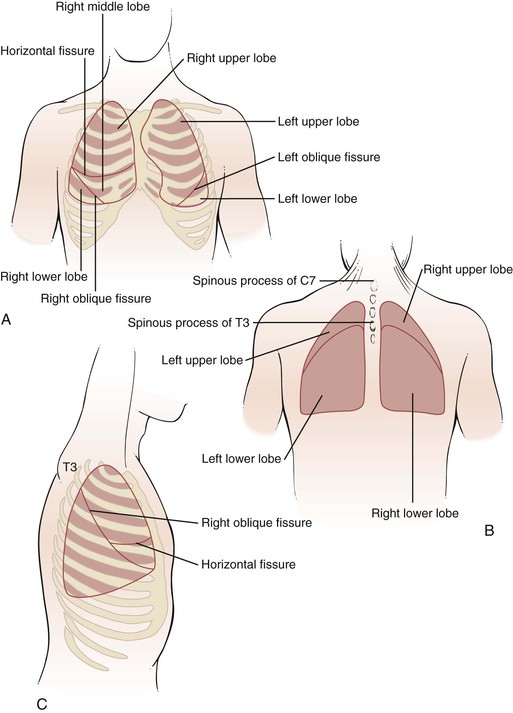

The interlobar fissures, illustrated in Figure 10-5, are situated between the lobes of the lungs. Both the right and the left lungs have an oblique fissure, which begins on the anterior chest at the level of the sixth rib at the midclavicular line and extends laterally upward to the fifth rib in the midaxillary line, ending at the posterior chest at the spinous process of T3. The right lower lobe is below the right oblique fissure; the right upper and middle lobes are superior to the right oblique fissure. The left lower lobe is below the left oblique fissure; the left upper lobe is superior to the left oblique fissure. The horizontal fissure is present only on the right and divides the right upper lobe from the right middle lobe. It extends from the fourth rib at the sternal border to the fifth rib at the midaxillary line.

Figure 10–5 Surface topography and the underlying interlobar fissures. A, Anterior view. B, Posterior view. C, Lateral view.

The lungs extend superiorly approximately 3 to 4 cm above the medial end of the clavicles. The inferior margins of the lungs extend to the sixth rib at the midclavicular line, to the eighth rib at the midaxillary line, and between T9 and T12 posteriorly. This variation is related to respiration. The bifurcation of the trachea, the carina, is located behind the angle of Louis at approximately the level of T4 on the posterior chest. The right hemidiaphragm at the end of expiration is located at the level of the fifth rib anteriorly and T9 posteriorly. The presence of the liver on the right side makes the right hemidiaphragm slightly higher than the left.

During quiet breathing, muscle contraction occurs only during inspiration. Expiration is passive, resulting from the elastic recoil of the lungs and chest.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The main symptoms of pulmonary disease are the following:

• Cough

• Hemoptysis (coughing up blood)

• Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

• Wheezing

• Cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin)

• Snoring

Cough

The most common symptom of lung disease is the cough. Coughing is so common that it is frequently regarded as a trivial complaint. The cough reflex is a normal defense mechanism of the lungs that protects them from foreign bodies and excessive secretions. Infections of the upper respiratory tract are associated with coughing that usually improves in 2 to 3 weeks. A persistent cough necessitates further investigation.

Coughing is a coordinated, forced expiration, interrupted by repeated closure of the glottis. The expiratory muscles contract against the partially closed glottis, creating high pressure within the lungs. When the glottis suddenly opens, there is an explosive rush of air that clears the air passages. When a patient complains of coughing, ask these questions:

“Can you describe your cough?”

“How long have you had a cough?”

“Was there a sudden onset of coughing?”

“Do you smoke?” If so, “What do you smoke? How much, and for how long?”

“Does the cough occur for prolonged periods?”

“Does the cough occur after eating?”

“Is the coughing worse in any position?”

Coughing may be voluntary or involuntary, productive or nonproductive. In a productive cough, mucus or other materials are expelled. A dry cough does not produce any secretions.

Smoking is probably the most common cause of the chronic cough. Smoker‘s cough results from inhalation of irritants in tobacco and is most marked in the morning. Coughing is normally decreased during sleep. When the smoker awakens, productive coughing tends to clear the respiratory passages. In patients who stop smoking, the cough decreases and may disappear.

Coughing may also be psychogenic. This nonproductive cough occurs in individuals with emotional stress. When attention is drawn to it, the cough occurs more often. During sleep, or when the patient is distracted, the coughing stops. Psychogenic coughing is a diagnosis of exclusion: Only after all other causes have been eliminated can this diagnosis be made.

There are many terms used by patients and physicians to describe a cough. Table 10-1 provides a list of some of the more common descriptors and their possible causes.

Table 10–1

Descriptors of Coughing

| Description | Possible Causes |

| Dry, hacking | Viral infections, interstitial lung disease, tumor, allergies, anxiety |

| Chronic, productive | Bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, abscess, bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis |

| Wheezing | Bronchospasm, asthma, allergies, congestive heart failure |

| Barking | Epiglottal disease (e.g., croup) |

| Stridor | Tracheal obstruction |

| Morning | Smoking |

| Nocturnal | Postnasal drip, congestive heart failure |

| Associated with eating or drinking | Neuromuscular disease of the upper esophagus |

| Inadequate | Debility, weakness |

Sputum Production

Sputum is the substance expelled by coughing. Approximately 75 to 100 mL of sputum is secreted daily by the bronchi. By ciliary action, it is brought up to the throat and then swallowed unconsciously with the saliva. An increase in the quantity of sputum production is the earliest manifestation of bronchitis. Sputum may contain cellular debris, mucus, blood, pus, or microorganisms.

Sputum should be described according to color, consistency, quantity, the number of times it is brought up during the day and night, and the presence or absence of blood. An adequate description may indicate a cause of the disease process. Uninfected sputum is odorless, transparent, and whitish-gray, resembling mucus; it is termed mucoid. Infected sputum contains pus and is termed purulent; the sputum may be yellow, greenish, or red. Table 10-2 lists the appearances of sputum and their possible causes.

Table 10–2

Appearances of Sputum

| Appearance | Possible Causes |

| Mucoid | Asthma, tumors, tuberculosis, emphysema, pneumonia |

| Mucopurulent | Asthma, tumors, tuberculosis, emphysema, pneumonia |

| Yellow-green, purulent | Bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis |

| Rust-colored, purulent | Pneumococcal pneumonia |

| Red currant jelly | Klebsiella pneumoniae infection |

| Foul odor | Lung abscess |

| Pink, blood-tinged | Streptococcal or staphylococcal pneumonia |

| Gravel | Broncholithiasis |

| Pink, frothy | Pulmonary edema |

| Profuse, colorless (also known as bronchorrhea) | Alveolar cell carcinoma |

| Bloody | Pulmonary emboli, bronchiectasis, abscess, tuberculosis, tumor, cardiac causes, bleeding disorders |

Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis is the coughing up of blood. Few symptoms produce as much alarm in patients as does hemoptysis. Careful description of the hemoptysis is crucial because what is produced can include clots of blood, as well as blood-tinged sputum. The implications of each are very different. Coughing up clots of blood is a symptom of extreme importance because it often heralds a serious illness. Clots of blood are usually indicative of a cavitary lung lesion, a tumor of the lung, certain cardiac diseases, or pulmonary embolism. Blood-tinged sputum is usually associated with smoking or minor infections, but it can be seen with tumors and more serious diseases as well. When a patient complains of coughing up blood, the examiner should ask the following questions:

“Do you smoke?” If yes, “What do you smoke? How much, and for how long?”

“Did the coughing up of blood occur suddenly?”

“Have there been recurrent episodes of coughing up blood?”

“Is the sputum blood-tinged, or are there actual clots of blood?”

“How long have you noticed the blood?”

“What seems to bring on the coughing up of blood? Vomiting? Coughing? Nausea?”

“Have you ever had tuberculosis?”

“Is there a family history of coughing up blood?”

“Have you had recent surgery?”

“Do you take any ‘blood thinners’?”

“Are you aware of any bleeding tendency?”

“Have you had any recent travel on airplanes?”

“Have you felt any unusual sensation in your chest after coughing up blood?” If so, “Where?”

(For a woman with hemoptysis) “Do you use oral contraceptives?”

Any suppurative (associated with the production of pus) process of the airways or lungs can produce hemoptysis. Bronchitis is probably the most common cause of hemoptysis. Bronchiectasis and bronchogenic carcinoma are also major causes. Hemoptysis results from mucosal invasion, tumor necrosis, and pneumonia distal to bronchial obstruction by tumor. Pneumococcal pneumonia characteristically produces rust-colored sputum. Pink and frothy sputum can result from pulmonary edema.

On occasion, patients have a warm sensation in the chest at the location from which the hemoptysis originated. Therefore it is useful to ask patients with recent hemoptysis whether they experienced such a sensation. This information may lead to a more careful review of the physical examination and x-ray films of that area.

Patients who have undergone recent surgery or have traveled for long periods on airplanes are at risk for deep vein thrombophlebitis with pulmonary embolism. Women taking oral contraceptives are likewise at risk for pulmonary embolic disease. Hemoptysis occurs when pulmonary emboli result in infarction, with necrosis of the pulmonary parenchyma.

Recurrent episodes of hemoptysis may result from bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, or mitral stenosis. Atrial fibrillation is a common cause of “irregular heartbeats” and embolic phenomena.

Sometimes it is difficult to ascertain whether the patient coughed up or vomited blood. Most patients can provide a sufficiently clear history. Table 10-3 lists characteristics that help distinguish hemoptysis from hematemesis (vomiting of blood).

Table 10–3

Characteristics Distinguishing Hemoptysis from Hematemesis

| Features | Hemoptysis | Hematemesis |

| Prodrome | Coughing | Nausea and vomiting |

| Past history | Possible history of cardiopulmonary disease | Possible history of gastrointestinal disease |

| Appearance | Frothy | Not frothy |

| Color | Bright red | Dark red, brown, or “coffee grounds” |

| Manifestation | Mixed with pus | Mixed with food |

| Associated symptoms | Dyspnea | Nausea |

Dyspnea

The subjective sensation of “shortness of breath” is dyspnea. Dyspnea is an important manifestation of cardiopulmonary disease, although it is found in other states such as neurologic, metabolic, and psychologic conditions. It is important to differentiate dyspnea from the objective finding of tachypnea, or rapid breathing. A patient may be observed to be breathing rapidly while stating that he or she is not short of breath. The converse is also true: a patient may be breathing slowly but have dyspnea. Never assume that a patient with a rapid respiratory rate is dyspneic.

It is important for the examiner to inquire when dyspnea occurs and in which position. Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is the sudden onset of shortness of breath occurring at night during sleep. Patients are suddenly seized with an intense strangling sensation. They frantically sit up and, classically, run to the window for “air.” As soon as they assume an upright position, the dyspnea usually improves. Orthopnea is difficulty breathing while lying flat. Patients require two or more pillows to breathe comfortably. Platypnea is a rare symptom of difficulty breathing while sitting up and is relieved by a recumbent position. Trepopnea is a condition in which patients are more comfortable breathing while lying on one side. (Some of the more common causes of positional dyspnea are listed in Table 10-4.) For any patient complaining of dyspnea, ask the following questions:

“How long have you had shortness of breath?”

“Did the shortness of breath occur suddenly?”

“Is the shortness of breath constant?”

“Does the shortness of breath occur with exertion? At rest? Lying flat? Sitting up?”

“What makes the shortness of breath worse? What relieves it?”

“How many level blocks can you walk without becoming short of breath?”

“How many level blocks could you walk 6 months ago?”

“Do you smoke?” If so, “How much? For how long?”

“Have you had any exposure to asbestos? Sandblasting? Pigeon breeding?”

“Have you had any exposure to individuals with tuberculosis?”

“Have you ever lived near the San Joaquin Valley? Midwestern or southeastern United States?”

Table 10–4

Positional Dyspnea

| Type | Possible Causes |

| Orthopnea | Congestive heart failure |

| Mitral valvular disease | |

| Severe asthma (rarely) | |

| Emphysema (rarely) | |

| Chronic bronchitis (rarely) | |

| Neurologic diseases (rarely) | |

| Trepopnea | Congestive heart failure |

| Platypnea | Postpneumonectomy status |

| Neurologic diseases | |

| Cirrhosis (intrapulmonary shunts) | |

| Hypovolemia |

It is essential to try to quantify the dyspnea. Questions such as “How many level blocks can you walk?” provide a framework for exercise tolerance. For example, if the patient answers, “two blocks,” the patient is said to have two-block dyspnea on exertion. The interviewer can then ask, “How many level blocks were you able to walk 6 months ago?” and thus assess approximately the progression of the disease or the efficacy of therapy.

Careful questioning regarding industrial exposure is paramount for any patient with unexplained dyspnea. Examples of further questions regarding occupational and environmental history are discussed in Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions. Exposure to pigeons may result in psittacosis. Outbreaks of coccidioidomycosis have occurred in individuals living in the southwestern United States. Living in the midwestern and southeastern United States has been linked to outbreaks of histoplasmosis.

Wheezing

Wheezing is an abnormally high-pitched noise resulting from a partially obstructed airway. It is usually present during expiration when slight bronchoconstriction occurs. Bronchospasm, mucosal edema, loss of elastic support, and tortuosity of the airways are the usual causes. Asthma causes bronchospasm, which results in the wheezing associated with this condition. Obstruction by intraluminal material, such as aspirated foreign bodies or secretions, is another important cause of wheezing. A well-localized wheeze, unchanged by coughing, may indicate that a bronchus is partially obstructed by a foreign body or tumor. When a patient complains of wheezing, the examiner must determine the following:

“At what age did the wheezing begin?”

“Are there any precipitating factors, such as foods, odors, emotions, animals, and so forth?”

“What usually stops the attack?”

“Have the symptoms worsened over the years?”

“Are there any associated symptoms?”

“Is there a history of nasal polyps?”

“Do you smoke?” If so, “What do you smoke? How much, and for how long?”

An important axiom to remember is that asthma is associated with wheezing, but not all wheezing is asthma.

Do not equate wheezing only with asthma. Although congestive heart failure is usually associated with abnormal breath sounds called crackles (discussed later in this chapter), sometimes there is such severe bronchospasm in heart failure that the main physical finding is a wheeze rather than a crackle.

A decrease in wheezing may result from either an opening of the airway or a progressive closing off of the air passage. A “silent” chest in a patient with an acute asthmatic attack is usually an ominous sign: It indicates worsening of the obstruction.

Cyanosis

Cyanosis is commonly detected by a family member or friend. The subtle bluish discoloration may go completely unnoticed by the patient. Central cyanosis occurs with inadequate gas exchange in the lungs that results in a significant reduction in arterial oxygenation. Primary pulmonary problems or diseases that cause mixed venous blood to bypass the lungs (e.g., intracardiac shunt) are frequently the causative factors. The bluish discoloration is best seen in the mucous membranes of the mouth (e.g., the frenulum) and lips. Peripheral cyanosis results from an excessive extraction of oxygen at the periphery. It is limited to the extremities (e.g., the fingers, toes, nose). Ask the following questions:

“Where is the cyanosis present?”

“How long has the cyanosis been present?”

“Are you aware of any lung problem? Heart problem? Blood problem?”

“What makes the cyanosis worse?”

“Is there associated shortness of breath? Cough? Bleeding?”

Cyanosis from birth is associated with congenital heart lesions. The acute development of cyanosis can occur in severe respiratory disease, especially acute airway obstruction. Peripheral cyanosis results from increased oxygen extraction in states of low cardiac output and is seen in cooler areas of the body such as the nail beds and the outer surfaces of the lips. Peripheral cyanosis disappears as the area is warmed. Cyanosis of the nails and warmth in the hands suggest that the cyanosis is central. Central cyanosis occurs only after the oxygen saturation has fallen to less than 80%. Central cyanosis diffusely involves the skin and mucous membranes and does not disappear with warming of the area. At least 2 to 3 g of unsaturated hemoglobin per 100 mL of blood must be present for the patient to manifest central cyanosis. Exercise worsens central cyanosis because the exercising muscles require an increased extraction of oxygen from the blood. In patients with severe anemia, in whom hemoglobin levels are markedly decreased, cyanosis may not be seen. Clubbing of the nails is seen in association with central cyanosis and significant cardiopulmonary disorders. See Figure 5-12.

Some industrial workers, such as arc welders, inhale toxic levels of nitrous gases that can produce cyanosis by methemoglobinemia. Hereditary methemoglobinemia is a primary hemoglobin abnormality causing congenital cyanosis.

Chest Pain

Chest pain related to pulmonary disease usually results from involvement of the chest wall or parietal pleura. Nerve fibers are abundant in this area. Pleuritic pain is a common symptom of inflammation of the parietal pleura. It is described as a sharp, stabbing pain that is usually felt during inspiration. It may be localized to one side, and the patient may splint1 to avoid the pain. Chapter 11, The Heart, summarizes the important questions to ask a patient complaining of chest pain.

Acute dilatation of the main pulmonary artery may also produce a sensation of dull pressure, often indistinguishable from angina pectoris. This results from nerve endings responding to the stretch on the main pulmonary artery.

Although chest pain occurs in pulmonary disease, chest pain is the cardinal symptom of cardiac disease and is discussed more completely in Chapter 11, The Heart.

Snoring

Snoring is a common complaint. An important problem often associated with heavy snoring is obstructive sleep apnea. Many affected patients are overweight and have a history of excessive daytime sleepiness. A bed partner may describe the patient as at first sleeping quietly; then a transition occurs to louder snoring, followed by a period of cessation of snoring, during which time the patient becomes restless, has gasping motions, and appears to be struggling for breath. This period is terminated by a loud snort, and the sequence may begin again. It is common for patients with sleep apnea to have many of these episodes each night. Refer to Chapter 9, The Oral Cavity and Pharynx, for more information on snoring and sleep apnea.

Other Symptoms

In addition to the main symptoms of pulmonary disease, there are other, less common symptoms. These include the following:

Stridor is a harsh type of noisy breathing and is usually associated with obstruction of a major bronchus that occurs with aspiration. Voice changes can occur with inflammation of the vocal cords or interference with the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Swelling of the ankles is a manifestation of dependent edema, which is associated with right-sided heart failure, renal disease, liver disease, and obstruction of venous flow. As the condition worsens, abnormal accumulations of fluid produce generalized edema, known as anasarca.

Effect of Lung Disease on the Patient

The effect of lung disease on the patient varies greatly with the nature of the ailment, as does the subjective sensation of air hunger. Some patients with lung disease are hardly aware of the dyspnea. The decrease in exercise tolerance is so insidious that these patients may not be aware of any problem. Only when asked to try to quantify the dyspnea do these patients realize their deficiency. In other patients, dyspnea is so rapidly progressive that they experience severe depression. They recognize that little can be done to improve their lung conditions and thus markedly alter their lifestyle. Many become incapacitated and are forced to retire from work. They can no longer experience the slightest exertion without becoming dyspneic.

Often, chronic lung disease develops as a result of occupational hazards. Affected patients may become embittered and hostile. There has been much publicity about occupational exposure, but some industries still provide little protection for their employees.

COPD can be divided into two types: emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Both are characterized by a slowly progressive course, obstruction of airflow, and destruction of the lung parenchyma. Classically, patients with emphysema are the “pink puffers.” They are thin and weak from severe dyspnea associated with little cough or sputum production. The classic “blue bloaters” suffer primarily from bronchitis. They are cyanotic and have a productive cough but are less troubled by dyspnea; they are usually short and stocky. These classic descriptions are interesting, but most patients with COPD have characteristics of both types.

Since ancient times, clinicians have recognized that emotional factors play a role in the onset and maintenance of symptoms in bronchial asthma. Attacks of asthma can be provoked by a range of emotions: fear, anger, anxiety, depression, guilt, frustration, and joy. It is the patient’s attempt to suppress the emotion, rather than the emotion itself, that precipitates the asthmatic attack.

A patient having an asthmatic attack becomes anxious and fearful, which tends to perpetuate the attack. Hyperventilation may contribute to the breathlessness of the frightened patient. Despite being given adequate medical therapy, these patients remain dyspneic. In such patients, it is the anxiety and its causes that require attention. They need continuing medical and psychologic support after an acute attack. As early as the twelfth century, Maimonides recognized that “mere diet and medical treatment cannot fully cure this disorder.”

Asthma in children presents a special problem. Anxiety, underachievement, peer pressure, and noncompliance with medications can exacerbate episodes of asthma. These children are absent from school more often than their nonasthmatic peers, which causes schoolwork to suffer; this creates a vicious cycle. The incidence of emotional disorders is greater than twofold higher in asthmatic school-aged children than in the general population.

Asthma can affect a person’s sexual function both physiologically and psychologically. Asthmatic patients may become more dyspneic as a result of the increased physical demands of sexual intercourse. Bronchospasm may occur, owing to excitement, anxiety, or panic. Anxiety about precipitating an asthmatic attack during sexual intercourse worsens the patient’s dyspnea and sexual performance; another vicious cycle is set into motion. Patients may then tend to avoid sexual intercourse.

Physical Examination

The equipment necessary for the examination of the chest is a stethoscope.

After a general assessment of the patient, the examination of the posterior chest is performed while the patient is still seated. The patient’s arms should be folded in his or her lap. After the examination of the posterior chest is completed, the patient is asked to lie down, and the examination of the anterior chest is begun. During the examination, the examiner should try to imagine the underlying lung areas.

If the patient is a man, his gown should be removed to his waist. If the patient is a woman, the gown should be positioned to prevent unnecessary or embarrassing exposure of the breasts. The examiner should stand facing the patient.

The examination of the anterior and posterior aspects of the chest includes the following:

General Assessment

Inspect the Patient’s Facial Expression

Is the patient in acute distress? Is there nasal flaring or pursed lip breathing? Nasal flaring is the outward motion of the nares during inhalation. This is seen in any condition that causes an increase in the work of breathing. Are there audible signs of breathing, such as stridor and wheezing? These are related to obstruction to airflow. Is cyanosis present?

Inspect the Patient’s Posture

Patients with airway obstructive disease tend to prefer a position in which they can support their arms and fix the muscles of the shoulder and neck to aid in respiration. A common technique used by patients with bronchial obstruction is to clasp the sides of the bed and use the latissimus dorsi muscle to help overcome the increased resistance to outflow during expiration. Patients with orthopnea remain seated or lie on several pillows.

Inspect the Neck

Is the patient’s breathing aided by the action of the accessory muscles? Use of the accessory muscles is one of the earliest signs of airway obstruction. In respiratory distress, the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles contract during inspiration. The accessory muscles assist in ventilation; they raise the clavicle and anterior chest to increase the lung volume and produce an increased negative intrathoracic pressure. This results in retraction of the supraclavicular fossae and intercostal muscles. An upward motion of the clavicle of more than 5 mm during respiration is associated with severe obstructive lung disease.

Inspect the Configuration of the Chest

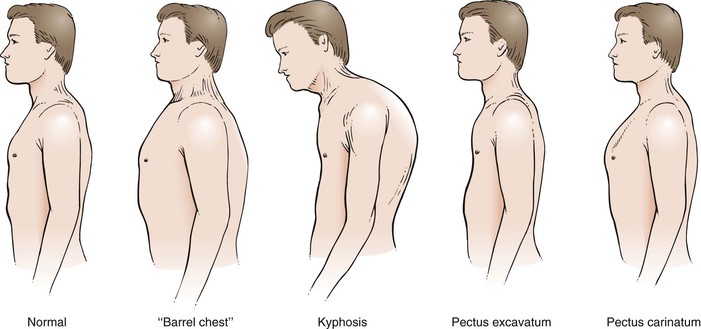

A variety of conditions may interfere with adequate ventilation, and the configuration of the chest may indicate lung disease. An increase in the anteroposterior diameter is seen in advanced COPD. The anteroposterior diameter tends to equal the lateral diameter, and a barrel chest results. The ribs lose their 45-degree angle and become more horizontal. A flail chest is a configuration in which one chest wall moves paradoxically inward during inspiration. This condition is seen with multiple rib fractures. The spinal deformity kyphoscoliosis results in an abnormal anteroposterior diameter and lateral curvature of the spine that severely restricts chest and lung expansion. Figure 10-6 depicts a patient with severe kyphoscoliosis. Pectus excavatum, or “funnel chest,” is a depression of the sternum that produces a restrictive lung problem only if the depression is marked. Patients with pectus excavatum may have abnormalities of the mitral valve, especially mitral valve prolapse. Figure 10-7 depicts a patient with pectus excavatum. Pectus carinatum, or pigeon breast, which results from an anterior protrusion of the sternum, is a common deformity but does not compromise ventilation. Figure 10-8 depicts a patient with pectus carinatum. Notice the prominent sternal ridge and the ribs slanting steeply away on either side. Figure 10-9 illustrates the various configurations of the chest.

Figure 10–6 Severe kyphoscoliosis.

Figure 10–7 Pectus excavatum.

Figure 10–8 Pectus carinatum.

Figure 10–9 Common chest configurations.

Assess the Respiratory Rate and Pattern

When assessing respiratory rate, never ask the patient to breathe “normally.” Individuals voluntarily change their breathing patterns and rates once they are aware that respiration is being assessed. A better way is, after taking the radial pulse, to direct your eyes to the patient’s chest and evaluate respirations while still holding the patient’s wrist. The patient is unaware that you are no longer taking the pulse, and voluntary changes in breathing rate will not occur. Counting the number of respirations in a 30-second period and multiplying that number by two provides an accurate respiratory rate.

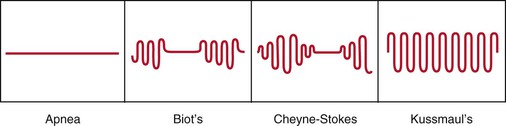

The normal adult takes approximately 10 to 14 breaths a minute. Bradypnea is an abnormal slowing of respiration; tachypnea is an abnormal increase. Apnea is the temporary cessation of breathing. Hyperpnea is an increased depth of breathing, usually associated with metabolic acidosis. It is also known as Kussmaul‘s breathing. There are many types of abnormal breathing patterns. Figure 10-10 illustrates and lists the more common types of abnormal breathing.

Figure 10–10 Patterns of abnormal breathing.

Inspect the Hands

Is clubbing of the fingernails present? The technique for evaluating clubbing is described in Chapter 5, The Skin. The earliest finding of clubbing is loss of the angle between the nail and the terminal phalanx. Look at Figure 5-12, in which a normal index fingernail is compared with a severely clubbed index fingernail of a patient with bronchogenic carcinoma.

Clubbing has been associated with a number of clinical disorders, such as the following:

The pathogenesis of clubbing is unclear. In many conditions, however, arterial desaturation occurs. This, in some way, may be the underlying problem. In some individuals, clubbing may be inherited without any pathologic process.

The Posterior Chest

Move behind the patient to examine the posterior chest.

Palpation

Palpation is used to assess the following:

Palpate for Tenderness

With your fingers, firmly palpate any chest areas where tenderness is experienced by the patient. A complaint of “chest pain” may be related only to local musculoskeletal disease and not to disease of the heart or lungs. Be meticulous in assessing for areas of tenderness.

Evaluate Posterior Chest Excursion

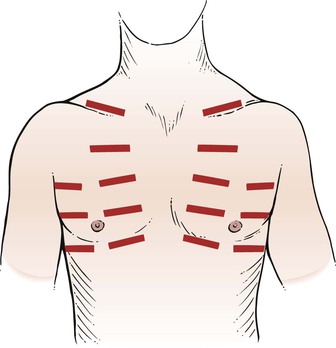

The examiner can determine the degree of symmetry of chest excursion by placing his or her hands flat against the patient’s back with the thumbs parallel to the midline at approximately the level of the tenth ribs and pulling the underlying skin slightly toward the midline. The patient is asked to inhale deeply, and the movement of the examiner’s hands is noted. The hand movement should be symmetric. Localized pulmonary disease may cause one side of the chest to move less than the opposite side. The placement of the examiner’s hands is shown in Figure 10-11.

Evaluate Tactile Fremitus

Speech creates vibrations that can be heard when the examiner listens to the chest and lungs. These vibrations are termed vocal fremitus. When the examiner palpates the patient’s chest wall while the patient is speaking, these vibrations can be felt and are termed tactile fremitus. Sound is conducted from the larynx through the bronchial tree to the lung parenchyma and the chest wall. Tactile fremitus provides useful information about the density of the underlying lung tissue and chest cavity. Conditions that increase the density of the lung and make it more solid, such as consolidation, increase the transmission of tactile fremitus. Clinical states that decrease the transmission of these sound waves result in reduced tactile fremitus. If there is excess fat tissue on the chest, air or fluid in the chest cavity, or overexpansion of the lung, tactile fremitus is diminished.

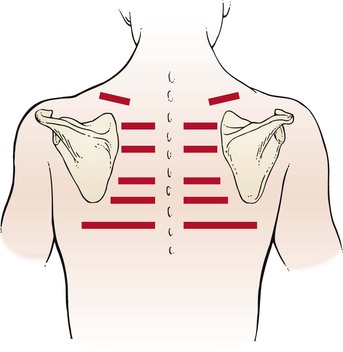

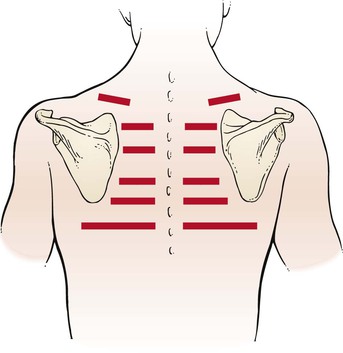

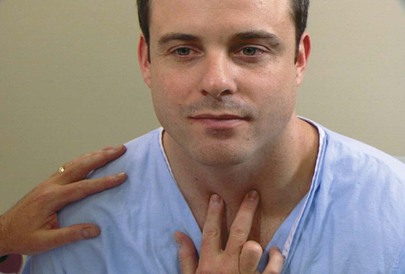

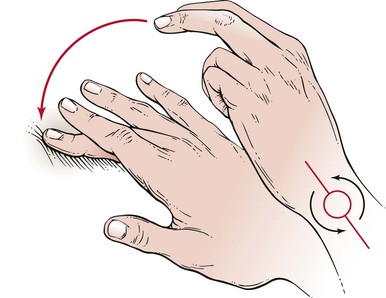

Tactile fremitus can be evaluated in two ways. In the first technique, the examiner places the ulnar side of his or her right hand against the patient’s chest wall, as demonstrated in Figure 10-12, and asks the patient to say, “Ninety-nine.” Tactile fremitus is evaluated, and the examiner’s hand is moved to the corresponding position on the other side. Tactile fremitus on the opposite side is then evaluated and compared. By moving the hand from side to side and from top to bottom, the examiner can detect differences in the transmission of the sound to the chest wall. “Ninety-nine”2 is one of the phrases used in English because it causes good vibratory tones. Alternately, the patient could be asked to say, “one, two, three,” or “eee.” If the patient speaks either louder or deeper, the tactile sensation is enhanced. Tactile fremitus should be evaluated in the six locations illustrated in Figure 10-13.

Figure 10–12 Technique for evaluating tactile fremitus.

The other method of evaluating tactile fremitus is to use the fingertips instead of the ulnar side of the hand. The same side-to-side and top-to-bottom positions illustrated in Figure 10-13 are used. The evaluation of tactile fremitus should be performed with only one of these techniques. The examiner should try both methods initially to determine which one is preferable.

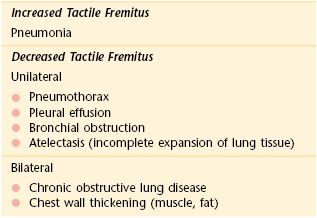

Table 10-5 lists some of the important pathologic causes of changes in tactile fremitus.

Percussion

Percussion refers to tapping on a surface to determine the underlying structure. It is similar to a radar or echo detection system. Tapping on the chest wall creates vibrations that are transmitted to the underlying tissue, reflected back, and picked up by the examiner’s tactile and auditory senses. The sound heard and the tactile sensation felt depend on the air-tissue ratio. The vibrations initiated by percussion of the chest enable the examiner to evaluate the lung tissue to a depth of only 5 to 6 cm, but percussion is valuable because many changes in the air-tissue ratio are readily apparent.

Percussion over a solid organ, such as the liver, produces a dull, low-amplitude, short-duration note without resonance. Percussion over a structure containing air within a tissue, such as the lung, produces a resonant, higher amplitude, lower pitched note. Percussion over a hollow air-containing structure, such as the stomach, produces a tympanic, high-pitched, hollow-quality note. Percussion over a large muscle mass, such as the thigh, produces a flat, high-pitched note.

Normally, in the chest, dullness over the heart and resonance over the lung fields are heard and felt. As the lungs fill with fluid and become denser, as in pneumonia, resonance is replaced by dullness. The term hyperresonance has been applied to the percussion note obtained from a lung with decreased density, such as that found in emphysema. Hyperresonance is a low-pitched, hollow-quality, sustained resonant note bordering on tympany.

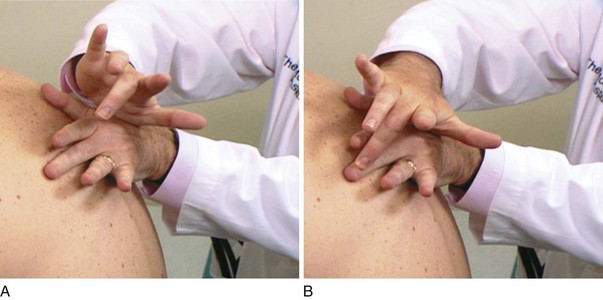

In percussion of the chest, the examiner places the middle finger of one hand firmly against the patient’s chest wall, parallel to the ribs in an interspace, with the palm and other fingers held off the chest. The tip of the right middle finger of the other hand strikes a quick, sharp blow to the terminal phalanx of the left finger on the chest wall. The motion of the striking finger should come from the wrist and not from the elbow. Paddleball players use this motion naturally, whereas tennis players must learn to concentrate on using this wrist motion. The technique of percussion is diagrammed in Figure 10-14 and demonstrated in Figure 10-15.

Figure 10–14 Technique of percussion.

Figure 10–15 Percussion. A, Position of the right hand ready to percuss. B, Location of the fingers after striking. Notice that the motion is from the wrist.

Try percussion on yourself. Percuss over your right lung (resonant), stomach (tympanic), liver (dull), and thigh (flat).

Percuss the Posterior Chest

The sites on the posterior chest for percussion are above, between, and below the scapulae in the intercostal spaces, as diagrammed in Figure 10-16. The scapulae themselves are not percussed. The examiner should start at the top and work downward, proceeding from side to side, comparing one side with the other.

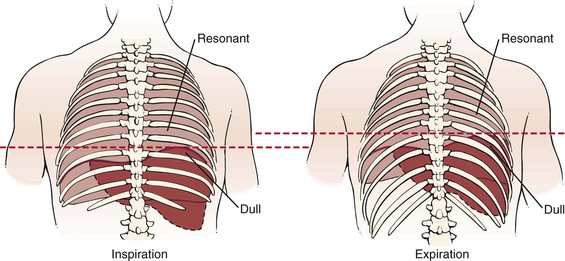

Evaluate Diaphragmatic Movement

Percussion is also used to detect diaphragmatic movement. The patient is asked to take a deep breath and hold it. Percussion at the right lung base helps determine the lowest area of resonance, which represents the lowest level of the diaphragm. Below this level is dullness from the liver. The patient is then instructed to exhale as much as possible, and the percussion is repeated. With expiration, the lung contracts, the liver moves up, and the same area becomes dull; that is, the level of dullness moves upward. The difference between the inspiration and expiration levels represents diaphragmatic motion, which is normally 4 to 5 cm. In patients with emphysema, the motion is reduced. In patients with a phrenic nerve palsy, diaphragmatic motion is absent. This test is illustrated in Figure 10-17.

Figure 10–17 Technique for evaluating diaphragmatic motion. During inspiration (left), percussion in the right seventh posterior interspace at the midscapular line would be resonant as a result of the presence of the underlying lung. During expiration (right), the liver and diaphragm move up. Percussion in the same area would now be dull, owing to the presence of the underlying liver.

Auscultation

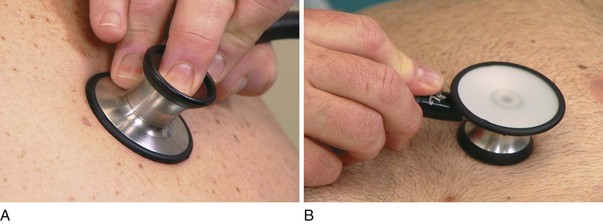

Auscultation is the technique of listening for sounds produced in the body. Auscultation of the chest is used to identify lung sounds. The stethoscope usually has two heads: the bell and the diaphragm. The bell is used to detect low-pitched sounds, and the diaphragm is better at detecting higher pitched sounds. The bell must be applied loosely to the skin; if it is pressed too tightly, the skin acts as a diaphragm, and the lower pitched sounds are filtered out. In contrast, the diaphragm is applied firmly to the skin. In very cachectic individuals, the bell may be more useful because the protruding ribs in these patients make placement of the diaphragm difficult. The correct placements of the heads of the stethoscope are demonstrated in Figure 10-18.

Figure 10–18 Placement of stethoscope heads. A, Correct placement of the diaphragm. Notice that the head is applied tightly to the skin. B, Placement of the bell. Notice that the bell is applied lightly to the skin.

It is never acceptable to listen through clothing. The bell or the diaphragm of the stethoscope must always be in contact with the skin.

Types of Breath Sounds

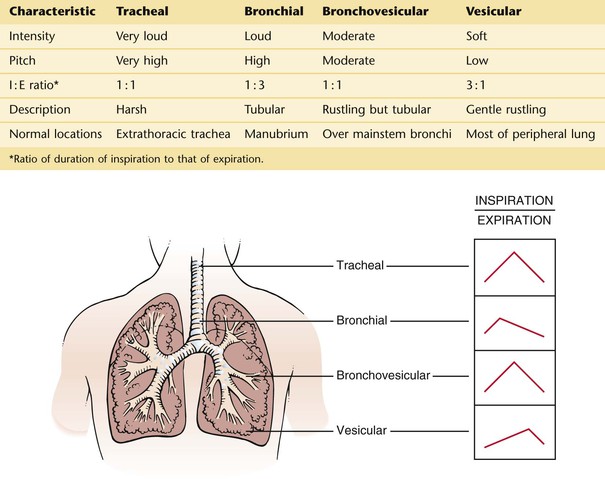

Breath sounds are heard over most of the lung fields. They consist of an inspiratory phase followed by an expiratory phase. There are four types of normal breath sounds:

Tracheal breath sounds are harsh, loud, high-pitched sounds heard over the extrathoracic portion of the trachea. The inspiratory and expiratory components are approximately equal in length. Although these sounds are always heard when the examiner listens over the trachea, they are rarely evaluated because they do not represent any clinical lung problems.

Bronchial breath sounds are loud and high-pitched and sound like air rushing through a tube. The expiratory component is louder and longer than the inspiratory component. These sounds are normally heard when the examiner listens over the manubrium. A definite pause is heard between the two phases.

Bronchovesicular breath sounds are a mixture of bronchial and vesicular sounds. The inspiratory and expiratory components are equal in length. They are normally heard only in the first and second interspaces anteriorly and between the scapulae posteriorly. This is the area overlying the carina and mainstem bronchi.

Vesicular breath sounds are the soft, low-pitched sounds heard over most of the lung fields. The inspiratory component is much longer than the expiratory component, which is also much softer and frequently inaudible.

The four types of breath sounds are illustrated and summarized in Figure 10-19.

Figure 10–19 Characteristics of breath sounds.

Auscultate the Posterior Chest

Auscultation should be performed in a quiet environment. The patient is asked to breathe in and out through the mouth. The examiner should concentrate first on the length of inspiration and then on expiration. Very soft breath sounds are referred to as distant. Distant breath sounds are commonly found in patients with hyperinflated lungs, as in emphysema.

The examination should proceed from side to side and from top to bottom, comparing one side with the other. The positions are illustrated in Figure 10-16. Because most breath sounds are high-pitched, the diaphragm is used to evaluate lung sounds.

The Anterior Chest

The examiner should now move in front of the patient. The first part of the examination of the anterior chest is performed with the patient seated, after which the patient is asked to lie down.

Evaluate the Position of the Trachea

The examiner can determine the position of the trachea by placing his or her right index finger in the patient’s suprasternal notch and moving slightly lateral to feel the location of the trachea. The examiner repeats this technique, moving the finger from the suprasternal notch to the other side. The space between the trachea and the clavicle should be equal on each side. A shift of the mediastinum can displace the trachea to one side. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 10-20.

Look at the patient pictured in Figure 10-21. Notice that the trachea is markedly displaced to the right in this very cachectic woman. The diagnosis of a mass either pushing or pulling the trachea to the right is suggested.

Now ask the patient to lie on his or her back for the rest of the examination of the anterior chest. The patient’s arms are at the sides. If the patient is a woman, either have her elevate her breasts herself or displace them yourself as necessary during palpation, percussion, and auscultation. These examinations should not be performed over breast tissue.

Evaluate Tactile Fremitus

Tactile fremitus is assessed in the supraclavicular fossae and in alternate anterior interspaces, beginning at the clavicle. The techniques for evaluating tactile fremitus have already been discussed. Proceed from the supraclavicular fossae downward, comparing one side with the other.

Percuss the Anterior Chest

Percussion of the anterior chest includes the supraclavicular fossae, the axillae, and the anterior interspaces, as illustrated in Figure 10-22. The percussion note on one side is always compared with that elicited in the corresponding position on the other side. Dullness may be noted in the third to fifth intercostal spaces to the left of the sternum, which is related to the presence of the heart. Percuss high in the axilla because the upper lobes are best evaluated at these positions. Axillary percussion is sometimes easier to perform while the patient is sitting.

Auscultate the Anterior Chest

Auscultation of the anterior chest is performed in the supraclavicular fossae, the axillae, and the anterior chest interspaces, as illustrated in Figure 10-22. The techniques of auscultation have already been discussed. The breath sounds of one side are compared with the breath sounds heard in the corresponding position on the other side.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

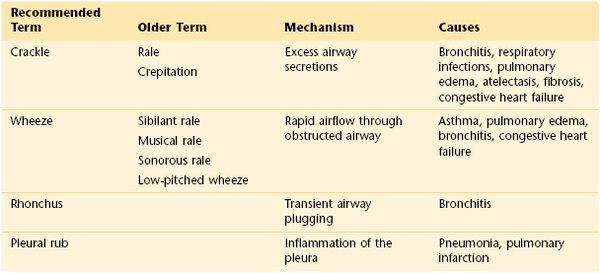

In addition to the normal breath sounds discussed, other lung sounds may be produced in abnormal clinical states. These abnormal sounds heard during auscultation are called adventitious sounds. Adventitious sounds include the following:

Crackles are short, discontinuous, nonmusical sounds heard mostly during inspiration. Also known as rales or crepitation, crackles are caused by the opening of collapsed distal airways and alveoli. A sudden equalization of pressure seems to result in a crackle. Coarser crackles are related to larger airways. Crackles are likened to the sound made by rubbing hair next to the ear or the sound made when hook-and-loop patches are pulled apart. They may be described as early or late, depending on when they are heard during inspiration. The timing of common inspiratory crackles is summarized in Table 10-6. The most common causes of crackles are pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary fibrosis.

Table 10–6

Timing of Common Inspiratory Crackles

| Disease | Early Crackle | Late Crackle |

| Congestive heart failure | Very common | Common |

| Obstructive lung disease | Present | Absent |

| Interstitial fibrosis | Absent | Present |

| Pneumonia | Absent | Present |

Wheezes are continuous, musical, high-pitched sounds heard mostly during expiration. They are produced by airflow through narrowed bronchi. This narrowing may be caused by swelling, secretions, spasm, tumor, or foreign body. Wheezes are commonly associated with the bronchospasm of asthma.

Rhonchi are lower pitched, more sonorous lung sounds. They are believed to be more common with transient mucous plugging and poor movement of airway secretions.

A pleural rub is a grating sound produced by motion of the pleura, which is impeded by frictional resistance. It is best heard at the end of inspiration and at the beginning of expiration. The sound of a pleural rub is like the sound of creaking leather. Pleural rubs are heard when pleural surfaces are roughened or thickened by inflammatory or neoplastic cells or by fibrin deposits.

All the adventitious sounds should be described with regard to their location, timing, and intensity.

There is much confusion regarding the terminology of adventitious sounds. Table 10-7 summarizes the adventitious sounds.

On occasion, breath sounds are transmitted abnormally. This may result in auscultatory changes known by the following terms:

Egophony (egobronchophony) is said to be present when the spoken word heard through the lungs is increased in intensity and takes on a nasal or bleating quality. The patient is asked to say “eeee” while the examiner listens to an area in which consolidation is suspected. If egophony is present, the “eeee” will be heard as “aaaah” This “e-to-a” change is seen in consolidation of lung tissue. The area of compressed lung above a pleural effusion often produces egophony.

Whispered pectoriloquy is the term for the intensification of the whispered word heard in the presence of consolidation of the lung. The patient is instructed to whisper, “one-two-three” while the examiner listens to the area suspected of having consolidation. Normally, whispering produces high-pitched sounds that tend to be filtered out by the lungs. Little or nothing may be heard when the examiner listens to a normal chest. However, if consolidation is present, the transmission of the spoken words is increased, and the words are clearly heard.

Bronchophony is the increased transmission of spoken words heard in the presence of consolidation of the lungs. The patient is asked to say, “ninety-nine” while the examiner listens to the chest. If bronchophony is present, the words are transmitted more loudly than is normal.

One of the most important principles concerning the examination of the chest is to correlate the findings of percussion, palpation, and auscultation. Dullness, crackles, increased breath sounds, and increased tactile fremitus are suggestive of consolidation. Dullness, decreased breath sounds, and decreased tactile fremitus are suggestive of a pleural effusion.

Many physical signs are associated with obstructive lung disease. These include impaired breath sounds, barrel chest, decreased chest expansion, impaired cardiac dullness, use of accessory muscles, absent cardiac impulse, cyanosis, and diminished diaphragmatic excursion. Although all these are important physical findings, the first three have the greatest intrinsic value as diagnostic tools.

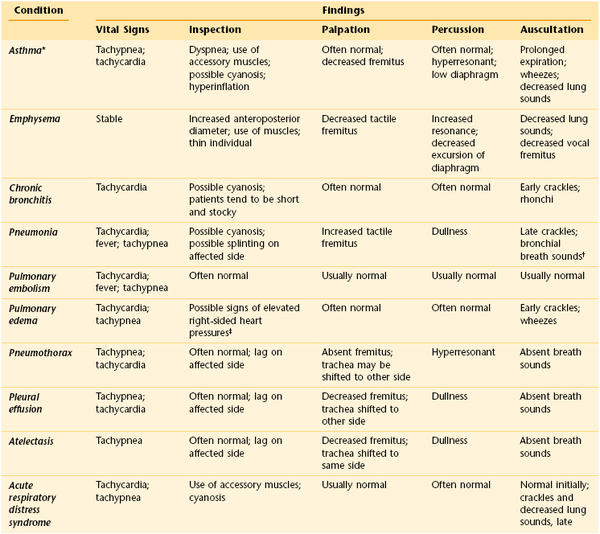

Table 10-8 lists some of the common causes of dyspnea and their associated symptoms. Table 10-9 summarizes some important manifestations of common pulmonary conditions.

Table 10–8

Common Conditions Associated with Dyspnea

| Condition | Dyspnea | Other Symptoms |

| Asthma | Episodic; symptom free between attacks | Wheezing, chest pain, productive cough |

| Pulmonary edema | Abrupt | Tachypnea, cough, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea with chronic state |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | Progressive | Tachypnea, dry cough |

| Pneumonia | Exertional, insidious onset | Productive cough, pleuritic pain |

| Pneumothorax | Sudden, moderate to severe | Sudden pleuritic pain |

| Emphysema | Insidious onset, severe | Cough as disease progresses |

| Chronic bronchitis | As disease progresses and with infection | Chronic, productive cough |

| Obesity | Exertional |

Table 10–9

Differentiation of Common Pulmonary Conditions

* The physical findings in asthma are often not reliable in predicting its severity.

† Bronchophony, whispered pectoriloquy, and egophony are also often present.

‡ Elevated jugular venous distention, pedal edema, and hepatomegaly.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;7(5):423.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2011.

Benowitz NL. Nicotine addition. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2295.

Caples SM, Gami AS, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:187.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and tobacco use. Fact sheet. Health effects of cigarette smoking. Updated March 2011. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm [Accessed January 29, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis. Updated October 2011. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/tb/ [Accessed January 30, 2013] .

Chung F, et al. Validation of the Berlin questionnaire and American Society of Anesthesiologists checklist as screening tools for obstructive sleep apnea in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):822.

Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371(9621):1364.

DevCan. Probability of developing or dying of cancer software, version 5.1. Statistical Research and Applications Branch. National Cancer Institute; 2003 http://srab.cancer.gov/devcan.

Drager LF, et al. Characteristics and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(8):1135.

Espey DK, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007;110:2119.

Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010. [Available at] http://www.goldcopd.org/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Hays JT, Ebbert JO. Varenicline for tobacco dependence. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2018.

Konstantinides S. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2804.

Littner M. In the clinic: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:ITC3-1.

Millman RP. Do you ever take a sleep history? Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:535.

Nathanson E, et al. MDR tuberculosis—critical steps for prevention and control. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1050.

Neiwoehner DR. Outpatient management of severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1407.

Netzer NC, et al. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485.

Office of the Surgeon General. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD; 2010 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/tobaccosmoke/index.html.

Panettieri RA. In the clinic: asthma. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:ITC6-1.

Ranney I, et al. Systematic review: smoking cessation intervention strategies for adults in special populations. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:506.

Ritz HJ. Pinning down the cause of chronic cough. JAAPA. 2004;17:27.

Sargent JD, DiFranza JR. Tobacco control for clinicians who treat adolescents. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:102.

Somers VK, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. An American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiology. 2008;52:686.

Stubbing DG, Mathur PN, Roberts RS. Some physical signs in patients with chronic airway obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:549.

Weinberger SE, Cockrill BA, Mandel J. Principles of pulmonary medicine. ed 5. Saunders/Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2008.

Wenzel RP, Fowler AA. Acute bronchitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2125.

Wilson J. In the clinic: smoking cessation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:ITC2-1.

Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus SE. Does this patient have a pleural effusion? JAMA. 2009;301:309.

1 Splinting means making the chest muscles rigid to avoid motion of that part of the chest.

2 Saying “ninety-nine” is derived from the German neun und neunzig meaning “99.” These German words are very nasal and create a very vibratory sensation. Other languages may use other words or sounds to evaluate tactile fremitus.