Chapter 12. The changing dynamic of policy and practice in Australian healthcare

Christine Jorm, Margaret Banks and Sara Twohill

Introduction

Managing clinical work to achieve the best possible quality of care requires systems to be established and information to be shared. Policy is a mechanism through which these ends can be realised, and while often defined in a formal sense as a blueprint of intentions, health policy can also be described informally as the ‘courses of action that affect that set of institutions, organisations, services and funding arrangements’ in the healthcare system (Palmer & Short 2000:2). Recent policy in Australia has been directed to health system reform, but ‘good policy intentions’ are often hampered by complex funding and governance arrangements, specifically, in the case of Australia, by the politics of federalism where both state and federal levels of government share responsibility for health services. The duplication and division that shared responsibility brings impedes reform (Willis et al 2005), and the funding provided by the Commonwealth to state public hospitals via the Australian Healthcare Agreements (negotiated between both levels of government) provides the Commonwealth with opportunities to influence the shape and direction of reform. There is no easy ‘solution’ to the federal–state issue, although redesign efforts are occurring at multiple levels in the system to better link funding models with incentives for improved outcomes (Swerissen & Duckett 2002). The difficulty remains in determining which outcomes are chosen, how they are measured and the incentives and sanctions offered.

Health reform is made more complex by a range of other structural factors, including a substantial private sector that accounted for 41% of hospital beds in 2003–04, and an increasing emphasis on the responsibility of individuals for their own healthcare needs. There are the pressures from the professions, specifically the medical profession about their changing place in the system, and from consumers about the level and standard of service provided. Together with the life and death nature of healthcare decisions, these complexities in the system all impact to make health a fraught policy arena and, within this contested environment, the concern that health policy may do harm (Spitz & Abramson 2005) is a significant challenge for policymakers. Examining health policy from the recent past can illuminate important modern practices and provide clues for the future. In this chapter we examine two ‘small’ policy directives and conclude that small policy directives struggle to guide and control care, just as large policy initiatives do.

Health Policy 1990

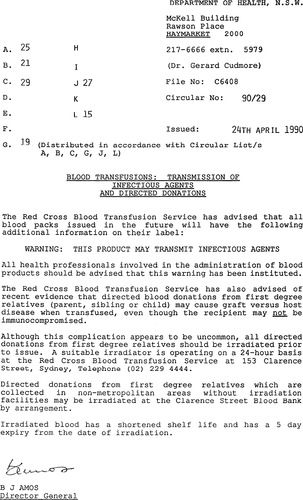

For the purpose of our discussion, two 1990 policy circulars from New South Wales are reproduced and appended to this chapter: Circular 90/29 (Appendix 1) issued in April 1990 and Circular 90/122 (Appendix 2) issued in December 1990. Both are representative of policy issued by Australian state and territory health departments at that time. They are examples of ‘control and command’ statements that presume the organisationally shared understanding of authority, direction and discipline that is a hallmark of classical management theory. These policies were issued to the public health system in the form of a paper-based notification intended to guide the actions of health practitioners and managers.

Circular 90/29 is brief and deals with two separate issues: first, the commencement of labelling of blood units with a warning of possible infectious transmission; and second, the possibility of directed donations of blood from first-degree relatives causing graft versus host disease, and a central office directive that these blood donations be irradiated in future. These issues are separate but related. The discovery of the transmission of HIV (and other infections such as hepatitis C) via blood transfusion resulted in an increased demand for directed donation. This relationship is not made explicit in the document and multiple ambiguities are encoded into this circular: Which infections might be in the blood and undetected by screening? What data would help doctors and patients decide about the relative risks and benefit of transfusion if the blood could be infected? Are directed donations to be discouraged or encouraged? How are arrangements made for blood irradiation? Who is the label for? Is it to ‘protect’ the blood bank? The label warns, but doesn’t inform, nor does the circular.

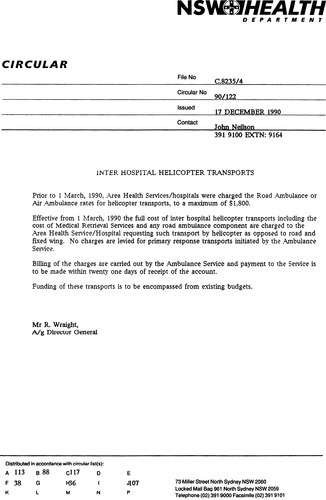

Circular 90/122 is even briefer. Published later in 1990 it has acquired a letterhead and logo, increasing the appearance of legitimacy. It refers to a new procedure for billing for inter-hospital air transports. A previous fixed charge is to be replaced by full cost recovery. This is to be met within existing budgets. No reasons are given for the directive. It appears to be an attempt to reduce the demand for, and therefore the cost of air transport by introducing a user-pays mechanism. It is ambiguous in terms of the potential size of full cost recovery charges, and the implications for regional areas could be significant, but there is no suggestion of special budget consideration. There is no information about how clinical appropriateness of air transport might be assessed.

The circulars detail the authors’ contact details and file references available within central office. While the files may have contained information on the circular development, including the issues that precipitated the development of the policy statement (and possibly the evidence base and development methodology), this information does not appear on the circular. Policy statements at this time rarely referenced published literature or evidence, and it was infrequent that evidence informed their development. The methodology used to develop such a circular varied and included brief stakeholder consultation through to central composition by a single author.

Policy papers in 1990 needed to be printed, generally off site, and mailed to recipients in health services from the central health department in accordance with a pre-determined distribution list. Inclusion, or indeed exclusion, from the distribution list was determined by the policy officer. Their level of understanding of the operations of health services varied, therefore distribution could exclude groups vital to the policy’s implementation. For Circular 90/29 the print run was 136 copies and these were distributed to directors within the health department (25 copies), public health units (21 copies), health services (29 copies), health professional associations and related organisations, which would have included the 12 medical colleges (19 copies), public hospitals (27 copies) and private hospitals and day procedure centres (15 copies). Further distribution was reliant on these organisations having effective dissemination mechanisms.

The size and fragmentation of the private hospital sector, which at that time consisted of over 33% of available hospital beds (National Health Strategy Working Group 1991), meant this sector was unlikely to consistently receive new policy directives. Copies could be accessed directly from the health department if it was known they existed. The system did not have a reliable mechanism for dissemination of circulars to the 18,000 doctors registered in NSW in 1990 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2001) nor to the approximately 30% of these doctors practising in a specialty area where they were likely to order and administer blood.

When viewed, the documents look ancient (a manual typewriter has been used) although they are comparatively recent. We ask what might these directives look like if they were developed now?

Health policy today

Outlined in Box 12.1 are the elements that would be expected to be taken into account when health policy is being formulated today.

Box 12.1

A policy directive developed today would be expected to contain the following elements:

▪ definition of the problem in terms of service provision for clinical stakeholders e.g. ‘health services have had n instances of this issue, which has had x effects on patient outcome (e.g. four deaths) and resulted in the following resource requirements’

▪ detailed reference to the current evidence

▪ a methodology – the process of consultation and development for the policy would be described e.g. a reference group consisting of participants/representatives of a number of specified groups and the outcome of their deliberations

▪ consideration of risks of implementation

▪ specification of expectations around implementation, resourcing and standardisation, e.g.

▪ state-based standardisation of a process and protocol

▪ quarterly reporting against specified indicators

▪ to be funded either within existing budget, via seeding funding or new recurrent program funding

▪ identification of whose responsibility implementation was – if it was sufficiently high level it would be included in managers’ and practitioners’ performance contracts (e.g. that of the blood bank director for a health area)

▪ links to multiple other relevant policy documents

▪ often inclusion of implementation tools, mechanisms for monitoring, and at times evaluation requirements, e.g. the safety and quality manager’s tool kit, use of the state-wide incident monitoring system.

The boxed elements reflect a number of significant developments in Australian health policy in the 17 years since the 1990 documents were created. We highlight four:

1. explicit use of best available evidence

2. significant participation by stakeholders

3. improved accessibility of information

4. introduction of accountability mechanisms.

Each element seems both compelling and essential, indeed a clear improvement over earlier policy processes. Yet when we explore them, their circumstances are complex, their value is contested and the quantity and quality of evidence supporting the benefits of the changes is variable. We discuss each element in turn, examining the current versions of exemplar policy circulars before moving on to the fourth element, accountability mechanisms.

Elements in health policy development and implementation

Explicit use of best available evidence

Policy statements in 1990 rarely if ever referenced published literature or evidence and indeed evidence infrequently informed circular development. Circular 90/29 existed as policy until it was superseded by Circular 92 issued in 2002 – well behind the systems and technology that addressed safety and quality assurance issues (although more likely in a clinical domain).

The term evidence-based medicine emerged less than 20 years ago and is no longer the province of clinical practice alone, with public health practice and policymaking increasingly looking to evidence to support effective health policy development and implementation (Sheldon 2005, Shortell et al 2007). As the healthcare sector becomes inherently more complex, expensive and demanding of greater attention to safety and quality, there is pressure to apply evidence to practice. Yet numerous barriers to its application exist (Canadian Heath Services Research Foundation 2007) and evidence informs policy to a lesser degree than might be expected. As an example, when issuing advice in areas where evidence is available, the World Health Organization rarely uses systematic reviews to inform this advice, relying on expert consensus (Oxman et al 2007).

The influential role that research should play within health policy is hard to dispute. Research has the potential to strengthen and improve healthcare systems when used as the basis for policy decisions. Nonetheless, policymakers presently view research and the evidence base that it produces as limited and problematic. There is a real need for systematic, rigorous and global methods for identifying, interpreting and applying evidence (Dobrow et al 2006). While research in the areas of dissemination and implementation of research into clinical practice is increasing in frequency, there is still a paucity of research into the effectiveness of interventions intended to improve the delivery of care. For instance, despite the sizeable investments made in patient safety, there is little evidence to support links between organisational factors in healthcare, medical errors and patient safety (Hoff et al 2004). Quality improvement strategies also lack a strong evidence base (Shojania & Grimshaw 2005) and there is a deficiency in quality scientific evidence produced through appropriate clinical trials (Tunis et al 2007), for instance for the appropriate use of medications.

Two major arguments have been advanced for this research policy gap: the differing nature of policy and research, and communication challenges in the relationship between researchers and policymakers. We briefly discuss each in turn.

The differing nature of policy and research – compromise versus clarity

If policymaking is to establish agreement between competing claims, this can only be done via compromise (Booth 1988). This agreement may be general and ambiguous, enabling the resulting policy to be flexible in scope and thus more likely to being open to interpretations (as was our exemplar 1990 blood policy). Policy derived from this methodology is adaptable to varied aims and interests and therefore more likely to be accepted.

On the flipside, research is precise in its attempt to provide clarity to inform policy decisions. It does this by taking a number of variables and examining them in a controlled and systematic manner but ‘rarely provides the breadth of vision policymakers require’ (Booth 1988:230). Obtaining an increased understanding of an issue may increase the difficulty and challenge in arriving at an agreed policy decision (especially where experience and opinion are major influences upon health policy development) (Bowen et al 2005). Hence policy and research derive from very different streams of thinking and methodological frameworks. The fluid and ever-evolving environment in which policy is created is a challenge for researchers. The appropriate entry points for evidence-based research into a policy process are rarely controlled, and they are not the same in all instances. Evidence rarely enters into the genesis of a policy proposal because there is a lack of empirical evidence outlining the best methods for effective knowledge transfer into the policy domain (Almeida & Bascolo 2006). There are also apparent or real inadequacies in the timeliness, quality and relevance of research (Innvaer et al 2002). Thus the current utilisation of research in both policy and practice is subtle and indirect.

Relationship between researchers and policymakers – communication challenges

Another theory contends that a lack of communication between researchers and policymakers is the major reason for the policy research gap (Meyer et al 2006). The ‘two communities’ theory maintains that research and policy players are two factions unable to realise the perspectives and realities of one another’s sphere (Innvaer et al 2002). Moreover, with communication lines weak, any endeavour to ‘pair up’ these spheres remains a significant challenge in part because of an absence of personal contact between key players within these domains and because of their mistrust (Meyer et al 2006). Other critics simply advocate the use of ‘[policy] user-friendly formats’ (Laupacis & Straus 2007) for research reviews. By this is meant that research should be brief and focused on validity, applicability and implementation.

A further concern stems from the recently developed pejorative phrase ‘policy-based evidence making’ (House of Commons Science and Technology Committee 2006:para 89) referring to government use or commissioning of research that supports an already-determined policy approach. Doctors in the UK, for example, disbelieve that the National Institute of Clinical Evidence (NICE), the organisation responsible for developing national guidelines, acts independently; 85% of UK doctors state that they would ignore NICE guidance if they thought it ‘was wrong’ – presumably based on the perception that tainted or biased evidence was used (McLoughlin & Leatherman 2003). Consequently, Culyer & Lomas (2006) advocate for transparent deliberative processes allowing policymakers to develop ‘evidence-informed’ decisions. While this might seem an ideal solution, NICE is considered an exemplar of deliberative processes (Culyer & Lomas 2006) but it is still not always considered credible (Milewa 2006).

In summary, while it is easy to suggest that closing the current gap between research and policy is essential for effective health policy development, there are barriers. Research and policy are two very different entities that struggle to align. A number of reasons may account for this difference: there is an overall paucity of policy relevant research; research is often considered to fail policymakers in its appropriateness and timeliness; and there is a lack of mechanisms to appropriately review, disseminate and implement research.

Significant participation by stakeholders

In Australia in 1990 few substantial stakeholder structures existed and the roles and expectations for stakeholders in the policymaking process were ill defined: the current peak national consumer body, the Consumers Health Forum of Australia, had only been founded in 1987; the Commonwealth Department of Health established the Australian General Practice Network and the National Rural Health Alliance in late 1992.

In the absence of defined structures, policymakers met with individuals or representatives of very small groups. Engaging in a process of multiple negotiations with stakeholders was thus impractical, time consuming and expensive. Not surprisingly, the policymaker assumed a position of authority, justified from the perspective that policy legitimacy derived from its enactment by a professional bureaucracy accountable to an elected government (Nagel 2006). The published documents reflect this sense of the policymaker ‘knowing best’. Stakeholders were often brought into the process late, such as at ‘final draft’ stage, and Harvey (1991:14) commented that to establish an efficient and effective healthcare system ‘the three rules are: (1) find out what works; (2) choose what to do – after considering what value is obtained for each additional dollar spent;(3) make sure it happens’. This simple process formulation did not reflect the need for stakeholder engagement or its value.

In the case of the 1990 circular concerning transfusion practice, it is not known who might have been involved in the development of this directive. Such a directive now would involve haematologists, the blood bank, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), medical managers, medical colleges, associations and foundations, accreditation bodies, nurses, doctors and consumers. Extensive discussion would be expected with consumers about directed donations (including issues of patient and family choice and rights) and about how to appropriately involve patients in the discussion about newly recognised risks of blood transfusions. Educational material for patients would be developed during the process.

Modern policy practice sees stakeholder consultation as part of the enactment of policy (see Box 12.2). The multiple expectations of the stakeholder process include education, influence, lobbying and listening. Policy is communicative work. Via these communications, policymakers can have three aims: to manage stakeholders, to seek opportunities for creative problem solving, or to build legitimacy for the process of change (Nagel 2006). These aims are not always compatible, and there is little evidence to support which is more effective or important (Nagel 2006). Sometimes the very substance of the policy is devised by communicative work with stakeholders – the deliberative democracy perspective (see Mooney, Chapter 13). Such an approach allows for flux and transformation and accepts that organisation (here content and agreement) may emerge from chaos (Morgan 1997). However, if the substance of policy is determined by the process, the definition of success and measurement or evaluation of success factors becomes difficult.

Box 12.2

A detailed documentation of the stakeholder process now forms a regular part of policy development. A good example is the recently released national Australian Palliative Care Needs Assessment Guidelines (Girgis et al 2006), which have as appendices a list of the 58 organisations and groups involved in the review, and details of the individuals that represented these groups at a national consensus meeting. However the investment of time and resources required can be substantial, and may not always seem appropriate for the issue. For instance, one recent improvement initiative in a single London sexual health clinic had representatives of approximately 65 stakeholder groups involved in the oversight group (Greenhalgh, 2007 and Greenhalgh, 2007). This caused process and practical difficulties including obtaining sufficiently large venues. The Australian Commission’s review of national safety and quality accreditation had involved 125 meetings (from one-on-one to focus group), reviewed over 140 written submissions, published four discussion papers and presented at multiple conferences to develop an alternative accreditation model. However, this is a potential policy reform that will affect the whole healthcare system and this investment in stakeholder consultation is critical to its success.

Enhanced stakeholder engagement remains problematic. Harvey (1991:14) goes on to naively say that ‘if the agreed objective is to achieve the greatest health benefit to the community, an equitable distribution of health services and programs will be possible’. Rather, stakeholders will campaign for their own definitions of an equitable distribution. A Victorian study suggests that the major influence on health policy comes from a relatively small network of powerful individuals (Lewis 2006). Public interest groups and social movements have limited bargaining power: ‘People join such groups as part of active citizenship. Their commitment to these social movements – for example to the environment … or disability rights is usually additional to their … work in paid employment’ (Willis 2002:182). If stakeholder tools are protests and lobbying, they can only bargain with government when they have an organisation able to represent their interests.

Stakeholders also include private interest groups such as the Australian Medical Association (AMA) and the medical colleges who ‘act as conservative self-serving lobby groups and as forces for reform’ (Willis 2002:183). ‘Private groups have expertise that the government must take into account for political reasons. They are able to make informed critical comment on government policy’ (Willis 2002:184–185). As Dzur (2002:178) notes, the professions are ‘crucial dimensions of the intermediary realm between individual and state. They are political entities, not just when they form interest groups, but because in the intermediary realm of civil society, professions possess the power to distract, encourage, limit and inform public recognition of and deliberation over social problems’. Attempts to engage clinical stakeholders may appear adequate on paper, but often fail in practice if only those with the time and interest to attend meetings are consulted. There is a need to ensure stakeholders are representative members of a community (Bound 2006) and this is especially so where policy is co-created.

Improved accessibility of information

The modern versions of the one-page 1990 policy directives would now take longer to develop due to the need to incorporate evidence and stakeholder input. However they would be immediately available, once ‘signed off’, to anybody in the health system with access to the intranet, including frontline staff (see Box 12.3). Accessibility also brings implicit accountability for actions contained in the policy and the potential for ad hoc implementation, although this may not be an issue if an implementation plan accompanies a policy directive.

Box 12.3

The internet is not as profound a means of communication as might appear. Alert systems for what is new and important are not well developed. Departmental websites are complex and information rich, but require a high level of skill to navigate. Sophisticated search engines are rarely available. Few staff have the knowledge of structures that would determine the potential location. As an example, a search on the NSW Health internet site for a guideline that was said to accompany a circular entitled ‘Management of fresh blood components’ was made using the terms ‘transfusion guidelines’, ‘blood guidelines’ and ‘management of fresh blood components’ and produced no items. A search simply using the term ‘blood’ produced 365 documents.

For some staff the content of policy directives may become like the ‘small print’ on a banking document – what could be described as ‘white policy noise’, something not for one to read or act on, yet whose existence provides a veiled threat. The potential is for a culture to develop defined by loss of control – ‘they keep making rules’. Clinicians may feel unable to influence, or even read or find the volume of policy material that is relevant to their work. Clinicians receive around one policy circular per week in NSW (personal communication). Further, the complexity of more highly developed policies may limit implementation, as the message is no longer simple, and a large volume of material will dissuade people from reading it in detail unless they ‘have to’. Those who ‘have to’ read such policies are managers, and some organisational power undoubtedly comes from managers understanding the rules and regulations which ‘they’ apply variably. Yet there are those who don’t ‘have to’ read them for whom the policy may have direct impact, or should inform their work. Policy is not well able to penetrate beyond the professional bureaucracy to practitioners; doctors in particular often don’t see themselves as accountable for implementation of policy, including safety and quality strategies (Shekelle 2002).

The term ‘system’ is often used to describe health services organisation, and doctors objectify, reify and distance themselves from ‘the system’ (Jorm et al 2006). Vilification of management is the norm. The problems of a teaching hospital in Sydney were recently attributed by doctors to the (local) management’s ‘obsession with filling out useless forms and mindless application of protocol’ (Benson & Wallace 2007:10). The call was to ‘(f)ire all the middle management in hospitals who have created this environment and contribute nothing and you will have plenty of hospital funding’ (Benson & Wallace 2007:10).

According to Lipsky (1980) public policy is not best understood as made by government or by high-level bureaucrats but created by the daily actions of ‘street-level’ workers. These street-level workers are the professionals actually involved in service delivery and they make policy in three ways: by possession of information (e.g. indicators), by policymaking by discretion (the choices professionals have about the extent to which they follow policy) and by cumulative action (e.g. mass refusal). This means that messages, information and influence pass from top to bottom and bottom to top.

Policy directives in 2007

Policy directives in 2007 are quite different from those in 1990 (see Box 12.4). Those relating to blood and payment of ambulance transport are freely available on health department intranet sites and the internet. Each circular still contains a distribution list, which is still the subset of staff who ‘have to’ receive, read and take responsibility for others acting on the directive. However, the mechanism for reaching managers and clinicians is still inconsistent and relies on people at multiple decision points within the health department and corporate structures of private services being aware of the policy and recognising its applicability to their service. Further, many medical staff don’t functionally report to a manager as many are part-time contractors.

Box 12.4

The ambulance transport charges document has been regularly updated, most recently in 2004 and still deals exclusively with transport charges. The charges are now detailed; the document is three pages long, and the costs for a transfer capped at just under $4000, but there is still no reference to the broader context of the clinical and social aspects of patient transfers.

The blood directive has also been updated multiple (10) times and 2002/92 is now a circular entitled ‘Management of Fresh Blood Components’. It has increased in size to two pages with a cover sheet detailing status. It was published on 27 January 2005 and is due for review in 2010. It has four major headings. The first is the ‘Purpose of this circular’. This is stated to be: ‘… For use by clinicians, hospital transfusions staff and health service managers … involved in the collection, storage and transfusion of fresh blood and blood components. It sets out the mandatory requirements for … transfusion therapy’. The circular references an accompanying guideline that includes the mandatory requirements and additional information on better practice. Justification is also given for both the circular and the guidelines; these are: avoiding transfusion reactions and appropriate use of a ‘precious resource’. After ‘Purpose’, the subsequent headings are ‘Obligations of a clinician’, ‘Obligations of the hospital transfusion service’ and ‘Obligations under clinical governance’.

The complex committee structure (that includes many stakeholders) for the governance of blood and blood products in NSW is also available on the NSW Health internet site (see www.health.nsw.gov.au/public-health/clinical_policy/blood/nswarrangements/index.html), but is not included or referenced in either the circular or the guidelines. The ‘Guidelines’ are a 21-page document referenced with both legislative requirements and evidence. The guidelines do include mention of the subjects of the 1990 memo: information on directed blood donation and a mention of a reporting route for graft versus host disease. However while the need to obtain patient consent and explain the risks and benefits of transfusion forms part of the guideline (Appendix on Clinical Care) no details of the risks are provided. There is no tool to discuss risks with patients, yet such a tool is surely necessary for compliance. Internationally the adoption of decision aids to support patient choice has been tardy, despite evidence of the value of such aids (O’Connor et al 2007). The circular specifically details three items that represent only a small part of the total guidelines: transfusion verification procedure, the procedure for collecting and labelling specimens and the statement that small facilities must not store RH negative blood. It is not clear why these three items have been selected to feature in the circular.

The introduction of accountability mechanisms

Here we discuss the introduction of accountability mechanisms, and consider the effect that the safety and quality movement has had on the dynamic development of policy and of practice. We also consider the place of clinical governance as an organisational framework for accountability and improvement, and, last, we discuss the place of regulatory policy.

The effect of the safety and quality movement on the dynamic of policy and practice

Safety and quality introduce special policy issues to health. These are often emotive, used by both politicians and healthcare professionals to achieve their policy aims as stakeholders, and, at times, to resist change. Healthcare is also the subject of intense media coverage, and in the UK the ratio of negative to positive stories in the print media has increased (Alia et al 2001).

It is customary to ascribe the origins of the quality and safety movement to the Harvard Medical Practice study (Brennan et al 1991), the Quality in Australian Healthcare Study (Wilson et al 1995) and the Institute of Medicine report ‘To Err is Human’ (Kohn et al 1999). However, public trust in Australia wavered after a series of high-profile public inquiries into failures in safety and quality of care, namely those concerning:

▪ The King Edward Memorial Hospital, Perth (Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2002)

▪ The Camden and Campbelltown hospitals, Sydney (Pain & Lord 2006)

▪ The Bundaberg Hospital, Queensland (Forster 2005).

The processes, quality and balance of inquiries can vary. Often they take on the characteristics of a witch-hunt (Beckett 2002) as release of information leads to wider, damaging consequences where the innocent can be punished and an atmosphere of hysteria leads to false accusations. But public inquiries can also bring public catharsis (Walshe & Higgins 2002) and substantially alter public opinion (Brunton 2005), especially if they produce appealing and plausible interpretations of events to repair damaged social institutions (Brown 2003), if they become a lever for change (Walshe & Higgins 2002) or through regulatory reform (Quick 2006). Against this backdrop the safety and quality movement uniquely drives policy (Liang 2004) providing reasons to increase regulation (Mello et al 2005) and accountability, the latter often via clinical governance mechanisms.

Clinical governance

The term clinical governance, introduced in 1998 (Donaldson & Gray 1998), describes an organisational accountability framework for improvement, to safeguard high standards and for excellence to flourish in clinical care. Many specific items have subsequently been added to this framework or ‘umbrella’. The NHS clinical governance support team (http://www.cgsupport.nhs.uk/about_cg/) states: ‘Underneath this umbrella are several key components and themes, all of which, when effective, combine to make up good clinical governance … each [element is] of equal value and importance … interdependent and mutually reinforcing.’ While the components in published lists vary, elements can be separated into the disciplinary devices of inspection and moralising devices designed to enhance collaboration (Iedema et al 2005). Inspectorial devices include: data generation and analysis; performance monitoring and management; accreditation; guideline and protocol production and implementation; and the close integration of clinical work data with financial data. Moralising devices include: open disclosure, no blame, a just culture, a safety culture, leadership, teams, collaboratives, consumer involvement and patient centredness.

The current blood circular introduces the notion of ‘obligations under clinical governance’. Clinical governance is a powerful policy framework able to comprehensively envelop all aspects of clinical care and work practices to engage frontline staff to control, direct and theoretically improve care. The multiplicity of devices under the umbrella of clinical governance assists policymakers in developing ‘dispersed and devolved systems of policy implementation, where mechanistic and “top-down” command-and-control processes are ineffectual’ (Flynn 2002:160). Clinical governance in the UK has been described as quite a fundamental shift in the relationship between the state and the healthcare professions (Flynn 2002). Employees are given responsibility for quality and self-surveillance, but performance is also monitored by managers via targets, incentives and sanctions. In Australia different structure and funding arrangements make clinical governance less visible than in the UK.

Regulatory policy

Embedding best practice is difficult (Greenhalgh et al 2005). Medical leaders alone have been unable to improve the quality of care (Dixon et al 2007) and mandating best practice via policy is seen as an alternative. In the 1990s policy directives were not accompanied by tools to implement or monitor uptake, and neither health services nor the health department had mechanisms in place to measure and evaluate policy uptake or effectiveness. Local health service managers were left to determine how policy was implemented, which, not surprisingly, resulted in a variety of processes and procedures across the entire system. Detailing policy specifications to overcome this variation has not been sufficiently successful, giving way to further attempts to enforce healthcare policy by regulation.

A further regulatory strategy commenced in the 1990s when contracts with services began to include performance targets for patient outcomes. These were later associated with sanctions, penalties and incentives. An extension of this strategy is contracting with individuals to achieve key performance indicators (KPIs), that is, requiring managers to meet clinical quality and efficiency targets. Types of accountability include financial accountability introduced in the 1970s (The ‘Cogwheel’ Reports 1967/1972/1974), and the introduction of pay-for-performance (P4P) schemes that link clinical and financial accountabilities. Nagel (2006:4) suggests that ‘the trend in public management is focused on outcome-based policy where public sector managers are held accountable for results and afforded more discretion as to the means of their achievement’. This approach, implemented widely in the US (see for instance the AHRQ resources at www.ahrq.gov/qual/pay4per.htm), is seen by McLoughlin & Leatherman (2003) as imperative to achieve improvements in care in the UK. Paying general practitioners in the UK to ensure basic management of chronic disease, for instance, has proven effective (Dixon et al 2007), albeit unexpectedly expensive. Queensland is trying a more limited approach via the development of clinical networks based on the Queensland Health Clinical Practice Improvement Centre (CPIC) (Ward 2006) that use clinical practice improvement payments to provide a financial incentive for good-quality care linked to performance against defined targets that requires networks to collect and report data.

Further, patient safety has been used to justify a push for so called ‘responsive regulation’ to replace self-regulation (Healey & Braithwaite 2006). Mello et al (2005:375) in turn call for ‘rational regulation’ arguing that ‘(p)atient safety today exemplifies that eclectic mix of regulation that can occur when a new problem is exposed to the general public’. Australian regulation is undoubtedly eclectic. The mix of accreditation, licensing and the requirements of private insurers and government departments is a duplicative, expensive and unreliable way of ensuring the safety and quality of healthcare. Other regulatory experiments in Australia include the Quality Systems Assessment (QSA) program that aims to provide evidence of assurance of compliance with policies, standards and guidelines and assessment of the level of development of a patient safety system, clinical quality improvement, improvement at a local, facility and systems level and the identification of future risks to patient safety (see www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/moreinfo/more_QSA.html).

Individual inquiries into health services also bring increased regulation. The Health and Quality Complaints Commission (HQCC) was established in Queensland following the Forster Report (2005) into Bundaberg Hospital. This oversight body aims to guide health service providers about what is expected in the areas of monitoring and improving the quality of health services. Following its inception, the HQCC has released statutory standards under section 20 of the Act establishing a legal duty that ‘(a) provider must establish, maintain and implement reasonable processes to improve the quality of health services provided by or for the provider, including processes: (a) to monitor the quality of health services and (b) to protect the health and well being of users of health services’.

Conclusion

A view often expressed in health circles is that despite the rhetoric of reform little has changed. We do not share this view and our examination of policy instruments over the past 17 years indicates just how far the system has come. Policy developed now reflects myriad developments in healthcare improvement that are in turn reflected in the dynamics of policy development and implementation. Policy directives in healthcare in 2007 are very different in format and in the nature of their development from those of 1990.

Modernising policymaking has been irregular across Australia and across the health sector, but it has occurred. Stakeholders are more visible, are consulted in greater numbers and more often. Engaging stakeholders early in the policy process is now commonplace. Distributing policy is electronic and immediate. This alone does not necessarily translate into greater penetration of policy, but the increasing accompaniment of policy initiatives by guidelines, tools and extensive education and training suggest that implementation is being taken seriously and is being more effective. Evidence may never quite have the place in policymaking that some desire; there are good reasons why it sits apart, but efforts are under way to maximise its use in policymaking.

Accountability mechanisms have taken on a broader framing in health policy in response to quality and safety concerns. Clinical governance is a somewhat vague umbrella of elements that constrain and direct practice, reinforced by an increasing tendency to regulation. The hybrid of clinical governance aims to codify clinical standards and to evaluate performance while giving the semblance of delegated autonomy, but in reality professional expertise becomes subject to increased managerial control (Flynn 2002). There is nothing protective about the umbrella of clinical governance. It will not protect the status quo but it will have a profound effect on practice. Indeed, the proliferation of accountability mechanisms may mean that there is a risk that monitoring can become an end in itself (Michael 2005).

Clearly, in this context the key questions for modern health policy are: What is the best mix of policy levers to improve health system performance? (Dixon et al 2007); and What will health policy look like in the future? Hopefully there will be less ambiguity. While ambiguity serves to protect the writers and implementers of policy against failure, it must be reduced. The best way to reduce it is by using policy pilots. ‘Although pilots or policy trials may be costly in time and resources and may carry political risks, they should be balanced against greater risk of embedding preventable flaws into a new policy’ (Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office 2003:2). Policy pilots give more prominence to the whole process of evaluation that can then continue into long-term outcomes evaluation. Policy pilots do have significant resource implications, but ‘getting it wrong’ also has costs, and those that pay in healthcare are the patients who ultimately suffer from unsafe and poor-quality care. Policy developers must build motivation to participate via communicative work at all levels during development and add to it via training. Health policy must be allowed to do its job – to better manage clinical work.

References

Alia, N.; Lo, T.; et al., Bad press for doctors: 21 year survey of three national newspapers, BMJ 323 (7316) (2001) 782–783.

Almeida, C.; Bascolo, E., Use of research results in policy decision-making, formulation, and implementation: a review of the literature. (2006) Ca Saude Publica, Rio de Janeiro 22; sup:S7–S33.

Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare, Lessons from the Inquiry into Obstetrics and Gynaecological Services at King Edward Memorial Hospital 1990–2000. (2002) Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare, Canberra.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Health and Community Services Labourforce 1991(AIHW cat no HWL 19). (2001) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra.

Beckett, C., The Witch-Hunt Metaphor (And Accusations against Residential Care Workers), British Journal of Social Work 32 (2002) 621–628.

Benson, K.; Wallace, N., No commitment to care: staff bemoan lack of care. (2007) The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney.

Booth, T., Developing Policy Research. (1988) England; Brookfield, VT, Avebury Aldershot, Hants.

Bound, H., Assumptions within Policy: A Case Study of Information Communications and Technology Policy, Australian Journal of Public Administration 65 (4) (2006) 107–118.

Bowen, S.; Zwi, A.; et al., What evidence informs governmental population health policy? Lessons from early childhood intervention policy in Australia, NSW Public Health Bulletin 16 (2005) 11–12.

Brennan, T.A.; Leape, L.L.; et al., Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients, Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. New England Journal of Medicine 324 (6) (1991) 370–376.

Brown, A., Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Enquiry Report, Organization Studies 25 (1) (2003) 95–112.

Brunton, W., The place of public inquiries in shaping New Zealand’s national mental health policy 1858–1996, Australia and New Zealand Health Policy 2 (24) (2005); doi10.1186/1743-8462-2-24.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Received Wisdoms: How health systems are using evidence to inform decision-making. (2007) Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Vancouver.

Culyer, A.; Lomas, J., Deliberative processes and evidence informed decision making in healthcare: do they work and how might we know?Evidence and Policy 2 (3) (2006) 357–371.

Dixon, J.; Chantler, C.; et al., Competition on Outcomes and Physician Leadership Are Not Enough to Reform Health Care, JAMA 298 (12) (2007) 1445–1447.

Dobrow, M.; Goel, V.; et al., The impact of context on evidence utilisation: A framework for expert groups developing health policy recommendations, Social Science and Medicine 63 (2006) 1811–1824.

Donaldson, L.; Gray, J., Clinical Governance: a quality duty for health organisations, Quality in Health Care 7 (suppl) (1998) S37–S44.

Dzur, A., Democratizing the Hospital: Deliberative-Democratic Bioethics. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 27 (2) (2002) 177–211.

Flynn, R., Clinical governance and governmentality, Health, Risk and Society 4 (2) (2002) 155–173.

Forster, P., Queensland Health Systems Review – Final Report. (2005) Qld Government, Brisbane.

Girgis, A.; Johnson, C.; et al., Palliative Care Needs Assessment Guidelines. (2006) Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra.

Government Chief Researcher’s Office, Trying it out: the role of ‘pilots’ in policy-making. (2003) Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, London.

Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; et al., Diffusion of Innovations in Health Service Organisations. A systematic literature review. (2005) Blackwell, Oxford.

Harvey, R., Making it Better. Strategies for improving the effectiveness and quality of health services in Australia. (1991) Australian Government, Canberra; Background Paper No 8.

Healey, J.; Braithwaite, J., Designing safer health care through responsive regulation, Medical Journal of Australia 184 (10) (2006) S56–S59.

Hoff, T.; Jameson, L.; et al., A review of the literature examining linkages between organizational factors, medical errors, and patient safety, Medical Care Research & Review 61 (1) (2004) 3–37.

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, House of Commons Science and Technology Committee: Scientific Advice, Risk and Evidence Based Policy Making. (2006) The Stationery Office, London.

Iedema, R.; Braithwaite, J.; et al., Clinical governance: complexities and promises, In: (Editors: Stanton, P.; Willis, E.; Young, S.) Health Care Reform and Industrial Change in Australia: Lessons, Challenges and Implications (2005) Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke, pp. 253–278.

Innvaer, S.; Vist, G.; et al., Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review, Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 7 (4) (2002) 239–244.

Jorm, C.; Travaglia, J.; et al., Why don’t doctors engage with the system? In: (Editor: Iedema, R.) Hospital Communication: Tracing complexities in contemporary healthcare organisations (2006) Palgrave, Basingstoke, pp. 222–243.

Kohn, L.; Corrigan, J.; et al., To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. (1999) National Academy Press, Washington DC.

Laupacis, A.; Straus, S., Relevance and Rigor of Systematic Reviews, Annals of Internal Medicine 147 (2007) 273–274.

Lewis, J., Being around and knowing the players: Networks of influence in health policy, Social Science & Medicine 62 (2006) 2125–2136.

Liang, B., A Policy of System Safety, Harvard Health Policy Review 5 (1) (2004) 6–20.

Lipsky, M., Street-Level Bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public services. (1980) Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

McLoughlin, V.; Leatherman, S., Quality or financing: what drives design of the health care system?Quality & Safety in Health Care 12 (2) (2003) 136–142.

Medical Professionalism Project, Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter, Ann Intern Med 136 (3) (2003) 243–246.

Mello, M.; Kelly, C.; et al., Fostering Rational Regulation of Patient Safety. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 30 (3) (2005) 375–426.

Meyer, J.; Alteras, T.; et al., Toward more effective use of research in state policymaking, The Commonwealth Fund (2006) 1–26.

Michael, B., Questioning Public Sector Accountability, Public Integrity 7 (2) (2005) 95–109.

Milewa, T., Health technology adoption and the politics of governance in the UK, Social Science and Medicine 63 (2006) 3102–3112.

Morgan, G., Images of Organization. (1997) Sage, London.

Nagel, P., Policy Games and Venue-Shopping: Working the Stakeholder Interface to Broker Policy Change in Rehabilitation Services, Australian Journal of Public Administration 65 (4) (2006) 3–16.

National Health Strategy Working Group, Hospital services in Australia: access and financing. National Health Strategy Issues Paper No. 2. (1991) Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

O’Connor, A.; Wennberg, J.; et al., Toward The ‘Tipping Point’: Decision Aids And Informed Patient Choice, Health Affairs 26 (3) (2007) 716–725.

Oxman, A.; Lavis, J.; et al., The use of evidence in WHO recommendations, The Lancet 369 (9576) (2007) 1883–1889.

Pain, C.; Lord, R., Lessons from Campbelltown and Camden Hospitals, ANZ J Surg 76 (Suppl 1) (2006) A42–A44.

Palmer, G.; Short, S., Health Care and Public Policy 3rd Edition. (2000) Macmillan Press, Australia.

Quick, O., Outing Medical Errors: Questions of Trust and Responsibility, Medical Law Review 14 (2006) 22–43.

Shekelle, P.G., Why don’t physicians enthusiastically support quality improvement programmes?Quality & Safety in Health Care 11 (1) (2002) 6.

Sheldon, T., Making evidence synthesis more useful for management and policy-making, Journal of Health Services & Research Policy 10 (Suppl) (2005) 1–5.

Shojania, K.G.; Grimshaw, J.M., Evidence-Based Quality Improvement: The State of The Science, Health Affairs 24 (2005) 138–151.

Shortell, S.; Rundall, T.; et al., Improving Patient Care by Linking Evidence-Based Medicine and Evidence-Based Management, Journal of the American Medical Association 298 (2007) 673–676.

Spitz, B.; Abramson, J., When Health Policy Is the Problem: A Report from the Field. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and the Law 30 (3) (2005) 327–365.

Swerissen, H.; Duckett, S., Health Policy and Financing, In: (Editors: Gardner, H.; Barraclough, S.) Health Policy in Australia (2002) Oxford University Press, Victoria, pp. 13–48.

Tunis, S.; Stryer, D.; et al., Practical Clinical Trials Increasing the Value of Clinical Research for Decision Making in Clinical and Health Policy, JAMA 290 (12) (2007) 1624–1632.

Walshe, K.; Higgins, J., The use and impact of inquiries in the NHS, BMJ 325 (2002) 895–900.

Willis, E., Interest Groups and the Market Model, In: (Editors: Gardner, H.; Barraclough, S.) Health Policy in Australia (2002) Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp. 179–200.

Willis, E.; Stanton, P.; et al., Health Sector and Industrial Reform in Australia, In: (Editors: Stanton, P.; Willis, E.; Young, S.) Workplace Reform in the Healthcare Industry: The Australian Experience (2005) Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, pp. 13–19.

Wilson, R.M.; Runciman, W.; et al., The Quality in Australian Health Care Study, MJA 163 (1995) 458–471.

Appendix 2. NSW Health circular 90/122 (issued December 1990)

|