Chapter 4 The Cervicobrachial Region

Affections of the brachial plexus are usually the result of either compression or injury. The resultant symptoms and signs are often confusing, but these disorders should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of neuropathies of the upper extremity.

Anatomy

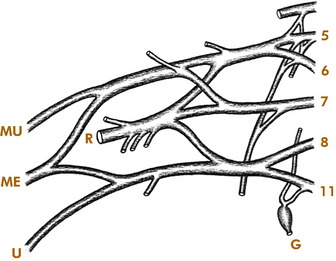

The brachial plexus is formed by the anterior rami of the last four cervical and first thoracic nerves (Fig. 4-1). In general, the upper portion of the plexus innervates the shoulder abductors, external rotators, and the elbow flexors. It also provides sensation to the shoulder and radial side of the arm. The lower portion of the plexus primarily innervates the forearm and hand muscles and provides sensation to the ulnar side of the arm, forearm, and hand. The first thoracic ramus also communicates with the first thoracic ganglion, through which sympathetic fibers are carried to the face from the spinal cord. Thus, involvement of the lower portion of the plexus by disease or injury may produce Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, miosis, enophthalmos, and anhidrosis).

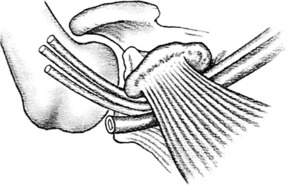

The plexus passes distally between the middle and anterior scalene muscles, which attach to the first rib (Fig. 4-2). Beneath the clavicle, it is joined by the subclavian artery. The subclavian vein passes anterior to the scalenus anticus muscle. Artery, vein, and plexus then enter the axilla beneath the pectoralis minor muscle, with the lower trunk of the plexus (C8, T1) lying on the first rib.

Thoracic Outlet Syndromes

CERVICAL RIB SYNDROME

The cervical rib usually arises from the seventh cervical vertebra and is the most common cause of neurovascular compression at the base of the neck (Fig. 4-3). The condition may be bilateral. The rib or its fibrous extension narrows the interval between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and produces a higher barrier over which the neurovascular structures must arch on their way into the arm. In older patients or those with muscular weakness, the shoulder may also sag more than normal, which further increases the tension on the neurovascular structures. The compression may also be increased by carrying a heavy object.

In the absence of a cervical rib, compression can occur between the middle and anterior scalene muscles because of abnormal insertions or the presence of additional muscle slips in the interscalene interval (scalenus anticus syndrome).

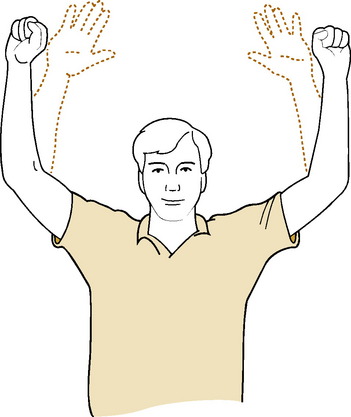

Provocative positioning tests are often described in the assessment of thoracic outlet syndromes. Adson’s test may be positive in cervical rib and scalenus anticus syndromes (Fig. 4-4). This test takes advantage of the fact that by tensing the scalene muscles the interval between them is decreased, and any existing compression of the subclavian artery is increased. The test is performed by having the patient breathe deeply, extend the neck, and turn the chin toward the affected side. When the test is positive, a decrease in the radial pulse is noted, and pain is reproduced. If the test is negative, it is repeated with the chin turned to the opposite side. Although a positive test result is suggestive of compression in the interscalene region, it is often positive in the normal population and is not necessarily diagnostic of cervical rib or scalenus anticus syndrome. Symptoms can also be reproduced occasionally by exercising the fingers with the arms elevated (Fig 4-5).

Roentgenographic examination may reveal an extra rib extending from the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra (Fig. 4-6). The rib may be fully developed or rudimentary, and it is often bilateral. Its presence does not necessarily imply that it is symptomatic, however, because cervical ribs are often present in asymptomatic individuals.

COSTOCLAVICULAR SYNDROME

The syndrome is occasionally seen in individuals who are required to carry heavy packs on their shoulders. Intermittent numbness and pain in the hand and arm are the most common symptoms. These symptoms may be reproduced by the costoclavicular maneuver (Fig. 4-7). In this test, the shoulders are drawn downward and backward, and any change in the radial pulse or reproduction of symptoms is noted.

HYPERABDUCTION SYNDROME

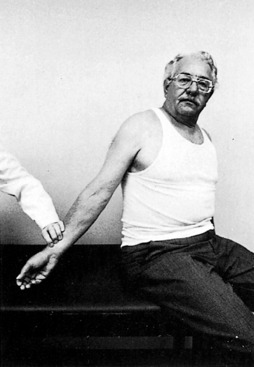

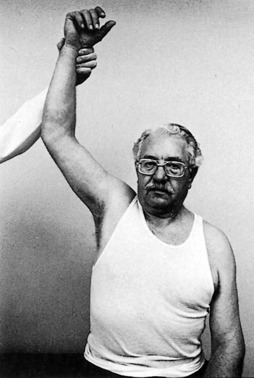

Neurovascular symptoms may also follow prolonged assumption of the position of shoulder hyperabduction. This position is often assumed during sleep and in certain occupations such as overhead painting. The neurovascular structures are compressed as they pass under the coracoid process and pectoralis minor muscle with the arm in hyperabduction (Fig. 4-8). Numbness and paresthesias are common, but the pain tends to be less severe than that seen in the other compression syndromes. Wright’s test (diminution of pulse or reproduction of symptoms on hyperabduction of the arm) may be positive (Fig. 4-9).

TREATMENT

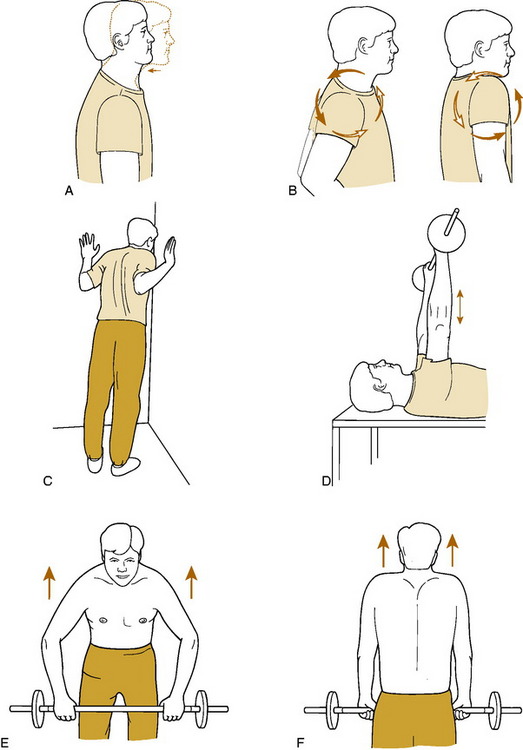

Patients with vascular complications should be promptly referred. Otherwise, the initial treatment is conservative. Symptomatic relief may be obtained by resting the elbow of the affected side on the arm of the chair, thereby elevating the shoulder. A sling may serve the same purpose. Specific strengthening and stretching exercises for the shoulder girdle muscles taught by a knowledgeable physical therapist can help (Fig. 4-10). Faulty posture and poor body mechanics should be corrected, and positions that aggravate the condition should be avoided. General health factors should be addressed as well, especially deconditioning and obesity. If symptoms are worsened by certain work activities, a minor alteration in the position of the arms while working could help.

Fig. 4-10 Shoulder exercises for thoracic outlet syndrome. A, Neck retraction. The head is pulled straight back, keeping the jaw level. The position is held for 5 to 10 seconds. B, Shoulder rolls are performed by shrugging up, back, and down in a circular motion. C, Corner stretch. With the hands at shoulder height, the patient stands and leans into a corner until a gentle stretch is felt. This is held for 5 to 10 seconds. D, To strengthen the serrati, the weight is pushed upward so that the shoulders are lifted off the table. E and F, The trapezius is strengthened by raising and drawing the shoulders backward to bring the scapulae upward and together.

Birth Palsy

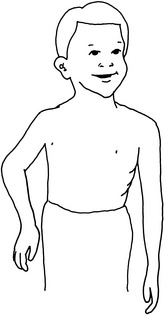

ERB–DUCHENNE PARALYSIS

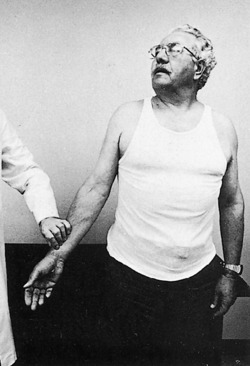

This is the most common type of obstetric paralysis. Damage to the upper roots (C5 and C6) leads to paralysis of the deltoid muscle, the external rotators of the shoulder, the elbow flexors, and the supinators of the forearm. Residual weakness of these muscles leads to the characteristic “waiter’s-tip” position in which the arm is held adducted and internally rotated and the forearm is pronated (Fig. 4-11). Wrist and finger function are usually normal.

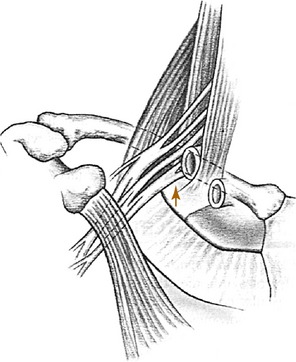

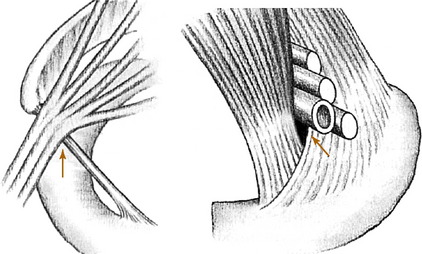

Brachial Plexus Injuries

The initial treatment is always conservative for the first several weeks. Range-of-motion exercises are begun to prevent joint stiffness. During this time the patient is observed for spontaneous recovery. If this occurs, the prognosis is often favorable. If it does not occur, the patient should be evaluated to determine whether a reparable lesion is present. Magnetic resonance imaging, myelography, and electromyography can be helpful in this regard. If the myelogram shows the presence of several traction meningoceles or dye pockets, this indicates that the nerve roots have been avulsed from the cord. This suggests that the injury is probably complete and not reparable and that the prognosis is poor. This status is also suggested by the absence of any appropriate electromyographic activity.

Aston JW:. Brachial plexus palsy. Orthopedics. 1979;2:594.

Britt LP. Nonoperative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms. Clin Orthop. 1967;51:45-48.

Eng GD. Brachial plexus palsy in newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1971;48:18-28.

Fechter JD, Kuschner SH. The thoracic outlet syndrome. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1243-1251.

Grant JCB. A method of anatomy, ed 6. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1958.

Leffert RD. Thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2:317-325.

Nichols HM. Anatomic structures of the thoracic outlet. Clin Orthop. 1967;51:17-25.

Oates SD, Daley RA. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12:705-718.

Omer GEJr, Spinner M. Management of peripheral nerve problems. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1980.

Roos DB. The thoracic outlet syndrome is underrated. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:327-328.

Roos DB. Thoracic outlet syndromes: update 1987. Am J Surg. 1987;154:568-573.

Tachdjian MO. Pediatric orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1972.

Wilburn AJ. The thoracic outlet syndrome is overdiagnosed. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:328-330.