Chapter 3 The Cervical Spine

The cervical spine is exceeded only by the lumbar spine in the number of patients affected by conditions causing pain or dysfunction to it. These disorders vary from those that are annoying to those that may be functionally disabling. The diagnosis and treatment of these disorders are a major part of orthopedics.

Anatomy

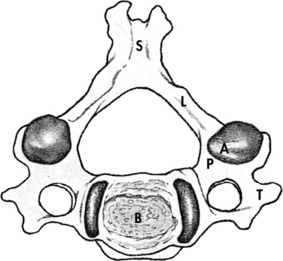

Seven cervical vertebrae make up the bony elements of the cervical spine. A typical cervical vertebra is similar to other vertebrae in that it is composed of a body and a neural arch (Fig. 3-1). The neural arch is composed of two pedicles that form the sides and two laminae that meet in the midline to form the roof. Projecting dorsally where the laminae meet is the spinous process, and projecting laterally from the junction of the pedicle and lamina is a transverse process on each side. Two articular processes, the superior and inferior, project upward and downward, respectively, from the junction of the pedicle and laminae on each side and articulate with similar processes on adjacent vertebrae to form the zygapophyseal or facet joints.

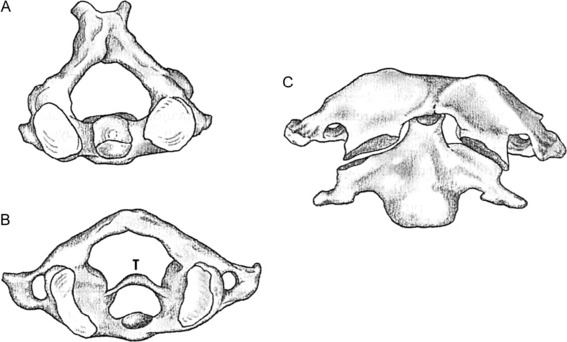

The first two cervical vertebrae are atypical in that C1, the atlas, has no body (Fig. 3-2). Its body is attached to C2, the axis, and forms the dens, or odontoid process. This arrangement allows for most of the rotation in the cervical spine. Strong ligaments bind C1 to C2, the most important of which is the transverse ligament. The seventh cervical vertebra, vertebra prominens, is also somewhat atypical in that it has a long spinous process that is easily palpable beneath the skin. (Patients sometimes misinterpret this bony prominence and its overlying soft tissue as a “mass.”)

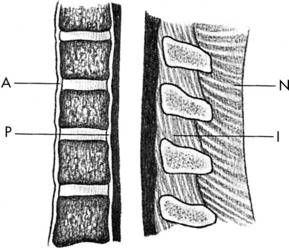

Several major ligaments stabilize the cervical spine (Fig. 3-3). The anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are applied to the respective surfaces of the vertebral bodies. The posterior longitudinal ligament tends to be somewhat weak laterally where it crosses the disc, thus forming a point where disc herniation may occur. Some gliding motion is allowed to occur between vertebrae by relatively weak capsular ligaments that bind together each articular joint. The ligamentum flavum, or yellow ligament, is situated between adjacent laminae, and in the cervical spine, extremely strong ligaments—the nuchal ligament and interspinous ligaments—provide posterior support.

The vertebrae are separated from each other by the intervertebral discs, which constitute approximately one fourth of the length of the vertebral column. Each disc is composed of an inner nucleus pulposus, which is mainly gelatinous, and an outer layer, the anulus fibrosus, which is mainly fibrous. The discs distribute stress over a wide area of the vertebrae, absorb shock, and allow mobility. The nucleus pulposus has a very high water content in early life, but with age this tends to diminish. With this loss of water, abnormal pressures begin to be exerted on the anulus, which may lead to herniation and/or disc degeneration. Pathologic changes in adjacent structures (facet joint arthritis or osteophyte formation) may eventually develop as well.

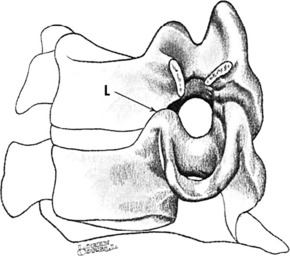

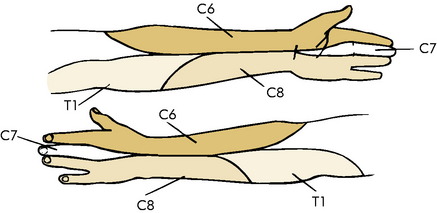

Eight pairs of nerve roots arise from the cervical spinal cord. Each nerve exits above the vertebra of the same number. Thus, the sixth nerve root exits at the C5–C6 disc space. Each nerve, except the first two pairs, leaves the spinal column by passing through an intervertebral foramen (Fig. 3-4). Each foramen has as its superior and inferior boundaries the pedicles of the adjacent vertebrae. Posterolaterally, it is bounded by the apophyseal joint and, anteromedially, by the so-called joint of Luschka. In the cervical spine, this foramen is quite small and is almost entirely occupied by the nerve root. Thus, anything that compromises this space, such as disc degeneration with spur formation, could cause pressure on the nerve root.

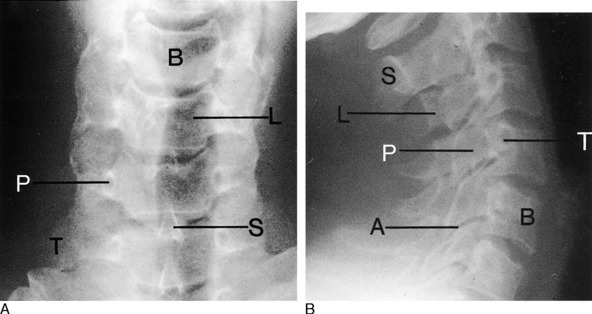

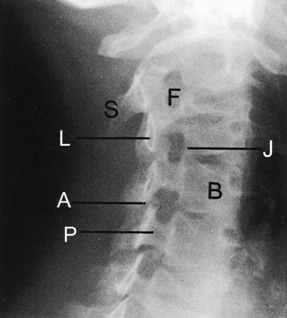

Roentgenographic Anatomy

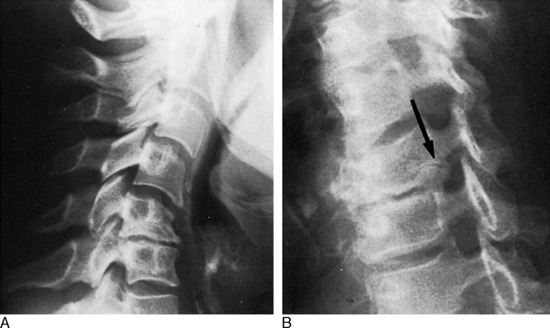

The examination of all neck disorders should include a standard roentgenographic evaluation. The roentgenographic features of the cervical spine are well visualized by the following: (1) anteroposterior view (Fig. 3-5); (2) lateral views in flexion and extension; (3) oblique views in both directions to visualize the intervertebral foramen (Fig. 3-6); and (4) an open-mouth odontoid view to visualize the odontoid process and the relationship between C1 and C2.

Cervical Disc Syndromes

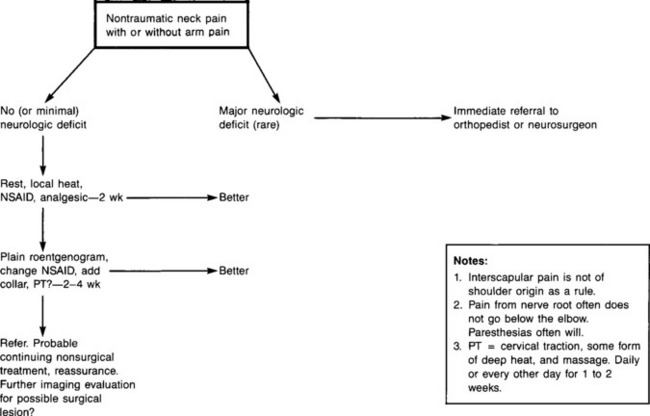

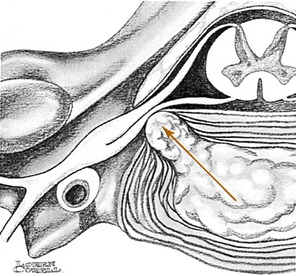

Disease of the cervical spine as a result of disorders of the disc will affect 50% of the population at some time, usually patients between the ages of 30 and 60. More than 90% of disc lesions in the cervical spine occur at the C5 and C6 levels, those being the most mobile segments. As disc degeneration occurs, two types of lesions result that produce very similar symptoms. The first of these is the soft disc protrusion or nuclear herniation. With this lesion, most common in the younger patient, a mass of nucleus pulposus begins to bulge outward, usually posterolaterally, at the area of the greatest weakness in the anulus fibrosus (Fig. 3-7). With severe disc protrusion, compression of the nerve root may occur, resulting in arm symptoms and radicular pain. Less severe herniation may produce only referred or axial spine pain, usually one-sided.

FIG. 3-7 Disc herniation (arrow) causing nerve root compression. Spur formation may occur in the same area.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Pain associated with disc disease usually develops gradually. Degeneration or slow herniation may initially cause only neck and referred pain, which often begins in the interscapular area and may be mistaken for a shoulder disorder. It is almost always unilateral. Patients may complain of a tightness or stiffness in the neck that worsens with activity. Morning stiffness is common, and certain movements, especially extension, exacerbate the pain. Looking backward over the shoulder of the affected side may also intensify the pain. In rare cases, pain in the anterior aspect of the chest (“cervical angina”) or breast may be the presenting complaint. Coughing, sneezing, and straining can accentuate the pain. If nerve root irritation or compression develops, pain may radiate into the shoulder and arm and along the radial aspect of the forearm (Fig. 3-8). Numbness and tingling are often noted in these same areas, and referred pain, which does not follow a dermatome pattern, is common along the upper medial border of the scapula. Headaches are not uncommon, and dysphagia has even been reported secondary to large anterior osteophytes. Headache or jaw pain may be present with high disc lesions. Patients with radicular pain sometimes find relief of the nerve root tension by abducting their arm and resting the forearm on the top of the head.

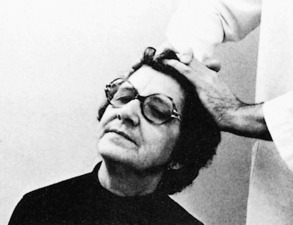

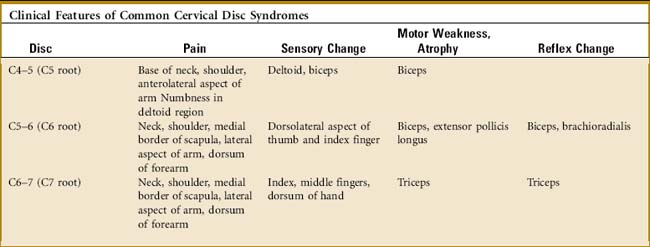

Examination frequently reveals a decreased range of motion. Pain on hyperextension and local tenderness in the cervical spine are often observed. Trigger point tenderness is commonly noted in the area of referred pain in the interscapular region. (This pain is often reproduced by specific neck movements, usually extension with rotation to the involved side.) Pressure against the top of the head also may reproduce the pain in the arm (Fig. 3-9). Some sensory changes are occasionally present along the specific dermatome, but the sensory examination is frequently not very helpful. Motor weakness and reflex changes may be noted (Table 3-1).

SPECIAL STUDIES

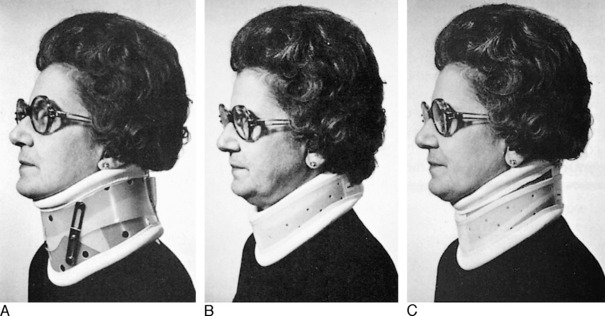

TREATMENT

PROGNOSIS

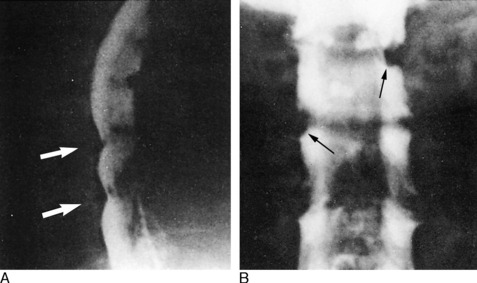

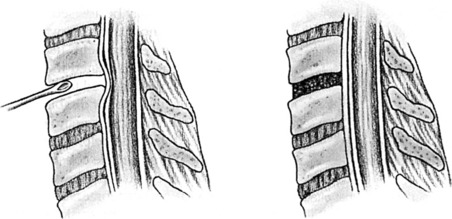

Most patients will improve with time, and fewer than 5% will require surgery. Patience is important. The period required for improvement varies considerably among patients. Several weeks may be needed before full recovery occurs. Patients may be advised, however, that unless a major neurologic deficit is present, there is generally no danger in waiting and continuing conservative treatment. Recurrences occur occasionally and are treated in the same manner. Surgery is reserved for those patients in whom the pain and level of disability become intolerable or in whom a major neurologic deficit has developed. It is indicated for relief of radicular arm pain, but it is not helpful for axial neck pain. The procedure consists of removal of the affected disc, usually followed by arthrodesis of the two adjacent vertebrae with a bone graft (Fig. 3-17). Some soft disc protrusions are occasionally removed without fusion. The arm pain usually subsides immediately after surgery, and osteophytes that have formed in the foramen and adjacent structures are usually absorbed within 9 to 18 months.

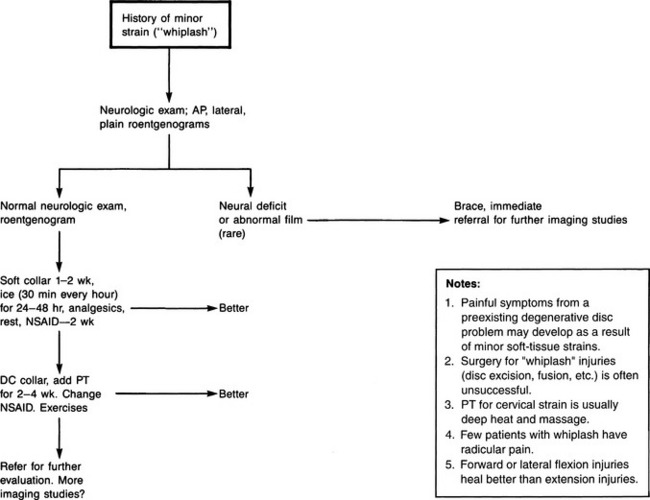

Cervical Sprain

Rarely is there any osseous damage. Most of the force is probably absorbed by ligaments, muscles, and discs, but the specific source of symptoms is often never found. Acute disc protrusion is not common, but disc “injury” may occur on occasion, and serial roentgenograms taken at later dates may show significant progressive degenerative changes. Any soft structures, including muscle, anterior longitudinal ligament, esophagus, and trachea, may be stretched. Dysphagia and hoarseness are sometimes seen shortly after the injury. Hemorrhage and edema may be present in the prevertebral area, and the sympathetic nerve chains, which are located near the vertebral bodies, are occasionally stretched. This may produce somewhat unusual symptoms, such as nausea, tinnitus, blurred vision, and dizziness.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The characteristic clinical features are largely subjective in nature. Frequently, there are very few symptoms immediately after the injury. A few hours later, however, the patient may begin to notice stiffness in the neck followed by pain and an inability to move the neck normally. The pain is generalized to the neck region and may radiate to the occiput along the path of the greater occipital nerve. Shoulder and interscapular discomfort may be noted, and there may even be pain in the anterior chest wall. Radicular pain, suggestive of nerve root compression from disc herniation, is rare. Symptoms such as nausea, tinnitus, blurred vision, and occipital headaches are not uncommon.

SPECIAL STUDIES

After the initial examination, if there is any reason to suspect a significant cervical spine injury, a full lateral roentgenogram of the cervical spine should be taken without moving the patient. This view should always include the body of the seventh cervical vertebra; if it does not, the vertebra is probably being obscured by the shoulder soft tissue shadow. In this case, the shoulders should be pulled down manually and the roentgenogram repeated. If a satisfactory view of C7 still has not been obtained, then a “swimmer’s” view may be performed. If no significant injury is seen on this view, then the remainder of the cervical spine films are obtained. Usually, results of the initial roentgenographic examination are normal, but with the passage of time, reversal of the normal cervical lordosis may rarely be observed (Fig. 3-18). This finding is often seen in patients with prolonged disability. Late degenerative changes may even occur. “Loss of the normal cervical lordosis,” often quoted on early roentgenograms, is probably not significant. Any degenerative changes present in the cervical spine at the time of the initial injury should also be noted for both medical and medicolegal purposes. Further roentgenographic studies are usually not indicated. CT and bone scanning may be helpful to rule out fracture, however. MRI is usually not helpful and is generally not indicated.

TREATMENT

PROGNOSIS

Most patients will improve in 4 to 6 weeks. Less long-term disability and anxiety on the part of the patient will result if aggressive, conservative treatment with good pain management is instituted, especially in the initial stage of the injury.

Disc Calcification

Calcification of the intervertebral disc is not uncommon. It frequently occurs in the dorsal spine of adults in the anulus fibrosus and is probably secondary to a degenerative process. Multiple disc calcifications also occur with ochronosis and other rare metabolic disorders. Disc calcification is usually an incidental roentgenographic finding and generally does not produce symptoms, especially in adults.

Torticollis

CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS

CLINICAL FEATURES

The diagnosis of congenital muscular torticollis generally can be made shortly after birth. The “mass” is usually palpable, and the head is characteristically tilted toward the side of the mass and rotated in the opposite direction (Fig. 3-21). Roentgenograms of the cervical spine are usually performed to rule out injury and congenital osseous disorders of the cervical spine.

TREATMENT

Conservative treatment, if instituted early, usually results in a cure. No improvement can be expected without treatment. In mild deformities, gentle stretching exercises carried out by the mother usually correct the problem. The aim is for full range of motion. The exercises should be repeated several times daily. The crib should be placed so that the child must turn toward the corrected position when someone enters the room. Most cases improve within 6 months. The mass usually resolves by this time as well. Persistent torticollis may result in facial asymmetry and skull deformity (plagiocephaly).

Adson AW, Young HH, Ghormley RK. Spasmodic torticollis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1946;28:299.

Benzel EC. Adjacent-level disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;100(1 Suppl Spine):2.

Bohlman HH. Cervical spondylosis with moderate to severe myelopathy. Spine. 1977;2:151.

DePalma AF, Rothman RH. The intervertebral disc. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1970.

Pennie BH, Agambar LJ. Whiplash injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:277-279.

Robinson RA. The results of anterior interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:1569.

Robinson RA, Smith GW. Anterolateral cervical disc syndrome. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1955;96:223.

Ruge D, Wiltse LL. Spinal disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1977.

Scoville WB. Types of cervical disk lesions and their surgical approaches. JAMA. 1966;196:479-481.

Sherman WD, et al. Calcified cervical intervertebral discs in children. Spine. 1976;1:55.

Tachdjian MO. Pediatric orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1972.