19 The breast

Anatomy and physiology

Anatomy

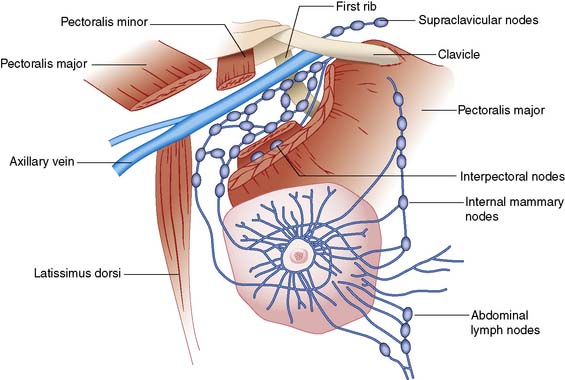

The main route of lymphatic spread of breast cancer is to the axillary nodes, which are situated below the axillary vein. On average, there are 20 nodes in the axilla below the axillary vein (Fig. 19.1). These are separated into three levels by their relation to the pectoralis minor muscle. Nodes lateral to the pectoralis minor are considered level I, those beneath are classified as level II, and the nodes medial to pectoralis minor are level III. Level I nodes, which are nearest the breast, are usually affected first by breast cancer. In less than 5% of patients, levels II or III nodes are involved without level I nodes being affected. Lymph also drains to the internal mammary nodes. Occasionally, the main route of lymph drainage of a cancer is to the interpectoral nodes situated between the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

Evaluation of the patient with breast disease

Clinical examination

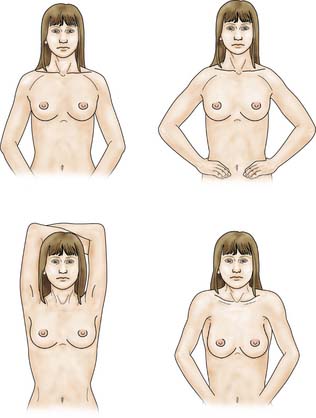

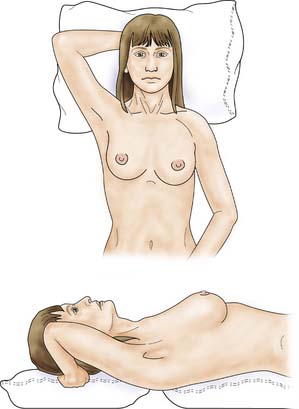

The patient is asked to undress to the waist and sit facing the examiner. Inspection should take place in good light with the patient’s arms by her side, above her head, and then pressing on her hips (Fig. 19.2). Skin dimpling or a change of contour is present in a high percentage of patients with breast cancer (Fig. 19.3). Breast palpation is performed with the patient lying flat with her arms above or under her head. All the breast tissue is examined, using the fingertips to detect any abnormality (Fig. 19.4). Any abnormal area is then examined in more detail, to determine the texture and outline of the mass. Deep fixation is assessed by asking the patient to tense the pectoralis major muscle; this is accomplished by asking her to press her hands on her hips. All palpable lesions should be measured with callipers and the size and site (using the clock) recorded in the hospital notes.

Assessment of regional nodes

Once the breast has been palpated, the nodal areas are checked (Fig. 19.5). Clinical assessment of axillary nodes is not always accurate. Palpable nodes can be identified in up to 30% of patients with no clinically significant breast disease, while up to 25% of patients with breast cancer who have no palpable nodes on examination will be found histologically to have metastatic disease in the axillary nodes. Ultrasound is better at assessing axillary nodes than clinical examination. The supraclavicular nodes are best examined from behind.

Imaging

Ultrasonography

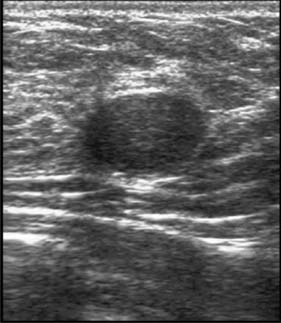

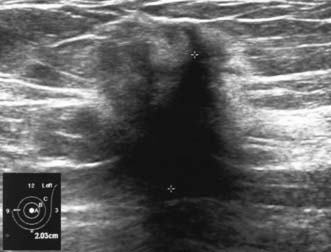

High-frequency waves are beamed through the breast and reflections are detected and turned into images. Cysts show up as transparent objects (Fig. 19.6) and other benign lesions tend to have well-demarcated edges (Fig. 19.7), whereas cancers usually have an indistinct outline and absorb sound, resulting in a posterior acoustic shadow (Fig. 19.8). Ultrasound is also used to assess axillary nodes in patients with breast cancer. Where nodes are enlarged or the cortex of the node thickened, fine needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy should be performed to establish whether nodal metastases are present.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

This is an accurate way of imaging the breast. It has a high sensitivity for breast cancer and may be of value in demonstrating the extent of both invasive and non-invasive disease. It is particularly useful in the conserved breast to determine whether a mammographic lesion at the site of previous surgery is due to scar or to recurrence. It is currently used as a screening tool for high-risk women between the ages of 35 and 50 (EBM 19.1). MRI is the optimum method of imaging breast implants and detecting implant leakage or rupture.

Fine needle cytology and biopsy

Core biopsy

Several cores are removed from a mass or an area of microcalcification by means of a cutting needle technique after injection of local anaesthetic (Fig. 19.9). A 14-gauge needle combined with a mechanical gun produces satisfactory samples and allows the procedure to be performed single-handed. Core biopsy can be performed using palpation to guide biopsy but is most successful when image guidance is employed (ultrasound for mass lesions, stereotactic biopsy for calcifications which are usually impalpable). Vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices allow several large cores to be removed without withdrawing the needle from the breast, and have some advantages when biopsying areas of indeterminate microcalcification detected on screening.

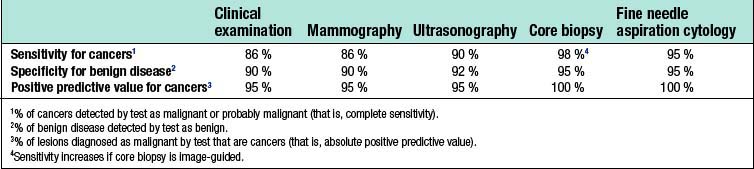

Accuracy of investigations

False-positive results occur with all diagnostic techniques. The sensitivity of clinical examination and mammography varies with age, and only two-thirds of cancers in women under 50 years of age are considered suspicious or definitely malignant on clinical examination or mammography (Table 19.1). Image-guided core biopsy is the most accurate and efficient of the various techniques used to diagnose breast masses.

Disorders of development

Most benign breast conditions occur during development, cyclical activity or involution, and are so common that they are best considered as aberrations rather than true disease (Table 19.2).

Table 19.2 Aberrations of normal breast development and involution

| Age (years) | Normal process | Aberration |

|---|---|---|

| < 25 | Breast development Stromal Lobular |

Juvenile hypertrophy Fibroadenoma |

| 25–40 | Cyclical activity | Cyclical mastalgia Cyclical nodularity (diffuse or focal) |

| 30–55 | Involution | |

| Lobular | Palpable cysts | |

| Stromal | Sclerosing lesions | |

| Ductal | Duct ectasia |

Juvenile hypertrophy

Uncontrolled overgrowth of breast tissue occurs occasionally in adolescent girls, whose breast development initially begins normally at puberty and is followed by rapid breast growth. These changes are usually bilateral, but may be limited to one breast or part of one breast. This process is often referred to as virginal or juvenile hypertrophy (Fig. 19.10). However, it is not hypertrophy, as there is an increase in the amount of stromal tissue rather than in the number of lobules or ducts. This excessive growth is an aberration rather than a true disease, and presenting symptoms are large breasts and pain in the shoulders, neck and back or under the bra straps. Treatment is by reduction mammaplasty.

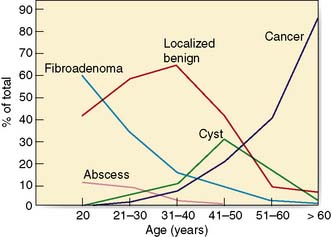

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas are classified in most texts as benign tumours, but are best considered as aberrations of development rather than true neoplasms. The reasons are that fibroadenomas develop from a whole lobule rather than from a single cell, and show hormonal dependence similar to that of normal breast tissue, lactating during pregnancy and involuting in the perimenopausal period. Fibroadenomas are most commonly seen immediately following the period of breast development and growth in the 15–25-year age group (Fig. 19.11). They are usually well-circumscribed, firm, smooth, mobile lumps, and may be multiple or bilateral. Although a small number of fibroadenomas increase in size, most do not and over one-third become smaller or disappear within 2 years. Fibroadenomas have a characteristic appearance with easily visualized margins on ultrasound (Fig. 19.7). Large or giant fibroadenomas (> 5 cm) are infrequent but are more commonly seen in women from certain African countries. Occasionally, a fibroadenoma in an adolescent girl undergoes rapid growth, a condition called juvenile fibroadenoma (Fig. 19.12). Once a diagnosis of fibroadenoma has been established on core biopsy, options for management in lesions measuring less than 4 cm include reassurance with no follow up needed or excision; fibroadenomas over 4 cm in diameter should be excised to ensure that phyllodes tumours are not missed (see below). A carcinoma arising in a fibroadenoma is extremely rare. Patients with simple fibroadenomas are not at significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Disorders of cyclical change

Nodularity

Lumpiness and nodularity in the breast can be diffuse or focal. Diffuse nodularity is normal, particularly premenstrually. In the past, women with lumpy breasts were regarded as having fibroadenosis or fibrocystic disease, but this diffuse nodularity is not associated with any underlying pathological abnormality and so these terms are inappropriate. Focal nodularity is a common cause for women seeking medical advice and is seen in women of all ages (Fig. 19.11). Patients with benign focal nodularity often report that the lump fluctuates in size in relation to the menstrual cycle. Breast cancer should be excluded by imaging +/- core biopsy in women with persistent localized asymmetric areas of nodularity, as breast cancer in younger women often presents as nodularity rather than a discrete mass.

Disorders of involution

Palpable breast cysts

Approximately 7% of women in developed countries develop a palpable breast cyst at some time in their life. Cysts constitute 15% of all discrete breast masses. They are distended, involuted lobules and are most frequently seen in the perimenopausal period (Fig. 19.11). Clinically, they are smooth discrete lumps that can be painful and are sometimes visible. Mammographically, they have characteristic haloes and are easily diagnosed by ultrasonography (see Fig. 19.6). Symptomatic palpable cysts are treated by aspiration and, provided the fluid is not blood-stained, it is discarded. Cysts that contain blood-stained fluid require excision to exclude an associated intracystic cancer. Such cancers are rare and are usually evident on ultrasound. Most cysts are asymptomatic and, following ultrasound assessment, do not need aspiration. All patients with cysts should have mammography, preferably before cyst aspiration, as between 1 and 3% will have a cancer, usually remote from the cyst, visible on mammography (Fig. 19.13). Patients with cysts have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer, but the magnitude of this risk is not considered of clinical significance.

Duct ectasia

The major subareolar ducts dilate and shorten with age; when symptomatic, this is known as duct ectasia. By the age of 70, 40% of women have dilated ducts, some of whom present with nipple discharge or retraction. The discharge is usually cheesy and the retraction is classically slit-like (Fig. 19.14), which contrasts with breast cancer, in which the whole nipple is pulled in (Fig. 19.15). Surgery is indicated if the discharge is troublesome or if the patient wishes the nipple to be everted.

Benign neoplasms

Duct papillomas

These can be single or multiple. They are very common, and should be considered as aberrations rather than true neoplasms as they show minimal malignant potential. They can cause persistent and troublesome nipple discharge, which can be either frankly blood-stained (Fig. 19.16), or serous. Treatment comprises removal of the discharging duct (microdochectomy), which removes the papilloma (if this is the cause) and allows exclusion of an underlying neoplasm, seen in approximately 5% of women who present with a blood-stained nipple discharge.

Phyllodes tumours

Summary Box 19.1 Benign breast disease

• Is more common than breast cancer

• Can be difficult to differentiate from breast cancer

• Inappropriate treatment of benign conditions is associated with significant morbidity

• Occurs against the background of breast development (age < 25), cyclical activity (up to menopause) and involution (following the menopause)

• The only benign condition associated with a significant increased risk of subsequent breast cancer is atypical hyperplasia.

Breast infection

The principles of treating breast infection are:

• Give appropriate antibiotics early to reduce the incidence of abscess formation (Table 19.3)

• If an abscess is suspected, confirm pus is present by ultrasound or aspiration before embarking on surgical drainage

• Exclude breast cancer using imaging and core biopsy in an inflammatory lesion that is solid and that does not settle despite adequate antibiotic treatment.

Table 19.3 Antibiotics most appropriate for treating breast infections*

| Type of infection | No allergy to penicillin | Allergy to penicillin |

|---|---|---|

| Lactating and skin-associated | Flucloxacillin (500 mg 6-hourly) | Clarithromycin (500 mg 12-hourly) |

| Non-lactating | Co-amoxiclav (375 mg 8-hourly) | Combination of clarithromycin (500 mg 12-hourly) with metronidazole (200 mg 8-hourly) |

Lactating infection

Improvements in maternal and infant hygiene have reduced considerably the incidence of infection associated with breastfeeding. When infection does occur, it usually develops within the first 6 weeks of breastfeeding. Presenting features are pain, swelling, tenderness and a cracked nipple or skin abrasion. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism, although Staph. epidermidis and streptococci are occasionally implicated. Drainage of milk from the affected segment is reduced, with the resultant stagnant milk becoming infected. Early infection is treated with flucloxacillin or co-amoxiclav. An established abscess should be treated by recurrent aspiration, or by incision and drainage (Fig. 19.17). Women should be encouraged to breastfeed, as this promotes milk drainage from the affected segment. Rarely, milk flow needs to be stopped using cabergoline, a prolactin antagonist.

Non-lactating infection

Central (periareolar) infection

Treatment of periductal mastitis is with appropriate antibiotics (Table 19.3). Abscesses are managed by aspiration or incision and drainage. Infection is commonly recurrent because treatment does not remove the damaged subareolar duct(s). Following drainage of a non-lactating abscess, up to one-third of patients develop a mammary duct fistula. Recurrent episodes of peri-areolar infection require excision of the diseased duct(s) (total duct excision).

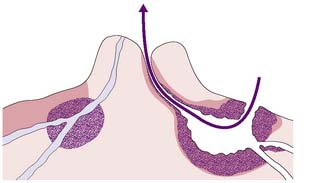

Mammary duct fistula

This is a communication between the skin – usually at the areolar margin – and a major subareolar duct (Fig. 19.18). Treatment is by excision of the fistula and diseased duct(s) under antibiotic cover.

Peripheral non-lactating abscesses

These are less common than periareolar abscesses and are sometimes associated with an underlying condition, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, steroid treatment, granulomatous lobular mastitis or trauma. Infection associated with granulomatous lobular mastitis can be a particular problem, as there is a strong tendency for this condition to persist and recur despite surgery. Peripheral abscesses should be treated by recurrent aspiration with antibiotics (Table 19.3), or incision and drainage under local anaesthesia.

Summary Box 19.2 Breast infection

• Antibiotics should be given early to reduce abscess formation

• Hospital referral is indicated if infection does not settle rapidly on antibiotics

• If an abscess is suspected, this should be confirmed by ultrasound or aspiration

• If the lesion is solid on ultrasound or aspiration a core biopsy should be performed to exclude an underlying inflammatory carcinoma.

Skin-associated infection

Primary infection of the skin most commonly affects the lower half of the breast and can be recurrent in women who either are overweight or have large breasts. It is more common after previous surgery or radiotherapy. Treatment is with antibiotics (Table 19.3) and drainage or aspiration of abscesses. Women with recurrent infection should be advised about weight reduction and keeping the area as clean and dry as possible.

Breast cancer

Epidemiology

Over 1 million new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed each year world-wide. It is the most common malignancy in women comprising 18% of all female cancers. In the UK, approximately 1 in 9 women will develop breast cancer. Known risk factors are shown in Table 19.4.

Table 19.4 Established and probable risk factors for breast cancer

| Factor | Relative risk | High-risk group |

|---|---|---|

| Age | > 10 | Elderly |

| Geographical location | 5 | Developed country |

| Age at first full pregnancy | 3 | First child in early 40s |

| Previous benign disease | 4–5 | Atypical hyperplasia |

| Cancer in other breast | > 4 | Women treated for breast cancer |

| Socioeconomic group | 2 | Social classes I and II |

| Diet | 1.5 | High intake of saturated fat |

| Exposure to ionizing radiation | 3 | Abnormal exposure in young females after age 10 |

| Taking exogenous hormones | ||

| Oral contraceptives | 1.24 | Current use |

| Combined hormone replacement therapy | 2.3 | Use for ≥ 10 years |

| Family history | ≥ 2 | Breast cancer in first-degree relative |

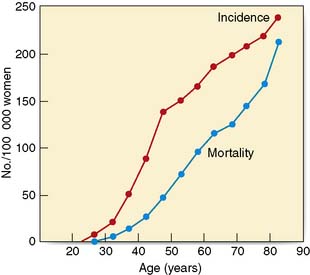

The incidence of breast cancer increases with age, doubling every 10 years until the menopause, when the rate of increase slows dramatically (Fig. 19.19). Compared with lung cancer, the incidence of breast cancer is higher at young ages. There is a variation in incidence by up to a factor of 5 between different countries. Studies of migrants from Japan, a low-risk area, to Hawaii show that the rate of breast cancer in migrants becomes the same as the rate in the host country within one or two generations. This suggests that environmental rather than genetic factors are important in the aetiology. Women who start menstruating early in life, or who have a late menopause, have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer. Young age at first delivery protects against breast cancer. The risk of breast cancer in women who have their first child after the age of 30 is twice that of women who have their first child before the age of 20. Breast cancer is also increased in nulliparous women, who have a risk approximately 2.4 times that of women having their first child before the age of 20. The highest risk is in women who have a first pregnancy over the age of 40 years. Breastfeeding has a small protective effect and women who have breastfed have a slightly reduced incidence of breast cancer.

Severe atypical hyperplasia carries a four- to five-fold higher risk of breast cancer than when no proliferative changes are evident. A doubling of breast cancer was observed among teenage girls exposed to radiation during the Second World War. Women treated by radiation therapy for lymphoma during adolescence and teenage years are also at significant risk of developing early-onset breast cancer. Although there is a close correlation between the incidence of breast cancer and dietary fat intake in populations, the relationship is neither particularly strong or consistent. A high alcohol intake does appear to increase breast cancer risk. Patients taking the oral contraceptive pill have a 1.24 times increased relative risk of breast cancer compared to that of the general population. This rapidly falls to normal after stopping the pill. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increases breast cancer risk. Combined oestrogen and progestogen HRT is associated with a greater risk than preparations containing oestrogen alone (Table 19.5).

Table 19.5 Relationship of HRT to breast cancer development: relative risk of breast cancer related to type and recency of HRT use*

| Patient group | Relative risk (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|

| Never used HRT | 1.0 (0.96–1.04) |

| All previous users Current users of: | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

| Oestrogen only+ | 1.3 (1.22–1.38) |

| Oestrogen/progestogen combinations | 2.0 (1.91–2.09) |

+ Data from WH1 study suggest risk is lower from oestrogen only than combined HRT and may not exceed 1.

Types of breast cancer

Non-invasive

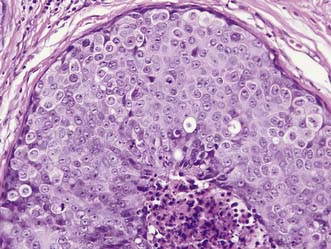

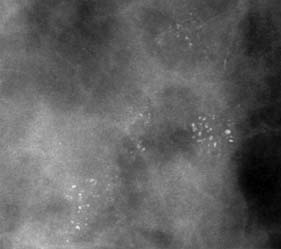

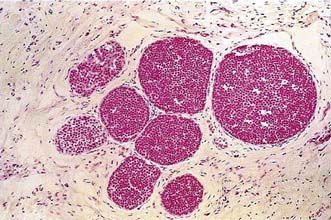

Two main types of non-invasive cancer can be recognized on the basis of cell type. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is the most common form (Fig. 19.20), making up to 3–4% of symptomatic and 17–25% of screen-detected cancers. Screen-detected DCIS is most commonly associated with microcalcifications on mammograms (Fig. 19.21), which can be either localized or widespread. Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) (Fig. 19.22) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) have been combined into a single diagnostic condition called lobular intraepithelial neoplasia (LIN). This is usually an incidental finding and is generally treated by regular follow-up, as these women are at significant risk of developing invasive cancer in either breast.

Screening for breast cancer

Randomized controlled trials have shown that screening by mammography can significantly reduce mortality from breast cancer (EBM 19.2). Mortality is reduced by up to 40% in women who attend for screening, with the greatest benefit being seen in women aged over 50. To be effective, attendance at screening programmes has to be greater than 70%. The UK programme screens the 50–70-year age group but may extend from 47–73 over the next decade.

About two-thirds of screen-detected abnormalities are shown to be benign or normal on further mammographic or ultrasound imaging. Among women aged 50–70, approximately 75 cancers (invasive and non-invasive) are detected for every 10 000 attending for their initial screen. At subsequent screens, approximately 50 cancers should be identified for every 10 000 attenders. Up to 70% of important abnormalities are impalpable, and for these, image-guided (ultrasound or stereotactic radiography) core biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis. Compared with symptomatic cancers, screen-detected cancers are smaller and more likely to be non-invasive. The ability of screening to influence mortality from breast cancer (EBM 19.3) indicates that early diagnosis identifies cancers at an earlier stage of evolution, when metastasis is less likely to have occurred.

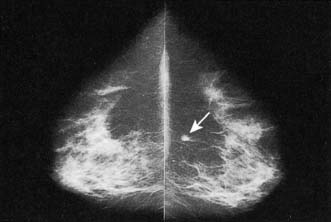

Mammographic features of breast cancer

Mammographically, a cancer most commonly appears as a dense opacity with an irregular outline from which spicules pass into the surrounding tissue (Fig. 19.23). Associated features include microcalcifications, which can occur within or outside the lesion, skin tethering or thickening, distortion of the shape of the breast or overlying skin, and tenting or direct involvement of underlying muscle. Involved lymph nodes can also sometimes be seen (Fig. 19.24). Microcalcification alone is a feature of DCIS.

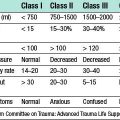

Staging

When invasive cancer is diagnosed, the extent of the disease should be assessed. The currently used TNM (tumour, nodes and metastases) system depends on clinical measurements and clinical assessment of lymph node status, both of which are inaccurate (Table 19.6). To improve the TNM system, a separate pathological classification has been added. Patients with small breast cancers (< 4 cm) have a low incidence of detectable metastatic disease and, unless they have specific symptoms, should not undergo investigations to search for metastases other than in the axilla which can be assessed by ultrasound and/or FNAC or core biopsy. Patients with larger or more locally advanced breast cancers are more likely to have metastases and should be considered for bone scan and liver ultrasound. A simpler classification of breast cancer separates patients into three groups: operable, locally advanced and metastatic.

| T (Primary tumour) | ||

| • | TX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

| • | T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

| • | T1s | Carcinoma in situ: intraductal carcinoma, lobular carcinoma in situ, or Paget’s disease of the nipple with no associated tumour mass1 |

| • | T1 | Tumour 2.0 cm or less in greatest dimension2 |

| • | T1a | 0.5 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| • | T1b | More than 0.5 cm but not more than 1.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| • | T1c | More than 1.0 cm but not more than 2.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| • | T2 | Tumour more than 2.0 cm but not more than 5.0 cm in greatest dimension2 |

| • | T3 | Tumour more than 5.0 cm in greatest dimension2 |

| • | T4 | Tumour of any size with direct extension to chest wall or skin |

| • | T4a | Extension to chest wall |

| • | T4b | Oedema (including peau d’orange), ulceration of the skin of the breast or satellite nodules confined to the same breast |

| • | t4c | Both of the above (T4a and T4b) |

| • | T4d | Inflammatory carcinoma |

| N (Regional lymph nodes) | ||

| • | NX | Cannot be assessed (e.g. previously removed) |

| • | N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| • | N1 | Movable ipsilateral axillary lymph node(s) |

| • | N2 | Ipsilateral lymph node(s) fixed to one another or to other structures |

| • | N3 | Ipsilateral internal mammary lymph node(s) |

| M (Distant metastases) | ||

| • | MX | Cannot be assessed |

| • | M0 | No distant metastasis |

| • | M1 | Distant metastasis present (includes metastasis to ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes) |

Note: Chest wall includes ribs, intercostal muscles and serratus anterior muscle, but not pectoral muscle.

1 Paget’s disease associated with tumour mass is classified according to the size of the tumour.

2 Dimpling of the skin, nipple retraction or other skin changes may occur in T1, T2 or T3 without changing the classification.

The curability of breast cancer

Prognostic factors

Factors related to prognosis include:

• the stage of the tumour at diagnosis: principally, its size and the involvement of the axillary lymph nodes or the presence of clinically evident metastases

• biological factors that relate to tumour aggressiveness: these include histological grade, histological type, the presence of lymphatic or vascular invasion, hormone receptor content and HER2 status (see above).

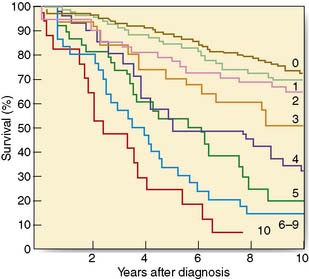

The single most important prognostic factor is the number of axillary lymph nodes involved (Fig. 19.25). It is possible to combine prognostic factors to form an index that allows the identification of groups with different prognoses. The Nottingham Prognostic Index (Table 19.7) is the most widely used and incorporates three factors: tumour size, node status and histological grade.

• Tumour size (pathological size of lesion in centimeters)

• Node status (scored 1 if no nodes involved, 2 if 1–3 nodes positive, 3 if ≥ 4 nodes involved)

• Grade I tumours (scored as 1) grade II (scored as 2) grade III (scored as 3).

| NPI = (0.2 × size in cm) + lymph node stage (score 1 for no nodes, 2 for 1-3 nodes, 3 for ± 4 nodes) + grade (score 1 for grade I, 2 for grade II, 3 for grade III) Originally, the NPI was used to divide women into good, intermediate or poor prognostic groups; several confirmatory studies have led to a refined NPI with five categories |

| Group | Index value | 10-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent (EPG) | ≤ 2.4 | 98 |

| Good (GPG) | ≤ 3.4 | 90 |

| Moderate I (MPGI) | ≤ 4.4 | 83 |

| Moderate II (MPGII) | < 5.4 | 75 |

| Poor (PPG) | > 5.4 | 47 |

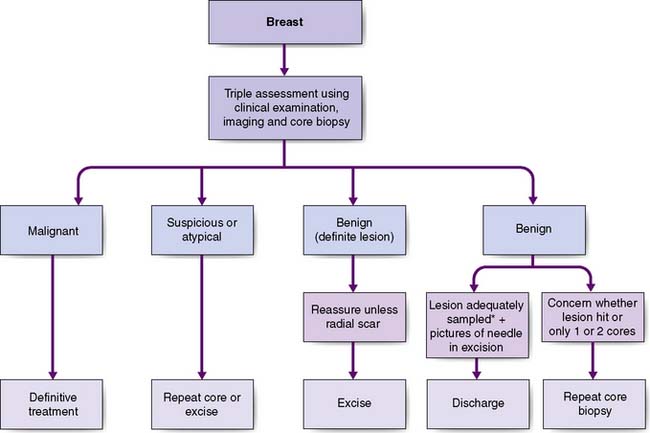

Presentation of breast cancer

The most common presentation is with a breast lump or lumpiness, which is usually painless. Any discrete lump, no matter how small or mobile, can be a cancer. The investigation of a breast lump is shown in Figure 19.26. Malignant lesions may be firm and irregular and produce visible signs of breast asymmetry, such as flattening, dimpling or puckering of the overlying skin, or retraction or alteration in nipple contour. Approximately 50% of breast cancers are located in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Diagnosis of breast lumps is a particular problem in young women, in whom the breasts are dense and lumpier and cancer is rare. Some patients present with features of locally advanced breast cancer such as skin ulceration, with direct infiltration of the skin by tumour or with oedema (Fig. 19.27) of the overlying skin.

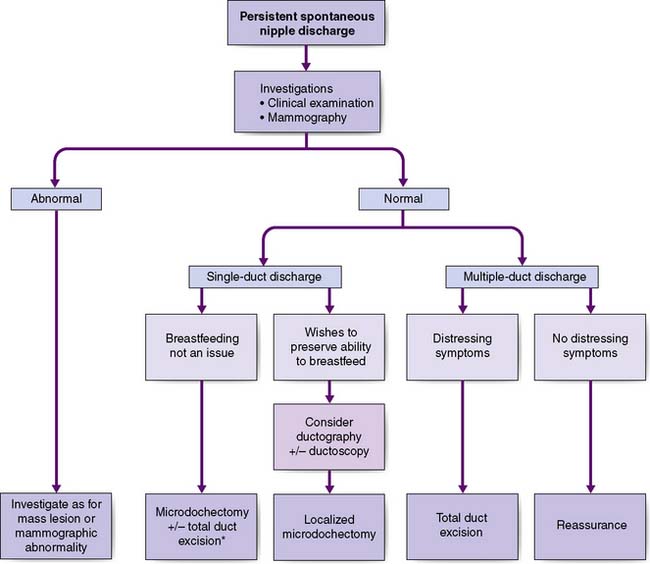

Breast pain alone is a rare presenting feature of breast cancer; 2.7% of patients with breast pain have cancer, whereas 4.6% of patients presenting with breast cancer have pain as their only symptom. Nipple discharge, which is either blood-stained or contains moderate or large amounts of blood on testing, can be a presenting feature of breast cancer. However, only 5–10% of patients with this symptom will have underlying malignancy. Investigation of patients who present with nipple discharge is shown in Figure 19.28. Patients with breast cancer occasionally present with a dry scaling or red weeping appearance of the nipple known as Paget’s disease; this signifies an underlying invasive or non-invasive cancer (Fig. 19.29) and should be differentiated from eczema (Fig. 19.30). Paget’s disease always affects the nipple and only involves the areola as a secondary event, whereas eczema primarily involves the areola and only secondarily affects the nipple. Approximately 1–2% of patients with breast cancer present with Paget’s disease. In half of these, it is associated with an underlying mass lesion, and 90% of such patients will have an invasive cancer. Of the patients without a mass lesion, 30% have an invasive cancer and the rest have in situ disease alone.

Management of operable breast cancer

In situ breast cancer

Summary Box 19.3 Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

• Localized disease is treated by wide local excision to clear margins

• All patients other than those at low risk of recurrence should be considered for adjuvant radiotherapy to the breast following wide local excision

• Tamoxifen reduces all breast cancer events following wide excision, but its exact role in reducing local recurrence following conservative treatment is not clear

• The value of aromatase inhibitors is being investigated

• Large areas of DCIS are usually treated by mastectomy ± reconstruction.

Operable breast tumours

Operable breast tumours are those restricted to the breast or associated with mobile axillary lymph nodes on the same side: T1, T2, T3, N0, N1, M0. As only a minority of patients are cured by locoregional treatments alone, all should be considered for systemic therapy after local therapy (EBMs 19.4 and 19.5M).

Local therapy

There are currently two accepted methods of local therapy for operable breast cancer.

Breast-conserving treatment (wide local excision and radiotherapy)

Summary Box 19.4 Breast conservation

• Suitable for localized, operable breast cancers in which there is no evidence of metastatic disease beyond regional nodes; excision must leave a reasonable cosmetic result to produce benefits compared with mastectomy

• Includes wide local excision of the cancer to clear histological margins, axillary surgery (sentinel node biopsy, or clearance of the axillary nodes) and whole-breast radiotherapy consisting of a 45–50 Gy dose of radiotherapy applied to the whole breast, with an optional 10–15 Gy boost to the tumour bed.

Mastectomy

This is an alternative method of local treatment. It is indicated in patients:

• for whom radiotherapy is not available or when there is a wish to avoid radiotherapy

• who elect to have a mastectomy

• who have more than one focus of cancer in their breast and where removal of all the cancers would produce an unacceptable cosmetic result

• who have a localized invasive cancer but a large area of surrounding non-invasive disease

• when breast conservation would produce an unacceptable cosmetic result. (This includes some central lesions directly underneath the nipple, and most cancers measuring more than 4 cm in diameter.) Breast-conserving surgery is possible in these women if they have shrinkage following initial systemic therapy, or if the breast defect is filled with a latissimus dorsi flap (Fig. 19.31).

Summary Box 19.5 Mastectomy

• Is appropriate for large operable breast cancers or in patients with extensive non-invasive disease, an incomplete excision after attempted breast-conserving surgery or some women with central tumour

• Consists of total removal of the breast together with sentinel node biopsy, axillary node sampling or axillary clearance

• Should be followed by chest-wall radiotherapy in those women identified to be at significantly increased risk of local recurrence.

Systemic therapy

Systemic treatment may be given as adjuvant therapy after surgery and/or radiotherapy, or as primary or neoadjuvant treatment before surgery and/or radiotherapy. The effectiveness of adjuvant treatment has been shown in clinical trials (EBM 19.6). Randomized studies comparing primary systemic treatment with adjuvant treatment have shown similar survivals, with a higher rate of breast-conserving surgery in patients having initial medical treatment. Adjuvant treatments consist of chemotherapy or hormonal therapy.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

A combination of drugs is more effective than a single agent and the optimal benefit seems to come from at least four cycles of postoperative chemotherapy. The benefits of chemotherapy are greatest in women under the age of 50 (Table 19.8); a smaller but still significant benefit is seen in older women. Regimens that include anthracyclines are more effective than non-anthracycline containing regimens. Commonly used regimens include AC (adriamycin, cyclophosphamide) or FEC (5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide) alone, or four courses of epirubicin alone, or FEC followed by four courses of CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil). The taxanes (taxol and taxotere) combined with an anthracycline such as AT (adriamycin, taxotere/taxol) or ET (epirubicin and taxotere/taxol) appear more effective than anthracyclines alone.

Table 19.8 Reduction in recurrence and mortality in polychemotherapy trials

| Age | Reduction in annual odds of recurrence (% ± SD) | Reduction in annual odds of death (% ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| < 40 | 37 ± 7 | 27 ± 8 |

| 40-49 | 34 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 |

| 50–59 | 22 ± 4 | 14 ± 4 |

| 60–69 | 18 ± 4 | 8 ± 4 |

| All ages | 23 ± 8 | 15 ± 2 |

Adjuvant anti-HER2 therapy

Overall, 15–20% of cancers over-express the oncogene HER2 and these cancers have a worse prognosis than those that are HER2-negative. A humanized monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab) has been shown to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence by up to 50% in women whose cancers over-express HER2 (EBM 19.7).

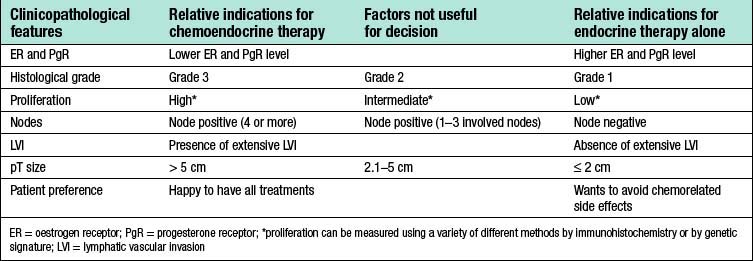

Studies with lapatanib, an oral agent which targets HER1 and HER2 are in progress. Adjuvant systemic therapy is effective in patients at both low and high risk of recurrence, but the absolute gains in survival are greatest in the latter. Risk of recurrence can be calculated using the Nottingham Prognostic Index (see Table 19.7) or can be based on individual factors. Adjuvantonline.com® presents absolute benefits in individual patients from different endocrine and chemotherapy regimens. An outline of the use of adjuvant treatment in different groups and factors which should be taken into consideration are presented in Tables 19.9 and 19.10.

Table 19.9 Indications and factors helpful in deciding whether ER-positive HER2-negative breast cancer should be treated with chemo and endocrine therapy combined, or endocrine therapy alone

Table 19.10 Suggested adjuvant treatment for patients with breast cancer1

| Risk group | Premenopausal | Postmenopausal |

|---|---|---|

| Very low-risk | Nil or tamoxifen | Nil or tamoxifen |

| Low-risk ER+ | Tamoxifen ± OS2 | Tamoxifen |

| Low-risk ER- | Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy |

| Moderate-risk ER+ | Chemotherapy + tamoxifen ± OS | Chemotherapy + AI/tam3 |

| Moderate-risk ER- | Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy |

| High-risk | Chemotherapy + tamoxifen + OS (if ER+) | Chemotherapy + AI/tam3 |

(ER = oestrogen receptor)

1 Patients whose tumours over-express HER2 should also be considered for adjuvant trastuzumab.

2 Ovarian suppression (OS): either luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) analogue or surgical oophorectomy.

3 With the data showing superiority of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) over tamoxifen, the former are being increasingly used either as first-line treatments in high-risk women or in sequence with tamoxifen.

Psychological aspects

There is evidence that patients benefit psychologically from immediate breast reconstruction. Options for reconstruction include the placement of an implant behind the chest wall muscles at the time of mastectomy. The problem with this approach is that the size of implant that can be inserted is limited and symmetry is difficult to obtain. Another option is to place a tissue expander behind the pectoral muscles. The use of implants has increased because larger pockets can now be created by the use of decellularized human or pig skin sutured from the pectoralis major to the chest wall to create a larger pocket into which an implant or expander can be placed. Small amounts of fluid are injected regularly into an expander over a period of months before replacing it, at a second operation, with a permanent prosthesis. Alternative options include using myocutaneous flaps; the most commonly used are the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap with or without an implant (Fig. 19.31), and the rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap alone.

Management of locally advanced breast cancer

Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) is characterized by features suggesting infiltration of the skin or chest wall by tumour or matted involved axillary nodes (Table 19.11). It has a variable natural history, with reported 5-year survivals of between 1 and 30%. The median survival was previously about 2–2.5 years but this has improved with better systemic therapy. LABC can arise because of its position in the breast (for example, peripheral), neglect (some patients do not present to hospital for months or years after they notice a mass) or biological aggressiveness. The latter includes inflammatory cancers that present with erythema and/or widespread peau d’orange affecting the breast skin. The peau d’orange is because of lymphatic obstruction by cancer cells in lymphatics or in lymph nodes (see Fig. 19.27). Inflammatory carcinomas are uncommon and are characterized by brawny, oedematous, indurated and erythematous skin changes (Fig. 19.32). They have the worst prognosis of all LABCs.

Table 19.11 Clinical features of locally advanced breast cancer

| Skin |

Local and regional relapse was formerly a major problem in LABC and affected more than half of patients. By treating patients initially with systemic therapy, followed by surgery and radiotherapy or radiotherapy alone, improvements in local control have been achieved. Systemic treatment consists of either chemotherapy (inflammatory cancers, oestrogen receptor-negative tumours and rapidly progressive disease) or hormonal treatment (slow or indolent disease, oestrogen receptor-positive cancers, or women who are elderly or unfit). Following systemic therapy, the disease may become operable, at which point surgery, usually mastectomy, is followed by radiotherapy. In women whose disease remains inoperable following systemic treatment, radiotherapy is given. This is followed by surgery in some women in whom viable resectable cancer remains following radiotherapy (Fig. 19.32). Systemic therapy, either chemotherapy (for 3–4 months) or hormone treatment (usually for 5 years), is often given after surgery.

Summary Box 19.7 Locally advanced breast cancer

• For the majority, consider systemic chemotherapy or, in the elderly or those who have indolent hormone-sensitive cancers, prescribe hormonal therapy

• Radiotherapy can be used following primary chemotherapy, or can be given concurrently with hormonal therapy

• Consider surgery if the disease becomes operable following primary systemic therapy, or in patients with locally advanced breast cancers that have occurred because of either a delay in diagnosis or their position in the breast, e.g. superficial or at the breast margin. Surgery is also possible in those with locally advanced disease following radiotherapy.

Management of metastatic or advanced breast cancer

Hormonal treatment

A variety of hormonal interventions are available for use in metastatic breast cancer (Table 19.12). In premenopausal women these include oophorectomy (surgical, radiation- or drug-induced by GnRh analogues) combined with tamoxifen. Options in postmenopausal women include the new aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane) and the progestogens (such as medroxyprogesterone acetate or megestrol acetate). First-line treatment is with letrozole or anastrozole. Objective responses to hormonal treatments are seen in 30% of all patients and in 50–60% of those with oestrogen receptor-positive tumours. Response rates of 25% are seen when using second-line hormonal agents, although fewer than 15% of patients who show no response to first-line treatment will have a response to second-line agents. Approximately 10–15% of patients respond to third-line endocrine agents.

| Premenopausal |

Note These agents can be used in any order.

1 There is evidence that combined ovarian suppression plus an anti-oestrogen is superior to single-agent treatment in premenopausal women.

2 Letrozole or anastrozole are first-line agents in postmenopausal women. Data for letrozole is more impressive than for anastrozole.

3 A steroidal aromatase inhibitor (e.g. exemestane) can have efficacy even if a tumour is resistant to the non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors letrozole and anastrozole.

4 Licensed in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, but not Scotland; continues to be evaluated in trials.

Anti-HER2 therapy

Summary Box 19.8 Metastatic breast cancer

• The primary aim is to improve symptoms as well as improving the quantity and quality of life

• Consider hormone therapy if there is a long disease-free interval and the tumour is hormone receptor-positive

• Consider chemotherapy if there is a short disease-free interval, vital organs are affected and/or the tumour is oestrogen receptor-negative.

Specific problems

Brain metastases

Summary Box 19.9 Metastatic disease: specific problems

• Bone metastases may require local radiotherapy, bisphosphonates or orthopaedic intervention, combined with systemic hormonal therapy or chemotherapy

• Hypercalcaemia causes nausea, constipation, thirst, polyuria, weakness, pain and personality change, and is treated by rehydration followed by bisphosphonates

• Spinal cord compression should be treated by surgical decompression if appropriate, or by steroids and radiotherapy

• Pleural effusions should be treated by tube drainage, followed by instillation of bleomycin, tetracycline or talc

• Discrete lung metastases may not cause acute symptoms but lymphangitis carcinomatosa can cause severe bronchospasm and dyspnoea, which may be relieved by steroids, bronchodilators and chemotherapy

• Liver metastases present most commonly with general debility, nausea and lack of appetite; they are usually treated by chemotherapy but hormone therapy with aromatase inhibitors is an option in postmenopausal women with ER+ rich cancers

• Brain metastases are treated initially with steroids, followed by radiation. Surgery can be used for isolated single metastases.

MALE BREAST

Gynaecomastia

Gynaecomastia (the growth of breast tissue in males to any extent in all ages) is entirely benign and usually reversible. It commonly occurs at puberty and in old age and is seen in 30–60% of boys aged 10–16. In this age group it usually requires no treatment, as 80% resolve spontaneously within 2 years (Fig. 19.33). Embarrassment or persistent enlargement is an indication for surgery. Senescent gynaecomastia usually affects men between 50 and 80, and in most cases does not appear to be associated with any endocrine abnormality. Causes include excess alcohol intake and drugs including cannabis, cirrhosis, hypogonadism and, rarely, testicular tumours. Rapidly progressive gynaecomastia is an indication for an assessment of hormonal profile. A history of recent progressive breast enlargement without pain and tenderness, or an easily identifiable cause, should raise the suspicion of breast cancer. If there is a localized mass, then further investigations should be performed. Surgery consists of excision of glandular tissue combined with liposuction or liposuction alone and is reserved for patients with significant social embarrassment.