Chapter 40 The breast

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women, and affects 1 woman in 8 in the USA, usually after the age of 50. Those women at greater risk of developing breast cancer are summarized in Box 40.1. Early detection is the only way to control the disease, as by the time the cancer can be palpated easily, spread is likely to have occurred.

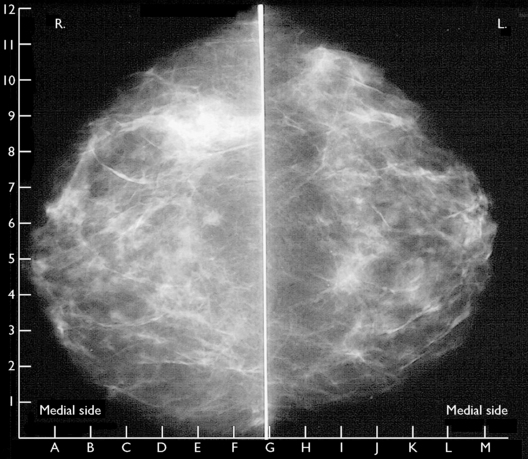

For this reason, programmes to persuade women to learn and practise breast self-examination have been developed in many countries (see p. 2). In addition, health authorities recommend that women over 35 have an annual breast examination by a doctor. This should be supplemented by mammography between the ages of 40 and 45, then annually from the age of 50 (Fig. 40.1). Two views should be taken, as this increases the detection of breast cancer and reduces recall rates. About 95% of women who have mammographic and clinical screening will have no evidence of breast cancer, 5% will require further investigation, and 1% will need biopsy to establish or exclude breast cancer. In women at high risk (Box 40.1), MRI has been shown to have a high sensitivity for detection of malignancy particularly in women younger than 40 years.