The Breast

Anatomy of the Female Breast

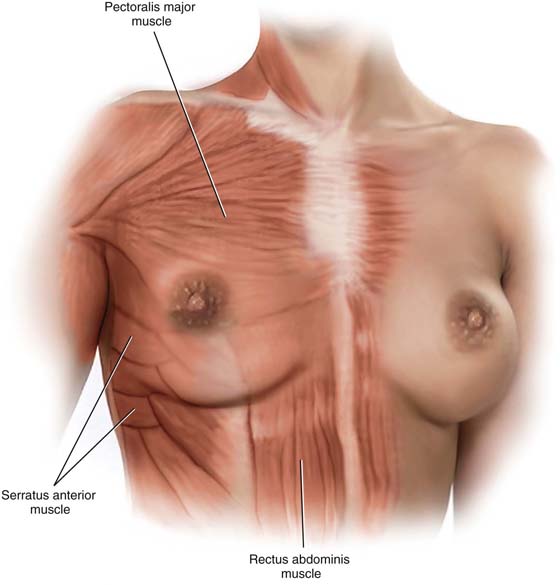

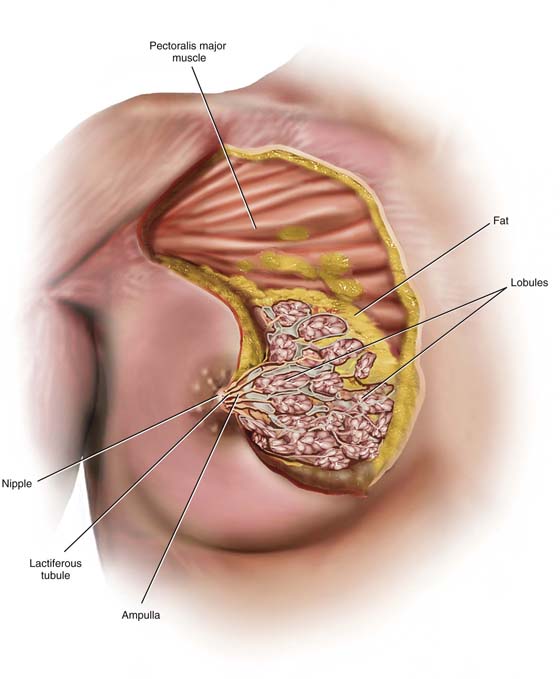

The breasts are modified sweat glands and specifically function as modified apocrine glands. They represent significant gender-identifying structures, which society and the individual connote as phenotypically female. Mature adult breasts occupy a prominent position on the anterior chest wall between the second and sixth ribs (Fig. 105–1A). The “average” breast measures 10 to 12 cm in diameter and is 5 to 7 cm in thickness. Across the chest wall, the breast extends from the margin of the sternum to the midaxillary line. A portion of breast tissue projects into the axilla. This entity is known as the tail of Spence (Fig. 105–1B). Anatomically, the entire breast lies between the superficial and deep layers of the superficial pectoral fascia. The latter is contiguous with Scarpa’s fascia of the anterior abdominal wall. Thus, the breast is roughly hemispherical in shape and sits on top of the deep pectoral fascia, which in turn encompasses the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 105–2). A significant factor in the maintenance of the structure and shape of the breasts is attributed to fibrous bands that course between the deep and superficial layers of fascia. These dense Cooper’s ligaments form the so-called suspensory ligaments of the breast, which are particularly prominent at its lower portion (inframammary fold).

The tissues lying between the deep and superficial layers of the superficial pectoral fascia consist mainly of fat but additionally of breast parenchyma and connective tissue (stroma). The relative amount of natural fat content contributes to the bounce of the breast with movement. As the volume of fat increases, so does the motion of the breasts, but only to the point where the quantity of fat produces such a large mass that it results in drooping, pendulous breasts. Scarring secondary to artificial augmentation of the breasts also diminishes the natural movement of the breasts on the chest wall (Fig. 105–3).

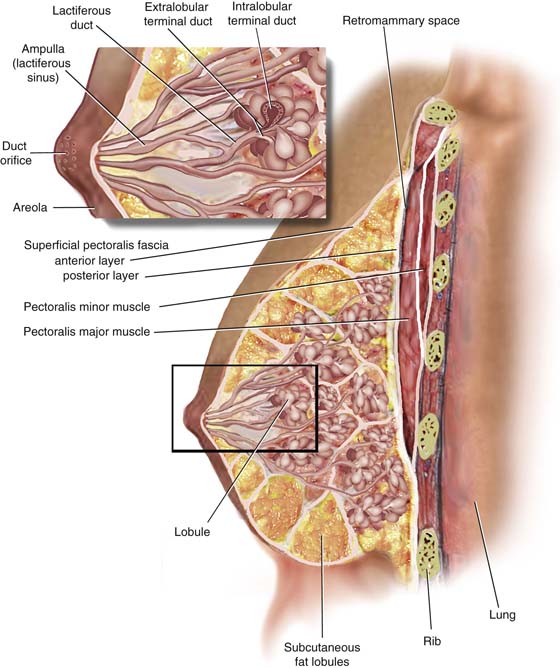

The breast parenchyma is divided into 15 to 20 segments or glandular units or lobes, which are radial in arrangement and converge to a series of ducts on the nipple. Approximately 5 to 10 major collecting ducts open at the nipple. Each duct drains a segment or lobe of the breast. Each lobe contains 20 to 40 lobules. Each lobule in turn consists of between 10 and 100 alveoli (Figs. 105–3 and 105–4).

Mounted on each breast is a more deeply pigmented circular area measuring an inch or more in diameter—the areola. The nipple caps the center of the areola. The dermis of the areola contains longitudinal and circular smooth muscle, which creates a wrinkled appearance when the muscles contract (see Fig. 105–1B, inset).

Several elevated openings may be observed on the periphery of the areola. These are the termini of the ducts of Montgomery’s glands. The latter are modified sebaceous glands whose secretions keep the areolae lubricated and supple. During pregnancy, these same glands may secrete a milklike substance (see Fig. 105–1B, inset).

The functioning unit of the breast is the lobular unit. This consists of small glands lined by cuboidal and myoepithelial cells surrounded by a vascular stroma. Small interlobular terminal ducts lead to extralobular terminal ducts, which in turn lead to larger collecting ducts and then lead to still larger lactiferous ducts that drain entire lobes. Before draining into the nipple, these ducts dilate to form a lactiferous ampulla or sinus. Contraction of the myoepithelial cells as well as the smooth muscle of the areola aids in emptying the lactiferous sinuses of milk (see Fig. 105–4, inset).

Breast volume changes during the menstrual cycle. The breast parenchyma responds to stimulation with estrogen and progesterone. Similarly, water content within the fat (edema) parallels that seen within the endometrium, with peaks between days 22 and 25. The least amount of hormonal alteration occurs during the 4 to 5 days after the onset of menstrual flow.

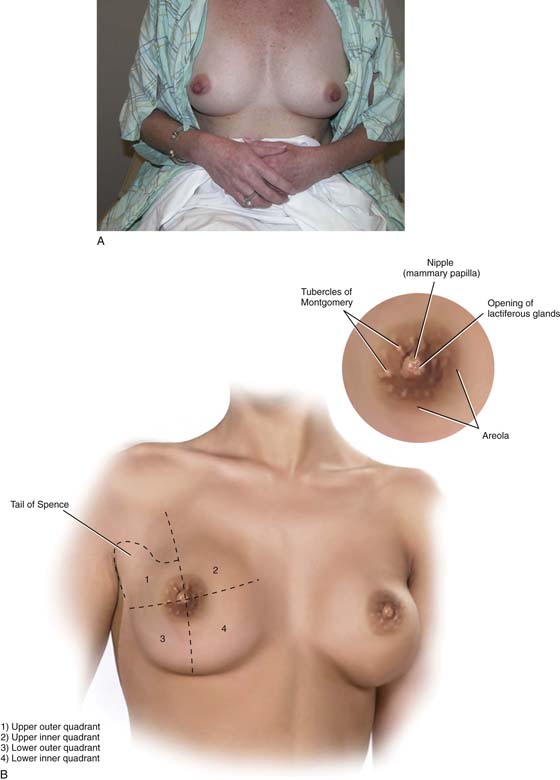

Finally, although most breasts appear roughly symmetrical in size (volume), differences between the left and right breasts are common (Fig. 105–5).

FIGURE 105–1 A. The mammary glands occupy a prominent location on the female chest wall. Phenotypically, they connote female gender to the individual. B. The breasts occupy space on the anterior chest wall between the second and sixth ribs. For purposes of description, the breasts are divided into four quadrants—two upper and two lower. The sculpted lower edge of the hemispheric breast is formed by the inframammary ridge. A portion of the breast tissue in the upper outer quadrant extends into the axilla (tail of Spence). The inset shows details of the areola, which encompasses the nipple, the tubercles of Montgomery, and the pigmented skin highlighting this area.

FIGURE 105–2 The breasts are contained within the superficial pectoral fascia and lie on the deep fascial layer that encloses the pectoralis major muscle. The breast encroaches inferiorly on the deep fascia of the serratus anterior, external oblique, and rectus abdominis muscles. The superficial pectoral fascia is subdivided into superficial and deep layers. The deep superficial layer is distinctly separated from the deep pectoral fascia by loose fat.

FIGURE 105–3 The breast consists of fat and breast tissue. The latter is made up of lobules, ducts, and fibrous connective tissue. The apocrine glandular tissues or lobules secrete milk, which is collected and transported via a series of ducts to the nipple. The structural architecture of the breast is maintained by fibrous bands traveling between the deep superficial fascia and the dermal component of the breast’s skin. These connective tissue bands or Cooper’s ligaments largely account for the breast’s spherical shape.

FIGURE 105–4 The functioning unit of the breast is made up of small glands lined by cuboidal and myoepithelial cells, which elaborate a milky secretion. The secretion is propelled through intralobular and extralobular terminal ducts to larger lactiferous collection ducts. Before draining into the nipple, the secretions are stored in ampullary ducts (sinuses). Each duct drains a lobe consisting of 20 to 40 lobules.

FIGURE 105–5 This picture demonstrates rather extreme developmental asymmetry between the right and left breasts. Some slight size difference between the two breasts is not uncommon, and in contrast to the case illustrated here, the left breast is usually mildly larger than the right.

Clinical Breast Examination

The breast examination is an integral part of the annual gynecologic examination for all women. This portion of the examination is an important screening tool for the detection of breast cancer. As with any physical examination, the end result, that is, early detection of a breast lump, depends on the quality and thoroughness of the examination. Sufficient time must be allocated to its performance, so the physician does not rush through this important component.

The ideal time period for the performance of a breast examination is during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. For a woman receiving hormonal replacement, the best time for the examination is 4 to 5 days after the last pill is taken.

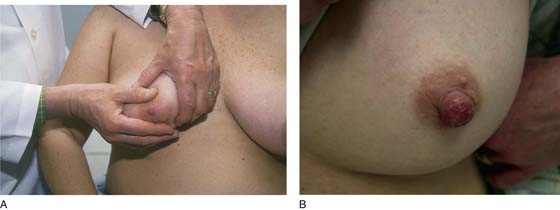

The examination begins with the patient sitting at the end of the examination table facing the examiner (Fig. 105–6). With the patient’s hands at her side, the breasts are observed for symmetry, retraction, and dimpling (Fig. 105–7). The color of the skin of the breasts is observed, inspecting particularly for redness, fixation, and scar formation. The areola and nipples are checked for inversion, dimpling, discoloration, and ulceration. The patient is asked to lean forward, which frees the breasts from the chest and accentuates pendulousness (see Fig. 105–7).

Next, the patient is asked to place her hands on her hips (Fig. 105–8). This move causes the pectoralis major muscle to contract. The patient next stretches her arms overhead, which elevates the breasts against the chest wall (Fig. 105–9). Similar observations are made in this position.

As noted in the anatomy section, most often the difference in breast volume is small; occasionally, the size difference between left and right breasts (i.e., asymmetry) is extreme (see Fig. 105–5).

While the patient remains seated, the axillary exam is performed on the right and left sides (Fig. 105–10). The patient’s right arm is supported by the examiner’s right arm, and the left hand palpates the axillary lymph nodes. The supraclavicular area is likewise palpated for adenopathy (Fig. 105–11). The procedure is then carried out on the left side. Next, the examiner stands behind the patient and compresses the breast and nipple for discharge (Fig. 105–12).

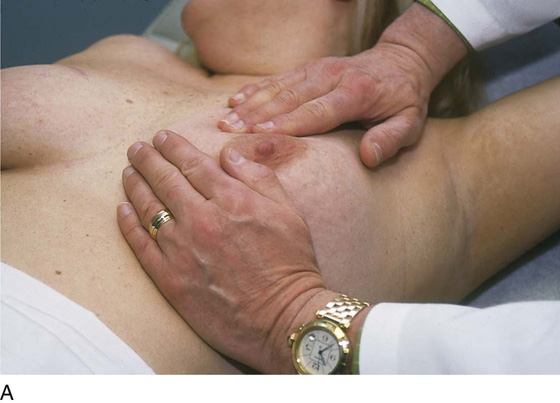

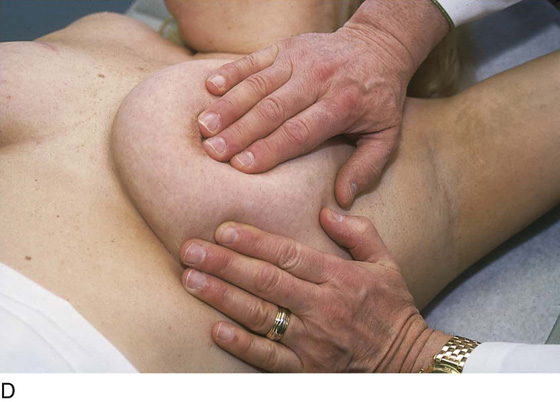

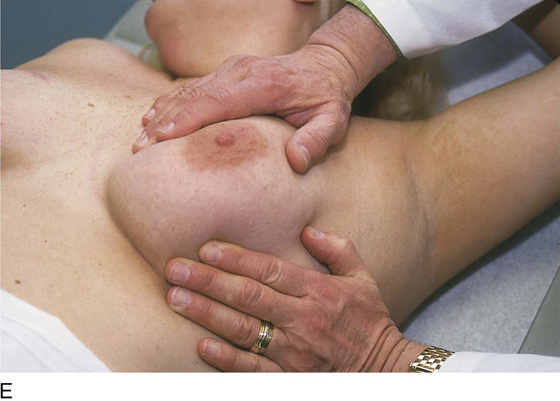

The patient is instructed to lie down on her back (supine position), and the end of the examination table is extended. Utilizing the flat of the hand while supporting the breast with the opposite hand, the examiner palpates the breast against the chest wall. A variety of techniques may be used. A convenient procedure is to divide the breast into three zones from top to bottom, beginning first with the upper third. Palpate beginning below the midaxillary line, and progress medially to the sternum. This is repeated until all three zones have been thoroughly examined. The nipples and areolae are separately examined by palpation and then by compression (Figs. 105–13 and 105–14).

For the sake of completeness, the inframammary ridge is checked separately (Fig. 105–15). The supraclavicular area may be examined in the sitting or supine position (see Fig. 105–11).

Because approximately 5% of breast cancers appear during pregnancy or the postpartum period, it is unwise to delay breast examination during these times. If the woman is lactating, the breasts should be pumped before the examination is performed.

Documentation is exceedingly important. Negatives as well as positives should be written into the patient’s record. Differences in nodularity or lumpiness between the two breasts should be noted. Any mass must be described by size, shape (measured in centimeters), location (precise anatomic), mobility versus fixation, consistency (hard, soft, rubbery), and sensitivity (painful vs. nontender). Nipple discharge should be localized to the compressed quadrant and described as to color and consistency. A guaiac test should be done, and the material placed on a slide, fixed, and sent to pathology.

FIGURE 105–6 The clinical breast exam (CBE) begins with the patient sitting on the end of the examination table facing the examiner.

FIGURE 105–7 The breasts are allowed to relax and hang free by having the patient bring her arms to her sides and lean slightly forward.

FIGURE 105–8 The patient sits erect with her hands on her hips. The breasts are visually examined for symmetry, retraction, nipple location, and appearance. Note the scar in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast.

FIGURE 105–9 The patient is instructed to raise her hands high above her head to place the breast tissue on tension. The skin of the breast is inspected for color changes, edema, thickening, ulceration, or dimpling. The nipples are described as erect, inverted, or distorted.

FIGURE 105–10 The axilla is examined to determine whether there is adenopathy or tenderness. The ipsilateral arm is supported by the examiner to relax the pectoral muscle, while the other hand palpates into the axilla and against the chest wall.

FIGURE 105–11 Next, the supraclavicular area is examined for the presence of lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 105–12 Standing to the side and in back of the patient, the examiner compresses the areola and nipple to determine whether a discharge is present. By milking the individual quadrants, the examiner can determine the relative location from which the discharge is elicited.

FIGURE 105–13 A through E. The patient is placed in the supine position, and the ipsilateral arm is extended above her head. The examiner palpates the breast with his or her flattened fingers against the chest wall. The author prefers to divide the breast into three or four horizontal zones. Palpation begins at the sternum and continues in a lateral direction until the midaxillary line is passed. The exam is repeated for each zone and covers the area from the clavicle above to the lower rib cage below. The nipples and areolar areas are separately compressed.

FIGURE 105–14 The nipple and the areola are squeezed to determine whether any discharge can be identified.

FIGURE 105–15 The inframammary ridge is carefully palpated to finish the examination.

Fine-Needle Aspiration

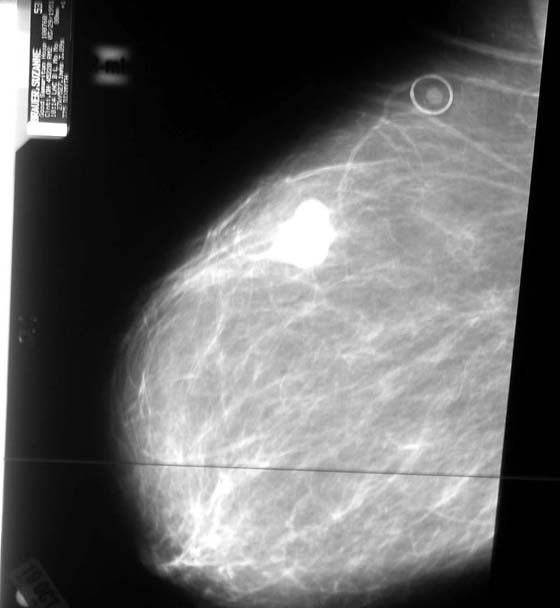

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) coupled with cytology is a diagnostic technique that can be performed safely in the office setting. This may be performed by direct insertion or by ultrasound-guided insertion. A solid mass is unlikely to be differentiated from a breast cyst on the basis of clinical breast exam (CBE) alone. On the other hand, FNA can be used to differentiate between cystic and solid lesions. A diagnostic mammogram is likely to have been ordered before a breast aspiration (Fig. 105–16).

The diagnostic accuracy of FNA can be 95%. This accuracy depends on obtaining a sufficient amount of aspirate and on the proficiency of the cytopathologist. Remember, a negative FNA result should not dissuade one from doing a biopsy.

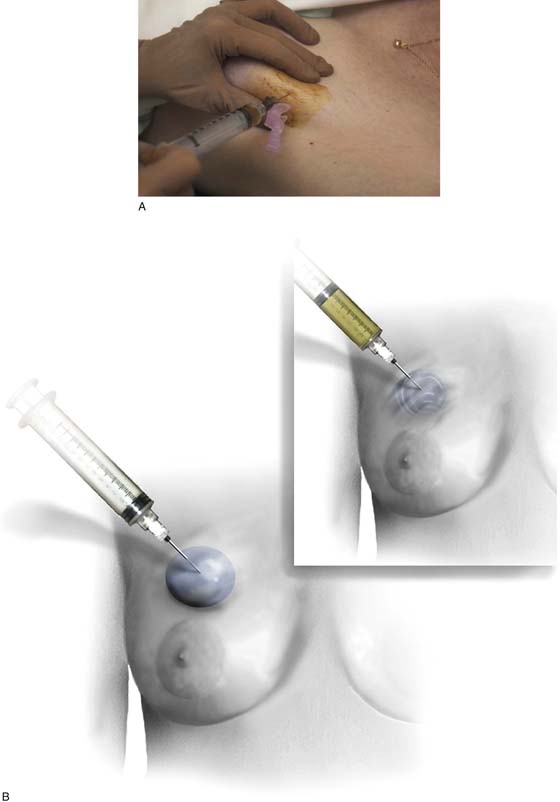

The technique for aspiration is simple. The breast, over the site of the mass, is prepped with an alcohol preparation. The tissue containing the mass is stabilized with one hand. Next, a 10-mL syringe with a 22-gauge needle attached is inserted into the mass while withdrawing on the plunger. If a cyst is present, the contents are aspirated and sent for cytology. Palpation after aspiration (if the lesion is a cyst) should reveal complete collapse and disappearance of the mass. If the mass remains, prompt breast biopsy is indicated (Figs. 105–17 through 105–25).

Specific training is required for gynecologists who wish to perform fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

FIGURE 105–16 This mammogram shows a mass in the upper quadrant, which represents a possible malignant lesion. A biopsy needs to be performed on this mass.

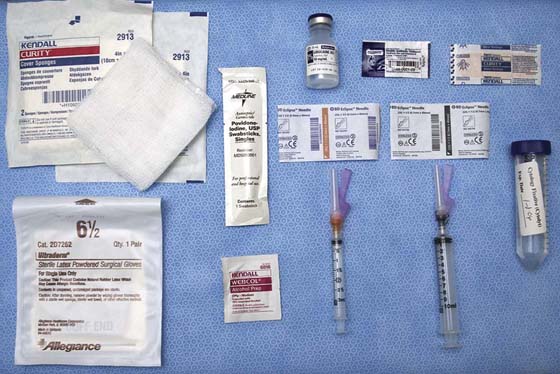

FIGURE 105–17 This photograph illustrates the tools necessary for the performance of fine-needle aspiration. These items include iodine or alcohol skin prep solution, local anesthetic, syringes for anesthesia and aspiration, needles, syringes, cytologic vehicle, antibiotic topical ointment, and adhesive bandages.

FIGURE 105–18 The skin of the breast above the site of the suspected cyst is cleansed with iodine or alcohol. The surgeon must observe sterile technique.

FIGURE 105–19 The location of the breast mass must be stabilized with the fingers of one hand. This position must not be released until the aspiration has been completed.

FIGURE 105–20 The skin overlying the aspiration site is anesthetized by using a 25-gauge needle coupled to a 3- to 5-mL syringe with injection of 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine).

FIGURE 105–21 A. The fine-needle aspiration is performed via a 22-gauge needle and a 10-mL syringe. One cubic centimeter of air may be placed into the syringe before the aspiration. If fluid is obtained, the cyst should be completely emptied. Cytologic examination should be performed if the fluid is bloody (nontraumatic) or cloudy. Additionally, fluid should be sent for cytologic evaluation if the lesion does not disappear. For solid masses, several passes should be made into the lesion at different angles, while the operator firmly holds the lesion in place. During each pass of the needle, suction is maintained on the plunger of the syringe. B. The lesion is aspirated. In this illustration, a “blue dome” cyst is shown. The lesion is cystic, and it will collapse as the fluid is withdrawn (inset).

FIGURE 105–22 The aspirate may be placed into cytology fixative or alternatively spread on a glass slide as a smear. The method for retrieval should be chosen by the surgeon, the gynecologist, and the pathologist.

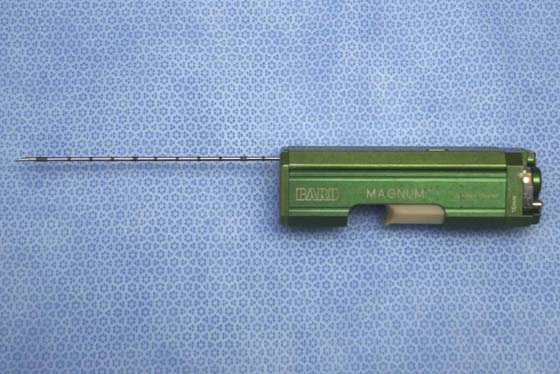

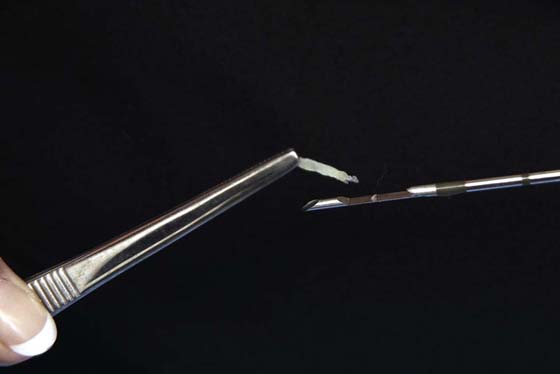

FIGURE 105–23 The core needle is used for sampling solid lesions. The apparatus pictured here is a full-core biopsy instrument.

FIGURE 105–24 The detail of the large-gauge core needle shows its sharp, beveled cutting tip.

FIGURE 105–25 The core needle makes a single pass into the suspected solid tumor. The fragment of retrieved tissue is sent to pathology, where it is embedded and blocked.

Karen S. Columbus

Karen S. Columbus  Michael S. Baggish

Michael S. Baggish