Chapter 13

The Breast1

The shape of the breast is like a gourd. They are round for holding blood to be changed into milk. … They have teats, that the new born child may suck therefrom.

Mondino De’ Luzzi (1275–1326)

General Considerations

In the United States, the National Cancer Institute estimates that one of every eight women (approximately 12.5%) will develop breast cancer during her lifetime. Among the malignant diseases in women, breast cancer is the most common to develop and is the second most common cancer cause of death, after cancer of the lung and bronchus. In 2011, it accounted for 230,480 new cancer cases in American women (30% of all new cancer cases), and 15% of all cancer deaths. There were 39,970 deaths from breast cancer: 39,520 in women, 450 in men. Breast carcinoma in situ, a very early form of the disease, was diagnosed in another 57,650 women.

The incidence of cancer of the breast is higher in the United States than in European or Asian countries. It has been well established that women in underdeveloped nations have lower rates of breast cancer than do women from more affluent societies. Among racial and ethnic groups, white and African-American women have the highest incidence rates of breast cancer (113.2 and 99.3 per 100,000 population, respectively). Asian and Pacific Islander women and Latino women have a lower risk (72.6 and 69.4 per 100,000 population, respectively). The incidence rate for female breast cancer began to decline in 2000. The dramatic decline of almost 7% from 2002 to 2003 has been attributed to reductions in the use of hormone replacement therapy following the publication of results from the Woman’s Health Initiative in 2002 indicating that combined estrogen and progesterone therapy was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and coronary artery disease. Since 2003, breast cancer incidence rates have been stable.

Once breast cancer has occurred in a family, the risk that other women in the same family will have breast cancer is significantly higher. First-degree relatives, such as sisters or daughters, have more than twice the risk for development of breast cancer if the original patient developed cancer in one breast after menopause. Women with a family history of premenopausal breast cancer in one breast have three times the risk. If the original patient had postmenopausal cancer in both breasts, the first-degree relatives have more than four times the risk. First-degree relatives of patients with cancer in both breasts before menopause have nearly nine times the risk.

Most breast cancers are detected as painless masses, noticed by either the patient or the examiner during a routine physical examination. The earlier the diagnosis is made, the better the prognosis is. Screening for breast cancer is best accomplished by a thorough clinical breast examination, breast self-examination (BSE), and mammography. Mammography is the most sensitive method for the detection of breast cancer and has been demonstrated to reduce the breast cancer mortality rate.

Structure and Physiology

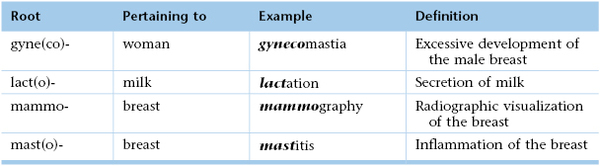

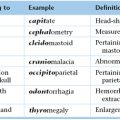

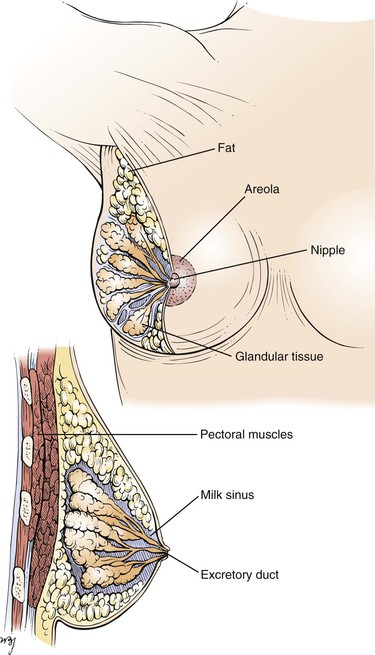

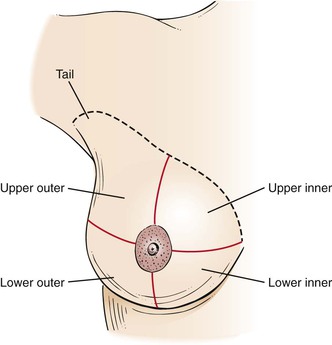

The mammary glands are the distinguishing feature of all mammals. Human breasts are conical in form and are often unequal in size. The breast extends from the level of the second or third rib to the level of the sixth or seventh rib, from the sternal edge to the anterior axillary line. The “tail” of the breast extends into the axilla and tends to be thicker than the other breast areas. This upper outer quadrant contains the greatest bulk of mammary tissue and is frequently the site of neoplasia. Figure 13-1 illustrates the normal breast.

Figure 13–1 Anatomy of a normal breast.

Both the nipple and areola contain smooth muscle that serves to contract the areola and compress the nipple. Contraction of the smooth muscle makes the nipple erect and firm, thereby facilitating the emptying of the milk sinuses.

The skin of the nipple is deeply pigmented and hairless. The dermal papillae contain many sebaceous glands, which are grouped near the openings of the milk sinuses. The skin of the areola is also deeply pigmented but, unlike the skin of the nipple, contains occasional hair follicles. Its sebaceous glands are commonly seen as small nodules on the areolar surface and are termed Montgomery‘s tubercles.

Cooper‘s ligaments are projections of the breast tissue that fuse with the outer layers of the superficial fascia and serve as suspensory structures.

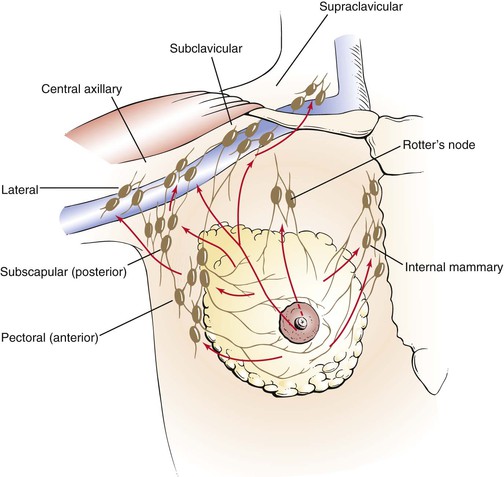

The blood supply to the breast is carried by the internal mammary artery. The breast has an extensive network of venous and lymphatic drainage. Most of the lymphatic drainage empties into the nodes in the axilla. Other nodes lie beneath the lateral margin of the pectoralis major muscle, along the medial side of the axilla, and in the subclavicular region. The main lymph node chains and lymphatic drainage of the breast are illustrated in Figure 13-2.

Figure 13–2 Lymphatic drainage of the breast.

Several physiologic changes occur in the breast. These changes are a result of the following factors:

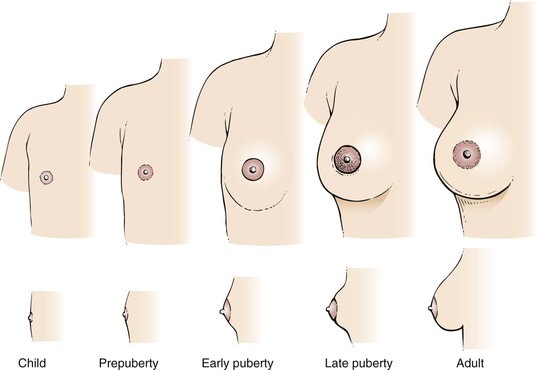

At birth, the breasts contain a branching system of ducts emptying into a developed nipple. There is elevation of only the nipple at this stage. Shortly after birth, there is a slight secretion of milky material. After 5 to 7 days, this secretory activity stops. Before puberty, there is elevation of the breast and nipple, called the breast bud stage. The areola has increased in size. At the onset of puberty, the areola enlarges further and darkens. A distinct mass of glandular tissue begins to develop beneath the areola. By the onset of menstruation, the breasts are well developed, and there is forward projection of the areola and nipple at the apex of the breast. When the breast has reached maturity 1 to 2 years later, only the nipple projects forward; the areola has receded to the general contour of the breast. The stages of breast development from birth to adulthood are illustrated in Figure 13-3. Figure 21-47 further illustrates and describes the breast developmental stages.

Figure 13–3 Stages of breast development.

The nodularity, density, and fullness of the adult breast depend on several factors. Most important is the presence of excess adipose tissue. Because the mammary gland consists mainly of adipose tissue, women who are overweight have larger breasts. Pregnancy and nursing also alter the character of the breasts. Often, women who have nursed have softer, less nodular breasts. However, because the glandular tissue is approximately equal in all women, the size of the breast is unrelated to nursing. With menopause, the breasts decrease in size and become less dense. There is an associated decrease in elastic tissue as women age.

The major physiologic change related to the menstrual cycle is engorgement, occurring 3 to 5 days before menstruation. This is an increase in the size, density, and nodularity of the breasts. There is also an increased sensitivity of the breasts at this time. Because the nodularity of the breasts increases, the examiner should not attempt to diagnose a breast mass at this time. The patient should be reevaluated during the midperiod of the next cycle.

With pregnancy, the breasts become fuller and firmer. The areolae darken, and the nipples become erect as they enlarge. As the woman approaches the third trimester, a thin, yellowish secretion, called colostrum, may be noted. After the birth of the child, if the mother begins nursing within 24 hours, the secretion of colostrum stops, and the secretion of milk begins. During nursing, the breasts become markedly engorged. After the woman has stopped nursing, lactation continues for a short time.

The neuroendocrine control of the breasts can be outlined as follows. Suckling produces nerve impulses that travel to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete prolactin, which acts on the glandular tissue of the breast to produce milk. The hypothalamus also stimulates the posterior pituitary to produce oxytocin, which stimulates the muscle cells surrounding the glandular tissue to contract and force the milk into the ductular system.

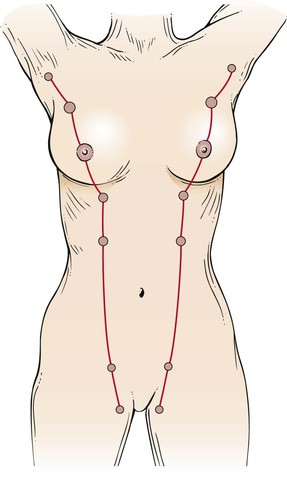

Many abnormalities of the breast are related to its embryologic characteristics. An epithelial ridge, called the milk line, forms along each side of the body from the axilla to the inguinal region. Along this milk line are multiple rudiments for future breast development. In humans, only one rudimentary pair in the pectoral region persists and eventually develops into normal breasts. Accessory breasts or nipples are present in as many as 2% of white women. Accessory breasts may exist as glandular tissue, nipple, or only the areola. The axilla is the most common site for these anomalous structures, followed by a site just below the normal breast. In more than 50% of all patients with accessory breast tissue, the anomalies are bilateral. In general, accessory breast tissue is of little clinical significance. It usually has no physiologic function and is rarely associated with disease. Figure 13-4 illustrates the milk line. Figure 13-5 shows an accessory nipple.

Figure 13–4 The milk line.

Figure 13–5 Accessory nipple.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most important symptoms of breast disease are the following:

Mass or Swelling

During self-examination, a patient may discover a breast mass. Ask the following questions:

“When did you first notice the lump?”

“Have you noticed that the mass changes in size during your menstrual periods?”

“Have you ever noticed a mass in your breast before?”

“Have you noticed any skin changes on the breast?”

“Have you had any recent injury to the breast?”

“Is there any nipple discharge? Nipple retraction?”

“Do you have breast implants?” If yes, “What are they made of?”

If the lump enlarges during the premenstrual and menstrual stages of the cycle, it is likely that the woman is detecting only physiologic nodularity. The association of nipple discharge, nipple inversion, or skin changes overlying the mass is strongly suggestive of neoplasm. Figure 13-6 shows a large breast mass found on self-examination.

Figure 13–6 Large breast mass found on self-examination.

Pain

Breast pain or tenderness is a common symptom. Most often, these symptoms are attributable to the normal physiologic cycle. Ask the following questions of any patient with breast pain:

“When did you first experience the pain?”

“Are there any changes in the pain with your menstrual cycle?”

“Do you have pain in both breasts?”

“Have you had any injury to the breast?”

“Is the pain associated with a mass in the breast? Nipple discharge? Nipple retraction?”

Rapidly enlarging cysts may be painful. Cystic disease of the breasts is usually painless. Although breast pain is a relatively uncommon manifestation of breast cancer, its presence does not exclude the diagnosis. Never delay evaluation of a painful breast mass.

Nipple Discharge

Nipple discharge is not a common symptom, but it should always raise the suspicion of breast disease, especially if the discharge occurs spontaneously. Any patient who describes a nipple discharge should be asked the following questions:

“What is the color of the discharge?”

“Do you have a discharge from both breasts?”

“When did you first notice the discharge?”

“Is the discharge related to your menstrual cycle?”

“When was your last menstrual cycle?”

“Is the discharge associated with nipple retraction? A breast mass? Breast tenderness?”

If the woman has recently delivered a child, ask

The most common types of discharge are serous and bloody. A serous discharge is thin and watery and may appear as a yellowish stain on the patient’s garments. This commonly results from an intraductal papilloma in one of the large subareolar ducts. Women taking oral contraceptives may complain of bilateral serous discharge. A serous discharge can also occur in women with breast carcinoma.

A bloody discharge is associated with an intraductal papilloma, which is common among pregnant and menstruating women. It may, however, be associated with a malignant intraductal papillary carcinoma. The presence of any nipple discharge is more important than its character because both types of discharge are associated with benign or malignant disease.

A milky discharge is usually milk. The secretion of milk while not nursing is known as galactorrhea. It is common for women to continue to secrete milk for a few months after they stop nursing. In rare instances, the secretion may continue for a year. Abnormal lactation may also result from a pituitary tumor that interferes with the normal hypothalamic-pituitary feedback loop or from the use of certain tranquilizing medications. Mechanical stimulation or suckling may produce physiologic stimulation.

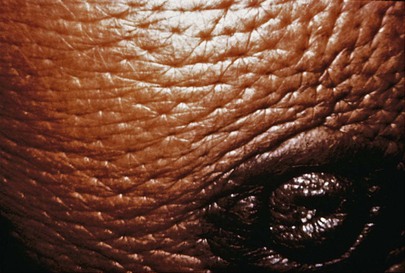

Change in Skin over Breast

A change in the color or texture of the skin of the breast or areola is an important symptom of breast carcinoma. The presence of dimpling, puckering, or scaliness warrants further investigation. The presence of unusually prominent pores, indicative of edema of the skin, is an important sign of malignancy. This clinical sign is called peau d’orange because of its orange-peel appearance. During the early stages of breast carcinoma, the lymphatic vessels of the breast are dilated and contain occasional emboli of carcinoma cells. Limited peau d’orange over the lower half of the areola is present. As the disease progresses, more lymphatic vessels become filled with carcinoma cells that block them, creating more generalized edema. The classic appearance of peau d’orange is pictured in Figure 13-7.

Figure 13–7 Peau d’orange.

General Suggestions

The interviewer should pay special attention to the family history of any woman presenting with symptoms of breast disease. As indicated earlier, breast cancer may be a familial disorder. The occurrence of breast disease in a close relative and the age at which it developed are relevant to the patient’s disease. Ask the patient the following questions:

“Have you had a mammogram?” If yes, “When and what was the result?”

“Have you had breast cancer without the removal of your breast?”

“Do you have breast implants?”

“Have you had any breast biopsies or breast surgery?”

“Have you ever had radiation treatments to your breasts?”

Impact of Breast Disease on the Woman

The psychosocial problems resulting from breast cancer are far-reaching. Although the loss of an extremity is more disabling in everyday life, the loss of a breast may produce intense feelings of loss of the feminine identity. Many women who lose a breast become depressed because they feel their symbol of femininity has been removed. They are afraid that they will no longer be considered “whole” women because their bodies have been maimed. They fear that they can no longer be loved normally and that they can no longer experience sexual satisfaction. They fear looking at themselves in a mirror and perceive themselves as ugly. The asymmetry is often described as “mutilation” or “a bomb crater.” After mastectomy, women often suffer from sexual inhibition and sexual frustration.

Once a woman has discovered a mass in her breast, she may become intensely fearful. The fear of breast cancer is twofold: It is a cancer, sometimes with a bad prognosis, and it often is associated with disfigurement. For these reasons, the patient may deny the presence of the mass and delay seeking medical attention. This is most unfortunate as treatment of many breast cancers in the early stages can be curative.

After a mastectomy, the patient may suffer from depression and low self-esteem. The patient should be supported, and counseled if necessary. Open communication and sharing of feelings among the patient, husband, significant other, physician, and family are important factors in the psychologic rehabilitation of the woman.

The patient pictured in Figure 13-8 had inflammatory carcinoma of her left breast, with massive lymphedema of the left arm. The patient had noticed that her arm had been swelling for the past few months, and she now needed support to raise it. She presented to the clinic complaining only about the heaviness of her arm. When examination revealed the breast lesion, she stated that she had noticed the breast changes “only a few days ago.” This is another example of denial of illness (see also the patient shown in Fig. 2-1).

Figure 13–8 Inflammatory breast carcinoma.

During the past 30 years, advances in surgery and radiation treatment have produced alternatives to mastectomy. Breast conservation and reconstruction of the breast after mastectomy have become well-established treatment options available to many patients. Lumpectomy with radiation for small, early cancers results in similar survival rates as mastectomy. The decisions regarding treatment options of breast cancer are complex and personal. It is imperative that the woman and her physician explore all options with respect and understanding because rushing into an ill-informed choice that may result in regret in the future.

Physical Examination

No special equipment is necessary for the examination of the breast. The examination of the breast consists of the following:

The examination of the breast is in two parts. The first is performed with the patient sitting up. Inspection of the breasts and palpation of the lymph nodes are done in this position. The second is performed with the patient lying down. The examiner systematically palpates the entire breast by using firm, gentle pressure exerted by the pulp of his or her finger rather than the fingertips.

To facilitate communication, the breast is pictorially divided into four quadrants. Two imaginary lines run through the nipple at right angles to each other. By visualizing the breast as a face of a clock, one line is the “12 o’clock–6 o’clock” line, and the other is the “3 o’clock–9 o’clock” line. The resulting four quadrants are the upper outer, upper inner, lower outer, and lower inner. The “tail” is an extension of the upper outer quadrant. These regions are illustrated in Figure 13-9.

Figure 13–9 The four breast quadrants.

Inspection

The woman should be seated on the edge of the examination table, facing the examiner. The examiner should ask the woman to remove her gown to her waist.

Inspect the Breasts

Inspection is first accomplished with the patient’s arms at her side, as shown in Figure 13-10. Tell the patient, “I am inspecting the breasts for any changes in the skin, contour, or symmetry.” The breasts are inspected for size, shape, symmetry, contour, color, and edema. The nipples are inspected as to size, shape, inversion, eversion, or discharge. The nipples should be symmetric. Is any abnormal bulging present?

Figure 13–10 Position of patient for inspection of the breasts.

The skin of the breast is observed for edema. Edema of the skin of the breast that overlies a malignancy may manifest as peau d’orange.

Is erythema present? Erythema is associated with infection and with inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. Figure 13-11 shows marked erythema of the breast secondary to inflammatory breast carcinoma. The scar above the areola is from a previous biopsy of a benign breast mass.

Figure 13–11 Erythema of the breast.

Is dimpling present? The examiner must inspect the breasts for the presence of retraction phenomena. Dimpling is a sign of retraction phenomena that are caused by an underlying neoplasm and its fibrotic response. Skin retraction is commonly associated with malignancy that causes an abnormal traction on Cooper’s ligaments. The shortening of the larger mammary ducts by cancer produces flattening or inversion of the nipple. A change in the position of the nipple is important because many women have a congenitally inverted nipple on one or both sides. The dimpling of the breast in Figure 13-12 is associated with a bloody nipple discharge; both are secondary to carcinoma.

Is there a red, scaling, crusting plaque around one nipple, areola, or surrounding skin? Paget‘s disease of the breast is a surface manifestation invariably associated with an underlying invasive or intraductal carcinoma. The lesion appears eczematous, but unlike eczema, it is unilateral. The skin may also weep and be eroded. A much less common form is extramammary Paget’s disease, which is seen around the anus or genitalia and is usually associated with malignant disease of the adnexa, bowel, or genitourinary tract. Figure 13-13 shows Paget’s disease of the breast; an underlying ductal adenocarcinoma was present.

Figure 13–13 Paget’s disease of the breast.

Inspect the Breasts in Various Postures

Inspection is next performed while the woman assumes several postures that may bring out signs of retraction that were less evident previously. Ask the woman to press her arms against her hips. This maneuver tenses the pectoralis muscles, which may bring out dimpling caused by fixation of the breast to the underlying muscles. This technique is shown in Figure 13-14. If a malignancy is present, the abnormal attachment of the tumor to the fascia and pectoralis muscle pulls on the skin and may produce skin dimpling. Any bulging may also indicate an underlying mass.

Figure 13–14 Technique for tensing the pectoralis muscles.

Another maneuver, which is useful for a woman with pendulous breasts, involves her bending at the waist and allowing her breasts to hang free from the chest wall. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 13-15. A carcinoma causing fibrosis in one breast produces a change in the contour of that breast.

Figure 13–15 Position of patient for inspecting the breasts.

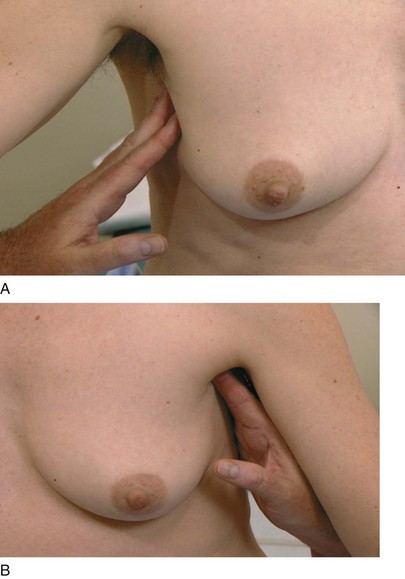

Axillary Examination

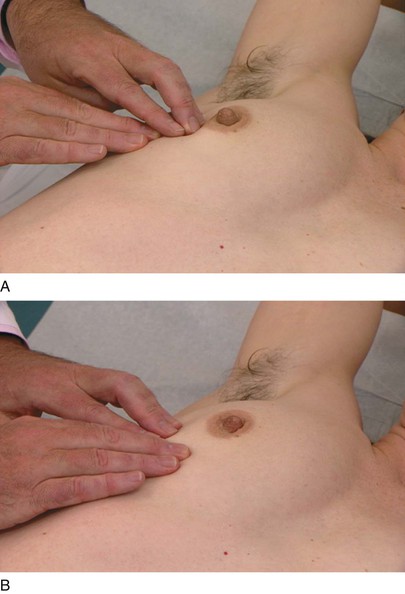

The axillary examination is performed with the patient seated facing the examiner. Examination of the axilla is best accomplished by relaxing the pectoral muscles. To examine the right axilla, the patient’s right forearm is supported by the examiner’s right hand. The tips of the fingers of the examiner’s left hand start low in the axilla, and, as the patient’s right arm is drawn medially, the examiner advances the left hand higher into the axilla. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 13-16. The supraclavicular, subclavian, and axillary regions are palpated.

Figure 13–16 Technique for axillary examination. A, Low axilla (right side). B, High axilla (left side).

The technique of using small, circular motions of the fingers riding over the ribs is used for detecting adenopathy. Freely mobile nodes 3 to 5 mm in diameter are common and are usually indicative of lymphadenitis secondary to minor trauma of the hand and arm. After one axilla is examined, the other is evaluated by the examiner’s opposite hand.

Palpation

The woman is asked to lie down and is told that the breast will next be palpated. The examiner stands at the right side of the patient’s bed. Although the examiner can usually palpate each breast from the patient’s right side, it is often better with large-breasted women to examine the left breast from the left side.

The breast is best palpated by allowing it to lie evenly distributed over the chest wall. Small-breasted women may lie with their arms at their sides; larger breasted women should be instructed to place their hands behind their head. A pillow placed beneath the shoulder on the side being examined facilitates the examination.

Palpate the Breast

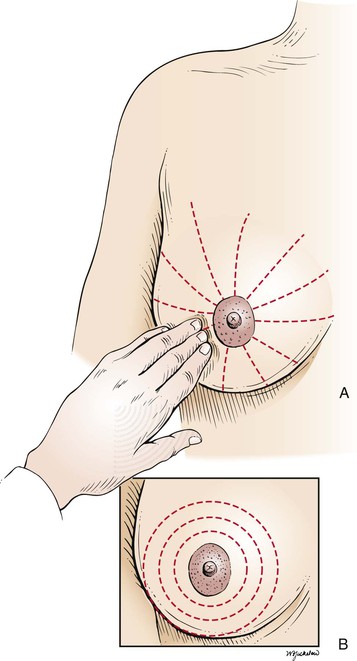

In palpation of the breast, the examiner should use both the flat of the hand and the fingertips, as demonstrated in Figure 13-17. Palpation should be performed by the “spokes of a wheel,” the concentric circle, or the vertical strip method. The “spokes of a wheel” method starts at the nipple (see Fig. 13-17A). The examiner should start the palpation by moving outward from the nipple to the 12 o’clock position. The examiner then should return to the nipple and move along the 1 o’clock position and continue the palpation around the breasts. The concentric circles approach (see Fig. 13-17B) also starts at the nipple, but the examiner moves from the nipple in a continuous circular manner around the breast. Any lesion found by either technique is described as being a certain distance from the nipple in clock time: for example, “3 cm from the nipple along the 1 o’clock line.” These techniques are illustrated in Figure 13-18.

Another method is the vertical strip, or grid, technique. The breast is divided into eight or nine vertical strips, each approximately one finger’s width. The examiner’s three middle fingers are held together and slightly bowed to ensure contact with the skin. The pads, not the tips, of the fingers must be used for palpation. Using dime-sized circles, the examiner evaluates the breast at each of three different levels of pressure: light, medium, and deep. Each strip consists of 9 or 10 areas of palpation, slightly overlapping the previous area, and each vertical strip is evaluated with the three pressures. Although this method has been shown to be superior to the other traditional types of breast palpation, it is more time consuming and may be best used by women for BSE.

The examiner should be careful when evaluating the inframammary fold. This fold is commonly observed in older women and is the area where the mammary tissue is bound tightly to the chest wall. Often, this ridge is mistaken for a breast disorder.

Describe the Findings

If a mass is palpated, the following characteristics should be described:

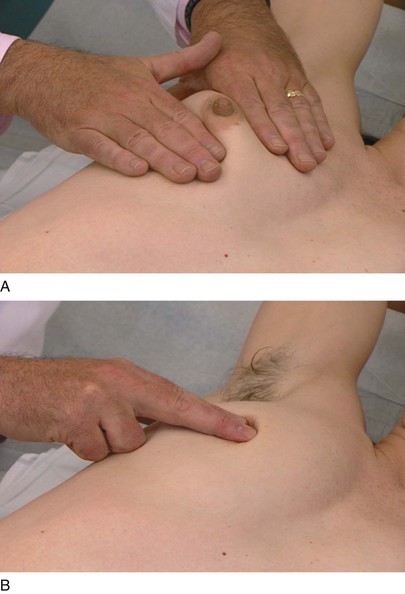

Evaluate for Retraction Phenomenon

If a mass is detected, molding of the skin may be useful to determine whether the retraction phenomenon is present. The examiner should elevate the breast around the mass. Dimpling may occur if a carcinoma is present. Figure 13-19 demonstrates the technique of molding and its result in a patient with carcinoma of the breast. Notice the marked dimpling of the breast. This patient also had metastatic lesions of breast carcinoma on her arm, together with lymphedema. She presented to the clinic stating that she had discovered the swollen arm the day before.

Palpate the Subareolar Area

The subareolar area, the area directly under the areola, should be palpated while the patient is lying supine. In the subareolar area, the breast tissue is less dense. An abscess of Montgomery’s glands in the areola may cause a tender mass in this area.

Examine the Nipple

Examination of the nipple concludes the examination of the breast. Inspect for nipple retraction, fissures, and scaling. To examine for discharge, place each hand on either side of the nipple and gently compress the nipple, noting the character of any discharge. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 13-20. Ask the woman whether she would prefer to perform this part of the examination herself.

Examination of the Male Breast

Examination of the breast should be performed on all men. The nipples should be inspected for swelling, discharge, and ulceration. The areola and the subareolar tissue should be palpated for any masses. The axillary examination is as indicated for women.

Breast Self-Examination2

Although monthly BSE was recommended for many years, it has been recognized that BSE has limited value in detecting early cancer. Organizations such as the American Cancer Society, American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the U.S. Preventative Service Task Force have found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against BSE. The emphasis on monthly BSE has been replaced by the concept of “breast self-awareness” whereby women older than 20 years become knowledgeable about the normal appearance and feel of their breasts, but without a specific schedule or examination technique. A physician should help educate the woman so that she can have the awareness to report any skin changes, dimpling, nipple discharge or presence of new lumps or bumps. Although medical attention should be sought for any of these findings, she can be reassured that most findings are not cancer.

Many women will want to know how best to examine their breasts. The techniques of BSE are included here for the purpose of patient education:

The Male Breast

Gynecomastia is the enlargement of one or both breasts in a man. It often occurs at puberty, occurs with aging, or is drug related. Figure 13-21 shows a 90-year-old man who was treated with diethylstilbestrol for carcinoma of the prostate and developed gynecomastia.

Figure 13–21 Gynecomastia.

Carcinoma of the breast affects approximately 1000 men per year in the United States. More than 300 men per year die of metastatic breast cancer. The average age at the time of diagnosis is 59 years. The most common clinical manifestation, occurring in 75% of cases, is a painless, firm, subareolar mass or a mass in the upper outer quadrant of the breast.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Cancer of the Breast

There is mounting evidence that defects in DNA repair may be significant factors for the development of breast cancer. Two genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, have been identified as tumor suppressor genes or breast cancer susceptibility genes and appear to be involved with gene repair. Tumor suppressor genes keep cellular growth in control but can cause cancer when their function is blocked. More than 2000 mutations have been described for these tumor suppressor genes. When mutations or deletions occur in these suppressor genes, the incidence of neoplastic transformation is much greater. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with proteins, such as p53 and RAD51, which are involved with DNA repair and transcriptional activation. Carriers of germline mutations in BRCA1, located on chromosome 17, or BRCA2, located on chromosome 13, have an increased incidence of early-onset, familial breast, or ovarian cancer. Mutant BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes account for 50% of hereditable breast cancers.

Mutations in these tumor suppressor genes have been found in only 5% to 10% of women with early-onset breast cancers. If a mutation in the BRCA1 gene is present in a woman, however, it is estimated that her lifetime risk for development of breast cancer is approximately 60% to 80%, and she has a 33% chance for development of ovarian cancer. A man with a mutant allele of the gene has an increased incidence of prostate cancer. BRCA2 is associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer in men and women. Some population groups, such as individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, have an increased prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Researchers have discovered that 2.5% of these women may carry the mutation—an occurrence that is approximately five times greater than that of the general population. Although these mutations account for less than 10% of all breast cancer cases, they are very rare in the general population (less than 1%) so widespread genetic testing is not recommended.

The finding of a breast mass on palpation, even in the presence of a normal mammogram, necessitates a biopsy. However, breast palpation has a much lower true-positive rate (sensitivity) than mammography. There are many false-negative findings in breast palpation. This error is related to the difficulty in palpating a small mass in large breasts, the inherent properties of breast tissue, and poor technique. The limitations of physical examination and mammography are shown in Table 13-1.

Table 13–1

Limitations of Physical Examination and Mammography

| Operating Characteristic | Physical Examination | Mammography |

| Sensitivity (%) | 24 | 62 |

| Specificity (%) | 95 | 90 |

Data from Bond WH: The treatment of carcinoma of the breast. In Jarrett AS, editor: Proceedings of a symposium on the treatment of carcinoma of the breast, Amsterdam, 1968, Excerpta Medica.

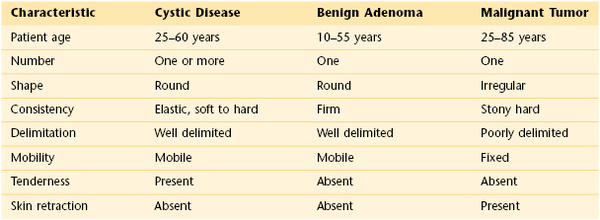

The physical examination is of great importance in determining the probability that a mass is cancerous. Any lump detected by either the patient or the examiner carries a 20% risk of cancer. As indicated in Table 13-2, benign lesions usually are freely mobile, have well-delimited borders, and feel soft or cystic. However, of all breast cancers, 60% are freely mobile, 40% have well-delimited borders, and 50% feel soft or cystic. A fixed lesion has a 50% chance of being malignant. If this lesion has irregular borders, the likelihood of being malignant rises to 60%. The sensitivity and specificity of certain physical findings in evaluating a breast mass for malignancy are shown in Table 13-3.

Table 13–3

Characteristics of Breast Masses Suspect for Cancer

| Characteristic | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity* (%) |

| Fixed mass | 40 | 90 |

| Poorly delimited mass | 60 | 90 |

| Hard mass | 62 | 90 |

* Based on the assumption that nonmalignant breast masses have benign characteristics.

Data from Venet L, Strax P, Venet W, et al: Adequacies and inadequacies of breast examination by physicians in mass screening, Cancer 28:1546, 1971.

Screening Guidelines for Early Detection of Cancer of the Breast

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society recommendations for early breast cancer detection in women without breast symptoms. [Available at] http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs-bse [Accessed January 30, 2013] .

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer: early detection. Patient instruction for breast self examination. [Available at] http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs-bse [Accessed January 30, 2013] .

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2011.

Bickell NA, Aufses AH, Chassin MR. The quality of early-stage breast cancer care. Ann Surg. 2000;232:220.

Collins FS. BRCA1: lots of mutations, lots of dilemmas. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:186.

Couch FJ, et al. BRCA1 mutations in women attending clinics that evaluate the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1409.

Domchek SM, Antoniou A. Cancer risk models: translating family history into clinical management. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:515.

Easton DF, et al. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:265.

Fletcher SW, et al. How best to teach women breast self-examination: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:772.

Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:326.

Ghafoor A, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:342.

Gómez-Raposo C, et al. Male breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:451.

Harlan LC, et al. Breast cancer in men in the United States: a population-based study of diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2010;116:3558.

Hicks MJ, et al. Sensitivity of mammography and physical examination of the breast for detecting breast cancer. JAMA. 1979;242:2080.

Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:1010.

Krainer M, et al. Differential contributions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to early-onset breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1416.

Malumbres M, Baracid M. Timeline: RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459.

National Cancer Institute. Breast cancer prevention. Health professional version. Overview and description of evidence. [Updated October 5, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/breast/healthprofessional/allpages/print [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

National Cancer Institute. Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Health professional version. [Updated December 21, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Nattinger A. In the clinic: breast cancer screening and prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:ITC4-1.

Parmigiani G, et al. Validity of models for predicting BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:441.

Rebbeck TR, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616.

Smith IE, Dowsett M. Aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2431.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:41.

Smith RA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:141.

Struewing JP, et al. The risk of developing cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1401.

Thomas DB, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: methodology and preliminary results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:355.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations (clinical guidelines). Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:355.

Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108:171.

1 The author thanks Ellen Landsberger, MD, Associate Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, who reviewed the chapter for this edition.

2 The importance of breast self-examination has been recognized for more than 60 years. However, to date, the efficacy of this examination is not definitive. A large, randomized, controlled trial was conducted in 1997 by Thomas and associates in Shanghai and included more than 267,040 women, half of whom were given intensive training in breast self-examination; the other half of whom were asked to attend training sessions on the prevention of low back pain. All women were observed for 5 years for the development of breast diseases. The study showed neither a significant difference in mortality rate in the two groups nor an earlier identification of breast disease in the group trained in breast self-examination. The authors’ conclusion was that “there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the teaching of breast self-examination.”