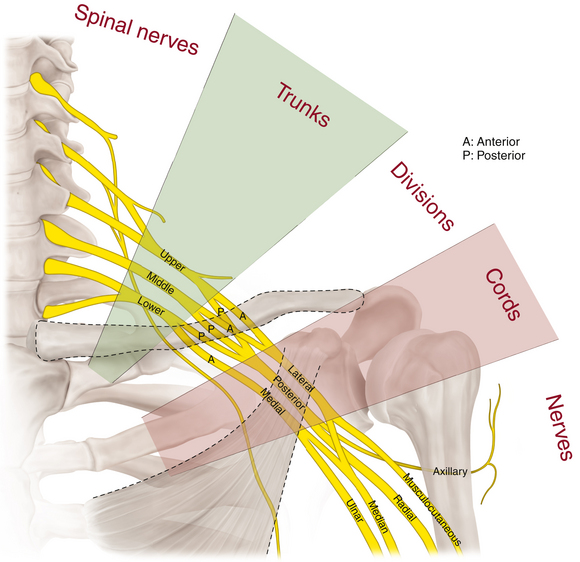

Chapter 2 The Brachial Plexus

Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus

Anatomy

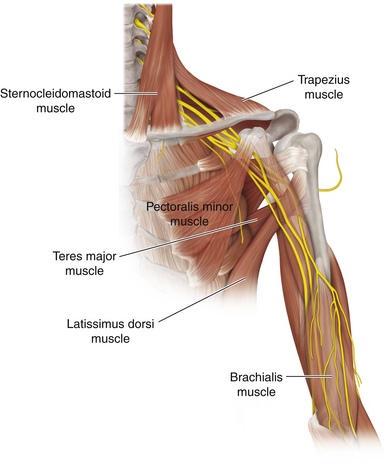

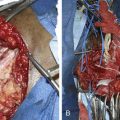

• The surgeon must review the appropriate osteology. No matter how dense the scarring, the bony points are palpable at surgery and form welcome guides (Figures 2-1 and 2-2).

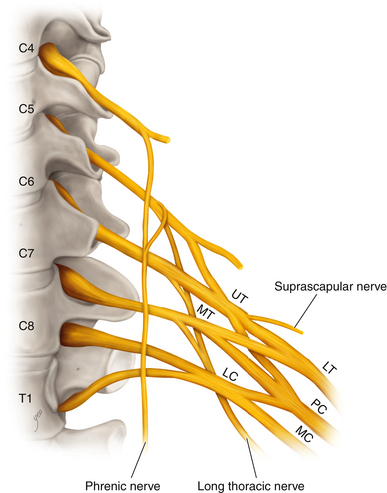

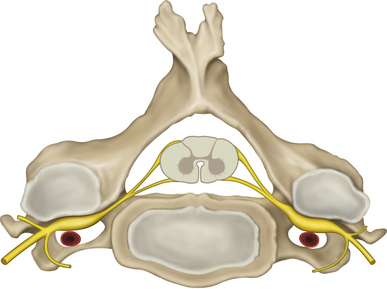

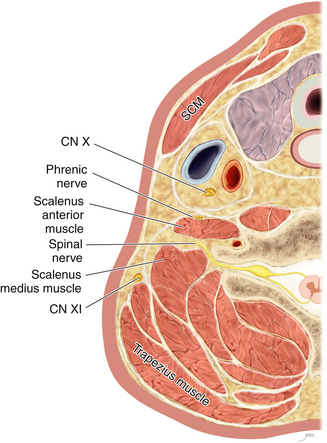

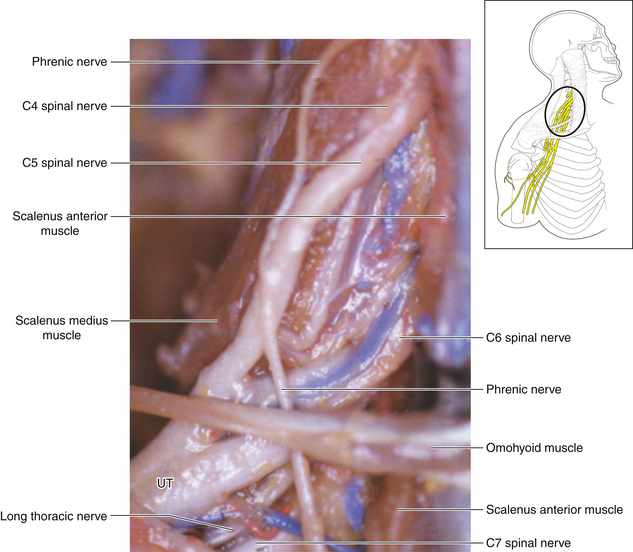

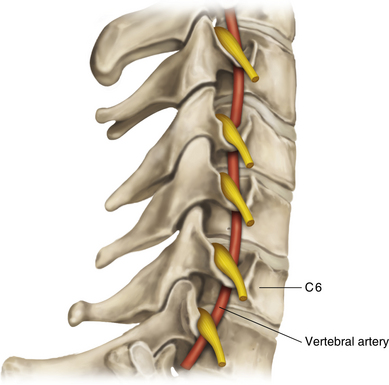

• The transverse processes of the lower cervical vertebrae should be studied in detail so that the surgeon understands the relationship of the intervertebral foramen to the transverse process, which forms a gutter supporting the spinal nerves, and the relationship of both to the vertebral artery, vein, and accompanying sympathetic fibers (Figures 2-3 and 2-4).

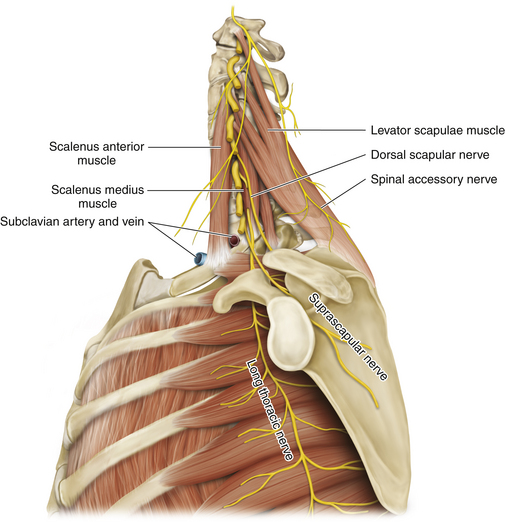

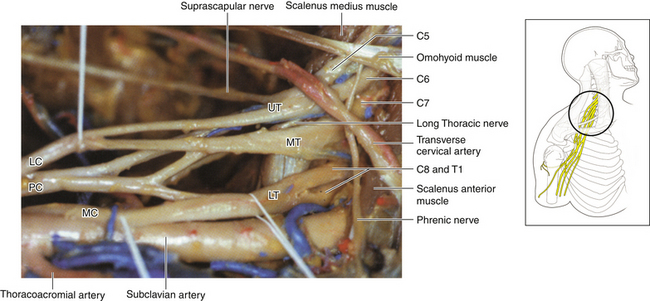

• The scalenus anterior is attached to the anterior tubercle and the scalenus medius to the posterior tubercle of the transverse process (Figure 2-5).

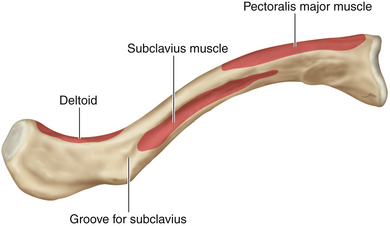

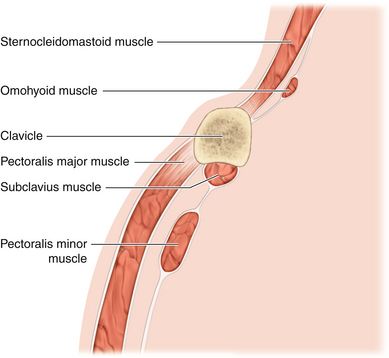

• The clavicle should be examined so that surgeon understands the points of attachment of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), pectoralis major, deltoid, and subclavius (Figures 2-6 and 2-7). On rare occasions, the clavicle is divided at surgery, using a Gigli saw (Figure 2-8).

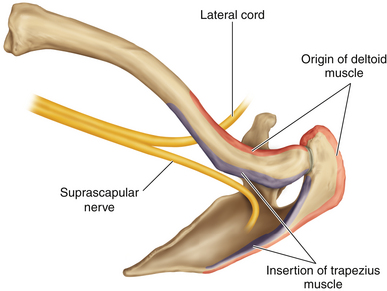

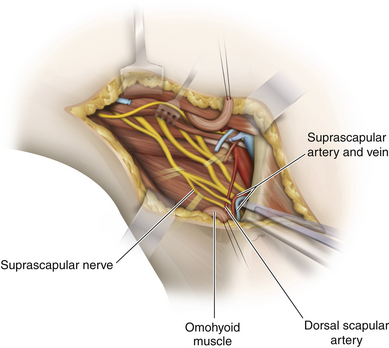

• The scapula should be reviewed so that the transverse scapular ligament can be located. This ligament is the point of attachment of the inferior belly of the omohyoid; the suprascapular nerve courses below it (Figure 2-9).

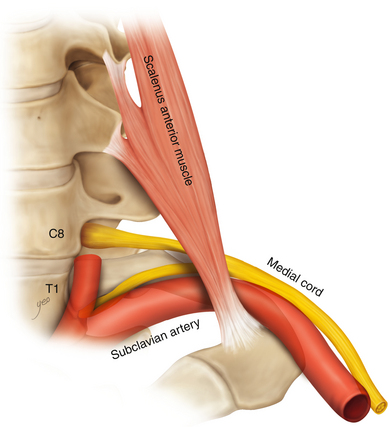

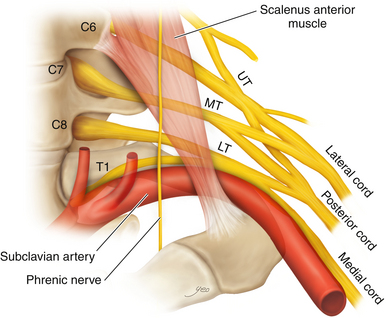

• The first rib should be mastered. The upper border is characteristically sharp. The stellate ganglion is anterior to the neck, and the vertebral artery ascends to the transverse process of C6, anterior to the ganglion. The point of attachment of the scalenus anterior should be clearly understood, because this separates the vein in front from the artery and lower trunk behind.

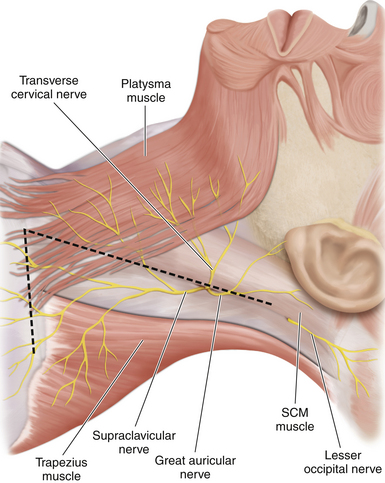

• The investing fascia of the neck splits to enclose the SCM, covers the posterior triangle, and splits to enclose the trapezius (Figure 2-10).

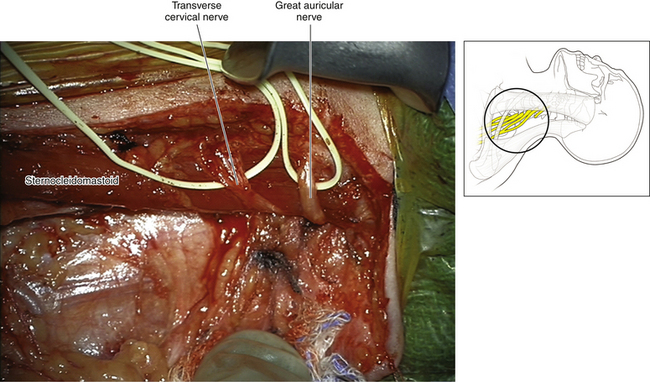

• The accessory nerve supplies the SCM and trapezius. Winding around the posterior border of the SCM are cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus. The transverse cervical and greater auricular nerves are excellent landmarks to both CN XI and C5 (Figures 2-11 and 2-12).

• There is a small triangular gap between the clavicular attachment of the SCM and the manubrial attachment. Immediately posterior to this interval is the termination of the internal jugular vein (Figure 2-13).

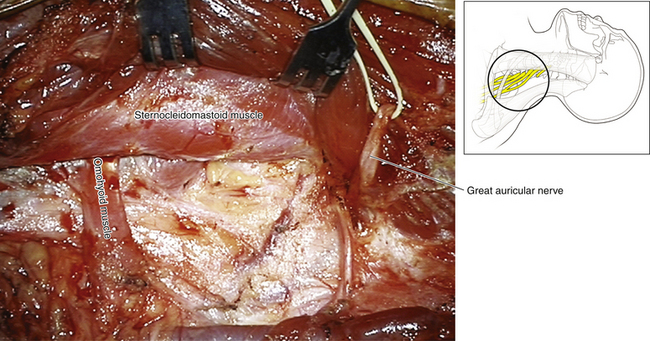

• The omohyoid consists of two bellies joined by an intermediate tendon. The tendon overlies the jugular vein, and the inferior belly runs parallel to the suprascapular nerve to the suprascapular notch (Figure 2-14).

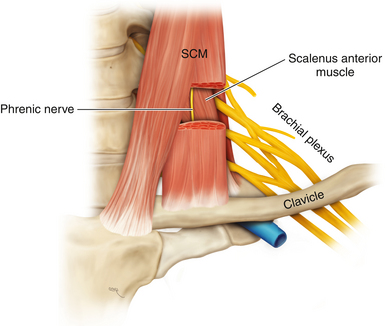

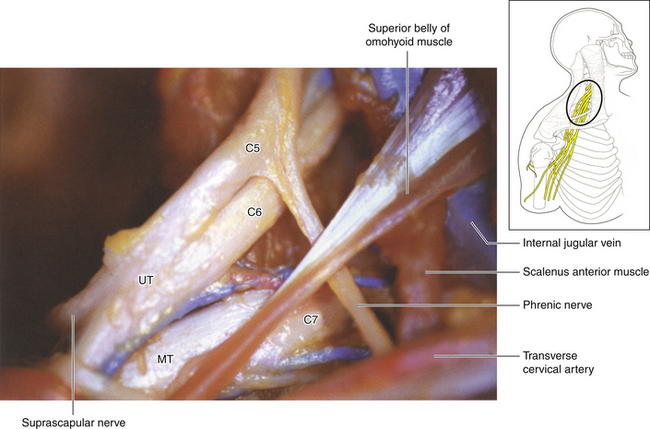

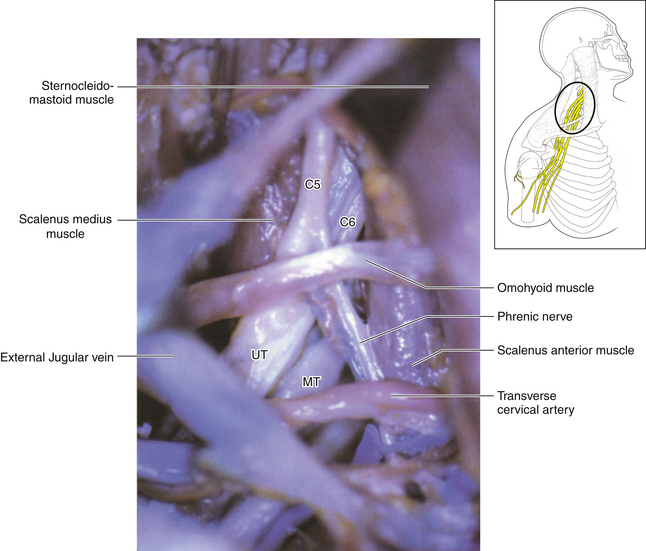

• The root of the neck can be a difficult and frightening arena for the inexperienced surgeon. Any structure can be chosen by the surgeon as the key to understanding this region. We use the scalenus anterior for this purpose, because the surgeon can easily palpate the characteristic anterior surface of that muscle through fat and scar tissue (Figure 2-15).

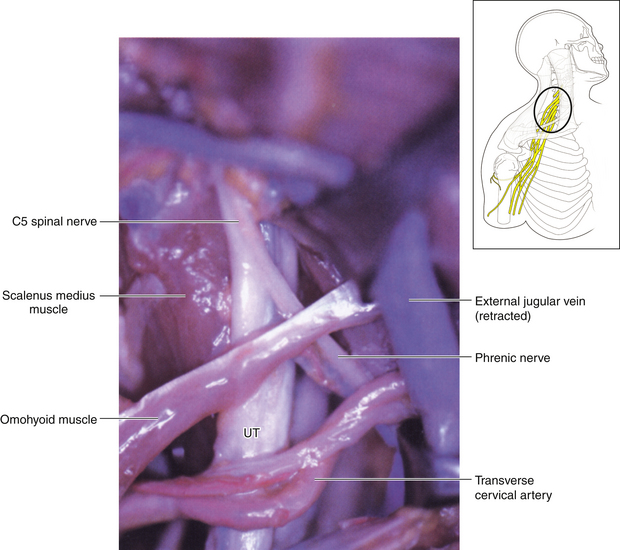

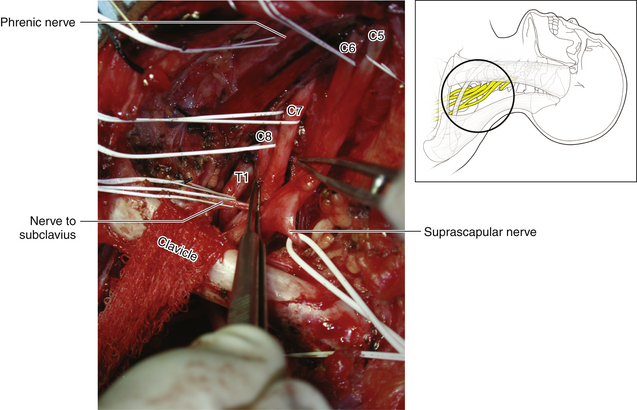

• The scalenus anterior originates from the anterior tubercles and is inserted via a short tendon into the first rib. The phrenic nerve runs downward from lateral to medial on its anterior surface. Laterally, the spinal nerves and trunks of the brachial plexus are seen (Figure 2-16).

• The medial border of the scalenus anterior bounds a triangular space. The other borders are the subclavian artery and the lateral border of the longus colli. The contents of the space include the stellate ganglion, the vertebral artery, the thyrocervical vessels and their branches, the suprapleural membrane, and the pleura.

• The fascial planes should be clearly understood. The investing fascia, having split to enclose the SCM, roofs the posterior triangle and splits to enclose the trapezius. The prevertebral fascia covers the scalenus anterior, the subclavian artery, and the brachial plexus and continues into the axilla.

Figure 2-6 A lateral view depicts the relationship of the relevant fascia and musculature to each other.

Surgery

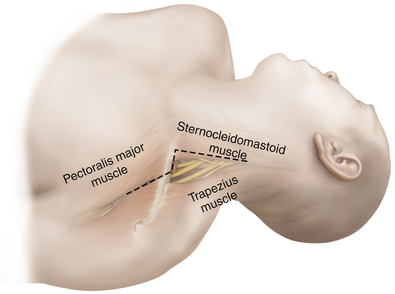

• The table is flexed at the patient’s waist so that the neck veins are not engorged. The chin is turned away from the operator. The neck is slightly extended. The surgeon may stand either on the side of the patient’s axilla or outside the deltoid. In either event, the patient’s shoulder must be free for shrugging or depressing during surgery, thus moving the clavicle if it is obstructing the surgeon’s view (Figure 2-17).

• The vertical limb of the skin incision follows the posterior border of the SCM. In the majority of cases, neither the cervical plexus nor CN XI is dissected, but the skin incision must be sufficiently high to view C5. The skin incision can be marked and draped for vertical extension, if more cephalad dissection is later required (Figure 2-11).

• The lower point of the vertical incision should be just above the clavicle. If it is anticipated that C8 and T1 will be dissected, the skin incision should be carried more medially before swinging laterally (Figure 2-11).

• The horizontal component of the incision is parallel to and above the clavicle and is then continued down over the cephalic vein (Figure 2-18).

• Once the skin and platysma have been incised, the fascia on the posterior border of the SCM is sharply incised, hard against the muscle (Figure 2-19).

• A fatty fibrous pad is then encountered. The surgeon palpates through this fat with the index finger, feeling the characteristic anterior surface of the scalenus anterior. This is an important step, because the novice tends to operate both too far laterally and too far superiorly and thus has difficulty finding the plexus (Figure 2-20).

• The surgeon knows that the phrenic nerve, in front of the scalenus anterior, is deep to the prevertebral fascia, so the fatty pad can be mobilized with dispatch, usually in an upward and lateral direction. Branches of the thyrocervical trunk will be encountered at several points in the dissection and should be divided if they get in the way (Figure 2-21).

• The external jugular vein may be retracted or divided if it is obstructive (Figure 2-22; see also Figure 2-21).

• The omohyoid is mobilized, and a sling is passed around the tendon. The muscle is drawn away from the field (usually upward).

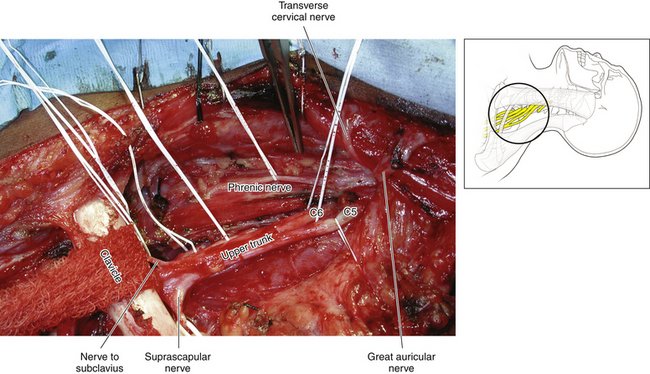

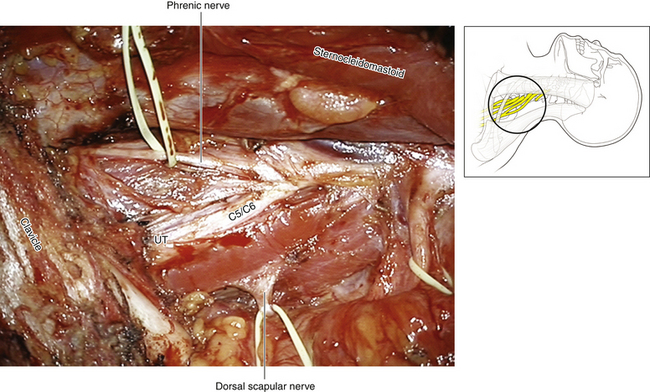

• The phrenic nerve is accurately mobilized and gently tented forward as the surgeon dissects upward (throughout the operation, the surgeon must remain vigilant of the dissected phrenic nerve, so that inadvertent traction is not applied to this crucial structure while attention is focused elsewhere) (Figure 2-23). The phrenic nerve leads to the C5 spinal nerve (Figures 2-24 and 2-25).

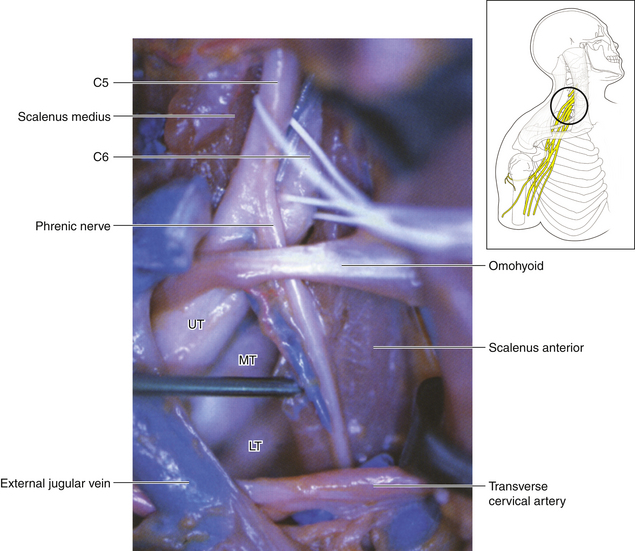

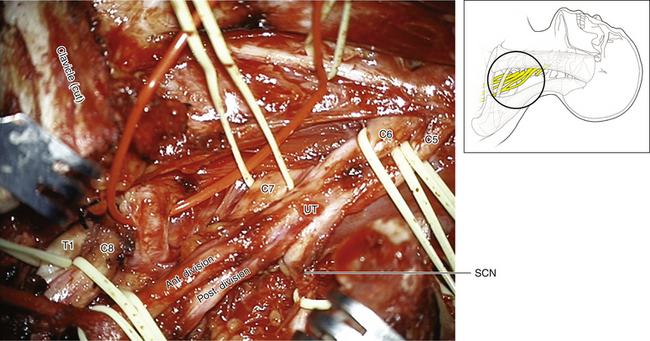

• C5 enters the posterior triangle by running posterior to the scalenus anterior and anterior to the scalenus medius. No matter how dense the scar, the anterior tubercles can be palpated and C5 can be dissected at this point (Figure 2-26).

• On rare occasions, it may be necessary to nibble the anterior tubercle away and resect the slips of scalenus anterior, so as to completely dissect out the spinal nerve up to the intervertebral foramen. At this point, venous oozing is a nuisance and is controlled by judicious cautery and packing.

• The dorsal scapular nerve leaves C5 proximally. If stimulation of C5 results in levator scapulae contraction, the welcome inference is that axons are viable to at least that point and that grafts can be led from there, if necessary (see Figure 2-24).

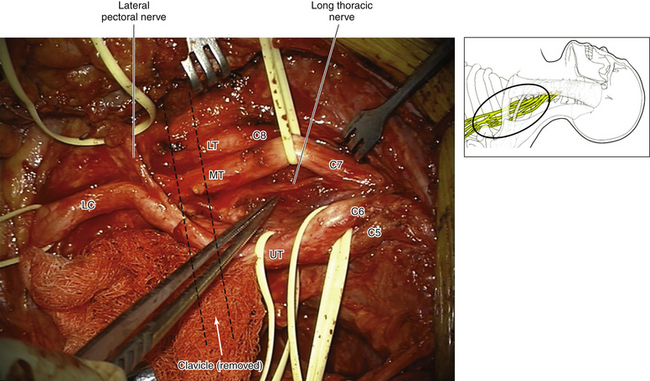

• The long thoracic nerve forms within the substance of the scalenus medius. Tenting C6 and C7 gently forward will reveal that spinal nerve contribution leaving the posterior aspect of the spinal nerve (Figure 2-27).

• The confluence of C5 and C6 is a very reliable landmark. Together, C5 and C6 establish the plane, and C7, C8, and T1 can, in turn, be dissected (see Figure 2-26).

• If it is anticipated that C8 and T1 will be dissected, the surgeon must make the appropriate adjustment to the exposure. A finger is passed immediately behind the lateral attachment of the SCM to the clavicle, to ensure that the veins are not stuck to the deep surface of the muscle. The lateral one and a half inches of the SCM are detached from the clavicle, leaving a small cuff for subsequent reapproximation (see Figure 2-13).

• After the dissected phrenic nerve is gently displaced and preserved, an instrument is passed behind the inferior attachment of the scalenus anterior and the muscle is divided horizontally. The severed ends spring apart and small bleeders are dealt with. This muscle is not resutured at the end of the operation.

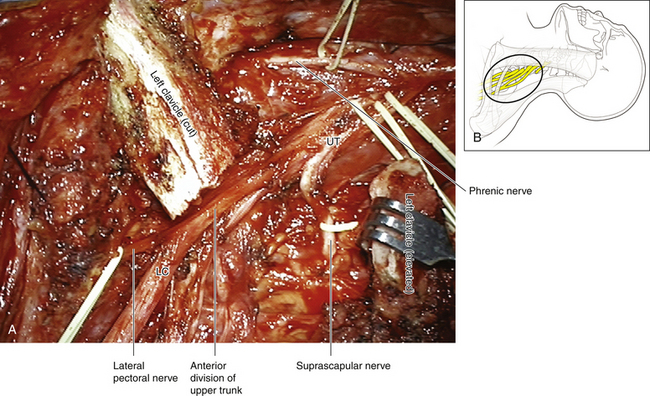

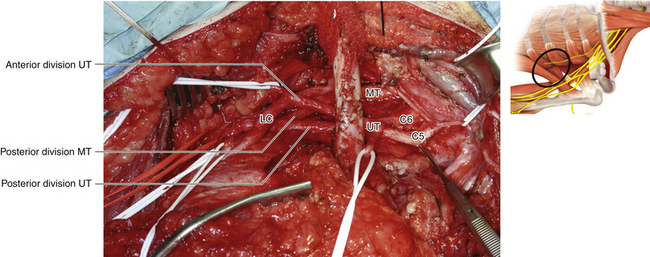

• The upper trunk and suprascapular nerve are dissected laterally. The length of the upper trunk is variable, and it terminates into anterior and posterior divisions (see Figures 2-7 and 2-27).

• The middle trunk is a continuation of C7 and can also be dissected to its divisions (Figures 2-28 and 2-29).

• The surgeon sweeps the pad of the index finger backward and medially along the upper border of the first rib. This pushes the suprapleural membrane and pleura away. In front of the neck of the first rib, the stellate ganglion is palpated.

• If the pleura is inadvertently breached, a catheter is passed through the rent, a purse-string suture is placed in the pleura, the anesthetist performs a Valsalva maneuver on the patient, and the catheter is withdrawn as the purse string is closed.

• A vein retractor or an encircling sponge pulls directly on the clavicle, and an assistant pulls the arm down to depress the clavicle (Figure 2-30; see also Figure 2-28).

• The subclavian artery is gently pulled forward and down, displaying the thyrocervical trunk. Usually, this vessel or its branches tether the subclavian artery; therefore the thyrocervical trunk is divided, allowing mobilization of the subclavian artery, to view the lower trunk of the plexus. The vertebral artery is identified and protected.

• These maneuvers allow clear access to C8 and T1, which embrace the neck of the first rib to form the lower trunk. The lower trunk, on occasion, is tucked behind the artery and difficult to dissect. If this is an important part of the dissection in a particular patient, an infraclavicular dissection is needed (Figure 2-31).

• An inch and a half of the lateral origin of the pectoralis major is divided from the clavicle. The clavipectoral fascia (between the clavicle and pectoralis minor) is incised and the medial cord/lower trunk is dissected.

• If the wound suddenly fills with chyle, the offending leaking structures should be meticulously closed, usually by bipolar coagulation, before proceeding with the operation. Close to their confluence with the venous system, the thoracic and other lymph ducts may appear venous because of reflux of blood into the lymph duct (Figure 2-32).

• Wound closure should be particularly meticulous, as platysma contraction may cause gaping scars.

Figure 2-28 The clavicle is displaced inferiorly by pulling down on the arm and on the sponge around the bone.

Infraclavicular Brachial Plexus

Anatomy

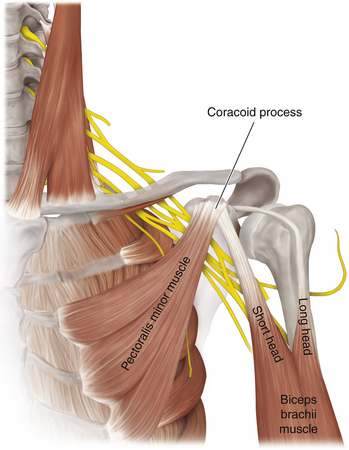

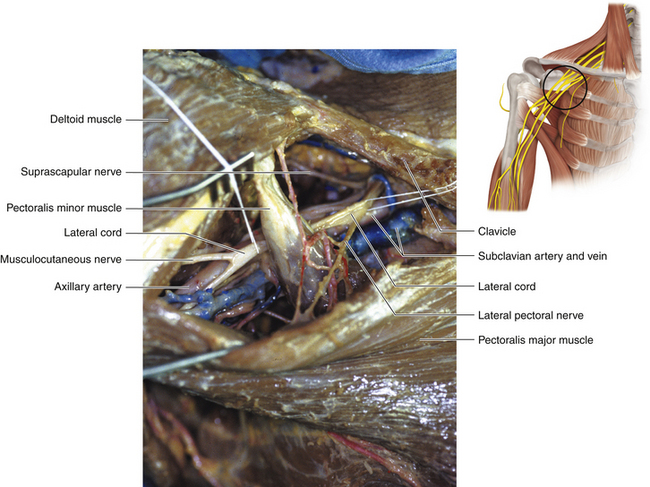

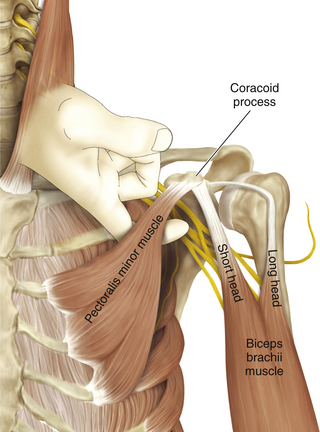

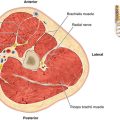

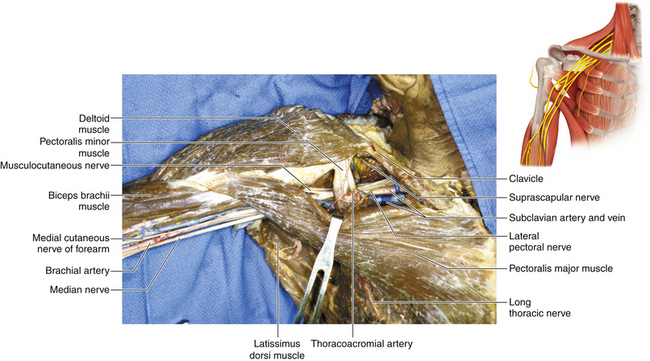

• The coracoid process of the scapula should be studied with care. The coracobrachialis and the short head of biceps originate from this prominence and the pectoralis minor inserts into it. No matter how dense the scarring is, the coracoid can always be palpated throughout axillary surgery. Its level is a guide to both the musculocutaneous and axillary nerves (Figure 2-33).

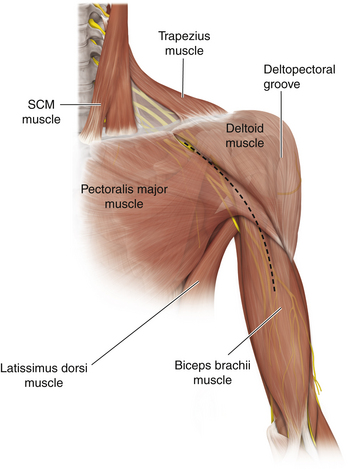

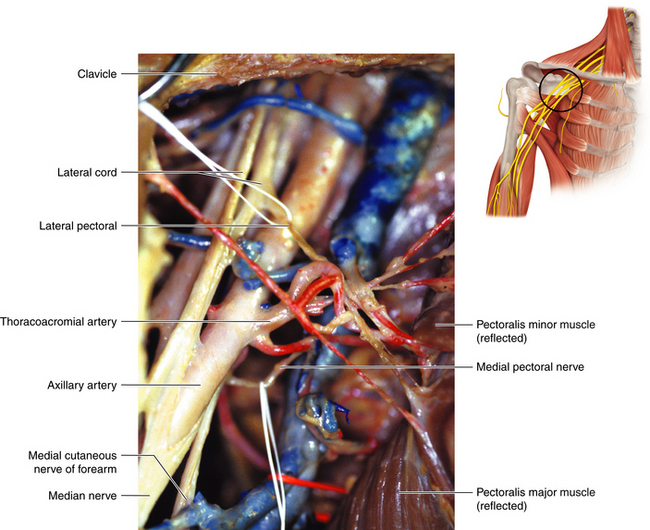

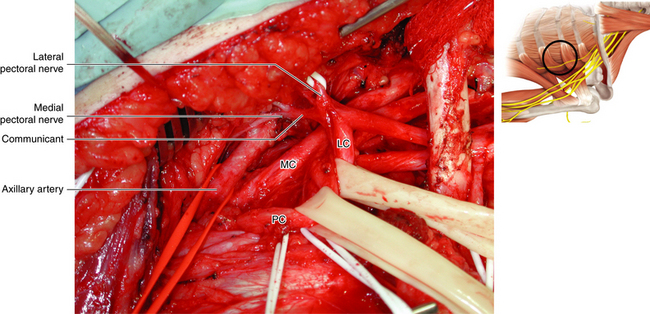

• The pectoralis major is a complex muscle, and the nerve surgeon should appreciate its clavicular origin—the clavipectoral fascia in the interval between the deltoid and the pectoral origin from the clavicle—and the trilaminar tendon of its insertion into the humerus (Figures 2-34 and 2-35). The muscle is supplied by the lateral and medial pectoral nerves (Figure 2-36).

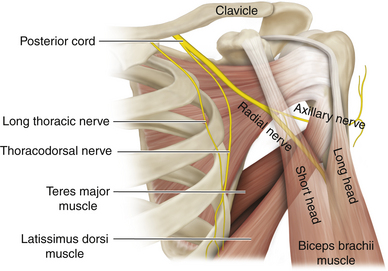

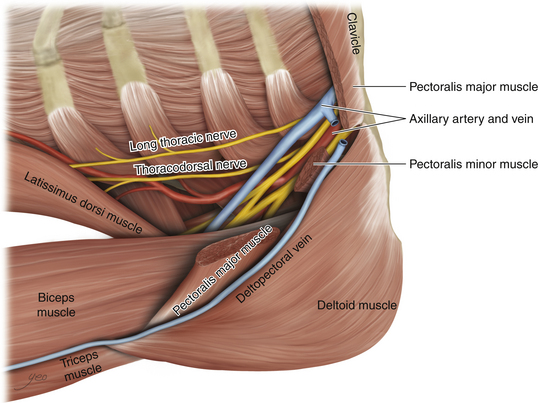

• The latissimus dorsi is an enormous muscle; the key point here is the formation of its thin shiny tendon, which curls around to insert into the intertubercular (bicipital) groove of the humerus, thus constituting the lower end of the posterior wall of the axilla (Figure 2-37).

• The teres major is covered by the tendon of latissimus dorsi when viewed from the front. Its origin, insertion, and nerve supply should be mastered (Figure 2-38).

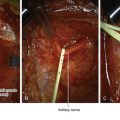

• The axillary artery enters the apex of the axilla by running over the first rib, behind the insertion of scalenus anterior. This vessel changes its name to the brachial artery as it leaves the lower border of the axilla (Figure 2-39).

• The major veins are respected during surgery, but smaller, horizontal veins can be divided (Figure 2-40).

Surgery

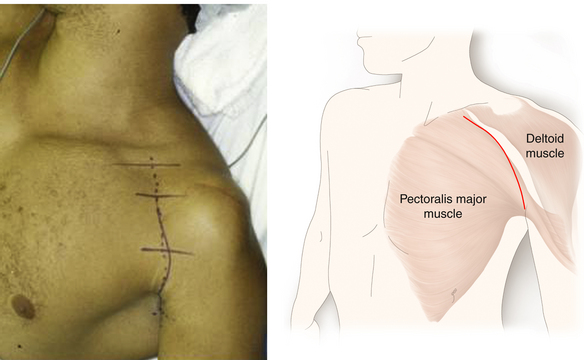

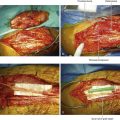

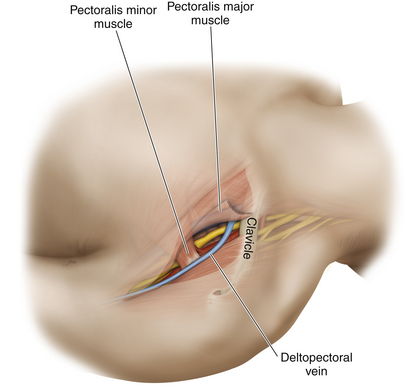

• Frequently, both the supraclavicular and infraclavicular exposures are combined (Figures 2-41 and 2-42). If, however, the surgeon is certain that the pathology is solely in the axilla, then the skin incision can start at the clavicle and continue over the deltopectoral (cephalic) vein to the level of the inferior insertion of the pectoralis major. At that point, the incision is brought posteriorly to lie over the brachial artery (Figures 2-43 and 2-44).

• The surgeon can be positioned either medial or lateral to the arm; however, it is essential that the limb be draped in such a way that the shoulder can be elevated or the arm pulled down, thus moving the clavicle out of the way during the plexus dissection.

• The skin incision is deepened to expose the tendinous insertion of the pectoralis major (Figure 2-45). The cephalic vein is the guide. The fascia over the free upper border of the pectoralis major is incised, protecting the lateral pectoral nerves.

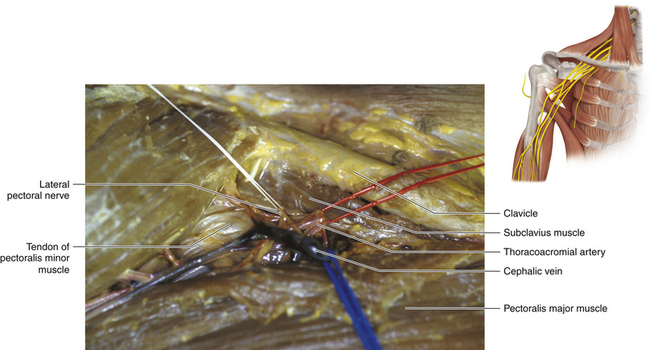

• The cephalic vein dives through the clavipectoral fascia and thus crosses the line of attack. This vessel is divided (Figure 2-46; see also Figure 2-36)

• A finger is inserted behind the pectoralis major tendon, close to the bone, from above and below. If a limited exposure is anticipated, as for a focal injury, only part of the tendon need be divided. Where appropriate, a sponge can be passed around the muscle to retract it (Figure 2-47). In most cases of severe stretch injury, however, the entire tendon is divided, leaving a cuff on the humerus for future reapproximation. The corners are marked with heavy sutures to allow careful reapproximation at the end of the case (Figure 2-48).

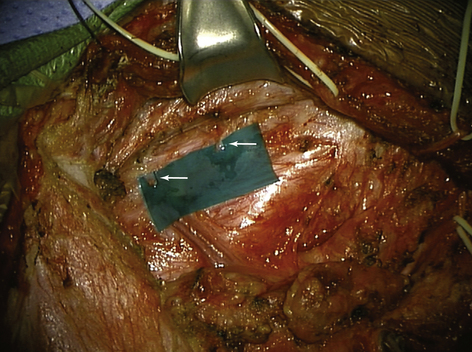

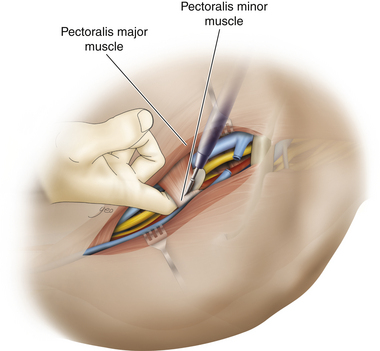

• In a few cases of focal injury, it may be possible to isolate the pectoralis minor tendon and pull it up or down to expose the underlying pathology (Figure 2-49). In the majority of cases, however, the tendon is divided close to the bone and self-retaining retractors are placed to retract both minor and major muscles in a medial direction (Figures 2-50 and 2-51).

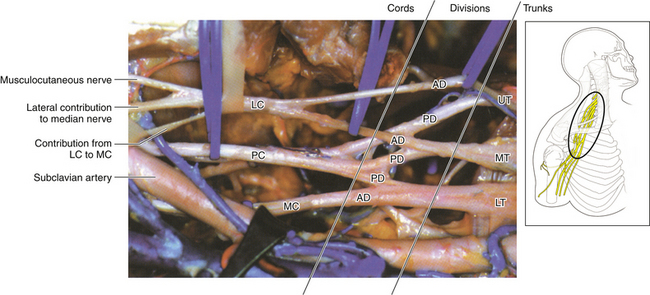

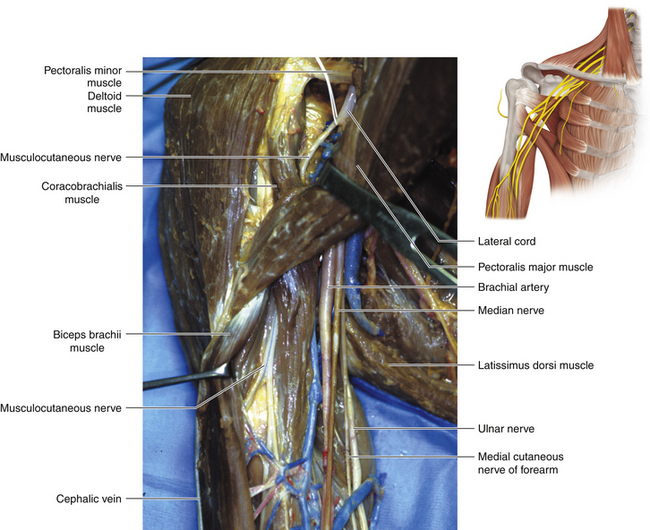

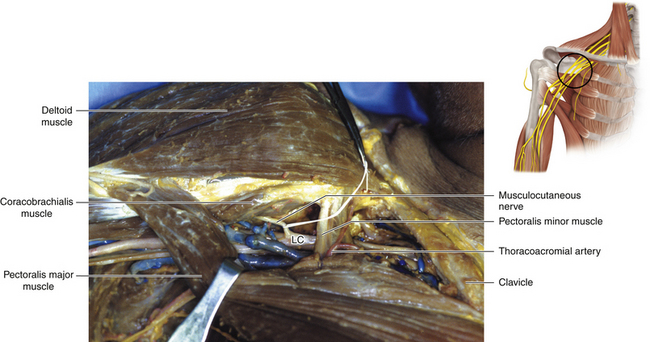

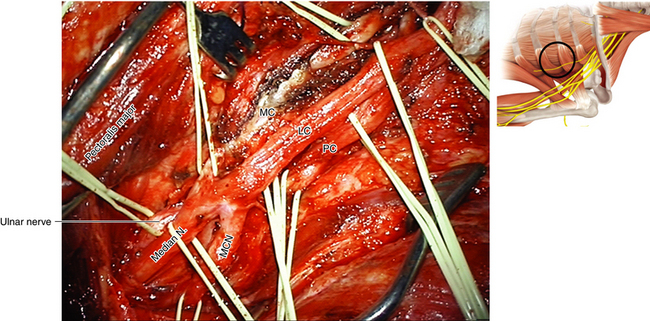

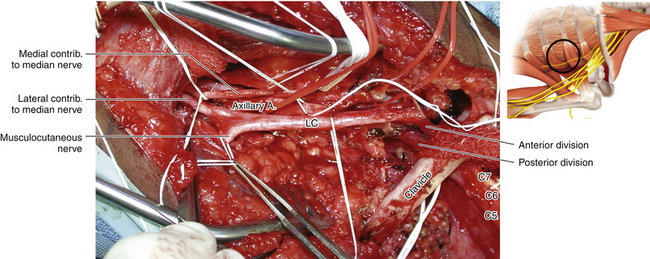

• Usually the first structure encountered is a lateral cord. It is dissected downward, thus identifying the takeoff of the musculocutaneous nerve and the lateral contribution to the median nerve (Figures 2-52 and 2-53).

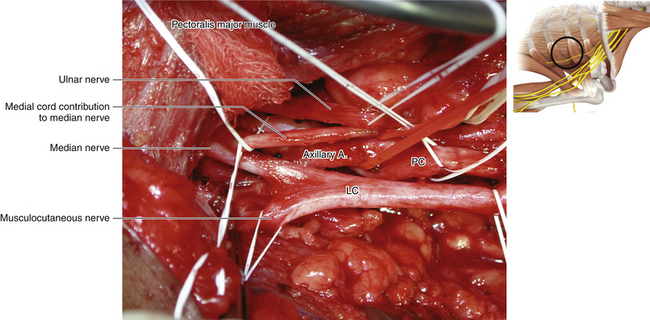

• The medial contribution to the median nerve is then followed up to display the two cutaneous nerves and the larger, more posteriorly located, ulnar nerve (Figure 2-54).

• The axillary artery is drawn into a straight line when the shoulder is abducted; the medial head of the median nerve is loosely applied to the vessel as it crosses laterally in front of the artery to join the lateral head (Figures 2-55 and 2-56). Not uncommonly, supplementary connections between the two heads and their cords of origin are present, and these should not be allowed to confuse the inexperienced surgeon.

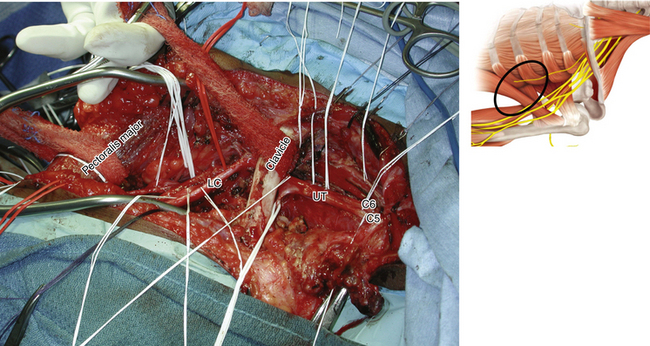

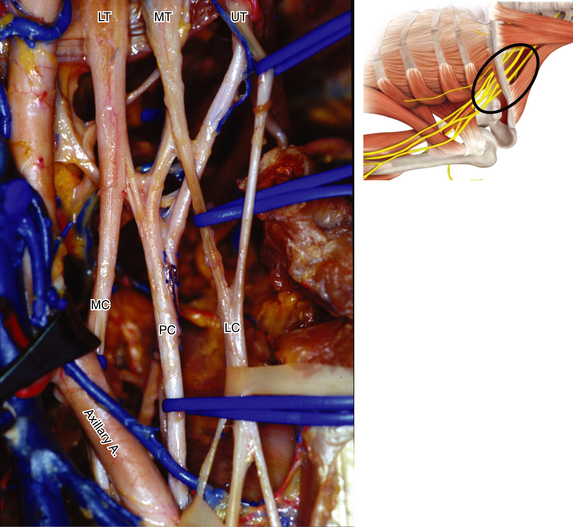

• The nomenclature of the cords refers to their relationship to the axillary artery at the level of the pectoralis minor tendon (Figure 2-57). In fact, the medial cord may be tucked more posteriorly, behind the medial border of the axillary artery. The medial cord is cleared up to the first rib. If this dissection is obscured, the lateral 1½ inches of the pectoralis major origin from the clavicle should be divided.

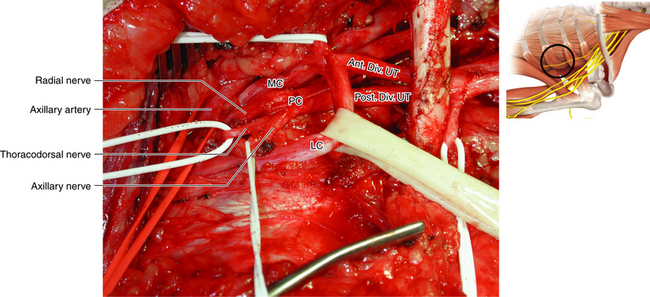

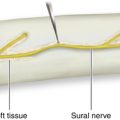

• The tapelike posterior cord is formed from the posterior divisions of all three trunks (Figure 57). It can be dissected out by operating from both the medial and lateral sides of the artery (Figures 2-58 and 2-59). In the lateral case, the surgeon must be conscious of the musculocutaneous nerve; it is good idea to separate the origin of the musculocutaneous nerve from the lateral cord for 1 inch so that the nerve is never under tension while the surgeon concentrates attention to the back of the axilla.

• If there is pathology involving the divisions, the problem must be sorted out by working both above and below the clavicle while that bone is displaced accordingly.

• The surgeon should be aware that the nerve to the latissimus dorsi may originate from either the posterior cord or the origin of the axillary nerve. With the arm adducted, the thoracodorsal nerve is stretched; it should be guarded while working on the posterior cord.

• Muscular branches to the triceps may arise close to the cord–radial nerve junction and should be guarded.

• A constant arterial branch (the profunda brachii) accompanies the radial nerve.

• Gently tenting the artery forward will reveal the posterior circumflex artery. This artery is a useful guide, because it runs down to the quadrangular space and helps to point the way to the axillary nerve, which may well be encased in dense scar.

• The medial and lateral pectoral nerves are named according to their cords of origin. These nerves should be guarded. If the medial pectoral nerves are used as donor nerves, the lateral pectoral nerve must be cared for with even greater vigilance.

• If necessary, a segment of the subclavius is resected to gain better access. An opened surgical sponge can be passed around the clavicle and clamped with a large instrument. A strong assistant can use the instrument as a handle and pull the clavicle forward. Experienced surgeons very rarely divide the clavicle, as exposure can be gained by the various methods that have been described for displacing this structure.

• If the clavicle is divided, the surgeon should ask an orthopedic colleague what the current fashion of clavicular repair is. There are numerous maneuvers, which indicates that none is entirely satisfactory (plate and screws, compression screw, wire, etc.). The skin must be closed with particular care over the repaired clavicle. It is most upsetting to be confronted with a chronic wound, with a plate shining in its depth, after otherwise successful plexus surgery.

• Repair of the pectoralis tendon at the conclusion of surgery must be carefully performed, encompassing the full thickness of the tissues on both sides. If this is not done, the powerful muscle will later tear away in part, with both functional and cosmetic sequelae.

• The superficial tissues and skin closure must be meticulous, or the scar will broaden in an ugly fashion.

Figure 2-41 Positioning and skin incision for both supraclavicular and infraclavicular brachial plexus surgery.

Figure 2-44 The deltopectoral (cephalic) vein is an excellent guide to further dissection after skin incision.

Figure 2-46 The deltopectoral (cephalic) vein is divided as it dives through the clavipectoral fascia.

Figure 2-48 The neurovascular structures covered by the pectoralis major and minor are displayed in the dissecting room.

Figure 2-53 The clavicle is retracted superiorly to reveal the division-cord junction. LC, Lateral cord.