Part 5: Aging

93e |

World Demography of Aging |

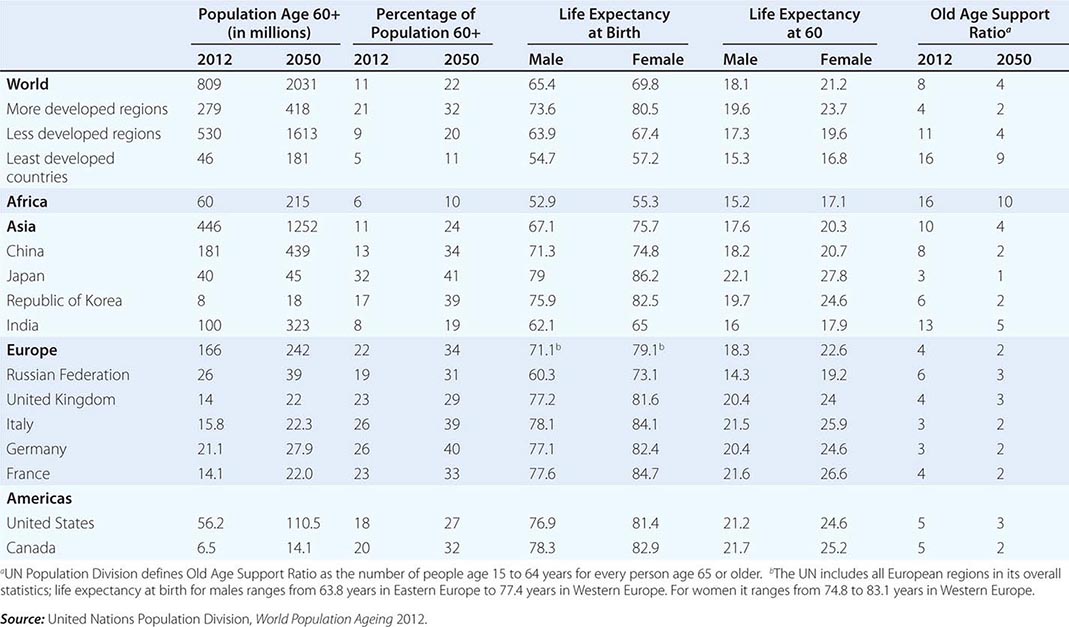

Population aging is transforming the world in dramatic and fundamental ways. The age distributions of populations have changed and will continue to change radically, due to long-term declines in fertility rates and improvements in mortality rates (Table 93e-1). This transformation, known as the Demographic Transition, is also accompanied by an epidemiologic transition, in which noncommunicable chronic diseases are becoming the major causes of death and contributors to the burden of disease and disability. A concomitant of population aging is the change in key ratios expressing “dependency” of one form or another—the ratio of adults in the workforce to those typically out of the workforce, such as infants, children, retired “young old” (those still active but in ways other than paid work), and the oldest old. Global aging will affect economic growth, migration, patterns of work and retirement, family structures, pension and health systems, and even trade and the relative standing of nations. Both absolute numbers (the size of an age group) and ratios (the ratio of those in working ages to dependents such as the young or retired, or the ratio of children to older people) are important. The size of age groups might affect the number of hospital beds needed, whereas the ratio of children to older people could affect the relative demand for pediatricians and geriatricians.

|

SELECTED INDICATORS OF POPULATION AGING, ESTIMATES FOR 2009, AND PROJECTIONS TO 2050; SELECTED REGIONS AND COUNTRIES |

Although the increase in life expectancy, resulting from a series of social, economic, public health, and medical victories over disease, might very well be considered the crowning achievement of the past century and a half, the increased length of life coupled with the shifts in dependency ratios present formidable long-term challenges.

The pace of the change is accelerating. In countries where the Demographic Transition began earlier, the process was slower: it took France 115 years for the proportion of the age group 65 and older to increase from 7 to 14% of the total population, and the United States will soon have completed this same increase in 69 years. But in countries that started the transition later, the process is occurring much more rapidly: Japan took 26 years to go from 7 to 14% age 65 and older, while China and Brazil are projected to require just 24 years.

Sometime around the year 2020, for the first time ever, the number of people age 65 and older in the world is expected to exceed that of children under the age of 5. Around the middle of the twentieth century, the under-5 age group constituted almost 15% of the total population and the over-65 age group 5%. It took about 70 years for these two to reach equal proportions. But demographers predict it will take only another 25–30 years for the 65 and older age group to equal about 15% and be about double the number of children under age 5. By the middle of their careers, medical students in most countries should expect to be practicing in far older populations. Preparations for these changes need to begin decades in advance, and the costs and penalties for delay can be very high. Although some governments have started planning for the long term, many, if not most, have yet to begin.

HISTORICAL

Population aging around the world in recent decades has followed a broadly similar pattern, starting with a decline in infant and childhood mortality that precedes a decline in fertility; at later stages, mortality at older ages declines as well. Declining fertility began as early as the beginning of the nineteenth century in the United States and France and extended to the rest of Europe and North America and parts of East Asia by the middle of the twentieth century. Since World War II, fertility declines have started in all other world regions. In fact, more than half the world’s population now lives in countries or provinces with fertility rates below the replacement level of just over two live births per woman. Mortality rates also began to change, relatively slowly at first, in Western Europe and North America during the nineteenth century. At first, changes were most evident at the youngest ages. Improvements in water supply and sewage handling, as well as in nutrition and housing, accounted for most of the improvement before the 1940s, when antibiotics and vaccines and increasing education of mothers began to make a major impact. Since the middle of the twentieth century, the “Child Survival Revolution” has spread to all parts of the world. Children almost everywhere in the world are much more likely to reach late middle age now than in previous generations.

Especially since around 1960, mortality at older ages has improved steadily. This improvement has been primarily due to advances in care of heart disease and stroke and in control of conditions like hypertension and hypercholesterolemia that lead to circulatory diseases. In some parts of the world, smoking rates have declined, and these declines have led to lower incidence of many cancers, heart disease, and stroke.

The initial decline in fertility resulted in older age groups becoming a larger fraction of the total population. Declines in adult and old age mortality contributed to population aging in the later stages of the process. Life expectancy at birth—the average age to which someone is expected to live, under prevailing mortality conditions—has been calculated at around 28 years in ancient Greece, perhaps 30 years in medieval Britain, and less than 25 years in the colony of Virginia in North America. In the United States, life expectancy climbed slowly during the nineteenth century, reaching 49 years for white women by 1900. White men had a life expectancy 2 years lower than that for white women, and black Americans had a life expectancy 14 years lower than did white Americans in 1900. By the early twenty-first century, life expectancy in the United States had improved dramatically for all, with the sex gap wider and the racial gaps narrower than at the beginning of the century: 76 years for white men in 2006; 81 years for white women; and 70 and 76 years for black men and women, respectively. However, although the United States had a relatively high life expectancy compared to other high-income countries around 1980, almost all such countries have in the interim exceeded the United States in life expectancy. Female life expectancy, especially for whites in the United States, has done particularly poorly, and this has been attributed to relatively high rates of lifetime smoking.

At later stages of the demographic transition, mortality declines at the oldest ages, leading to increases in the 65 and older population, and the oldest old, those older than age 85 years. Migration can also affect population aging. An influx of young migrants with high birth rates can slow (though not stop) the process, as it has in the United States and Canada; or the out-migration of the young leaving older people behind can accelerate aging at the population level, as it has in many rural areas of the world.

REGIONAL AGING—NUMBERS AND PERCENTAGES OLDER THAN AGE 60 YEARS

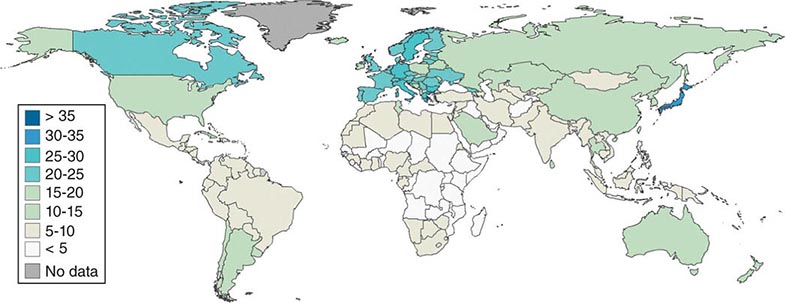

Regions of the world are at very different stages of the demographic transition (Fig. 93e-1). Of a world population of 6.8 billion in 2012, approximately 11% were older than age 60 years, with Japan (32%) and Europe (22%) being the oldest regions (Germany and Italy 27% each) and the United States having 19%. The percentage of the population older than age 60 years in the United States has remained lower than in Europe, due both to modestly higher fertility rates and to higher rates of immigration. Asia has about 10% older than age 60 years, with the population giants close to the average—China (12%), Indonesia (9%), and India (7%). Middle Eastern and African countries have the lowest proportions of older people (5% or lower).

FIGURE 93e-1 Percentages of national populations age 60+, in 2010. (From the U.S. Census Bureau, International Database. StatPlanet Mapping Software.)

Based on estimates from the United Nations Population Division, 809 million people were age 60 years or older in 2012, of whom 279 million lived in more developed countries and 530 million in less developed countries (as classified by the United Nations). The countries with the largest populations of those age 60 and older were China (181 million), India (100 million), and the United States (60 million).

NUMBERS—POPULATION SIZE PROJECTIONS

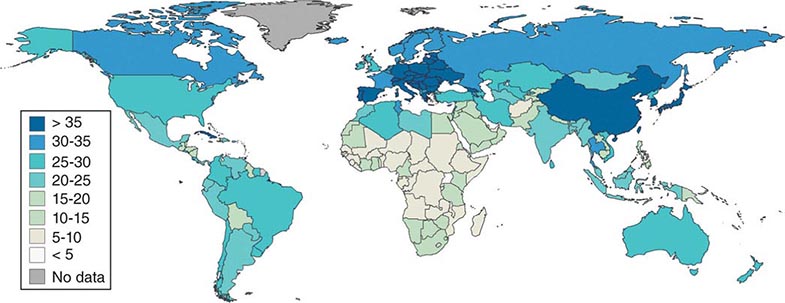

Population projections make use of expected fertility, mortality, and migration rates and should be regarded as uncertain when applied 40 or more years in the future. However, the population that will be age 60 and older in 2050 have all been born and survived childhood in 2014, so uncertainty about their numbers (as distinct from their proportion of the total population) is not great. Comparing the maps of the world in 2010 (Fig. 93e-1) and 2050 (Fig. 93e-2), it is apparent that the middle- and low-income countries in Latin America, Asia, and much of Africa will soon be joining the “oldest” category. In less than four decades between 2012 and 2050, the United Nations Population Division projects that the world population age 60 and older will more than double to 2.03 billion, with the least developed regions more than quadrupling. China’s 60+ population is projected to reach 439 million, India’s 323 million, and the United States’s 107 million. Over the same period, the median age of the world’s population is expected to increase by 10 years.

FIGURE 93e-2 Percentages of national populations age 60 +, in 2050 (projections). (From the U.S. Census Bureau, International Database. StatPlanet Mapping Software.)

Current global life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 65.4 for men and 69.8 for women, with the comparable figures for the more developed region being 73.6 and 80.5 years. Life expectancy in the least developed countries averaged only 57.2 for women and 54.7 for men. Life expectancy at birth is heavily influenced by infant and child mortality, which is considerably higher in poor countries. At older ages, the gap between rich and poor nations is narrower; so while women who have reached age 60 in wealthy countries can expect 23.7 more years of life on average, women at age 60 in poor countries live 16.8 years on average—a significant difference but not so stark as the difference in life expectancy at birth. At the lowest levels of per capita gross national product (GNP), life expectancy shows a powerful positive association with this measure of economic development, but then the slope of the relationship flattens out; for countries with average incomes above about $20,000 per year, life expectancy is not closely related to income. At each level of economic development, there is significant variation in life expectancy, indicating that many other factors influence life expectancy.

Japan, France, Italy, and Australia currently have some of the highest life expectancies in the world, while the United States has lagged behind other high-income countries since about 1980, especially in the case of white women. The causes of this lag are being explored, but the cumulative number of years that people have smoked tobacco by the time they reach older ages and the prevalence of obesity appear to play important roles.

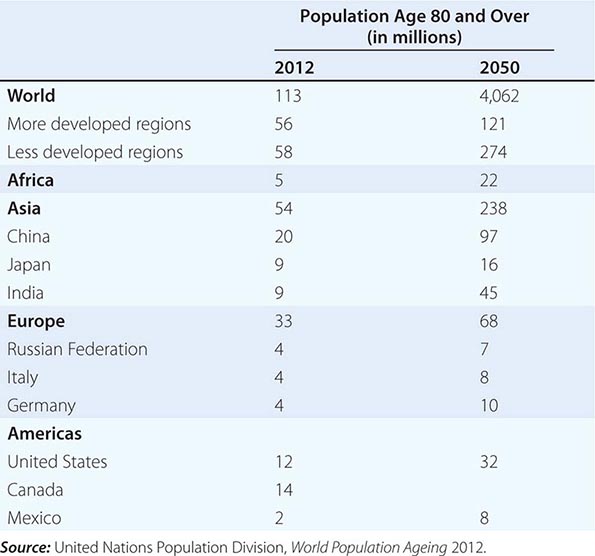

GROWTH OF THE OLDEST OLD POPULATION—THOSE OVER AGE 85

A modern feature of population aging has been the almost explosive growth of the age group known as the oldest old, variously defined as those over age 80 or age 85. This is the age group with the highest burden of noncommunicable degenerative disease and related disability. Thirty years ago, this group attracted little attention because they were hidden within the overall older population in most statistical reports; for example, the U.S. Census Bureau merged them into a 65+ category. The reduction of mortality at older ages coupled with larger birth cohorts surviving into old age led to the rapid growth of the oldest old. This age group is predicted to grow at a significantly higher rate than the 60+ population, and one estimate has the current 102 million age 80+ increasing to almost 400 million by 2050 (Table 93e-2). Projected increases are astounding: China’s 80+ population might increase from 20 to 96 million, India from 8 to 43 million, the United States from 12 to 32 million, and Japan from 9 to 16 million. The numbers of centenarians are increasing at an even faster rate.

|

ESTIMATES (2012) AND PROJECTIONS (2050) FOR THE POPULATION AGED 80 YEARS AND OLDER: SELECTED REGIONS AND COUNTRIES |

THE FUTURE OF LIFE EXPECTANCY

The members of the population who could potentially become age 80 and older in 2050 are already alive today. The actual numbers of people who will be age 80 and older in 2050 will therefore depend almost solely on adult and old age mortality rates over the next 35 years. The history of the decline of mortality suggests that improvements in the standard of living, including increased and improved education and improved nutrition, coupled with improvements in public health stemming from an understanding of the germ theory of disease initially led to the decline in mortality, with medical achievements such as antibiotics and improved understanding of risk factors for cardiovascular and circulatory diseases becoming factors only in the post–World War II period; the largest strides in cardiovascular disease came only in more recent decades. The improvements in educational attainment of succeeding generations have been credited in large part for improvements in child mortality during the past century, because educated mothers are especially likely to understand and take advantage of measures to reduce infection. The effects of continuing progress will likely be seen in coming decades as well, because educational attainment is associated with improved health and survival at older ages. Countries vary in the extent to which the “future elderly” cohorts will be more educated. China in particular will have a much more educated elderly population in 2050 (with more than two-thirds of the 65+ population having completed secondary school) than it did in 2000 (when only 10% of older people had a secondary education). In the United States and other rich nations, this change has largely taken place already; future changes in educational attainment of the elderly population will be less dramatic.

Holding aside the possibility of new infectious diseases ravaging populations as AIDS did in some African countries, debates about future life expectancy revolve around the balance and influence of risk factors such as obesity; the possibility of reducing the deaths from current killers such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes; whether there is some natural limit to life expectancy; and the distant though nonzero possibility that science will find a way to slow the basic processes of aging.

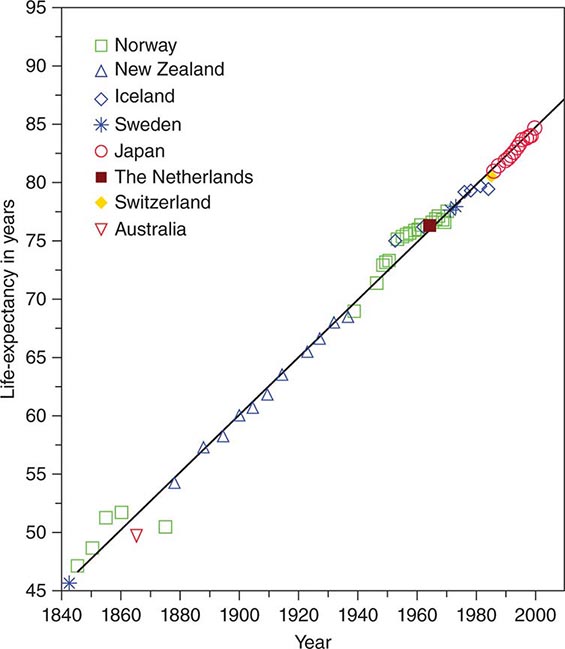

While some have posited natural limits to human life expectancy, the limits have been surpassed with some regularity, and at the very oldest ages in the leading countries with the highest life expectancy, there appears to be little evidence of any approaching asymptote. Indeed a surprising discovery was that life expectancy in the leading country over the last century and a half, with different countries taking the lead in different epochs, could be represented almost perfectly by a straight line, with the increase for females showing a steady and astonishing increase of three months per year or 2.5 years per decade (Fig. 93e-3). No single country kept that pace of improvement the entire time, but this trend calls into question the notion that improvement must slow down, at least in the near future.

FIGURE 93e-3 Life expectancy in most advanced nations, 1800–2000, females. (From J Oeppen, JW Vaupel: Science 296:1029, 2002.)

There remains a great deal of diversity in health conditions both among and within national populations. There is nothing inevitable about the mortality transition—in several African countries, the prevalence of AIDS has been high enough to cause life expectancy to fall below the levels of 1980. Though none has so far reached a scale to rival the AIDS epidemic, periodic outbreaks of new influenza viruses or “emerging infectious” agents remind us that infectious diseases could again come to the fore. Progress against chronic disease is also reversible: In Russia and some other countries that formed part of the Soviet Union before 1992, life expectancy for men has been declining, now reaching levels below those of men in South Asia. Much of the gap between Russian and Western European men is explainable by much greater heart disease and injuries among the former.

DEPENDENCY AND CAREGIVING RATIOS

Ratios of different age groups provide useful though crude indicators of potential demands on resources and resource availability. One set of ratios, known variously as dependency or support ratios, compare the age groups who are most likely to be in the labor force with the age groups typically dependent on the productive capacity of those working—the young and the old, or just the old. A commonly used ratio is the number of persons age 15–64 per persons age 65 and older. Even though many in some countries do not enter the labor force until significantly older than age 15, retire before age 65, or work past age 65, the ratios do summarize important facts, especially in countries where financial support for the retired comes partially or mainly from those currently in the labor force through either a formal pension system or through informal support from the family. While many countries still have very basic pension systems with incomplete coverage, in Europe public pensions are quite generous, and these countries face dramatic changes in their ratios of working age to older populations. Over the next 40 years, Western Europe faces a drop in the ratio from 4 to 2. In other words, while in crude terms there are today 4 workers supporting the pensions and other costs of each older person, by 2050 there will only be 2. China faces an even steeper drop from 9 persons of working age to only 3, while Japan declines from 3 to just 1. Even in India, projected to become the most populous country, the decline is quite steep from 13 to 5.

The dramatically declining number of workers per older person (however determined) is at the crux of the economic challenge of population aging. The extra years of life that can be considered the crowning achievement in medicine and public health of the last 150 years have to be financed. The economic model of the life cycle assumes that people are economically productive for a limited number of years and that the proceeds of their work during those years have to be smoothed over to finance consumption during less economically productive ages, either within families or by institutions such as the state in order to provide for the young, the old, and the infirm. There are only so many ways to meet the challenge of an extended period of dependency, including increasing the productivity of those in the labor force, saving more, reducing consumption, increasing the number of years worked by increasing the age of retirement, increasing the voluntary nonmonetary productive contributions of the retired, and immigration of very large numbers of young workers into the “old” countries. Pressures to increase retirement ages in industrialized countries and to reduce benefits are increasing. But no single one of these measures can bear the full load of adaptation to population aging, since the changes would have to be so severe and disruptive as to be politically impossible. More likely, there will be some combination of these measures.

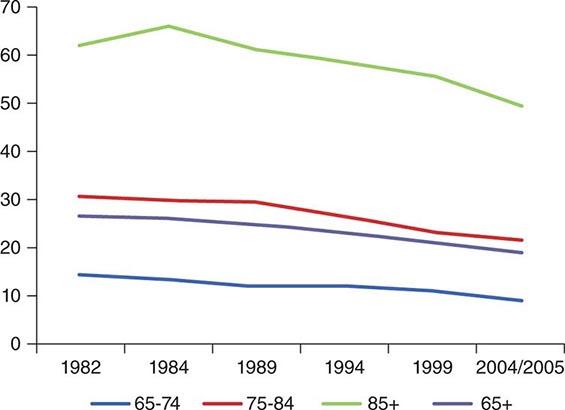

Population health and the ability to function at work and in everyday life interact with these population ratios in significant ways. The physical and cognitive capacity to continue to work at older ages is crucial if the age of retirement is raised. Similarly, caregiving often requires significant physical and emotional stamina. Further, healthier older populations require less caregiving and medical services. Just two decades ago, the prevalent view of aging was highly pessimistic. Epidemiologists held that while modern medicine could keep older people alive, nothing much could be done to prevent, delay, or significantly treat the degenerative chronic diseases of aging. The result would be that more and more older people with chronic diseases would be kept from dying, with the consequent piling up of the older people disabled by chronic disease. Surprisingly, between 1984 and about 2000, the prevalence of disability in the 65+ population in the United States declined by about 25%, suggesting that in this respect, aging was more plastic than had been previously believed (Fig. 93e-4). All the causes of this significant shift in disability are not yet understood, but rising levels of education, improved treatment of cardiovascular diseases and cataracts, greater availability of assistive devices, and less physically demanding occupations have been found to contribute. One calculation showed that if the rate of improvement could be maintained until 2050, that the numbers of disabled in the older population could be kept constant in the United States despite the aging of the baby boomers and the older population itself growing older. Unfortunately, the rapid increase in obesity rates could slow and perhaps even reverse this most positive trend. Because of the absence of comparable data in other countries, it is less certain whether the same pattern of improvement in disability rates (with recent deceleration) is occurring outside of the United States. Using estimates and projections of disease prevalence from the Global Burden of Disease Study, the global population of those “dependent and in need of care” is projected to rise from about 350 million in 2010 to over 600 million in 2050. Worldwide, about half of the older persons in need of care (two-thirds of the dependent population age 90 and above) suffer from dementia or cognitive impairment. A global network of longitudinal studies on aging, health, and retirement is now providing comparable data that may allow more definitive projections on disease and disability trends in the future. One estimate (World Alzheimer’s Report 2010) projected that the 36 million people with dementia worldwide in 2010 would increase to 115 million by 2050. The largest increases would occur in low- and middle-income countries where about two-thirds already live. The estimated costs were $604 billion in 2010 with 70% occurring in North America and Western Europe. A 2013 study using a nationally representative U.S. sample found that annual dementia costs could be as high as $215 billion. Direct costs of dementia care exceeded the direct costs for either heart disease or cancer. Given the age-associated prevalence of dementia and the expected increase in the older population, coupled with the associated decline in family members able to provide care, countries need to plan for a pandemic of individuals requiring long-term care.

FIGURE 93e-4 Disability prevalence, various years 1982–2005, by age group over 65, United States. (Adapted from KG Manton et al: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103:18374, 2006.)

Population aging, and related demographic changes including changes in family structure, could affect the “supply side” of long-term care as well as the demand for care and health care. In every country, long-term care of the disabled and the chronically ill relies heavily on informal, typically unpaid caregivers—usually spouses or children; and increasingly in more developed countries, caregivers for the oldest old are in their 60s and early 70s. Although there are many men who provide care, on the population level, informal caregiving is still mainly done by women. Because women live longer than men, lack of a spousal caregiver is especially likely to be a problem for older women. Both men and women have fewer children on whom they can call for informal caregiving, because of the worldwide decline in fertility rates. An increasing proportion of older men in Europe and North America have spent much or all of their adult lives apart from their biological children. Lower fertility rates, delayed marriage, and increasing divorce rates mean that people approaching old age may be less likely to have close ties with daughters and daughters-in-law—the adults who have in the past been the most common caregivers apart from spouses. Adult women who in the past have provided uncompensated care (and much other essential volunteer work) are now more likely than in the past to be working for pay and thus have fewer hours to devote to the unpaid roles.

These broad demographic and economic trends do not dictate particular social adaptations or policy responses, of course. One can imagine many different responses to the challenges of caring for the disabled—increased reliance on home health agencies and assisted living communities, “naturally occurring retirement communities” in which neighbors fulfill many of the roles once reserved for close kin; private or even publicly financed direct payments to compensate formerly unpaid family caregivers (a reform that has proved very popular in Germany). These and other responses to the challenge of long-term care are being tested in aging countries, and continued experimentation will no doubt be needed.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION—CHANGES IN THE BURDEN OF DISEASE AND RISK FACTORS

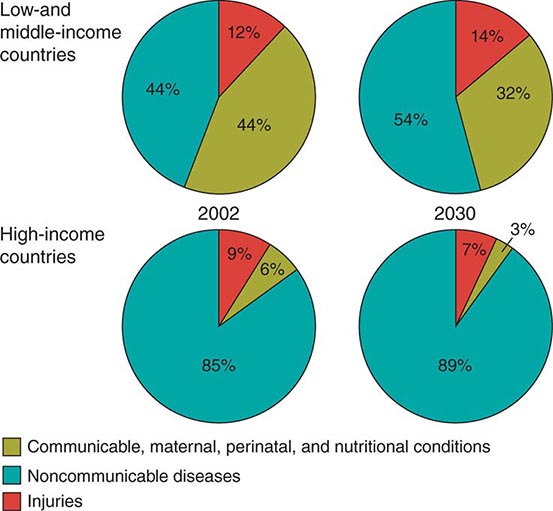

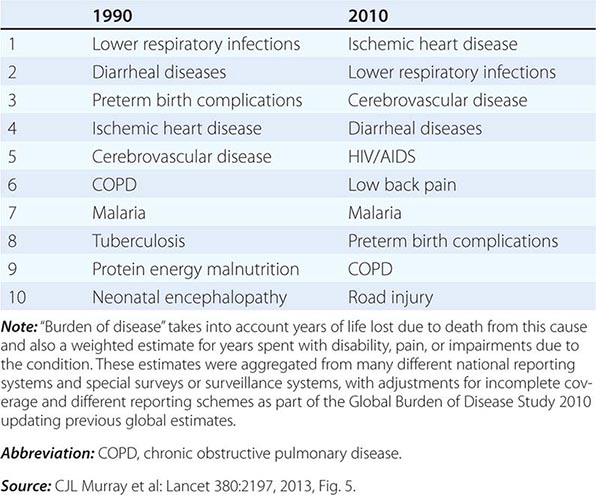

The secular improvements in ages at death have been accompanied by changes in causes of death. In the broadest terms, the proportion of deaths due to infectious disease and conditions associated with pregnancy and delivery has fallen, and the proportion due to chronic, noncommunicable diseases, such as heart and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers, and age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, has increased steadily and is expected to continue to increase. Figure 93e-5 shows results from an international comparative project that drew on a wide variety of data sources to provide estimates of the global burden of disease at the beginning of this century, with projections to future years based on recent trends in disease prevalence and demographic rates. Burden of disease in these pie charts is a composite measure, one that takes into account both the number of deaths due to a particular disease or condition and the timing of such deaths—an infant death represents a loss of more potential life-years lived than does the death of a very old person. Nor is death the only outcome that matters; most diseases or conditions cause significant disability and suffering even when nonfatal, so this measure of burden captures nonfatal outcomes using statistical weighting. As Table 93e-3 shows, the “modern plagues” of chronic noncommunicable diseases are already among the leading causes of premature death and disability even in low-income countries. This is due to a mix of factors—lower fertility rates mean fewer infants and children at prime ages of susceptibility to infections; more people reaching older ages when chronic disease incidence is high; and often changing incidence rates due to increased exposure to tobacco, Western diets, and inactivity. Noncommunicable diseases, once thought of as “diseases of affluence,” are projected to account for more than half of the disease burden even in low- and middle-income countries by the year 2030 (Fig. 93e-5).

|

RANKING OF DISEASES AND CONDITIONS CAUSING THE GREATEST BURDEN OF DISEASE WORLDWIDE IN 1990 AND 2010 |

FIGURE 93e-5 Leading causes of burden of illness in world regions 2002 and projected for 2030. (Adapted from CD Mathers, D Loncar: PLoS Med 3:e442, 2006.)

SUMMARY

Population aging is a global phenomenon with profound short- and long-term implications for health and long-term care needs, and indeed for the economic and social well-being of nations. The timing and context of aging vary across and within world regions and countries; the industrialized nations became wealthy before they aged significantly, while many of the low-resource regions will age before they reach high-income levels. The variation at both the population level and individual levels indicates that there is much flexibility in successful aging, but meeting the challenges will require advance planning and preparation. The extent to which research can find solutions that reduce physical and cognitive disability at older ages will determine how countries cope with this fundamental transformation.

94e |

The Biology of Aging |

THE IMPACT OF AGING ON MEDICINE

Aging and old age are among the most significant challenges facing medicine this century. The aging process is the major risk factor underlying disease and disability in developed nations, and older people respond differently to therapies developed for younger adults (usually with less effectiveness and more adverse reactions). Modern medicine and healthier lifestyles have increased the likelihood that younger adults will now achieve old age. However, this has led to rapidly increasing numbers of older people, often encumbered with age-related disorders that are predicted to overwhelm health care systems. Improved health in old age and further extension of the human healthspan are now likely to result primarily from increased understanding of the biology of aging, age-related susceptibility to disease, and modifiable factors that influence the aging process.

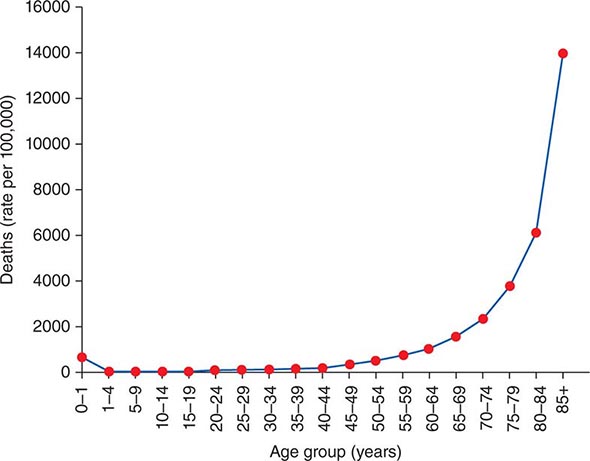

Definitions of Aging Aging is easy to recognize but difficult to define. Most definitions of aging indicate that it is a progressive process associated with declines in structure and function, impaired maintenance and repair systems, increased susceptibility to disease and death, and reduced reproductive capacity. There are both statistical and phenotypic components to aging. As recognized by Gompertz in the nineteenth century, aging in humans is associated with an exponential risk of mortality with time (Fig. 94e-1), although it is now realized that this plateaus in extreme old age because of healthy survivor bias. The phenotypic components of aging include structural and functional changes that are separated, somewhat artificially, into either primary aging changes (e.g., sarcopenia, gray hair, oxidative stress, increased peripheral vascular resistance) or age-related disease (e.g., dementia, osteoporosis, arthritis, insulin resistance, hypertension).

FIGURE 94e-1 The rates of death in the United States (2010) showing exponential increase in mortality risk with chronologic age.

Definitions of aging rarely acknowledge the possibility that some of those biological and functional changes with aging might be adaptive or even reflect improvement and gain. Nor do they emphasize the effect of aging on responses to medical treatments. Old age is associated with increased vulnerability to many perturbations, including therapeutic interventions. This is a critical issue for clinicians; the problem with aging would be more limited if our disease-specific therapies retained their balance of risk to benefit into old age.

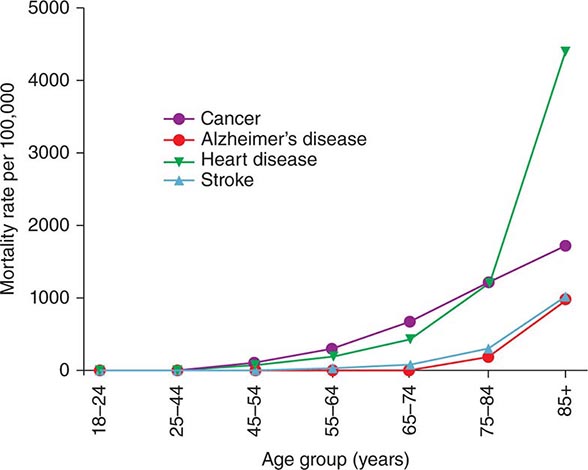

Aging and Disease Susceptibility Old age is the major independent risk factor for chronic diseases (and associated mortality) that are most prevalent in developed countries such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, and neurodegenerative disorders (Fig. 94e-2). Consequently, older people have multiple comorbidities, usually in the range of 5 to 10 illnesses per person.

FIGURE 94e-2 The rates of most common chronic diseases and related mortality increase with old age. (Data from USA 2008–2010 CDC.)

Disease in older people is typically multifactorial with a strong component related to the underlying aging process. For example, in younger patients with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is a single disorder confirmed by examining brain tissue for plaques and tangles containing amyloid and tau proteins. However, the vast majority of people with dementia are elderly, and here the association between typical Alzheimer’s neuropathology and dementia becomes less definitive. In the oldest-old, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s-type brain pathology is similar in people with and without clinical features of dementia. On the other hand, brains of older people with dementia usually show mixed pathology, with evidence of Alzheimer’s pathology along with features of other dementias such as vascular lesions, Lewy bodies, and non-Alzheimer’s tauopathy. Typical aging changes, such as microvascular dysfunction, oxidative injury, and mitochondrial impairment, underlie many of the pathologic changes.

The Longevity Dividend Compression of morbidity refers to the concept that the burden of lifetime illness might be compressed by medical interventions into a shorter period before death without necessarily increasing longevity. However, continuing development of successful therapeutic and preventative interventions focusing on individual diseases is less effective in older people because of multiple comorbidities, complications of overtreatment, and competing causes of death. Therefore, it has been proposed that further gains in healthspan and life expectancy will be achieved by a single intervention that delays aging and age-related disease susceptibility, rather than multiple treatments each targeting different individual age-related illnesses. This is called the longevity dividend and is driving an explosion of research into aging biology and, more importantly, interventions (genetic, pharmaceutical, and nutritional) that influence the rate of aging and delay age-related disease.

EVOLUTIONARY MECHANISMS FOR AGING

At the most basic level, living things have only two approaches to maintain their existence: immortality or reproduction. In a changing environment, reproduction combined with a finite lifespan has proved to be the successful strategy. Of course, finite lifespan is not the same as aging, although aging, by definition, contributes to a finite lifespan.

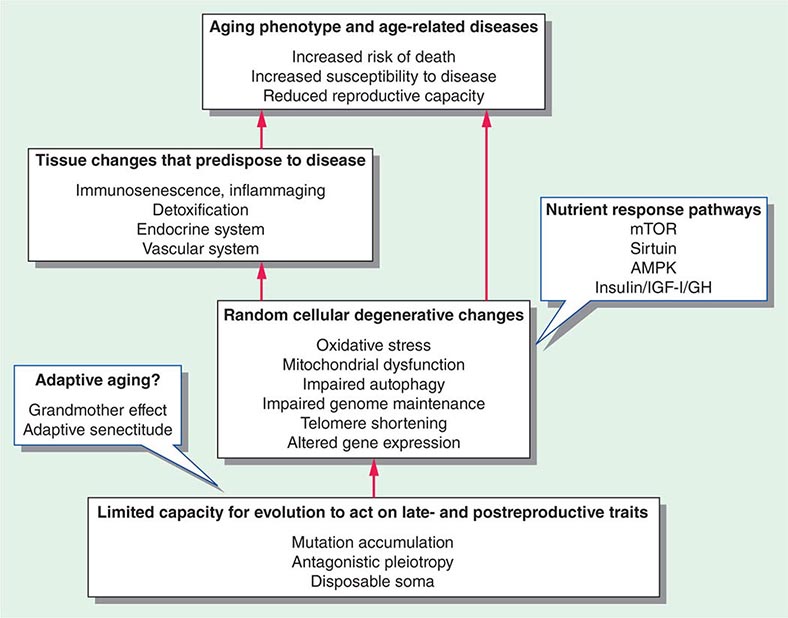

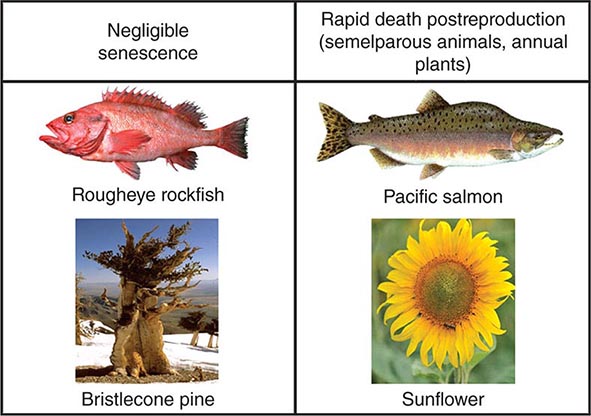

Many evolutionary theories related to aging are linked by their attempts to explain this interaction between reproduction and longevity (Fig. 94e-3). Most mainstream aging theories stem from the fact that evolution is driven by early reproductive success, whereas there is minimal selection pressure for late-life reproduction or postreproductive survival. Aging is seen as the random degeneration resulting from the inability of evolution to prevent it, i.e., the nonadaptive consequence of evolutionary “neglect.” This conclusion is supported by studies that restricted reproduction to later life in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, thus permitting natural selection to operate on later life traits and leading to an increase in longevity. There are some species of plants and animals that do not appear to age, or at least they undergo an extremely slow aging process, termed “negligible senescence.” The mortality rates of these species are relatively constant with time, and they do not display any obvious phenotypic changes of aging. Conversely, there are some living things that undergo programmed death immediately after reproduction, such as annual plants and semelparous animals (Fig. 94e-4). However, many other living things from yeast to humans undergo a gradual aging process leading to death that is surprisingly similar at the cellular and biochemical level across taxa. Some of the major classical evolutionary theories of aging include the following:

FIGURE 94e-3 Schema linking evolution and cellular and tissue changes with aging. The call-out blue boxes indicate factors that might delay the aging process including nutrient response pathways and, possibly, adaptive evolutionary effects.

FIGURE 94e-4 The typical features of aging (aging phenotype and exponential increase in risk of death) are not universal findings in living things. Some living things (e.g., rockfish and the bristlecone pine, sometimes called the Methuselah tree) undergo negligible senescence, whereas others die almost immediately after reproduction is completed (e.g., semelparous animals and annual plants).

• Programmed death. The first evolutionary theory of aging was proposed by Weissman in 1882. This theory states that aging and death are programmed and have evolved to remove older animals from the population so that environmental resources such as food and water are freed up for younger members of the species.

• Mutation accumulation. This theory was proposed by Medawar in 1952. Natural selection is most powerful for those traits that influence reproduction in early life, and therefore, the ability of evolution to shape our biology declines with age. Germline mutations that are deleterious in later life can accumulate simply because natural selection cannot act to prevent them.

• Antagonistic pleiotropy. George C. Williams extended Medawar’s theory when he proposed that evolution can allow for the selection of genes that are pleiotropic, i.e., beneficial for survival and reproduction in early life, but harmful in old age. For example, genes for sex hormones are necessary for reproduction in early life but contribute to the risk of cancer in old age.

• Life history theory. Evolution is influenced by the way that limited resources are allocated to all aspects of life including development, sexual maturation, reproduction, number of offspring, and senescence and death. Therefore, “trade-offs” occur between these phases of life. For example, in a hostile environment, survival is highest for those species that have large numbers of offspring and short lifespan, whereas in a safe and abundant environment, survival is highest for those species that invest resources in a smaller number of offspring and a longer life.

• Disposable soma theory. Kirkwood and Holliday in 1979 combined many of these ideas in the disposable soma theory of aging. There are finite resources available for the maintenance and repair of both germ and soma cells, so there must be a trade-off between germ cells (i.e., reproduction) and soma cells (i.e., longevity and aging). The soma cells are disposable from an evolutionary perspective, so they accumulate damage that causes aging while resources are preferentially diverted to the maintenance and repair of the germ cells. For example, the longevity of the nematode worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, is increased when its germ cells are ablated early in life.

All of these theories assume that natural selection has negligible or negative influences on aging. Some postmodern ideas propose that aspects of aging might be adaptive and raise the possibility that evolution can act on the aging process in a positive way. These include the following:

• Grandmother hypothesis. The grandmother hypothesis proposed by Hamilton in 1966 describes how evolution can enhance old age. In some animals, including humans, the survival of multiple, dependent offspring is beyond the capacity and resources of a single parent. In this situation, the presence of a long-lived grandmother who shares in the care of her grandchildren can have a major impact on their survival. These children share some of the genes of their grandmother including those that promoted their grandmother’s longevity.

• Mother’s curse. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key component of the aging process. Mitochondria contain their own DNA and are only passed on from mother to child because sperm cells contain almost no mitochondria. Therefore, natural selection can only act on the evolution of mitochondrial DNA in females. The “mother’s curse” of the maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA might explain why females live longer and age more slowly than males.

• Adaptive senectitude. Many traits that are harmful in younger humans such as obesity, hypertension, and oxidative stress paradoxically appear to be associated with greater survival and function in very old people. Perhaps driven by the grandmother effect, this might represent “adaptive senectitude” or “reverse antagonistic pleiotropy,” whereby some traits that are harmful in young people become beneficial in older people.

CELLULAR PROCESSES THAT ACCOMPANY AGING

There are many cellular processes that change with aging. These are generally considered to be degenerative and stochastic or random changes that reflect some sort of time-dependent damage (Fig. 94e-3). Whether any of these is the root cause of aging is unknown, but they all contribute to the aging phenotype and disease susceptibility.

Oxidative Stress and the Free Radical Theory of Aging Free radicals are chemical species that are highly reactive because they contain unpaired electrons. Oxidants are oxygen-based free radicals that include the hydroxyl free radical, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide. Most cellular oxidants are waste products generated by mitochondria during the production of ATP from oxygen. More recently, the role of oxidants in cellular signaling and inflammatory responses has been recognized. Unchecked, oxidants can generate chain reactions leading to widespread damage to biological molecules. Cells contain numerous antioxidant defense mechanisms to prevent such oxidative stress including enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) and chemicals (uric acid, ascorbate). In 1956, Harman proposed the “free radical theory of aging,” whereby oxidants generated by metabolism or irradiation are responsible for age-related damage. It is now well established that old age in most species is associated with increased oxidative stress, for example to DNA (8-hydroxyguanosine derivatives), proteins (carbonyls), lipids (lipoperoxides, malondialdehydes), and prostaglandins (isoprostanes). Conversely, many of the cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms, including the antioxidant enzymes, decline in old age. The free radical theory of aging has spawned numerous studies of supplementation with antioxidants such as vitamin E to delay aging in animals and humans. Unfortunately, meta-analyses of human clinical trials performed to treat and prevent various diseases with antioxidant supplements indicate that they have no effect on, or may even increase, mortality.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Aging is characterized by altered mitochondrial production of ATP and oxygen-derived free radicals. This leads to a vicious cycle mediated by accumulation of oxidative injury to mitochondrial proteins and DNA. With age, the number of mitochondria in cells decreases, and there is an increase in their size (megamitochondria) associated with other structural changes including vacuolization and disrupted cristae. These morphologic aging changes are linked with decreased activity of mitochondrial complexes I, II, and IV and decreased ATP production. Of all of the complexes involved in ATP production, the activity of complex IV (COX) is usually reported to be most impaired in old age. Reduced energy production is linked with generation of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals leading to oxidative injury to mitochondrial DNA and accumulation of carbonylated mitochondrial proteins and mitochondrial lipoperoxides. As well as being implicated in the aging process, common geriatric syndromes including sarcopenia, frailty, and cognitive impairment are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Telomere Shortening and Replicative Senescence Cells that are isolated from animal tissue and grown in culture only divide for a certain number of times before entering a senescent phase. This number of divisions is known as the Hayflick limit and tends to be less in cells isolated from older animals compared to younger animals. It has been suggested that aging in vivo might in part be secondary to some cells ceasing to divide because they have reached their Hayflick limit. One mechanism for replicative senescence relates to telomeres. Telomeres are repeat sequences of DNA at the end of linear chromosomes that shorten by around 50–200 base pairs during each cell division by mitosis. Once telomeres become too short, cell division can no longer occur. This mechanism contributes to the Hayflick limit and has been called the cellular clock. There are some studies that suggest that the length of telomeres in circulating leukocytes (leukocyte telomere length [LTL]) decreases with age in humans. However, the aging process also occurs in tissues that do not undergo repeated cell division such as neurons.

Altered Gene Expression, Epigenetics, and microRNA There are changes in the expression of many genes and proteins during the aging process. These changes are complicated and vary between species and tissue. Such heterogeneity reflects increasing dysregulation of gene expression with age while appearing to exclude a programmed and/or uniform response. With old age, there are often reductions in the expression of genes and proteins associated with mitochondrial function and increased expression of those involved with inflammation, genome repair, and oxidative stress. There are several factors controlling the regulation of gene and protein expression that change with aging. These include the epigenetic state of the chromosomes (e.g., DNA methylation and histone acetylation) and microRNAs (miRNA). DNA methylation correlates with age, although the pattern of change is complex. Histone acetylation is regulated by many enzymes including SIRT1, a protein that has marked effects on aging and the response to dietary restriction in many species. miRNAs are a very large group of noncoding lengths of RNA (18–25 nucleotides) that inhibit translation of multiple different mRNAs through binding their 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The expression of miRNAs usually decreases with aging and is altered in some age-related diseases. Specific miRNAs linked with aging pathways include miR-21 (associated with target of rapamycin pathway) and miR-1 (associated with insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 pathway).

Impaired Autophagy There are a number of ways that cells can remove damaged macromolecules and organelles, often generating cellular energy as a byproduct. Intracellular degradation is undertaken by the lysosomal system and the ubiquitin proteasomal system. Both are impaired with aging, leading to the accumulation of waste products that alter cellular functions. Such waste products include lipofuscin, a brown autofluorescent pigment found within lysosomes of most cells in old age and often considered to be one of the most characteristic histologic features of aging cells. They also include aggregated proteins characteristic of age-related neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., tau, β-amyloid, α-synuclein). Lysosomes are organelles that contain proteases, lipases, glycases, and nucleotidases that degrade intracellular macromolecules, membrane components, organelles, and some pathogens through a process called autophagy. The lysosomal process most impaired with aging is macroautophagy, which is regulated by numerous autophagy-related genes (ATGs). Old age is associated with some impairment in chaperone-mediated autophagy, whereas the effect of aging on the third lysosomal process, microautophagy, is unclear.

AGING CHANGES IN SPECIFIC TISSUES THAT PREDISPOSE TO DISEASE

Aging changes in some tissues increase susceptibility to age-related disease as a secondary or downstream phenomenon (Fig. 94e-3). In humans, this includes, but is not limited to, the immune system (leading to increased infections and autoimmunity), hepatic detoxification (leading to increased exposure to disease-inducing endobiotics and xenobiotics), the endocrine system (leading to hypogonadism and bone disease), and the vascular system (leading to segmental or global ischemic changes in many tissues).

Inflammaging and Immunosenescence Old age is associated with increased background levels of inflammation including blood measurements of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and cytokines such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). This has been termed inflammaging. T cells (particularly naïve T cells) are less numerous because of age-related atrophy of the thymus, whereas B cells overproduce autoantibodies, leading to the age-related increase in autoimmune diseases and gammopathies. Thus older people are generally considered to be immunocompromised and have reduced responses to infection (fever, leukocytosis) with increased mortality.

Detoxification and the Liver Old age is associated with impaired detoxification of various disease-causing endobiotics (e.g., lipoproteins) and xenobiotics (e.g., neurotoxins, carcinogens), leading to increased systemic exposure. In humans, the liver is the major organ for the clearance of such toxins. Hepatic clearance of many substrates is reduced in old age as a consequence of reduced hepatic blood flow, impaired hepatic microcirculation, and in some cases, reduced expression of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes. These changes in hepatic detoxification also increase the likelihood of increased blood levels of, and adverse reactions to, medications.

Endocrine System Hormonal changes with aging have been a focus of aging research for over a century, partly because of the erroneous belief that supplementation with sex hormones will delay aging and rejuvenate older people. There are age-related reductions in sex steroids secondary to hypogonadism and, in females, menopause. Age-related declines in growth hormone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) are well established, as is the increase in insulin levels and associated insulin resistance. These hormonal changes contribute to some features of aging such as sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which may be delayed by hormonal supplementation. However, adverse effects of long-term hormonal supplementation outweigh any potential beneficial effects on lifespan.

Vascular Changes There is a continuum from vascular aging through to atherosclerotic disease, present in many, but not all, older people. Vascular aging changes overlap with the early stages of hypertension and atherosclerosis, with increasing arterial stiffness and vascular resistance. This contributes to myocardial ischemia and strokes but also appears to be associated with geriatric conditions such as dementia, sarcopenia, and osteoporosis. In these conditions, impaired exchange between blood and tissues is a common pathogenic factor. For example, the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia is increased in patients with risk factors for vascular disease, and there is pathologic evidence for microvascular changes in postmortem studies of brains of people with established Alzheimer’s disease. Similarly, strong epidemiologic links have been found between osteoporosis and standard vascular risk factors, whereas there are significant age-associated changes in the microcirculation of osteoporotic bone. Sarcopenia might also be related to the effects of age on the muscle vasculature, which is altered in old age. The sinusoidal microcirculation of the liver becomes markedly altered during aging (pseudocapillarization), which influences hepatic uptake of lipoproteins and other substrates. In fact, it has often been overlooked that in his original exposition of the free radical theory of aging, Harman proposed that the primary target of oxidative stress was the vasculature and that many aging changes were secondary to impaired exchange across the damaged blood vessels.

GENETIC INFLUENCES ON AGING

There is variability in aging and lifespan in populations of genetically identical species such as mice that are housed in the same environment. Moreover, the heritability of lifespan in human twin studies is estimated to be only 25% (although there is stronger hereditary contribution to extreme longevity). These two observations indicate that the cause of aging is unlikely to lie only within the DNA code. On the other hand, genetic studies initially undertaken in the nematode worm C. elegans and, more recently, in models from yeast to mice have shown that manipulating genes can have profound effects on the rate of aging. Perhaps surprisingly, this can often be generated by variability in single genes, and for some genetic mechanisms, there is very strong evolutionary conservation.

Genetic Progeroid Syndromes There are a few very rare, genetic premature aging conditions that are called progeroid syndromes. These conditions recapitulate some, but not all, age-related diseases and senescent phenotypes. They are mostly caused by impairment of genome and nuclear maintenance. These syndromes include the following:

• Werner’s syndrome. This is an autosomal recessive condition caused by a mutation in the WRN gene. This gene codes for a RecQ helicase, which unwinds DNA for both repair and replication. It is typically diagnosed in teen years, and there is premature onset of atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, cancers, and diabetes, with death by age of 50 years.

• Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS). This usually occurs as a de novo, noninherited mutation in the lamin A gene (LMNA), leading to an abnormal protein called progerin. LMNA is required for the nuclear lamina, which provides structural support to the nucleus. There are marked development changes obvious in infancy with subsequent onset of atherosclerosis, kidney failure, and scleroderma-like features and death during the teen years.

• Cockayne syndrome. This includes a number of autosomal recessive disorders with features such as impaired neurologic growth, photosensitivity (xeroderma pigmentosa), and death during childhood years. These disorders are caused by mutations in the genes for DNA excision repair proteins, ERCC-6 and ERCC-8.

Gene Studies in Long-Lived Humans The main genes that have been consistently associated with increased longevity in human candidate gene studies are APOE and FOXO3A. ApoE is an apoprotein found in chylomicrons, whereas the ApoE4 isoform is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease, which might explain its association with reduced lifespan. FOXO3A is a transcription factor involved in the insulin/IGF-I pathway, and its homolog in C. elegans, daf16, has a substantial impact on aging in these nematodes. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of centenarians have confirmed the association of longevity with APOE. GWAS have been used to identify a range of other single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that might be associated with longevity including SNPs in the sirtuin genes and the progeroid syndrome genes, LMNA and WRN. Gene set analysis of GWAS studies has shown that both the insulin/IGF-I signaling pathway and the telomere maintenance pathway are associated with longevity.

Of particular interest are people with Laron-type dwarfism. These people have mutations in the growth hormone receptor, which causes severe growth hormone resistance. In mice, similar knockout of the growth hormone receptor (GHRKO mice, Methuselah mice) is associated with extremely long life. Therefore, subjects with Laron’s syndrome have been carefully studied, and it was found that they have very low rates of cancer and diabetes mellitus and, possibly, longer lives.

Nutrient-Sensing Pathways Many living things have evolved to respond to periods of nutritional shortage and famine by increasing cellular resilience and delaying reproduction until food supply becomes abundant once again. This increases the chances of reproductive success and survival of offspring. Lifelong food shortage, often termed caloric restriction (or dietary restriction) increases lifespan and delays aging in many animals, probably as a nonadaptive side effect of this famine response. Many of the genes and pathways that regulate the way that cells respond to nutritional undersupply have been identified, initially in yeast and C. elegans. In general, manipulation of these pathways (through genetic knockout or overexpression or pharmacologic agonists and antagonists) alters the aging benefits of caloric restriction and, in some cases, the lifespan of animals on normal diets. These pathways are all very influential cellular “switches” that control a wide range of key functions including protein translation, autophagy, mitochondrial function and bioenergetics, and the cellular metabolism of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. The discovery of these nutrient-sensing pathways has led to targets for pharmacologic extension of lifespan. The main nutrient-sensing pathways that influence aging and responses to caloric restriction include the following:

• SIRT1. The sirtuins are a class of histone deacetylases that inhibit gene expression. The key nutrient-sensing member of this class in mammals is SIRT1. The activity of SIRT1 is regulated by levels of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), which are increased when cellular energy stores are depleted. Important downstream targets include PGC1a and NRF2, which act on mitochondrial biogenesis.

• Target of rapamycin (TOR, or mTOR in mammals). mTOR is activated by branched-chain amino acids, providing a link to dietary protein intake. It is a complex that orchestrates two pathways (TORC1 and TORC2). Key downstream targets of mTOR of relevance to aging include the tuberous sclerosis protein (TSC) and 4EBP1, which influence protein production.

• 5′ Adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is activated by increased levels of AMP, which reflect cellular energy status.

• Insulin signaling and IGF-I/growth hormone. These two pathways are usually considered together because they are the same in lower animals and have diverged only in higher animals. Insulin responds to carbohydrate intake. An important downstream target for this pathway is a transcription factor called daf16 in worms and FOXO in mammals and the fruit fly.

Mitochondrial Genes Mitochondrial function is influenced by genes located both in the mitochondria (mtDNA) and the nucleus. mtDNA is considered to have a prokaryotic origin and is highly conserved across taxa. It forms a circular loop of 16,569 nucleotides in humans. Aging is associated with increased frequency of mutations in mtDNA as a consequence of its high exposure to oxygen-derived free radicals and relatively inefficient DNA repair machinery. Nuclear DNA encodes approximately 1000–1500 genes for mitochondrial function, including genes involved with oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial metabolic pathways, and enzymes required for biogenesis. These genes are thought to have originated in mtDNA but subsequently translocated to the nucleus, and unlike mtDNA genes, their sequence is stable with aging.

Genetic manipulation of mitochondrial genes in animals influences aging and lifespan. In C. elegans, many mutants with defective electron transfer chain function have increased lifespan. The mtDNA “mutator” mice, which lack the mtDNA proofreading enzyme, have increased mtDNA mutations and premature aging, whereas overexpression of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins leads to longer lifespan. In humans, hereditary variability in mtDNA is associated with diseases (mitochondriopathies such as Leigh’s disease) and aging. For example, in Europeans, mitochondrial DNA haplogroup J (haplogroups are combinations of genetic variants that exist in specific populations) is associated with longevity, and haplogroup D is overrepresented in Asian centenarians.

STRATEGIES THAT INCREASE HEALTHSPAN AND DELAY AGING

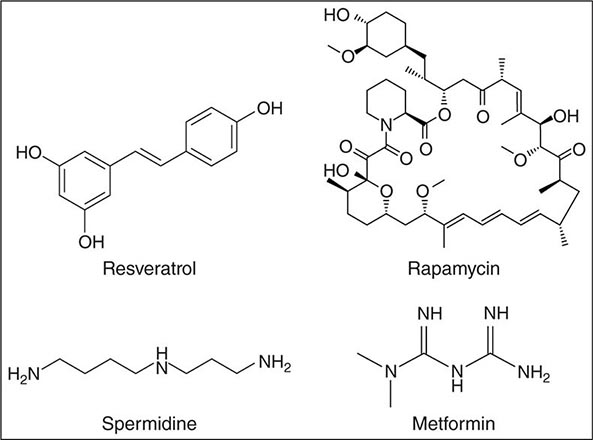

Aging is an intrinsic feature of human life whose manipulation has fascinated humans ever since becoming conscious of their own existence. Recent reports and scientific literature are shaping a picture where different dietary restriction regimes and exercise interventions may improve healthy aging in laboratory animals. Several long-term experimental interventions (e.g., resveratrol, rapamycin, spermidine, metformin) may open doors for corresponding pharmacologic strategies. Surprisingly, most of the effective aging interventions proposed converge on only a few molecular pathways: nutrient signaling, mitochondrial proteostasis, and the autophagic machinery.

Lifespan is inevitably accompanied by functional decline, a steady increase in a plethora of chronic diseases, and ultimately death. For millennia, it has been a dream of mankind to prolong both lifespan and healthspan. Developed countries have profited from the medical improvements and their transfer to public health care systems, as well as from better living conditions derived from their socioeconomic power, to achieve remarkable increases in life expectancy during the last century. In the United States, the percentage of the population age 65 years or older is projected to increase from 13% in 2010 to 19.3% in 2030. However, old age remains the main risk factor for major life-threatening disorders, and the number of people suffering from age-related diseases is anticipated to almost double over the next two decades. The prevalence of age-related pathologies represents a major threat as well as an economic burden that urgently needs effective interventions.

Molecules, drugs, and other interventions that might decelerate aging processes continue to raise interest among both the general public and scientists of all biologic and medical fields. Over the past two decades, this interest has taken root in the fact that many of the molecular mechanisms underlying aging are interconnected and linked with pathways that cause disease, including cancer and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Unfortunately, among the many proposed aging interventions, only a few have reached a certain age themselves. Results often lack reproducibility because of a simple inherent problem: interventions in aging research take a lifetime. Experiments lasting the lifetime of animal models are prone to develop artifacts, increasing the possibilities and time windows for experimental discrepancies. Some inconsistencies in the field arise from overinterpreting lifespan-shortening models and scenarios as being related to accelerated aging.

Many substances and interventions have been claimed to be antiaging throughout history and into the present. In the following sections, interventions will be restricted to those that meet the following highly selective criteria: (1) promotion of lifespan and/or healthspan, (2) validation in at least three model organisms, and (3) confirmation by at least three different laboratories. These interventions include (1) caloric restriction and fasting regimens, (2) some pharmacotherapies (resveratrol, rapamycin, spermidine, metformin), and (3) exercise.

Caloric Restriction One of the most important and robust interventions that delays aging is caloric restriction. This outcome has been recorded in rodents, dogs, worms, flies, yeasts, monkeys, and prokaryotes. Calorie restriction is defined as a reduction in the total caloric intake, usually of about 30% and without malnutrition. Caloric restriction reduces the release of growth factors such as growth hormone, insulin, and IGF-I, which are activated by nutrients and have been shown to accelerate aging and enhance the probability for mortality in many organisms. Yet the effects of caloric restriction on aging were first discovered by McCay in 1935 long before the effects of such hormones and growth factors on aging were recognized. The cellular pathways that mediate this remarkable response have been explored in many experimental models. These include the nutrient-sensing pathways (TOR, AMPK, insulin/IGF-I, sirtuins) and transcription factors (FOXO in D. melanogaster and daf16 in C. elegans). The transcription factor Nrf2 appears to confer most of the anticancer properties of caloric restriction in mice, even though it is dispensable for lifespan extension.

Two studies have reported the effects of caloric restriction in monkeys with different outcomes: one study observed prolonged life, while the other did not. However, both studies confirmed that caloric restriction increases healthspan by reducing the risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. In humans, caloric restriction is associated with increased lifespan and healthspan. This is most convincingly demonstrated in Okinawa, Japan, where one of the most long-lived human populations resides. In comparison to the rest of the Japanese population, Okinawan people usually combine an above-average amount of daily exercise with a below-average food intake. However, when Okinawan families move to Brazil, they adopt a Western lifestyle that affects both exercise and nutrition, causing a rise in weight and a reduction in life expectancy by nearly two decades. In the Biosphere II project, where volunteers lived together for 24 months undergoing an unforeseen severe caloric restriction, there were improvements in insulin, blood sugar, glycated hemoglobin, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure—all outcomes that would be expected to benefit lifespan. Caloric restriction changes many aspects of human aging that might influence lifespan such as the transcriptome, hormonal status (especially IGF-I and thyroid hormones), oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial function, glucose homeostasis, and cardiometabolic risk factors. Epigenetic modifications are an emerging target for caloric restriction.

It must be noted that maintaining caloric restriction and avoiding malnutrition is not only arduous in humans but is also linked with substantial side effects. For instance, prolonged reduction of calorie intake may decrease fertility and libido, impair wound healing, reduce the potential to combat infections, and lead to amenorrhea and osteoporosis.

Although extreme obesity (body mass index [BMI] >35) leads to a 29% increased risk of dying, people with BMI in the overweight range seem to have reduced mortality, at least in population studies of middle-aged and older subjects. People with a BMI in the overweight range seem more able to counteract and respond to disease, trauma, and infection, whereas caloric restriction impairs healing and immune responses. On the other hand, BMI is an insufficient denominator of body and body fat composition. A well-trained athlete may have a similar BMI as an overweight person because of the higher muscle mass density. The waist-to-hip ratio is a much better indicator for body fat and an excellent and stringent predictor of the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease: the lower the waist-to-hip ratio, the lower is the risk.

PERIODIC FASTING How can caloric restriction be translated to humans in a socially and medically feasible way? A whole series of periodic fasting regimens are asserting themselves as suitable strategies, among them the alternate-day fasting diet, the “five:two” intermittent fasting diet, and a 48-h fast once or twice each month. Periodic fasting is psychologically more viable, lacks some of the negative side effects, and is only accompanied by minimal weight loss.

It is striking that many cultures implement periodic fasting rituals, for example Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, and some African animistic religions. It could be speculated that a selective advantage of fasting versus nonfasting populations is conferred by health-promoting attributes of religious routines that periodically limit caloric intake. Indeed, several lines of evidence indicate that intermittent fasting regimens exert antiaging effects. For example improved morbidity and longevity were observed among Spanish home nursing residents who underwent alternate-day fasting. Even rats subjected to alternate-day fasting live up to 83% longer than normally fed control animals, and one 24-h fasting period every 4 days is sufficient to generate lifespan extension

Repeated fasting and eating cycles may circumvent the negative side effects of sustained caloric restriction. This strategy may even yield effects despite extreme overeating during the nonfasting periods. In a spectacular experiment, mice fed a high-fat diet in a time-restricted manner, i.e., with regular fasting breaks, showed reduced inflammation markers and no fatty liver and were slim in comparison to mice with equivalent total calorie consumption but ad libitum. From an evolutionary point of view, this kind of feeding pattern may reflect mammalian adaptation to food availability: overeating in times of nutrient availability (e.g., after a hunting success) and starvation in between. This is how some indigenous peoples who have avoided Western lifestyles live today; those who have been investigated show limited signs of age-induced diseases such as cancer, neurodegeneration, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension.

Fasting exerts beneficial effects on healthspan by minimizing the risk of developing age- related diseases including hypertension, neurodegeneration, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. The most effective and rapid repercussion of fasting is reduction in hypertension. Two weeks of water-only fasting resulted in a blood pressure below 120/80 mmHg in 82% of subjects with borderline hypertension. Ten days of fasting cured all hypertensive patients who had been taking antihypertensive medication previously.

Periodic fasting dampens the consequences of many age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and frontotemporal dementia, but not amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mouse models). Fasting cycles are as effective as chemotherapy against certain tumors in mice. In combination with chemotherapy, fasting protected mice against the negative side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs, while it enhanced their efficacy against tumors. Combining fasting and chemotherapy rendered 20–60% of mice cancer-free when inoculated with highly aggressive tumors like glioblastoma or pancreatic tumors, which have 100% mortality even with chemotherapy. This approach has been attempted in people with some indication that toxicities of chemotherapy are reduced.

Pharmacologic Interventions to Delay Aging and Increase Lifespan Virtually all obese people know that stable weight reduction will reduce their elevated risk of cardiometabolic disease and enhance their overall survival, yet only 20% of overweight individuals are able to lose 10% of their weight for a period of at least 1 year. Even in the most motivated people (such as the “Cronies” who deliberately attempt long-term caloric restriction in order to extend their lives), long-term caloric restriction is extremely difficult. Thus, focus has been directed at the possibility of developing medicines that replicate the beneficial effects of caloric restriction without the need for reducing food intake (“CR-mimetics,” Fig. 94e-5):

FIGURE 94e-5 Chemical structures of four agents (resveratrol, rapamycin, spermidine, and metformin) that have been shown to delay aging in experimental animal models.

• Resveratrol. Resveratrol, an agonist of SIRT1, is a polyphenol that is found in grapes and in red wine. The potential of resveratrol to promote lifespan was first identified in yeast, and it has gathered fame since, at least in part because it might be responsible for the so-called French paradox whereby wine reduces some of the cardiometabolic risks of a high-fat diet. Resveratrol has been reported to increase lifespan in many lower order species such as yeast, fruit flies, worms, and mice on high-fat diets. In monkeys fed a diet high in sugar and fat, resveratrol had beneficial outcomes related to inflammation and cardiometabolic parameters. Some studies in humans have also shown improvements in cardiometabolic function, whereas others have been negative. Gene expression studies in animals and humans reveal that resveratrol mimics some of the metabolic and gene expression changes of caloric restriction.

• Rapamycin. Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, was originally discovered on Easter Island (Rapa Nui; hence its name) as a bacterial secretion with antibiotic properties. Before its immersion in the antiaging field, rapamycin already had a longstanding career as an immunosuppressant and cancer chemotherapeutic in humans. Rapamycin extends lifespan in all organisms tested so far, including yeast, flies, worms, and mice. However, the potential utility of rapamycin for human lifespan extension is likely to be limited by adverse effects related to immunosuppression, wound healing, proteinuria, and hypercholesterolemia, among others. An alternative strategy may be intermittent rapamycin feeding, which was found to increase mouse lifespan.

• Spermidine. Spermidine is a physiologic polyamine that induces autophagy-mediated lifespan extension in yeast, flies, and worms. Spermidine levels decrease during the life of virtually all organisms including humans, with the stunning exception of centenarians. Oral administration of spermidine and upregulation of bacterial polyamine production in the gut both lead to lifespan extension in short-lived mouse models. Spermidine has also been found to have beneficial effects on neurodegeneration probably by increasing transcription of genes involved in autophagy.

• Metformin. Metformin, an activator of AMPK, is a biguanide first isolated from the French lilac that is widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metformin decreases hepatic gluconeogenesis and increases insulin sensitivity. Metformin has other actions including inhibition of mTOR and mitochondrial complex I and activation of the transcription factor SKN-1/Nrf2. Metformin increases lifespan in different mouse strains including female mouse strains predisposed to high incidence of mammary tumors. At a biochemical level, metformin supplementation is associated with reduced oxidative damage and inflammation and mimics some of the gene expression changes seen with caloric restriction.

Exercise and Physical Activity In humans and animals, regular exercise reduces the risk of morbidity and mortality. Given that cardiovascular diseases are the dominant cause of aging in humans but not in mice, the effects on human health may be even stronger than those seen in mouse experiments. An increase in aerobic exercise capacity, which declines during aging, is associated with favorable effects on blood pressure, lipids, glucose tolerance, bone density, and depression in older people. Likewise, exercise training protects against aging disorders such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis. Exercise is the only treatment that can prevent or even reverse sarcopenia (age-related muscle wasting). Even moderate or low levels of exercise (30 min walking per day) have significant protective effects in obese subjects. In older people, regular physical activity has been found to increase the duration of independent living.

While clearly promoting health and thus quality of life, regular exercise does not extend lifespan. Furthermore, the combination of exercise with caloric restriction has no additive effect on maximal lifespan in rodents. On the other hand, alternate-day fasting with exercise is more beneficial for the muscle mass than single treatments alone. In nonobese humans, exercise combined with caloric restriction has synergistic effects on insulin sensitivity and inflammation. From the evolutionary perspective, the responses to hunger and exercise are linked: when food is scarce, increased activity is required to hunt and gather.

Hormesis The term hormesis describes the, at first sight paradoxic, protective effects conferred by the exposure to low doses of stressors or toxins (or as Nietzsche stated, “What does not kill him makes him stronger”). Adaptive stress responses elicited by noxious agents (chemical, thermal, or radioactive) precondition an organism, rendering it resistant to subsequent higher and otherwise lethal doses of the same trigger. Hormetic stressors have been found to influence aging and lifespan, presumably by increasing cellular resilience to factors that might contribute to aging such as oxidative stress.

Yeast cells that have been exposed to low doses of oxidative stress exhibit a marked antistress response that inhibits death following exposure to lethal doses of oxidants. During ischemic preconditioning in humans, short periods of ischemia protect the brain and the heart against a more severe deprivation of oxygen and subsequent reperfusion-induced oxidative stress. Similarly, the lifelong and periodic exposure to various stressors can inhibit or retard the aging process. Consistent with this concept, heat or mild doses of oxidative stress can lead to lifespan extension in C. elegans. Caloric restriction can also be considered to be a type of hormetic stress that results in the activation of antistress transcription factors (Rim15, Gis1, and Msn2/Msn4 in yeast and FOXO in mammals) that enhance the expression of free radical–scavenging factors and heat shock proteins.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians need to understand aging biology in order to better manage people who are elderly now. Moreover there is an urgent need to develop strategies based on aging biology that delay aging, reduce or postpone the onset of age-related disorders, and increase functional life and healthspan for future generations. Interventions related to nutritional interventions and drugs that act on nutrient-sensing pathways are being developed and, in some cases, are already being studied in humans. Whether these interventions are universally effective or species/individual specific needs to be determined.