Chapter 20 The at-risk fetus

Most fetuses grow normally throughout pregnancy (see Fig. 6.13, p. 46). Some fetuses are genetically programmed to have a low growth potential. They are healthy, but small at birth. Some have a genetic defect which reduces their growth potential and causes slow intra-uterine growth, which may not become apparent until some time in the second half of pregnancy. Some fetuses grow normally initially, but in the last trimester of pregnancy their growth is restricted by alterations in uteroplacental function. This has led to the use of the descriptive term placental dysfunction or placental insufficiency.

Within genetically set limits, the actual fetal growth depends on:

With this background the identified causes of fetal growth restriction can be defined (Table 20.1). The degree to which these causes affect fetal growth depends on the amount of placental functioning reserve, and so not all women having these complications will give birth to a growth-restricted fetus.

Table 20.1 Aetiological factors in fetal growth restriction (placental dysfunction)

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Maternal causes | |

| Fetal causes | 10 |

| Unknown | 20 |

HIGH-RISK PREGNANCY

A second method of detecting fetal growth restriction is to measure the symphysiofundal height with a tape measure and refer to a chart (see Fig. 6.12, p. 46).

TESTS FOR FETAL WELLBEING IN HIGH-RISK PREGNANCIES

None of these has a high positive predictive value, but each has a high negative predictive value.

Cardiotocography – the non-stress test

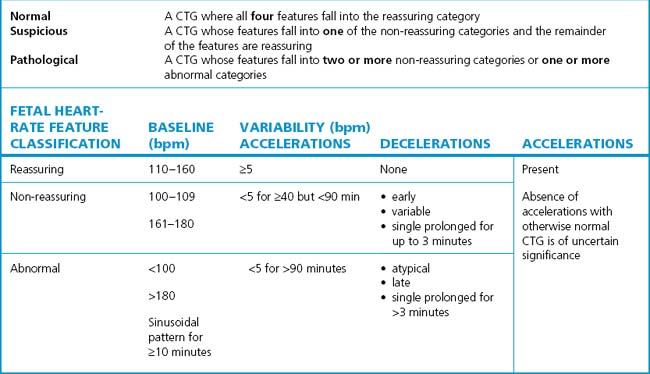

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ Cardiotograph Classification is shown in Table 20.2. There are three grades:

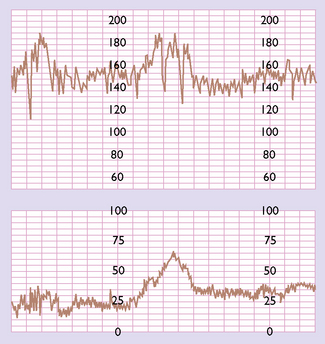

A normal pattern indicates that the fetus is not at risk of dying in the next 7–10 days (Fig. 20.1). Such a fetus is termed reactive. If a suboptimal pattern is found the fetus is at slightly increased risk and the test should be repeated in 3–4 days. The clinical management reaction to a suspicious or pathological CTG tracing will depend on the overall clinical picture and the gestational age of the fetus. A suspicious tracing merits closer surveillance and/or delivery if the fetus is at term, a pathological tracing intensive surveillance and, if persistent, consideration of delivery (frequently by caesarean section) if the fetus has reached viability (Fig. 20.2).

Serial ultrasound examinations

The growth of the fetus, as a measure of its health, may be monitored by examining it using real-time ultrasound at 3-weekly intervals. The fetal abdominal circumference, head circumference, femur length and estimated fetal weight are calculated and related to the centile chart for the sex of the fetus. In addition, the longest column of amniotic fluid is measured and the amniotic fluid index (AFI) calculated (see Ch. 19, p. 150–151). In some centres customized growth or centile charts are used which make adjustment for the mother’s parity, height, weight and ethnic origin. This approach has been shown to improve the accuracy of identification of growth-restricted fetuses and helps differentiate those fetuses from ones that are genetically small but developing normally.

Fetal blood flow velocity

Uteroplacental and fetoplacental circulations are low-resistance systems in which the flow of blood towards the placenta continues throughout the cardiac cycle, causing waveforms of different types. If fetoplacental vascular resistance increases because of acute uteroplacental atherosclerosis, fetal disease or unknown causes, the waveforms are altered. In the umbilical artery the difference between the peak systolic flow (S) and end-diastolic flow (D) can be measured (Fig. 20.3). The greater the S : D ratio the more likely it is that the fetus will be compromised, particularly if absent or reversed end-diastolic flow velocity (AEDFV) or extreme S : D ratio is found.

MANAGEMENT OF A HIGH-RISK PREGNANCY

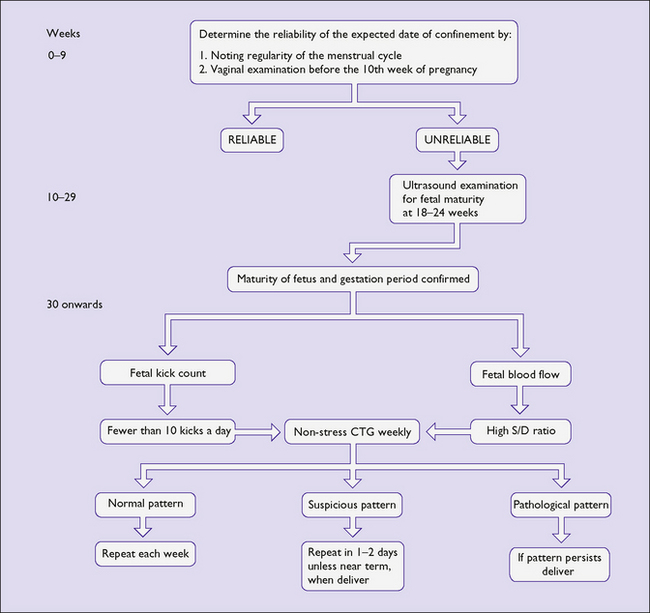

All that can be done is to monitor the maternal disease if it is present, to detect deterioration and to check fetal wellbeing (Fig. 20.4). If the maternal condition worsens, for example pre-eclampsia deteriorates or if the fetal monitoring becomes grossly abnormal, e.g. ominous CTG, persistent reverse end-diastolic blood flow, the pregnancy should be terminated either by inducing labour or by caesarean section. If the gestation is less than 34 weeks then if feasible the mother should be given corticosteroids before delivery to enhance fetal lung maturity.

MONITORING THE AT-RISK FETUS IN LABOUR

When caesarean section is not chosen to perform an immediate delivery, the health of the mother and fetus should be monitored during the labour. The care of the woman in labour is described in Chapter 8. In this section the care of the fetus will be described.

Fetuses which are at particular risk of developing hypoxia and acidaemia are those whose mother has had a pregnancy complication, or those who have been compromised either before labour or during the birth process (Box 20.1).

Box 20.1 Fetuses at high risk of developing intrapartum hypoxia and acidaemia

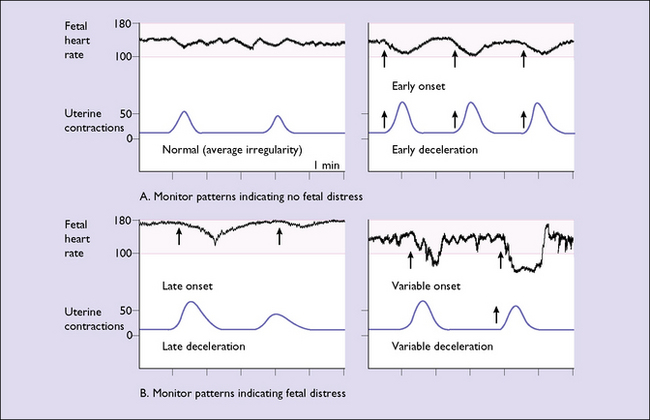

The fetal heart monitor records these changes in the fetal heart rate in relation to uterine contractions. The abnormal patterns are shown in Figure 20.5: