Chapter 13 The assessment and care of musculoskeletal problems

Introduction

Musculoskeletal problems account for an estimated 3.5 million Emergency Department (ED) attendances each year. More patients will consult their general practitioner (GP) or treat the problem themselves. The majority of these conditions (sprains, bruises and aches) will be self-limiting, requiring clinical diagnosis, and straightforward treatment and advice.

However, there are diagnostic dilemmas facing the practitioner on the ‘front line’. Even simple injuries often need hospital assessment, usually for X-rays. Some problems are rare but important to diagnose if life- or limb-threatening problems are to be avoided. The skill is to recognise those conditions where urgent referral and treatment are required. The aim of this chapter is to arm the practitioner with these skills (Box 13.1). Major trauma is not covered here.

The primary survey

Patients with a normal primary survey but obvious need for hospital attendance

Certain conditions pose a serious threat to life or limb and must not be missed when considering a ‘wait-and-see’ approach. The conditions listed in Box 13.2 are the ‘red flag’ conditions of the musculoskeletal system.

A major joint dislocation should be reduced as soon as possible, particularly if there is no distal circulation or sensation to the limb. Acutely ischaemic limbs need to have circulation restored within 4 hours to prevent irreversible muscle and nerve damage. Therefore make one gentle effort at relocation. Otherwise the limb needs to be splinted in its current position and urgent transfer arranged.

Secondary survey patients

Assessment of the stable patient

The assessment is carried out according to the recognised system (SOAPC) outlined in Chapter 2. The first step is to decide if the problem is due to trauma or one of the many causes of non-traumatic limb or spinal pain. The spectrum of diagnoses is very different in these two groups.

Trauma vs no history of trauma

Patients who present with no history of trauma should alert the clinician to the possibility of missing Referred pain, Ischaemic syndromes, Sepsis and Kids problems such as epiphyseal abnormalities. Remember the mnemonic RISK. These are the conditions commonly overlooked and can indicate limb- or even life-threatening problems such as cardiac pain, a slipped upper femoral epiphysis or a septic joint.

Subjective information gathering – the history

Definite trauma

Acute trauma is caused by a single, clear event. This can lead to a wide spectrum of injury from minor self-limiting sprains to fractures and/or dislocations of joints. The features of a fracture are pain, swelling, loss of function and bony tenderness. Dislocations are usually more obvious with similar features to fractures plus an abnormal joint morphology with deformity. In the absence of these features then a soft tissue injury is more likely but consider damage to other structures such as ligaments, tendons, nerves and vessels (Box 13.3).

Mechanism of injury

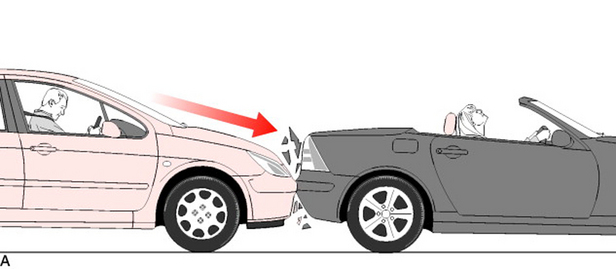

A clear history of the mechanism of injury is essential to accurate diagnosis in trauma. Elicit the magnitude and direction of the forces causing the injury. Simple errors are made by a failure to follow this advice. For example, if the only history obtained was ‘hurt neck in road traffic accident’ the clinician might jump to the conclusion the injury was likely to be a simple neck sprain. However, consider how different your actions might be if a full history were to be obtained such as ‘hurt neck in road traffic accident, was unrestrained front seat passenger in car which overturned at speed’ (Fig. 13.1).

Symptoms and progress

Pain, swelling and loss of function are the main symptoms following injury. Ask if these symptoms have progressed since the incident. A sudden and complete loss of function at time of impact increases the risk for a more severe injury. Ask about associated symptoms such as paraesthesia and trauma elsewhere.

Level of activity

Patient expectations are an important consideration in the management of musculoskeletal injuries. A professional athlete will demand as near 100% function as is possible post-injury but most patients will manage very well with minor ligament instability as long as they have good protective neuromuscular function. Nevertheless it is important to consider occupation, hobbies and handedness so that expectations and needs can be identified.

No definite trauma

Patients who present with a limb or spinal pain but with no history of trauma can present diagnostic problems. In the majority of patients the illness will be minor and self-limiting or of a chronic nature not needing urgent treatment or investigation. However a minority of patients with these ‘minor’ symptoms may be suffering from life- or limb-threatening pathology. The mnemonic ‘RISK’ highlights the categories of serious diagnoses that may require exclusion (Box 13.4). Always consider the RISK diagnoses – failure to do so will lead to them being missed.

The ‘OPQRST’ of pain

O – Onset

A very sudden onset of pain is often associated with a vascular problem such as occlusion or referred pain from cardiac ischaemia or a leaking aortic aneurysm. Sudden pain waking the patient at night is a worrying symptom. Some mechanical problems do cause a sudden onset of pain in the absence of definite trauma, examples include an acute intervertebral disc prolapse or a loose body in a joint. Many other causes of limb pain will cause a gradual onset or intermittent symptoms.

Objective information gathering – the examination

Develop a systematic method of musculoskeletal examination:

See Chapter 2 on examination, including the musculoskeletal system. See also Wardrope,2 Cyriax5 and McRae6 for a fuller examination description of anatomical regions

Where there is no history of trauma, follow the same system but check vital signs and look for other clinical signs as summarised in Box 13.6.

Objective information – tests

X-Rays – indications

Use local guidelines and policy to decide when an X-ray is indicated. The definite fractures are easy to diagnose but unfortunately many fractures are undisplaced and it is difficult to confidently exclude a fracture without an X-ray. Many experienced clinicians would advise ‘X-ray when in doubt’. Other indications include suspected foreign body within a wound, e.g. glass or metal. For further information see the Royal College of Radiologists guidance on www.rcr.ac.uk and ‘Making the best use of a Department of Clinical Radiology’.7

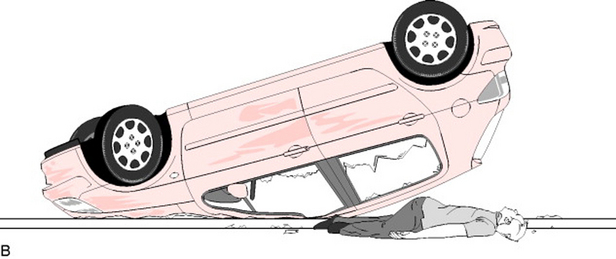

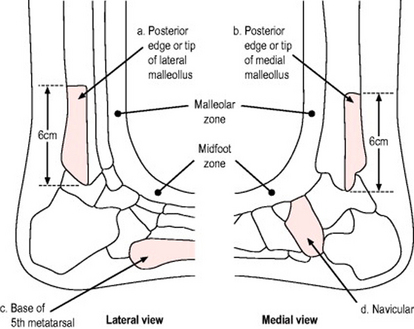

There are other excellent reference sources available for the need to X-ray certain anatomical areas such as the ankle. Probably the best known are the Ottawa ankle rules8 used to help decision making in the assessment of acute ankle injuries that may either be sprained (the majority) or fractured (Fig. 13.2).

Other decision rules exist for similar use in acute knee9 and neck10 injuries.

In January 2000 the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposures) Regulations came into force to protect patients undergoing exposure to X-rays. Any clinician ordering X-rays independently needs to be accredited and attend training on this subject. For further information on IRMER legislation see the Department of Health website (www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/05/78/38/04057838.pdf).

Investigations – no definite trauma

Many patients will not require any immediate investigation and may be referred to their GP for further assessment. However if you suspect any of the RISK diagnoses, investigations such as blood tests, examination of joint fluid, ultrasound, bone scans and CT or MRI scanning may be required. In addition, X-rays of the area may be required – but note that many serious conditions may have an initially normal X-ray.

Analysis and differential diagnosis

Trauma

No definite trauma

Consider referred pain, ischaemia, sepsis and kids (RISK) as causes of pain when no other cause seems apparent. Limb pain could be due to a septic joint, a critical ischaemia or referred from spine, abdomen or chest.

Consider referred pain, ischaemia, sepsis and kids (RISK) as causes of pain when no other cause seems apparent. Limb pain could be due to a septic joint, a critical ischaemia or referred from spine, abdomen or chest.Specific problems

Back pain

One very common problem is acute mechanical back pain, this usually occurs in young fit people. The pain usually starts suddenly and is often severe. However, if there are no ‘red flag’ symptoms (Box 13.7), advice is given to try to stay mobile and good analgesia prescribed. Cases with unusual or continuing severe symptoms should be reviewed early by their GP.

Pain radiating down the back of the leg to below the knee may indicate sciatic nerve irritation. A careful neurological examination is needed. Refer for early review by the GP.11 If there is pain down both legs or any disturbance of motor power, bladder or bowel function, then refer to hospital immediately.

Box 13.7 shows ‘red flags’ that might indicate serious spinal pathology in back pain (adapted from the Report of Clinical Standards Advisory Group on Back Pain11).

Neck pain

Causes include whiplash injury, torticollis, referred pain, degenerative disease and infection. As with back pain, a good history of trauma will allow an assessment of the neck for injury such as fracture dislocation. Guidance on how to ‘clear the C-spine’ after trauma has been issued by NICE12 and Stiell10 and is summarised by Wardrope13 (Box 13.8).

Degenerative disease/osteoarthritis

These chronic progressive conditions can affect any region of the body, but most commonly are encountered in the hip, knee and cervical and lumbar spine. They may present as a new problem, an acute flare up of the chronic condition after relatively minor trauma, or as a more significant injury or infection superimposed on coincidental findings of degenerative disease.

The acutely hot/swollen/painful joint

The commonest problems causing an acutely swollen, hot joint are the crystal arthropathies of gout and pseudogout and acute inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. Sepsis is relatively rare but is a diagnosis not to be missed. Acute haemarthrosis is uncommon without a history of trauma, coagulopathy or anticoagulant treatment.

Degenerative disease such as osteoarthritis often causes joint swelling but the joint is not usually hot and red (Box 13.9).

The diagnoses not to miss are osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. Septic arthritis can arise de novo or from spread from an area of osteomyelitis into the joint. They both present in a similar way. There is either no history of trauma or a history of insignificant trauma for the degree of pain. There may be a history of joint penetration, either in an accident or caused by a medical intervention. The patient cannot move the joint at all and strongly resists any passive movements. Early in the course of these illnesses, all these classical findings may not be present. Consider sepsis a possibility in any acute joint problem and arrange for early review. If in doubt refer for a further opinion to the patient’s GP, rheumatology or A&E.

1 American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. ATLS manual, 6th edn. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1997.

2 Wardrope J, English B. Musculoskeletal problems in emergency medicine, 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

3 Apley AG, Solomon L. Apley’s system of orthopaedics and fractures, 7th edn. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995.

4 McRae R. Practical fracture management, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

5 Cyriax JH, Cyriax PJ. Cyriax’s illustrated manual of orthopaedic medicine, 2nd edn. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

6 McRae R. Clinical orthopaedic examination. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

7 Royal College of Radiologists. Making the best use of a department of clinical radiology. Guidelines for doctors, 5th edn. RCR, London, 2003.

8 Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, Nair RC, McDowell I, Worthington JR. A study to develop clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:384-390.

9 Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, Wells GA, et al. Prospective validation of a decision rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA. 1996;275(8):611-615.

10 Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1841-1848.

11 Clinical Standards Advisory Group. Report of the Clinical Standards Advisory Group on Back Pain. London: HMSO, 1994.

12 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. In Clinical Practice Algorithm No. 4. London: NICE; 2003.

13 Wardrope J, Ravichandran G, Locker T. Risk assessment for spinal injury after trauma. BMJ. 2004;328:721-723.