Chapter 14 The Arthritides

Disorders of the joints are common and may cause considerable pain and disability. They are frequently classified as noninflammatory, inflammatory, or infectious. This chapter reviews the more common joint affections.

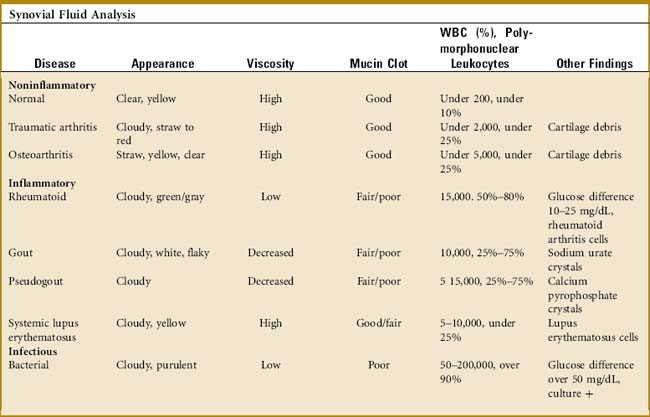

The Synovium

A great deal of information can be obtained from the examination of a joint aspirate (Table 14-1). However, this examination is not indicated in every joint effusion and should be limited to those diagnostic problems that are not secondary to trauma. (Usually, the two disorders of most concern are infection and crystalline arthritis.) The joint is usually aspirated from the extensor side under sterile conditions. Three test tubes are sufficient for most determinations: (1) a plain tube for gross examination, clotting, and a mucin clot test; (2) one ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid–treated tube for cell and crystal analysis; and (3) one heparinized tube for bacteriologic study. Five milliliters of fluid are placed in each tube.

THE MUCIN CLOT TEST

This test determines the amount of hyaluronate in the fluid. Acetic acid is added to the tube, and the sample is observed for clot formation. A “poor” mucin clot indicates a decrease in hyaluronate. This results from dilution, depolymerization, and loss of filter function from either inflammation or infection. A “good” clot is present in normal fluid and osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis

CLINICAL FEATURES

Pain is the most common initial symptom. This frequently occurs with motion or activity and is relieved by rest. The source of discomfort is unknown. It may result from chemical mediators and possibly mechanical factors. Joint stiffness typically occurs with rest and improves with activity. The physical findings include crepitus, joint line tenderness, swelling, restriction of motion, and joint enlargement from osteophyte formation. In the hands, these osteophytic overgrowths are termed Heberden’s nodes when they are present at the distal interphalangeal joint and Bouchard’s nodes when they occur at the proximal interphalangeal joint. Pain is usually present on joint motion. Disuse atrophy of the adjacent musculature may develop rapidly, thus increasing the disability and pain. Even though osteoarthritis is not considered an “inflammatory” disease, mild increased temperature with palpable heat is often present. This can be appreciated clinically in a superficial joint (such as the knee) by placing one hand on the front of each knee of the sitting patient and then switching the hands back and forth. Subtle differences in temperature suggestive of synovitis (which indicates an intraarticular problem) may become more apparent. This clinical test is often helpful in the obese patient in whom an effusion may be difficult to visualize.

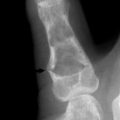

The roentgenographic findings consist of joint space narrowing, spur formation, sclerosis, and subchondral cyst formation (Fig. 14-1). The laboratory findings and synovial analysis are normal, except for occasional flakes of cartilage in the joint fluid. In most cases, a routine physical examination and plain films are sufficient to establish the diagnosis. More extensive radiographic testing is usually not indicated except in those cases in which the diagnosis is uncertain.

TREATMENT

Stretching exercises are helpful, and the joint should be passed through a full range of motion several times daily to reduce joint stiffness. The local application of moist heat often relieves discomfort during the acute painful stage and may be especially helpful before exercise. Exercises designed to combat stiffness and restore muscle strength are important, because the weakness contributes to joint instability and disability. The patient may benefit from a short course of formal physical therapy to develop a good home exercise program. All exercise should be low impact. Aquatic exercise programs are generally well tolerated. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are traditionally used for osteoarthritis, but may be no more effective than acetominophen for pain relief because the role of inflammation in the condition is uncertain. Mild analgesics may even be indicated on an occasional basis. Intraarticular cortisone injections are often very effective for pain relief. Their effect is usually only temporary, but the benefit may last several months. The injections can be repeated several times per year. Any recommended limits to the number of injections a patient may have per year appears to be arbitrary, although most patients seem to do well with three or four injections per year. Various liniments may be used for their counterirritant effect. Viscosupplementation (a series of joint injections using a hyaluronate-like material) has been tried, but the results are inconclusive. The efficacy of supplements such as chondroitin and glucosamine has not been well proven.

Orthopedic referral is indicated when there is no response to medical management. The most common surgical procedures are arthrodesis and arthroplasty (Fig. 14-2). Each is effective in eliminating the painful articulation. Realignment of faulty weight-bearing joints by osteotomy may also be beneficial.

GOUT

CLINICAL FEATURES

The initial acute attack is usually of sudden onset and occurs in a single joint or area of tenosynovium of the lower extremity (Table 14-2). The metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint of the great toe is classically the first site of involvement (podagra), although any joint or area of tenosynovium can be involved. The extensor synovium on the dorsum of the midfoot is another common site of acute attack, as is the knee joint (gonagra). In 80% to 90% of cases, the lower extremity is involved. The older patient with gout is more likely to have involvement of the fingers and to develop tophi. Older women may present with polyarticular disease, often involving atypical locations. The pain and inflammation are usually severe and may be precipitated by exercise, dietary indiscretion, and physical or emotional stress. Attacks are common after illness or shortly after surgery, and they typically begin at night. Swelling, heat, redness, and other signs of inflammation are usually present. The physical findings may even simulate cellulitis or infectious arthritis. The area is often tender to even the slightest touch. Fever, tachycardia, and other constitutional symptoms may accompany the attack. The initial episode may be followed later by polyarticular involvement. Eventually, deposits of urate crystals, termed tophi, may form in the subcutaneous tissue.

| Disorder | Symptoms/History | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Pyogenic arthritis | Usually painful but sometimes low grade. Fever, acute onset. Usually monoarticular. | Febrile, increased heat, painful movement. Systemic signs of illness. Joint fluid positive for bacteria. |

| Gouty arthritis | Knee, great toe, or generalized foot pain. Symptoms may be initiated by physical stress such as surgery. May be extremely painful but usually low grade. Usually monoarticular. Previous episodes? | Redness, increased heat. Crystals in joint fluid. Elevated serum uric acid. Fluid often cloudy. |

| Osteoarthritis | Chronic, gradual. Monoarticular. May have history of mechanical injury. Stiffness after rest, pain after prolonged activity | Restricted movement but pain usually only at the extremes of movement. Fluid is clear, only excessive amounts. |

| Pseudogout | Middle age to elderly. Usually monoarticular. Previous episodes? | Crystals in cloudy fluid (calcium pyrophosphate). |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Multiple joints may be involved. Females most commonly affected. Usually subacute or insidous in onset but occasionally acute. Often symmetric. Metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal joints usually involved. | Subcutaneous nodules in late cases. Laboratory studies may show positive rheumatoid test and increased ESR. |

| Others | History may reflect skin rash or other skin changes. Note other system involvement (complete history, especially GI, and pulmonary system). | FANA, ESR may be abnormal. Many collagen disorders have polyarticular symptoms and act like rheumatoid arthritis. |

ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FANA, flurorescent antinuclear antibody; GI, gastrointestinal.

* NOTES: The workup should include aspiration of joint fluid. Fluid is observed for color, and the string test is performed. The fluid is analyzed for cell count, Gram stain, crystal analysis, and culture and sensitivity. The blood work should include complete blood cell count, uric acid, blood cultures if indicated, sedimentation rate, fluorescent antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor. Blood cultures should include aerobic and anaerobic cultures. Roentgenographic evaluation is always performed to evaluate for osteoarthritis and calcific changes in soft tissues.

Early in the disease, roentgenogram findings are normal. Later, erosive changes appear that have a characteristic punched-out appearance (Fig. 14-3). Destruction and degeneration of the articular cartilage frequently follow.

The standard for the definitive diagnosis of gout requires crystal identification on joint aspirate, although a presumptive diagnosis is often established on clinical grounds, especially if associated with hyperuricemia. Laboratory findings include a mild leukocytosis, elevated sedimentation rate, and hyperuricemia, although acute attacks are occasionally associated with a normal level of uric acid. In some patients, the SUA level may decrease into the normal range during an acute attack. Uric acid levels are best checked again after the attack is over. The synovial aspirate is usually cloudy and mildly inflammatory in nature. Because acute gout and infectious arthritis can present identically, the fluid should also be tested for infection. Urate crystals are usually demonstrable. They are needle shaped and negatively birefringent (shine brightly) under polarized light. A 24-hour urinary collection for uric acid may be helpful in determining the appropriate treatment.

TREATMENT

The treatment of gout depends on the stage of the disease. The objectives in management are to terminate or prevent the acute attack, encourage mobilization of tophaceous deposits, and reduce the level of SUA.

Surgery is usually limited to excision of large tophi and, occasionally, arthroplasty.

Pseudogout (Chondrocalcinosis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical presentation is variable, but the symptoms are similar to those of chronic gouty arthritis. The age of onset is 60 to 70 years. Intermittent acute episodes occur, but the joint most commonly involved is the knee rather than the great toe. The attacks are usually monoarticular. The condition is frequently familial and is occasionally associated with diabetes, renal disease, and other systemic conditions. Like gout, acute attacks may be triggered by a variety of surgical or medical events. In addition to the goutlike symptoms, calcification of the cartilage of the knee, especially the meniscus, is common (Fig. 14-4). Calcification of the anulus fibrosus, radioulnar disc, and symphysis pubis may also be seen. Stippled calcification in bands running parallel to the subchondral bone margins may be present. Synovial fluid analysis reveals typical rhomboid-shape crystals that exhibit weakly positive birefringence under polarized light. There are no specific changes in blood or urine. The American Rheumatism Association criteria are often used for diagnosis:

Rheumatoid Arthritis

The etiology of the disorder is unknown, although it is most likely an immune response to some antigen, possibly viral. The result is the activation, by some unknown mechanism, of proinflammatory cells that infiltrate the synovium. These cells, in turn, release various substances such as cytokines and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which subsequently cause the pathologic changes typical to this group of diseases. Pathologically, the synovium becomes thickened, inflamed, and hypertrophic. An aggressive, infiltrating granulation tissue from the synovium (pannus) typically spreads over the joint cartilage. Eventually, erosion and destruction of the articular surface result from the chronic inflammatory process.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual although acute cases may occur. Weakness, fatigue, and anorexia are common prodromal symptoms. Eventually, joint involvement becomes apparent, with stiffness, swelling, heat, and redness. Stiffness is most pronounced in the morning because of the “gelling” effect of the excess fluid. Most cases initially present with multiple symmetric joint involvement, most often in the hands and feet (Table 14-3). The MCP, metatarsophalangeal (MTP), and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are usually involved, but the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are not. Eventually, most of the major joints become involved as well. Remissions and exacerbations are common, but the condition is chronically progressive in the majority of cases. The disease shortens life expectancy from 10 to 15 years.

Table 14-3 American Rheumatology Revised Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis (American College of Rheumatology)

| Rheumatoid arthritis is said to exist when four of the following seven conditions are present: |

| (Criteria 1–4 must be present for at least 6 weeks.) |

The roentgenogram usually reveals soft tissue swelling and osteoporosis early in the disease. Eventually, joint space narrowing, erosion, and deformity become visible as the result of continued inflammation and cartilage destruction (Fig. 14-5).

TREATMENT

Proper management requires close cooperation among primary physician, therapist, rheumatologist, and orthopedist. Early referral to a rheumatologist is especially important because evidence exists that outcomes are improved with early, aggressive medical management. The goals are to maintain function and to halt the irreversible damage that may become visible radiographically. Patient education is of utmost importance. (Information from the physician can be supplemented from outside sources, such as the Arthritis Foundation.) Rest is beneficial in reducing inflammation. When combined with an exercise program, moist heat, and splinting, joint deformities can frequently be prevented or corrected.

JUVENILE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (STILL’S DISEASE)

CLINICAL FEATURES

The roentgenographic findings in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis are the same as those in the adult, except that joint destruction is less frequent (Fig. 14-6). The laboratory findings are also similar, except that the peripheral WBC count may be very high and the rheumatoid factor is rarely demonstrable in the serum of children.

Neuroarthropathy

CLINICAL FEATURES

The foot is usually involved in diabetes, the shoulder and elbow joint in syringomyelia, and the vertebrae and lower extremities in tabes dorsalis (Fig. 14-7). Gradual enlargement and instability of the affected joint are common complaints. Pain is usually present but tends to be relatively mild when compared with the severity of the joint destruction.

The examination is characterized by swelling and hypermobility. Palpation frequently reveals gross deformity of bone and joint and crepitus. Early involvement of the foot because of diabetes is first manifest by painless swelling at the apex of the arch. As weight bearing continues, there is collapse of the arch with frank dislocation and deformity of the mid-foot. Eventually, the arch completely disintegrates, and a reverse arch or rockerbottom foot is formed (Fig. 14-8). There is commonly skin breakdown and ulcer formation where the dislocation has occurred.

Variable degrees of joint destruction and disintegration with exuberant osteophyte formation are usually present on roentgenographic examination. Later, subluxation and deformity may be seen (Fig. 14-9).

TREATMENT

Once the full-blown neuropathic joint has developed, treatment can be difficult. In the lower extremity, effu sions, sprains, and fractures should be well protected until all hyperemic response has subsided. Braces, special shoes with molded inserts, and elevation of the extremity are helpful. A “rockerbottom” shoe allows an improved walking pattern. Surgery is generally limited to debridement of bony prominences and local ulcer care.

Ochronosis

Alkaptonuria is an uncommon inherited disorder that results from a failure to properly synthesize homogentisic acid oxidase. Homogentisic acid is thus excreted in the urine, which causes it to turn black on oxidation. Ochronosis is the result of alkaptonuria and is characterized by the deposition in the soft tissue and cartilage of a pigment derived from homogentisic acid. The arthropathy of ochronosis primarily involves the spine, hips, knees, and shoulders. Typical calcifications appear in the intervertebral discs and menisci, although the substance that composes the pigment is either homogentistc or some derivative. Eventually, the peripheral joint changes become indistinguishable from osteoarthritis, and the spine involvement resembles ankylosing spondylitis (see Chapter 8). The excessive homogentisic acid does not result in any metabolic or nutritional symptoms. The arthropathy is the major manifestation of the disorder. Nearly all patients with the condition develop arthritis, mainly involving the major weight-bearing joints. There is only a minimal inflammatory component, the disease being primarily one of accelerated wear, possibly caused by some enzymatic problem that weakens the articular cartilage.

Reiter’s Syndrome

This is a disorder of unknown etiology characterized by urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis. It is one of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (see Chapter 8). Many enteric and sexually acquired agents appear capable of inducing the disorder, including Chlamydia and Shigella. It is also commonly called reactive arthritis. This term denotes a sterile arthritis, which develops in a joint as a result of an infection at a site distant from the inflamed joint itself.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriasis may occasionally be accompanied by a form of arthritis that is clinically similar to adult rheumatoid arthritis. Like Reiter’s syndrome, it is one of the seronegative splondyloarthropathies (see Chapter 8). The skin disorder usually precedes the arthritis by several years. There is often a strong family history of psoriasis.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

This is a very common disorder of unknown cause affecting older adults. It is characterized by chronic inflammation that causes stiffness and aching of the shoulder and hip regions. It is sometimes called “anarthritic rheumatoid syndrome.” The diagnosis is often difficult to make because there are no uniform diagnostic criteria for the disorder. There is a strong relationship of polymyalgia rheumatica to temporal (giant cell) arteritis, the two disorders being perhaps different phases of the same disease process.

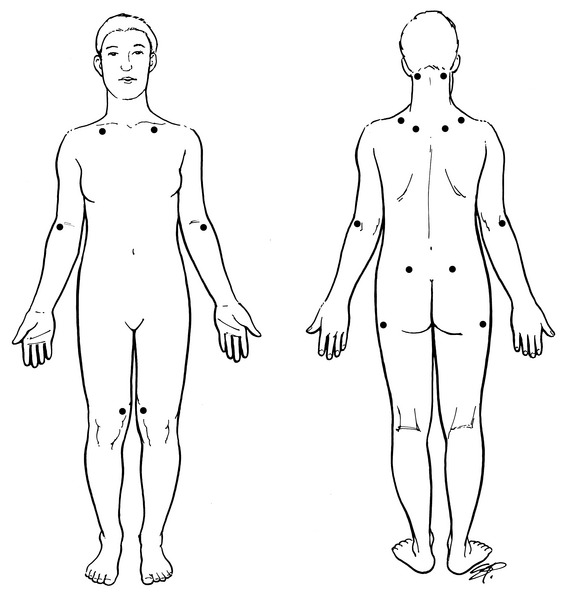

Fibromyalgia

This is a controversial clinical syndrome characterized by multiple trigger points and chronic (more than 3 months) diffuse pain (Fig. 14-10). Similar disorders have been called fibrositis, myofascial pain syndrome, and psychogenic rheumatism. The disorder is common, affecting as 2% to 3% of the general population.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Subsets of this disorder are often described if symptoms develop in conjunction with other conditions or after motor vehicle accidents, but the primary disorder is often suggested by the following criteria from the American College of Rheumatology:

TREATMENT

Education and self-management are important. Social and environmental factors may need to be addressed, especially stress and pending litigation. Simply establishing a diagnosis (giving it a name) can be helpful to the patient to learn that the condition is not progressive or fatal. A compassionate and reassuring approach is important. Support groups are also beneficial. The prognosis is uncertain. Symptoms may come and go for years, despite an aggressive, multifaceted approach to treatment.

Lyme Arthritis

TREATMENT

Antibiotics (usually penicillin or tetracycline) given for the disease can prevent the chronic arthritis. Even after the arthritis is established, antibiotic therapy (for 4 weeks) may be curative. In cases of “refractory” arthritis, IV antibiotics may be indicated. Children rarely have any long-term joint complications, and even in adults, the arthritis usually resolves without any significant destruction. NSAIDs are useful for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects. Intraarticular steroids can provide excellent symptomatic relief and do not appear to cause any adverse local effects. Chronic cases may require synovectomy.

Antiinflammatory Medication

Salicylates are effective, inexpensive, and generally well tolerated. If stomach intolerance is a problem, enteric-coated or buffered products are available that may lessen the gastric distress. One minor disadvantage of aspirin as compared with other NSAIDs is the frequent dosing regimen, although most of the prescription salicylates have more convenient dosing schedules. If salicylates or other over-the-counter medications are ineffective, inconvenient, or not well tolerated, a number of prescription drugs may be tried (Table 14-4). None of these seems clearly superior to the others, and as a general class, NSAIDs are thought by some investigators to be no better than even simple analgesics, at least in the treatment of osteoarthritis for which they are commonly recommended. (If only the analgesic effect is needed, plain acetaminophen may be better because of its safety profile, especially for osteoarthritis, in which inflammation plays less of a role.) These drugs are categorized into several classes, and when switching from one to another, it is best to select from a different class. Patients must also be reminded that all of these drugs are most effective for chronic pain when taken routinely. Although some therapeutic effect of these drugs usually begins in a few hours, the maximum benefit may require 1 to 2 weeks. However, if the pain is mild, some are effective taken as simple analgesics on an “as needed” basis. It is important to remember that prescription NSAIDs are expensive and should not be used casually. Also, combining one NSAID with another should not be done.

| NSAID | Usual Dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Salicylates | ||

| Acetylated | ||

| Aspirin | 3000 mg/day | Give in divided doses after food consumption |

| Non-acetylated | ||

| Dilflunisal (Dolobid) | 500 mg BID | May cause marrow depression |

| Choline magnesium trisalicylate (Trilisate), salicylsalicylic acid (Disalcid, Mono-Gesic) | 3000 mg/day | Less toxic, less effective? |

| Acetic acids | These may cause the most serious CNS side effects, which may limit their use (headache, depression, etc.) | |

| Sulindac (Clinoril) | 150–200 mg BID | |

| Indomethacin (Indocin) | 25–50 mg BID | Available in TR capsule; worst SE profile |

| Tolmetin (Tolectin) | 600 mg TID | |

| Diclofenac (Voltaren) | 50 mg TID | Available in SR form |

| Proprionic acids | Use carefully in patients with renal dysfunction. | |

| Ibuprofen (Motrin, etc.) | 600–800 mg TID | |

| Fenoprofen (Nalfon) | 600 mg TID | |

| Ketoprofen (Orudis) | 75 mg TID | |

| Flurbiprofen (Ansaid) | 100 mg BID | |

| Naproxen (Naprosyn) | 500 mg BID | Available over the counter and in SR form |

| Oxaprozin (Daypro) | 1200 mg/d | Once daily dosing |

| Others | ||

| Meloxicam (Mobic) | 7.5–15 mg/d | Can take without regard to food |

| Etodolac (Lodine) | 400 mg BID | |

| Nabumetone (Relafen) | 500 mg BID | Less GI toxicity |

| Piroxicam (Feldene) | 10–20 mg/day | Occasional photosensitivity |

| Meclofenamate (Meclomen) | 100 mg TID | Less hepatoxic; diarrhea common |

* Diclofenac and sulindac have the greatest potential for hepatotoxicity. Proprionic acids occasionally can cause photosensitivity. The following side effects are common to most NSAIDs: (1) gastric irritation, (2) interference with platelet function, (3) salt and water retention, and (4) visual disturbances. These drugs should not be used in combination. When changing drugs, change from one class to a separate class. Aspirin, the most commonly used NSAID, is also available under the trade name of Zorprin. This drug is released in the small intestine rather than the stomach. The usual dose is two 800-mg tablets twice a day.

NOTE: Most of the popular NSAIDs are becoming available in SR forms, often with less GI toxicity. Celocoxib, the COX-2 inhibitor, is usually prescribed in doses of 100–200 mg once or twice each day.

CNS, Central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; SE, side effects; SR, sustained release; TR, time-release.

USES

The benefits of this class of drugs to patients with inflammatory joint diseases are enormous. They are front-line medications in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and the spondyloarthropathies. In these diseases, they offer not only pain relief but the ability to actually alter the progression of the disease process. They are also used for a wide variety of other conditions, most of them associated with pain, such as tendinitis, osteoarthritis, and degenerative disc disease. And though the diagnostic terms commonly used for these disorders would imply inflammation, concepts regarding the underlying pathology of these latter conditions continue to evolve. The idea that chronic inflammation is the cause of them is being questioned because more precise information has become available that shows very little inflammatory reaction on histologic examination. Tendinitis, for example, may begin as overuse, leading to inflammation, but chronic pain is more often associated with neovascular changes in the local tissue without typical cellular findings of inflammation. Even the terminology used to describe these disorders is changing (from tendinitis to tendinosis or tendinopathy). Some studies suggest that they are beneficial, and some report no effect. Unfortunately, the outcomes that are measured, such as pain, are based mainly on subjective data, which may be influenced by the analgesic properties of these medications. Whether or not these drugs are appropriate for these disorders is a question that remains unanswered.

SIDE EFFECTS

Bone Healing

Recent studies have determined that NSAIDs suppress bone healing and bone formation. This has importance in three areas:

Central Nervous System

All of these drugs can cause central nervous system (CNS) symptoms. Most of them are minor but probably more common than appreciated. Dizziness, drowsiness, and confusion may occur. Salicylates, in particular, can cause mild lethargy. Confusion in the elderly can be especially troublesome, because it is this group that usually requires the medication the most. Depression may be subtle and hard to recognize unless the possibility that it could be drug induced is kept in mind. Low doses of amitriptyline may be needed at night for these patients. Tolmetin, sulindac, and especially indomethacin frequently cause such unpleasant symptoms as headache and nausea.

Renal and Hepatic

Ibuprofen, fenoprofen, and meclofenamate are most likely to cause renal problems, and all of the drugs can cause some loss of hepatic function. These effects do not seem related to dose or duration and are uncommon in healthy patients. Diclofenac and sulindac seem to have the greatest potential for hepatotoxicity. The symptoms resolve in most cases when treatment with the drug is stopped. Patients with impaired function should probably avoid the drugs. Because NSAIDs can decrease renal blood flow, many older patients with marginally compromised renal function may be susceptible to renal failure.

Fluid Retention

Salt and water retention are fairly common. Salt retention may even affect the lens and cornea and lead to blurred vision.

Gastrointestinal

Gastric irritation is common to all of these drugs, and the elderly patients who need them the most have three times more GI side effects than those younger than age 60. In most cases, the discomfort can be minimized by giving the drug with food. Ulcers that may develop are usually gastric rather than duodenal. As many as 60% of patients taking NSAIDs will develop gastric erosions. Many are asymptomatic. Because prostaglandins normally protect the gastric mucosa, injury appears to be caused by the inhibition of prostaglandin production. Erosions also may be caused by some direct local irritative effect. Although these drugs may have detrimental GI side effects, they are all that is available for the treatment of many inflammatory conditions. For those patients at greater risk of gastric ulceration (elderly or with a past history of ulcer disease), the COX-2 inhibitors are appropriate. Misoprostol (Cytotec) may also be helpful. An analogue of prostaglandin, misoprostol is effective in the prevention of gastric (not duodenal) ulcers caused by NSAIDs. It is recommended for use in those patients more likely to develop ulceration: (1) older (over 60 years) or debilitated patients, (2) those with a known ulceration or previous GI bleed, or (3) patients taking oral steroids. Cotreatment with misoprostol (200 mg four times a day) has been shown to be effective during NSAID use. However, not everyone taking NSAIDs should be treated with them, because the cost of the two drugs together would be prohibitive. Misoprostol also can cause diarrhea and is contraindicated during pregnancy (it may cause spontaneous abortion) and nursing. Other drugs such as H2 antagonists and antacids produced inferior results to misoprostol in preventing gastric ulceration, although even their use is often recommended on an empiric basis in patients at high risk.

Others

The antiplatelet effect of these drugs is well known, and any elective surgery may need to be postponed several days, depending on the half-life of the medication. Aspirin needs 7 to 12 days. NSAIDs are also not recommended in pregnant or nursing mothers, for whom acetaminophen remains the safest for analgesic purposes.

Aegerter E, Kirkpatrick JA. Orthopedic diseases, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1968.

Cohen MD, Abril A. Polymyalgia rheumatica revisited. Bull Rheum Dis. 2001;50:1-4.

Crofford LJ. Pharmaceutical treatment options for fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2004;6:274-280.

Flatt AE. The care of the rheumatoid hand, ed 2. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co, 1968.

Gatter RA. A practical handbook of joint fluid analysis. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1984.

Halverson PB, Derfus BA. Calcium crystal-induced inflammation. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:221-224.

ed 8. Hollander JL, McCarty DJ, editors. Arthritis and allied conditions. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1972.

Katz WA. Rheumatoid diseases, diagnosis, and management. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1977.

Kline NS. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. IV. JAMA. 1964;190:741-751.

Laskar FH, Sargison KD. Ochronotic arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52:653-666.

Lawrence SJ. Lyme disease: An orthopedic perspective. Orthopedics. 1992;15:1331-1342.

Maini SR. Infliximab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30:329-347.

McDonald JC, Milgrom F, Witebsky E. Primer of the rheumatic diseases. I. JAMA. 1964;190:127-140.

Murray DG. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. 3. JAMA. 1964;190:509-530.

Olsen NJ, Stein CM. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2167-2179.

Reynolds JC. Famotidine therapy for active duodenal ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:7-14.

Roubenoff R. Gout and hyperuricemia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:539-550.

Sagarin MJ. Pseudogout. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:373-374.

Simmons BP, Nutting JT, Bernstein RA. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clin. 1996;12:573-589.

Steere AC, Taylor E, McHugh GL, et al. The overdiagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA. 1993;269:1812-1816.

Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice. Gout. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1647-1655.

Wallace SL, Singer JZ. Therapy in gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988;14:441-457.