6 The Arthritic Lower Extremity

The arthritic hip

Pathology around the hip can be classified into three groups: intra-articular, extra-articular, and hip mimickers (Table 6-1).

| Intra-Articular | Extra-Articular | Hip Mimickers |

|---|---|---|

| Acetabular labral tears Ligamentum teres tears Femoroacetabular impingement Chondral defects Osteoarthritis Avascular necrosis Dysplasia |

Internal coxa saltans External coxa saltans Gluteal tears Muscle strains Piriformis syndrome Slipped capital femoral epiphysis Fractures |

Athletic pubalgia (sports hernia) Osteitis pubis Genitourinary disorders Intra-abdominal disorders Lumbar radiculopathy |

General Features of Osteoarthritis

According to Dieppe (1984), the following are general features of osteoarthritis:

Diagnosis of Hip Arthritis

The American College of Rheumatology lists several criteria for the diagnosis of OA of the hip.

Treatment of Hip Arthritis

Nonoperative Treatment

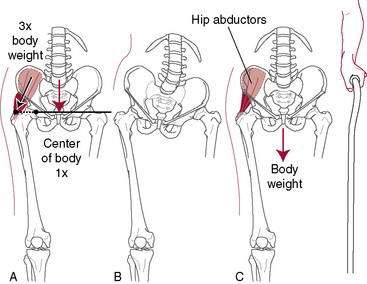

A cane in the opposite hand helps to unload the hip significantly (Fig. 6-1). A properly fitted cane should reach the top of the greater trochanter of the patient’s hip while wearing shoes. Doing stretching and strengthening exercises or joining a yoga class can be of surprising value in terms of regaining ROM because it is not uncommon that stiffness of periarticular structures (e.g., the inability to put on shoes and socks) rather than pain makes surgery necessary.

Medical Treatment

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used oral medication for OA. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effect, acetaminophen acts as an inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 in the central nervous system. Several clinical guidelines for the treatment of OA recommend its use for the relief of mild to moderate OA pain (American College of Rheumatology [www.rheumatology.org], Osteoarthritis Research Society International [www.oarsi.org], European League Against Rheumatism [www.eular.org]). A 2006 Cochrane review (Towheed et al.), however, found that although acetaminophen was significantly superior to placebo for pain relief, the clinical significance of the improvement was dubious. Although acetaminophen is among the safest oral analgesics, it does carry some risk for hepatic toxicity, although rarely at doses of 4 g/day or less.

Neutraceuticals such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are popular but unproven. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are synergistic endogenous molecules in articular cartilage. Glucosamine is thought to stimulate chondrocyte and synoviocyte metabolism, and chondroitin sulfate is believed to inhibit degradative enzymes and prevent formation of fibrin thrombi in periarticular tissues (Ghosh et al. 1992).

Injections of steroids can provide temporary relief but are not of lasting benefit and should not be done too frequently because of the risk of side effects such as weakening of the soft tissues around the hip joint and possibly the bone itself. More recently, hyaluronate injections have been reported to be effective in some patients (Migliore et al. 2009), whereas other have reported no benefit (Richette et al. 2009). This treatment currently is investigational for hip arthritis and is considered an “off-label” use.

Operative Options for Hip Arthritis

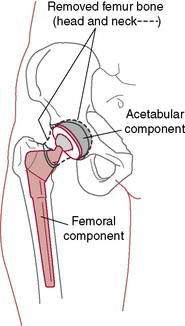

Osteotomies, such as pelvic and intertrochanteric osteotomies, were popular in the past, and they still may have a limited role in selected situations. Fusion still does have a role but in very early childhood only. The mainstay of surgical treatment is total hip replacement (Fig. 6-2). In general, for elderly patients with low activity demands, both the acetabular and the stem components can be cemented. For patients who are young and high demand, the current trend is to use noncemented implants. These are only general guidelines. In revisions with poor-quality bone, the surgeon makes fixation choices based on intraoperative findings.

Total Hip Replacement Rehabilitation: Progression and Restrictions

Morteza Meftah, MD; Amar S. Ranawat, MD; and Anil S. Ranawat, MD

The success of total hip replacement (THR) is a result of predictable pain relief, improvements in quality of life, and restoration of normal function (Brown et al. 2009). Postoperative rehabilitation is one of the factors that can affect outcomes after THR. The main goal of postoperative rehabilitation protocols is achieving maximal functional performance by focusing on reducing pain, increasing ROM, and strengthening the hip muscles (Brander et al. 1994) (see also page 435).

Because the majority of functional performance is gained within the first 6 months postoperatively (Gogia et al. 1994), a proper rehabilitation program that addresses the aforementioned goal is of paramount importance. Several factors influence the results of these programs, such as preoperative management, surgical approach, multimodal pain control modalities, hip precautions, postoperative protocols, weightbearing status, and the level of rehabilitative care.

Preoperative Management

Patient education regarding postoperative pain management, restrictions, independent walking, and proper rehabilitation is an important first step in achieving satisfactory results after THR. Preoperative classes can facilitate patients’ understanding of reasonable expectations of recovery, increase their motivation, and help expedite the rehabilitation learning process(Giraduet-Le Quintrec et al. 2003). Vukomanovic et al. reported that patients who both performed the “postoperative” exercises and received preoperative education demonstrated the ability to perform functional activities significantly earlier than those who were randomly assigned to the control group. These functional activities included being able to walk up and down stairs earlier, use the toilet and chair sooner, transfer independently, and ambulate independently.

Patient education also has been shown to be directly related to faster postoperative ambulation, reductions in hospital length of stay, and less use of narcotic pain medications (Spaulding 1995). A major part of preoperative educational classes should be dedicated to prevention of postoperative dislocation by appropriate explanation of hip precautions.

Although several studies have shown that preoperative strengthening exercises have a significant correlation with longer postoperative walking distance and may improve early return to ambulatory function after THR (Gilbey et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2002; Whitney and Parkman 2002), others have shown that these exercises have no significant impact on the outcomes (Gocen et al. 2004; Rooks et al. 2006).

Surgical Approach

One of the factors influencing postoperative recovery and rehabilitation is the surgical approach. The patient’s gait may be compromised with approaches in which the hip abductors are altered (i.e., lateral or anterolateral approaches). Inadequate repair or weakness of the abductor muscles after these approaches may result in prolonged limping. The posterolateral approach spares the hip abductors but is associated with a slightly higher dislocation rate. This dislocation rate can be reduced with the use of larger femoral heads and proper repair of the posterior soft tissues (Pellicci et al. 1998; Woo and Morrey, 1982). The direct anterior approach, although theoretically appealing, is technically demanding and may require fracture table and intraoperative fluoroscopy (Peak et al. 2005). Minimally invasive THR has been widely marketed, but the claims of significantly reduced pain, less morbidity, better function, and improved patient satisfaction appear to be unfounded (Khan et al. 2009). Based on recent reports, minimally invasive THR does not appear to affect the short-term or intermediate-term outcomes after the THR (Howell et al. 2004; Inaba et al. 2005; Lawlor 2005). Complications of minimally invasive THR include wound-healing problems, component malposition, and increased risk of femoral fractures (Howell et al. 2004; Lawlor 2005).

Multimodal Pain Management

Severe pain after THR is one of the greatest fears patients have before surgery and is the leading cause of delayed discharge. Pain remains a poorly understood, complex phenomenon that plays a significant role in limiting patients’ functional recovery and participation in postoperative physical therapy (Ranawat and Ranawat 2007). Optimal pain control promotes earlier ambulation and faster return to normal gait (Singelyn et al. 1998). Decreased postoperative range of motion due to pain commonly contributes to arthrofibrosis and inferior results (Ryu et al. 1993). A multimodal pain regimen is a relatively new concept that has shown excellent results in terms of improving postoperative pain, reducing the need for narcotic medications and increasing patients’ motivation and participation in postoperative physical therapy (Brown et al. 2009; Busch et al. 2006; Hebl et al. 2005; Maheshwari et al. 2006; Peters et al. 2006). The key to multimodal pain control is the use of various pain medications with different mechanisms of action that results in superior pain control while minimizing their adverse side effects. Several postoperative pain control protocols exist, including patient-controlled anesthesia pumps (PCA), femoral nerve blocks (FNBs), continuous or one-time psoas compartment block (cPCB), and continuous lumbar plexus block (cLPB) (Becchi et al. 2008; Siddiqui et al. 2007). The use of local infiltration through an intra-articular catheter after THR has been shown to reduce the hospital stay and reduce the opioid-related side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, compared to continuous epidural infusion (Andersen et al. 2007). Local periarticular injections have also been used in a multimodal pain regimen that has been shown to reduce postoperative pain and improve patient satisfaction and functional recovery (Pagnano et al. 2006; Parvataneni et al. 2007).

Hip Precautions

Postoperative hip restrictions are used to protect the soft tissue repair after a posterior approach and thereby avoid hip dislocation (Masonis and Bourne 2002). Table 6-2 presents the common precautions associated with each surgical approach; however, variations may exist regionally. These precautions can be difficult to adhere to and may interfere with the postoperative rehabilitation process (Peak et al. 2005). Dislocation after THA through the posterior approach commonly occurs when the hip is adducted past midline, internally rotated, and flexed more than 90 degrees. To prevent this, an abduction pillow (Fig. 7-48 in Chapter 7) is placed between the patient’s knees while in bed or a small cushion can be situated between the thighs while sitting (Rao and Bronstein 1991). In some cases, especially in revisions or in patients who are noncompliant, it may be necessary to use knee immobilizers or hip abduction orthoses for 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively to restrict hip adduction and flexion (Venditolli et al. 2006).

Table 6-2 Precautions Associated with Total Hip Arthroplasty Surgical Approaches

| Surgical Approach | Precautions |

|---|---|

| Anterior | Do not extend hip beyond neutral. No lying in prone. Do not externally rotate and extend the hip. Do not perform the bridging exercise. |

| Posterior | Do not flex the hip greater than 90 degrees. Do not internally rotate the hip beyond neutral. Do not adduct the leg beyond neutral. |

After an anterior or anterolateral approach, extreme external rotation, adduction, and extension should be avoided. Several reports have shown that removal of hip precautions after the anterolateral approach results in a faster return to normal activities with higher patient satisfaction and no ill effects on short-term dislocation rates (Peak et al. 2005; Talbot et al. 2002).

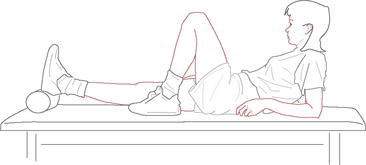

Postoperative Total Hip Arthroplasty Rehabilitation Programs

Although a wide variety of exercise programs exist based on surgeon preference and geographic location, most protocols include quadriceps sets, gluteal sets, ankle pumps, and active hip flexion (heel slides) exercises (Enloe et al. 1996). Progressive hip abductor strengthening is also advocated, as the abductors maintain the pelvis level during the stance phase and prevent tilting of the contralateral hip during the swing phase (Enloe et al. 1996; Soderberg 1986). Most exercise programs address this issue initially by concentric hip abduction in a supine position and later through isometric hip abduction against resistance (Munin et al. 1995). The straight-leg raising exercise has been shown to apply a force of 1.5 to 1.8 times body weight and should be allowed only when partial or full weightbearing is permitted (Davy et al. 1988). If pain occurs, hip flexion and knee extension exercises can be done separately with placement of a bolster under the knee to minimize hip stress (Davy et al. 1988; Trudelle-Jackson et al. 2002). Several reports have shown persistent quadriceps atrophy or weak thigh flexors of the operated hip compared to the contralateral hip (Bertocci et al. 2004; Reardon et al. 2001; Shih et al. 1994).

Functional tasks of daily living targeted in the rehabilitation program include weight transfer to the nonoperated hip, gait training on both level and uneven surfaces, stair climbing, and lower extremity dressing. Transferring of weight to the uninvolved side is initiated by leading with the nonoperated limb both into and out of bed and then is progressed to both sides of the bed. This method is also used with stair climbing: Patients are instructed to lead with the uninvolved hip while ascending and lead with the operated hip while descending the stairs to optimize control of body weight through the uninvolved leg (Strickland et al. 1992).

Weightbearing

Weightbearing restrictions after hip replacement, such as toe-touch weightbearing (TTWB) or partial weightbearing (PWB), directly affect the level of functional independence after surgery. PWB refers to 30% to 50% of the body weight, but studies have shown that patients have difficulty estimating and maintaining this percentage and commonly violate the restricted weightbearing (Davy et al. 1988). In TTWB, no more than 10% of body weight should be applied. TTWB is preferred over nonweightbearing (NWB) because the latter may actually create greater pressures over the hip joint as a result of muscle forces maintaining the correct pelvic positioning (Davy et al. 1988). Full weightbearing (FWB) has been shown to promote faster recovery and shorter hospital stays (Kishida et al. 2001). This is a result of reduced reliance on the upper extremities for weightbearing, resulting in earlier strengthening of the operative hip abductors and improved functional outcomes.

Assistive devices such as walkers, crutches, and canes are used to unload the operated joint and provide support and balance (Holder et al. 1993; Strickland et al. 1992). Progression from one to another is dependent on several factors such as age, comorbidities, and weightbearing restrictions. Walkers are usually the first choice after THR and provide the greatest stability by increasing the patient’s base of support and unloading the affected leg (Davy et al. 1988). Because walkers require the use of both hands, carrying objects and performing self-care activities are challenging. In addition, walkers occasionally do not fit through doorways and are not recommended for use on stairs. Rolling walkers have higher self-selected walking speeds than standard walkers (Palmer and Toms 1992). Most patients advance easily from gait training with a walker to crutches or a cane. Axillary and forearm crutches are more appropriate for younger, more agile patients because they allow faster gait and yield better energy efficiency in NWB healthy subjects (Holder et al. 1993), but they have the least stability and require more control of the lower extremity and overall balance (Palmer et al. 1992). A potential complication of axillary crutches is axillary nerve compression injuries from incorrect use (O’Sullivan and Schmitz 1988). Canes are usually used on the contralateral side of the hip replacement and can transfer 10% to 20% of body weight by decreasing vertical hip contact forces (Brander et al. 1994; Deathe et al. 1993; Stineman et al. 1996). The basic function of a cane is to extend the base of support and to provide stability. Canes should be used only for patients who are fully weightbearing. Canes are inexpensive, allow a reciprocal walking pattern, can be used on stairs, and can be sized according to the patients’ height. The crook of the handle should be even with the radial styloid process when the elbow is flexed at 15 to 30 degrees (O’Sullivan and Schmitz 1988).

Levels of Rehabilitative Care

Different rehabilitation settings include acute hospital care, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facilities, and home or outpatient rehabilitation centers. Selecting the appropriate postoperative rehabilitation that best serves the patient is often confusing to both the patient and health care professionals. In acute hospital care, postoperative physical therapy is usually started on the same day of surgery or the next morning. The goals for the first physical therapy session are to assess the patient’s mobility status and to initiate therapeutic activities. With the patient lying supine in the bed, the physical therapist should observe the patient’s positioning, assess for signs of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Table 6-3), note the state of the dressing, and record the ROM and strength of the uninvolved leg. If signs of a DVT are present or if there is excessive drainage noted on the dressing, the nursing staff should be immediately informed prior to continuing the treatment session.

| Lower leg swelling |

| Patient reporting pain in the calf and/or thigh |

| Redness in the calf |

| Pain reported by the patient when the calf and/or thigh are palpated |

Therapeutic exercises initiated during the initial visit may consist of lower extremity isometrics (quadriceps, hamstring, gluteal sets) and ankle pumps. Initially, a patient may be able to tolerate only passive ROM; however, he or she should be able to demonstrate increased active ROM tolerance over the course of the inpatient stay. Therapeutic exercises frequently are added daily to the patient’s routine. Table 6-4 presents a sample therapeutic exercise progression during the first postoperative week.

Table 6-4 Sample Week 1 Total Hip Replacement Postoperative Exercise Program*

| Postoperative Day | Prescribed Exercises |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | Isometrics (quadriceps sets, hamstring sets, gluteal sets) Ankle pumps |

| Day 2 | Continue previous exercises Supine hip range of motion within allowed ranges (passive to active as tolerated) Hip abduction active assisted to active range of motion Heel slides (heel toward buttocks) Bridging |

| Days 3–4 | Continue previous exercises Sitting heel raises Large arc quads |

| Days 5–7 | Continue previous exercises Mini-squats Standing hip flexion to 90 degrees (surgical leg) Standing hip extension (surgical leg) Standing hip abduction (surgical leg) Forward step-up |

* This sample program is based on a posterior surgical approach (see also page 435).

Comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation is different from acute hospital care because it is more focused on physical therapy and interdisciplinary treatment in combination with intensive family training. Inpatient rehabilitation is reserved for patients who require more than a few days of continuous skilled care, are able to physically tolerate at least 3 hours of therapy per day, and have a good chance of returning home within a reasonable time frame (Stineman et al. 1996). Medical management is similar to the acute hospital care setting. Reports have shown that older patients without family support and patients with comorbid medical conditions usually need inpatient rehabilitation after THR (Munin et al. 1995; Weingarten et al. 1994). The subacute nursing facility (SNF) was developed as a complement to inpatient rehabilitation and has grown as an alternative to it. The SNF is reserved for patients who cannot tolerate the 3 hours of therapy per day required in an inpatient rehabilitation program and are not at risk for medical instability (Haffey and Welsh 1995).

Postoperative protocol after primary total hip replacement

Management of Common Problems After Total Hip Replacement

Gait Faults

Gait faults should be watched for and corrected. Chandler (1982) pointed out that most gait faults either are caused by or contribute to flexion deformities at the hip. These faults generally are attributable to the patient’s attempts to avoid extension of the involved hip because such extension causes an uncomfortable stretching sensation in the groin.

Outpatient Total Hip Arthroplasty Physical Therapy Protocol

Exercises to increase muscle strength include the following:

Progressive overload to the muscles can be applied manually by the application of ankle weights or with the use of elastic resistance bands. The initial exercise prescription should consist of one to three sets of 15 to 20 repetitions. This volume of training will help to improve muscular endurance while minimizing the risk of excessive postexercise muscular soreness or pain. As endurance capacity increases, strength training can be increased to volumes of two to four sets of 6 to 10 repetitions. Table 6-5 presents frequently prescribed therapeutic exercises that address muscular weakness. The exercises are grouped by the muscles trained and in the order of difficulty.

Table 6-5 Therapeutic Exercises Frequently Prescribed in the Outpatient Orthopedic Physical Therapy Setting

| Muscle Group | Exercises* |

|---|---|

| Hip flexors | Isometric hip flexion Sitting hip flexion (no greater than 90 degrees initially) Manually resisted active hip flexion (patient supine, no greater than 90 degrees initially) Straight leg raise Standing hip flexion (no greater than 90 degrees initially) Standing hip flexion—full ROM when precautions are lifted. Multihip machine flexion |

| Hip extensors | Gluteal sets Bridging Manually resisted hip extension (patient supine with leg starting in a position of hip flexion) Standing hip extension Bridging with lower extremity extension Prone hip extension Multihip machine extension Forward step-up Mini-squats Lateral step-down |

| Hip abductors | Lateral heel slides (hip abduction supine) Manually resisted hip abduction (patient supine) Standing hip abduction Multihip machine abduction Side-lying hip abduction (when precautions are lifted) Lateral step-downs |

| Hip adductors | Hip adductor isometrics (with the patient supine and the hip in neutral or slightly abducted) Manually resisted hip adduction to neutral from a hip-abducted position Standing hip adduction (when precautions are lifted) Side-lying hip adduction (when precautions are lifted) |

| Hip external rotators | Manually applied hip external rotation isometric (patient supine in hook-lying) Manually applied hip external rotation with active hip external rotation from neutral (patient supine in hook-lying) |

| Hip internal rotators | Manually applied hip internal rotation isometric (patient supine in hook-lying with hip positioned in neutral or slightly externally rotated) Manually applied hip internal rotation with active hip internal rotation from a starting position of external rotation to neutral (patient positioned in supine) |

| Knee extensors | Quadriceps set Short arc quad Straight leg raise Large arc quad Forward step-up Mini-squat Lateral step-down Leg press |

| Knee curl | Hamstring sets Heel slides toward buttock Standing hamstring curls Leg curl machine (sitting): double-legged and single-legged curls |

| Gastrocnemius and soleus | Sitting heel raise Standing heel raise |

* Exercises are presented by their relative degree of difficulty.

Return to Sport After Total Hip Replacement

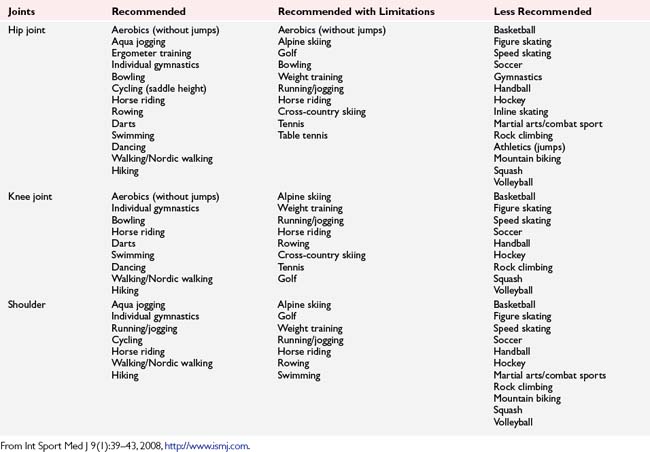

Physical activity levels may have an impact on the lifespan of the total hip replacement. Wear and tear on the replaced joint or a traumatic event may necessitate a revision surgery at a later date; however, having a hip replaced does not mean that one must end his or her recreational or sport pursuits. Exercise and activity are necessary for maintaining overall health. Instead of restricting activity, physicians have developed recommendations and guidelines for those who wish to return to activities that are more strenuous than walking. Table 6-6 presents examples of activities and sports, their associated levels of impact on the hip replacement, and recommendations as to the safety of performing and participating in a particular sport.

Table 6-6 Sport Participation Recommendations and Associated Levels of Impact on the Total Joint Replacement

| Level of Impact | Examples | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Stationary cycling Calisthenics Golf Stationary skiing Swimming Walking Ballroom dancing Water aerobics |

Can improve general health Desirable for most patients, but may increase rate of wear Orthotics and activity modifications can reduce impact loads Concentration on conditioning and flexibility rather than strengthening |

| Potentially low | Bowling Fencing Rowing Isokinetic weight lifting Sailing Speed walking Cross-country skiing Table tennis Jazz dancing and ballet Bicycling |

Desirable for most patients, but may increase rate of wear Requires preactivity evaluation, monitoring, and development of guidelines by surgeon Balance and proprioception must be intact Orthotics and activity modifications can reduce impact loads Emphasize high number of repetitions with minimal resistance |

| Intermediate | Free-weight lifting Hiking Horseback riding Ice skating Rock climbing Low-impact aerobics Tennis In-line skating Downhill skiing |

Appropriate only for selected patients Require preactivity evaluation, monitoring, and development of guidelines for participation by surgeon Excellent physical condition is necessary Orthotics, impact absorbing shoes, and activity modification frequently necessary |

| High | Baseball/softball Basketball/volleyball Football Handball/racquetball Jogging/running Lacrosse SoccerWater skiing Karate |

Should be avoided Significant probability of injury and need for revision |

From Clifford PE, Mallon WJ. Sports participation for patients with joint replacements based upon level of impact loading. Clin Sports Med 24(1):182, 2005. Table 1.

Table 6-7 provides a list of sports that are considered acceptable for participation, those that are possibly acceptable for participation, and those that are not recommended. Sports are designated “possibly acceptable” or “not recommended” based on the risk of falling or traumatic contact. Falling or experiencing traumatic forces may contribute to hip dislocation, hip fracture, or failure of the hip replacement.

Table 6-7 Sports Participation Recommendations for Patients with a Total Hip Replacement

| Acceptable | Possible | Not Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Ballroom dancing | Ballet dancing | Baseball/softball |

| Bicycling | Calisthenics | Basketball |

| Bowling | Downhill skiing | Football |

| Cross-country skiing | Fencing | Handball/racquetball |

| Golf | Hiking | Karate |

| Horseback riding | Jazz dancing | Lacrosse |

| Ice skating | Jogging/running | Soccer |

| In-line skating | Rock climbing | Volleyball |

| Low-impact aerobics | Table tennis | |

| Rowing | Tennis | |

| Sailing | Water skiing | |

| Speed walking | ||

| Stationary cycling | ||

| Stationary skiing | ||

| Swimming | ||

| Walking | ||

| Water aerobics |

Adapted from Clifford PE, Mallon WJ. Sports participation for patients with joint replacements based upon level of impact loading. Clin Sports Med 24(1):183, 2005. Table 2.

Sport-Specific Exercises for the Golfer with a Total Hip Replacement

It is generally agreed that golfing is an acceptable sport to return to and that it places a low degree of stress on the hip implant (see Fig. 7-62). Because of the multiplanar nature of the golf swing and the unique forces placed on the body (specifically the core), the rehabilitation and strength training program for the golfer who has had a total hip replacement should include sport-specific exercises once the patient’s physician has lifted hip precautions. Most sport-specific exercises should address core stability and multiplanar movement patterns.

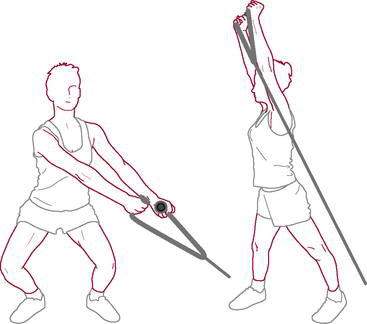

Exercises to increase core endurance capacity include front plank with hip extension (see Fig. 7-63), the bird dog, and the side plank. With improved core endurance, the golfer should be prescribed multiplanar exercises such as the lunge with trunk rotation (see Fig. 7-64), kettle bell squats (Fig. 6-3), plyometric ball tosses (see Fig. 7-65), and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation chop and lift patterns performed against resistance (Fig. 6-4).

The Arthritic Knee

| Risk Factor | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Older age | Incidence increases with age |

| Female sex | Greater prevalence of OA in women |

| Obesity | Higher incidence of OA in patients who are obese |

| Osteoporosis | Associated with higher incidence and slower progression of OA |

| Occupation | Higher incidence of OA with repetitive squatting, kneeling, bending |

| Sports activities | Increased risk of OA with high-impact contact, torsional loads, and overuse |

| Previous trauma | Increase in OA in athletes postinjury |

| Muscle weakness/dysfunction | Increases in OA with inactivity, poor training, and injury |

| Proprioceptive deficit | Increases in OA with age, comorbid illness, and anterior cruciate ligament injury |

| Genetic factors | Neither preventable or modifiable—variable expression |

Bosomworth NJ. Can Fam Phys 55:871–878, 2009.

The diagnostic criteria for OA are not clearly defined, in part because of discordance between symptoms and radiologic evidence of OA. What appears on radiographs to be substantial OA may not create severe symptoms, whereas relatively mild OA on radiographs may produce disabling pain and stiffness (Bland and Cooper 1984, Dieppe et al. 1997, Felson et al. 2004, Hannan et al. 2000, Kellgren and Lawrence 1952, Lawrence et al. 1966, Lethbridge-Cejku et al. 1995, Scott et al. 1995, Szebenyi et al. 2006). The American College of Rheumatology lists six clinical criteria, three of which must be met, in addition to pain in the knee, for the diagnosis of OA of the knee:

Diagnosis

A thorough history and examination of the arthritic knee should obtain the following information:

Treatment Options

Physical Therapy

Both manual therapy and exercise have been shown to be beneficial for those with knee OA. Studies by Deyle et al. (2000, 2005) have demonstrated a significant effect on pain and physical function with use of manual therapy in treatment of those with knee OA. Because knee OA may be partially caused by restrictions of periarticular mobility as a result of adhesions from repetitive bouts of inflammatory reagents, biomechanical forces at the joint level may be responsible for some of the pain and disease progression. Manual therapy may decrease restricted mobility, allowing increased excursion of these tissues and allowing reduced pain and stiffness. This reduction in pain may allow patients to participate more fully in therapeutic exercise programs such as those described here.

Currier et al. (2007) developed a clinical prediction rule that when followed appears to provide short-term relief in patients with knee pain and clinical evidence of knee OA. A patient with symptomatic knee OA may benefit from hip mobilizations if they have two or more of the following criteria: (1) hip or groin pain or paresthesia, (2) anterior thigh pain, (3) passive knee flexion less than 122 degrees, (4) passive hip medial (internal) rotation less than 17 degrees, and (5) pain with hip distraction.

Furthermore, exercise has been shown to be effective in multiple studies in patients with OA (Baker et al. 2001; Fitzgerald and Oatis 2004; Deyle et al. 2005; Fransen et al. 2001, 2002; Petrella and Bartha 2001; Peloquin et al. 2002). Therapeutic exercises that have been proved to be beneficial include the following:

Systematic reviews and randomized clinical trials on the immediate effect of exercise on knee OA have demonstrated increased function and decreased pain (Baar et al. 1999, Rogind et al. 1998, O’Reilly et al. 1999), but at longer-term follow-up there appears to be a decline in effects over time (Baar et al. 2001). Therefore, a continued program or at minimum followup exercise sessions must be stressed to maintain positive results.

Quadriceps strengthening has been a mainstay of conservative treatment for knee OA because muscle weakness can lead to functional disability (Anderson and Felson 1988, Baker et al. 2004, Brandt et al. 1998, Fisher and Pendergast 1997, Slemenda et al. 1998, Wessel 1996). Very strong quadriceps can considerably delay the necessity for surgery. If the patella is painful, extension exercises should be carried out only over the last 20 degrees of extension. Activities such as deep squatting, kneeling, and stair climbing that increase the patellofemoral joint reaction forces (PFJRFs) increase pain. Those activities should be avoided.

Bosomworth (2009) found in a literature review that the best evidence suggests that exercise, at least at moderate levels, does not accelerate knee OA and running seems to be particularly safe. There might be an increased risk of OA with competitive sports participation, particularly when started early in life, although the presence of OA following this does not typically lead to an increased level of disability. Other problems may increase risk such as obesity, trauma, occupational stress, and lower extremity alignment problems.

Aerobic exercise may be beneficial because it not only increases cardiovascular endurance, but also helps with weight control and reduction. Aerobic programs can also reduce pain and stiffness, improve and maintain balance, and increase walking speed and agility (Minor et al. 1989, Rogind et al. 1998). Both land-based and aquatic-based programs have been shown to be beneficial for those with knee OA (Wyatt et al. 2001). A randomized controlled trial (Hinman et al. 2007) found that patients who participated in aquatic physical therapy had less pain and joint stiffness and greater physical function, quality of life, and hip muscle strength than those who did not. The authors suggested several benefits over land-based physical therapy: buoyancy reduces loading across joints affected by pain and allows performance of closed-chain exercises that may be too difficult on land; water turbulence can be used as a method of increasing resistance; the percentage of body weight borne by the affected extremity can be increased or decreased by varying the depth of immersion; and the warmth and pressure of the water may further assist with pain relief, swelling reduction, and ease of movement.

Lin et al. (2009) compared nonweightbearing proprioceptive training and strength training in more than 100 patients with knee OA and found that both types significantly improved function: Proprioceptive training led to greater improvement in walking speed on spongy surfaces, while strength training resulted in a greater improvement in walking speed on stairs. They suggested that non-weightbearing exercise may be an option in individuals who are unable to exercise in a weightbearing position because of pain or other reasons.

Unloading Braces

Counterforce bracing can be used to “unload” the medial joint. Typically, these braces are custom made/fit to the patient to allow an intrinsic valgus correction of several degrees that will allow small individual alterations to be made depending on symptoms. The brace, by applying a valgus stress to the knee, may allow a partial restoration of the more “normal neutral” knee position that has been reduced by loss of articular cartilage. Biomechanical studies have shown that pain, joint position sense, strength, and function can be altered by an unloading brace (Finger and Paulos 2002, Lindenfeld et al. 1997, Pollo et al. 2002, Self et al. 2000). More recently, Ramsey et al. (2007) determined that a brace in neutral alignment performs as well or better than one that has a valgus alignment for those with medial compartment arthritis. They suggested that the symptom relief and improved function may actually be the result of diminished muscle cocontractions rather than from actual medial compartment unloading.

Insoles

Keating et al. (1993) found that of 85 patients with medial compartment arthritis in the knee, more than 75% had significant improvement in Hospital for Special Surgery pain scores at 12 months follow-up while using a lateral-wedge insole. By placing the calcaneus in a valgus position, a medial unloading may take place more proximal up the kinematic chain at the knee. Sasaki and Yasuda in two articles (Sasaki and Yasuda 1987, Yasuda and Sasaki 1987) both demonstrated reduced medial joint surface loading with the use of a lateral-wedge insole. For most, the cost effectiveness of a lateral-wedge insole is its greatest benefit.

Weight Loss

Weight loss may be an important adjunct to other therapies. Although the mechanism is not clearly understand yet, it seems empirically that people who are overweight or obese may have an increased risk for developing knee OA. Reduced body weight may help by reducing loads on weightbearing joints (Felson 1996, Felson et al 1997; Messier et al. 2000; Toda et al. 1998) and improving overall physical function (Christensen et al. 2005). Recent evidence has shown that, although obesity may be a risk factor for incident knee OA, no overall relationship between obesity and the progression of knee OA could be found in a study of 5159 knees of patients who were overweight (Niu et al. 2009). Niu et al. (2009) found obesity not to be associated with OA progression in knees with varus alignment; however, it did increase the risk of progression in knees with neutral or valgus alignment. Therefore, location of OA may predicate effectiveness of weight loss in preventing progression of structural damage in OA knees. Weight loss alone may not be effective in those with varus alignment placing increased stress on the medial knee compartment.

Viscosupplementation

Viscosupplementation is a highly used palliative treatment for knee OA because of ease of application and theoretical ability to relieve symptoms by restoring and replenishing hyaluronate component into the knee joint. Multiple studies have demonstrated that these forms of treatment are clinically safe and suggest that this treatment may be effective for short-term symptom relief in patients with OA and may delay the need for total knee arthroplasty (Bellamy et al. 2006, Parker et al. 2006, Dagenais 2006, Divine et al. 2007, Conrozier et al. 2008, Chevalier et al. 2010); however, these positive findings may be a result of a robust placebo effect (Brockmeier et al. 2006). Even if hyaluronate supplementation does partially restore intraarticular lubricating properties, it is not a form of treatment that is effective for those with severely damaged articular cartilage (Chen et al. 2005).

Operative Treatment

Arthroscopic débridement is of temporary if any value in arthritic knees, simply cleaning out the tags and meniscal tears and flushing from the joint fluid that contains pain-producing peptides. Cole and Harners’ (1999) article on the evaluation and management of knee arthritis provides an excellent overview on arthroscopy in patients with knee arthritis.

Livesley et al. (1991) compared the results in 37 painful arthritic knees treated with arthroscopic lavage by one surgeon against those in 24 knees treated with physical therapy alone by a second surgeon. The results suggested that there was better pain relief in the lavage group at 1 year. Edelson et al. (1995) reported that lavage alone had good or excellent results in 86% of their patients at 1 year and in 81% at 2 years using the Hospital for Special Surgery scale.

Jackson and Rouse (1982) reported on the results of arthroscopic lavage alone versus lavage combined with débridement, with 3-year followup. Of the 65 patients treated with lavage alone, 80% had initial improvement, but only 45% maintained improvement at follow-up. Of the 137 patients treated with lavage plus débridement, 88% showed initial improvement and 68% maintained improvement at follow-up. Gibson et al. (1992) demonstrated no statistically significant improvement with either method, even in the short term.

The true efficacy of lavage with or without débridement is controversial. More recent randomized controlled studies performed by Kirkley et al. (2008) and Moseley et al. (2002) found no benefit to arthroscopic lavage in patients with moderate to severe arthritis of the knee.

General Considerations

Operative treatment frequently is required for disabling knee pain, particularly in patients with post-traumatic knee OA. Reconstruction options include osteotomy, arthrodesis, and arthroplasty. In general, corrective osteotomy is done in younger patients with single-compartment degenerative change and angular malalignment. Osteotomy that corrects the angular malalignment also unloads the arthritic compartment and can delay disease progression and the need for total knee arthroplasty. Relative contraindications to osteotomy include tricompartmental arthritis, symptomatic patellofemoral degenerative changes, inflammatory arthritis, and age older than 60 years (Bedi and Haidukewych 2009). A downside to osteotomy is that changing the joint-line orientation with the osteotomy increases the technical difficulty of ensuing total knee arthroplasty.

For large, isolated traumatic lesions in young patients, fresh osteochondral allografting has been done in conjunction with the unloading osteotomy, with about 85% graft survival at 10 years (Ghazavi et al. 1997, Gross et al. 2005). Arthrodesis can be effective in relieving pain, but the functional limitations are substantial and ipsilateral back and hip pain may develop because of increased stress on these joints. Conversion of knee arthrodesis to total knee arthroplasty is difficult, has a high complication rate, and produces less than excellent outcomes.

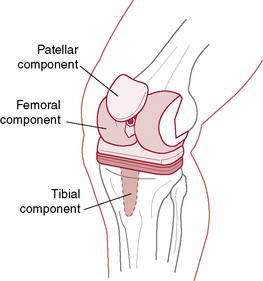

Total Knee Arthroplasty Rationale

Many surgeons use identical routines after total knee replacement, whether the implants are cemented or noncemented (Fig. 6-5). Their rationale is that the initial fixation of noncemented femoral and tibial components is in general so good that loosening is uncommon. The tibia is largely loaded in compression. The stability achieved with pegs, screws, and stems on modern implants is now adequate to allow full weightbearing. However, if the bone is exquisitely soft, weightbearing should be delayed. The progression to weightbearing, therefore, must be based solely on the surgeon’s discretion and intraoperative observations.

Management of Rehabilitation Problems After Total Knee Arthroplasty

Recalcitrant Flexion Contracture (Difficulty Obtaining Full Knee Extension)

Total Knee Replacement Protocol

David A. James, PT, DPT, OCS, CSCS, and Cullen M. Nigrini, MSPT, MEd, PT, ATC, LAT

Recent evidence indicates extensive variation in outcome measures used in clinical trials of knee and hip arthroplasty published since 2000. Riddle et al. (2009) found this heterogeneity lead to confusion in attempts at conducting systematic reviews and applying evidence to clinical practice. More confusion is created when the available literature reports little difference in long-term outcomes between therapy, home exercise, and CPM groups. Minns-Lowe et al. (2007) in a meta-analysis found physiotherapy to result in short-term benefit following total knee arthroplasty, although differences were minimal after 1 year.

Because of the lack of a guiding consensus behind rehabilitation protocols, clinicians must continue to utilize their skills and apply their knowledge. Each patient must be given individual tasks based on individual goals. Valtonen et al. (2009) concluded that the major goals for musculoskeletal rehabilitation are to restore a person’s mobility and functional capacity while preventing mobility disability. These authors felt that muscle power needed to be a focus of rehabilitation, finding significant power deficits in the postoperative limb in bilateral comparison 10 months after joint replacement. Strength should remain a focal point of rehabilitative activity, and the majority of patients benefit from strength training. Balance, mobility, coordination of movement, and gait should all be addressed also. Functional movement cannot be overlooked, and total body progression must take place for a patient to truly benefit from rehabilitation. Compensatory patterns developed while with pain and dysfunction can be identified and addressed now that the pain of the arthritic knee has been treated. All of these factors must be adjusted for each patient depending on their progress, goals, and desired outcomes (Rehabilitation Protocol 6-1).

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 6-1A Total Knee Replacement Exercise

Overall patient health, age, prior level of function, and patient progress may change.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 6-1B Total Knee Arthroplasty

Mintken PE, Carpenter KJ, Eckhoff D, Kohrt WM, Stevens JE: Early neuromuscular electrical stimulation to optimize quadriceps function after TKA: a case report, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 37:364-371, 2007.

Inpatient Rehabilitation Exercise Program

Postoperative Day 1

Postoperative Day 2

Postoperative Days 3–5 (or on discharge to rehabilitation unit)

Outpatient Rehabilitation Exercise Program

Range of Motion

Strength

Functional Activities

If patients are staying active longer, returning to activities will more often include return to sport. DeAndrade (1993) recommended return to sport by evaluating the demands of each sport. He concluded that high-impact sports such as jogging, racquetball and tennis, and jumping sports including basketball and volleyball, should be avoided. More recently, the International Federation of Sports Medicine (www.FIMS.org) released a position statement on return to sport following joint replacement. They pointed out that joint implants have dramatically risen in popularity over the past 20 years and indications for the procedure have also expanded. Younger patients are undergoing total joint replacement and may have higher levels of desired activity following rehabilitation.

The group agreed with the general trend that lower-impact sports with cyclic performance and low-impact force are recommended. Evidence suggests that low-impact exercise can improve clinical outcomes. The difference in this position statement is to argue against automatic dismissal of return to high-impact sport. The group felt this should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. They do note avoidance of forces that might result in luxation relative to the surgical technique and sports with increased injury rates. Seyler et al. (2006) agree there is conflicting advice for high-impact sport return and careful selection is needed, as are randomized controlled trials within this topic. Several considerations were identified by the FIMS to help determine the risks and rewards of return to a particular sport.

A patient’s prior experience in his or her sport should play a major role in the decision. They also feel 6 months should have passed prior to resuming heavy activity and the patient should be systemically cleared for activity. Interaction with or evaluation by the patient’s general physician, cardiologist, or internist can offer support in these areas. Radiologic evidence of proper axial alignment with no signs of loosening should also be confirmed. As far as contraindications, instability of the joint, loosening of the implant, and infection were listed. Relative contraindications were listed as prior revision of the endoprosthesis, muscular insufficiency, and obesity (body mass index >30). Table 6-8 lists the recommendations for return to sport as per the FIMS. Because of limited data on sport return, Healy et al. (2007) suggest physicians should provide information for the patient to evaluate the risk and then recommend appropriate athletic activities.

Table 6-8 Recommended, Recommended with Limitations, and Less Recommended Types of Sport After Total Joint Replacement of Hip, Knee, and Shoulder Joints

The literature does contain some sport-specific return-to-play data. Wylde et al. (2008) evaluated 2085 patients 1 to 3 years after total hip or total knee arthroplasty and found 61.4% returned to their sports including swimming, walking, and golf, whereas only 26% were unable to return as a result of the joint replacement. Jackson et al. (2006) reported on 151 golfers, finding 57% of patients who received total knee arthroplasty returned to golf 6 months postoperatively. Of these golfers, 81% noted less pain and were golfing as often as or more frequently than they were prior to the operative procedure. Of these golfers, 86% reported utilizing a golf cart, raising the question of desire versus ability to walk long distance.

Although objective discharge criteria following surgery exist and are listed in Rehabilitation Protocol 6-1, objective data should also be obtained. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) has been validated in the literature as reliable, valid, and responsive (Roos and Toksvig-Larsen 2003). The KOOS was developed as an extension of the Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) and can be downloaded at http://www.koos.nu. The WOMAC is also a viable option, as are the Knee Society Score, Global Knee Scale, and standard forms such as the SF-36.

Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: Are we asking the wrong questions? Br J Rheumatol. 1984;23(3):161. Aug

Ghosh P., Smith M., Wells C. Second line agents in osteoarthritis. In: Dixon J.S., Furst D.E., editors. Second Line Agents in the Treatment of Rheumatic Diseases. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1992.

Migliore A., Bizzi E., Massafra U., et al. Viscosupplementation: a suitable option for hip osteoarthritis in young adults. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13:465-472.

Richette P., Ravaud P., Conrozier T., et al. Effect of hyaluronic acid in symptomatic hip osteoarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:824-830.

Anderson J.J., Felson D.T. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:179-189.

Baar M.E. van, Assendelft W.J.J., et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1361-1369.

Baker K.R., Nelson M.E., Felson D.T., et al. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1655-1665.

Baker K.R., Xu L., Zhang Y., et al. Quadriceps weakness and its relationship to tibiofemoral and patellofemoral knee osteoarthritis in Chinese: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1815-1821.

Baar M.E. van, Dekker J., Oostendorp R.A.B., et al. Effectiveness of exercise in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: Nine months’ follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1123-1130.

Bedi A., Haidukewych G.J. Management of the posttraumatic arthritic knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:88-101.

Bellamy N., Campbell J., Robinson V., et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2006. CD005321

Bland J.H., Cooper S.M. Osteoarthritis: a review of the cell biology involved and evidence for reversibility: management rationally related to known genesis and pathophysiology. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1984;14:106-133.

Bosomworth N.J. Exercise and knee osteoarthritis: benefit or hazard? Can Fam Phys. 2009;55:871-878.

Brandt K.D., Heilman D.K., Mazzuca S., et al. Quadriceps weakness and osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Int Med. 1998;127:97-104.

Chen A.L., Mears S.C., Hawkins R.J. Orthopaedic care of the aging athlete. J Am Aca Orthop Surg. 2005;13(6):407-416.

Christensen R., Astrup A., Bliddal H. Weight loss: The treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:20-27.

Cole B.J., Harner C.D. Degenerative arthritis of the knee in active patients: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:389-402.

Currier L.L., Froehlich P.J., Carow S.D., et al. Development of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with knee pain and clinical evidence of knee osteoarthritis who demonstrate a favorable short-term response to hip mobilization. Phys Ther. 2007;87(9):1106-1119.

Dagenais S. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) for knee osteoarthritis. Issues Emerg Health technol. 2006;94:1-4.

Deyle G.D., Allison S.C., Matekel R.L., et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2005;85(12):1301-1317.

Deyle G.D., Henderson N.E., Matekel R.L., et al. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:173-181.

Dieppe P.A., Cushnaghan J., Shepstone L. The Bristol ‘OA500’ study: progression of osteoarthritis (OA) over 3 years and the relationship between clinical and radiographic changes at the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:87-97.

Divine J.G., Zazulak B.T., Hewett T.E. Viscosupplementation for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;445:113-122.

Edelson R., Burks R.T., Bloebaum R.D. short-term effects of knee washout for osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:345-349.

Felson D.T. Weight and osteoarthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:430-432.

Felson D.T., Hang Y., Hannan M.T., et al. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:728-733.

Finger S., Paulos L.E. Clinical and biomechanical evaluation of the unloading brace. J Knee Surg. 2002;15(3):155-158. discussion 159

Fisher N.M., Pendergast D.R. Reduced muscle function in patients with osteoarthritis. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1997;29:213-221.

Fitzgerald G.K., Oatis C. Role of physical therapy in management of knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:143-147.

Fransen M., Crosbie J., Edmonds J. Physical therapy is effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:156-164.

Fransen M., McConnell S., Bell M. Therapeutic exercise for people with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1737-1745.

Ghazavi M.T., Pritzker K.P., David A.M., et al. Fresh osteochondral allografts for post-traumatic osteochondral defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:1008-1013.

Gibson J.N., White M.D., Chapman V.M., et al. Arthroscopic lavage and debridement for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:534-537.

Gross A.E., Shasha N., Aubin P. Long-term followup of the use of fresh osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:79-87.

Hannan M.T., Felson D.T., Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1513-1517.

Hinman R.S., Heywood S.E., Day A.R. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:32-43.

Jackson R.W., Rouse D.W. The results of partial arthroscopic meniscectomy in patients over 40 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:481-485.

Keating E.M., Faris P.M., Ritter M.A., et al. Use of lateral heel and sole wedges in the treatment of medial osteoarthritis of the knee. Orthop Rev. 1993;22:921-924.

Kellgren J.H., Lawrence J.S. Rheumatism in minors, II: X-ray study. Br J Intern Med. 1952;9:179-207.

Kirkley A., Birmingham T.B., Litchfield R.B., Giffin J.R., Willits K.R., et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1097-1107.

Lawrence J.S., Bremner J.M., Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis: prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966;25:1-23.

Lethbridge-Cejku M., Scott W.W.Jr, Reichle R., Ettinger W.H., Zonderman A., Costa P., et al. Association of radiographic features of osteoarthritis of the knee with knee pain: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:182-188.

Lin D.H., Lin C.H., Lin Y.F., et al. Efficacy of 2 non-weight-bearing interventions, proprioception training versus strength training, for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:450-457.

Lindenfeld T.N., Hewett T.E., Andriachhi T.P., et al. Joint loading with valgus bracing in patients with varus gonarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;344:290-297.

Livesley P.J., Doherty M., Needoff M., et al. Arthroscopic lavage of osteoarthritis knees. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:922-926.

Messier S.P., Loeser R.F., Mitchell M.N., et al. Exercise and weight loss in obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: A preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1062-1072.

Minor M., Hewett J., Webel R., et al. Efficacy of physical conditioning exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1396-1405.

Moseley J.B., O’Malley K., Petersen N.J., Menke T.J., Brody B.A., et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):81-88.

Niu J., Zhang Y.Z., Torner J., et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiologic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Care Res. 2009;69:329-335.

O’Reilly S.C., Muir K.R., Doherty. Effectiveness of home exercises on pain and disability from osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:15-19.

Peloquin L.B.G., Fauthier P., Lacombe G., et al. Effects of cross-training exercise program in persons with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1737-1745.

Petrella R.J., Bartha C. Home based exercise therapy for older patients with knee osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: nine months’ follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1123-1130.

Pollo F.E., Otis J.C., Backus S.I., et al. Reduction of medial compartment loads with valgus bracing of the osteoarthritic knee. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):414-421.

Ramsey D.K., Briem K., Axe M.J., et al. A mechanical theory for the effectiveness of bracing for medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89A:2398-2407.

Rogind H., Bibow-Nielsen B., Jensen B., et al. The effects of a physical training program on patients with osteoarthritis of the knees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1421-1427.

Sasaki T., Yasuda K. clinical evaluation of the treatment of osteoarthritic knees using a newly designed wedged insole. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;221:181-187.

Scott W.W.Jr, Reichle R., Ettinger W.H., Zonderman A., Costa P., et al. Association of radiographic features of osteoarthritis of the knee with knee pain: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:182-188.

Self B.P., Greenwald R.M., Pflaster D.S. A biomechanical analysis of a medial unloading brace for osteoarthritis in the knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13(4):191-197.

Slemenda C., Heilman D.K., Brandt K.D., et al. Reduced quadriceps strength relative to body weight: a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(11):1951-1959.

Szebenyi B., Hollander A.P., Dieppe P., et al. Associations between pain, function, and radiographic features in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):230-235.

Toda Y., Toda T., Tkemura S., et al. Changes in body fat, but not boney weight or metabolic correlates of obesity. Is it related to symptomatic relief of obese patients with knee osteoarthritis after a weight control program? J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2181-2186.

Wessel J. Isometric strength measurements of knee extensors in women with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:328-331.

Wyatt F.B., Milam S., Manske R.C., et al. The effects of aquatic and traditional exercise programs on persons with knee osteoarthritis. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(3):337-340.

Yasuda K., Sasaki T. The mechanics of treatment of the osteoarthritic knee with a wedged insole. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;215:162-172.

Adams M.E., Atkinson M.H., Lussier A.J., et al. The role of viscosupplementation with hylan G-F (Synvisc) in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a Canadian multicenter trial comparing hylan G-F 20 alone, hylan G-F 20 with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and NSAIDs alone. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3:213-225.

Arrich J., Prirbauer F, Mad P., Schmid D., et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2005:12, www.cmaj,ca/cgi/content/full/172/8/1039/DC1.

Brockmeier S.F., Shaffer B.S. Viscosupplementation therapy for osteoarthritis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14(3):155-162.

Chevalier X. Intraarticular treatments for osteoarthritis: new perspectives. Curr Drug Targest. 2010;11:546-560.

Conrozier T., Chevalier X. Long-term experience with hylan GF-20 in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1797-1804.

Dahlberg L., Lohmander L.S., Ryd L. Intraarticular injections of hyaluronan in patients with cartilage abnormalities and knee pain. A one-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:521-528.

Davis M.A., Ettinger W.H., Neuhaus J.M., et al. The association of knee injury and obesity with unilateral and bilateral osteoarthritis of the knee. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:278-288.

Felson D.T. An update on the pathogenesis and etiology of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(1):1-9.

Felson D.T. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. In: Brandt K.D., Doherty M., Lohmander L.S., editors. Osteoarthritis. ed 2,. Oxford: Oxford Press; 2003:9-16.

Henderson E.B., Smith E.C., Pegley F., et al. Intra-articular injections of 750 kD hyaluron in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomized single-centre double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 91 patients demonstrating lack of efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:529-534.

Lohmander L.S., Dalen N., Englund G., et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicenter Trial Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55:424-431.

Puddo G., Cipolla M., Cerullo G., et al. Arthroscopic treatment of the flexed arthritis knee in active middle-aged patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2:73-75.

Slemenda C., Brandt K.D., Heilman D.K., et al. Quadriceps weakness and osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Int Med. 1998;127:97-104.

Tepper S., Hochberg M.C. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-I). Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1081-1088.

Total knee replacement protocol

DeAndrade R.J. Activities after replacement of the hip or knee. Orthopedic special edition. 1993;2:8.

Minns-Lowe C.J., Barker K., Dewey M., et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,. 2007;335(7624):812. Epub 2007 Sep 20

Riddle D.L., Stratford P.W., Singh J.A., et al. Variation in outcome measures in hip and knee arthroplasty clinical trials: a proposed approach to achieving consensus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):2050-2056.

Roos E.M., Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 1(17), 2003. Available from http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/17

Seyler T.M., Mont M.A., Ragland P.S., et al. Sports activity after total hip and knee arthroplasty: specific recommendations concerning tennis. Sports Med. 2006;36(7):571-583.

Valtonen A., Poyhonen T., Heinonen A., et al. Muscle deficits persist after unilateral knee replacement and have implications for rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2009;89(10):1072-1079.

Wylde V., Blom A., Dieppe P., et al. Return to sport after joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90-B(7):920-923.

Cook J.R., Warren M., Ganley K.J., et al. A comprehensive joint replacement program for total knee arthroplasty: a descriptive study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [On-line]. Available with open access from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/9/154.

Healy W.L., Sharma S., Schwartz B., et al. Athletic activity after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(10):2245-2252.

Jackson J.D., Smith J., Shah J.P., et al. Golf after total knee arthroplasty: Do patients return to walking the course? Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2201-2204.

Mayer F., Dickhuth H-H. FIMS Position Statement: Physical activity after total joint replacement. International Sport Med Journal. 2008;9(1):39-43.

Milne S., Brosseau L., Robinson V., et al. Continuous passive motion following total knee arthroplasty. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2003. CD004260

Roos E.M., Roos H.P., Lohmander L.S., et al. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(2):88-96.

Total hip replacement rehabilitation: progression and restrictions

Andersen K.V., Pfeiffer-Jensen M., Haraldsted V., et al. Reduced hospital stay and narcotic consumption, and improved mobilization with local and intraarticular infiltration after hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial of an intraarticular technique versus epidural infusion in 80 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:180-186.

Becchi C., Al Malyan M., Coppini R., et al. Opioid-free analgesia by continuous psoas compartment block after total hip arthroplasty. A randomized study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:418-423.

Bertocci G.E., Munin M.C., Frost K., et al. Isokinetic performance after total hip replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:1-9.

Brander V.A., Stulberg S.D., Chang R.W. Rehabilitation following hip and knee arthroplasty. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1994;5:815-836.

Brown T.E., Cui Q., Mihalko W.M., et al. Arthritis and Arthroplasty: The Hip. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

Busch C.A., Shore B.J., Bhandari R., et al. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88-A:959.

Chandler D.R., Glousman R., Hull D., et al. Prosthetic hip range of motion and impingement. The effects of head and neck geometry. Clin Orthp Relat Res. 1982;166:284-291.

Davy D.T., Kotzar G.M., Brown R.H., et al. Telemetric force measurements across the hip and after total arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:45-50.

Deathe A.B., Hayes K.C., Winter D.A. The biomechanics of canes, crutches, and walkers. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1993;5:15-29.

Enloe L.J., Shields R.K., Smith K., et al. Total hip and knee replacement treatment programs: a report using consensus. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23:3-11.

Erickson B., Perkins M. Interdisciplinary team approach in the rehabilitation of hip and knee arthroplasties. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48:439-445.

Gilbey H.J., Ackland T.R., Wang A.W. Exercise improves early functional recovery after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;408:193-200.

Giraudet-Le Quintrec J.G., Coste J., Vastel L., et al. Positive effect of patient education for hip surgery: a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;414:112-120.

Gocen Z., Sen A., Unver B., et al. The effect of preoperative physiotherapy and education on the outcome of total hip replacement: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:353-358.

Gogia P.P., Christensen C.M., Schmidt C. Total hip replacement in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip: improvement in pain and functional status. Orthopedics. 1994;17:145-150.

Haffey W.J., Welsh J.H. Subacute care, evolution in search of value. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:SC2-SC4.

Hebl J.R., Kopp S.L., Ali M.H., et al. A comprehensive anesthesia protocol that emphasizes peripheral nerve blockade for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;88-A:63.

Holder C.G., Haskvitz E.M., Weltman A. The effects of assistive devices on the oxygen cost, cardiovascular stress, and perception of nonweight-bearing ambulation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18:537-542.

Howell J.R., Garbuz D.S., Duncan C.P. Minimally invasive hip replacement: Rationale, applied anatomy, and instrumentation. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:107-118.

Hughes K., Kuffner L., Dean B. Effect of weekend physical therapy on postoperative length of stay following total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Physiother Canada. 1993;45:245-249.

Inaba Y., Dorr L.D., Wan Z., Sirianni L., et al. Operative and patient care techniques for posterior mini-incision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:104-114.

Khan R.J.K., Haebich S., Maor D. Minimally invasive hip replacement – a randomised controlled trial. J of Bone and Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(B Supp III):405.

Kishida Y., Sugano N., Sakai T., et al. Full weight bearing after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2001;25:25-28.

Lawlor M., Humphreys P., Morrow E., et al. Comparison of early postoperative functional levels following total hip replacement using minimally invasive versus standard incisions. A prospective randomized blinded trial. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:465-474.

Lima D., Magnus R., Paprosky W.G. Team management of hip revision patients using a post-op hip orthosis. J Prosthet Orthop. 1994;6:20-24.

Maheshwari A.V., Boutary M., Yun A.G., et al. Multimodal analgesia without routine parenteral narcotics for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:231-238.

Masonis J.L., Bourne R.B. Surgical approach, abductor function, and total hip arthroplasty dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:46-53.

Möller G., Goldie I., Jonsson E. Hospital care versus home care for rehabilitation after hip replacement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1992;8:93-101.

Munin M.C., Kwoh C.K., Glynn N.W., et al. Predicting discharge outcome after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74:294-301.

O’Sullivan S.B., Schmitz T.J. Physical Rehabilitation: Assessment and Treatment, ed 2. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1988.

Pagnano M.W., Hebl J., Horlocker T. Assuring a painless total hip arthroplasty: a multimodal approach emphasizing peripheral nerve blocks. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(4 Suppl 1):80.

Palmer M.L., Toms J.E. Manual for Functional Training, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1992.

Parvataneni H.K., Shah V.P., Howard H., et al. Controlling pain after total hip and knee arthroplasty using a multimodal protocol with local periarticular injections: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):33-38.

Peak E.L., Parvizi J., Ciminiello M., Purtill J.J., et al. The role of patient restrictions in reducing the prevalence of early dislocation following total hip arthroplasty. A randomized, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:247-253.

Pellicci P.M., Bostrom M., Poss R. Posterior approach to total hip replacement using enhanced posterior soft tissue repair. Clin Orthop. 1998;355:224-228.

Peters C.L., Shirley B., Erickson J. The effect of a new multimodal perioperative anesthetic regimen on postoperative pain, side effects, rehabilitation, and length of hospital stay after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:132-138.

Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. Pain management and accelerated rehabilitation for total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:12-15.

Rao J.P., Bronstein R. Dislocations following arthroplasties of the hip: incidence, prevention, and treatment. Orthop Rev. 1991;20:261-264.

Reardon K., Galla M., Dennett X., et al. Quadriceps muscle wasting persists 5 months after total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of hip: a pilot study. Int Med J. 2001;41:7-14.

Rooks D.S., Huang J., Bierbaum B.E., et al. Effect of preoperative exercise on measures of functional status in men and women undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:700-708.

Ryu J., Saito S., Yamamoto K., et al. Factors influencing the postoperative range of motion in total knee arthroplasty. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1993;53:35.

Shih C.H., Du Y.K., Lin Y.H., et al. Muscular recovery around the hip joint after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1994;302:115-120.

Siddiqui Z.I., Cepeda M.S., Denman W., et al. Continuous lumbar plexus block provides improved analgesia with fewer side effects compared with systemic opioids after hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:393-398.

Singelyn F.J., Deyaert M., Joris D., et al. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous three-in-one block on postoperative pain and knee rehabilitation after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:88.

Soderberg G.L. Kinesiology: Applications to Pathological Motion. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1986.

Spaulding N.J. A comparative study of the effectiveness of a preoperative education programme for total hip arthroplasty patients. Br J Occup Ther. 1995;58:526-531.

Stineman M.G., Hamilton B.B., Goin J.E., et al. Functional gain and length of stay for major rehabilitation impairment categories. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;75:68-78.

Strickland E.M., Fares M., Krebs D.E., et al. In vivo acetabular contact pressures during rehabilitation, I: acute phase. Phys Ther. 1992;72:691-699.

Talbot N.J., Brown J.H., Treble N.J. Early dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: Are postoperative restrictions necessary? J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:1006-1008.

Trudelle-Jackson E., Emerson R., Smith S. Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty: a study of patients one year post surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:260-267.

Venditolli P.A., Makinen P., Drolet P., et al. A multi-modal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88-A:282.

Vukomanovi A., Popovi Z., Durovi A., et al. The effects of short-term preoperative physical therapy and education on early functional recovery of patients younger than 70 undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2008;65:291-297.

Wang A.W., Gilbey H.J., Ackland T.R. Perioperative exercise programs improve early return of ambulatory function after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:801-806.

Weingarten S., Riedinger M., Conner L., et al. Hip replacement and hip hemiarthroplasty surgery: potential opportunities to shorten lengths of hospital stay. Am J Med. 1994;97:208-213.

Whitney J.A., Parkman S. Preoperative physical activity, anesthesia and analgesia: effects on early postoperative walking after total hip replacement. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15:19-27.

Woo R.Y.G., Morrey B.F. Dislocations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1295-1306.