Chapter 6 The approach to the patient with chest pain, dyspnoea or haemoptysis

Chest pain, dyspnoea and haemoptysis are common and important symptoms which bring patients to the emergency department. The role of the emergency medical team is to rapidly identify high risk patients, commence resuscitation if necessary, arrive at an accurate diagnosis, initiate appropriate therapies and arrange appropriate disposition. Some therapies are extremely time-dependent (e.g. reperfusion therapy for myocardial infarction) and good outcomes depend on early recognition of these seriously ill patients. However, the clinician must be aware of the costs associated with inappropriate admissions and investigations.

CHEST PAIN

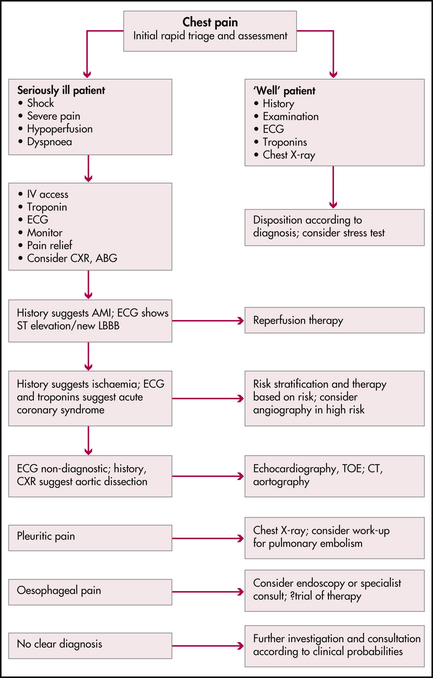

The general public is increasingly aware of the importance of chest pain and the need for early presentation with this symptom. In American emergency departments, up to 7% of all presentations are for chest pain, prompting changes in the organisation of emergency departments so that many high volume departments have specialised chest pain units where patients with this symptom are rapidly triaged and treated according to defined protocols. While there are many causes of chest pain, clinicians should be aware of disorders which are potentially life threatening (Figure 6.1). Before any chest pain patient is discharged, each of these diagnoses should at least be considered.

Myocardial ischaemia

(See also Chapter 7, ‘Acute coronary syndromes’.)

History

Take time to question the patient, using non-leading questions, to clarify the nature of the patient’s pain. The pain of myocardial ischaemia is classically a deep visceral pain felt in the anterior chest but not localised to any part of the chest. Patients may describe heaviness, constriction, a sensation like a heavy weight or a dull ache. Pain usually comes on gradually, reaching a peak over a few minutes, and lasts at least a few minutes. Patients prefer to lie still and the pain is not exacerbated by the respiratory cycle, posture or food intake. Classical radiation patterns include spread to the neck, jaw or arms. Pain radiating to the left arm is more common than to the right. Heaviness (rather than pain) in both arms is also very suggestive. Autonomic accompaniments such as sweating, nausea and anxiety are also concerning. While the pain of myocardial ischaemia may be severe, the severity of the pain is not consistently related to the extent of ischaemia. Angina usually lasts less than 20 minutes and there may be some benefit from oxygen and sublingual nitrates. The temporal pattern of angina is of prognostic significance (Table 6.1).

| Class | Description | Risk of AMI/death in next year |

|---|---|---|

| I | New onset exertional angina; angina with less effort; no rest pain | 7% |

| II | Angina at rest within the last month but no pain in last 48 hours | 10% |

| III | Angina at rest in the last 48 hours | 11% |

There may be overlap with other chest pain syndromes. Some patients describe burning pain suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux, and while sharp, stabbing or even pleuritic-type pain makes myocardial ischaemia unlikely, it does not exclude this diagnosis. Pope et al found up to 22% of patients with the principal complaint of sharp stabbing pain had an acute coronary syndrome.1,2

A number of diagnostic decision tools using history and ECG findings to assist with diagnosis have been proposed (e.g. the acute cardiac ischaemia (ACI) predictive instrument), which probably increase the accuracy of diagnosis.3 However a high index of suspicion is the most useful safeguard.

Other potentially life-threatening causes of chest pain

Pulmonary embolism

(See also Chapter 10, ‘Pulmonary emboli and venous thromboses’.)

Pleuritic pain can also be caused by pulmonary embolism, where there is a complicating pulmonary infarction and pleural irritation; however, massive pulmonary embolism can also cause central chest discomfort suggestive of angina. This is often associated with dyspnoea and haemodynamic collapse, and may reflect acute right ventricular dysfunction.

Pneumonia

Pleuritic chest pain is a common feature of respiratory tract infections which involve the pleura.

Other causes of chest pain

Abdominal disease

(See also Chapter 25, ‘Gastrointestinal emergencies’.)

Upper abdominal disorders such as cholecystitis, peptic ulcer disease and pancreatitis can be associated with chest pain which dominates the presentation and may appear out of proportion to the abdominal findings. Some of these disorders may be associated with ECG abnormalities, further confusing the diagnosis. Upper abdominal pain may be an acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Physical examination

Investigations

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

All patients complaining of chest pain should have an ECG, and previous ECGs should be obtained for comparison. If the initial ECG is unhelpful and symptoms continue, a repeat ECG in 15 minutes may be diagnostic. The ECG helps to triage patients into high, intermediate and low risk for myocardial ischaemia and is crucial in the selection of treatment. ECG patterns are discussed in detail in Chapter 12, ‘Clinical electrocardiography and arrhythmia management’.

Cardiac enzymes, markers

Rapid troponin assays (including point-of-care tests) have revolutionised the care of chest pain patients. Troponins are now considered standard of care in this clinical setting. An elevated troponin confirms the diagnosis of an acute coronary syndrome and places the patient into a higher risk group. Two normal troponin values (on admission to the emergency department and 6 hours later) are very reassuring and may allow patients to be discharged safely from the emergency department.4

Disposition

Figure 6.1 summarises an integrated approach to the work-up and disposition of the chest pain patient. A combination of symptoms, examination findings, ECG results and cardiac markers often allows a precise diagnosis in many patients. Perhaps even more importantly, the risk of adverse outcomes can be assessed. High-risk features include ongoing chest pain, an abnormal ECG and elevated troponins. These patients should be managed in a coronary care unit whereas lower risk patients might be admitted to a monitored ward bed or discharged for outpatient follow-up.

DYSPNOEA

Physical examination

The chest X-ray

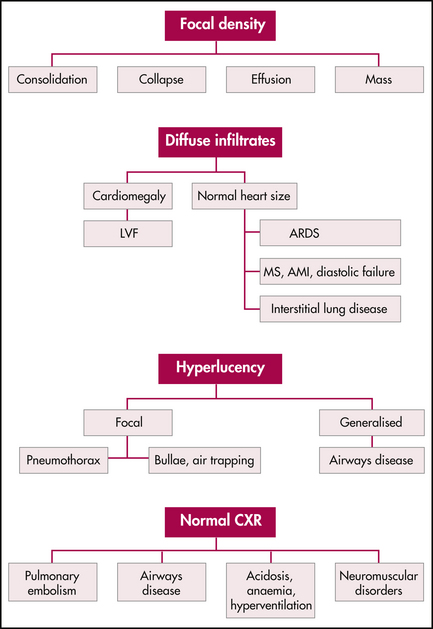

Examination of a chest X-ray is crucial in the assessment of the seriously ill patient with dyspnoea. Figure 6.2 summarises the interpretation of the chest X-ray in the breathless patient. Recall that portable chest X-ray machines have inherent technical limitations, in particular making assessment of heart size difficult.

Other tests

HAEMOPTYSIS

Most haemoptysis is minor, and should prompt a search for the cause, usually starting with a chest X-ray. In a stable patient with minor haemoptysis, investigations may be commenced in the emergency department and continued as an outpatient.

Large volume haemoptysis, defined as more than 600 mL in 24 hours,5 is life-threatening and frightening. It is often difficult for the patient to estimate the volume of blood loss. The immediate threat is not hypovolaemia, but hypoxaemia related to blood in the airways and lung parenchyma.

Causes of haemoptysis

Management of massive haemoptysis5

1 Pope J.H., Aufderheide T.P., Ruthazer R., et al. Missed diagnosis of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1163-1170.

2 Hamm C.W., Goldmann B.U., Heeschen C., et al. Emergency room triage of patients with acute chest pain by means of rapid testing for cardiac troponin T or troponin I. N Engl J Med. 1997;33:1648-1653.

3 Antman E.A. Decision making with cardiac troponin tests. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2079-2082.

4 Pope J.H., Selker H.P. Diagnosis of acute cardiac ischemia. Emerg Med Clin N America. 2003;21:27-59.

5 Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive haemoptysis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1642-1647.

Acute Coronary Syndrome Working Party. Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Med J Aust. 2006;184(8):S1-S32.

Cannon C.P., Lee T.H. Approach to the patient with chest pain. In: Libby P., Bronow R.O., et al, editors. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 8th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:1195.

Lewis W.R., Amsterdam E.A. Chest pain emergency units. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1999;14:321-328.