7 THE ANKLE AND FOOT

Applied Anatomy

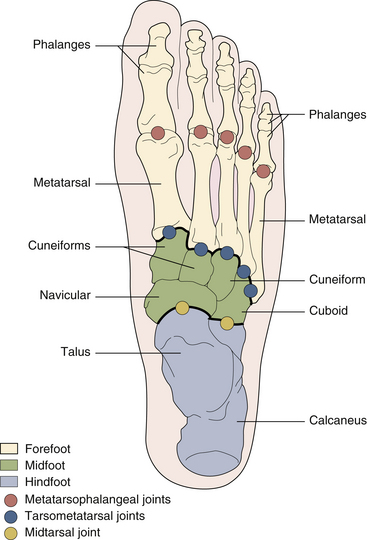

The foot can be divided into three units: the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot (Figure 7-1). The hindfoot comprises the calcaneus and talus. The anterior two thirds of the calcaneus articulates with the talus, and the posterior third forms the heel. Medially, the sustentaculum tali supports the talus and is joined to the navicular bone by the spring ligament. The talus articulates with the tibia and fibula above at the ankle joint, with the calcaneus below at the subtalar joint, and with the navicular in front at the talonavicular joint.

FIGURE 7-1 THE BONES OF THE FOOT (SUPERIOR VIEW).

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

The midfoot is made up of five tarsal bones: the navicular medially, the cuboid laterally, and the three cuneiforms distally. The midfoot is separated from the hindfoot by the midtarsal or transverse tarsal joint (talonavicular and calcaneocuboid articulations) and from the forefoot by the tarsometatarsal joints (see Figure 7-1).

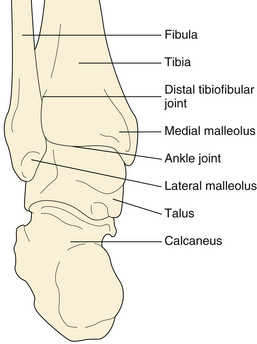

The distal tibiofibular joint is a fibrous joint (syndesmosis) between the distal tibia and the fibula (Figure 7-2). The joint allows only slight malleolar separation (< 2 mm) on full dorsiflexion of the ankle.

FIGURE 7-2 THE BONES OF THE HINDFOOT (POSTERIOR VIEW).

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

ANKLE JOINT

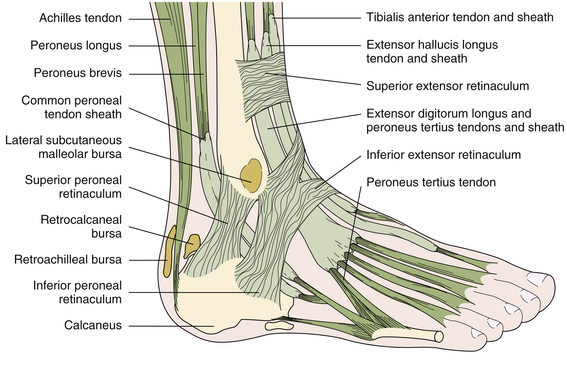

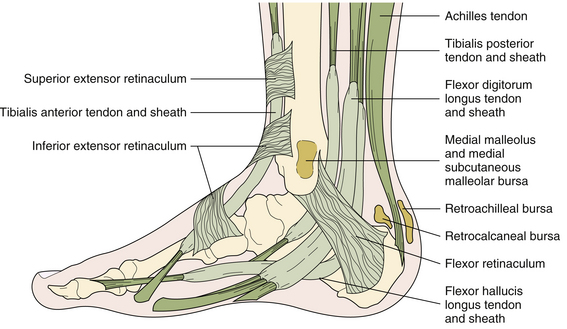

The true ankle (talocrural) joint is a saddle-shaped hinge joint between the distal ends of the tibia and fibula and the trochlea of the talus (see Figure 7-2). Most of the body weight is transmitted through the tibia to the talus. The medial (tibial) malleolus and the lateral (fibular) malleolus extend distally to form the ankle mortise that stabilizes the talus and prevents rotation. The joint capsule is lax anteriorly and posteriorly but is strengthened medially by the powerful deltoid ligament and laterally by three distinct bands: the anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments and the calcaneofibular ligament. The synovial cavity does not normally communicate with other joints, adjacent tendon sheaths, or bursae. Tendons crossing the ankle region are invested for part of their course in tenosynovial sheaths (Figures 7-3 and 7-4).

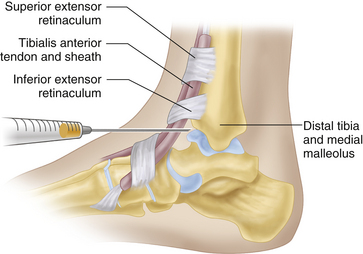

In the anterior (extensor) compartment, the tendons of the tibialis anterior (most medial), extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and peroneus tertius (most lateral) muscles are bound down by the superior and inferior extensor retinaculi (see Figure 7-3). The dorsalis pedis artery runs between the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus tendons.

In the lateral (peroneal) compartment, the peroneus longus and brevis tendons are enclosed in a single synovial sheath that runs behind and below the lateral malleolus (see Figure 7-3). The superior and inferior peroneal retinaculi strap down the peroneal tendons.

In the medial (flexor) compartment, the tendons of the tibialis posterior (most medial), flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus (most lateral) muscles are held down by the flexor retinaculum, forming the tarsal tunnel (see Figure 7-4). The flexor retinaculum bridges the interval between the medial malleolus and the calcaneus. The posterior tibial artery and nerve lie between the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus and the flexor hallucis longus.

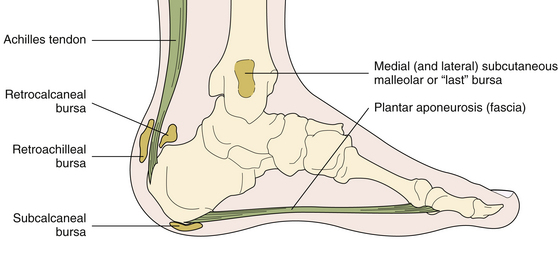

FIGURE 7-4 BURSAE, TENDONS, AND TENDON SHEATHS OF THE MEDIAL (FLEXOR) COMPARTMENT OF THE ANKLE.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

Several bursae exist around the ankle (Figure 7-5; also see Figures 7-3 and 7-4). The retrocalcaneal bursa, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and the posterior surface of the calcaneus, is surrounded anteriorly by Kager’s fat pad. The bursa serves to protect the distal Achilles tendon from frictional wear against the posterior calcaneus. The retroachilleal bursa lies between the skin and the Achilles tendon and protects the tendon from external pressure. The subcalcaneal bursa lies beneath the skin over the plantar aspect of the calcaneus. The medial and lateral subcutaneous malleolar, or “last” bursae, are located near the medial and lateral malleoli, respectively.

FIGURE 7-5 BURSAE AROUND THE ANKLE.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

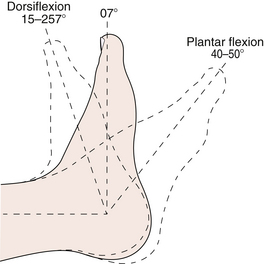

Movements of the ankle include dorsiflexion and plantar flexion (Figure 7-6). The axis of movement passes approximately through the malleoli. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles are the prime plantar flexors of the ankle. The tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus muscles are the prime dorsiflexors.

MIDTARSAL JOINT

The midtarsal (transverse tarsal) joint comprises the combined talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints (see Figure 7-1). The cuboid and navicular are usually joined by fibrous tissue, but a synovial cavity may exist. The midtarsal joint contributes to inversion (supination) and eversion (pronation) movements at the subtalar joint. It also allows 20° of adduction (foot turned toward the midline) and 10° of abduction (foot turned away from the midline). The axis of rotation of the subtalar and midtarsal joints is such that inversion is invariably accompanied by adduction of the forefoot, called supination, and eversion by abduction of the forefoot, called pronation. The tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior, aided by the gastrocnemius, invert the foot. The peroneus longus, peroneus brevis, and extensor digitorum longus evert the foot, aided by the peroneus tertius.

The intertarsal joints between the navicular, cuneiforms, and cuboid are plane-gliding joints that intercommunicate with one another and with the intermetatarsal and tarsometatarsal joints (see Figure 7-1).

METATARSOPHALANGEAL JOINTS

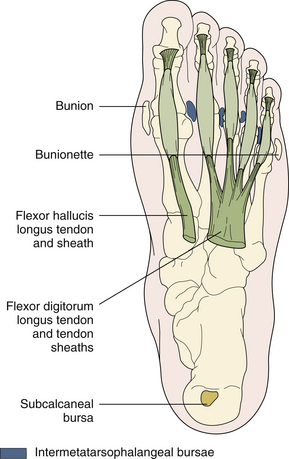

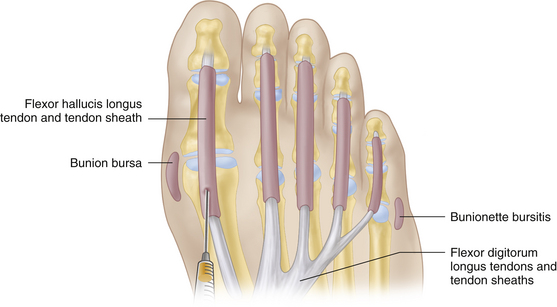

The metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints are ellipsoid synovial joints that lie about 2 cm proximal to the webs of the toes. Their capsule is strengthened by the collateral ligaments on each side and by the plantar ligament (plate) on the plantar surface. The plantar ligaments are fused with the flexor tendon sheaths and are connected together by the transverse metatarsal ligament, which holds the metatarsal heads together to prevent excessive splaying of the forefoot. Small intermetatarsophalangeal bursae are frequently present between the metatarsal heads (Figure 7-7). The long extensor tendons form the extensor expansions (aponeuroses), which overlay the dorsum of the MTP joints and digits. The intrinsic muscles of the foot—including the flexor hallucis brevis, the lumbricals, the interossei, and the flexor digiti minimi brevis—are partly inserted into the extensor expansions and assist in plantar flexion of the MTP joints. The extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor digitorum brevis dorsiflex the MTP joints. Movements at the first MTP joint consist of dorsiflexion (70° to 90°) and plantar flexion (about 35° to 50°). The other MTP joints permit about 40° dorsiflexion and 40° plantar flexion, as well as a few degrees of abduction (away from the second toe) and adduction (toward the second toe).

INTERPHALANGEAL JOINTS

The proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are hinge joints. The plantar flexors are the flexor hallucis longus and brevis (great toe), the flexor digitorum longus (the lateral four toes at the DIP joints), and the flexor digitorum brevis (the lateral four toes at the PIP joints). The dorsiflexors are the extensor hallucis longus and the extensor digitorum longus and brevis, assisted by the interossei and lumbricals. The digital flexor tendon sheaths enclose the long and short flexor tendons, extending along the length of the toes to the distal third of the sole proximally (see Figure 7-7). A bunion bursa is commonly located over the medial aspect of the first MTP joint. Less frequently, a bursa is present over the fifth metatarsal head (bunionette or tailor’s bunion or bursa; see Figure 7-7).

ARCHES OF THE FOOT

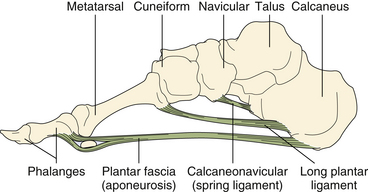

The arches of the foot are the result of the intrinsic mechanical arrangement of the bones supported by ligaments and intrinsic and extrinsic muscles, particularly the tibialis posterior and anterior muscles. The arches of the foot act as shock absorbers during weight bearing. Each foot has two longitudinal and two transverse arches (Figure 7-8). The medial longitudinal arch is high and flexible and comprises the medial three rays digits—cuneiforms, navicular, and talus—and the calcaneus. It provides a resilient spring for weight bearing and forward propulsion in walking. The lateral two rays, cuboid and calcaneus, constitute the low, more rigid lateral longitudinal arch. The anterior transverse metatarsal arch includes the second, third, and fourth metatarsals and the heads of the first and fifth metatarsals. It becomes flattened on weight bearing but returns to its arched position when the weight is removed. The transverse midtarsal arch is more rigid and lies across the midtarsal region.

FIGURE 7-8 THE FOOT: MEDIAL LONGITUDINAL ARCH AND LIGAMENTS.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

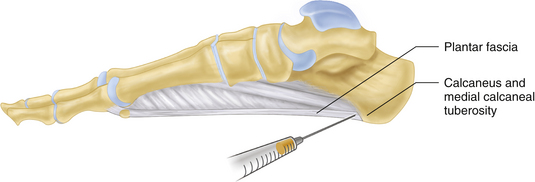

The longitudinal arches are held together by several layers of ligaments: the spring (calcaneonavicular) ligament; the long and short plantar ligaments that join the calcaneus to the metatarsal bases; and, most superficially, the plantar fascia (aponeurosis; see Figure 7-8). The plantar fascia extends anteriorly from the medial calcaneal tuberosity and splits at about the middle of the sole into five bands, one for each toe, to be attached to the transverse metatarsal ligament, the flexor tendon sheaths of the toes, and the proximal phalanges. The plantar fascia acts as a strong mechanical tie for the longitudinal arches by joining the three main weight-bearing points of the foot: the calcaneus, the first metatarsal head (including the two sesamoids), and the fifth metatarsal heads. During “toe off” in the later portion of stance phase, it helps the arch to reform and the foot to become more rigid.

Differential Diagnosis of Ankle and Foot Pain

Ankle and foot pain may arise from bones, joints, periarticular soft tissues, plantar fascia, tendon sheaths, bursae, skin and subcutaneous tissue, nerve roots, peripheral nerves, or the peripheral vascular system, or it may be referred from the lumbar spine or knee joint. Static disorders caused by inappropriate footwear, foot deformities, or weak intrinsic muscles account for the vast majority of painful foot conditions. Table 7-1 describes the differential diagnosis of ankle and foot pain.

| Articular | |

| Arthritis | RA, OA, PsA, gout |

| Toe disorders | Hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, hammer toe |

| Arch disorders | Pes planus, pes cavus |

| Periarticular | |

| Cutaneous | Corn, callosity |

| Subcutaneous | RA nodules, tophi |

| Ingrowing toenail | |

| Plantar fascia | Plantar fasciitis |

| Plantar nodular fibromatosis | |

| Tendons | Achilles tendinitis |

| Achilles tendon rupture | |

| Tibialis posterior tenosynovitis | |

| Peroneal tenosynovitis | |

| Bursae | Bunion, bunionette |

| Retrocalcaneal, retroachilleal, and subcalcaneal bursitis | |

| Medial and lateral malleolar bursitis | |

| Acute calcific periarthritis | Hydroxyapatite pseudopodagra (first MTP) |

| Osseous | |

| Fracture (traumatic, stress) | |

| Sesamoiditis | |

| Neoplasm | |

| Infection | |

| Epiphysitis (osteochondritis) | Second metatarsal head (Freiberg disease) |

| Navicular (Köhler disease) | |

| Calcaneus (Sever disease) | |

| Painful accessory ossicles | Accessory navicular |

| Os trigonum (near talus) | |

| Os intermetatarseum (first and second) | |

| Neurologic | |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome | |

| Interdigital (Morton) neuroma | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

| Radiculopathy (lumbar disk) | |

| Vascular | |

| Ischemic | Atherosclerosis, Buerger disease |

| Vasospastic disorder (Raynaud disease) | |

| Cholesterol emboli with “purple toes” | |

| Referred | |

| Lumbosacral spine | |

| Knee | |

| Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome |

MTP, metatarsophalangeal; OA, osteoarthritis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Specific Disorders of the Ankleand Foot Region

ACHILLES TENDINITIS

Achilles tendinitis usually is caused by repetitive trauma and tendon microtears due to excessive use of the calf muscles, as occurs in ballet dancing; track and field, including distance running and jumping; or from faulty footwear with a rigid shoe counter. Enthesopathy and insertional Achilles tendinitis may also occur in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The tendon is a common site for gouty tophi, rheumatoid nodules, and xanthomas.

PAINFUL ANKLE DISORDERS

Ankle pain is a common patient complaint caused by a number of MSK disorders. Pathology in the bones, joints, ligaments, or tendons can all be accountable for pain and swelling in the region. The differential diagnosis can be narrowed by identifying the most affected side (medial versus lateral), by history, and on physical exam (Table 7-2).

| Lateral Ankle Pain |

| Peroneal tendon injury/subluxation |

| Ligamentous injury (anterior and posterior talofibular ligament, calcaneofibular ligament) |

| High ankle (syndesmotic) sprain (anteroinferior tibial fibular ligament) |

| Fracture (talus, distal fibular, Jones) |

| Fibular or sural nerve irritation |

| Achilles tendon injury |

| Subtalar joint ligament injury |

| Medial Ankle Pain |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome |

| Posterior tibial tendinitis |

| Ligamentous injury (anterior/posterior tibiotalar, tibionavicular, tibiocalcaneal) |

| Subtalar joint arthropathy |

| Medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) |

| Malleolar fractures |

PAINFUL HEEL DISORDERS

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of subcalcaneal heel pain (Table 7-3). It results from repetitive microtrauma, which causes microtears of the plantar fascia at its attachment into the medial calcaneal tuberosity. Risk factors include repetitive trauma from athletic activities, occupations that entail excessive standing and walking (e.g., “policeman’s heel”), changes in footwear, reduced ankle dorsiflexion (< 10°), obesity, and pronated everted flat foot (pes planovalgus). It may also occur as an enthesopathy in association with AS or PsA.

| Posterior Heel Pain |

| Achilles tendinitis |

| Achilles tendon rupture |

| Achilles bursitis: retrocalcaneal and retroachilleal |

| Achilles enthesitis (enthesopathy: AS, PsA) |

| Subtalar arthritis |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome |

| Painful dorsal calcaneal spur (rare) |

| Plantar (Subcalcaneal) Heel Pain |

| Plantar fasciitis |

| Subcalcaneal bursitis |

| Painful calcaneal fat pad |

| Bone (calcaneal) lesions |

| Fracture (traumatic, stress) |

| Epiphysitis (Sever disease) |

| Neoplasm |

| Infection |

| Painful plantar calcaneal spur (rare) |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis

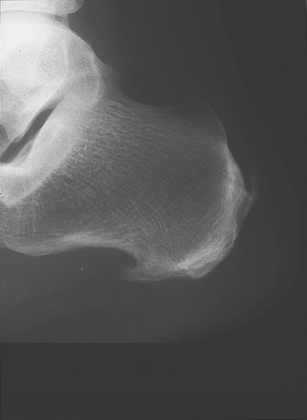

Bilateral plantar and calcaneal traction spurs are common in obese, stout, middle-aged and elderly individuals (Figure 7-9). Traction spurs are frequently asymptomatic, although heel pain may result from a coexistent plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis, or painful heel pad.

FIGURE 7-9 PLANTAR CALCANEAL SPUR.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

Metatarsalgia and Morton Interdigital Neuroma

Metatarsalgia, or pain and tenderness in and about the metatarsal heads or MTP joints, is a common symptom with diverse causes (see Table 7-3). It often appears after years of misuse and weakness of the intrinsic muscles due to chronic foot strain from improper footwear, with the toes cramped into tight or pointed shoes. Pain in the forefoot on standing or walking and tenderness of the metatarsal heads and MTP joints are the main clinical findings. Plantar calluses and clawed toes are frequently present (Table 7-4).

| Chronic foot strain from improper footwear |

| Altered foot biomechanics: flat, cavus, or splay foot |

| Overlapping and underlapping toes |

| Interdigital (Morton) neuroma |

| Attrition of the plantar fat pad in elderly patients |

| Painful plantar callosities, including intractable plantar keratosis |

| Plantar plate rupture with secondary MTP joint instability (usually the second) |

| Hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, hammer and mallet toes |

| Arthritis of the MTP joints: OA, RA, PsA, gout, trauma |

| Bunion, bunionette, and intermetatarsophalangeal bursitis |

| Osteochondritis of the second metatarsal head (Freiberg disease) |

| Metatarsal stress (march) fracture |

| Sesamoiditis, sesamoid fracture, or osteonecrosis |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome, neuropathy |

| Ischemic forefoot pain: peripheral vascular disease, vasospastic disorders (Raynaud disease) |

| Failed forefoot surgery |

MTP, metatarsophalangeal; OA, osteoarthritis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Hallux Limitus and Hallux Rigidus

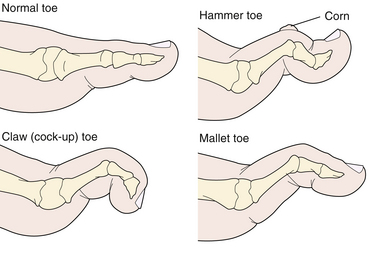

Hammer toe deformity most commonly affects the second toe. It is characterized by flexion deformity of the PIP joint, associated with dorsiflexion of the MTP and DIP joints (see Figure 7-11). A painful corn often develops over the dorsal prominence of the PIP joint. Leading causes include ill-fitting footwear—particularly narrow, high-heeled, pointed shoes—trauma, and RA, and it may also be a congenital deformity.

Systemic Arthropathies Affecting the Ankle and Foot

SPECIFIC DISORDERS OF THE ANKLE AND FOOT

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot (the most common site). Poor control will lead to joint destruction and deformities. Of particular concern is a rupture of the tibialis posterior tendon, which results in a collapsed midfoot with forefoot abduction and hindfoot valgus.

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

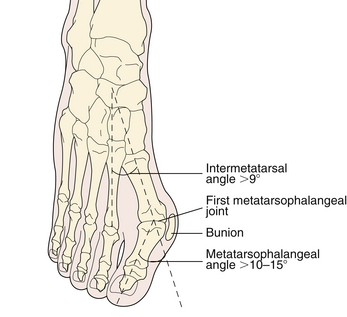

The toes are simple extensions of the metatarsals. The first and fifth toes are often slightly deviated toward the middle of the forefoot. Hallux valgus deformity refers to a lateral deviation of the first (great) toe on the first metatarsal greater than 10° to 15° (Figure 7-10). Straightening or medial deviation of the great toe on the first metatarsal is called hallux varus, and hallux limitus refers to painful limitation of dorsiflexion of the first MTP joint. In hallux rigidus, there is marked limitation of movement or immobility of the first MTP joint, usually caused by advanced osteoarthritis (OA). Cock-up or claw toe deformity refers to dorsiflexion of the MTP joint and plantar flexion of both the PIP and DIP joints (Figure 7-11). Hammer toe refers to plantar flexion deformity of the PIP joint, usually associated with dorsiflexion of the MTP and DIP joints (see Figure 7-11). In mallet toe deformity, either the DIP joint is plantar flexed and the PIP joint is neutral, or the PIP joint is plantar flexed and the DIP joint is neutral. It is usually associated with a dorsiflexed MTP joint (see Figure 7-11).

PALPATION

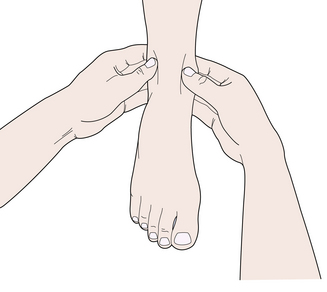

The ankle joint is palpated with the foot in slight plantar flexion. The joint is supported by the fingers of both hands, while the thumbs firmly palpate the anterior aspect of the joint (Figure 7-12). The capsule and synovial membrane are best palpated over the joint line, just distal to the lower end of the tibia and medial to the tibialis anterior tendon. The margins of a swollen synovium in other locations may be difficult to outline because of the overlying tendons. A large ankle effusion may bulge both medial and lateral to the extensor tendons and produce fluctuance: pressure with one hand on one side of the joint causes a fluid wave to be transmitted to the hand on the other side of the joint. Ankle tenosynovitis produces a superficial, linear, tender swelling that extends beyond the joint margins. The swelling is made more prominent by tightening of the involved tendon. Distension of the lateral and medial “last” bursae produces a localized, oval swelling over the anterolateral and anteromedial aspects of the joint, respectively.

FIGURE 7-12 PALPATION OF THE ANKLE JOINT.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

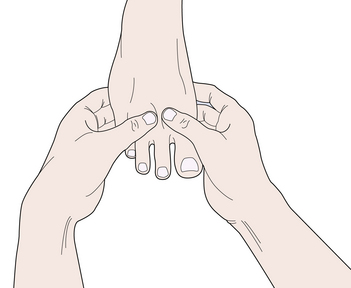

The midtarsal, intertarsal, and tarsometatarsal joints are palpated by using the thumbs on the dorsal surface, while the fingers support the plantar aspect of the foot. Tenderness of the MTP joints can be assessed by gentle compression of the metatarsal heads together with one hand (metatarsal compression test). Each joint is then palpated separately for tenderness or evidence of synovial thickening, using the thumbs over the dorsal surface and the forefingers over the plantar aspect (Figure 7-13). Chronic synovitis of the MTP joints often results in toe deformities, loss of the normal plantar fat pad under the metatarsal heads, callus formation, and forefoot (metatarsal) spread due to weakening of the transverse metatarsal ligament. The interphalangeal joints of the toes are palpated for tenderness, synovial thickening, or effusion using the thumbs and forefingers of both hands.

RANGE OF MOTION

Ankle movements are tested with the knee flexed. The normal range is 15° to 25° of dorsiflexion from the neutral position, with the foot at a right angle to leg, and 40° to 50° of plantar flexion (see Figure 7-6).

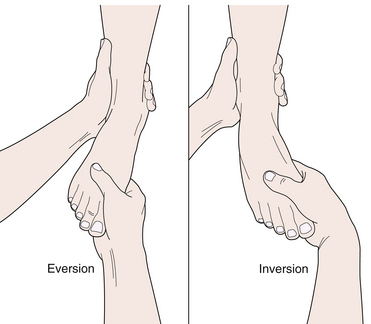

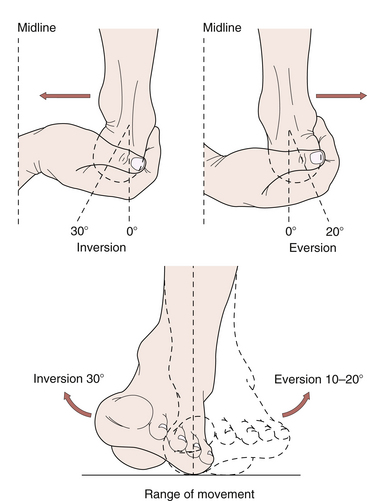

Subtalar movements are examined with the ankle in the neutral position. The heel is grasped with one hand, while the other hand stabilizes the distal leg (Figure 7-14). The heel is then turned inward (inversion) to 30° and outward (eversion) to 20°.

FIGURE 7-14 SUBTALAR JOINT: EXAMINATION AND RANGE OF MOVEMENTS.

(From Hochberg H, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al., eds. Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby, 2003.)

To test movements of the midtarsal joint, the talus and calcaneus are stabilized with one hand, while the other hand rotates the forefoot inward (inversion) to 30° and outward (eversion) to 20° (Figure 7-15).

SPECIAL MANEUVERS

In tarsal tunnel syndrome, the Tinel sign is positive if percussion of the posterior tibial nerve—found immediately behind the posterior tibial artery at the flexor retinaculum, behind the flexor digitorum longus tendon—produces paresthesia in the distribution of one or more of its two branches (the medial and lateral plantar nerves). Similar symptoms can sometimes be induced by simple pressure on the nerve beneath the flexor retinaculum. Inflating a sphygmomanometer cuff around the leg to produce venous congestion may also reproduce the paresthesia (positive tourniquet test). In anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, the deep peroneal nerve, which travels with the dorsalis pedis artery, is entrapped under the extensor retinaculum, and the Tinel sign is often positive.

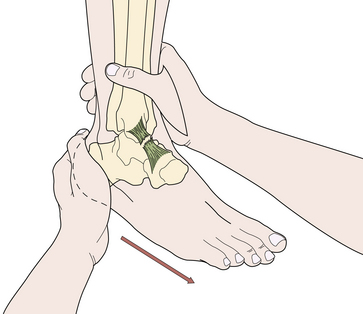

Inversion and eversion sprains of the ankle can result in tears of the lateral and medial ligaments, respectively. Inversion sprains are more common and result in a tear of the lateral ligament, particularly its anterior talofibular band. To test the ligament, the distal tibia and fibula are held in one hand, while the calcaneus and talus are drawn forward by the other hand (Figure 7-16). A major tear of the anterior talofibular ligament allows forward movement of the talus on the tibia (positive anterior drawer sign).

Injections of the Ankle and Foot

The ankle joint can be injected via an anteromedial approach with the joint slightly plantar flexed. The needle is inserted at a point just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon and distal to the lower margin of the tibia. The needle is directed posteriorly and laterally to a depth of about 1 to 2 cm (Figure 7-17).

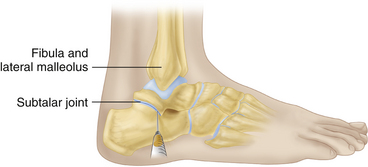

For injection of the subtalar joint, the patient lies supine with the leg–foot angle at 90°. The needle is inserted horizontally into the subtalar joint, just inferior to the tip of the lateral malleolus at a point just proximal to the sinus tarsi (the depression between the lateral talus and the calcaneus, in which lies the extensor digitorum brevis; Figure 7-18). Injection of the other intertarsal and the tarsometatarsal joints often requires fluoroscopic or computed tomographic (CT) guidance.

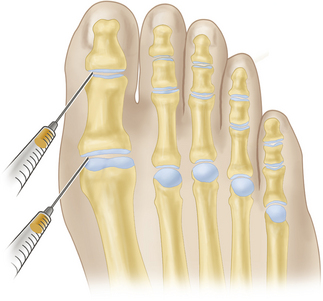

The metatarsophalangeal joint can be entered via a dorsomedial or dorsolateral route (Figure 7-19). The joint space is first identified, and then a 27 gauge needle is inserted on either side of the extensor tendon to a depth of 2 to 4 mm. Slight traction on the toe facilitates entry. The toe PIP and DIP joints may be entered in a similar fashion via a dorsomedial or dorsolateral route.

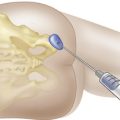

For injection of plantar fasciitis, the patient lies supine, and the point of maximal tenderness under the heel is marked. After infiltration with 1% lidocaine, the needle is inserted through the thinner skin of the medial side of the heel and advanced, in a lateral and slightly upward and posterior direction, toward the medial calcaneal tuberosity (Figure 7-20). The injection is made as close as possible to the plantar surface of the calcaneus. If the bone is struck, the needle is withdrawn slightly before the corticosteroid-lidocaine mixture is injected.

For injection of the toe flexor digital tendon sheath, the patient lies supine, and a 27 gauge needle is inserted tangentially into the center of the flexor digital sheath, opposite the plantar surface of the metatarsal head (Figure 7-21). The needle is advanced slowly until gentle passive movements of the toe makes a crepitant sensation, indicating that the needle tip is rubbing against the surface of the tendon. When this occurs, the needle is withdrawn 0.5 to 1.0 mm before the corticosteroid is injected.

Bottger B.A., Schweitzer M.E., El-Noueam K., Desai M. MR imaging of the normal and abnormal retrocalcaneal bursae. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1998;170:1239-1241.

Fam A.G. The ankle and foot. In: Hochberg H., Silman A.J., Smolen J.S., et al, editors. Rheumatology. third ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby; 2003:681-692.

Gould J.S. Metatarsalgia. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1989;20:553-562.

Maffulli N. Rupture of the Achilles tendon. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1999;81:1019-1035.

Mazzone M.F., McCue T. Common conditions of the Achilles tendon. Am. Fam. Physician. 2002;65:1805-1810.

Perry J. Anatomy and biomechanics of the hindfoot. Clin. Orthop.. 1983;177:9-15.

Riddle D.L., Pulisic M., Pidcoe P., Johnson R.E. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: A matched case-control study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 2003;85:872-877.

Schepsis A.A., Leach R.E., Gorzyca J. Plantar fasciitis: Etiology, treatment, surgical results and review of the literature. Clin. Orthop.. 1991;266:185-196.

Stephens M.M. Haglund’s deformity and retrocalcaneal bursitis. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1994;25:41-46.

Wu K.K. Morton neuroma and metatarsalgia. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol.. 2000;12:131-142.