Chapter 23

The Acutely Ill or Injured Patient1

There is no thing more precious here than tyme.

Saint Bernard (1090–1153)

The objective of this chapter is to provide a practical approach to acutely ill and injured patients. The emphasis is on a prioritized assessment and diagnostic considerations, not on therapy. The chapter is for those who care for patients outside of traditional medical settings and those who provide care in traditional health care environments such as clinics, doctors’s offices, and hospitals.

In the assessment of acutely ill and injured patients, time can be a critical factor. Developing an organized, structured approach to rapidly assess the critically ill and injured patient is important to beginning the correct lifesaving therapies and identifying the proper resources and environment to take ideal care of the patient.

In contrast to the assessment of stable patients, the evaluation of acutely ill patients involves the rapid, systematic identification of pathophysiologic abnormalities that may require the initiation of lifesaving therapies while the final diagnosis is under investigation. Many causes of acute illness may have overlapping signs and symptoms that require investigation to discover the root cause, but therapy must begin to prevent further harm or death to the patient.

In the evaluation of acutely ill patients, it is always helpful to ask yourself, “What is the most serious threat to life, and have I begun to stabilize it as much as possible?”, followed by asking, “What is the most likely cause and what have I ruled out so far?”

Personal Safety

No discussion of caring for the acutely ill and injured would be complete without a reminder to health care providers to look out for their own personal safety and wellness as an initial priority. In caring for an acutely ill or injured patient, there are high risks for exposure to body fluids. Standard precautions should be taken to minimize the possibility for contamination and exposure at all times. The potential for concern should be evaluated to determine the appropriate level of precautions needed. Wearing protective gloves is certainly considered a minimum step, but as the potential for contamination escalates, consideration should be given to masks with eye shields, protective gowns, and so on.

The safety of the care environment should always be a primary consideration. Having adequate police, security, or additional personnel to ensure that the environment is safe for the health care providers is paramount. Although this is especially true in the prehospital care environment, it must also be thought about in the hospital.

As you approach the apparent patient, always perform a brief evaluation to determine whether you are in a safe environment; if not, protect yourself and your patient to limit exposure to possible injury. Assess environmental hazards; the potential of agitation from a delirious patient, causing aggressive action; and other personnel hazards such as family members and bystanders.

While uncommon, if the situation exists in which it is likely that the rescuer(s) could be injured or killed while rendering care, the rescuer should wait until the situation can be made safe. For example, in an automobile accident, a patient trapped in a car in a busy traffic lane should not be given first aid until safety flares or cones can be placed to prevent secondary accidents. Other hazards, such as downed power lines, should be investigated as well.

When providing care in the field, is also important to assess the situation to determine what further resources may be needed to ideally care for the patient(s). Identifying the situation of the patient at the scene may help determine the mechanisms of injury to assist in the diagnostic workup and in treatment for the patient.

The initial task for the health care provider in approaching most, if not all, patients in acute situations involving an unconscious patient is to first ascertain that they are not in cardiopulmonary arrest. If so, summoning help and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are the initial priorities. If the patient is not in need of CPR, immediate identification of the causes of their non-responsiveness should be initiated through an organized two-step approach to the rapid patient assessment, which includes a primary survey and secondary survey. This organized approach helps to lend a prioritization to the approach to ensure the major threats to life are identified first. The acceptable approach to these acute, undefined encounters is to consider the patient unstable until you can confirm, through a series of diagnostic steps, that the patient is well enough for you to take the time to perform a more rigorous and complete physical examination and document a complete history.

Current Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines

For the unconscious patients who are determined to be in cardiac arrest, the health care provider should initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation according to the guidelines set by the American Heart Association (AHA).

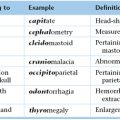

For more than 40 years, emergency teams have always practiced the A-B-C (airway, breathing, chest compression) sequence for resuscitation. In October 2010, the AHA, after many years of research, recommended that the three steps of CPR and emergency cardiac care (ECC) be rearranged. The newest development in the 2010 AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC was a change in the basic life support (BLS) sequence of steps from “A-B-C” (airway, breathing, chest compressions) to “C-A-B” (chest compressions, airway, breathing) for adults and pediatric patients (children and infants, excluding newborns). Figure 23-1 shows the new recommendation.

Figure 23–1 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation survey algorithm. Courtesy of the American Heart Association.

Chest compressions provide blood flow to the heart and brain during a cardiac arrest, and research has shown that delays or interruptions to compressions reduced survival rates. Ventilations are less critical, as victims will have oxygen remaining in their lungs and bloodstream for the first few minutes after a cardiac arrest. Starting CPR with chest compressions can effectively circulate blood to the victim’s brain and heart sooner, with the principal goal of maintaining some amount of oxygenated blood circulating through the brain.

In the original A-B-C sequence, chest compressions were often delayed while the responder opened the airway to give mouth-to-mouth breaths or retrieved a barrier device or other ventilation equipment. By changing the sequence to C-A-B, chest compressions can be initiated sooner and ventilation only minimally delayed until completion of the first cycle of chest compressions (30 compressions should be accomplished in approximately 18 seconds).

C-A-B

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Survey

It should not be assumed that any patient who is not obviously interacting with his or her environment is simply sleeping. For the purpose of this approach, the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest until it is proved otherwise. As you approach the patient, observe the patient closely, looking for spontaneous breathing or movements. If these are not discernible, stimulate the patient by talking loudly to him or her and gently shaking them while asking, “Are you okay?”

If there is no response or evidence of spontaneous breathing, call for help in any way you can without leaving the patient; it is unlikely that you can manage the entire resuscitation by yourself.

Determine whether there is spontaneous cardiac function by feeling for a carotid pulse for 10 seconds or, in an infant, by palpating the arm for a brachial artery impulse. If there is no pulse, begin external chest compressions, at least 100 per minute.

To open an unconscious victim’s airway, hyperextend the head and lift the patient’s chin; place one hand on the patient’s forehead and the other behind the patient’s occiput, and tilt his or her head backward. This maneuver moves the tongue away from the back of the throat, allowing air to pass around the tongue and into the trachea. Caution should be exercised with any patient who has a suspected neck injury. With such a patient, try to open the airway by lifting the chin and jaw without tilting the head backward; grasp the lower teeth and pull the mandible forward. If necessary, tilt the head back very slightly. If a patient is wearing dentures, remove them only if they occlude the airway.

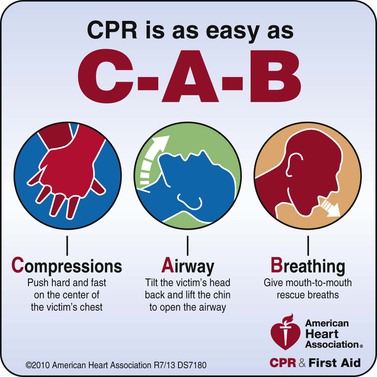

Summary of CPR Guidelines for Adults, Children, and Infants

Check

CPR

• Push chest at least 2 inches, 30 times in the center of the chest

▪ Push 2-handed, with one hand on top of the other

• Push at a rate of at least 100 pushes per minute

• Allow complete chest recoil after each push

• Limit interruptions in chest pushes to less than 10 seconds

• BREATHE

• Head Tilt–Chin Lift: tilt the head back and lift the chin

• Give 2 breaths. Give each breath over 1 second

Continue Sets of 30 Pushes and 2 Breaths

• Continue compressions and breaths—30 compressions, two breaths—until help arrives.

• CPR ratio for one-person CPR is 30 pushes to 2 breaths

• CPR ratio for two-person CPR is 15 pushes to 2 breaths

• In two-person CPR the rescuers should change positions after every 2 minutes

Figure 23-2 is a summary of these key basic life support components for adults, children, and infants (excluding newborn infants).

Figure 23–2 Summary of key basic life support components for adults, children, and infants. From American Heart Association, Hazinski, MF, Chameides L, et al: Highlights of the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for CPR and ECC. Available at: http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@ecc/documents/downloadable/ucm_317350.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2013.

There is continued emphasis on providing high-quality chest compressions. Remember to:

The new recommendation also states that the chest should be depressed at least 2 inches, as opposed to approximately  to 2 inches, which was the recommendation in 2005.

to 2 inches, which was the recommendation in 2005.

There has been no change in the recommendation for a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 30 : 2 for single rescuers of adults, children, and infants (excluding newborn infants). The 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR continue to recommend that rescue breaths be given in approximately 1 second. Once an advanced airway is in place, chest compressions can be continuous (at a rate of at least 100/min) and no longer cycled with ventilations. Rescue breaths can then be provided at about 1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds (about 8 to 10 breaths per minute). Excessive ventilation should be avoided.

Assessment of the Acutely Ill or Injured Patient

The assessment of the acutely ill patient involves moving through a series of simple evaluations, which are grouped into two categories termed the primary and secondary surveys. The primary survey is a check for conditions that are an immediate threat to the patient’s life. This initial assessment should take no longer than 10 to 15 seconds. The primary survey is subdivided into a cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) survey and a key vital functions assessment. The secondary survey is a check for conditions that could become life-threatening problems if not recognized and attended to.

The primary and secondary surveys are used for both adult and pediatric patients, as well as for medical and injury-related problems. The treatment process is integrated into the diagnostic process. For example, if the patient is not breathing, ventilations are begun immediately, before you move on to the next diagnostic step.

The first task is to recognize when a patient is acutely ill. An unusual appearance or behavior may be the only sign. These include breathing difficulties, clutching the chest or throat, slurring of speech, confusion, unusual odor to the breath, sweating for no apparent reason, or uncharacteristic skin color (e.g. pale, flushed, or bluish).

Remember that an acutely ill patient is anxious and frightened; a calm and reassuring voice can go a long way toward comforting the patient. It is always easier to care for a relaxed patient than for an anxious one.

Primary Survey

Key Vital Functions Assessment Survey

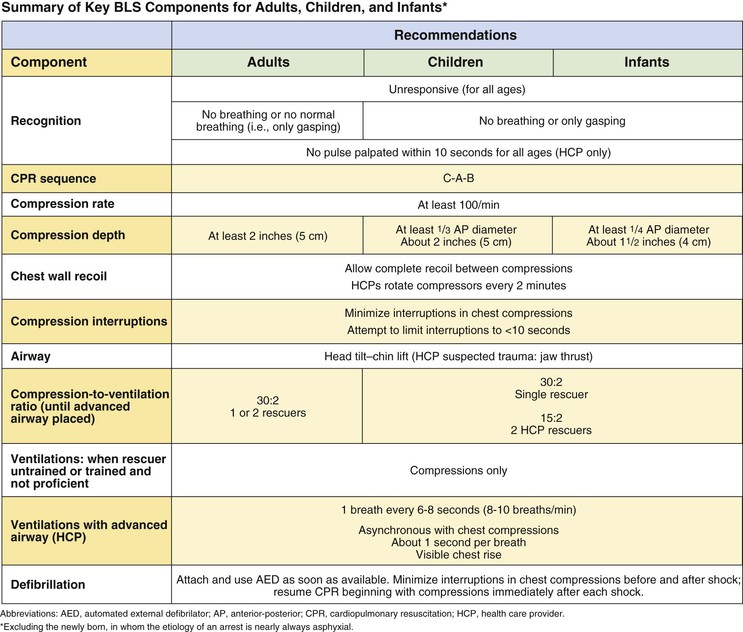

Figure 23-3 illustrates the Key Vital Functions Algorithm. Once it has been determined that the patient does not need CPR or the patient has recovered spontaneous cardiopulmonary activity, ascertain whether key life-sustaining functions are adequate and stable or whether augmentation or other supportive measures are necessary.

Figure 23–3 Key vital functions assessment algorithm.

The primary or initial survey developed by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) for the Advanced Trauma Life Support Guidelines is an excellent starting point for an organized rapid assessment to identify and begin treatment for potentially critically injured trauma patients and it also works well for acute illness.

It uses a familiar pneumonic, that being ABCDE for the Initial or Primary Survey. During the evaluation of the Primary Survey it is important to remember that if you find a significant problem you should began to initiate treatment before moving on if possible.

A–Airway

Assessment of airway begins by assessing if the patient has a patent airway. This can be accomplished by observing if the patient has any obvious obstruction to the airway. This can often easily be accomplished by asking the patient what their name is. If they can speak, the airway is open. When assessing the airway one should observe for obstructions, potential obstructions and the associated signs and symptoms. Always keep in mind that the most common cause of a obstruction in the unconscious patient is the patient’s own tongue. If the patient has no suspicion of neck injury tilting the head backwards to help move the tongue off of the posterior pharynx can alleviate this.

Pay further attention to obstruction of the airway. Common findings in trauma are obstructions that may include vomit, teeth or other foreign bodies, which should be removed immediately when possible.

In trauma patients, it is important to try to maintain the alignment of the cervical spine during all aspects of the primary survey, so the head tilt method is not used. In such cases the jaw-thrust is used to move the tongue. Immobilize the patient’s head and neck by using boards, tape, bulky dressings, or towels or by assigning someone to hold the head immobile. Once a patient is immobilized, removal of these measures requires careful decision-making.

If airway patency remains a problem, endotracheal intubation or the placement of a breathing tube by qualified providers will usually need to be accomplished depending on the clinical setting.

B–Breathing

Assessment of the adequacy of breathing and respirations is the second step to the primary survey. During this phase evaluating for signs and symptoms of respiratory distress and identifying life-threatening injuries associated with the pulmonary system in trauma patients is undertaken.

Ensure the chest is rising and falling, note the approximate frequency and determine whether the patient is breathing too fast, too slow, or just about normal. Observe for signs and symptoms of respiratory distress such as accessory muscle use of the chest wall, and or accessory muscle use in the neck area. Patients in respiratory distress will often have increased respiratory rate with and exaggeration of the use of the neck and chest wall muscles. Brief auscultation of the lung sounds to ensure air is flowing in both lungs is usually accomplished during this phase.

In trauma patients, consideration must be given to the potential diagnosis of tension pneumothorax, as well as the integrity of the chest wall and rib cage. Observing for paradoxical motion, meaning unusual movement of the chest wall during respirations, can indicate a flail chest, in which case, there are many rib fractures that allow for a portion of the chest wall to be free-floating.

Open chest wounds, otherwise known as sucking chest wounds, allow air to enter the pleural space, leading to collapse of the underlying lung (pneumothorax). They can be identified by a sucking sound or bubbling of blood in a chest wound associated with the patient’s breathing. If identified, they should be covered with an occlusive dressing.

Pneumothorax is the collapse of a lung away from the chest wall. Pneumothorax can be classified as open, as is the case of a sucking chest wound, or closed, which may occur because of a lung laceration from a rib fracture. They are identified by findings of an absence or decreased volume of lung sounds on the side of the pneumothorax. The conscious patient with a pneumothorax may complain of sharp pain associated with inspiration.

Tension pneumothorax occurs when an air leak in the lung causes a collapse of the lung and a pressure to build up on the injured side. Tension pneumothorax can be diagnosed by the absence of breath sounds on the side of the pneumothorax, profound distention of the jugular veins, and the later findings of tracheal deviation away from the side of the pneumothorax. If tension pneumothorax is suspected in a critically ill trauma patient, a needle decompression of the chest wall should occur immediately. Tension pneumothorax can rapidly cause severe shock and death if left untreated.

C–Circulation

In this step of the primary survey, the health care provider is trying to determine a rough estimate of the cardiopulmonary system with regard to circulation and blood pressure. Attempting to stabilize end organ perfusion, such as the brain, heart and lungs, is key to survival for the critically ill and injured.

Initially attempting to palpate the radial pulse is a key physical exam component to completing this step. The radial pulse check can yield considerable amounts of information during the assessment of a critically ill patient. Noting the pulse rate (i.e., too fast, too slow, or approximately normal) and the quality of the pulse provides significant information. A rapid, thready, pulse can indicate shock. It is useful to know that if the radial pulse is palpable, the systolic blood pressure can be estimated to be at least 80 mm Hg. If the radial pulse is not palpable, immediately assess the femoral pulse, which approximates the systolic pressure at 70 mm Hg if it is present.

While assessing the pulse checks, simultaneously note the skin color, moisture, and color. Pale, sweaty, cool skin findings are also signs of shock and hypoperfusion that result from the activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

If the patient’s skin is warm, dry, and of normal color, it is likely that oxygenation and flow of blood to the periphery are adequate. In shock, peripheral blood flow is shunted centrally; thus, skin changes are early indicators of hypovolemic or cardiogenic (low cardiac output) shock. Key diagnostic skin signs associated with these major acute cardiopulmonary derangements are gray, mottled, or cyanotic color; cold skin temperature; and markedly sweaty skin. The last sign, termed diaphoresis, is caused by activation of the sympathetic nervous system by any major threat to homeostasis.

In trauma patients, it is important to also assess for signs of life-threatening external bleeding, arterial or venous, which should be brought under control if identified. Direct pressure over bleeding is the best first step to control bleeding. If severe bleeding of an injured extremity persists, a tourniquet should be applied to bring major bleeding under control.

D–Disability

Overall mental status can be a key indicator to end-organ perfusion of the brain and serve as an important baseline test of trauma patients who are having an evolving mental status change secondary to brain injury. Central nervous system function is noted in this phase by use of a simplified mental status evaluation process using the mnemonic known as AVPU. The AVPU mnemonic for level of consciousness is as follows:

E–Expose

More specific to trauma patients, depending on the clinical setting, it is necessary to expose the patient as much as possible to try and further identify any further threats to life. The clothes and other debris raise the possibility of concealing major bleeding; open chest wounds; and other physical examination signs such as large areas of contusions, which can be clues to major internal injuries. After the assessment is made, it is important to cover the patient to ensure minimizing the loss of body heat.

Vital Signs

Assess and Reassess Vital Signs

Once the steps of the initial survey are completed as described above, formal vital signs should be obtained. These include a detailed measuring of the patient’s heart rate, respirations, blood pressure, and mental status. Depending on the clinical setting, vitals signs should also include body temperature and pulse oximetry readings.

If a vital sign is abnormal, begin to treat the abnormality to bring it back to normal. For example, if the patient is breathing spontaneously at a rate of only five breaths per minute, augment and assist the patient’s breathing so that the depth and rate of breathing are normalized. Assisting ventilations can be accomplished by applying interspersed mouth-to-mouth ventilations if a barrier protective device is available. Employing a bag-valve-mask device, or performing endotracheal intubation and placing the patient on a ventilator may also be indicated. The exact therapy will vary widely depending on the clinical setting.

In a similar manner, the blood pressure can be supported by simply raising the legs, which empties the blood stored in the lower extremity venous system back into the central circulation. If possible, establishing intravenous access should occur rapidly depending on the clinical setting.

In trauma patients, particular attention should be given to keeping external bleeding controlled, re-evaluating for developing tension pneumothorax, and considering the need for immediate blood transfusions.

Once you believe that the patient is no longer in imminent risk of death or further instability, it is appropriate to move on to the secondary survey.

Secondary Survey

History

Documenting the history from an acutely ill or injured patient conforms closely to documentation of the standard history, but it is abbreviated and focused to allow rapid diagnostic and management decisions to be made.

In the Secondary Survey, document a history from the patient, the patient’s relatives, emergency department personnel, or bystanders. The Secondary Survey is a systematic method for determining whether other conditions or injuries are present and necessitate attention. This survey consists of a rapid interview, a check of the vital signs, and a focused physical examination. The mnemonic SAMPLE can be helpful in gathering pertinent information:

The utilization of the SAMPLE survey is important to try and uncover the details that will allow for identification or diagnosis of the underlying cause of the patient’s acute illness or injury that will allow for appropriate further testing and or initiation of treatment. For example, the finding in the history that a patient has had several days of fever, cough, and loss of appetite may indicate that the underlying illness may be pneumonia.

In dealing with a trauma patient, trying to identify the mechanism of injury is helpful. Did the patient sustain blunt trauma, such as an automobile accident, or was a weapon used that may have led to cause a penetrating injury? In the case of a vehicular accident, ascertain whether the patient was ejected from the car; the use of seat belts; and whether or not there was a loss of consciousness, which may indicate a head injury such as a concussion.

In trauma patients who are alert, asking them to identify the area associated with pain may help direct the physical examination further. In general, the secondary assessment of the patient involves examination of three main regions: the head and neck, the torso, and the extremities.

Secondary Survey Physical Examination

Head and Neck

Look at the victim’s face. In the acutely ill, a patient’s sunken eyes and profoundly dry mucous membranes along with cracked lips can indicate severe dehydration. Are the mucous membranes pale? This could help identify critical anemia. Evaluate skin color and temperature.

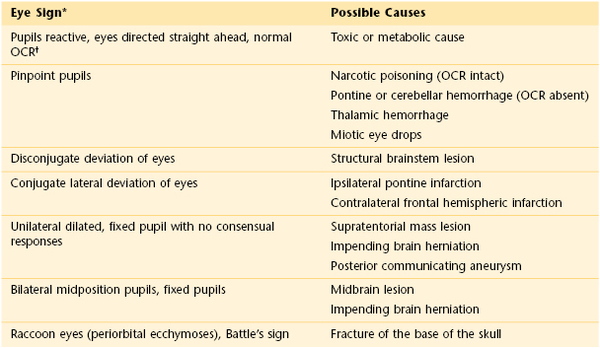

In the trauma patient, is there evidence of raccoon eyes or Battle‘s sign? A patient with raccoon eyes is shown in Figure 7-32. Periorbital ecchymoses, or raccoon eyes, are seen 6 to 12 hours after a fracture of the base of the skull. Battle’s sign is ecchymosis behind the ear caused by basilar skull or temporal bone fractures; this sign may take 24 to 36 hours to develop. While the examination of the eyes for pupillary size and responsiveness to light is actually part of the neurological examination, it is usually performed when examining the face. Are the pupils equal? Are the pupils pinpoint? Is there a unilateral dilated pupil? Are the pupils fixed? Table 23-1 reviews the eye signs in a comatose patient.

Table 23–1

Eye Signs in a Comatose Patient

* Eye signs are difficult to evaluate in patients with artificial lenses, prosthetic eyes, contact lenses, or cataracts or after cataract surgery.

† “Doll’s eyes”: Rotate the head quickly but gently from side to side. In an unconscious patient with an intact brain stem, the eyes move conjugately in a direction opposite the head turning.

OCR, Oculocephalic reflex.

Is there bleeding or discharge from the ears, nose, or mouth?

Palpate the head. Note for signs of crepitus, bleeding, or scalp hematoma.

Inspect the posterior neck for tenderness in the midline of the spine or any step-offs of the spinous processes of the posterior cervical spine. Inspect the anterior neck: note if the trachea is deviated and the level of distention of the neck veins. If they are both positive findings, suspect a chest injury, such as a tension pneumothorax. Palpate the neck for crepitus, which is indicative of air under the skin from rupture of the lung.

If there is no tenderness of the neck, the patient has no other painful injuries, and he or she is not intoxicated, ask him or her to move the neck through a full range of motion slowly. Have the patient stop if pain is encountered.

Chest

Conducting a detailed examination of the chest is important in the critically ill or injured patient. Auscultation of the breath sounds in detail and noting the quality of the findings can provide vital clues. Rales, rhonchi, and wheezing can be signs of underlying pulmonary or cardiac conditions leading to the patient’s illness. Heart sounds should be auscultated, with any major findings of murmurs, rubs, or gallops noted.

In trauma patients, the presence or absence of breath sounds should be frequently evaluated, as should observation of the symmetrical rise and fall of the chest. As mentioned earlier, paradoxical or abnormal chest movement with respirations may be a sign of a flail chest, which should be stabilized. Muffled heart sounds, particularly if combined with distended jugular veins, may be a sign of cardiac tamponade, another rapidly life-threatening condition if caused by trauma.

Abdomen

Inspect the abdomen. Is abdominal distention present? Are bowel sounds present? Gently palpate the abdomen, quadrant by quadrant, noting the presence of tenderness. If the patient is a woman of childbearing age, always consider the possibility that she may be pregnant.

In trauma patients, be alert for evidence of blunt abdominal trauma, such as focal areas of tenderness, ecchymosis, abrasions, contusions, or the presence of an open abdominal wound. Cullen‘s sign is a bluish discoloration around the umbilicus indicative of intra-abdominal bleeding or trauma. Grey Turner‘s sign is ecchymotic discoloration around the flanks, which is suggestive of retroperitoneal bleeding. Swelling or ecchymosis often occurs late; therefore, its presence is extremely important. Right upper quadrant pain may indicate liver injury, which is the most commonly injured abdominal organ in adult blunt trauma, while left upper quadrant pain is suspicious for splenic injury.

Inspect the anus and the perineum. Perform a rectal examination to assess anal sphincter tone, to determine whether blood is present, and to verify that the prostate is in its normal position.

Pelvis

Use the heels of your hands to apply gentle downward pressure on the anterior superior iliac spine and on the symphysis pubis. Is tenderness present? Is there any abnormal motion? If so, there may be a fracture of the pelvic ring. Inspect the urethral meatus for the presence of blood. If found, this can be further indication of pelvic or bladder trauma.

Extremities

For acutely ill patients, the inspection of the distal extremities should include observations associated with indicators of adequate circulation. The temperature, color, moisture, and finding of capillary refill should be evaluated. Capillary refill is an assessment of perfusion. It is the time required for a patient’s skin color to return to normal after the nail bed has been pressed. The normal refill time is less than 2 seconds. Prolongation of the capillary refill indicates perfusion abnormalities.

In certain infectious disease situations, checking the nail beds for the presence of splinter hemorrhages can be useful; if found, they may indicate endocarditis.

In patients with major trauma, there should be an examination of all their bones and joints—to assess for stability of structure and for function. Noting major deformities of long bones and joints is important. Splinting deformed long bones can assist in controlling blood loss associated with fractures.

A distal neurovascular examination of each extremity that notes the motor, sensory, and vascular function should be assessed, with particular attention paid to those areas distal to a suspected injury.

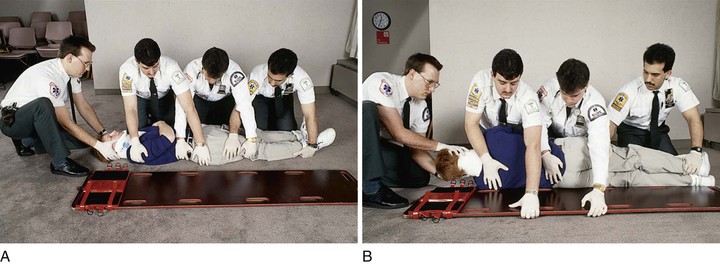

Back

Inspect the back, looking for obvious signs of injury. This is best performed with a coordinated log roll of the patient; with someone at the head, maintain the alignment of the cervical spine. To do this, you need at least four assistants: one to control the head and neck, two to roll the patient onto the side, and one to cautiously examine the back. Figure 23-4 shows this log-roll procedure. Note the presence of any signs of injury, such as bleeding, contusions, abrasions, or focal areas of pain. Finally, palpate the entire midline spinal column, assessing for point tenderness or step-offs of the spine, which can indicate severe bony injury to the axial spine.

Figure 23–4 Log-roll procedure. A, Positioning for log rolling. (1) Apply a cervical spine immobilization device and place the patient’s arms at the side. Note that one emergency management technician (EMT) maintains cervical immobilization manually throughout this procedure. (2) Three EMTs can be positioned at the side of the patient at the level of the chest, hips, and lower extremities while the long spine board is positioned on one side of the patient. (3) Check the patient’s arm on the side of the EMTs for injury before log-rolling the patient, and then align the lower extremities. Note: The EMT at the lower extremities holds the patient’s lower leg and thigh region, the EMT at the hips holds the patient’s lower legs and places the other hand on top of the patient’s buttocks, and the EMT at the chest holds the patient’s arms against the body and at the level of the lower buttocks. B, Log rolling the patient. (4) On command from the EMT at the head, all EMTs rotate the patient toward themselves, keeping the body in alignment. (5) The EMTs then reach across with one hand and pull the board beneath the patient’s arm. (6) On command from the EMT at the head, they gently roll the patient onto the board and then roll the board to the ground. (7) Strap the patient’s torso and extremities securely to the board, and immobilize the head.

The Pediatric Emergency

When assessing an acutely ill child, approach the pediatric emergency as you would an emergency in an adult from an organizational standpoint, but recognize the smaller size of the patient and the difference in the physiologic responses to acute illness and injury. In particular, the pediatric patient has less reserve capacity to compensate for dysfunction of the cardiopulmonary systems. The primary assessment of an acutely ill or injured child is the same as that of an adult.

The most dangerous common, life-threatening pediatric emergencies result in respiratory distress. For this reason, it is recommended that all acutely ill pediatric patients be placed on supplemental oxygen.

Respiratory distress in a pediatric patient may arise from a variety of conditions that result from upper or lower airway disease. Common pediatric respiratory problems of the upper airway include croup (laryngotracheobronchitis), epiglottitis, foreign bodies, and bacterial tracheitis. Lower airway obstruction may result from asthma, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and foreign bodies.

The hallmarks of respiratory distress are tachypnea, nasal flaring, retractions, cyanosis, head bobbing, prolonged expiration, and grunting. Children with upper airway disease often exhibit stridor, a sound heard on inspiration associated with partial airway obstruction. A child with severe distress may be in the tripod position, leaning forward onto an outstretched arm in an attempt to improve respiration. If this position is noted and accompanied by drooling, it is a finding associated with epiglottitis, a condition that can have a rapid progression to respiratory failure. In cases of suspected epiglottitis, it is crucial to keep the patient as calm as possible while initiating treatment to avoid further swelling of the epiglottis.

Fortunately, the incidence of epiglottitis has decreased, presumably because of the Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB) vaccine. If epiglottitis is suspected, do not examine the airway without being prepared to provide airway stabilization on an emergency basis. Manipulation of the child’s airway can lead to complete airway obstruction. Table 23-2 compares some of the important differences between epiglottitis and croup.

Table 23–2

Differentiation Between Epiglottitis and Croup

| Characteristics | Epiglottitis | Croup |

| Cause | Haemophilus influenzae type B | Viral, usually parainfluenza virus |

| Age of child | Any age (peak, 3–7 years) | 3 months–3 years |

| Clinical appearance | Extremely ill (“toxic”) | Not extremely ill |

| Season | No seasonal predominance | Autumn and winter |

| Clinical onset | Rapid | Insidious |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Rare | Common |

| Fever | >104° F (40° C) | <103° F (39.5° C) |

| Sore throat | Severe | Variable |

| Cough | Not “barking”; throughout the day | “Barking”; during the night |

| Drooling | Prominent | None |

| Stridor | On inspiration | On inspiration and expiration |

| Position | Sitting forward with neck extended and mouth open | Variable |

| Epiglottis | Bright red | Normal |

Foreign body aspiration is common between the ages of 1 to 2 years. In a child, consider foreign body aspiration in the following situations:

If the patient loses the ability to move air, indicated by lack of cough, inability to speak, or inability to remain conscious, emergency attempts at clearing the airway should be undertaken. Immediately place the child face down, with the head lower than the torso, over your arm, which is placed on your thigh. Support the child’s head by holding his or her jaw. Deliver five forceful back blows with the heel of your other hand between the child’s scapulae. Turn the child onto the back while holding the child’s head. Place two fingertips on the middle portion of the sternum, one fingerbreadth below the nipples. Depress the sternum 1 inch. Repeat this maneuver up to five times. Attempt to remove any visible material from the pharynx. Repeat the back blows and chest thrusts until the object is dislodged.

If the child becomes unconscious, check the mouth for a foreign body, and then perform mouth-to-mouth breathing. Gently tilt the child’s head back while placing the other fingers under the jaw at the chin, and lift the chin upward. Seal the child’s mouth and nose with your mouth. Deliver two breaths, watching the chest rise. If the breaths do not go in, repeat the back blows and chest thrusts. Have someone call for help.

Dehydration is another important and common pediatric emergency. The most common causes are vomiting and diarrhea. In a child with mild dehydration (<5%), there may be only a slight decrease in mucous membrane moisture. In severe dehydration (15%), the following are commonly found:

• Parched mucous membranes; no tears

• Markedly decreased skin turgor

• Capillary refill longer than 2 seconds

• Orthostatic hypotension: systolic pressure less than 80 mm Hg

Immediate intravenous infusion of isotonic fluids should be started in children with severe dehydration with initial doses aimed at 20 mL/kg of body weight followed by frequent reassessments.

The secondary assessment outlined earlier and the AVPU mental status documentation mnemonic are just as important for children as for adults and should be frequently re-evaluated in critically ill children.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Capehorn DMW, Swain AH, Goldsworthy LL. A handbook of paediatric accident and emergency medicine: a symptom-based guide. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 1988.

Field JM, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circ. 2010;122(suppl 3):S640.

Henry MC, Stapleton ER. EMT prehospital care. ed 4. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2011.

Howell JM, et al. Emergency medicine. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 1997.

Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM. Rosen’s emergency medicine, concepts and clinical practice. ed 7. Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2010.

Revere C, Hasty R. Diagnostic and characteristic signs of illness and injury. J Emerg Nurs. 1993;19:2.

1 The author thanks Paul Phrampus, MD, FACEP, Associate Professor, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA and Institute Director of the Peter M. Winter Institute for Simulation, Education and Research (WISER) Center at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine for reviewing this chapter.