The Acute Scrotum

The term acute scrotum is defined as acute scrotal pain with or without swelling and erythema. Early recognition and prompt management are imperative because of the possibility of testicular torsion as the etiology with permanent ischemic damage to the testis. Box 52-1 lists the differential diagnoses for the acute scrotum. Although most conditions are nonemergent, prompt differentiation between testicular torsion and other causes is critical. Age at presentation is important because torsion of the appendix testis/epididymis is most common in prepubertal boys, whereas testicular torsion more commonly presents in neonates and adolescents.1–3

Testicular Torsion

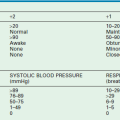

Torsion of the testis results from twisting of the spermatic cord which compromises the testicular vasculature and results in infarction. Even if the testis is not removed, the consequent ischemic damage can affect testicular morphology and fertility. There appears to be a 4-8-hour window before significant damage occurs once torsion develops.4 Table 52-1 shows that the probability of testicular salvage declines significantly beyond six hours. Emergency exploration is indicated even beyond this window because testicular viability is difficult to predict.5

TABLE 52-1

Duration of Torsion and Testicular Salvage Rates

| Duration of Torsion (Hours) | Testicular Salvage (%) |

| <6 | 85–97 |

| 6–12 | 55–85 |

| 12–24 | 20–80 |

| >24 | <10 |

Data from Smith-Harrison L, Koontz WW Jr. Torsion of the testis: Changing concepts. In: Ball TP Jr, Novicki DE, Barrett DM, et al, editors. AUA Update Series, vol. 9 (lesson 32). Houston: American Urological Association Office of Education; 1990.

Two types of torsion occur: intravaginal and extravaginal. Intravaginal torsion is more common in children and adolescents (compared to neonates), and occurs when the spermatic cord twists within the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 52-1). Intravaginal torsion develops because of abnormal fixation of the testis and epididymis within the tunica vaginalis. Normally, the tunica will invest the epididymis and posterior surface of the testis, fixing it to the scrotum with a vertical lie. Abnormal fixation occurs when the tunica vaginalis attaches more proximally on the spermatic cord, creating a long mesorchium around which the testis can twist. The testis will then lie horizontally and the pendulous testis is predisposed to twisting with leg movement or cremasteric contraction. This anatomic variant is classically described as the ‘bell-clapper’ deformity and has an incidence as high as 12% in cadaveric studies. Often, it is found in the contralateral scrotum as well.6

FIGURE 52-1 Bell-clapper deformity. The tunica vaginalis inserts very high on the spermatic cord, which predisposes to testicular torsion.

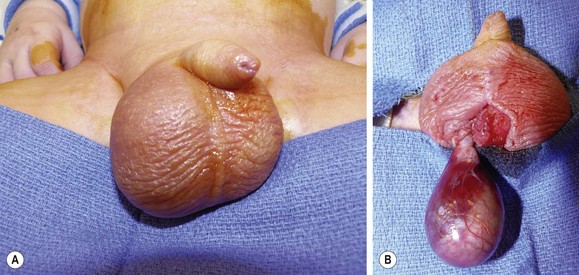

Extravaginal torsion occurs perinatally when the spermatic cord twists proximal to the tunica vaginalis (Fig. 52-2). During testicular descent into the scrotum, the tunica vaginalis is not firmly fixed to the scrotum, allowing the tunica and testis to spin on the vascular pedicle.

FIGURE 52-2 (A) Shortly after birth, this newborn was found to have an enlarged and erythematous right hemiscrotum. It was unclear whether or not the right hemiscrotum was enlarged at birth. The baby underwent scrotal exploration through a median raphe incision and was found to have an extravaginal testicular torsion. (B) With this anomaly, the testis lies within the tunica vaginalis and the entire complex has twisted. An alternative approach would be to explore this child through an inguinal approach due to concerns about a possible testicular tumor.

Testicular torsion typically occurs before age 3 years or after puberty. It is less common in prepubertal boys and after age 25 years. Patients present with the sudden onset of severe, unilateral pain in the testis, lower thigh, or lower abdomen, often associated with nausea and vomiting. Episodes of intermittent testicular pain may precede the acute presentation, suggesting prior incomplete torsion with spontaneous detorsion. Physical examination may reveal an enlarged testis that is retracted up toward the inguinal region with a transverse orientation and an anteriorly located epididymis. However, it is usually difficult to obtain a good exam because of the scrotal pain and tenderness. In contrast, focal tenderness at the superior pole of the testis or along the epididymis is often found with a torsed appendix testis or epididymitis (Fig. 52-3). Depending on the duration of torsion, the hemiscrotum can show varying degrees of swelling and erythema, which may obliterate landmarks and make the examination more difficult. The cremasteric reflex is often absent with testicular torsion, but a positive reflex does not reliably exclude it.7–9

FIGURE 52-3 A torsed and gangrenous appendix testis is shown. This is the cause of the ‘blue dot’ sign.

The diagnosis of testicular torsion is usually clinically apparent and managed by immediate scrotal exploration. When torsion is difficult to diagnosis, other studies may be beneficial. A urinalysis revealing pyuria and bacteriuria is more indicative of infectious epididymitis/orchitis, but can also be found with torsion. High-resolution ultrasonography (US) with color flow Doppler and radionuclide imaging allows determination of testicular blood flow. Ultrasound is more commonly used because it allows determination of the blood flow, is less time consuming, is more readily available, and does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation.10,11 In experienced hands, color flow Doppler ultrasound imaging has a sensitivity of 89.9%, a specificity of 98.8%, and a false-positive rate of 1%.12 Also, Doppler ultrasound may detect coiling of the spermatic cord, indicating torsion, even with normal blood flow within the testis.13 Ultrasound should only be used when the diagnosis is equivocal because imaging studies will only delay scrotal exploration.

If testicular torsion is suspected but a delay to the operating room is unavoidable, manual detorsion can be attempted. Detorsion is performed with a medial to lateral, ‘open book’ rotation because this will be the correct direction in two-thirds of patients.14 If successful, the testis will drop lower in the scrotum and the patient will report sudden pain relief. If the initial attempt is not successful, an attempt in the reverse direction may be warranted.15 Although these maneuvers may decrease the degree of ischemia, prompt exploration and fixation remain mandatory because the detorsion may not be complete and torsion can reoccur.

Exploration is typically performed using a median raphe scrotal incision. The symptomatic hemiscrotum is entered and the testis delivered, detorsed, and placed in warm, moist sponges while the contralateral hemiscrotum is explored. The unaffected testis should be fixed to the scrotal wall with nonabsorbable suture in at least three points. Excluding the tunica vaginalis allows better fixation of the testis to the scrotum.16,17 Attention is then turned back to the affected testis. If the testis is clearly nonviable, it should be removed to avoid potential damage to the contralateral testis from the formation of antisperm antibodies. If the torsed testis becomes reperfused or is bleeding from the cut surface, it should be fixed in the same fashion as the contralateral testis. Bilateral fixation reduces the probability of torsion in the future, but cases of torsion after fixation have been described.18 Therefore, any patient with symptoms of testicular torsion should be evaluated and managed appropriately, regardless if previous fixation was performed.

Intermittent Testicular Pain

Intermittent testicular pain is not uncommon in adolescent males, and may represent intermittent torsion with spontaneous resolution.19 This diagnosis should be strongly considered in patients with significant testicular pain that has resolved, especially if there have been multiple episodes. This suspicion is reinforced if the testis has a transverse orientation or excess mobility. The diagnosis could be confirmed with Doppler ultrasound while symptomatic. If clinical concern remains despite a normal physical examination, elective scrotal exploration looking for a ‘bell-clapper’ deformity may be warranted.

Perinatal Testicular Torsion

The term perinatal torsion involves both prenatal and postnatal events with most (75%) occurring prenatally.20 Distinguishing between the two types can be difficult, but knowing the difference affects the timing of operation. Prenatal torsion presents as a hard, nontender scrotal mass noted at birth, usually with underlying dark skin discoloration and fixation of the skin to the mass. These findings suggest testicular infarction secondary to a prior torsion. Postnatal torsion presents as an acutely inflamed scrotum with erythema and tenderness (see Fig. 52-2). The scrotum is often reported as normal at delivery, suggesting an acute postnatal event. This diagnosis requires emergent exploration with detorsion and bilateral fixation.

The timing of exploration for prenatal torsion has been controversial. Some surgeons believe exploration is not indicated because of negligible salvage rates and increased neonatal anesthetic risks.21 However, this approach is challenged by reports of asynchronous torsion with loss of the remaining contralateral testis.22–24 Furthermore, if the torsion were to happen at or just prior to delivery, testicular salvage may be possible. One series of 30 neonates with torsion who were explored within 6 hours of birth found two testes that could be salvaged and demonstrated normal growth 1 year later.25 Therefore, many surgeons have become more aggressive with earlier exploration of these infarcted testes to fix the contralateral side and prevent the potential for bilateral torsion.

Although a testicular teratoma or a hernia sac filled with meconium or blood can mimic prenatal torsion, our practice has been early exploration. Postnatal torsion clearly mandates emergent exploration because salvage rates have been reported as high as 40–50%, which is similar to torsion later in life.26 Scrotal exploration is performed through an inguinal incision because a testicular tumor may actually be present and a scrotal incision could lead to spread to the inguinal nodes.27,28 Contralateral exploration is accomplished through a transverse scrotal incision, with placement of the testis in a dartos pouch between the external spermatic fascia of the scrotum and the dartos fascia. This technique is less traumatic to the small, delicate neonatal gonad and provides similar fixation to using sutures.16,17

Conditions Mimicking Testicular Torsion

Torsion of Testicular Appendages

Torsion of the appendix testis or appendix epididymis is the most common cause of an acute scrotum and is frequently misdiagnosed as acute epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis. The testicular appendage represents a vestigial remnant of the Müllerian duct, and the epididymal appendage is of Wolffian duct origin. Torsion of these appendages occurs most commonly between ages 7 and 10 years. It is hypothesized that a prepubertal hormonal boost stimulates these structures, producing an increase in size and making them susceptible to twisting.29

Patients with appendage torsion present with sudden onset of pain and nausea. Results of the urinalysis are usually normal. The appendage can usually be palpated and is exquisitely and focally tender. The examiner may be able to elicit differential tenderness between the upper and lower poles of the affected testis. Classically called the ‘blue dot’ sign, the inflamed and ischemic appendage may be seen through the scrotal skin as a subtle blue-colored mass (see Fig. 52-3).30 As inflammation increases, the epididymis, testis, and scrotal tissues become edematous and erythematous, and the diagnosis becomes more difficult. Ultrasound early in the presentation demonstrates a discrete appendage. However, later, it may only show increased blood flow to the adjacent epididymis and testis or, possibly, a reactive hydrocele, resulting in the misdiagnosis of acute epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis.31

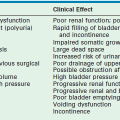

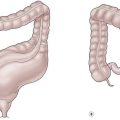

Appendage torsion can occur at five anatomic sites: appendix testis, appendix epididymis, paradidymis/organ of Giraldes, and superior and inferior vas aberrans of Haller (Fig. 52-4).32–34 Exploration is indicated when the diagnosis is unclear or when the symptoms are prolonged and fail to resolve spontaneously. The torsed appendage can be easily excised through a small scrotal incision with immediate symptom relief.

Epididymitis

Viral infections are believed to be a common cause for acute epididymitis, but are usually diagnosed presumptively. Mumps orchitis is rare and occurs in approximately one-third of infected postpubertal boys.35 Adenovirus, enterovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza virus infections have also been found. Management is supportive, antibiotics are not indicated, and the pain is generally self-limited.

Idiopathic Scrotal Edema

Scrotal swelling of unknown etiology is termed idiopathic scrotal edema and usually affects boys between the ages of 5 to 9 years. The syndrome is characterized by the insidious onset of swelling and erythema that typically begins in the perineum or inguinal region, and spreads to the hemiscrotum. Pruritus can occur, but the testis is not tender and ultrasound shows normal testicular blood flow. Contact dermatitis, insect bites, and minor trauma are often misdiagnosed as the etiology. Evaluation should seek to exclude cellulitis from an adjacent infection (inguinal, perirectal, or urethral). Treatment is with antihistamines or topical corticosteroids. If cellulitis is a concern, oral antibiotics can be administered.36

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura

Henoch–Schönlein purpura is a vasculitic syndrome that can involve the skin, joints, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems. Up to one-third of patients develop pain, erythema, and swelling of the scrotum and spermatic cord, most commonly in boys younger than 7 years of age. Doppler ultrasound demonstrates normal blood flow to the testis. Patients can also experience skin purpura, joint pain, and hematuria. Supportive measures are typically adequate, although systemic corticosteroids may be helpful.37,38 Despite the rarity of coincident diagnoses, patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura and testicular torsion have been described.39

Other Conditions

Other causes of the acute scrotum include an incarcerated inguinal hernia, hydrocele, voiding dysfunction, and neoplasia. Testicular tumors can occur in the neonatal period and early childhood, although they are usually not associated with pain or scrotal wall changes. They are usually firm on examination and should be further evaluated with ultrasound. Management is tailored to the diagnosis. See Chapter 51 for more information about testicular tumors.

References

1. Sheldon, CA. Undescended testis and testicular torsion. Surg Clin North Am. 1985; 65:1303–1329.

2. Clift, VL, Hutson, JM. The acute scrotum in childhood. Pediatr Surg Int. 1989; 4:185–188.

3. Murphy, JP, Gatti, JM. Current management of the acute scrotum. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007; 16:58–63.

4. Bartsch, G, Frank, S, Marberger, H, et al. Testicular torsion: Late results with special regard to fertility and endocrine function. J Urol. 1980; 124:375–378.

5. Bentley, DF, Ricchiuti, DJ, Nasrallah, PF, et al. Spermatic cord torsion with preserved testis perfusion: Initial anatomical considerations. J Urol. 2004; 172:2373–2376.

6. Caesar, RE, Kaplan, GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology. 2004; 44:114–116.

7. Cifti, AO, Senocak, ME, Tanyel, FC, et al. Clinical predictors for differential diagnosis of acute scrotum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 14:333–338.

8. Nelson, CP, Williams, JF, Bloom, DA. The cremasteric reflex: A useful but imperfect sign in testicular torsion. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:1248–1249.

9. Rabinowitz, R. The importance of the cremasteric reflex in acute scrotal swelling in children. J Urol. 1984; 132:89–90.

10. Nussbaum Blask, AR, Bulas, D, Shalaby-Rana, E, et al. Color Doppler sonography and scintigraphy of the testis: A prospective, comparative analysis in children with acute scrotal pain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002; 18:67–71.

11. Wu, HC, Sun, SS, Kao, A, et al. Comparison of radionuclide imaging and ultrasonography in the differentiation of acute testicular torsion and inflammatory testicular disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2002; 27:490–493.

12. Baker, LA, Sigman, D, Matthews, RI, et al. An analysis of clinical outcomes using color Doppler testicular ultrasound for testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 2000; 105:604–607.

13. Karmazyn, B, Steinberg, R, Kornreich, L, et al. Clinical and sonographic criteria of acute scrotum in children: A retrospective study of 172 boys. Pediatr Radiol. 2005; 35:302–310.

14. Kiesling, VJ, Jr., Schroeder, DE, Pauljev, P, et al. Spermatic cord block and manual reduction: Primary treatment for spermatic cord torsion. J Urol. 1984; 132:921–923.

15. Sessions, AE, Rabinowitz, R, Hulbert, WC, et al. Testicular torsion: Direction, degree, duration, and disinformation. J Urol. 2003; 169:663–665.

16. Bellinger, MF, Abromowitz, H, Brantley, S, et al. Orchiopexy: An experimental study of the effect of surgical technique on testicular histology. J Urol. 1989; 142:553–555.

17. Rodriguez, LE, Kaplan, GW. An experimental study of methods to produce intrascrotal testicular fixation. J Urol. 1988; 139:565–567.

18. Mor, Y, Pinthus, JH, Nadu, A, et al. Testicular fixation following torsion of the spermatic cord—does it guarantee prevention of recurrent torsion events? J Urol. 2006; 175:171–173.

19. Stillwell, TJ, Kramer, SA. Intermittent testicular torsion. Pediatrics. 1986; 77:908–911.

20. Das, S, Singer, A. Controversies of perinatal torsion of the spermatic cord: A review, survey and recommendations. J Urol. 1990; 143:231–233.

21. Stone, KT, Kass, EJ, Cacciarelli, AA, et al. Management of suspected antenatal torsion: What is the best strategy? J Urol. 1995; 153:782–784.

22. Olguner, M, Akgur, FM, Aktug, T, et al. Bilateral asynchronous perinatal testicular torsion: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35:1348–1349.

23. Sorenson, MD, Galansky, SH, Striegl, AM, et al. Prenatal bilateral extravaginal testicular torsion: A case presentation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004; 20:892–893.

24. Ahmed, SJ, Kaplan, GW, DeCambre, ME. Perinatal testicular torsion: Preoperative radiological findings and the argument for urgent surgical exploration. J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43:1563–1565.

25. Pinto, KJ, Noe, HN, Jerkins, GR. Management of neonatal testicular torsion. J Urol. 1997; 158:1196–1197.

26. Sorenson, MD, Galansky, SH, Striegl, AM, et al. Perinatal extravaginal torsion of the testis in the first month of life is a salvageable event. Urology. 2003; 62:132–134.

27. Lusiri, A, Vogler, C, Steinhardt, G, et al. Neonatal cystic testicular gonadoblastoma: Sonographic and pathologic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 1991; 10:59–61.

28. Masterson, JS, McCullough, AR, Smith, RR, et al. Neonatal gonadal stromal tumor of the testis: Limitations of tumor markers. J Urol. 1985; 134:558–559.

29. Samnakay, N, Cohen, RJ, Orford, J, et al. Androgen and oestrogen receptor status of the human appendix testis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003; 19:520–524.

30. Dresner, ML. Torsed appendage. Diagnosis and management: Blue dot sign. Urology. 1973; 1:63–66.

31. Karmazyn, B, Steinberg, R, Livne, P, et al. Duplex sonographic findings in children with torsion of the testicular appendages: Overlap with epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:500–504.

32. Rolnick, D, Kawanoue, S, Szanto, P, et al. Anatomical incidence of testicular appendages. J Urol. 1968; 100:755–756.

33. Orazi, C, Fariello, G, Malena, S, et al. Torsion of paradidymis or Giraldes’ organ: An uncommon cause of acute scrotum in pediatric age group. J Clin Ultrasound. 1989; 17:598–601.

34. Ballesteros Sampol, JJ, Munne, A, Bosch, A. A vas aberrans torsion. Br J Urol. 1986; 58:97.

35. Beard, CM, Benson, RC, Jr., Kelalis, PP, et al. The incidence and outcome of mumps orchitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935 to 1974. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977; 52:3–7.

36. Rabinowitz, R, Hulbert, WC, Jr. Acute scrotal swelling. Urol Clin North Am. 1995; 22:101–105.

37. Clark, WR, Kramer, SA. Henoch–Schönlein purpura and the acute scrotum. J Pediatr Surg. 1986; 21:991–992.

38. Soreide, K. Surgical management of nonrenal genitourinary manifestations in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:1243–1247.

39. Loh, HS, Jalan, OM. Testicular torsion in Henoch-Schönlein syndrome. BMJ. 1974; 2:96–97.