5 The Acute Abdomen

Etiology and Pathogenesis

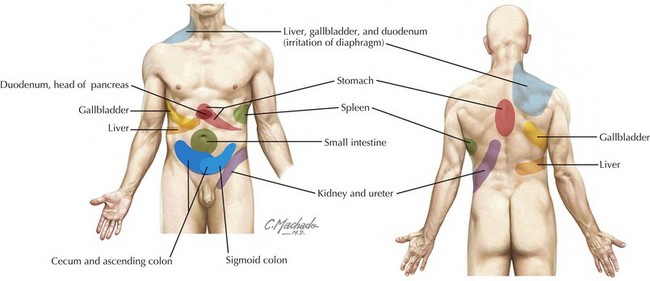

Referred pain is often perceived at sites distant from the affected organ and may be described either as sharp and localized or as a vague aching sensation (Figure 5-1). Examples include irritation of the parietal pleura of the lung perceived as abdominal wall pain and inflammation of the gallbladder perceived as scapular pain.

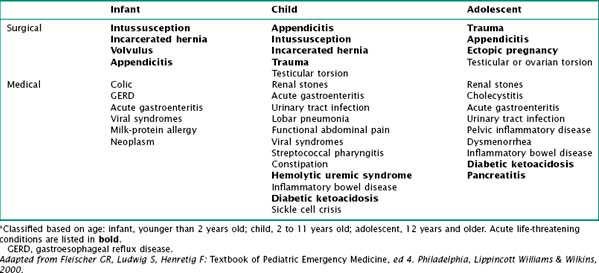

It is helpful to classify the cause of acute abdominal pain by age (Table 5-1). There are many potential causes of abdominal pain, including infectious, anatomic, traumatic, inflammatory, functional, and oncologic.

Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

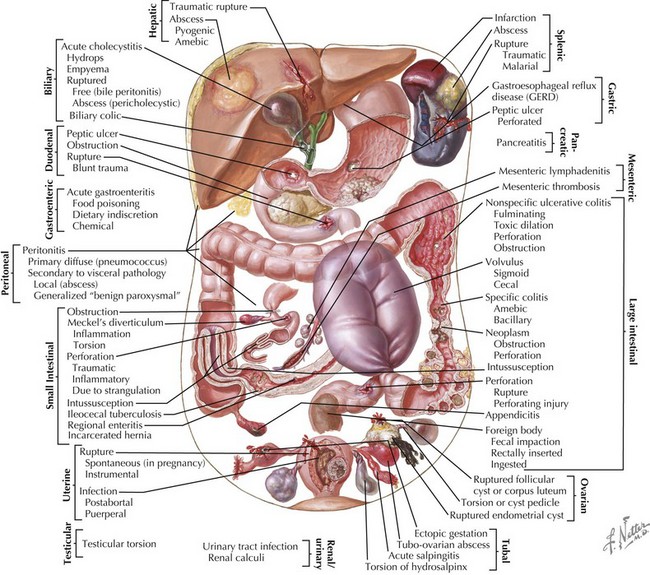

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain in children is very broad, and it can be approached in different ways (Figure 5-2). Certain conditions occur more commonly at specific ages and therefore it may be useful to classify causes of acute abdominal pain based on age. Pain may also be classified as surgical or medical (Table 5-1).

Across all ages, gastroenteritis and appendicitis are the most common medical and surgical causes of acute abdominal pain, respectively. Malrotation with midgut volvulus is the single most devastating abdominal surgical emergency of childhood (see Chapter 109).

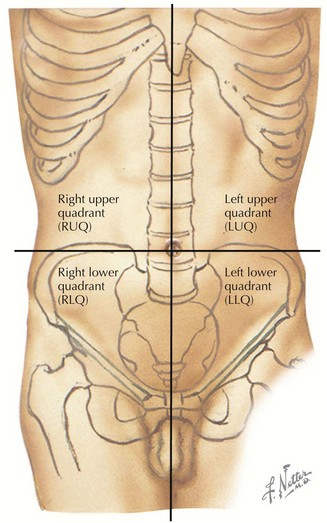

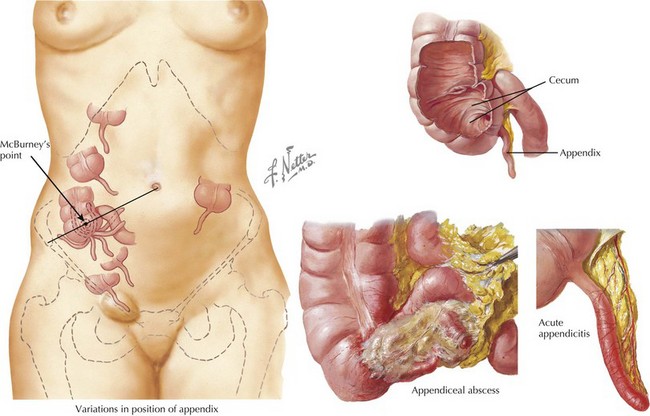

Abdominal pain can also be classified based on the location of the pain. A classic approach is by dividing the abdomen into four quadrants (Figure 5-3). This can help the practitioner direct the workup to rule in or out the most common diagnoses based on the location of symptoms. For example, hepatic and gallbladder disease usually present with right upper quadrant pain (see Chapter 115). Appendicitis classically presents with migration of pain to the RLQ. Gastritis or peptic ulcer disease may present with left upper quadrant pain (see Chapter 108).

Pain Character

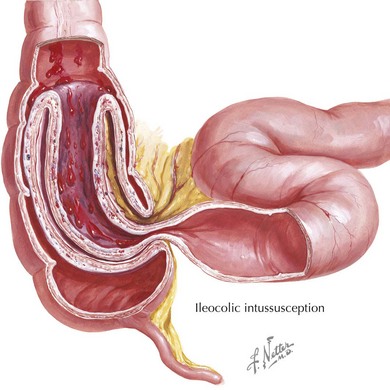

Infants and young children can seldom localize their pain, and parents often describe an inconsolable child who lies with his or her legs drawn up to the chest. Asking the parents if they think the child is in pain can be helpful to distinguish pain from fussiness or irritability. Pain that is intermittent, with paroxysms of cramping inconsolable pain alternating with return to normal state, is characteristic of intussusception (Figure 5-4). Peritoneal irritation is suggested by pain that is worse with movements that change the tension of the abdominal wall, such as a bumpy car ride or walking. Pain that improves after vomiting or a bowel movement reflects a small bowel or large bowel cause, respectively.

The pain of acute appendicitis is progressive in character without intermittent relief. The initial pain of early evolving appendicitis is classically periumbilical. As the inflammatory process progresses to affect the surrounding abdominal wall structures, the pain shifts to the RLQ (Figure 5-5). This progression is very helpful if obtained on history. Patients may describe a sudden temporary decrease in pain, which often coincides with perforation and temporary relief of intraluminal pressure.

Associated Symptoms

Certain infectious processes are associated with abdominal pain: fever, headache, and sore throat suggest streptococcal pharyngitis (see Chapter 35); dysuria and vomiting may be attributable to a urinary tract infection (see Chapter 93); tachypnea and cough point to a lower lobar pneumonia (see Chapter 91). An associated rash may suggest a vasculitis such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura as the cause of the abdominal pain (see Chapter 28). Whereas nonbloody diarrhea suggests gastroenteritis, bloody diarrhea could also signal hemolytic uremic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, or bacterial enteritis. Abdominal pain that is accompanied by vomiting but without diarrhea should prompt a more careful evaluation for potentially life-threatening conditions such as intussusception, midgut volvulus, adhesive small bowel obstruction, or pancreatitis.

Pertinent Medical History

Certain chronic medical conditions are associated with abdominal complications. Patients with sickle cell disease are predisposed to cholecystitis, splenic sequestration, and abdominal vaso-occlusive crises (see Chapter 53). Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with accompanying abdominal pain (see Chapter 4). Patients with Hirschsprung’s disease are at risk for enterocolitis and toxic megacolon, and those with nephrotic syndrome may develop primary bacterial peritonitis. Patients with a history of abdominal surgery are predisposed to adhesions, which may cause obstruction.

Evaluation and Management

The clinician’s first priority is to stabilize patients who are critically ill, focusing on identifying and addressing abnormalities in airway, breathing, and circulation. Next, the clinician must identify potential acutely life-threatening processes requiring emergent surgical intervention (Table 5-1). Typically, these are distinguished based on the patient’s history and physical examination, as discussed previously. Laboratory testing and imaging studies may be useful adjuncts in identifying the diagnosis.

Ashcraft KW. Consultation with the specialist: acute abdominal pain. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:363-366.

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, ed 18. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007.

Fleischer GR, Ludwig S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Leung A, Sigalet D. Acute abdominal pain in children. Am Fam Phys. 2003;67(11):2321-2326.