Chapter 20 Testicular Germ Cell Tumors

Introduction

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy in males ranging from puberty to the fourth decade of life.1

Although the focus of this chapter is on testicular GCTs, it is important to provide an initial overview of GCTs, which include EGGCTs. The most common sites of EGGCTs are the mediastinum, retroperitoneum; less common sites include the pineal gland and sacrococcygeal area. EGGCTs stem from primordial germ cells that failed to migrate properly during embryogenesis. Retroperitoneal GCTs are rarely EGGCTs because most are metastases from a primary testicular tumor. Primary retroperitoneal EGGCTs may be due to an occult gonadal GCT or metachronous primary retroperitoneal and testicular tumors. Both GCTs and EGGCTs share common histopathology and are divided into seminomatous and nonseminomatous types. Both GCTs and EGGCTs also share a similar pattern of age distribution in the 30s.2,3

Testicular GCTs are highly curable, with a 5-year survival rate of more than 95%.1 The death rate from testicular cancer in the United States is less than 400/yr.1,4

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The incidence of GCTs in the United States from 2001 to 2005 was 11.8 per 100,000.1 Approximately 8400 new cases of testicular GCT are diagnosed in the United States each year.1 The incidence is age-dependent: rare before age 5, most common at age 20 to 39, then declining at age 40 onward.5 When the tumors occur in childhood, they predominantly occur in the 4 years and younger age groups.

The incidence in the 20- to 40-year-old age group has doubled over the last three decades.6 From 1976 to 2005, there was an increase of unknown etiology in the incidence in testicular cancer of 1.5% to 2.3%.7–9 Although testicular cancer is common in young males, it still is a rare tumor, estimated at 1% of male malignancies.6 Testicular cancer is the most common solid malignancy in males between 15 and 40 years of age. Therefore, if a man in his late 40s presents with a testicular mass, other diagnoses such as lymphoma or metastases should be considered. Most are unilateral, with approximately 1% to 5% presenting with synchronous or metachronous bilateral tumors.10,11

Testicular cancer is presumed to have a genetic basis. It has a low incidence in black Americans, with a 4.5 times higher prevalence in whites.12 The highest rates are in western and northern Europe and New Zealand.13 Intermediate rates are in the United States.8,14

Risk Factors

Virtually all histopathologic types of GCT have an abnormality in chromosome 12. Postpubertal tumors are aneuploid abnormalities and associated with a gain of the short arm of chromosome arm 12p, which is labeled as i(12p).15 Tumors that stem from prepubertal gonads tend to be diploid abnormalities.5,15–17

Associated risks of developing testicular cancer include intratubular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN), which is testicular carcinoma in situ. If it is not diagnosed and treated, approximately half of all cases will progress to an invasive malignancy.11,18

Testicular microlithiasis can be a risk factor and is further discussed in the “Ultrasound” section.

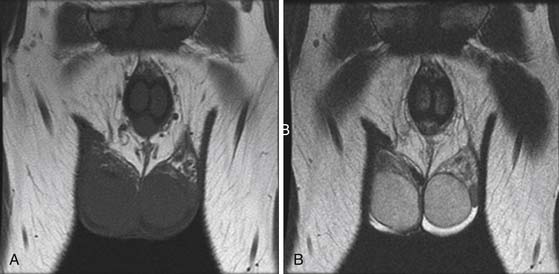

Cryptorchidism is a major risk factor, increasing the risk of germ cell neoplasia 5 to 10 times.19 It is one of the main risk factors that predicts disease occurrence in the testis. The higher the location of the undescended testes, the higher the risk; an abdominal undescended testes has a higher risk than an inguinal undescended testes20 (Figure 20-1). Therefore, it is important to follow-up postorchidopexy patients with a scrotal US. Seminoma accounts for 60% of GCTs with cryptorchidism. The risk factor of developing cancer from cryptorchidism also depends on genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors.19

Another important risk factor is personal past history. Presence of GCT in one testis increases the risk of involvement of the other testis. The 15-year risk of developing a contralateral testicular cancer in affected patients is approximately 1.2%.The incidence of simultaneous bilateral tumors is 1% to 5%.10

Familial history of testicular cancer is a risk factor. Approximately 2% of affected males have a family history, with siblings having up to a 10-fold risk and sons having up to a 6-fold increased risk.21,22

Other associated risk factors are testicular dysgenesis syndromes, which include hypospadias, testicular atrophy, and hypogonadism. Fetal origin testicular cancer is associated with urogenital congenital anomaly, hypospadias, cryptorchidism, and low fetal birthweight.8

Some environmental agents are thought to be associated, including exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) during maternal pregnancy, increased estrogen levels in utero,23 and pesticides.24 Other studies have associated increased risk with dietary factors such as maternal smoking, high cheese diet, and body mass index.17,24

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is another risk factor of increased testicular cancer.23 Others include Klinefelter’s syndrome, dysplastic nevus syndrome, inguinal hernias, and EGGCTs.5

Key Points Epidemiology and risk factors

• Highest incidence is in males 15 to 44 years old.

• Incidence in patients 20 to 40 years old has doubled over the past three decades.

• Common abnormality is in chromosome 12.

• Cryptorchidism is a major risk factor.

• Other risk factors include environmental, personal and family history, and HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

Anatomy and Pathology of the Scrotum and Testes

Anatomy

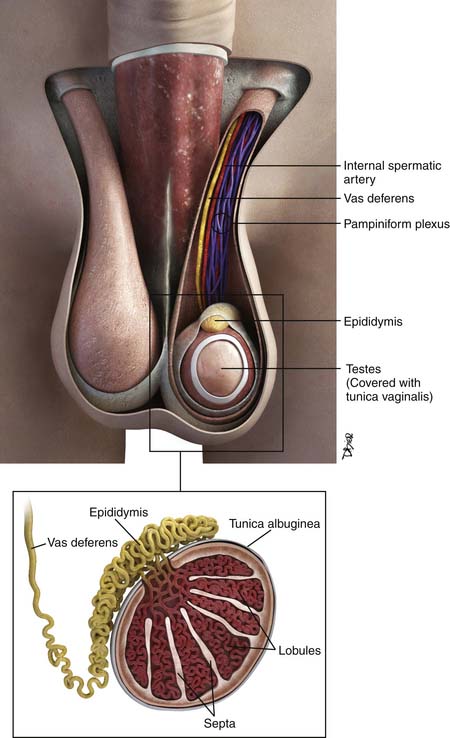

The testes are a component of the scrotum, a pouch that contains the testes, epididymis, and portions of the spermatic cord. Each testis is surrounded by the tunica vaginalis. Surrounding the tunica are fascial layers that compose the scrotal wall. From internally outward, the scrotal wall components are the internal spermatic fascia, the cremasteric muscle, the external spermatic fascia, and the dartos muscle25–27 (Figure 20-2).

Each testis is an elliptical structure containing approximately 400 lobules, which are divided by septa. The septa converge to the mediastum testes, which is contiguous with the tunica albuguinea, a fibrous, dense outer covering of the testis. Each lobule contains two seminiferous tubules, which are lined with germ cells. The seminiferous tubules form a network of ducts known as the rete testis. The ductules connect the rete testis to the head of the epididymis.25–27

The epididymis is composed of a head, body, and tail, from superior to inferior. The body and tail are composed of a single tubule. The tubule joins the vas deferens. The vas deferens courses through the inguinal canal and joins the seminal vesicles to form the ejaculatory duct.25–27

There are several cell types in the testes28:

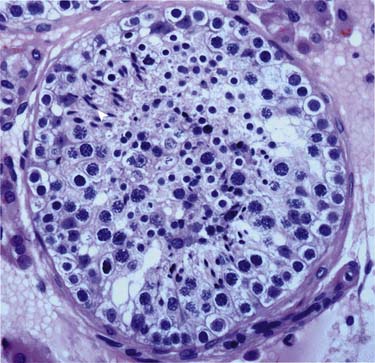

Germ cells (in seminiferous tubules): The germ cells are the precursors to the spermatogenesis process (Figure 20-3).

Sertoli cells (in seminiferous tubules): Located in the epithelium of the seminiferous tubules and play an important process of germ cells developing into spermatozoa.

Leydig cells (in between seminiferous tubules): Important for puberty development; produce testosterone and other androgens.

Other cells: Immature Leydig cells, epithelial cells, and interstitial macrophages.

Pathology

Tumor Types

The vast majority of testicular tumors are GCTs (95%). GCTs originate from spermatogenic cells. GCTs are believed to originate from tissue stem cells and arise from the germinal epithelium of the seminiferous tubules owing to atypical cell proliferation known as testicular intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified (ITGCNU).5,29,30 It is believed that the ITGCNU cells abnormally multiply during puberty, possibly from an altered hormonal environment. The tumors retain stem cell properties, which enable self-renewal that leads to tumorigenesis and differentiation into either seminomatous or nonseminomatous cells, which leads to a varied cellular tumor composition and possible resistance to treatments.17

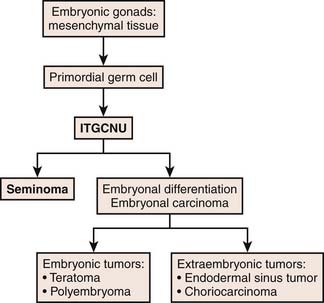

Typically, germ cells arise from the yolk sac during the fourth gestation week and migrate to the gonadal ridge, iliac fossa, and then the scrotum. When there are abnormalities in the migration of these cells, the various types of GCTs arise. Undifferentiated totipotential stem cells give rise to embryonal carcinoma. If the cells continue to progress toward an embryonic pathway, they become teratomas. If they progress to the extraembryonic pathway, they become choriocarcinomas or yolk sac tumors.31 Figure 20-4 describes the histogenesis of GCTs.17

Figure 20-4 Diagram of histogenesis of germ cell tumors.

Redrawn from Cushing B, Perlman E. Germ cell tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2006.

There are two main classifications of GCTs: seminomas and nonseminomas, which compose approximately 95% of malignant testicular tumors. The remainder are lymphomas, which account for 4%; 1% are rare tumors (e.g., interstitial tumors, embryonal sarcomas, and Sertoli cells).13,32

Gross and Microscopic Features

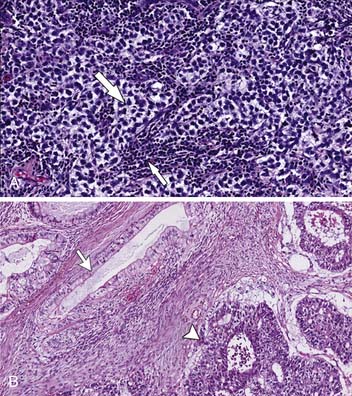

Seminoma

The gross appearance is a homogeneous firm mass with single or multiple nodules. The tumor cells are homogeneous with large round cells with clear cytoplasm in bundles outlined by fibrovascular trabeculae. The bands contain an abundance of plasma cells and T lymphocytes. Granulomatous reaction is common, and hemorrhage and necrosis are rare17,33–35 (Figure 20-5A).

Note that the spermatocytic seminoma is a histologically distinct subtype of seminoma, which is virtually always cured by an orchiectomy and usually no other treatment because it rarely metastasizes.5

Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumors

The NSGCTs include a large group of histologically diverse neoplasms such as embryonal, yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinoma, and teratoma. When one or more tumor components are present, they are mixed. The NSGCTs generally are more ill-defined than seminomas and have hemorrhage and necrosis33,34 (see Figure 20-5B).

• Teratoma: Composed of one or more of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers. Grossly, it is more cystic and multiloculated, sometimes with cartilage. Sebaceous fat and calcifications are typical findings. Immature teratomas have larger solid components with scattered fat and calcification. Different teratomas contain components of nerve, epithelium, and cartilage. The more mature tumors feature differentiated tissue, and the immature teratomas have fetal-based tissues. Histologically, teratomas are predominantly composed of cystic components, with an epithelial lining similar to the epidermis with some appendages. Approximately 85% contain a solid histologically varied element called Rokitansky’s protuberance.17,33,34,36

• Embryonal carcinoma: Gross appearance is that of an ill-defined mass with hemorrhage and necrosis. Vascular invasion can be present. Histologically, the malignant cells are composed of undifferentiated cells with an indistinct border and an anaplastic epithelial and embryonic appearance. The cells are polygonal with atypia and an elevated mitotic rate, proliferating in a tubular, acinar, solid, or papillary appearance.17,33,34

• Yolk sac tumor: Gross appearance is that of a multilobulated solid mass with a mucinous covering, with possible hemorrhage and necrosis. Histologically, it is composed of primitive tumor cells in a loose reticular pattern. Each cell has hyperchromatic nuclei. A distinguishing feature is a Schiller-Duval body, a fibrovascular core containing single vessels.33,34

• Choriocarcinoma: Grossly a heterogeneous mass, commonly identified with hemorrhage and necrosis. Histologically, it is composed of syncytiotrophoblastic and cytotrophoblastic cells.33,34,36,37

• Mixed tumor: A widely varied composition of histologic subtypes; accounts for up to 60% of testicular GCTs.33,34

It is important to note that the presence of yolk sac elements and undifferentiated cells is an important predictor of tumor relapse.38

Two main classifications of germ tumors are present: the World Health Organization (WHO), commonly used in North America and Europe, and the British Testicular Tumor Panel (BTTP), used in the United Kingdom and Australia. The WHO classification is more common and divides tumor categories into seminomatous and nonseminomatous types. The BTTP divides nonseminomatous tumors into different types of teratomas. Table 20-1 differentiates the WHO and BTTP classifications.17,39

Table 20-1 Comparison of the World Health Organization and the British Testicular Tumor Panel Classifications of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors

| BTTP | WHO |

|---|---|

| Seminoma | Seminoma |

| Spermatocytic seminoma | Spermatocytic seminoma |

| Teratoma |

BTTP, British Testicular Tumor Panel; MTI, malignant teratoma intermediate; MTU, malignant teratoma undifferentiated; TD, teratoma differentiated; WHO, World Health Organization; YST, yolk sac tumor.

From Chieffi P, Franco R, Portella G. Molecular and cell biology of testicular germ cell tumors. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;278:277-308.

Key Points Pathology

• Seminomatous GCTs and NSGCTs together are equally divided in prevalence, and together compose approximately 95% of malignant testicular tumors.

• Seminomas are composed of one histologic type and typically are a homogeneous mass with little necrosis or hemorrhage.

• NSGCTs are composed of one or more histologic type with a more heterogeneous appearance, typically with necrosis and hemorrhage.

Tumor Markers

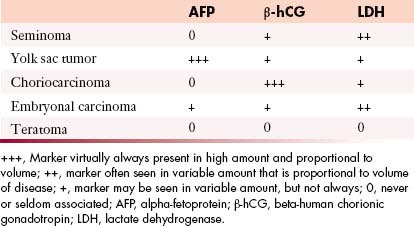

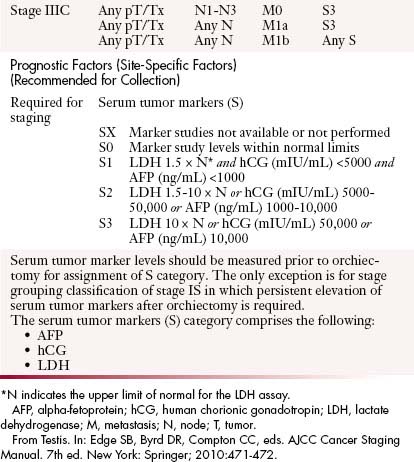

Tumor markers help in the characterization of testicular tumors (Table 20-2).

• Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): Produced by the fetal yolk sac, gastrointestinal tract, and liver. This tumor marker is elevated in 50% to 60% of patients with NSGCTs such as yolk sac tumors and mixed GCTs containing yolk sac elements.17,40,41

• Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG): A glycoprotein produced by syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells. It is elevated in 60% of patients with advanced NSCGTs and in 10% to 20% with stage I disease. Advanced seminomatous disease has elevated hCG in up to 25%. Choriocarcinomas (pure trophoblastic teratomas) have very high levels of hCG and metastasize widely.17,40,41

• Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): A less specific marker because it is produced by multiple organs. It is elevated in greater than 80% of NSCGT cases at the time of initial presentation and is elevated in patients with advanced seminoma. Its levels correlate with the bulk of disease.17,40,41

Clinical Presentation

The most common presentation of testicular cancer patients is a painless testicular mass.42 The clinical presentation is highly variable, such as a palpable testicular mass, pain, and/or swelling. Approximately 10% present with fever and/or scrotal pain.43 Some series have reported that about half of all patients with testicular cancer present with testicular pain with or without a mass. In approximately 20%, symptoms are related to metastatic disease. The patient may also present in the advanced stages with backache from retroperitoneal adenopathy, which should be differentiated from musculoskeletal pain. Other symptoms include neck mass from adenopathy, dyspnea, and hemoptysis from lung metastases or nodal disease in the lungs. Approximately 5% present with gynecomastia. Approximately one in three to four patients presents with abdominal and back pain, headache, malaise, or hemoptysis. The testicular tumor may be an incidental finding secondary to recent trauma in the region, which reveals the finding on further evaluation with imaging or examination.44

If retroperitoneal adenopathy or, less commonly, cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary adenopathy is palpated or detected by US or CT in a male patient, particularly between 15 and 35 years old, a testicular examination and US should be performed to evaluate for an underlying primary tumor.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Blood Supply of Testes

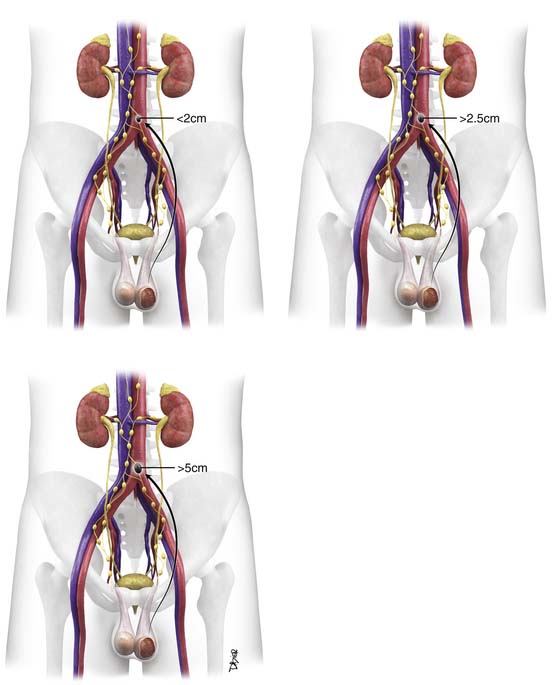

The pair of testicular arteries arises from the aorta. The right testicular artery originates from the abdominal aorta. The left testicular artery originates from the left renal artery. The testicular arteries course through the inguinal canal. The testis features a dual blood supply. These are the cremasteric artery, which is an inferior epigastric artery branch of the external iliac artery, and the artery of the ductus deferens, an inferior vesicle artery branch of the internal iliac artery. The right testicular vein drains into the inferior vena cava (IVC), and the left testicular vein drains into the left renal vein. The lymph node drainage pattern, therefore, predominantly first involves the aortocaval nodes on the right and para-aortic lymph nodes below the renal vasculature on the left.45

Lymphatic Spread

The pattern originates in the mediastinum of the testes, to the internal inguinal ring along the spermatic cords, alongside the lymphatic channels adjacent to the testicular vessels, and to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes.46 This route is based on the embryologic origin of the testes in the retroperitoneum.44

Right-sided nodes have more variability in spread pattern, with preferential spread inferior to the right renal hilum, to the right paracaval, interaortocaval, preaortic, precaval, and retrocaval nodes. Right-sided tumor spreads to right-sided nodes 85% of the time and to contralateral and ipsilateral nodes 13% of the time.13,47,48

Left-sided nodes tend to spread inferior to the left renal vessels to the left para-aortic nodes and preaortic nodes. Left-sided tumor spreads to left-sided nodes 80% of the time and to both contralateral and ipsilateral nodes 20% of the time.13,47,48

The right and left infrarenal periaortic nodes spread to the renal suprahilar nodes and then to the retrocrural nodes. Direct spread can occur through the retroperitoneum to the diaphragm and then to the posterior mediastinal and subcarinal nodes. Indirect spread can occur through the thoracic duct to the prevascular and supraclavicular nodes13,47 (Figure 20-6).

Lymphatic spread can also occur lateral to the aortocaval group to the echeolon node, situated between the first and third lumbar vertebral bodies on the right and anterior to the left iliopsoas muscle on the left.13,49

It is rare to have contralateral nodal metastases without ipsilateral metastatic or primary disease. It is also rare to have direct spread to iliac or inguinal nodes. In the presence of advanced disease, previous scrotal surgery, or cryptorchidism, or at relapse of tumor, pelvic spread and contralateral nodal spread can occur.47 Direct spread to inguinal nodes can occur when there are skin metastases.

Hematogenous Spread

The primary site of hematogenous spread is the lungs.49 Other sites include the brain, which is common with choriocarcinoma. Additional sites include the osseous structures and liver. Rare sites of hematogenous spread include pleura, pericardium, muscle, skin, spleen, kidneys, adrenal glands, and peritoneum.50 Although hematogenous spread is generally associated with synchronous lymph node metastases, it does occasionally “skip” the retroperitoneum in cases of embryonal carcinoma.

Key Points Tumor spread

• Predominant form of tumor spread is through the lymphatics.

• Most common site of metastases is the retroperitoneum, followed by the lungs.

• Direct spread can occur through the retroperitoneum to the diaphragm, then to the posterior mediastinal and subcarinal nodes.

• Indirect spread can occur through the thoracic duct to the prevascular and supraclavicular nodes.

• Hematogenous spread is less common, most often to the lungs.

Staging

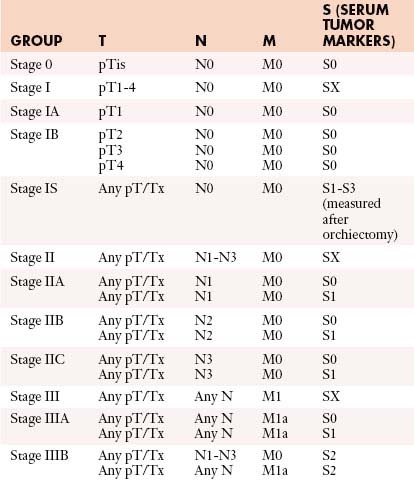

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system is utilized for staging (Figure 20-7).

• Stage I: Disease is confined to the testes with no nodal disease or metastases; consists of IA and IB. IS is persisting elevated tumor markers after orchiectomy.

• Stage II: Disease in the retroperitoneum is confined to lymph nodes. Stage IIA has lymph nodes smaller than 2 cm, stage IIB nodes are 2 to 5 cm, and stage IIC nodes are larger than 5 cm.

• Stage III: Metastases spread beyond the retroperitoneum or to extranodal sites.

Table 20-3 describes the TNM classification of GCTs.51 Table 20-4 lists the staging criteria of GCTs.51

| Primary Tumor (T)* | |

| The extent of primary tumor is usually classified after radical orchiectomy, and for this reason, a pathologic stage is assigned. | |

| pTX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| pT0 | No evidence of primary tumor (e.g., histologic scar in testis) |

| pTis | Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (carcinoma in situ) |

| pT1 | Tumor limited to testis and epididymis without vascular/lymphatic invasion; tumor may invade into tunica albuginea but not tunica vaginalis |

| pT2 | Tumor limited to testis and epididymis with vascular/lymphatic invasion, or tumor extending through tunica albuginea with involvement of tunica vaginalis |

| pT3 | Tumor invades spermatic cord with or without vascular/lymphatic invasion |

| pT4 | Tumor invades scrotum with or without vascular/lymphatic invasion |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| Clinical | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass 2 cm or less in greatest dimension or multiple lymph nodes, none more than 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension or multiple lymph nodes, any one mass greater than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| Pathologic (pN) | |

| pNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| pN0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| pN1 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass 2 cm or less in greatest dimension and less than or equal to five nodes positive, none more than 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| pN2 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension; or more than five nodes positive, none more than 5 cm; or evidence of extranodal extension of tumor |

| pN3 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| M1a | Nonregional nodal or pulmonary metastasis |

| M1b | Distant metastasis other than to nonregional lymph nodes and lung |

* Note: Except for pTis and pT4, extent of primary tumor is classified by radical orchiectomy. TX may be used for other categories in the absence of radical orchiectomy.

From Testis. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010:471-472.

Once the tumor is staged, the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG) recommends that the patient risk be determined using the International Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (IGCCCG) guidelines, which is divided into good, intermediate, and poor categories.52,53 The classification is based on tumor location, metastases, tumor markers, and histology. Table 20-5 lists the IGCCCG guidelines.52,53

Table 20-5 International Germ Cell Consensus and Prognosis Classification

| Seminoma |

| Good prognosis: all of the following |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; N, upper limit of normal.

Adapted from International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594-603.

Poor risk of NSCGT are patients with any one of the following: nonpulmonary visceral metastases such as liver and brain metastases, markedly elevated serum markers (AFP > 10,000 ng/mL or hCG > 50,000 IU/L or LDH > 10 times the upper limit of normal), or mediastinal primary site.54,55

Key Points Staging

• TNM system is widely used to stage testicular tumors. After staging, the IGCCCG guidelines place the patient into good-, intermediate-, and poor-risk categories.

• Stage I is confined to the testis with no nodal disease or metastases.

• Stage II has disease in the retroperitoneum confined to lymph nodes.

• Stage III has metastases that spread beyond the retroperitoneum or to extranodal sites.

Imaging

The diagnosis of testicular carcinoma is usually made after an inguinal orchiectomy and is based on the histopathology.56 Percutaneous biopsy of the testicle can lead to seeding along the biopsy tract, so it is never performed if germ cell malignancy is suspected.57

When interpreting radiologic examinations, it is important to note that important predictors of tumor relapse are lymphatic invasion and vascular invasion.38

Ultrasound

US is the primary modality for assessing the testes, with a greater than 95% sensitivity and specificity for detecting testicular lesions. It can be easily performed and is cost-effective. It is used to screen for associated abnormalities such as contralateral disease and microlithiasis. Typically, a high-frequency linear transducer from 7 to 10 MHz is used with imaging in at least two planes.53

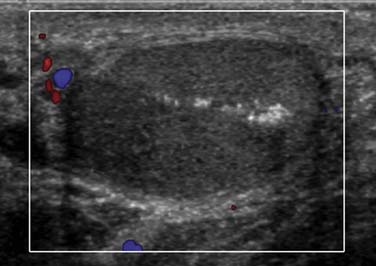

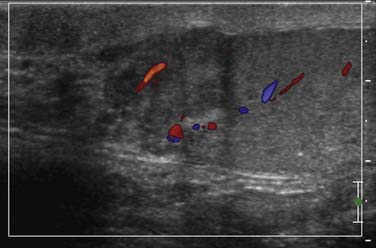

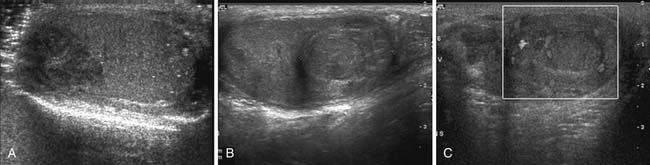

Generally, seminomas have a homogeneous hypoechoic echotexture, and nonseminomas have a more heterogeneous appearance with calcifications and cystic components (Figure 20-8). Some tumors exhibit relatively increased vascularity, although this sign is nonspecific.58 In tumors less than 2 cm, it may be difficult to detect vascularity. It is important to distinguish a mass from focal orchitis, which can also present as a hypoechoic structure with increased vascularity; however, orchitis tends to be more ill-defined than tumors.

Figure 20-8 A, Gray-scale image of a testis demonstrates a hypoechoic relatively well-circumscribed mass, pathologically proven to be seminoma. Note the microlithiasis, which is not as diffuse as in Figure 20-10. Testicular microlithiasis can be an associated risk for developing a testicular malignancy. B and C, Ultrasound (US) image of the testes, gray-scale and color Doppler images. A primary nonseminomatous germ cell tumor measures 2.5 cm in size, with heterogeneous hemorrhage, necrosis, and some vascularity. Pathology reveals 50% choriocarcinoma, 30% yolk sac, and 20% embryonal carcinoma.

A, Courtesy of Dr. F. Eftekhari, Department of Radiology, M. D. Anderson Hospital, Houston, Texas.

A burned-out or regressed GCT is clinically not palpable and is believed to represent a tumor that outgrows its blood supply. It typically presents as a scar at the primary site with metastatic disease. Sonographically, the testes features small hypoechoic or hyperechoic nodules.44 If one suspects a burned-out tumor, it is important to notify the surgeon because the patient may not always have an orchiectomy owing to nonviable tumor (Figure 20-9).

Testicular microlithiasis has benign calcifications within the lumen of the seminiferous tubules and is well-visualized on US. It is defined as five or more punctate calcifications in the US transducer field (Figure 20-10). Testicular microlithiasis might be the only indication of ITGCN, because it is more frequent in patients with ITGCN than in those without. The risk of ITGCN is approximately 20% with bilateral microlithiasis and 0.5% in patients without testicular microlithiasis.59 Testicular microlithiasis is associated with infertility, cryptorchidism, and Down syndrome, among other entities. In patients with known testicular cancer, there is a strong association with microlithiasis.21,60–62 A study found a 48% prevalence of microlithiasis in patients with testicular germ cell cancer, with a 24% prevalence of microlithiasis in a family member of an affected patient.21 Some studies cite the prevalence of microlithiasis in the general population to be approximately 0.6% to 9%.21,63–65 If incidentally detected without any other associated risk factors, microlithiasis in and of itself does not predict the subsequent development of testicular cancer. It affects approximately 2.4% to 14.1% of asymptomatic adult males. In the pediatric population, it is estimated at 1% to 2% in the asymptomatic population. There have been mixed recommendations for how testicular microlithiasis should be followed because serial US examinations are not cost-effective. A new follow-up algorithm suggests that, once testicular microlithiasis is detected, the patient should be assessed for other risk factors (e.g., cryptorchidism, infertility). If the patient is younger than 50 years, a US or testicular biopsy might be performed because the risk of ITGCN is higher in this population.18,66,67 If no other risk factors are present and the patient is older than 50 years, self-examination without US surveillance is suggested. If a biopsy is performed and is negative, no further follow-up is advised.68

Others suggest that screening ultrasounds are not recommended for the population with incidental testicular microlithiasis because they are not cost-effective. Instead, they recommend educating men about self-examination.69 US follow-up is recommended for patients with microlithiasis who cannot proactively perform self-examinations, including the pediatric and adolescent populations.70

Although there are several suggestions for managing microlithiasis, no definite guideline for their management exists.59,71

A US is performed to evaluate for a testicular tumor when a 15- to 40-year-old male presents with retroperitoneal or mediastinal adenopathy or lung metastases. Another useful purpose is to evaluate the contralateral testes for contralateral tumor involvement in a patient with known testicular cancer, which is important because the highest risk of a second malignancy is development of a second primary in the contralateral testes (Figure 20-11).

Computed Tomography

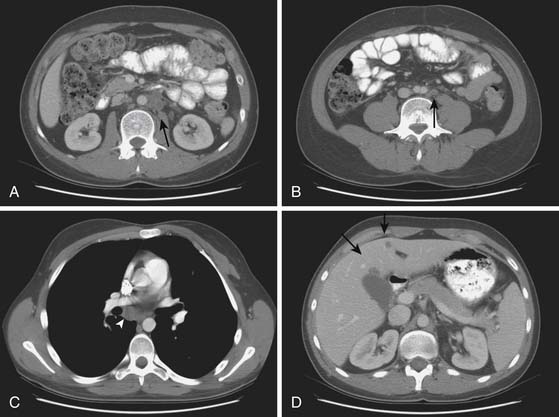

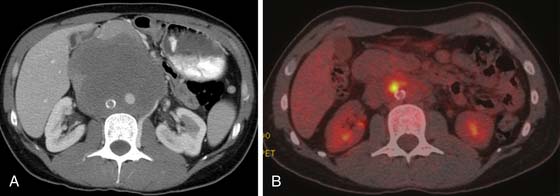

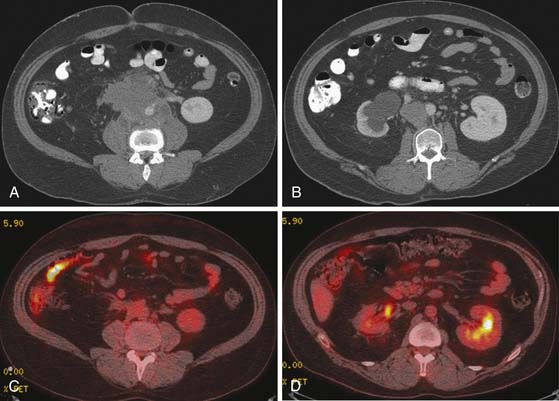

CT is the primary imaging modality for disease staging in testicular cancer patients for disease in the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, with accuracy close to 80%.72 Approximately 38% of testicular cancer patients present with retroperitoneal metastases at the time of initial diagnosis, and CT is a sensitive modality for detecting the adenopathy.

According to the EGCCCG, patients should have a contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.73,74 Within the chest, CT is sensitive for detecting mediastinal and supraclavicular adenopathy, pleural disease, and pleural effusions. Nodal dimensions greater than 10 mm are suspicious based on correlative findings, such as interval enlargement and elevating tumor markers. CT does have limitations because nodal measurements between metastatic and nonmetastatic nodes do overlap. Tumor infiltration into normal-sized nodes is difficult to detect on CT. Finding metastatic nodes is important in the staging of patients because stage I patients undergo surveillance and stage II patients start chemotherapy. Using a 10- to 15-mm short axis as a criteria for metastatic nodes has shown to yield false-negative rates ranging from 29% to 44%. If smaller nodes less than 4 mm are used, sensitivity improves but specificity decreases. CT is not able to identify low-volume nodal disease in approximately 30% of GCT patients.75 Several papers have cited false-negative rates approaching 59% on CT because disease involvement is based on nodal measurement. The false-positive rate of CT has been cited as high as 40%, in which nodes greater than 1 cm short axis may also represent benign reactive nodes from inflammation or hyperplasia.53 An important point to consider is that nodes in the lower retroperitoneum tend to be slightly larger than those in the upper retroperitoneum.76 Although it is difficult to determine malignant nodal disease, as a general consensus, nodes greater than 1 cm short axis are abnormal and those 8 to 10 mm are suspicious.13,53 The size should be correlated with prior examinations, size measurements, tumor markers, and histologic diagnosis.

Vascular anomalies must be differentiated from retroperitoneal disease. Such vascular anomalies include retroaortic renal vein, circumaortic renal vein, IVC variants such as a duplicated IVC or left-sided IVC, or enlarged gonadal veins. In addition, unopacified loops of bowel in the retroperitoneum may simulate soft tissue attenuation retroperitoneal adenopathy. The correct CT scanning technique is important in enabling differentiation. Intravenous contrast will delineate vasculature from nodes. Gastrointestinal contrast will opacify loops of bowel and differentiate from lower-attenuation nodes. The development of spiral CT with thinner sections with up to 5-mm-thick slices has been able to detect smaller nodes that can be easily missed with thicker slices. The ability to scan in or reconstruct thinner slices in questionable regions can increase the sensitivity for detection.13

It is debated whether a CT of the pelvis is useful in patients with testicular cancer. Typically, iliac and inguinal nodes are not involved in stage I cases. Pelvic adenopathy may occur in the presence of bulky retroperitoneal disease or when there has been previous surgery such as inguinal or scrotal surgery, retroperitoneal surgery, or correction of an undescended testes or congenital anomaly.77 Many clinicians do not scan the pelvis in routine surveillance examinations if the patient does not have any of the previous conditions in order to avoid exposing the patient to unnecessary radiation.13,38,78

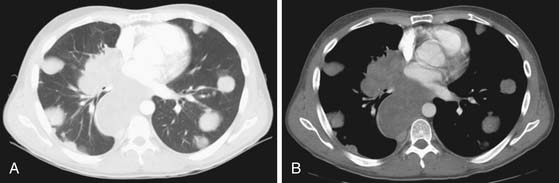

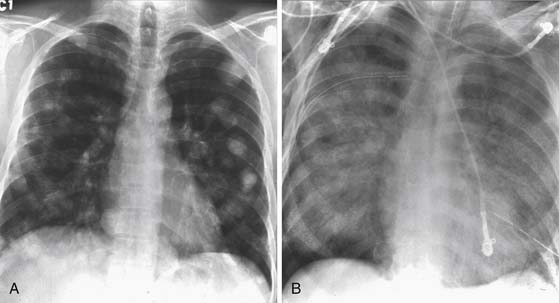

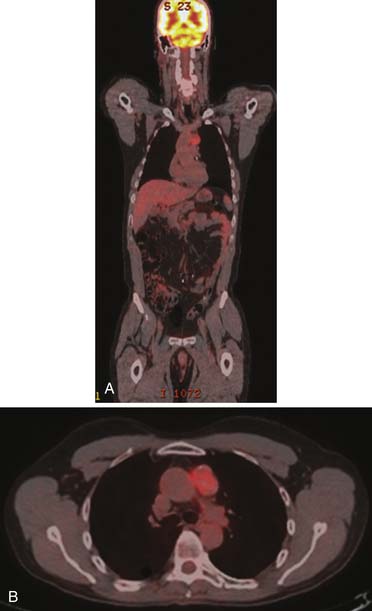

CT of the chest is a well-recognized important examination to obtain to evaluate for nodal disease, lung nodules, pleural effusions, or pleural disease (Figure 20-12). It is common for seminomas to present with pleural disease or pleural effusions.79 In seminomatous disease, there may be direct spread through the diaphragmatic hiatus and into the posterior mediastinum.79 Lung metastases may vary according to histology: seminoma metastases tend to be larger and NSGCT metastases more commonly appear as smaller multiple peripheral nodules.53 In nonseminotomatous disease, spread tends to be in a more random distribution.79,80 Nodal disease in the anterior mediastum, hila, neck, and supraclavicular fossa is more common with NSCGT than with seminomatous disease. Typically, chest nodes rarely occur in the absence of retroperitoneal disease.

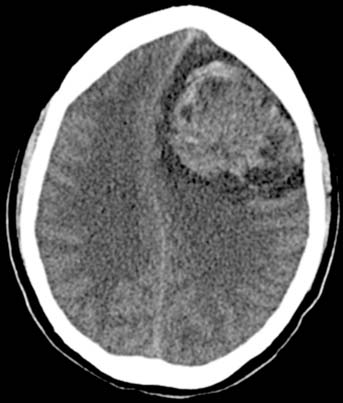

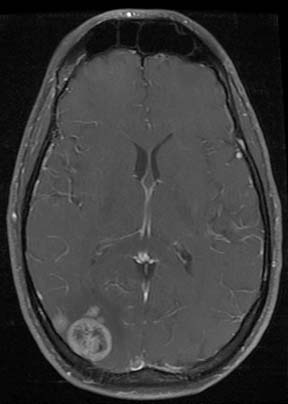

CT of the brain is obtained in high-risk patients to evaluate for hemorrhagic metastases, which manifest as high-attenuation foci on noncontrast scans (Figure 20-13). Alternatively, an MRI may be performed to evaluate the brain.

Plain Chest Radiographs

Chest radiographs provide a baseline for evaluating for mediastinal disease, lung nodules greater than 1 cm, and the presence of pleural effusions or pleural tumor (Figure 20-14). It is a considerably less expensive modality than a chest CT, can be used for monitoring patients in between serial CT examinations and can reduce the radiation dose for a patient receiving multiple CT scans. Chest x-rays are typically utilized in patients with a lower risk, such as patients with seminoma with no retroperitoneal disease, as a screening for lung metastases.81

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is an important problem-solving tool. It is a particularly good modality to assess for metastatic disease in patients who cannot receive a contrast-enhanced CT because it has superior contrast resolution to CT. It is also used in patients who have equivocal findings on CT such as indeterminate liver lesions or osseous lesions that need further characterization.

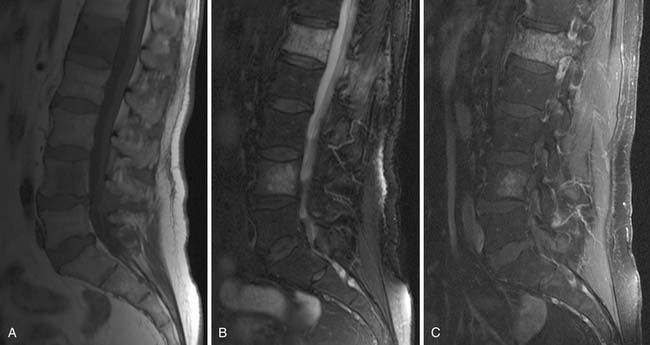

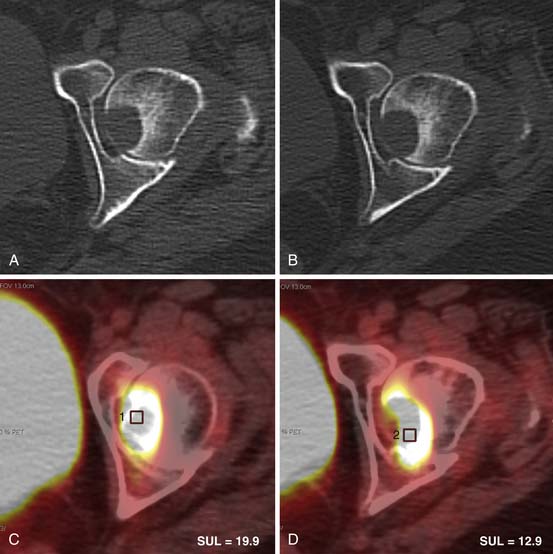

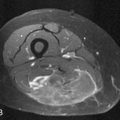

• MRI is superior to CT in assessing the presence of marrow disease.82 Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) MRI is particularly useful for differentiating osseous metastases from pathologic compression fractures or spondylitis, which is important for clinical management of a patient who may present with back pain74 (Figure 20-15).

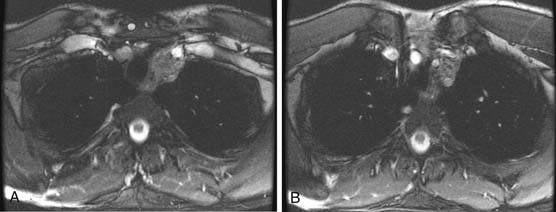

• MRI can delineate vascular invasion. With its multiplanar technique and superior contrast resolution to CT, it is good for delineating vascular anatomy, which is beneficial before retroperitoneal nodal dissection, or to evaluate for tumor invasion of the IVC or upper extremity vessels83 (Figure 20-16).

• MRI is used for assessing neurologic metastatic disease in patients. These include detection of brain, meningeal, and spinal cord involvement.84 A brain MRI is performed as an initial staging device in patients with a high-risk profile. Brain metastases are most common in choriocarcinomas. Central nervous system metastases are found in fewer than 5% of initially staged patients (Figure 20-17).

Another problem-solving function for MRI is to assess for some complications that CT may not visualize, such as the presence of a fistula between a retroperitoneal mass and adjacent bowel or skin.13

MRI is useful in decreasing the radiation dose of patients who need multiple CT scans for surveillance.85 The radiation risk of a CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis single combined examination for developing a second cancer is 1 in 2000; with multiple surveillance scans, this may increase the risk to 1 in 300.85 MRI has been demonstrated to have a similar sensitivity to CT in detecting nodal disease greater than 1 cm in 95% in experienced readers in a study. Currently, a Trial of Imaging and Schedule in Seminoma of the Testis (TRISST) is under way to compare MRI and CT for follow-up. It is a prospective, randomized trial for stage I seminoma patients.85

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequences

Magnetic resonance imaging with lymphotropic nanoparticles (LNMRI) is currently being investigated for differentiating malignant from benign nodes. Initial results indicate that it increases the sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between malignant nodes less than 1 cm from benign nodes greater than 1 cm. The mechanism of lymphatic targeting is based on slow extravasation of nanoparticles into the interstitial space that are transported to lymph nodes and taken up by lymph node macrophages, causing intracellular trapping and signal change in MRI, which enables nodal detection. Preliminary studies have demonstrated a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 92% for detecting nodal metastases in contrast to regular T1 and T2 sequences alone, which have a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 68%. Limitations of the studies include a small sample size, few evaluated nodes, and percutaneous biopsy for pathology evaluation.44,86–88

Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) is under investigation for being used to detect metastatic nodes based on the cellular components of the lymph nodes rather than the nodal size. Normal nodes incorporate the USPIO particles into the reticuloendothelial system, with the supermagnetic effect causing low signal intensity of a normal node. When malignant nodes replace the normal reticuloendothelial elements, they cannot incorporate the USPIO particles, and therefore, their signal intensity is typically higher. A false-negative rate has been reported in small-volume metastatic disease, which tends to incorporate the USPIO particles with resulting falsely low signal nodes.87

Another relatively new application of MRI sequences in oncologic imaging is utilizing the DWI functional sequence for imaging the abdomen and pelvis. DWI sequences measure the amount of random diffusion of water molecules within tissues. Generally, malignant tissue and malignant nodes have restricted diffusion manifested by high signal due to restricted random water molecule motion owing to higher density of cells in malignant tissue. The DWI technique is useful for patients who require a short scan time because it can be acquired rapidly. This sequence has been utilized for many years in neurologic imaging. Its function in oncologic body imaging is currently being investigated, with promising initial findings.89

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Scrotum

When performing an MRI of the scrotum, a 3- to 5-cm surface coil is ideal to visualize the scrotum and contents. The testes can be elevated with draping placed between the thighs. A normal testis has intermediate T1 signal and high T2 signal relative to muscle, with the interdigitating fibrous septa that divide the testes into lobules featuring low signal (Figure 20-18). Intratesticular lesions have lower T2 signal than the surrounding parenchyma.25–27,90

MRI features of testicular tumors do correlate with the histologic features. MRI can be used in certain cases to distinguish seminomas from NSCGTs preoperatively. Seminomas are typically homogeneous signal, isointense to testes on T1, and hypointense on T2. Lower T2 signal bandlike structures correspond to the fibrous septa, which enhance more than the surrounding tumor after gadolinium administration. The presence of a tumor capsule is not useful in differentiating seminomatous from nonseminomatous lesions.32,90–93

Nonseminomas typically have mixed signal, generally iso- to hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2. They contain areas of hemorrhage and necrosis and demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement.32,90–93

Although MRI is helpful in differentiating testicular GCTs, it is not consistently reliable for histologic diagnosis, and surgical biopsy is often recommended to histologically characterize the lesion.44 MRI findings in tumor characterization plays no significant role currently in clinical management because the management protocol mandates an orchiectomy with detailed pathology for tumor classification and initial treatment.

Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

PET has become a more sensitive modality with PET/CT fusion examinations, which combine the functional imaging of PET with the anatomic imaging of CT. PET’s fusion with CT has shown increased accuracy of metastases detection than CT, except small-volume metastases, which are difficult to detect on PET. One study demonstrated that PET sensitivity and specificity were 80% and 100%, in comparison with CT alone, in which the sensitivity was 70% and specificity was 74%.94,95 PET imaging can be shown to alter patient management.

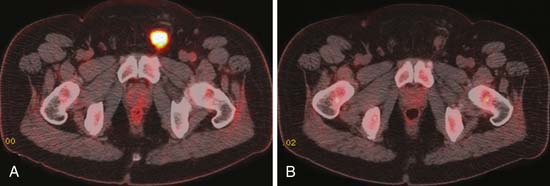

FDG-PET utilizes fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose; malignant cells demonstrate higher uptake of this agent owing to their accelerated metabolism compared with normal cells. Most testicular tumors including seminomatous tumors exhibit high metabolism. Mature well-differentiated teratomas and nonseminomatous metastases typically have less FDG activity (Figure 20-19).

FDG-PET is a promising modality to detect residual disease in postchemotherapy patients, particularly for seminomas, which generally have higher uptake than NSGCTs.94,96,97 Typically, it is recommended to perform FDG-PET after about 2 weeks of therapy. Patients with metastatic nodal disease tend to run a long course with residual masses. PET is of use to reassess for potential recurrence by detecting the metabolic activity in the residual mass (Figures 20-20 to 20-22).

PET imaging is not as useful in NSCGT patients because of mature teratoma, which does not demonstrate significant uptake on PET. It is difficult to differentiate teratoma from posttreatment necrosis. In NSGCT posttreatment residual masses, approximately 55% are residual carcinoma or mature teratoma.95,98 The remainder are only posttreatment necrosis. Mature teratomas need to be surgically excised because they can undergo malignant transformation.99

In seminoma, several studies are in agreement that a negative FDG-PET scan reveals a low likelihood of disease, but false-positive scans can occur. An Indiana University study of postchemotherapy seminoma patients with residual masses demonstrated that a negative PET examination reveals a low likelihood of recurrence, but a positive PET examination does not always indicate residual tumor and may represent fibrosis, necrosis, or inflammation.100,101 The current guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network is to obtain a PET/CT scan in seminoma patients with a residual mass on CT with normal-range tumor serum markers. FDG-avid lesions can then be investigated further with biopsy, and negative lesions can be observed.102

PET may also be of benefit when a patient with seminoma or NSGCT has a raised tumor marker level and no detectable metastases by CT or MRI. A study that supports this identified the site of disease in most positive cases.103 False-negative PET scans were present, which later turned positive on subsequent imaging in three out of five cases. These findings indicate that, when a patient has raised tumor serum markers, a negative CT, and a prior negative FDG-PET, a follow-up FDG-PET still may be useful. Another study questioning the importance of PET in patients with raised tumor levels and no detectable disease was reported by the Medical Research Council (MRC),104 the results of which demonstrated that, although PET did identify some patients with disease not visible on CT, there was a high false-negative rate. It was concluded from this study that FDG-PET does not eliminate the need for continued close surveillance for these patients.

PET may also be of benefit when a patient has a raised tumor marker level and no detectable metastases by CT or MRI. A study that supports this identified the site of disease in most positive cases.103 False-negative PET scans were present, which later turned positive on subsequent imaging in three out of five cases. These findings further validate the point that when a patient has raised tumor serum markers, a negative CT, and a prior negative FDG-PET, a follow-up FDG-PET still may be useful.104

PET is generally not used for initial staging or routine surveillance in patients because there have been studies that demonstrate it does not detect an acceptable amount of relapsed cases sufficiently to be used. A large prospective multicenter study demonstrated a high rate of tumor relapse in patients with negative FDG-PET findings.104,105

Bone Scan

Bone scan, a radionuclide examination, is not commonly performed because bone metastases are not common. A bone scan may be of use when patients have advanced metastatic disease (stage IIIC).56,106

Key Points Radiology report

Scrotal Imaging: Ultrasound and MRI

• Evaluate whether the tumor is intratesticular (highly suspicious for malignancy) or extratesticular (less commonly malignant). Also evaluate whether the lesion is solid or cystic.

• Evaluate mass if homogeneous or heterogeneous, and if there is microlithiasis (if US) or vascularity. Detect other associated findings (e.g., hydrocele).

Abdomen and Pelvic Imaging (CT, MRI, PET/CT)

• Evaluate lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum, > 10 mm short axis are more suspicious.

• Evaluate tumor invasion of IVC and visceral metastases, particularly in liver and sometimes bone.

• Pelvic metastases are generally uncommon unless the patient has advanced bulky disease elsewhere or prior surgery.

Treatment*

The curative treatment of testicular GCTs is a multidisciplinary effort. Inguinal orchiectomy is the standard surgical treatment for control of the primary tumor in cases of seminoma and NSGCT.102 In fact, the final diagnosis of seminoma versus NSGCT is rarely made before the final histopathology study after orchiectomy. Adjuvant radiotherapy to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes is a standard management strategy for clinical stage I seminoma after orchiectomy. Adjuvant chemotherapy is an established option for patients with clinical stage I NSGCT and lymphovascular invasion.107–109 Recent studies have shown, however, that a single course of chemotherapy significantly reduces the risk of recurrence for all patients with clinical stage I GCTs.110–112 This treatment consists of a single injection of carboplatin for patients with pure seminoma and a single course of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) for patients with NSGCT.

Thus, a combined modality approach of surgery followed by brief adjuvant chemotherapy (or adjuvant radiotherapy for seminoma) is increasingly common for patients with clinical stage I testicular GCTs. The overall survival rate for these patients is 98% to 99%.107,108 The survival for patients managed with orchiectomy alone (followed by surveillance) is the same as for those receiving adjuvant treatment,113 but the outcome depends upon patient compliance and continuous access to healthcare services. Surveillance also entails a greater burden of therapy for the subset of patients who ultimately experience a recurrence.

As with stage I GCTs, patients with metastatic GCTs (stage II or III) also have a high cure rate. As discussed previously, patients can be classified as good prognosis, intermediate prognosis, or poor prognosis, according to their clinical features at presentation.52 These prognostic groups have corresponding long-term survival rates of approximately 85%, 75%, and 45%, respectively. Some of these patients are cured with combination chemotherapy alone, but such cure rates would not be possible without the routine and standard use of combined modality treatment: chemotherapy plus surgical consolidation for NSGCT114,115 and chemotherapy plus consolidative radiotherapy for seminoma.116 Surgery is seldom necessary for metastatic sites in pure seminoma because of its exquisite sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation, and postchemotherapy surgery is specifically avoided in seminoma because the residual tissue is densely fibrotic.

Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is surgical removal of the “landing zone” lymph nodes. An accurate staging strategy, its role in primary prevention of recurrence in patients with clinical stage I NSGCT is controversial.108,117,118 Morbidity of RPLND includes sympathetic nerve damage that may lead to retrograde ejaculation and infertility; however, use of a modified surgical template is nerve-sparing and potency-preserving in 90% or more of patients.102,117 An advantage of prophylactic RPLND is that it results in excellent local control for teratoma, which is insensitive to chemotherapy or radiotherapy.118,119 Disadvantages are that patients found to have metastatic GCT in lymph nodes (pathologic stage II) require adjuvant chemotherapy120; hence, they are exposed to “double therapy,” and NSGCT with predominance of embryonal carcinoma has a propensity for hematogenous metastasis, notably to the lungs, which is not controlled by RPLND.121

Patients who do not undergo prophylactic RPLND, even after adjuvant chemotherapy, must undergo periodic CT scanning of the abdomen as surveillance for growing teratoma in the retroperitoneum.108,118 Patients with metastatic NSGCT usually have ipsilateral retroperitoneal lymph nodes involved, and the presence of a residual mass after definitive chemotherapy treatment requires that a postchemotherapy RPLND is performed.122 The purpose is severalfold: (1) to detect persistent germ cell malignancy, (2) to prevent malignant transformation of teratoma, and (3) to remove metastatic teratoma and prevent growing teratoma syndrome.

Growing teratoma syndrome is the development of a mature enlarging teratoma in patients after treatment for an NSGCT. It arises during chemotherapy. Typically, the serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) and AFP laboratory studies are within normal range. The treatment of choice is complete resection, which has a better outcome than radiation and chemotherapy, which are ineffective. Recent data suggest that CDK inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of inoperable growing teratomas.123

For surgical candidates, the postchemotherapy RPLND is a “full bilateral RPLND” as opposed to the modified surgical template discussed previously. A known complication of RPLND is injury to the thoracic duct resulting in chylous ascites.124 Abdominal ascites detected by CT scan in the immediate postoperative period should prompt suspicion of chylous ascites. This condition is rarely fatal and requires a period of bowel rest with total parenteral alimentation.

Chemotherapy

The standard chemotherapy for NSGCT is BEP.102 Bleomycin is associated with a risk of pulmonary toxicity.125,126 Acute and reversible toxicity is common and has the features of pneumonitis.127 Serious and fatal toxicity has the features of progressive pulmonary fibrosis, for which there is no effective treatment other than a lung transplant. Bleomycin continues to be used because of its valuable contribution to the overall outcome in patients with NSGCT, although this is less true for seminoma. In NSGCT, bleomycin is a highly effective drug that does not have the neurotoxicity and bone marrow suppression of cisplatin. Combining bleomycin with cisplatin (and etoposide) achieves greater antitumor effect with manageable toxicity. It is possible to treat metastatic NSGCT without bleomycin, but then it is necessary to use additional drugs that have their own toxicities or to lengthen the duration of chemotherapy (from three courses of BEP to four courses of etoposide and cisplatin, in the case of good-prognosis NSGCT).102 The actual risk of serious, life-threatening pulmonary toxicity after three courses of BEP is approximately 1%.128 Accordingly, this drug is routinely used in the treatment of metastatic GCTs and for adjuvant treatment of clinical stage I NSGCT. For the appearance of pulmonary nodules or infiltrates on a postchemotherapy CT scan, bleomycin toxicity should be included in the differential diagnosis. The risk of bleomycin toxicity increases with age, smoking, preexisting lung disease, and cumulative dose of drug received.

Surveillance

Monitoring Tumor Response

Patients receiving first- or second-line chemotherapy for metastatic GCTs almost always show significant tumor shrinkage.129,130 The notable exception is teratoma, which can appear stable or enlarging despite chemotherapy treatment.131 The small percentage of patients who go on to experience a recurrence of chemotherapy-refractory disease can actually show progression of germ cell malignancy during chemotherapy, usually accompanied by an increase in the serum tumor markers.

For patients with stage II or III NSGCT undergoing initial chemotherapy, the first follow-up scan is routinely done after the second or third cycle. The finding of tumor shrinkage on this CT scan is confirmatory because it is expected to occur, and in most cases, it is already reflected in the declining concentration of serum tumor markers (β-hCG and AFP). The presence or absence of a residual mass (partial response [PR] or complete response [CR]) in the retroperitoneum, lungs, or any other metastatic site at this time point helps the medical oncologist and surgeon begin planning for postchemotherapy surgery. The second follow-up scan is done after the completion of chemotherapy, in most cases, where the total duration of chemotherapy is three or four courses, and this scan confirms whether there is a residual mass in the retroperitoneum (or elsewhere). Poor-prognosis NSGCT can require more than four courses of chemotherapy to reach the maximum response, and additional follow-up CT scans can be done in those cases to assess for further shrinkage versus stability of any measurable lesions.132

Patients with seminoma and bulky metastases also show a brisk response to chemotherapy, but a residual mass is common.116 Radiotherapy for consolidation is done only in selected patients and is usually reserved for those with a residual mass greater than 3 cm.102 Smaller masses can be observed, and the vast majority of these represent scar tissue. Some investigators recommend PET/CT in such cases to determine whether viable tumor is still present.

Key Points Surveillance

• Recommended frequency of follow-up imaging decreases with time elapsed since the completion of treatment.

• Minimum duration of follow-up is 5 years for NSGCTs, and 10 years for seminoma.

• Continued annual or every-2-year surveillance is recommended indefinitely for detection of late recurrences, growing teratoma, second primary malignancies, and other late effects of treatment.

• Chest x-ray: For detection of hematogenous (lung) metastases.

Detection of Recurrence

The majority of patients with metastatic GCTs who undergo treatment are eventually rendered free of disease. For patients with stage II or III disease, the probability of recurrence can be estimated using the clinical features at presentation and the IGCCC system (see Table 20-5).52 Most NSGCT recurrences are detected within 2 to 3 years, and those that are detected more than 2 years after chemotherapy are called late relapse and carry a worse prognosis for salvage.133 Seminoma recurrences can occur up to 10 years after treatment and have similar response to treatment regardless of the time interval.102,108,110,134

Follow-up CT scans are very important for patients with stage II or III seminoma treated with chemotherapy because (1) there is often a residual mass, (2) they do not always receive postchemotherapy radiation or surgery, and (3) recurrences are not usually accompanied by elevated serum tumor markers, as they often are in NSGCT. Conversely, patients with stage II seminoma treated with radiotherapy to the retroperitoneum as the primary treatment have almost no risk of recurrence in the treated field. For these patients, the chest x-ray is especially important for detecting pulmonary recurrence and CT scan of the pelvis for detection of pelvic lymphadenopathy (below the treatment field).110

Complications of Therapy

As noted previously, patients with seminoma do not recur in the radiated field. There is a risk of second malignancy, however, which can be seen more than 25 years after treatment.135 Moreover, the most common second malignancies arise from the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract, within the irradiated field. In a long-term follow-up study of 2707 testicular cancer survivors, the most common second malignancies were stomach, pancreas, urinary bladder, and kidney; the risk was greatest when both radiotherapy and chemotherapy had been given.135

Chemotherapy has a number of long-term risks that are unlikely to show radiographic manifestations. These include cardiovascular disease, infertility, treatment-related leukemia, neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, Reynaud’s phenomenon, and nephrotoxicity.108 Bleomycin-induced lung injury can produce radiographic findings, as noted previously.127 Bleomycin is more commonly used for NSGCT, but published guidelines do include BEP as a treatment for advanced seminoma.102 In addition, clinical stage I NSGCT patients are increasingly regarded as candidates for BEP chemotherapy, so the radiologist should be aware that any patient with a diagnosis of testicular GCT could potentially have received bleomycin.109,111,112

Complications of RPNLD include chylous ascites, as noted previously.124 In addition, hydronephrosis can occur on the basis of surgical injury to the ureter or postoperative retroperitoneal fibrosis and requires the placement of a ureteral stent. Occasional patients have the ipsilateral kidney resected at the time of RPLND owing to encasement of the kidney or ureter by fibrosis, necrotic tumor, or teratoma.

New Therapies

Recent studies have prompted a reassessment of how clinical stage I GCTs are managed. The overall safety and efficacy of one cycle of adjuvant BEP for NSGCT or a single injection of carboplatin for seminoma are such that these options now rival surveillance as the preferred strategy. There is not yet a consensus on this question because adjuvant chemotherapy means that some patients are treated unnecessarily and the life expectancy is just as good with surveillance and treatment at the time of recurrence.109,134 The use of adjuvant radiotherapy for clinical stage I seminoma has already declined, however, owing to the rising acceptance of surveillance as an option and now the availability of adjuvant carboplatin as an alternative. Consequently, there will be a greater need for abdominal CT in patients with seminoma. Those who are on surveillance remain at risk for retroperitoneal recurrence, and the risk continues for 10 years. Patients who have received adjuvant carboplatin have a less than 5% risk of recurrence, but unlike the patients treated with radiotherapy, they can still recur in the retroperitoneum. Published guidelines, therefore, recommend the same follow-up schedule of imaging for carboplatin-treated patients as those on surveillance.102

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDC-SCT) has been studied as a definitive treatment for advanced metastatic GCTs. A phase III study of HDC-SCT versus the standard four courses of BEP in patients with poor- or intermediate-prognosis GCTs showed no significant difference in overall survival, so HDC-SCT is currently used only in the salvage setting.136 A retrospective study from Indiana University suggested that HDC-SCT can be curative as second- or third-line therapy in selected poor-risk patients, but its optimal role still remains controversial.137

Conclusion

Testicular tumors that are predominantly germ cell in origin tend to have a good prognosis because the majority can be curable depending on their tumor type. Radiologic imaging continues to play a vital role in the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of these tumors. Although a vast amount of knowledge is known about this tumor, a lot remains to be learned about its imaging and treatment, with ongoing investigational studies.

1. Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-249.

2. Choyke P.L., Hayes W.S., Sesterhenn I.A. Primary extragonadal germ cell tumors of the retroperitoneum: differentiation of primary and secondary tumors. Radiographics. 1993;13:1365-1375. quiz 1377–1378

3. Schmoll H.J. Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(Suppl 4):265-272.

4. Carver B.S., Serio A.M., Bajorin D., et al. Improved clinical outcome in recent years for men with metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5603-5608.

5. Hayes-Lattin B., Nichols C.R. Testicular cancer: a prototypic tumor of young adults. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:432-438.

6. Cooper D.E., L’Esperance J.O., Christman M.S., Auge B.K. Testis cancer: a 20-year epidemiological review of the experience at a regional military medical facility. J Urol. 2008;180:577-581. discussion 581–582

7. Bray F., Richiardi L., Ekbom A., et al. Trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality in 22 European countries: continuing increases in incidence and declines in mortality. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3099-3111.

8. Manecksha R.P., Fitzpatrick J.M. Epidemiology of testicular cancer. BJU Int. 2009;104:1329-1333.

9. Huyghe E., Matsuda T., Thonneau P. Increasing incidence of testicular cancer worldwide: a review. J Urol. 2003;170:5-11.

10. Tabernero J., Paz-Ares L., Salazar R., et al. Incidence of contralateral germ cell testicular tumors in South Europe: report of the experience at 2 Spanish university hospitals and review of the literature. J Urol. 2004;171:164-167.

11. Sonneveld D.J., Schraffordt Koops H., Sleijfer D.T., Hoekstra H.J. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumours in patients with initial stage I disease: prevalence and prognosis—a single centre’s 30 years’ experience. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1363-1367.

12. Gajendran V.K., Nguyen M., Ellison L.M. Testicular cancer patterns in African-American men. Urology. 2005;66:602-605.

13. Husband J.E., Kow D.M. Testicular germ cell tumors. In: Husband J.E., Reznek R. Imaging in Oncology. 2nd ed. London: Taylor and Francis; 2004:401-427.

14. McGlynn K.A., Cook M.B. Etiologic factors in testicular germ-cell tumors. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1389-1402.

15. van Echten J., Oosterhuis J.W., Looijenga L.H., et al. No recurrent structural abnormalities apart from i(12p) in primary germ cell tumors of the adult testis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;14:133-144.

16. Bosl G.J., Ilson D.H., Rodriguez E., et al. Clinical relevance of the i(12p) marker chromosome in germ cell tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:349-355.

17. Chieffi P., Franco R., Portella G. Molecular and cell biology of testicular germ cell tumors. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol.. 2009;278:277-308.

18. Hoei-Hansen C.E., Rajpert-De Meyts E., Daugaard G., Skakkebaek N.E. Carcinoma in situ testis, the progenitor of testicular germ cell tumours: a clinical review. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:863-868.

19. La Vignera S., Calogero A.E., Condorelli R., et al. Cryptorchidism and its long-term complications. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.. 2009;13:351-356.

20. Giwercman A., Bruun E., Frimodt-Moller C., Skakkebaek N.E. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1989;142:998-1001. discussion 1001–1002

21. Korde L.A., Premkumar A., Mueller C., et al. Increased prevalence of testicular microlithiasis in men with familial testicular cancer and their relatives. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1748-1753.

22. Hemminki K., Li X. Familial risk in testicular cancer as a clue to a heritable and environmental aetiology. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1765-1770.

23. Hentrich M.U., Brack N.G., Schmid P., et al. Testicular germ cell tumors in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Cancer. 1996;77:2109-2116.

24. Dieckmann K.P., Hartmann J.T., Classen J., et al. Is increased body mass index associated with the incidence of testicular germ cell cancer? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:731-738.

25. Fritzsche P.J., Wilbur M.J. The male pelvis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1989;10:11-28.

26. Banson M.L. Normal MR anatomy and techniques for imaging of the male pelvis. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am.. 1996;4:481-496.

27. Schnall M. Magnetic resonance imaging of the scrotum. Semin Roentgenol. 1993;28:19-30.

28. McCarrey J.R. Development of the germ cell. In: Desjardins C., Ewing E. Cell and Molecular Biology of the Testis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993:58-89.

29. Skakkebaek N.E., Berthelsen J.G., Giwercman A., Muller J. Carcinoma-in-situ of the testis: possible origin from gonocytes and precursor of all types of germ cell tumours except spermatocytoma. Int J Androl. 1987;10:19-28.

30. Wicha M.S., Liu S., Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea–a paradigm shift. Cancer Res.. 2006;66:1883-1890. discussion 1895–1896

31. Urogenital system. In: Moore K., editor. The Developing Human. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:287-328.

32. Johnson J.O., Mattrey R.F., Phillipson J. Differentiation of seminomatous from nonseminomatous testicular tumors with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:539-543.

33. Tumors of germ cell origin. In: Mostofi F.K., Price E.B. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Male Genital System. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1973. :vol. 8

34. Ueno T., Tanaka Y.O., Nagata M., et al. Spectrum of germ cell tumors: from head to toe. Radiographics. 2004;24:387-404.

35. Ulbricht T.M. Testicular and paratesticular tumors. In: Carter D., Greenson J.K. Sternberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2004:2132-2167.

36. Ulbright T.M. Germ cell tumors of the gonads: a selective review emphasizing problems in differential diagnosis, newly appreciated, and controversial issues. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl 2):S61-S79.

37. Bahrami A., Ro J.Y., Ayala A.G. An overview of testicular germ cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1267-1280.

38. Sohaib S.A., Husband J. Surveillance in testicular cancer: who, when, what and how? Cancer Imaging. 2007;7:145-147.

39. Theaker J.M., Mead G.M. Diagnostic pitfalls in the histopathological diagnosis of testicular germ cell tumours. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2004;10:220-228.

40. von Eyben F.E. Laboratory markers and germ cell tumors. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:377-427.

41. Mason M.D. Tumour markers. In: Horwich A., editor. Testicular Cancer: Investigation and Management. London: Chapman and Hall; 1996:33-43.

42. Carver B.S., Sheinfeld J. Germ cell tumors of the testis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:871-880.

43. Guthrie J.A., Fowler R.C. Ultrasound diagnosis of testicular tumours presenting as epididymal disease. Clin Radiol. 1992;46:397-400.

44. Hilton S. Contemporary radiological imaging of testicular cancer. BJU Int. 2009;104:1339-1345.

45. Husband J.E., Kow D.M. Testicular germ cell tumors. In: Husband J.E., Reznek R. Imaging in Oncology. London: Taylor and Francis; 2004:401-427.

46. Sohaib S.A., Koh D.M., Husband J.E. The role of imaging in the diagnosis, staging, and management of testicular cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:387-395.

47. McMahon C.J., Rofsky N.M., Pedrosa I. Lymphatic metastases from pelvic tumors: anatomic classification, characterization, and staging. Radiology. 2010;254:31-46.

48. Dixon A.K., Ellis M., Sikora K. Computed tomography of testicular tumours: distribution of abdominal lymphadenopathy. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:519-523.

49. Williams M.P., Cook J.V., Duchesne G.M. Psoas nodes—an overlooked site of metastasis from testicular tumours. Clin Radiol. 1989;40:607-609.

50. Husband J.E., Bellamy E.A. Unusual thoracoabdominal sites of metastases in testicular tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:1165-1171.

51. Edge S.B., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed., New York: Springer, 2010.

52. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594-603.

53. Dalal P.U., Sohaib S.A., Huddart R. Imaging of testicular germ cell tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:124-134.

54. Bokemeyer C., Nowak P., Haupt A., et al. Treatment of brain metastases in patients with testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1449-1454.

55. Bajorin D., Katz A., Chan E., et al. Comparison of criteria for assigning germ cell tumor patients to “good risk” and “poor risk” studies. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:786-792.

56. Huddart R., Kataja V. Mixed or non-seminomatous germ-cell tumors: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 2):ii52-ii54.

57. Coakley F.V., Hricak H., Presti J.C.Jr. Imaging and management of atypical testicular masses. Urol Clin North Am.. 1998;25:375-388.

58. Horstman W.G., Melson G.L., Middleton W.D., Andriole G.L. Testicular tumors: findings with color Doppler US. Radiology. 1992;185:733-737.

59. Meissner A., Mamoulakis C., de la Rosette J.J., Pes M.P. Clinical update on testicular microlithiasis. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:615-618.

60. Yagci C., Ozcan H., Aytac S., et al. Testicular microlithiasis associated with seminoma: gray-scale and color Doppler ultrasound findings. Urol Int. 1996;57:255-258.

61. Miller F.N., Sidhu P.S. Does testicular microlithiasis matter? A review. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:883-890.

62. Coffey J., Huddart R.A., Elliott F., et al. Testicular microlithiasis as a familial risk factor for testicular germ cell tumour. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1701-1706.

63. Serter S., Gumus B., Unlu M., et al. Prevalence of testicular microlithiasis in an asymptomatic population. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40:212-214.

64. Peterson A.C., Bauman J.M., Light D.E., et al. The prevalence of testicular microlithiasis in an asymptomatic population of men 18 to 35 years old. J Urol. 2001;166:2061-2064.

65. Bach A.M., Hann L.E., Hadar O., et al. Testicular microlithiasis: what is its association with testicular cancer? Radiology. 2001;220:70-75.

66. Dieckmann K.P., Skakkebaek N.E. Carcinoma in situ of the testis: review of biological and clinical features. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:815-822.

67. Krege S., Beyer J., Souchon R., et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus group (EGCCCG): part I. Eur Urol. 2008;53:478-496.

68. Elzinga-Tinke J.E., Sirre M.E., Looijenga L.H., et al. The predictive value of testicular ultrasound abnormalities for carcinoma in situ of the testis in men at risk for testicular cancer. Int J Androl. 2010;33:597-603.

69. DeCastro B.J., Peterson A.C., Costabile R.A. A 5-year follow-up study of asymptomatic men with testicular microlithiasis. J Urol. 2008;179:1420-1423. discussion 1423

70. Slaughenhoupt B., Kadlec A., Schrepferman C. Testicular microlithiasis preceding metastatic mixed germ cell tumor—first pediatric report and recommended management of testicular microlithiasis in the pediatric population. Urology. 2009;73:1029-1031.

71. Albrecht W. Words of wisdom. Re: a 5-year follow-up study of asymptomatic men with testicular microlithiasis. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1199.

72. Fernandez E.B., Moul J.W., Foley J.P., et al. Retroperitoneal imaging with third and fourth generation computed axial tomography in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Urology. 1994;44:548-552.

73. Schmoll H.J., Souchon R., Krege S., et al. European consensus on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG). Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1377-1399.

74. Ozan E., Oztekin O., Kozacioglu Z., et al. Metastatic testicular germ cell tumor presenting with abdominal pain: CT and MRI findings. JBR-BTR. 2009;92:256-258.

75. Freedman L.S., Parkinson M.C., Jones W.G., et al. Histopathology in the prediction of relapse of patients with stage I testicular teratoma treated by orchidectomy alone. Lancet. 1987;2:294-298.

76. Dorfman R.E., Alpern M.B., Gross B.H., Sandler M.A. Upper abdominal lymph nodes: criteria for normal size determined with CT. Radiology. 1991;180:319-322.

77. Mason M.D., Featherstone T., Olliff J., Horwich A. Inguinal and iliac lymph node involvement in germ cell tumours of the testis: implications for radiological investigation and for therapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1991;3:147-150.

78. White P.M., Howard G.C., Best J.J., Wright A.R. The role of computed tomographic examination of the pelvis in the management of testicular germ cell tumours. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:124-129.

79. Williams M.P., Husband J.E., Heron C.W. Intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic testicular seminoma: a comparison of chest radiographic and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:473-475.

80. Wood A., Robson N., Tung K., Mead G. Patterns of supradiaphragmatic metastases in testicular germ cell tumours. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:273-276.

81. Steinfeld A.D. Testicular germ cell tumors: review of contemporary evaluation and management. Radiology. 1990;175:603-606.

82. Daffner R.H., Lupetin A.R., Dash N., et al. MRI in the detection of malignant infiltration of bone marrow. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:353-358.

83. Ng C.S., Husband J.E., Padhani A.R., et al. Evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging of the inferior vena cava in patients with non-seminomatous germ cell tumours of the testis metastatic to the retroperitoneum. Br J Urol. 1997;79:942-951.

84. Arnold P.M., Morgan C.J., Morantz R.A., et al. Metastatic testicular cancer presenting as spinal cord compression: report of two cases. Surg Neurol. 2000;54:27-33.

85. Sohaib S.A., Koh D.M., Barbachano Y., et al. Prospective assessment of MRI for imaging retroperitoneal metastases from testicular germ cell tumours. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:362-367.

86. Harisinghani M.G., Saini S., Weissleder R., et al. MR lymphangiography using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide in patients with primary abdominal and pelvic malignancies: radiographic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1347-1351.

87. Pandharipande P.V., Mora J.T., Uppot R.N., et al. Lymphotropic nanoparticle-enhanced MRI for independent prediction of lymph node malignancy: a logistic regression model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W230-W237.

88. Harisinghani M.G., Saksena M., Ross R.W., et al. A pilot study of lymphotrophic nanoparticle-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging technique in early stage testicular cancer: a new method for noninvasive lymph node evaluation. Urology. 2005;66:1066-1071.

89. Alibek S., Cavallaro A., Aplas A., et al. Diffusion weighted imaging of pediatric and adolescent malignancies with regard to detection and delineation: initial experience. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:866-871.

90. Schultz-Lampel D., Bogaert G., Thuroff J.W., et al. MRI for evaluation of scrotal pathology. Urol Res.. 1991;19:289-292.

91. Rholl K.S., Lee J.K., Ling D., et al. MR imaging of the scrotum with a high-resolution surface coil. Radiology. 1987;163:99-103.

92. Seidenwurm D., Smathers R.L., Lo R.K., et al. Testes and scrotum: MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology. 1987;164:393-398.

93. Tsili A.C., Tsampoulas C., Giannakopoulos X., et al. MRI in the histologic characterization of testicular neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:W331-W337.

94. De Santis M., Becherer A., Bokemeyer C., et al. 2-18fluoro-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography is a reliable predictor for viable tumor in postchemotherapy seminoma: an update of the prospective multicentric SEMPET trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1034-1039.

95. Basu S., Rubello D. PET imaging in the management of tumors of testis and ovary: current thinking and future directions. Minerva Endocrinol. 2008;33:229-256.

96. Cremerius U., Effert P.J., Adam G., et al. FDG PET for detection and therapy control of metastatic germ cell tumor. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:815-822.

97. Becherer A., De Santis M., Karanikas G., et al. FDG PET is superior to CT in the prediction of viable tumour in post-chemotherapy seminoma residuals. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:284-288.

98. Oechsle K., Hartmann M., Brenner W., et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors after chemotherapy: the German multicenter positron emission tomography study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5930-5935.

99. Hartmann J.T., Schmoll H.J., Kuczyk M.A., et al. Postchemotherapy resections of residual masses from metastatic non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:531-538.

100. Ganjoo K.N., Chan R.J., Sharma M., Einhorn L.H. Positron emission tomography scans in the evaluation of postchemotherapy residual masses in patients with seminoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3457-3460.