CHAPTER 16 Tendoscopy

To become familiar with the endoscopic techniques used in foot and ankle surgery, surgeons can train in a cadaveric setting through international courses that are offered annually.1,2 Tendoscopy can be performed for the diagnosis and treatment of pathologic conditions of the peroneal tendons, the posterior tibial tendon, and the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon. These endoscopic procedures and their indications are discussed in this chapter.

TENDOSCOPY OF THE PERONEAL TENDONS

Peroneal tendon pathology frequently coexists with or results from chronic lateral ankle instability. These disorders often cause chronic ankle pain in runners and ballet dancers.3 Post-traumatic lateral ankle pain is common, but peroneal tendon pathology is not always recognized as a cause of these symptoms. In a study by Dombek and coworkers, only 60% of peroneal tendon disorders were accurately diagnosed at the first clinical evaluation.4

Pathology consists of tenosynovitis, tendon dislocation or subluxation, and (subtotal) rupture or snapping of one or both of the peroneal tendons. It accounts for most symptoms at the posterolateral aspect of the ankle. Other causes of posterolateral ankle pain are rheumatoid synovitis, bony spurs, calcifications or ossicles, pathology of the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), or disorders of the posterior compartment of the subtalar joint. Posterior ankle impingement can manifest as posterolateral ankle pain.5

The primary indication for treating pathology of the peroneal tendons is pain.6 If conservative treatment fails, the surgical intervention involves débridement of the tendons, fibular groove deepening in case of recurrent peroneal tendon dislocation, and an adequate and precise determination of the location and extent of tendon ruptures. Van Dijk introduced a tendoscopic approach to treat a wide variety of peroneal tendon disorders, and the subsequent patient follow-up was published in 2006.7 The tendoscopic technique is safe and produces good or excellent clinical outcomes, making it a good alternative to open surgical approaches.

Anatomy

The peroneal muscles are located in the lateral compartment of the leg, also known as the peroneal compartment. Both muscles are innervated by the superficial peroneal nerve and the peroneal, and medial tarsal arteries supply the muscles with blood through separate vinculae.8,9 The peroneus brevis tendon is situated dorsomedial to the peroneus longus tendon from its proximal aspect up to the fibular tip, where it is relatively flat. Just distal to this lateral malleolus tip, the peroneus brevis tendon becomes rounder and crosses the round peroneus longus tendon. The distal posterolateral part of the fibula forms a sliding channel for the two peroneal tendons. This malleolar groove is formed by a periosteal cushion of fibrocartilage that covers the bony groove.10 Posterolaterally, the tendons are held into position by the superior peroneal retinaculum.7,11

The peroneal tendons act as lateral ankle stabilizers. In chronic ankle instability, more strain is put on these tendons, resulting in hypertrophic tendinopathy, tenosynovitis, and ultimately in tendon tears.7

In 1803, Monteggia was the first to describe peroneal tendon dislocation in a female ballet dancer.12 These tendons dislocate if the superior peroneal retinaculum ruptures, frequently because of an inversion or dorsiflexion trauma of the foot with the muscles contracted, or if it is congenitally absent or weak.11 A nonconcave fibular groove predisposes to dislocation. The cartilaginous rim, located laterally from the fibular groove, adds to the overall depth of the groove.13 If this rim is absent or flat, the tendons are more likely to dislocate.14

Patient Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

Tendinopathy of the peroneal tendons often coexists with a lateral ankle sprain, and the diagnosis of peroneal tendon pathology in a patient with lateral ankle pain can be difficult.15 The anterior drawer test and varus stress test are applied routinely to detect laxity of the ankle ligaments. In acute cases, the detailed history should include reconstruction of the trauma mechanism. The presence of associated conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, hyperparathyroidism, diabetic neuropathy, calcaneal fracture, fluoroquinolone use, and local steroid injections is important, because they can increase the degree of peroneal tendon dysfunction.16 The differential diagnosis includes fatigue fractures or fractures of the fibula, posterior impingement of the ankle, and lesions of the lateral ligament complex. Post-traumatic or postoperative adhesions and irregularities of the posterior aspect of the fibula (i.e., peroneal groove) also can be responsible for symptoms in this region.

Patients with peroneal tendon dislocation typically complain of lateral instability, giving way, and sometimes a popping or snapping sensation over the lateral aspect of their ankle. On physical examination, the tendons can be subluxated by active dorsiflexion and eversion, which provokes the pain.17

Diagnostic Imaging

Peroneal tendon dislocation is a clinical diagnosis, and it is frequently accompanied by a tendon rupture. Additional investigations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography may be helpful in diagnosing partial tears of the tendon of peroneus brevis or longus.18 Both modalities are considerably accurate and precise, although ultrasonography is more cost effective.19

Treatment

Conservative Management

Conservative management should be attempted first. This includes activity modification, footwear changes, temporary immobilization, and corticosteroid injections. Lateral heel wedges can take the strain off the peroneal tendons, which may allow healing.16

Surgical Technique

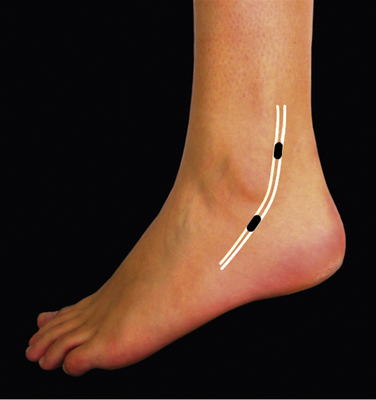

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. Alternatively, the patient can be placed in the supine position with the foot in endorotation. A support can be placed under the leg, allowing the ankle to be moved freely. Before anesthesia is administered, the patient is asked to evert the foot so that the peroneal tendons can be visualized clearly. Their course is drawn on the skin, and the locations of the portals are marked (Fig. 16-1). The surgery can be performed under local, regional, epidural, or general anesthesia. After exsanguination, a tourniquet is inflated around the thigh of the affected leg.

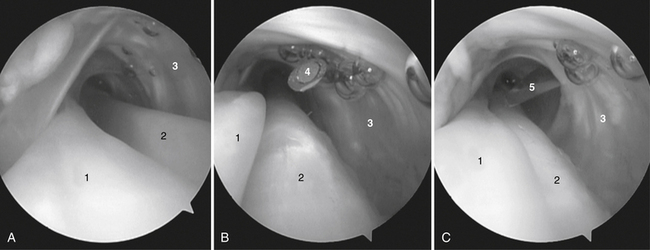

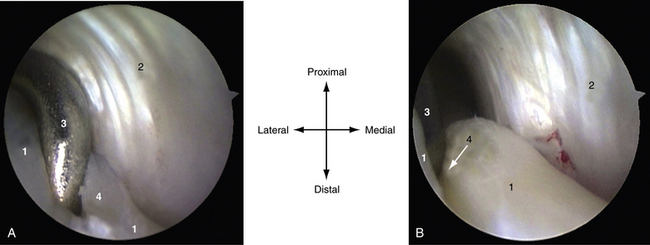

The inspection starts approximately 6 cm proximal to the posterior tip of the fibula, where a thin membrane splits the tendon compartment into two separate tendon chambers. More distally, the tendons lie in one compartment. A second portal is made 2 to 2.5 cm proximal to the posterior edge of the lateral malleolus under direct vision by placing a spinal needle directly over the tendons (Fig. 16-2). Through the distal portal, a complete overview of both tendons can be obtained.

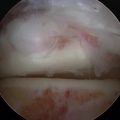

By rotating the arthroscope over and between both tendons, the entire compartment can be inspected (Fig. 16-3). When a total synovectomy of the tendon sheath has to be performed, it is advisable to make a third portal more distal or more proximal than the portals described previously. When a rupture of one of the tendons is seen, endoscopic synovectomy is performed, and the rupture is repaired through a mini-open approach.

In patients with recurrent dislocation of the peroneal tendon, endoscopic fibular groove deepening can be performed through this tendoscopic approach. It is a time-consuming procedure because of the limited working area. Groove deepening is performed from within the tendon sheath, with the risk of iatrogenic damage to the tendons. We therefore prefer an approach based on the two-portal hindfoot technique, with an additional portal located 4 cm proximal to the posterolateral portal.20

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

TENDOSCOPY OF THE POSTERIOR TIBIAL TENDON

These disorders can be divided in two groups: the younger group of patients, who had dysfunction of the tendon caused by some form of systemic inflammatory disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), and an older group of patients, whose tendon dysfunction is mostly caused by chronic overuse.21 After trauma, surgery, and fractures, adhesions and irregularity of the posterior aspect of the tibia can be responsible for symptoms in this region.

A dysfunctional posterior tibial tendon usually evolves to painful tenosynovitis. Tenosynovitis is also a common extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis, in which hindfoot problems are a significant cause of disability. Tenosynovitis in rheumatoid patients eventually leads to a ruptured tendon.22

Anatomy

The posterior tibial muscle arises from the interosseous membrane and the proximal adjacent surfaces of the tibia and fibula, and it is part of the deep posterior compartment of the calf. The tendon forms in the distal third of the calf and passes behind the medial malleolus, where it changes direction.23 The posterior tibial tendon is the most superficial structure coursing directly behind the medial malleolus.

Pain complaints are often localized in the relative hypovascular zone immediately distal to the medial malleolus, beginning 4 cm proximal to the insertion of the tendon.24 This hypovascular zone may contribute to the development of degenerative changes and consequently to ruptures.25

The posterior tibial tendon is held in the retromalleolar groove by a strong fibro-osseous tunnel and the flexor retinaculum originating from the tip of the medial malleolus and inserting into the calcaneus. Distally, the retinaculum blends with the sheath of the tendon and the superficial deltoid ligament.23 The anterior, major slip of the tendon inserts primarily into the tuberosity of the navicular, the inferior capsule of the medial naviculocuneiform joint, and the inferior surface of the medial cuneiform. A second slip extends to the plantar surfaces of the cuneiforms and the bases of the second, third, and fourth metatarsals.23

A tendon sheath surrounds the posterior tibial tendon, and both structures are connected by a vincula, which carries part of the blood supply to the tendon. A vincula can become symptomatic when damaged, causing thickening, shortening, and scarring of the distal free edge. In these patients, a painful local thickening can be palpated posterior and just proximal to the tip of the medial malleolus.25

Patient Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

In the early stage of dysfunction, patients complain of persistent ankle pain medially along the course of the tendon, fatigue, and aching on the medial plantar aspect of the ankle. Tenosynovitis commonly is associated with swelling.23,25 A typical observation is abnormal wear of the medial sides of the shoes. Walking increases pain, and participation in sports activities becomes difficult.

Careful clinical examination is important, and both feet should be examined. Valgus angulation of the hindfoot is frequently seen with accompanying abduction of the forefoot (i.e., too many toes sign).23 The sign is positive when inspecting the patient’s foot from behind; in the case of significant forefoot abduction, three or more toes are visible lateral to the calcaneus, whereas normally, only one or two toes are seen. With the patient seated, the strength of the tendon and location of pain are evaluated by asking the patient to invert the foot against resistance (Fig. 16-4).

Diagnostic Imaging

After initial history taking and physical examination, the diagnosis can be confirmed or rejected using radiography. Conventional radiographs may show abnormal alignment such as flattening of the plantar arch or bony changes such as irregularity and hypertrophic change at the navicular attachment, providing an important clue to long-standing problems with the posterior tibial tendon.26 However, pathology of this soft tissue structure is easier to identify using ultrasound or MRI. Ultrasound imaging is a cost-effective and accurate method for evaluating disorders of the posterior tibial tendon.27 Thickening of the tendon or peritendinous soft tissue, hypoechoic texture, ill-definition of the fibrillar pattern, associated hypervascularity on color Doppler, thinning, splitting, and rupture may be useful clues.26 In our practice, MRI is the method of choice because the images can be interpreted by the orthopedist, in contrast to ultrasound images, and it is therefore more helpful for preoperative planning. It is also considered the gold standard for assessing tibialis posterior dysfunction and related soft tissue injuries.26 A major advantage is the ability to detect bony edema. Findings may include fluid or synovitis around the tendon, hypertrophy of the tendon, intrasubstance tears showing increased signal intensity, longitudinal tears, and complete tendon tears.26

Treatment

Conservative Management

Initially, conservative management is indicated, with rest combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immobilization using a plaster cast or tape, or orthotic shoe modifications. There is no consensus about whether to use corticosteroid injections, and cases of tendon rupture after corticosteroid injections have been described.28

Surgery is indicated if conservative management for 3 to 6 months does not resolve the complaints.29 It can be performed by an open or endoscopic procedure. An open synovectomy is performed by sharp dissection of the inflamed synovium while preserving the blood supply to the tendon. Postoperative management consists of plaster cast immobilization for 3 weeks, with the possible disadvantage of formation of new adhesions, followed by wearing a functional brace with controlled ankle movement for another 3 weeks and physical therapy.

Endoscopic synovectomy is indicated when access allows radical removal of inflamed synovium.30 Several published studies have described successful endoscopic synovectomy and the advantages related to minimally invasive surgery.9,31,32

Surgical Technique

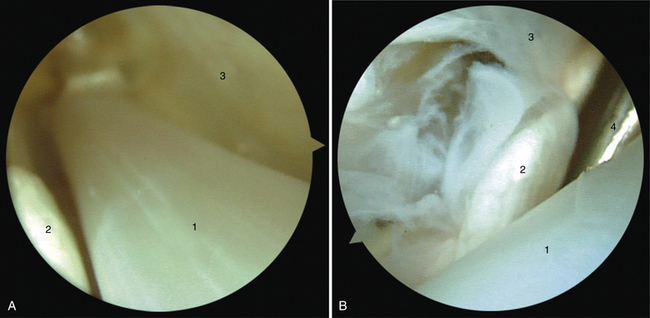

We prefer to make the two main portals directly over the tendon: 2 to 3 cm distal and 2 to 3 cm proximal to the posterior edge of the medial malleolus (Fig. 16-5). The distal portal is made first; the incision is made through the skin, and the tendon sheath is penetrated by the arthroscopic shaft with a blunt trocar. A 2.7-mm, 30-degree arthroscope is introduced, and the tendon sheath is filled with saline. Irrigation is performed using gravity flow.

When remaining in the posterior tibial tendon sheath, the neurovascular bundle is not in danger. When a rupture of the posterior tibial tendon is seen, endoscopic synovectomy is performed (Fig. 16-6),and the rupture is repaired through a mini-open approach. Magnifying the tendon endoscopically enhances localization and extent of the rupture, and it minimizes the incision required for repair. At the end of the procedure, the portals are sutured to prevent sinus formation.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

ENDOSCOPIC FLEXOR HALLUCIS LONGUS RELEASE

FHL tenosynovitis is a well-recognized cause of posteromedial ankle pain. In ballet dancers, this entity has been described as dancer’s tendinitis.33 Athletes performing repetitive forceful push-offs are at risk for developing FHL tendinitis.34

FHL tendinitis and posterior ankle impingement based on the os trigonum syndrome are distinct entities, but they frequently coexist because of their close anatomic orientation.5,35,36 If conservative management fails, surgical intervention involves removal of the os trigonum, tendon débridement, and a release of the flexor retinaculum and tendon sheath at the level of the posterior talar process. In 2000, van Dijk introduced a two-portal endoscopic hindfoot approach that provided excellent access to the posterior aspect of the ankle and subtalar joint.37,38 Extra-articular structures of the hindfoot, such as the os trigonum and FHL tendon, can be assessed.38 This minimally invasive technique has been anatomically and clinically demonstrated to be safe and reliable, and it compares favorably with open surgery in terms of less morbidity and a quicker recovery.39–42

Anatomy

The FHL is the most laterally located bipennate muscle of the human calf. At the level of the ankle and subtalar joint complex, the FHL tendon runs distally in a fibro-osseous gliding channel located between the posteromedial and lateral talar processes. At this level, the tendon is kept in place by the flexor retinaculum. The FHL tendon passes distally and medially underneath the sustentaculum tali to eventually insert in the distal phalanx of the hallux.43

Isolated FHL tendon pathology is almost exclusively located behind the medial malleolus at the level of the fibro-osseous tunnel.10,35,36,44 Hypertrophy, a nodule, or a low-riding muscle belly can cause the musculotendinous junction to be pulled inside the narrow tunnel, producing stenosing tenosynovitis, also referred to as triggering of the great toe or hallux saltans.45 Maximal tendon tension (i.e., hyper-dorsiflexion of the ankle and great toe) can cause tendinopathy of the FHL. Tendon degeneration and ruptures most frequently occur in the region of this fibro-osseous tunnel. This can be explained by the relative incongruity between the FHL and its tunnel in a fully plantar-flexed or dorsiflexed position.35 Another hypothesis is an avascular zone at this level of the tendon, as described by Petersen and colleagues.46

Posterior ankle impingement, caused by a soft tissue or bony impediment, is frequently associated with FHL tenosynovitis at the level of the fibro-osseous tunnel. Displacement of an os trigonum, a Cedell fracture, and a hypertrophic posterior talar process are examples of posterior bony ankle impingement that can cause associated tenosynovitis. Scar tissue around the tendon can provide local irritation. Posteromedially located talar osteochondral defects have been mentioned as a cause of FHL tendinopathy.47 During the stance phase of walking, the ankle joint is in dorsiflexion, and the talar dome is in closest contact with the FHL tendon. In the push-off phase, the toes are actively flexed, moving the tendon in an opposite direction compared with the talar movement. The tendon shreds against the osteochondral defect and becomes irritated and inflamed.

Patient Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

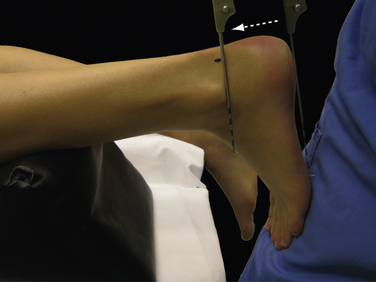

In patients with associated posterolateral ankle pain, a posterior impingement syndrome must be ruled out by means of a hyper-plantar flexion test (Fig. 16-7). The forced passive hyper-plantar flexion test result is positive when the patient experiences recognizable posterior ankle pain. A negative test result rules out a posterior ankle impingement syndrome. A positive test result is followed by a diagnostic infiltration of lidocaine in the posterior ankle compartment. Disappearance of pain after infiltration confirms the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Imaging

After performing a thorough history and physical examination, the diagnosis can be confirmed or rejected by the use of available imaging techniques. If the history and physical examination do not reveal abnormalities, additional diagnostics can be used to search for or to rule out pathology (i.e., for medicolegal reasons). Close consultation between the orthopedic surgeon and the radiologist is necessary to decide on optimal radiographic diagnostics.48

In patients without a history of trauma but with isolated, recognizable posteromedial ankle pain during flexion of the great toe while palpating the tendon at the level of the gliding channel, no additional diagnostic tests are needed. If conservative treatment options fail, intervention demands a release regardless of the pathology. MRI can be valuable to rule out tendon ruptures.

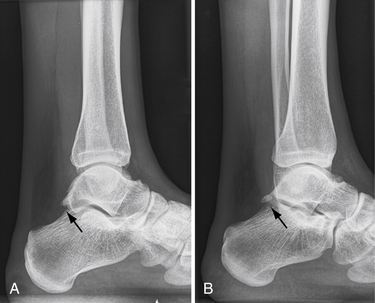

For patients with posteromedial ankle pain associated with a positive hyper-planter flexion test result, standard weight-bearing radiographs must be obtained with anteroposterior and lateral views. If differentiation of hypertrophy of the posterior talar process from an os trigonum is difficult, a lateral hindfoot radiograph with the foot in 25 degrees of exorotation in relation to the standard lateral ankle is advised (Fig. 16-8).49 For ballet dancers, a lateral radiograph with the foot in maximal plantar flexion can be useful to determine whether a bony posterior ankle impingement is present. In post-traumatic cases, spiral computed tomography (CT) can help to ascertain the extent of the injury or location of the osteochondral defect and the exact location of calcifications or fragments.

Treatment

Conservative Management

Nonoperative treatment options include rest, activity modification, ice therapy, NSAIDs, and physical therapy, such as stretching exercises.35,36 Infiltration of a corticosteroid around the tendon at the level of the tunnel can be performed as a next step. Avoid iatrogenic neurovascular bundle and tendon lesions.

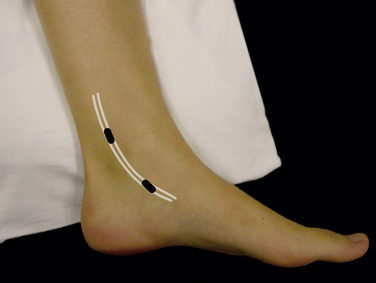

Posterior Ankle Arthroscopy

The procedure is carried out as outpatient surgery under general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia. The patient is placed in a prone position. The involved leg is marked with an arrow to avoid surgery on the wrong side. A tourniquet is inflated around the thigh for hemostasis. A small support is placed under the lower leg, making it possible to move the ankle freely (Fig. 16-9). We use a soft tissue distraction device when indicated.50

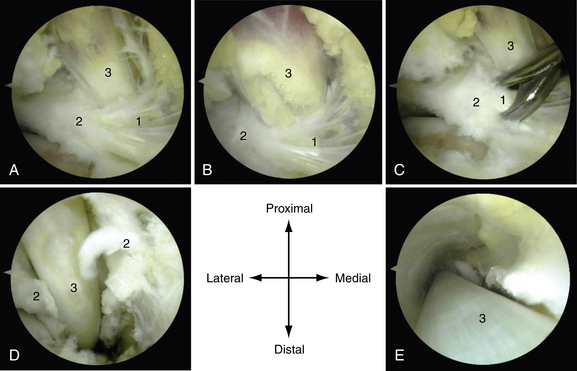

The posterolateral portal is made just above the line from the tip of the lateral malleolus and 1 cm anterior to the Achilles tendon (Fig. 16-10). After making a vertical stab incision, the subcutaneous layer is split by a mosquito clamp. The mosquito clamp is directed anteriorly, pointing toward the interdigital web space between the first and second toes. When the tip of the clamp touches the bone, it is exchanged for a 4.5-mm arthroscopic shaft, with the blunt trocar pointing in the same direction. By palpating the bone in the sagittal plane, the level of the ankle joint and subtalar joint can often be distinguished, because the prominent posterior talar process or os trigonum can be felt as a posterior prominence in between the two joints. The trocar is situated extra-articularly at the level of the ankle joint. The trocar is exchanged for the 4-mm arthroscope with the direction of view 30 degrees to the lateral side.

The posteromedial portal is made at the same level, just above the line of the tip of the lateral malleolus but just anterior to the medial aspect of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 16-11). After making a vertical stab incision, a mosquito clamp is introduced and directed toward the arthroscope shaft in a 90-degree angle. When the mosquito clamp touches the shaft of the arthroscope, the shaft is used as a guide to “travel” anteriorly in the direction of the ankle joint, all the way down while contacting the arthroscope shaft until it reaches the bone. The arthroscope is pulled slightly backward, sliding over the mosquito clamp until the tip of the mosquito clamp comes into view. The clamp is used to spread the extra-articular soft tissue in front of the tip of the lens. When scar tissue or adhesions are present, the mosquito clamp is exchanged for a 5-mm bone-cutter shaver. The tip of the shaver is directed in a lateral and slightly plantar direction toward the lateral aspect of the subtalar joint.

In the case of isolated tendinitis of the FHL tendon, the flexor retinaculum can be released by detaching it from the posterior talar process or os trigonum with an arthroscopic punch. Subsequently, the tendon sheath can be opened distally up to the level of the sustentaculum tali. The tendon sheath can be entered with the scope, allowing accurate tendon inspection and, if necessary, a further release can be performed (Fig. 16-12). Partial-thickness longitudinal tears are débrided. The proximal part of the tendon and the distal part of the muscle belly are inspected and débrided if inflamed, thickened, or if nodules are present. Adhesions and excessive scar tissue are removed.

By applying manual distraction to the calcaneus, the posterior compartment of the ankle opens up, and instruments can be introduced. We prefer to apply a soft tissue distractor at this point.50 When indicated, a synovectomy or capsulectomy, or both, can be performed. The talar dome can be inspected over almost its entire surface along with the complete tibial plafond. Osteochondral defects can be débrided, and drilling or microfracture can be performed.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol

The patient can be discharged the same day of surgery, and weight bearing is allowed as tolerated. The patient is instructed to elevate the foot when not walking to prevent edema. The dressing is removed 3 days postoperatively, after which the patient is permitted to shower. Performing active range-of-motion exercises for at least three times each day for 10 minutes each is encouraged. Patients with limited range of motion are directed to a physiotherapist.

1. Arthroscopy Association of North America. Master courses foot/ankle Available at http://www.aana.org/cme/MastersCourses/descriptions.aspx#Foot/Ankle accessed November 2009

2. Amsterdam Foot & Ankle Platform Available at http://www.ankleplatform.com/page.php?id=854 accessed November 2009

3. Bassett FHIII, Speer KP. Longitudinal rupture of the peroneal tendons. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:354-357.

4. Dombek MF, Lamm BM, Saltrick K, et al. Peroneal tendon tears. a retrospective review, J Foot Ankle Surg. 422003 250-258.

5. van Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle pain. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:545-554.

6. Selmani E, Gjata V, Gjika E. Current concepts review. peroneal tendon disorders, Foot Ankle Int. 272006 221-228.

7. Scholten PE, van Dijk CN. Tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:415-420. vii

8. Sobel M, Geppert MJ, Hannafin JA, et al. Microvascular anatomy of the peroneal tendons. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:469-472.

9. van Dijk CN, Kort N. Tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:471-478.

10. Benjamin M, Qin S, Ralphs JR. Fibrocartilage associated with human tendons and their pulleys. J Anat. 1995;187(Pt 3):625-633.

11. Kumai T, Benjamin M. The histological structure of the malleolar groove of the fibula in man. its direct bearing on the displacement of peroneal tendons and their surgical repair, J Anat. 2032003 257-262.

12. Monteggi GB. Instituzini Chirurgiche. Part III. Milan, Italy: xxxx; 1803. 336-341

13. Edwards ME. The relations of the peroneal tendons to the fibula, calcaneus and cuboideum. Am J Anat. 1928;42:213-253.

14. Eckert WR, Davis EAJr. Acute rupture of the peroneal retinaculum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:670-672.

15. Molloy R, Tisdel C. Failed treatment of peroneal tendon injuries. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:115-129. ix

16. Heckman DS, Reddy S, Pedowitz D, et al. Operative treatment for peroneal tendon disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:404-418.

17. Safran MR, O’Malley DJr, Fu FH. Peroneal tendon subluxation in athletes. new exam technique, case reports, and review, Med Sci Sports Exerc. 311999 S487-S492.

18. Rosenberg ZS, Bencardino J, Astion D, et al. MRI features of chronic injuries of the superior peroneal retinaculum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1551-1557.

19. Rockett MS, Waitches G, Sudakoff G, Brage M. Use of ultrasonography versus magnetic resonance imaging for tendon abnormalities around the ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:604-612.

20. de Leeuw PAJ, Golano P, van Dijk CN. A 3-portal endoscopic groove deepening technique for recurrent peroneal tendon dislocation. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;7:250-256.

21. Myerson MS. Adult acquired flatfoot deformity. treatment of dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon, Instr Course Lect. 461997 393-405.

22. Michelson J, Easley M, Wigley FM, Hellmann D. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:156-161.

23. Trnka HJ. Dysfunction of the tendon of tibialis posterior. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:939-946.

24. Frey C, Shereff M, Greenidge N. Vascularity of the posterior tibial tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:884-888.

25. Bulstra GH, Olsthoorn PG, Niek van DC. Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:421-427. viii

26. Kong A, Van d, V. Imaging of tibialis posterior dysfunction. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:826-836.

27. Miller SD, Van HM, Boruta PM, et al. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of posterior tibial tendon pathology. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:555-558.

28. Porter DA, Baxter DE, Clanton TO, Klootwyk TE. Posterior tibial tendon tears in young competitive athletes. two case reports, Foot Ankle Int. 191998 627-630.

29. Lui TH. Endoscopic assisted posterior tibial tendon reconstruction for stage 2 posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1228-1234.

30. Paus AC. Arthroscopic synovectomy. When, which diseases and which joints. Z Rheumatol. 1996;55:394-400.

31. van Dijk CN, Kort N, Scholten PE. Tendoscopy of the posterior tibial tendon. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:692-698.

32. van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Kort N. Tendoscopy (tendon sheath endoscopy) for overuse tendon injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1997;5:170-178.

33. Hamilton WG. Tendonitis about the ankle joint in classical ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 1977;5:84-88.

34. Leach RE, DiIorio E, Harney RA. Pathologic hindfoot conditions in the athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:116-121.

35. Hamilton WG, Geppert MJ, Thompson FM. Pain in the posterior aspect of the ankle in dancers. Differential diagnosis and operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1491-1500.

36. Sammarco GJ, Cooper PS. Flexor hallucis longus tendon injury in dancers and nondancers. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:356-362.

37. van Dijk CN, van Bergen CJA. Advancements in ankle arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:635-646.

38. van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Krips R. A 2-portal endoscopic approach for diagnosis and treatment of posterior ankle pathology. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:871-876.

39. Lijoi F, Lughi M, Baccarani G. Posterior arthroscopic approach to the ankle. an anatomic study, Arthroscopy. 192003 62-67.

40. Scholten PE, Sierevelt IN, van Dijk CN. Hindfoot endoscopy for posterior ankle impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2665-2672.

41. Sitler DF, Amendola A, Bailey CS, et al. Posterior ankle arthroscopy. an anatomic study, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 84A2002 763-769.

42. Willits K, Sonneveld H, Amendola A, et al. Outcome of posterior ankle arthroscopy for hindfoot impingement. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:196-202.

43. Sarrafian SK. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle. Descriptive, Topographic, Functional. 1983 JB Lippincott Philadelphia, PA

44. Solomon R, Brown T, Gerbino PG, Micheli LJ. The young dancer. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:717-739.

45. McCarroll JR, Ritter MA, Becker TE. Triggering of the great toe. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:184-185.

46. Petersen W, Pufe T, Zantop T, Paulsen F. Blood supply of the flexor hallucis longus tendon with regard to dancer’s tendinitis. injection and immunohistochemical studies of cadaver tendons, Foot Ankle Int. 242003 591-596.

47. van Dijk CN, de Leeuw PAJ, Krips R. Diagnostic and operative ankle and subtalar joint arthroscopy. In: Porter DA, Schon LC, editors. Baxter’s The Foot and Ankle in Sport. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:355-382.

48. van Dijk CN, de Leeuw PA. Imaging from an orthopaedic point of view. What the orthopaedic surgeon expects from the radiologist? Eur J Radiol. 2007;62:2-5.

49. van Noek DC. Anterior and posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:663-683.

50. van Dÿk CN, Verhagen RA, Tol HJ. Technical note. resterilizable noninvasive ankle distraction device, Arthroscopy. 172001 E12.