Techniques of mastectomy

tips and pitfalls

General considerations

The patient may have risk factors for poor wound healing, which include:

Smoking

There are more than 4000 chemicals present in cigarette smoke, including nicotine and carbon monoxide.1 One effect of nicotine is to cause vasoconstriction of the dermal–subcutaneous vascular plexus. This has important consequences, as mastectomy flaps rely on this plexus for survival.2 As well as inducing a hypoxic state and causing vasoconstriction, smoking can lead to increased platelet aggregation, which results in the formation of tiny thromboses in capillaries. This is detrimental to wound healing, which relies heavily on blood flow in newly formed capillaries. Smokers have higher levels of fibrinogen and haemoglobin, which increase blood viscosity, which further increases the likelihood of blood clotting, and blood velocity can be reduced by up to 42% in smokers.3 The combination of decreased oxygen delivery to tissues and the thrombogenic effects of smoking, together with increased viscosity and reduced velocity, explain why wound healing in smokers is significantly impaired.

The link between smoking and wound healing was first documented in the 1970s. One study of 425 patients undergoing mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery identified smoking as an independent predictor for wound infection and skin necrosis regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked.4

Another study of 716 patients having free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flaps showed mastectomy flap necrosis, abdominal flap necrosis and abdominal hernias were significantly higher in smokers.5 This study did demonstrate a dose effect with smokers who had a history of more than a pack a day for 10 years being at increased risk of developing problems compared with smokers who had smoked for a smaller number of pack years (55.8% vs. 23.8%). One observation in this study was that delayed breast reconstruction in smokers was associated with a significantly lower rate of wound complications compared with immediate breast reconstruction in smokers. The risk of wound complications in delayed reconstructions in smokers was similar to the rate in non-smokers. Complications were also less common in women who stopped smoking 4 or more weeks before surgery.

There was one small study of 108 patients investigating smoking cessation prior to surgery that was a randomised clinical trial with 40 patients in the control group and 68 patients in the interventional group.6 Patients assigned to intervention were given counselling and nicotine replacement therapy. This study showed a significant reduction in complications in the intervention group, with a reduction in both wound-related complications and the need for secondary surgery.

Considerations for simple mastectomy

In addition to general considerations, four questions should be answered:

The all too frequently seen but completely avoidable complication of mastectomy is redundant tissue, also known as a dog ear, which is unsightly, causes difficulty with bra fitting and often chafes on the prosthesis, arm or bra (Fig. 5.1).

This is a simple and very effective option to enable women with a heavy breast to wear a lighter prosthesis and feel less unbalanced (Fig. 5.2a). In some cases a woman may choose a bilateral mastectomy to achieve better overall symmetry.

Figure 5.2 (a) A low mastectomy scar with contralateral reduction. (b) Delayed reconstruction with LD flap.

The scar should be sympathetic to the method of delayed reconstruction planned. In most cases a low scar is best (as in Fig. 5.2a). It allows a flap-based reconstruction to be set at the inframammary fold, with the upper scar low enough to be hidden in low- neckline clothes (Fig. 5.2b).

Planning a mastectomy

• Examine the patient sitting up to assess lateral tissue and plan the likely lateral end of scar. The predicted lateral extent of the incision can be marked.

• The extent of the scar is important if radiotherapy is planned as the whole scar will be covered and can result in large volumes of tissue being treated if the scar extends a long distance posteriorly.

• Mark any skin that needs to be removed over the cancer.

• Decide if a second incision is required for sentinel node biopsy (usually not necessary).

Technique

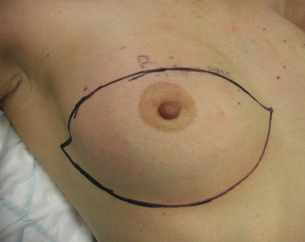

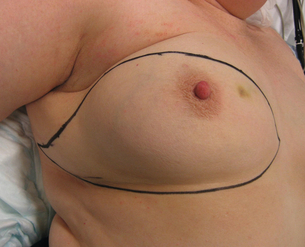

Most scars can be based around the inframammary fold (IMF). The incision pattern is drawn in theatre initially with a line at or just below the IMF (in women with any intertrigo the scar should be placed below this). Then with repeated upward and downward movement of the breast the planned transposition of this line on the breast skin can be marked (Fig. 5.3). In most cases the upper incision line passes a little above the areola. Attention should be paid to the degree of tension applied to the upward or downward breast movement as this represents the tension that will be exerted on the wound on closure. The upper and lower incision lines should be planned so that they meet comfortably but without excess laxity. Incisions should be planned to avoid any dog ear. To achieve this it is often best to continue the incision along the bra line laterally, curving up slightly until the upper and lower lines meet (Fig. 5.4) or, if there is doubt about how to fashion the lateral end, stop the incision at the lateral edge of the breast and fashion it once the mastectomy is complete, before closure (see comments regarding dog ear below). Transverse mastectomy scars are commonly used but rarely, if ever, can be closed without significant excess of tissue, particularly laterally. It is beholden on all surgeons to be familiar with a range of mastectomy incisions and given that there are always better alternatives, transverse mastectomy scars should be avoided.

Inferior broad-based flaps can be designed to allow skin excisions in the upper pole. In breasts with a high nipple position or in cases where skin excision in the upper pole is desired, the lower incision line can be adjusted to preserve skin on the lower flap. Such modifications to the inferior skin flap should be broad based. Other scar patterns to consider in such situations include the Wise pattern or dome-shaped scar (Fig. 5.5).

Lighting: A headlight is valuable and should be part of the equipment available for any breast operation.

Retraction: Care should be taken with the edges of the mastectomy flaps. Sharp hooks or tissue forceps applied to dermis cause less trauma to mastectomy flaps than blunt retractors.

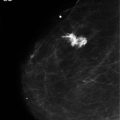

Identifying the ‘plane’: Some would contest its existence, but there is a readily identifiable plane between the breast and subcutaneous fat that defines the dissection. That is not to say that it is obvious in every case and it may be quite irregular. The thickness of fat on mastectomy flaps varies between patients and increases further the distance from the nipple. Importantly, however, the subcutaneous vessels (extensions of the intercostal perforators) lie superficial to this plane. The plane can be defined by hydrodissection infiltrating saline (I use 1 in 1 million – others use 1 in 500 000)/adrenaline using a spinal needle, Verres needle or blunt infiltration cannula attached to a 50-mL syringe or a pressure bag (100–150 mmHg) of saline/adrenaline solution. The plane is identified as a white line after performing a skin incision before the flaps are lifted and retracted. With opposing retraction on skin and breast and light initial dissection, tissues are seen to separate at the level of the plane. Dissection then chases this white line with continued opposing retraction (with skin hook retraction on the upper flap, skin kept as straight as possible), cutting on its superficial surface. This produces a flap of uniform thickness that will be thicker in fatter women and thinner in others.

Surgical tools: My preference is to use a hand-held diathermy on a fulgurate setting throughout. If using hydrodissection, scissors or a knife can be used as the plane is bloodless. Different surgeons have different preferences. Blood loss should be less than 100 mL if diathermy is used. Some prefer scissors or the knife because of concern of the ‘burn’ that results from diathermy dissection; blood loss is generally greater with scissors or the knife.

Preserving the intercostal perforators: These represent the main blood supply to the mastectomy flaps once the breast tissue is removed. Their preservation is important, not just for the prevention of flap necrosis and wound problems, but also to maximise the longer-term quality of the skin. The largest tend to originate at the second or third intercostal space. These are usually encountered early in the dissection just superior to the areola and can be seen (especially in thin women) and preserved during dissection upwards and medially.

Issues regarding posterior margin: Strong opinions are often expressed regarding whether or not to excise the pectoral fascia and when to excise some muscle. The posterior plane or breast plate is very well defined, certainly in the middle and upper part of the breast. In these areas there is no need and no clinical evidence to support removal of the pectoral fascia. For mastectomy, preservation of the fascia is only an issue if the cancer lies posterior in the breast. If this is the case and there is any doubt about adherence to muscle, then a portion of pectoral muscle can also be taken. In such situations a wide margin of muscle excision avoids the situation where a margin is reported as histologically involved or close (often due to its contraction following fixation), at no additional cost in terms of morbidity.

Inframammary fold: With a simple mastectomy this is normally excised, avoiding a ridge and producing a flat surface.

The anterior fat over the shoulder: This is often prominent and yet not part of the breast. If not contoured, it can produce a bulge in the upper outer aspect of the mastectomy site. Undermining the upper flap towards the shoulder often releases this fat pad so that it is more evenly distributed.

A flat surface: After mastectomy, before closure, the chest wall should be palpated with the flat of the hand to make sure there are no ridges or prominent irregularities. If so, these can be contoured prior to closure. There is some evidence that suturing the mastectomy flaps to the chest wall, so-called ‘quilting’, reduces seroma formation.

Suturing: Interrupted deep dermal sutures to approximate skin edges and gather any discrepancy between upper and lower flaps are advisable prior to a subcuticular suture. My preference is to use 3/0 absorbable suture throughout.

Managing the potential dog ear: Several techniques have been described for this. First and foremost, however, do not use incisions – such as a transverse mastectomy scar – which produces a ‘dog ear’ or ‘angel wings’ in the majority of patients in whom it is used. One approach to reduce ‘dog ears’ is as follows. If the patient is fairly thin, a flat lateral chest wall can be achieved by using an IMF scar as described above. In women with excess lateral tissue, it is often useful to complete the mastectomy with minimal extension of the scar laterally and then tidy this part of the scar. The easiest way to do this is to close the skin with temporary placement of skin staples. This then allows variations of lateral scar closure to be visualised before commitment to any particular one. The staples can be removed and replaced as many times as necessary to get the best and shortest scar. Final wound closure is with two layers of absorbable deep and superficial subcuticular absorbable sutures. Some lateral laxity can be accommodated by gathering the upper flap.

The three most useful techniques for lateral scar design in my experience are lateral extensions of the IMF scar, liposuction and the fishtail technique (Fig. 5.6). When performing fishtailing use staples to approximate the wound edges and take the lateral end of the transverse incision and move it and staple it medially to flatten out the lateral end of the wound to leave two smaller dog ears. Mark out incisions to excise these dog ears and then excise or de-epithelialise these (to preserve blood supply at the ‘T’ where the three wounds meet) to produce the fishtail pattern. Ensure that the wound is flat, if necessary by using liposuction. Liposuction is a useful adjunctive technique in many mastectomies.

Goldilocks mastectomy

Although it has been tradition to excise the excess skin over the breast during a mastectomy to leave a flat chest wall, other options may be considered. Skin that would normally be discarded may be de-epithelialised, shaped and buried to improve the cosmetic result. This may avoid the concave appearance that often results from mastectomy and in some cases can produce a small breast mound. Skin incisions are marked as normal but the skin between the upper and lower incisions is de- epithelialised. The de-epithelialised lower flap is then buried under the upper mastectomy flap. The amount of tissue that can be preserved and used in this way will vary considerably, depending on risk factors for tissue viability and the amount of skin required to be removed for oncological reasons. Care is required in wound closure to maintain the superficial vasculature (Fig. 5.7a–c).

Considerations for mastectomy with immediate reconstruction

Of the general issues listed above, smoking is a particular concern and the major risk factor for flap necrosis and wound problems with skin-sparing mastectomy.7 The following questions should be considered:

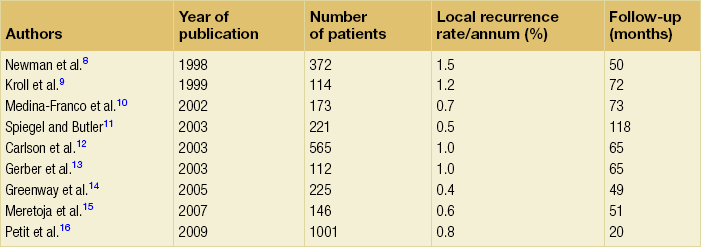

In general terms, the same principles apply as described above. However, immediate breast reconstruction is enhanced by preserving most (if not all) of the breast skin. Studies assessing the safety of this procedure relative to rates of local recurrence are summarised in Table 5.1. Although there are several that report acceptable recurrence rates, no large randomised trial data are available. It seems sensible to apply the same principles as one would for simple mastectomy. In other words, if the cancer is close to skin such that a healthy margin of normal tissue cannot easily be excised around it, then the overlying skin should be resected. An important principle of oncoplastic surgery is that treatment must not be compromised for the sake of cosmesis. Different designs of skin-sparing mastectomy can allow skin excisions at any site.

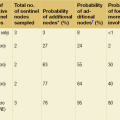

Table 5.1

Case series of over 100 patients reporting local recurrence rates after skin-sparing mastectomy

This is increasingly considered an option in small breasts, particularly for prophylactic mastectomy but also in cancer cases.8–16 Scar placement in this setting should allow good access to the breast and the nipple itself.

Planning a mastectomy with reconstruction

Tissue-based reconstruction

Circumareolar: This is perhaps the most commonly employed technique. It gives excellent access to all but very large breasts. It can be extended easily by a lateral or inferior extension or by widening the circular skin excision. The resulting defect is replaced with skin from the flap, often with nipple reconstruction at the same time (Fig. 5.8).

Wise pattern: This is another commonly employed technique that can be used for any ptotic breast. The design is more conservative than would be used for a standard breast reduction, and is often best planned as very conservative, with adjustment of the vertical limbs at the time of closure according to viability and tension. A vulnerable part of this design is the lateral part of the inverted ‘T’. A recent modification is to de-epithelialise the lower mastectomy flap as for a ‘Goldilocks’ mastectomy so the vulnerable part of the T incision is placed directly over the de-epithelialised lower flap of the mastectomy scar. With division of the lateral thoracic vessels as part of the mastectomy, this often ends up as the most ischaemic part of the mastectomy flap. Designing an inverted ‘V’ component to the lower incision that will release tension at the ‘T’ junction is often prudent (Fig. 5.9). Preservation of a larger section of lower flap skin until the time of closure enables the option of wider skin excision if viability is a concern or, as outlined above, de- epithelialisation and double-breasting of the scar.

Implant reconstruction

Wise pattern: This is probably the best option for the large breast and possibly any breast with some ptosis. It gives excellent access to the breast. It is particularly useful when a lower de-epithelialised flap is being used to create a partial submuscular/partial subdermal pocket (Fig. 5.10a,b). This has become a standard approach when available. A de-epithelialised lower flap can also be combined with the use of a dermal matrix for breast reconstruction and can provide complete cover of the dermal matrix, particularly in the vulnerable area where all three scars meet.

Vertical: This is a good option in small breasts when a total submuscular pocket is planned. Shortening of the scar is rarely possible to any significant degree. This can sometimes be combined with a de-epithelialised vertical mastopexy scar to allow repositioning of the nipple/areola.

Is a second incision required for sentinel lymph node biopsy?

Undesirable scar patterns

• Hemicircumareoalar. This allows very restricted and, in my opinion, difficult access to the breast in all but very small breasts and compromises nipple blood supply.

• Any long transverse/oblique scar. These really have no role in immediate reconstruction.

• Purse-string. This is intuitive, but creates ischaemia at the skin edge, can result in a central sinus, stretches to produce an unsightly scar, and results in a scar that presents difficulties for nipple reconstruction and tattooing.

Technique

Preoperative marking: Mark with the patient standing. Put a mark on the midline and draw a dashed line around the circumference of the breast. For the periphery above the IMF take the weight of the breast and move it towards each periphery to enable the edge of the breast to be seen and marked. In practice this becomes most useful when a mastectomy is performed with the patient on their side simultaneous to raising a latissimus dorsi (LD) flap. Other markings will depend on the scar pattern to be used.

For Wise and vertical patterns the breast meridian is drawn and patients marked up as for a reduction or mastopexy but with more conservative vertical incision lines (Fig. 5.10a). In Wise pattern mastectomy the vertical components are usually 10 cm in length from apex to horizontal incision. They often hug the areola margin. They can always be trimmed if necessary on closure and the ‘T’ junction modified as described above.

Pectoral fascia: It is an advantage to preserve this if an implant reconstruction is being performed as it adds reinforcement to a submuscular pocket.

Wound closure: The use of deep dermal interrupted sutures before subcuticular closure maximises wound quality. Wound edges should be ‘freshened’, particularly if traumatised by retraction during operation. Often wounds can be double-breasted, with the small reinforcing de-epithelialised segment.

Skin stapler: This is particularly useful in Wise pattern mastectomy or any mastectomy where a skin-bearing flap is being inserted. The shape can be visualised and flaps trimmed as appropriate. Staples are always removed and wound closure should be with absorbable subcuticular sutures.

Over-dressing: If a support over-dressing (e.g. gauze and Elastoplast) is used this should be lightly applied so as not to compromise mastectomy flap blood flow. Steri-strips, if used, should be wide 0.5- or 1-inch and placed parallel to the wound, not at 90° to the skin incision, as they can cause blistering.

Flap necrosis

Using the principles and techniques described this should be a rarity (1% or 2% of cases). The main reasons for it are smoking, poor technique selection, poor execution of dissection, failure to preserve the intercostal perforators and too much tension of wound edges. In the circumstances where flap necrosis is encountered, early surgical debridement may allow direct re-closure and usually results in a satisfactory outcome (Fig. 5.12a,b). Occasionally a small skin graft is required.

Radical mastectomy

• lateral chest wall perforator flap;

• deep inferior epigastric perforator/transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap.

All have a potential role depending on the size of defect, patient fitness and suitability of donor sites.

References

1. Krueger, J.K., Rohrich, R.J., Clearing the smoke: the scientific rationale for tobacco abstention with plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(4):1063–1073. 11547174

2. Chang, L.D., Buncke, G., Slezak, S., et al, Cigarette smoking, plastic surgery and microsurgery. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1996;12(7):467–474. 8905547

3. Sarin, C.L., Austin, J.C., Nickel, W.O., Effects of smoking on digital blood flow velocity. JAMA. 1974;229(10):1327. 4277467

4. Sorensen, L.T., Horby, J., Friis, E., et al, Smoking as a risk factor for wound healing and infection in breast cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28(8):815–820. 12477471

5. Chang, D.W., Reece, G.P., Wang, B., et al, Effect of smoking on complications in patients undergoing free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2374–2380. 10845289

6. Moller, W.M., Villebro, N., Pederson, T., et al, Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9301):114–117. 11809253

7. Woerdeman, L.A.E., Hage, J.J., Hofland, M.M.I., et al, A prospective assessment of surgical risk factors in 400 cases of skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction with implants to establish selection criteria. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 119:455–463. 17230076

8. Newman, L.A., Kuerer, H.M., Hunt, K.K., et al, Presentation, treatment, and outcome of local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 1998; 5:620–626. 9831111

9. Kroll, S.S., Khoo, A., Singletary, S.E., et al, Local recurrence risk after skin-sparing and conventional mastectomy: a 6-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999; 104:421–425. 10654685

10. Medina-Franco, H., Vasconez, L.O., Fix, R.J., et al, Factors associated with local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction for invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg 2002; 235:814–819. 12035037

11. Spiegel, A.J., Butler, C.E., Recurrence following treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ with skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 111:706–711. 12560691

12. Carlson, G.W., Styblo, T.M., Lyles, R.H., et al, Local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy: tumor biology or surgical conservatism? Ann Surg Oncol 2003; 10:108–112. 12620903

13. Gerber, B., Krause, A., Reimer, T., et al, Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple–areola complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg 2003; 238:120–127. 12832974

14. Greenway, R.M., Schlossberg, L., Dooley, W.C. Fifteen-year series of skin-sparing mastectomy for stage 0 to 2 breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2005; 190:918–922.

15. Meretoja, T.J., von Smitten, K.A.J., Leidenius, M.H.K., et al, Local recurrence of stage 1 and 2 breast cancer after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction in a 15 year series. Eur J Surg Oncol 2007; 33:1142–1145. 17490847

16. Petit, J.-Y., Veronesi, U., Orecchia, R., et al, Nipple sparing mastectomy with nipple areola intraoperative radiotherapy: one thousand and one cases of a five years experience at the European Institute of Oncology of Milan (EIO). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 117:333–338. 19152026