CHAPTER 66 Techniques and Complications of Bone Graft Harvesting

Anterior Ilium

Three methods of harvesting autogenous bone graft from the anterior iliac crest are commonly used, each yielding only limited amounts of bone. The first is trephine curettage,1 which is a method of harvesting bone graft from either the anterior or posterior ilium. It usually yields only small curettings of cancellous bone. A small incision is made over either the posterior superior iliac spine or the iliac tubercle. Along the iliac crest, the tubercle is 5 cm posterolateral to the anterior superior iliac spine. The periosteum over the iliac crest is incised, and a small portion of the outer and inner table muscles is stripped slightly over the edge of the iliac crest. A Leksell rongeur or small osteotome is used to make a small rectangular window in the iliac crest by removing the cortex. This allows access to the medullary cavity of the ilium, and curets are used to remove cancellous bone. Because the crest is much thinner anteriorly than posteriorly, the area beneath the iliac tubercle must be used for bone harvest because it is the thickest portion of the anterior iliac wing.

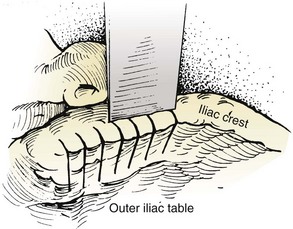

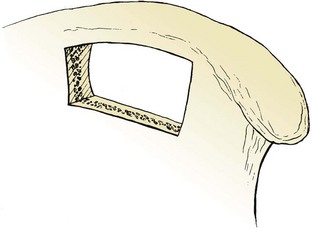

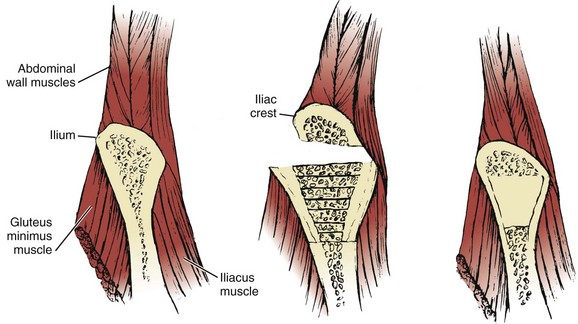

The trapdoor method (Fig. 66–1) of harvesting bone graft allows more extensive access to bone graft and is best suited for the anterior ilium. A skin incision is made over the anterior iliac crest, and an incision is made into the periosteum overlying the outer aspect of the crest. Beginning at the outer periosteal incision, a  -inch straight osteotome is used to make a horizontal cut in the iliac crest through both tables. The periosteum and fascial attachments of the iliacus and abdominal wall muscles (see Fig. 66–1) must remain intact on the inner edge of the horizontal cut to allow the crest to be “hinged back” like a trapdoor. Cancellous bone is then harvested from the medullary cavity, and the gluteal and abdominal wall fasciae are reapproximated after harvest. The normal contour of the iliac crest remains intact and yields cancellous strips and chips of bone.

-inch straight osteotome is used to make a horizontal cut in the iliac crest through both tables. The periosteum and fascial attachments of the iliacus and abdominal wall muscles (see Fig. 66–1) must remain intact on the inner edge of the horizontal cut to allow the crest to be “hinged back” like a trapdoor. Cancellous bone is then harvested from the medullary cavity, and the gluteal and abdominal wall fasciae are reapproximated after harvest. The normal contour of the iliac crest remains intact and yields cancellous strips and chips of bone.

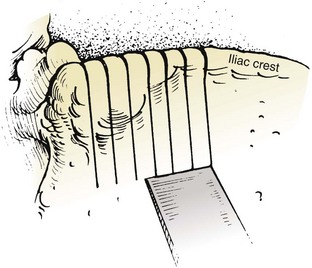

The subcrestal window technique (Fig. 66–2) is performed by making a skin incision over the anterior iliac crest near the iliac tubercle. The outer and inner table muscles are stripped subperiosteally from the ilium, and a small straight osteotome is used to remove the desired shape of bicortical ilium. This bone block can vary in size or shape, depending on that of the ilium itself. Care must be taken with the osteotome not to penetrate through the iliacus muscle medially (see Fig. 66–1).

FIGURE 66–2 The subcrestal window technique of harvesting bone grafts. The iliac crest is left completely intact.

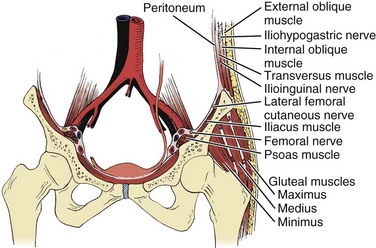

Full-thickness tricortical grafts, which include the iliac crest, may also be harvested from the anterior ilium. A skin incision is made just superior or inferior to the anterior iliac crest, and both the inner and outer table muscles must be subperiosteally stripped. Alternatively, if a retroperitoneal or thoracoabdominal approach to the lumbar spine has been performed, subcutaneous dissection over the iliac crest, superficial to the abdominal musculature, obviates the need for a separate skin incision. The periosteum is then incised overlying the anterior iliac crest, thus releasing the abdominal wall muscles from their insertion on the iliac crest itself (Fig. 66–3). Stripping of the outer (tensor fascia lata and gluteus medius) and inner (iliacus) table muscles can be accomplished (see Fig. 66–3), thereby exposing the entire thickness of the ilium for harvest. An oscillating saw or osteotome can then be used to remove full-thickness tricortical grafts.

Posterior Ilium

The ideal method of harvesting bone graft from the posterior ilium should yield sufficient quantity of cancellous and corticocancellous bone for posterior or posterolateral fusion. Methods such as “oblique sectioning of the crest,”2 “cortical subcrestal windows,” and “trapdoors” are usually performed anteriorly and provide only limited amounts and sizes of bone graft, which are usually insufficient for posterior lumbar arthrodesis. Gouges tend to provide uneven corticocancellous strips and chips of bone that may not be suitable to span adjacent transverse processes. Curets provide small chips of bone that are suitable only as “filler” pieces. Osteotomes work well by providing relatively consistent sizes and shapes of bone pieces that can properly bridge adjacent transverse processes. Ideally, the osteotome should yield pieces of bone at least 6 cm in length, 5 to 7 mm in width, and with a cancellous thickness of 5 to 7 mm.

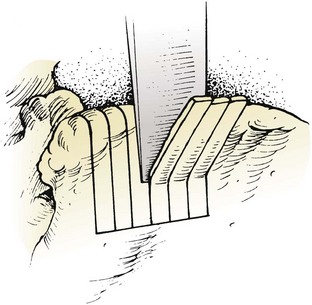

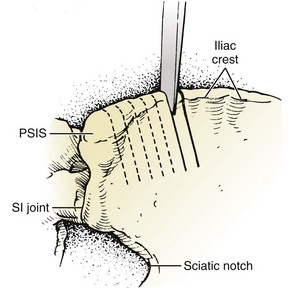

Bone graft harvest is begun by exposing the posterior iliac crest through a separate skin incision (Fig. 66–4). Alternatively, if the laminectomy skin incision allows, subcutaneous dissection may be performed through it, thereby permitting the surgeon to avoid a separate incision in the skin. The periosteum is incised over the iliac crest, and subperiosteal stripping of the outer table muscles of the posterior ilium is performed by using a Cobb periosteal elevator. A Taylor retractor is placed deep in the wound and oriented vertically to avoid penetrating the sciatic notch. A sterile gauze or chain is then hung from the handle of the retractor and a small weight (usually 2 to 5 pounds) is suspended from it, thereby leaving both of the surgeon’s hands free. A  -inch straight osteotome is used to cut parallel strips of bone from the crestal edge in a ventral direction (Fig. 66–5). Care is taken to prevent full-thickness (bicortical) bone cuts. Successive vertical cuts of equal length are made approximately 7 mm apart. A

-inch straight osteotome is used to cut parallel strips of bone from the crestal edge in a ventral direction (Fig. 66–5). Care is taken to prevent full-thickness (bicortical) bone cuts. Successive vertical cuts of equal length are made approximately 7 mm apart. A  -inch curved osteotome is then used to connect the cuts on top (Fig. 66–6) of the crest and distally (Fig. 66–7). The curved osteotome is then gently tapped ventrally between the inner and outer tables of the ilium to connect with the distal cut (Fig. 66–8). The corticocancellous strips are removed, leaving a majority of the cancellous bone of the intramedullary cavity available for removal with gouges, with residual cancellous bone then removed by the curets.

-inch curved osteotome is then used to connect the cuts on top (Fig. 66–6) of the crest and distally (Fig. 66–7). The curved osteotome is then gently tapped ventrally between the inner and outer tables of the ilium to connect with the distal cut (Fig. 66–8). The corticocancellous strips are removed, leaving a majority of the cancellous bone of the intramedullary cavity available for removal with gouges, with residual cancellous bone then removed by the curets.

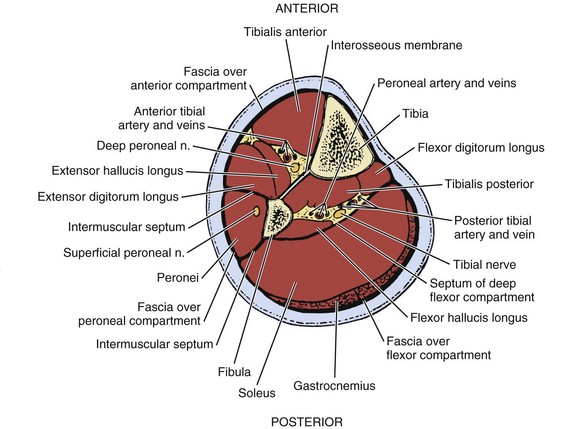

Fibula

With readily available allograft bone, autogenous fibula is rarely used. Its uses are generally limited to anterior structural support in the cervical spine after corpectomy. In order to minimize problems with ambulation, autogenous fibula must be harvested meticulously. Under tourniquet control, a skin incision is made to parallel to the posterior border of the fibula, centered at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the fibular shaft. The incision is carried down through the intermuscular septum onto the bone. Subperiosteal dissection is used to elevate the peroneal muscles from the anterolateral surface of the fibula, the extensor digitorum longus muscle from its anterior surface, the tibialis posterior muscle from its anteromedial surface, the flexor hallucis longus muscle from its posteromedial surface, and the soleus from the posterior surface (Fig. 66–9). It is essential to stay subperiosteal when circumferentially stripping the fibula, even though these muscles may not be individually recognizable. After the bone is completely stripped, a graft may be harvested with either an oscillating saw or a Gigli saw.

Rib

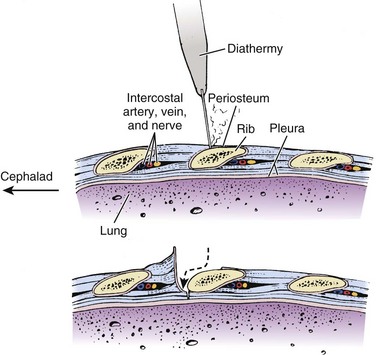

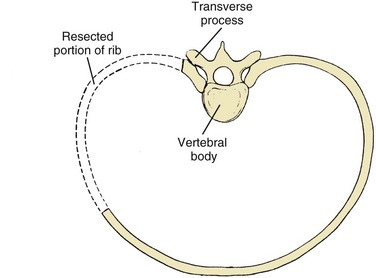

Ribs are harvested almost exclusively for use with thoracoabdominal or transthoracic approaches to the spine, where they are removed to assist exposure. Dissection through the latissimus dorsi and trapezius muscles exposes the rib and assists harvest. Electrocautery or a scalpel is used to incise the periosteum over the rib, and the superficial portion of the rib is subperiosteally stripped with a periosteal elevator (Fig. 66–10). A rib stripper is then used to completely subperiosteally strip the pleural surface of the rib. This maneuver is performed all the way to the vertebral and sternal ends of the ribs. A rib cutter is then used to excise the rib at its costochondral and costovertebral junctions (Fig. 66–11).

Complications of Bone Graft Harvest

Pain

Pain is considered a complication because it is the most common complaint after autogenous iliac bone graft harvest.3,4 Donor site pain may persist long after the arthrodesis site ceases to be a source of discomfort. Several studies5–7 have reported that up to 15% of patients may have persistent pain at the iliac donor site for more than 3 months after harvesting of the bone graft. There are no differences in the incidence and degree of pain between anterior and posterior harvest sites.8 Although it is opined that the pain is due to the extent of periosteal dissection, the rich blood supply and innervation of the site, and the role of weight bearing, none completely explains the persistent pain. However, limiting the degree of dissection and periosteal stripping will diminish the chance of this complication occurring.

Arterial Injury

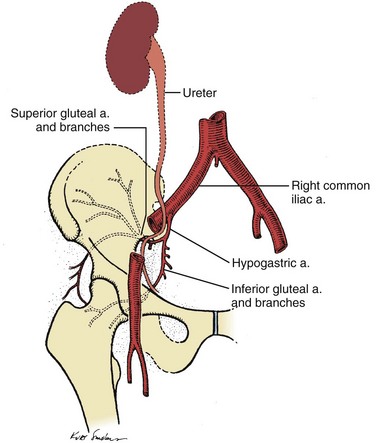

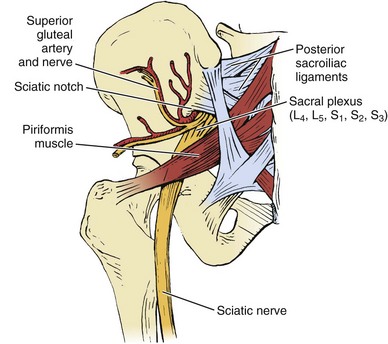

The superior gluteal artery arises from the internal iliac artery before it exits the pelvis. It then enters the gluteal region, through the proximal portion of the sciatic notch (Fig. 66–12), and supplies the bulk of the gluteal muscle. Formation of an arteriovenous fistula of the superior gluteal vessels has occurred from penetration of the sciatic notch with the sharp tip of a Taylor retractor used to provide exposure during bone harvest.9 I have encountered four cases of massive hemorrhage deep in the sciatic notch from inadvertent penetration of the notch by an osteotome or gouge during the harvesting of bone from the posterior ilium. In every case, the injured superior gluteal artery stump retracted proximally into the pelvis. In two of the four cases, exposure of the retracted injured vessel in the sciatic notch necessitated the use of a Kerrison rongeur to remove bone from the sciatic notch to gain successful control of bleeding. In one case, however, ligation of the vessel could be performed only after it was exposed through a separate retroperitoneal approach.

FIGURE 66–12 Posteroanterior view of the pelvis showing the neurovascular structures in the sciatic notch.

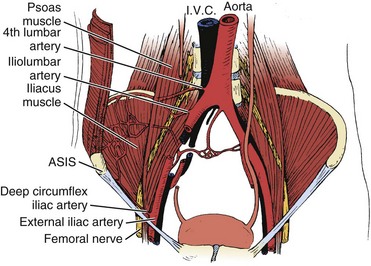

Three major arterial structures (Fig. 66–13) traverse the anterior surface of the iliacus muscle: the fourth lumbar artery, iliolumbar artery, and deep circumflex iliac artery. They provide an extensive blood supply to the iliacus, quadratus lumborum, and psoas muscles and frequently anastomose with each other. Harvesting of bone grafts from the inner table of the anterior ilium can damage this blood supply. Bleeding can be minimized by strict attention to subperiosteal stripping of the iliacus muscle.

Nerve Injury

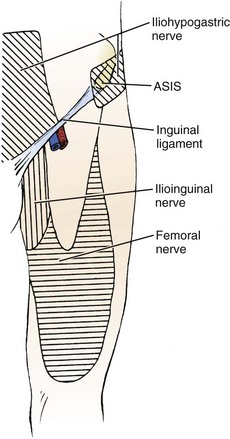

Ilioinguinal Nerve

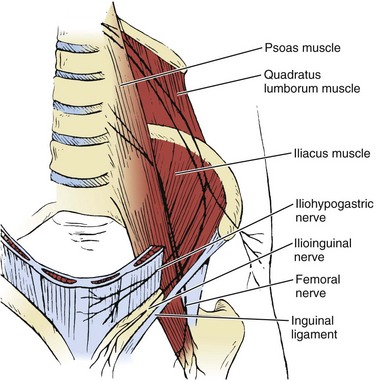

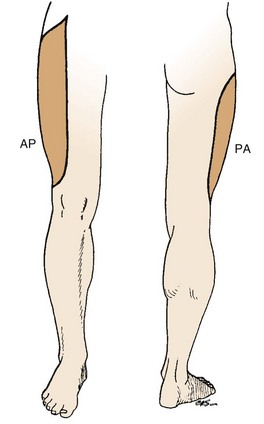

The ilioinguinal nerve is a branch of the first lumbar nerve, which crosses the psoas muscle and subsequently courses laterally over the iliacus and quadratus lumborum muscles (Fig. 66–14). When it reaches the level of the anterior iliac crest, it traverses the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, supplying their lower portions with motor fibers. It then travels under the external oblique muscle, enters the inguinal canal, and descends to supply sensation to parts of the penis, proximal and medial thigh (Fig. 66–15), scrotum, and adjacent abdomen. Vigorous retraction of the abdominal wall and iliacus muscles during bone graft harvest from the inner table of the anterior ilium was reported to have led to ilioinguinal neuralgia.10 Treatment typically consists of local nerve blocks and patience. Because prevention is preferable to treatment, gentle retraction of iliacus and abdominal wall muscles will minimize the risk of injury to this nerve.

Iliohypogastric Nerve

The iliohypogastric nerve courses slightly proximal to the ilioinguinal nerve (see Fig. 66–14) and supplies motor fibers to the lower portion of the abdominal wall and sensory fibers to the skin that surrounds the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest (see Fig. 66–15). Iliohypogastric neuralgia probably results from nerve retraction in a manner similar to that of ilioinguinal neuralgia.

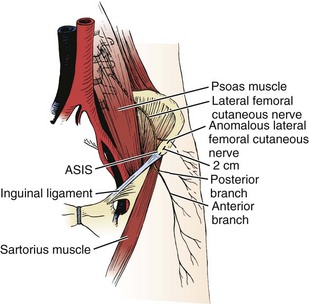

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve

The sole function of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is to supply sensation to the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 66–16). It first traverses the psoas muscle and then crosses the anterior surface of the iliacus muscle before passing into the thigh, near the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 66–17). Normally, the nerve passes beneath the inguinal ligament and the sartorius muscle, both of which attach to the anterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 66–17). An anatomic variant exists, in up to 10% of cases,11 in which the nerve crosses over the anterior iliac crest approximately 2 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 66–17), thus rendering the nerve prone to injury during harvesting of bone from the anterior iliac crest.

Paresthesias, pain, and numbness in the distribution of the nerve may occur12–16 after injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Its presentation, as classic meralgia paresthetica, is usually followed by resolution of symptoms and usually occurs within 3 months. However, this resolution occurs only if the injury is due to retraction, with subsequent neurapraxia. On the other hand, numbness may be permanent if the injury results from crushing or severing of the nerve as it crosses over the anterior iliac crest. Resolution of persistent pain and paresthesias may require local nerve blocks.

Sciatic Nerve

The sciatic nerve arises from branches of the sacral plexus (L4-S3), exits the pelvis to enter the gluteal region through the sciatic notch, and subsequently courses down the posterior thigh (see Fig. 66–12). This nerve may be injured in, or in close proximity to, the sciatic notch. The individual branches of the sciatic nerve may not coalesce to form the sciatic nerve itself until 1 to 5 cm distal to the proximal border of the sciatic notch (see Fig. 66–12). Therefore an injury to the nerve at the notch may not result in a complete sciatic nerve injury but may mimic a lumbosacral nerve root injury.

Superior Gluteal Nerve

The superior gluteal nerve courses along with the superior gluteal artery through the sciatic notch and supplies motor branches to the tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus muscles (see Fig. 66–12). Hip abductor weakness may result in injury to this nerve in the region of the sciatic notch.

Femoral Nerve

The femoral nerve (L2, L3, and L4) passes deep to the psoas muscle, courses over the iliacus muscle, and subsequently enters the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament (see Fig. 66–13). It supplies sensory fibers to the anteromedial thigh and medial lower leg and foot and innervates the muscles of the anterior compartment of the thigh (see Fig. 66–15). During harvesting of bone from the inner table of the anterior ilium, careful dissection and retraction near the iliac fossa can minimize the risk of injury to this nerve.

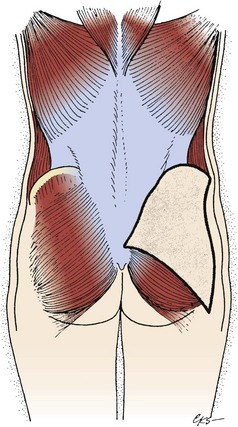

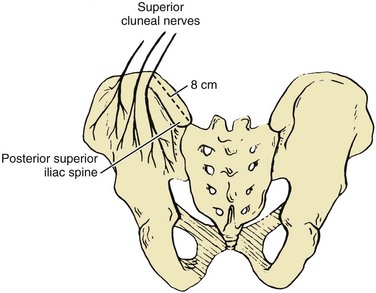

Superior Cluneal Nerves

Sensation to the majority of skin over the buttock is supplied by the superior cluneal nerves (Fig. 66–18), which are cutaneous branches arising from the first, second, and third lumbar nerve roots. They pierce the lumbodorsal fascia just superior to the posterior iliac crest and cross it at a point 8 cm lateral to the posterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 66–4). Numbness over the buttock from injury to these nerves is usually a minor complaint because of the extensive cross innervation of the skin of the buttock. However, painful neuromas that can be refractory to local injections of corticosteroids may occur and may require surgical excision for resolution of symptoms. Injury to these nerves may be minimized by staying 8 cm medial to the posterior superior iliac spine during the posterior approach to the iliac crest.

Hematoma

Bleeding from the harvested cancellous bone bed can be significant because the ilium is endowed with a rich vascular supply. Hematoma formation has been reported as high as 10% in patients whose donor site wounds were not drained.6,17,18 In another study19 it was shown that hematomas are more likely to occur after anterior bone grafting than from posterior bone grafting because the anterior iliac crest is superficial and local hemostasis from pressure tamponade is difficult to achieve. The incidence of hematoma by the posterior iliac crest is diminished by the hemostatic effect of pressure on posterior wounds from lying in the supine position. Many methods for ensuring hemostasis in donor sites exist including microcrystalline collagen,20,21 bone wax,5,8,22 thrombin-soaked gelatin foam,1 and injections of epinephrine and saline solution.23 Use of closed suction drainage for 1 to 2 days will decrease donor-site hematomas to less than 1%, and it is therefore generally recommended.

Gait Disturbance

Extensive stripping of the gluteus maximus muscle from the ilium may cause gluteal weakness, resulting in difficulty climbing stairs or rising from a sitting position. Abnormal gait has also been demonstrated in gait studies.24–26 This manifests as a dragging limp or abductor lurch (“gluteal gait”) owing to the extensive stripping of the outer table muscles, leading to weakness of the hip abductor muscles (primarily the gluteus medius). Minimizing the risk of occurrence of these gait disturbances requires secure reapproximation of the gluteal fascia to the periosteum of the iliac crest.

Cosmetic Deformity

Removal of cancellous strips or unicortical bone grafts from the ilium rarely results in a cosmetic deformity at the donor site. However, full-thickness grafts taken from the anterior ilium may alter the contour of the iliac crest and may leave an unsightly deformity. The subcrestal window method (see Fig. 66–2) avoids the iliac crest and therefore eliminates this problem. In addition, the trapdoor method (see Fig. 66–1) reconstitutes the crest and affords an excellent cosmetic result. Wolfe’s method2 results in a good cosmetic result by obliquely sectioning the crest with removal of a full-thickness graft and repair of the iliac crest with wire. In some patients, partial remodeling of the iliac crest after harvest may occur.27

Hernia

The firm attachment of the abdominal wall muscles (see Fig. 66–3) to the iliac crest normally prevents herniation of abdominal contents through it. In addition, the broad iliacus muscle, which lines the entire inner table of the iliac wing, prevents herniation through defects in the ilium. However, during harvesting of bone graft from the inner table of the anterior ilium, the fascial and muscular attachments of the abdominal wall and iliacus to the crest are detached. This “retaining wall” may therefore be weakened, allowing a hernia to occur. Herniation of abdominal contents has been reported28–36 only after harvesting of full-thickness iliac crest grafts. None has been reported with subcrestal windows (see Fig. 66–2). The best treatment is prevention, although various methods of repair have been reported.28,29,31,34,35 Secure reapproximation of the fascial and periosteal attachments using heavy sutures and drill holes, if necessary, may aid in preventing occurrence of a hernia.

Ureteral Injury

Because the ureter makes a sharp posterior angle (Fig. 66–19) toward the sciatic notch, just anterolateral to the gluteal vessels as they enter the notch, its proximity to the gluteal vessels renders it at risk with an injury to these vessels. Fulguration injuries to the ureter have been reported9 and have generally resolved without any treatment, despite the occurrence of significant clinical symptoms.

Peritoneal Perforation

Bone graft harvest from the inner table of the ilium poses a danger to the integrity of the peritoneum because it is closely applied to the inner surface of the abdominal wall and iliacus muscles (see Fig. 66–3). Perforation may occur after exuberant stripping of the iliac crest periosteum and the iliacus and abdominal wall muscles during exposure of the inner table.

Fracture

Stress fractures may occur following removal of full-thickness grafts from the anterior ilium.37 When harvesting large full-thickness grafts from the anterior ilium, it is important to leave a wide margin of bone between the resection site and the anterior superior iliac spine to prevent a stress fracture from the downward pull of the sartorius muscle (see Fig. 66–17) and rectus femoris muscles. The distal bone graft cut should not deviate anteromedially to avoid breaking through the iliac crest anteroinferior to the anterior superior iliac spine, thus leading to a bone avulsion.

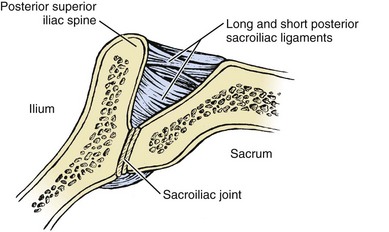

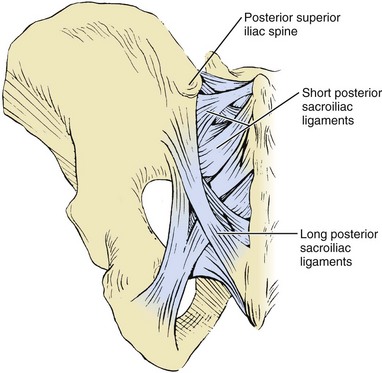

Sacroiliac Joint Injury

The majority of the stability of the sacroiliac joint arises from its strong posterior ligamentous complex. The complex is composed of the deeper interosseous ligaments (continuous with the posterior capsule) and the more superficial long and short sacroiliac ligaments (Figs. 66-20 and 66-21). These posterior ligaments may be damaged following removal of full-thickness grafts from the region of the posterior superior iliac spine. Although serious symptoms of instability from joint subluxation and dislocation have been reported,15,38,39 most symptoms of sacroiliac joint instability present as intermittent, mechanical pain.

Damage to Deep Neurovascular Bundles

Two deep neurovascular bundles surround the fibular shaft, both of which must be avoided during fibular bone graft harvest. One contains the deep peroneal nerve/anterior tibial artery/vein and lies medial to the fibular shaft on the interosseous membrane (see Fig. 66–9). This bundle may be damaged during stripping of the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus muscles if the surgeon strays anteromedially along the interosseous membrane. The second neuromuscular bundle contains the tibial/peroneal artery/vein and lies medial to the fibula (see Fig. 66–9). This bundle may be injured during stripping of the tibialis posterior muscle from the anteromedial surface of the fibular shaft.

Intercostal Neurovascular Injury

Errant periosteal stripping of the rib may result in injury to the intercostal neurovascular bundle, which is located in a groove on the posteroinferior edge of each rib (see Fig. 66–10). The artery and vein must be coagulated or tied off if hemorrhage occurs from an injury.

Clinical Recommendations

Ilium

When approaching the outer table of the anterior ilium, the incision should stop 2 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 66–17) to avoid injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and to the attachments of the inguinal ligament and the sartorius muscle. This will also help to avoid fracture of the ilium. Securely reapproximating the gluteal fascia to the iliac crest can prevent a gluteal gait. When taking bone graft from the outer table, avoid penetrating the inner table to prevent injury to the neurovascular structures that lie within the iliac fossa overlying the iliacus muscle (see Figs. 66-3, 66-13, and 66-17). These structures include the fourth lumbar, iliolumbar, and deep circumflex iliac arteries and the lateral femoral cutaneous, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and femoral nerves. Careful retraction of the iliacus and abdominal wall muscles may prevent injury to the peritoneum and the nerves that overlie the iliacus muscle when the inner table of the anterior ilium is exposed (see Fig. 66–3). The risk of herniation of abdominal contents through defects in the iliac crest (see Fig. 66–3) can be decreased through securely closing the fascia of the abdominal wall muscles. Strict attention to subperiosteal dissection of the ilium minimizes bleeding and the risk of hematoma formation. Anteriorly (see Fig. 66–13), this includes attention to the fourth lumbar, iliolumbar, and deep circumflex iliac arteries, Posteriorly (see Fig. 66–12), it includes attention to the superior gluteal artery. The incidence of significant hematoma formation can be reduced by suction drainage. When approaching the posterior ilium,4 a limited incision (see Fig. 66–4) within 8 cm lateral to the posterior superior iliac spine will avoid injury to the superior cluneal nerves, thereby preventing formation of painful neuromas. The sciatic notch should be avoided because the ureter, sciatic nerve, and superior gluteal nerve and artery lie in close proximity to this structure (see Figs. 66-4, 66-12, and 66-19). In addition, attempts should be made to avoid the posterior sacroiliac ligamentous structure to avoid sacroiliac joint instability when taking full-thickness grafts from the posterior ilium (see Figs. 66-20 and 66-21).

Fibula

By resecting the fibula no closer than 10 cm proximal to the ankle joint, thereby avoiding the syndesmosis, one may prevent instability to the ankle joint. Meticulous subperiosteal dissection will help avoid injury to neurovascular bundles (see Fig. 66–9).

Rib

To avoid the most common complications of injury to the lung and to the intercostal neurovascular bundle (see Fig. 66–10), subperiosteal exposure of the rib must be done. Injecting long-acting anesthetic near the costovertebral junction before wound closure may minimize postoperative pain and splinting.

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Coventry MB, Topper EM. Pelvic instability: A consequence of removing iliac bone for grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:83-101.

Excellent review of pathoanatomy of pelvic instability after iliac bone graft harvesting.

2 Cowley ST, Anderson LD. Hernias through donor sites for iliac bone grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1023-1025.

More recent review of abdominal hernias through iliac donor sites and recommendations for repair.

3 Dick IL. Iliac bone transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:1-14.

Solid review of the various uses for iliac bone graft transplantation.

4 Kurz LT, Garfin SR, Booth RE. Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: A review of complications and techniques. Spine. 1989;14:1324-1332.

Excellent general review of complications and techniques of iliac bone graft harvesting.

5 Stoll P, Schilli W. Long-term follow-up of donor and recipient sites after autologous bone grafts for reconstruction of the facial skeleton. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:676-677.

Good review of long-term follow-up of donor and recipient sites.

1 Scott W, Peterson RS, Grant S. A method of procuring iliac bone by trephine curettage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1949;31:860.

2 Wolfe SA, Kawamoto HK. Taking the iliac bone graft: A new technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:411.

3 Kurz LT, Garfin SR, Booth RE. Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: A review of complications and techniques. Spine. 1989;14:1324-1332.

4 Kurz LT. Iliac bone grafting: Techniques and complications of harvesting. In: Garfin SR, editor. Complications of Spine Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989:323-341.

5 Dawson EG, Lotysch MIII, Urist MR. Intertransverse process lumbar arthrodesis with autogenous bone graft. Clin Orthop. 1981;154:90-96.

6 DePalma A, Rothman R, Lewinnek G, et al. Anterior interbody fusion for severe cervical disc degeneration. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;184:755-758.

7 Flint M. Chip bone grafting of the mandible. Br J Plast Surg. 1964;17:184-188.

8 Bloomquist DS, Feldman GR. The posterior ilium as a donor site for maxillofacial bone grafting. J Max Surg. 1980;8:60-64.

9 Escalas F, DeWald RL. Combined traumatic arteriovenous fistula and ureteral injury: A complication of iliac bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:270-271.

10 Smith SE, De Lee JC, Ramamurthy S. Ilioinguinal neuralgia following iliac bone-grafting: Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1306-1308.

11 Ghent WR. Further studies on meralgia paresthetica. Can Med Assoc J. 1961;85:871-875.

12 Goldner JL, McCollum DE, Urbaniak JR. Anterior disc excision and interbody spine fusion for chronic low back pain. Presented before the AAOS Symposium on the Spine. 1967:pp 111-131.

13 Kambin P. Anterior cervical fusion using vertical self-locking T-graft. Clin Orthop. 1980;153:132-137.

14 Massey EW. Meralgia paresthetica secondary to trauma of bone graft. J Trauma. 1980;20:342-343.

15 Stauffer RN, Coventry MB. Anterior interbody lumbar spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:756-768.

16 Weikel AM, Habal MB. Meralgia paresthetica: A complication of iliac bone procurement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60:572-574.

17 Sacks S. Anterior interbody fusion of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:211-223.

18 Stauffer RN, Coventry MB. Posterolateral lumbar spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:1195-1204.

19 Dick IL. Iliac bone transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:1-14.

20 Cobden RH, Thrasher EL, Harris WH. Topical hemostatic agents to reduce bleeding from cancellous bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:70-73.

21 Mrazik J, Amato C, Leban S, et al. The ilium as a source of autogenous bone for grafting: Clinical considerations. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:29-32.

22 Abbott LC. The use of iliac bone in the treatment of ununited fractures. AAOS Instructional Course Lectures, vol 2. St. Louis: CV Mosby. 1944:pp 13-22.

23 Pelvis. In: Goldstein LA, Dickerson RD, editors. Atlas of Orthopaedic Surgery. New York: CV Mosby; 1974:450-453.

24 Abbott LC, Schottstaedt ER, Saunders JB, et al. The evaluation of cortical and cancellous bone as grafting material. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1947;29:381-414.

25 Converse JM, Campbell RM. Bone grafts in surgery of the face. Surg Clin North Am. 1954;34:375-401.

26 Stoll P, Schilli W. Long-term follow-up of donor and recipient sites after autologous bone grafts for reconstruction of the facial skeleton. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:676-677.

27 Rappaport I, Boyne PV, Nethery J. The particulate graft in tumor surgery. Am J Surg. 1971;122:748-755.

28 Bosworth D. Repair of herniae through iliac crest defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37:1069-1073.

29 Challis JH, Lyttle JA, Stuart AE. Strangulated lumbar hernia volvulus following removal of iliac crest bone graft. Acta Orthop Scand. 1975;46:230-233.

30 Cowley ST, Anderson LD. Hernias through donor sites for iliac bone grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1023-1025.

31 Froimson AI, Cummings AGJr. Iliac hernia following hip arthrodesis. Clin Orthop. 1971;80:89-91.

32 Lewin ML, Bradley ET. Traumatic iliac hernia with extensive soft tissue loss. Surgery. 1949;26:601-607.

33 Lotem M, Moor P, Haimoff H, et al. Lumbar hernia at an iliac bone graft donor site. Clin Orthop. 1972;80:130-132.

34 Oldfield MC. Iliac hernia after bone grafting. Lancet. 1945;248:810-812.

35 Pyrtek LJ, Kelly CC. Management of herniation through large iliac bone defects. Ann Surg. 1960;152:998-1003.

36 Reid RL. Hernia through an iliac bone graft donor site. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50:757-760.

37 Guha SC, Poole MD. Stress fracture of the iliac bone with subfascial femoral neuropathy: Unusual complications at a bone graft donor site: Case report. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36:305-306.

38 Coventry MB, Topper EM. Pelvic instability: A consequence of removing iliac bone for grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:83-101.

39 Lichtblau S. Dislocation of the sacroiliac joint: A complication of bone grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:193-198.

-inch straight osteotome. PSIS, posterior superior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

-inch straight osteotome. PSIS, posterior superior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.