16 Team Relationships

By its very nature, and in fact by legislative decree in the case of hospice, the discipline of palliative care is a team sport. The overall goal of teamwork is to enhance patient care through team performance, member satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Through a cyclic process of “forming, storming, norming, and performing,”1 teams that are well-formed and well-maintained enhance the delivery of pediatric palliative care by far more than the sum of the individual disciplinary parts. Nevertheless, highly functional teams are not automatic—their creation and ongoing survival and growth require high-level, multimodal skills. This chapter will explore the basic types and dynamics of teams, their critical importance in pediatric palliative care, typical features of functional and dysfunctional teams, and practical strategies to prevent or remedy dysfunction to preserve and protect teams and their members.

Team Structures

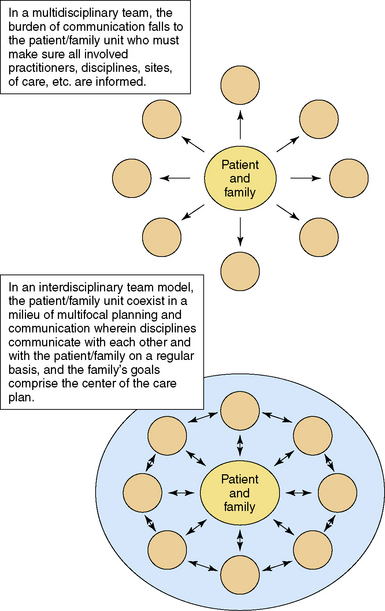

Teams come in many flavors. Multidisciplinary teams are groups of individual practitioners who come together to report on what each is doing and work side by side but not necessarily together.2 In multidisciplinary teams, professional identities are primary while team membership is a secondary priority. Leadership is generally hierarchical, and practitioners function as wedges in a pie.3 Partly because these teams rarely meet face to face to discuss the needs of mutual clients, the multidisciplinary model is not a good fit for palliative care because the lack of regular communication increases burdens on families who become responsible for keeping their care professionals apprised of changing symptoms and treatments (Fig. 16-1).4

Most palliative care teams are self-described as interdisciplinary. In this model, different professionals combine resources and talents to deliver care in an interactive process by which collaboration reveals goals that cannot be delivered by one discipline alone,5 and the synergy resulting from collaboration creates an “active, ongoing, productive process.”6 Team members engage in joint work from different orientations,7 and the objective is to arrive at effective treatment decisions after considering input from all members. Leadership of interdisciplinary palliative care teams is often task-dependent and decisions are usually made by consensus;8 this process enables focus on medical concerns as well as wider issues of comfort and total patient-centered care—a founding principle of specialist palliative care practice.9

As mentioned above, the interdisciplinary team model of care is the standard of care in hospice, which is one of the only settings in the United States where interdisciplinary teamwork is regulated.10,11 Functional interdisciplinary care can actually be measured through the Index of Interdisciplinary Collaboration. This instrument assesses teams based on a model of successful collaboration whose components are interdependence, newly created professional activities, flexibility, collective ownership of goals, and reflection on process.12 Compared to multidisciplinary teams, interdisciplinary teams have been rated by members as higher in coherence, sense of responsibility, work climate, internal organization, and communication.13 A true interdisciplinary team illustrates that the function of a hand is far more than the sum of each individual digit.3,14 Most interdisciplinary teams are comprised of members who belong primarily to that team, service, program, or division.

Cross-functional teams are a subset of interdisciplinary teams with potential relevance in pediatric palliative care. Arising from the business world out of organizational theory, cross-functional teams are assembled to create sets of skills for a particular purpose. Members cover each other’s weaknesses and maximize strengths as the team together takes responsibility for the well-being of a patient and family. In this way, resources are multiplied by the overlap of roles and a unique forum for problem-solving is developed.14 A pediatric palliative care program in a large children’s hospital discovered that families receiving care were being balance-billed when their insurance benefits did not cover palliative care services; worse yet, families were also receiving bills after their children had died. The program put together a cross-functional team, which included billing and finance personnel, a social worker, a parent liaison from the hospital’s parent advisory committee, a department administrator, and leadership from the clinical palliative care program, to tackle the issue. Over an 18-month period, the team worked through the logistical confines of the hospital’s accounting methods to create a system that satisfied everyone, especially the families. Some pediatric palliative care teams themselves can be described as cross-functional; in general, these are interdisciplinary teams at the core but also include members from other disciplines, departments, divisions, service lines, or the community, who have other job responsibilities and reporting structures but come together for a defined purpose or patient population.

Benefits for pediatric palliative care teams are many:

From an organizational standpoint, cross-functional palliative care teams can enhance an organization’s innovative capacities to match the organization to the environment by bundling a large range of discipline-based skills and competencies in different ways, using different team members.15

The last team type is transdisciplinary. This model is gaining in popularity, though not as commonly in healthcare. The fundamental concept is one of role release in which there exist few seams among member functions. Roles and responsibilities are shared and often blurred.3,14 Members of transdisciplinary teams have been heard to say, “Everyone on this team is a little bit nurse, a little bit social worker, a little bit physician. Whoever is in the clinical situation does what needs to be done since we all have a good basic knowledge of what our colleagues do.” While this approach has its advantages, problems with role definition can lead to significant impairments in team functioning in palliative care; such potential downsides will be discussed later in this chapter.

Benefits and Challenges of Team-Based Palliative Care

Despite this lengthy list of benefits, some authors believe that the emphasis on the interdisciplinary team in palliative care is faulty. For example, Cott asserts that the value of team presupposes untested and perhaps unsustainable assumptions: that team members have shared understandings of norms, values, and roles; that the team functions in a cooperative, egalitarian, interdependent manner; and that the combined effects of shared, cooperative decision making are of greater benefit to the patient than the individual effects of the disciplines on their own.24 At the very least, the as-yet untested benefits in pediatric palliative care necessitate that the team model be created, maintained, and sustained in the most productive and best way possible to maximize whatever potential benefits may be validated in actual practice.

Teams in palliative care have a number of specific challenges that are not faced as consistently by other healthcare teams. From the start members must form solid relationships with new colleagues to build an effective working group, acclimate to a field of work with a high emotional burden, and tolerate the significant uncertainty of practicing without defined standards compared to other medical fields.4,13 The ever-increasing complexity of palliative medicine calls, in turn, for recognition of the increasing complexity and multiplicity of teams.25 Teams must navigate more complex patient needs and work with more informed patients and families playing more significant roles in their own care—both a blessing and a challenge—in an environment in which ambiguity and uncertainty are the norms.

The context in which care is given is also increasing in complexity, requiring flexibility related to the diversity of location, culture, family structure, communities, privacy, and interconnectedness.25 Practical conflicts exist as well. Team members must handle ever-changing communication patterns involving the use of alien technology and differences in terminology among disciplines.26 Health-related priorities, targets, resources, and budgets are generally not set by palliative care teams, often resulting in scarcity of resources.26 Increased access and equity, particularly as offered by community-based services, result in a larger service area with limited resources.4 In fact, despite the continual change occurring for patients and families, the availability of resources for care is generally either constant or shrinking.15

In addition to the challenges inherent in clinical work, team functioning itself may be in conflict with the core values of palliative care. For instance, the philosophy of palliative care may be at odds with the clarification of team roles and procedures,4 and the focus on team function may end up protecting team members rather than supporting patient and/or family needs.26 Conflict may also occur between the democracy of palliative care teams and the traditional medical model.

Forming and Sustaining Teams: Recipes for Success and Failure

The effectiveness of any team collaboration can be affected by structural characteristics, which are influenced by organizational processes contributing to the team’s development and maintenance. Clearly, strong and visionary leadership is necessary for any team to succeed, and its importance cannot be emphasized enough. Box 16-1 describes some of the qualities of true team-centered leaders, which enhance the probability of developing and sustaining high-functioning teams. Further positive influences on team effectiveness comes from manageable caseloads, supportive and collaborative organizational culture, administrative support, professional autonomy, and time and/or space for collaboration.6,7 The larger the team, and the more disciplines involved, the more time that team needs to achieve functionality and growth.7

In a survey of four nonprofit health care institutions, two of them pediatric, Proenca established that team empowerment is the mechanism through which team context and team atmosphere affect job satisfaction and organizational commitment.28 This is helpful news for teams because it suggests that modifications of context and atmosphere that facilitate empowerment will lead to positive outcomes of improved satisfaction and organizational commitment. Said another way, direct strategies to empower team members can overcome a large number of variables that likely can’t be modified or eliminated in daily life on a palliative care team.

Oliver et al used a modified Index of Interdisciplinary Col-laboration and found that perceptions of interdisciplinary team collaboration can be measured, and that educational training in a specific discipline and clinical training do not create variance in perceptions of that collaboration. Instead, varied perceptions come from the interdisciplinary nature of the particular team.10 In other words, it might be thought that collaboration is affected by the varied disciplines or training backgrounds or cultures of the individual team members. But it appears as though the team structure, leadership, empowerment, and functionality influence how members perceive how well the team collaborates. This again is heartening news for interdisciplinary and/or cross-functional teams because it suggests that effort directed at team functioning will overcome differences in individual background and training, which might seem to affect collaboration negatively.

Team composition

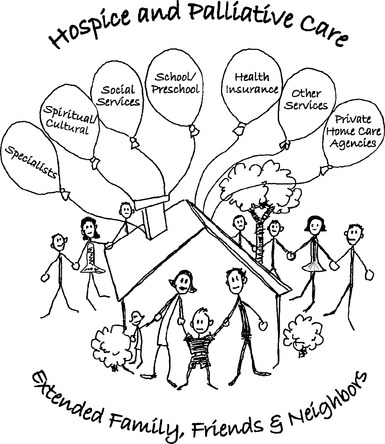

The ideal makeup of a pediatric palliative care team will necessarily vary depending on site, goals, and scope of services, as well as on resources. Ideally, every team will be made up of medical; nursing; psychosocial, including social work, child life, and psychology; and spiritual and bereavement care; and will be able to access high-quality adjunct services such as pharmacology, nutrition, expressive therapy, rehabilitation, and education. When fully actualized, a pediatric palliative care team is like a tapestry in which different colors of threads are interwoven to produce a complete picture. At times one color—or one discipline—may be more prominent while others take a more background role. But the presence of each makes the tapestry complete when the weaving exists and comes together around a child and family’s goals of care (Fig. 16-2).

Parents, as partners with the palliative care team, can play an important role. The child and family are the center of the unit of care, but are not truly members of the palliative care team (see Chapter 6). Nevertheless, parents and even patients themselves can and should play important roles. Mature patients, bereaved parents, or parents of chronically ill children, with appropriate training, can make excellent advisers to palliative care teams in terms of advocacy, clinical programming, and research initiatives. Parent and patient volunteers can take on team-based tasks such as assisting with bereavement outreach, memorial service planning, newsletter production and distribution, holiday or birthday and/or death day card writing. In addition, many hospitals and community agencies have mentor programs through which parents can be paired with others in similar circumstances to offer support and guidance. Resources such as the Institute for Family-Centered Care (www.familycenteredcare.org) provide excellent materials on training parent advocates to be effective members of the healthcare team.

Frameworks of Team Function and Dysfunction

The ways in which a palliative care team functions are influenced by a multitude of factors.

Based on purpose or mission, a team must have established goals or tasks and clearly defined objectives, and the strategies to achieve these, all of which need consensus and clarity.5,25

Interdisciplinary teams in particular need clearly defined internal and external role expectations. In practice, there is actually little congruence between the way a group of professionals defines its own roles and the way others define them.27 Thus, because of the nature of the work, palliative care teams must delineate clear internal lines of responsibility and norms the unwritten rules governing the behavior of people in groups–before navigating the vague and changing environments in which they integrate.

Communication is perhaps the single most important factor in team success. Palliative care teams must establish defined communication patterns. At a minimum, this process should involve a clear definition of tasks and of responsibility and accountability for task completion.25 Team members need accurate, common language for transmitting information and an agreed-upon philosophy of care, both of which incorporate mechanisms and capacity for team members to ascertain what others need to know to practice effectively.4

Other core concepts for functional teams include recognizing the specific personal contribution of every team member in their discipline, while respecting the same in others.25 It is important to have a lack of hierarchy but a clear decision-making process. This allows for collaborative decision making while minimizing confusion about how things get decided. A culture that prioritizes autonomy, has realistic work expectations, and encourages high levels of personal feedback from colleagues as well as from patients and families29 will strengthen the team. The successful team needs strong collaborative leadership that nurtures an atmosphere to cope with the specific challenges of palliative care. Factors particular to palliative care team success are procedures for evaluating effectiveness and quality of care, recognition of the contribution of patients in furthering professional understanding, and bereavement care of staff25 (Box 16-2). Particularly in the challenging world of palliative care, team function and dysfunction come in many flavors and have been investigated by several authors. Some general observations about teams and categories of dysfunction in team based-care:

Examining team health in pediatric palliative care

As is clear from the previous section, there are a multitude of frameworks in which to dissect the structure and function of interdisciplinary teams. In The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Lencioni posits a helpful construct to discuss pediatric palliative care teams more specifically. Lencioni’s five dysfunctions build on each other in pyramid fashion. An absence of trust, created from an unwillingness to be vulnerable, creates fear of conflict, which results in veiled discussions and guarded comments. This environment generates lack of commitment, which progresses to avoidance of accountability resulting from lack of buy-in; and then to inattention to results, putting individual or divisional needs above those of the team. In contrast, truly cohesive teams trust one another, engage in unfiltered conflict, commit to decisions and action plans, hold each other accountable for delivering, and focus on the achievement of collective results.34

The costs of dysfunction in interdisciplinary teams can be extremely high. In addition to ineffectiveness and team member dissatisfaction, poorly functioning teams impact the patients and families we serve. Patient reactions to team dysfunction can lead to splitting or increased dependency on team members. For example, during the collective indecision phase of team development, patients and/or their families may ask multiple staff members the same questions and get different answers, leading to more anxiety. Even more significantly, patient or family lack of confidence in their care team may increase patient symptomatology.27 Ultimately, of course, unnoticed or uncorrected dysfunction can lead to an implosion that results in the total dissolution of even the most well-intentioned group of like-minded people. Similar to what can be seen with individual patients and families, this so-called demoralization syndrome of teams stems initially from poor leadership and unreasonable burdens, and results in absenteeism, apathy, resistance to change, and deep sadness. Untreated, it progresses to a fatal loss of vision or loss of belief that objectives are worth striving for or even achievable.25

Lack of Commitment

In addition to clear, realistic, well-defined goals, commitment to supportive and collaborative relationships is equally important to healthy team functioning. As noted by Papadatou, “While team goals orient our actions, supportive and collaborative relationships help us to achieve them.”35 In fact, the two may be considered interdependent as the more supported we are by team members, the more likely we are to commit ourselves to work tasks and to the development of compassionate relationships. Thus committed care providers are dedicated to meaningful goals, rely upon each other in order to achieve them, and are mutually supported through the process. Four specific aspects of support that we seek and expect to receive from colleagues are informational support, instrumental support, emotional support, and support in meaning construction (Table 16-1). Each team values and encourages different aspects of support at different times. For mutual support to be effective, it must be timely and responsive to the specific needs and preferences of care providers, which vary from one team to another and at different times under different circumstances. Team functioning may be compromised when such support is unavailable or unresponsive to the needs of team members.

| Informational support | Involves the exchange of information about the people served and the team’s mode of operation; it comprises mutual feedback about and evaluation of individual or team performance with opportunities to expand one’s knowledge and skills. |

| Instrumental support | Involves helping each other with practical issues such as sharing the workload, and the coordination of efforts toward the achievement of specific tasks. Shared goals, role clarity, and trust in each other’s knowledge and skills enhance this form of support. |

| Emotional support | Involves opportunities for sharing personal feelings and thoughts in a safe environment in which one feels heard, understood, valued, and appreciated. Sometimes the presence of another colleague during stressful moments is all that is needed. |

| Support in meaning construction | Involves opportunities to reflect on and work through work-related experiences and invest individual and collective efforts with meaning. Care providers help each other understand their responses, correct distortions, and reframe situations in ways that make sense to them. |

Adapted from Papadatou D. In the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and bereaved. New York, 2009, Springer Publishing.

Avoidance of Accountability and Conflict

Every PPC team needs to have a foundation of trust and openness among its members, wherein individuals can express their vulnerability with each other, disagree openly and remain respectful of one another. It is no surprise that team members who trust each other function effectively together to achieve their goals. This does not mean that they always agree with each other, but rather that there exists a basis of respect and openness that allows for expression of different views. Healthy discussion and effective resolution of conflict will enhance the level of trust and communication within the team.34

Few if any palliative care team members choose conflict over collaboration, yet conflict is a given part of the life of any team. However, the way in which the conflict is handled between individuals and within the team can either strengthen or damage the whole group. Not uncommonly, in a misguided effort to be collaborative, the actual heart of the conflict may not be discussed and the source never identified or verbalized. When this occurs, people often become frustrated as they desperately try but fail to communicate without dealing with the conflict.34 This is the proverbial elephant in the room that palliative care clinicians are so skilled at helping families face. Under the guidance of strong leadership, teams must draw upon their individual and collective skills in this area in order to address difficult issues in conflict resolution. Some helpful interventions are focusing on learning more about others’ perspectives and using language that is open and less blaming. These strategies, explored in more detail later in this chapter, will go a long way in improving the functioning of team as a whole.34

Practical applications of conflict resolution, encouragement of open and respectful debate, and using collaborative communication are important aspects in developing and maintaining an effective team.36 A well-functioning team should be able to discuss disagreements openly and accept that there are often different ways to solve a problem. This environment allows individuals to be accountable for their mistakes, to avoid shame or punishment, and to use these situations as learning experiences for the team as a whole. An attitude of open discussion when things do not go well should be encouraged and supported both in word and deed. In one team interaction a clinician was offended by what was meant as an innocent action by another team member. She addressed this directly in the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, and both clinicians shared their view of what had happened. Because this was not the way the team had operated previously, the process was somewhat uncomfortable for the individuals and the team as a whole. However, it was a growth experience for all. It did resolve the issue, and provided an example of how conflicts can be dealt with in a healthy way.

Solutions and take-home messages

Fortunately, the picture is not one of inevitable failure. In fact, with attention to the issues, strong leadership, training, and a few key tactics, dysfunctional outcomes can be avoided relatively easily. Based on the discussions herein, a number of practical strategies can be outlined for team members and leaders to employ to create healthy and sustainable teams while avoiding the pitfalls that sink many well-meaning teams and organizations. Box 16-3 contains a list of some of the key points from this chapter to provide direction for pediatric palliative care teams.

BOX 16-3 Creating Healthy PPC Teams

Team Self-Care Planse

Pediatric palliative care team members work hard to develop and implement excellent, individualized, child-centered care plans. However, rarely if ever do they spend time working on care plans for themselves. Pediatric palliative care can exact a heavy toll on professionals.37 Self-care plans are a formal way to examine how individuals can help themselves maintain healthy lives while working so closely with loss and sadness. The concept of the self-care plan is not new, yet its formal development and practical use are recent. When carefully developed, these documents can promote and sustain highly successful teams.

Summary

As with many core concepts in pediatric palliative care, teamwork is not usually formally taught. Instead, most clinical teams learn these important skills by trial and error or by example, some good, some less than ideal. However, much more knowledge and training is available to guide the creation of unified, healthy, high-quality, effective and empowered interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care teams. “Providing team-based palliative care needs to be more than a set of assumptions about how teams can operate. … We need to move beyond the assumption that teams will operate effectively and toward a position that looks at their critical operation.”26 To place the primary focus of teamwork where it most belongs, team leaders and members would do well to remember that teams will form and reform “and change like the patterns in a kaleidoscope in the changing scenarios in healthcare systems—but what unifies the whole enterprise is the patient whose story is the common thread.”25

1 Tuckman B. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bulletin. 1965;63(6):384-399.

2 Lee S. Interdisciplinary teaming in primary care: a process of evolution and resolution. Soc Work Health Care. 1980;5(3):237-244.

3 Crawford G.B., Price S.D. Team working: palliative care as a model of interdisciplinary practice. MJA. 2003;179:S32-S34.

4 Street A, Blackford J: Communication issues for the interdisciplinary community palliative care team.

5 Rubin I., Beckhard R. Factors influencing the effectiveness of health teams. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1972;50(3):317-335.

6 Bronstein L.R. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work. 2003;48(3):297-306.

7 Wittenberg-Lyles E.M., Oliver D.P., Demiris G., Courtney K.L. Assessing the nature and process of hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. J Hospice Palliat Nurs. 2007;9(1):17-21.

8 Cummings I. The interdisciplinary team. In: Doyle D., Hanks G.W., MacDonald N., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

9 Arber A. Team meetings in specialist palliative care: asking questions as a strategy within interprofessional interaction. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(10):1323-1335.

10 Oliver D.P., Wittenberg-Lyles E.M., Day M. Variances in perceptions of interdisciplinary collaboration by hospice staff. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(4):275-280.

11 HCFA. Medicare Program Hospice Care: Final Rule. Health Care Financing Administration, Agency for Health Policy Research, 1983.

12 Bronstein L.R. Index of interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work Res. 2002;26(2):113-126.

13 Junger S., Pestinger M., Elsner, et al. Criteria for successful multiprofessional cooperation in palliative care teams. Palliat Med. 2007;21:347-354.

14 Parker G.M. Cross-functional teams: working with allies, enemies and other strangers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1994.

15 Hyland P., Davison G., Sloan T. Linking team competencies to organizational capacities in health care. J Health Organ Manag. 2003;17(3):150-163.

16 Kemp K.A. The use of interdisciplinary medical teams to improve quality and access to care. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(5):557-559.

17 Dyeson T.B. The home health care team: what can we learn from the hospice experience? Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2005;17:125-127.

18 Reese D.J., Raymer T.B. Relationships between social work involvement and hospice outcomes: results of the National Hospice Social Work Survey. Soc Work. 2004;49:415-422.

19 Opie A. Nobody’s asked me for my view: users’ empowerment by multidisciplinary health teams. Qual Health Res. 1998;8(2):188-206.

20 Jack B., Hillier V., Williams A., Oldham J. Hospital-based palliative care teams improve the symptoms of cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2003;17(6):498-502.

21 Higginson I.J., Finlay I.G., Goodwin D.M., et al. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(2):150-168.

22 Schrader S.L., Horner A., Eidsness L., et al. A team approach in palliative care: enhancing outcomes. S D J Med. 2002;55(7):269-278.

23 Jack B., Hillier V., Williams A., Oldham J. Hospital-based palliative care teams improve the insight of cancer patients into their disease. J Palliat Med. 2004;18(1):46-52.

24 Cott C. Structure and meaning in multidisciplinary teamwork. Sociol Health Illn. 1998;20(6):848-873.

25 Lickiss J.N., Turner K.S., Pollock M.L. The interdisciplinary team. In: Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherny N., Calman K., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. ed 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:42-46.

26 O’Connor M., Fisher C., Guilfoyle A. Interdisciplinary teams in palliative care: a critical reflection. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2006;12(3):132-137.

27 Lowe J.I., Herranen M. Conflict in teamwork: understanding roles and relationships. Soc Work Health Care. 1978;3(3):323-330.

28 Proenca E.J. Team dynamics and team empowerment in health care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(4):370-378.

29 Graham J., Ramirez A.J., Cull A., et al. Job stress and satisfaction among palliative physicians. Palliat Med. 1996;10:185-194.

30 Vachon M.L. Staff stress in hospice/palliative care: a review. Palliat Med. 1995;9(2):91-122.

31 Larson D. The helper’s journey: working with people facing grief, loss and life-threatening illness. Champaign Ill: Research Press, 2003.

32 Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: Jason Aronson, 1978.

33 Butterill D., O’Hanlon J., Book H. When the system is the problem, don’t blame the patient: problems inherent in the interdisciplinary inpatient team. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37:168-172.

34 Lencioni P.M. The five dysfunctions of a team. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

35 Papadatou D. the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and bereaved. New York: Springer Publishing, 2009.

36 Feudtner C. Collaborative communication in pediatric palliative care: a foundation for problem-solving and decision-making. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:587-607.

37 Sourkes B., Frankel L., Brown M., et al. Food, toys and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35(9):357.

38 Baggs J.G., Norton S.A., Schmitt M.H., Seller C.R. The dying patient in the ICU: role of the interdisciplinary team. J Crit Care Clinics. 2004;20:525-540.

39 Cohen L., O’Connor M., Blackmore A.M. Nurses’ attitudes towards palliative care in nursing homes in Western Australia. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2002;8(2):610-620.

40 Head B. The blessings and burdens of interdisciplinary teamwork. Home Healthc Nurse. 2002;20(5):337-338.