Chapter 128 Taxus brevifolia (Pacific Yew)

Taxus brevifolia (family: Taxaceae)

General Description

General Description

Paclitaxel (Taxol) and complex diterpenoid taxanes are compounds found in Taxus brevifolia. Docetaxel (Taxotere) is a semisynthetic agent similar in action to paclitaxel derived from 10-deacetyl baccatin III, a taxane isolated from the needles of Taxus baccata, the English yew. Prior to their formal drug development, these compounds were cited as among the most promising plant compounds tested for anticancer properties in 1990.1 The Pacific yew was first collected in 1962 by a U.S. Department of Agriculture team in Washington State as part of the large natural products screening program of the U.S. National Cancer Institute. Confirmed activity by a bark extract against the KB cell line in tissue culture was reported in 1964. Isolation studies began in 1965, and by 1971, Wall et al2 at the Research Triangle Institute (Durham, N.C.) had identified paclitaxel as the active constituent.2 Paclitaxel became big news in 1989, when investigators at the Johns Hopkins Oncology Center in Baltimore reported a 30% response rate in cases of refractory ovarian cancer, a remarkable rate for this type of cancer.3 The development of docetaxel began in 1981 in France. Taxanes used in conjunction with chemotherapy and irradiation have demonstrated improved results as compared with either of these therapies alone as well as better tolerance of these therapies.3a

Chemical Composition

Chemical Composition

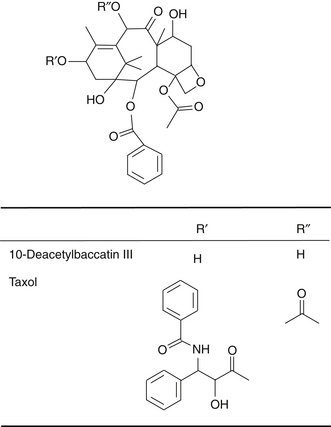

The Pacific yew is poisonous because it contains at least 11 alkaloids, known collectively as taxines. The structure of only two of the alkaloid constituents is known: taxine A, which accounts for 30%, and taxine B, which accounts for 2%. Paclitaxel (Figure 128-1) is a pseudoalkaloid but not a constituent of taxine because its nitrogen is acylated with benzoic acid and has no basic principle. The concentration of paclitaxel in yew bark is low, only 0.01%.

History and Folk Use

History and Folk Use

Historically, the yew has been highly valued for its dense, resilient, decay-resistant, tight-grained wood and its medicinal properties. The Greeks named the yew toxus in reference to its use for making a strong bow (toxon), and its poisonous nature (toxikon).2 It was used as an animal and fish poison by primitive cultures as well as for murder and suicide. In the first century AD, Claudius suggested its use as an antidote for viper bites. Europeans used it as an abortifacient as well as to treat heart ailments and hydrophobia.2 Native Americans used the yew for many ailments, as follows:

Women ate yew berries to prevent conception. Youths rubbed smooth sticks of yew on their developing bodies to gain its strength. Both the bark and the leaves have been brewed for tea, and powders have been made from the bark alone. The fleshy red aril (berry) that surrounds the seed is not poisonous, although the seed itself is.4

There is a lot of folklore about the yew’s supernatural powers. Because it is a slow-growing, long-lived tree, it was associated with immortality and used in spells to raise the dead.5 Because it was regarded as among the most potent of trees for protection against evil, it was considered unlucky to cut down or damage a yew tree. Many were planted in churchyards/graveyards and alongside homes for protection. Specimens survive today in spite of main trunks being hollowed out from decay following hundreds of years of existence.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Paclitaxel’s anticancer action is unique in that it inhibits cell division by promoting the formation of microtubules, the rodlike structures that function as a cell skeleton, making cells more stable and resistant to depolymerization. In contrast, other anticancer phytoagents (e.g., colchicine and vinca alkaloids) induce the polymerization of microtubules. In addition, under the influence of paclitaxel, the microtubules polymerize independently of the microtubule-organizing center, which is in a perinuclear area, and instead localize predominantly in the cell’s periphery.6 This interferes with the mitotic spindle and selectively blocks cells in the G2 and M phases of the cell cycle, the most radiosensitive phases. Additionally, paclitaxel induces the formation of abnormal spindle asters that do not require centrioles for enucleation and are reversible after treatment.7–10 Furthermore, in vivo, paclitaxel has demonstrated an ability to activate the local release of an apoptosis-inducing cytokine.11 Studies on cancer cell lines induced with gml, a novel gene, have demonstrated a marked increase in sensitivity to paclitaxel via apoptosis. An assay for gml expression could serve as a clinically useful predictor of chemotherapeutic sensitivity.12

Clinical Applications

Clinical Applications

Paclitaxel has demonstrated a broad spectrum of antitumor activity. Phase I trials, begun in 1983, demonstrated paclitaxel`s antineoplastic activity against several tumor types, such as the following13–20:

• Adenocarcinoma of unknown origin

• Refractory ovarian carcinoma

• Small cell and non–small cell lung carcinoma

• Gastric, colon, prostate, breast, and head and neck carcinomas

In early studies, impressive results were seen using paclitaxel in combination with other antineoplastic agents, such as cisplatin.21 Having treated patients who were previously resistant to cisplatin with the combination of cisplatin and paclitaxel, the Gynecology Oncology Group reported a 33% response rate.22 Trials were quickly conducted on a number of solid tumor types, including small cell and non–small cell lung, renal, gastric, breast, advanced ovarian, colon, and cervical carcinomas; head and neck cancers; small cell lung and prostate carcinomas; and low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.23 Paclitaxel also has activity in other malignancies that are refractory to conventional chemotherapy, including previously treated lymphoma, small cell lung cancers, and esophageal, gastric, endometrial, bladder, and germ cell tumors. Paclitaxel is also active against AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Although paclitaxel is a well-accepted treatment option for these cancers and others, significant toxicities, such as myelosuppression and peripheral neuropathy, limit the effectiveness of paclitaxel-based treatment regimens.24,25 These toxicities will be discussed further.

Toxicity

Toxicity

Human poisoning from the deliberate consumption of yew leaves or seeds is now rare. Published cases involving psychiatric patients and prisoners describe the first symptoms of intoxication as appearing 1 hour after ingestion. The manifestations include mydriasis, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and arrhythmia. Death occurs from cardiac arrest 3 to 24 hours after ingestion.26 The lethal dose in humans is approximately four or five handfuls of leaves, corresponding to 150 needles. No specific antidote is known.

Paclitaxel binds 95% to 98% with plasma proteins yet is readily eliminated through hepatic metabolism, biliary excretion, and/or extensive tissue binding. Total urinary excretion has been insignificant, indicating that renal clearance contributes minimally to systemic clearance.20,27–29 Hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450 (CYP) is involved for both paclitaxel and docetaxel. However, the former is hydroxylated by CYP2C8, whereas the latter is hydroxylated by CYP3A4.30

Toxicity manifests as follows:

Junctional tachycardia via conduction block rather than direct primary toxicity on myocytes has been suggested.31 Hypersensitivity, skin reactions, and accumulated fluid retention syndrome are minimized with a 3- to 5-day regimen of corticosteroids prior to paclitaxel infusion.32

Patients with leukemia who are treated with high doses of paclitaxel exhibited mucositis, which has also appeared in response to lower, cumulative dosing. An accumulation of epidermal cells with abnormal paclitaxel-induced spindle asters has been evident in ulcerated mucosa, indicating that the cell cycle was arrested in mitosis.33

Paclitaxel has been known to inhibit neurite growth and induce prominent morphologic effects, such as microtubule bundles in neurons, satellite cells, and Schwann cells in organotypic dorsal root ganglion cultures.34–39 Clinically, the most common symptoms have been glove-and-stocking paresthesias and perioral numbness. Distal sensory loss to large-fiber (proprioception, vibration) and small-fiber (pinprick, temperature) modalities and loss or decrease of distal deep tendon reflexes have been noted, although motor nerves seem to be spared. In general, the clinical incidence and severity of peripheral neurotoxicity have been dose-related. Patients with a history of substantial alcohol use have appeared to be more predisposed to the development of the neurosensory toxic effects of cisplatin and paclitaxel.13–16,40–42

The development of a suitable clinical formulation has been hampered by paclitaxel`s poor aqueous solubility. Cremophor is being used as the vehicle for administration and has been implicated in side effects, such as type 1 hypersensitivity reactions.43

Neutropenia, the principal dose-limiting toxic effect of paclitaxel, resolves rapidly (in 15 to 21 days) after treatment is stopped.40 The major clinical risk factor for neutropenia seems to be the extent of prior myelotoxic chemotherapy and/or irradiation.

Bradyarrhythmias, which have been noted as transient and asymptomatic, have been reported during paclitaxel infusion in at least 29% of patients with ovarian cancer.40 This development appears to be related more to paclitaxel, because other agents formulated with Cremophor have not been associated with similar arrhythmias. Atypical chest pains during paclitaxel infusion have been observed, but they are believed to be a manifestation of a hypersensitivity reaction.26,41

Other paclitaxel- or Cremophor-related side effects are sudden and complete alopecia, often occurring in a single day; local venous toxic effects such as erythema, tenderness, and cellulitis in areas of dermal extravasation; as well as fatigue, headaches, taste perversions, significant elevations in serum triglycerides, and minor rises in hepatic and renal function values.20

Additional precautions may be necessary with the concurrent use of the medications listed in Box 128-1.

BOX 128-1 Medications That Interact with Paclitaxel

• Amphotericin B by injection (e.g., Fungizone)

• Chloramphenicol (e.g., Chloromycetin)

• Ganciclovir (e.g., Cytovene)

• Interferon (e.g., Intron A, Roferon A)

Data from U.S. Pharmacopeia. Drug interactions, vol. II. Rockville, MD: United States Pharmacopeial Convention, 1997:1237-1238.

Medical problems that may affect the use of paclitaxel are listed in Box 128-2. Studies in rats and rabbits have shown that paclitaxel causes miscarriages and fetal deaths. Breastfeeding is contraindicated during paclitaxel therapy. Paclitaxel bound to albumin rather than using a solvent results in fewer and less severe side effects, with much reduced allergic reactions.44

1. Bolsinger C., Jaramillo A.E. Taxus brevifolia Nutt. Pacific Yew, 1990. In: Burns R.M., Honkala B.H. Silvics of forest trees of North America. (rev ed). Portland, OR: Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service; 1990:17.

2. Hartzell H., Jr. The yew tree: a thousand whispers. Eugene, OR: Hulogosi; 1991. 31, 80, 154-156, 176, 230

3. Rowinsky E.K., Donehower R.C. Taxol: twenty years later, the story unfolds. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1778–1781.

3a. Cragg G.M. Paclitaxel (Taxol): a success story with valuable lessons for natural product drug discovery and development. Med Res Rev. 1998 Sep;18(5):315–331.

4. Duke J. Handbook of northeastern Indian medicinal plants. Lincoln, MA: Quarterman; 1986. 156

5. Cunningham S. Encyclopedia of magical herbs. St. Paul, MO: Llewellyn Publications; 1985. 228

6. Wehland J., Henkart M., Klausner R., et al. Role of microtubules in the distribution of the Golgi apparatus: effect of taxol and microinjected anti-alpha-tubulin antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4286–4290.

7. Rowinsky E.K., Donehower R.C., Jones R.J., et al. Microtubule changes and cytotoxicity in leukemic cell lines created with taxol. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4093–4100.

8. De Brabander M., Geuens G., Nuydens R., et al. Taxol induces the assembly of free microtubules in living cells and blocks the organizing capacity of the centrosome and kinetochores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:5608–5612.

9. Brasch R.C., Rockoff S.D., Kuhn C., et al. Contrast media as histamine liberators. II. Histamine release into venous plasma during intravenous urography in man. Invest Radiol. 1970;5:510–513.

10. Shedadi W.H. Adverse reactions to intravenous administration of contrast media: a comparative study based on a prospective study. Am J Roentgenol. 1975;124:145–151.

11. Lanni J.S., Lowe S.W., Licitra E.J., et al. p53-independent apoptosis induced by paclitaxel through an indirect mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9679–9683.

12. Kimura Y., Furuhata T., Shiratsuchi T., et al. GML sensitizes cancer cells to taxol by induction of apoptosis. Oncogene. 1997;15:1369–1374.

13. Koeller J., Brown T., Havlin K., et al. A phase I/pharmacokinetic study of taxol given by prolonged infusion without premedication. Proc ASCO. 1989;8:82.

14. Donehower R.C., Rowinsky E.K., Grochow L.B., et al. Phase I trial of taxol in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1987;71:1171–1177.

15. Wiernik P.H., Schwartz E.L., Strauman J.J., et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of taxol. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2486–2493.

16. Wiernik P.H., Schwartz E.L., Einzig A., et al. Phase I trial of taxol given as a 24-hour infusion every 21 days: responses observed in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1232–1239.

17. Legha S.S., Tenney D.M., Krakoff I.R. Phase I study of taxol using a 5-day intermittent schedule. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:762–766.

18. Grem J.L., Tutsch K.D., Simon K.J., et al. Phase I study of taxol administered as a short i.v. infusion daily for 5 days. Cancer Treat Rep. 1987;71:1179–1184.

19. Ohnuma T., Zimet A.S., Coffey V.A., et al. Phase I study of taxol in a 24-hour infusion schedule. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1985;26:662.

20. Kris M.G., O’Connell J.P., Gralla R.J., et al. Phase I trial of taxol given as a 3-hour infusion every 21 days. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70:605–607.

21. Belani C., TAX 326 Study Group. Phase III randomized trial of docetaxel in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin or vinorelbine plus cisplatin in advanced non–small cell lung cancer: interim analysis. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(3 suppl 9):10–14.

22. Thigpen J.T., Blessing J.A., Ball H., et al. Phase II trial of taxol as second-line therapy for ovarian carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1990;9:604.

23. Rowinsky E.K. Paclitaxel pharmacology and other tumor types. Semin Oncol. 24(6 suppl 19), 1997 Dec. S19-1-S19-12

24. Marupudi N.I., Han J.E., Li K.W., et al. Paclitaxel: a review of adverse toxicities and novel delivery strategies. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007 Sep;6(5):609–621. Review

25. Mekhail T.M., Markman M. Paclitaxel in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002 Jun;3(6):755–766.

26. Appendino G. Taxol (paclitaxel): historical and ecological aspects. Fitoterapia. 1993;64:5–25.

27. Jacrot M., Riondel J., Picot F., et al. Action of taxol on human tumors transplanted in athymic mice. C R Seances Acad Sci III. 1983;297:597–600.

28. Riondel J., Jacrot M., Nissou M.F., et al. Antineoplastic activity of two taxol derivatives on an ovarian tumor xenografted into nude mice. Anticancer Res. 1988;8:387–390.

29. Sternberg C.N., Sordillo P.P., Cheng E., et al. Evaluation of new anticancer agents against human pancreatic carcinomas in nude mice. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10:219–221.

30 Dorr R.T. Pharmacology of the taxanes. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:S96–S104.

31. Faivre S., Goldwasser F., Soulie P., et al. Paclitaxel (Taxol)-associated junctional tachycardia. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:714–716.

32. Von Hoff D.D. The taxoids: same roots, different drugs. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:S3–S10.

33. Hruban R.H., Yardley J.H., Donehower R.C., et al. Taxol toxicity: epithelial necrosis in the gastrointestinal tract associated with polymerized microtubule accumulation and mitotic arrest. Cancer. 1989;63:1944–1950.

34. Masurovsky E.B., Peterson E.R., Crain S.M., et al. Microtubule arrays in taxol-treated mouse dorsal root ganglion-spinal cord cultures. Brain Res. 1981;217:392–398.

35. Masurovsky E.B., Peterson E.R., Crain S.M., et al. Morphological alterations in satellite and Schwann after exposure of fetal mouse dorsal root ganglia-spinal cord culture to taxol. IRCS Med Sci Libr Compend. 1981;9:968–969.

36. Masurovsky E.B., Peterson E.R., Crain S.M., et al. Morphological alterations in dorsal root ganglion neurons and supporting cells of organotypic mouse spinal cord-ganglion cultures exposed to taxol. Neuroscience. 1983;10:491–509.

37. Letourneau P.C., Ressler A.H. Inhibition of neurite initiation and growth by taxol. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1355–1362.

38. Letourneau P.C., Shattuck T.A., Ressler A.H. Branching of sensory and sympathetic neuritis in vitro is inhibited by treatment with taxol. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1912–1917.

39. Roytta M., Horwitz S.B., Raine C.S. Taxol-induced neuropathy: short-term effects of local injection. J Neurocytol. 1984;13:685–701.

40. McGuire W.P., Rowinsky E.K., Rosenshein N.B., et al. Taxol: a unique antineoplastic agent with significant activity in advanced ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:273–279.

41. Rowinsky E.K., Burke P.J., Karp J.E., et al. Phase I and pharmacodynamic study of taxol in refractory acute leukemias. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4640–4647.

42. Burgoyne R.D., Cumming R. Taxol stabilizes synaptosomal microtubules without inhibiting acetylcholine release. Brain Res. 1983;280:190–193.

43. Laussus M., Scott D., Leyland-Jones B. Allergic reactions (ar) associated cremophor (c) containing antineoplastic (anp). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1985;4:1042.

44. Montana M., Ducros C., Verhaeghe P., et al. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: the benefit of this new formulation in the treatment of various cancers. J Chemother. 2011 Apr;23(2):59–66.