Tactical Emergency Medical Support and Urban Search and Rescue

Tactical Emergency Medical Support

Law enforcement agencies in the 21st century face an increase in terrorist threats and new challenges, including organized opposing forces, military-type weapons, direct fire, hostage and barricade situations, and potential toxic hazards. As these threats have increased, so has the recognition of the need for integrated medical support of tactical operations.1 Tactical emergency medical support (TEMS) is the specialty of emergency medical services (EMS) established to maintain safety, health, and welfare for combat medical units and special operations civilian law enforcement units, such as special weapons and tactics (SWAT) teams, hostage rescue teams, and special emergency rescue teams.1 These specially trained teams are composed of highly trained and specially equipped personnel who are tasked with mitigating and responding to many different high-risk situations.2–5 Events such as the World Trade Center bombings and hurricane Katrina have demonstrated the need for many nonhospital health care personnel to use some of these current military out-of-hospital medical strategies.

Tactical Medical History

In the civilian setting, snipers, mass demonstrations, riots, and fire bombings gained notoriety as new forms of urban conflict in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s, which led to the formation of the first SWAT unit. In 1996, there were more than 5000 SWAT teams in the United States supporting local, state, and federal agencies. Essentially today, more than 90% of municipalities with a population greater than 50,000 have a SWAT team.5 With the evolution of these specialized law enforcement tactical teams, the need for military-style EMS support began to emerge.

Because of the dangerous environment, SWAT team members are at high risk for injury, with a casualty rate of 33 injuries per 1000 officer missions. Suspects are injured at the rate of 18.9 injuries per 1000 officer missions, and bystanders are injured at the rate of 3.2 per 1000 officer missions. It was recognized that traditional EMS providers were not properly trained or equipped to enter these unique and sometimes remote austere environments to care for casualties. In fact, basic EMS training still emphasizes that personnel should wait until the “scene is safe” before rendering medical care to patients. Past incidents, such as shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, Ruby Ridge in Idaho, the University of Texas in Austin, and the Mormon Library in Salt Lake City, proved that sequestering of medical personnel far from the area of operations leads to delays in definitive trauma care, with potentially higher morbidity and mortality.6 The tactical environment necessitates that the medical provider possess a unique training and skill subset to use a different set of field assessment and treatment priorities and strategies for monitoring and sustaining health maintenance. Provision of tactical medical care has now become an integral part of preplanning for federal, state, and local tactical teams in response from lessons learned.1,2

The principles of tactical combat casualty care (TCCC) have been refined and now applied on today’s battlefield7–10 as well as in most civilian TEMS teams.1,11–13 TCCC is a set of guidelines that aim to prevent further casualties, to accomplish the tactical mission, to save the maximum number of lives, and to minimize morbidity of the injured. These guidelines are developed by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care, which falls under the U.S. Defense Health Board. The TCCC guidelines are based on treatment of the leading preventable causes of combat death, which include hemorrhage from a compressible site, tension pneumothorax, and airway compromise.11–13 In the most recent TCCC guidelines, attention to hypothermia prevention, intravenous access, improved en route care, closed head injury, and pain management techniques are also addressed.11 Whereas TCCC is widely accepted in the military combat setting and has largely been extrapolated to the civilian environment, there are some data that question the applicability of TCCC to the civilian environment.12

Goals of Tactical Emergency Medical Support

In the early years of development, TEMS focus was on care and evacuation of wounded. This role has now evolved to include more emphasis on mission planning, primary care, preventive medicine, and emergency care of illness and injury. Although the primary goal of TEMS is to enhance the law enforcement mission, the tactical medical role involves a continuum of care that includes maintenance of team health; reconnaissance of environmental and situational aspects of the mission; coordination of local emergency medical support; creation of evacuation plan and routes; and assessment of future medical needs of the team, perpetrators, bystanders, and possible hostages.1,14 Implementation of an effective tactical medical support program is directed at achievement of several important goals (Box 192-1).

Tactical Team Structure, Training, and Integrated Medical Support

SWAT team and combat TEMS structure and size vary throughout the United States according to location and purpose. The typical team is composed of assault teams, which make initial contact with suspects, and arrest teams, which support the assault team. There are also rescue teams, backup teams, and hostage and negotiation teams. A unit commander supervises the operation from a command post.2

The TEMS component of a tactical unit, like team structure, varies widely throughout the United States. Some SWAT teams use “standby” EMS personnel, whereas others have physician-only TEMS providers. Much like the military Special Forces, many civilian tactical law enforcement agencies are now integrating medical support into the tactical team to enhance mission success.2

Law enforcement agencies using integrated medical support have varying medical qualifications. The use of an emergency medical technician for medical coverage has the advantage of availability and modest cost. Medical directors may be able to train basic providers with an enhanced skill set to provide appropriate medical care for tactical support. However, the increased skill set possessed by advanced nonhospital providers makes them favorable in a TEMS environment.2,11 In a small number of jurisdictions, emergency physicians and residents provide medical oversight for TEMS units and are also deployed as medical operators in the tactical environment.2,4 Although physician providers offer a broader scope of practice and do not require direct medical control, they usually have limited out-of-hospital experience and also require tactical training. In addition, as the law enforcement mission takes on additional roles overseas, there is a growing need for forward surgical teams similar to military forward surgical teams that can function in remote areas. The Georgia Health Sciences University has developed one such surgical resuscitation team that has been deployed in support of law enforcement operations (www.georgiahealth.edu/ems/COM/Tactical/).

Training Issues

The tactical environment is different from the traditional EMS environment. Traditional EMS doctrine taught personnel to ensure that the scene is “safe” before attempting to render care.11 This principle is not possible in some tactical situations. Tactical training needs to take into account team tactics and movement; cover and concealment; equipment issues; nuclear, biologic, and chemical training; rappelling; weapons familiarity; and noise and light discipline training.2 Also, routine training needs to be done in basic rescue tactics, tactical room entries, open area rescues and tactics, movement under fire, cover and concealment, officer down drills, and, in some systems, firearm training (Fig. 192-1). Furthermore, many teams are now training all team members in medical management for lifesaving interventions.

In the military and operational environments, there is a significant increase in the number of penetrating traumatic injuries (e.g., gunshot, fragmentary, and blast propellant wounds).13–15 Because of the increased complexity and number of combat casualties and the possibility that civilian TEMS providers may be exposed to such, additional training and knowledge of the TCCC guidelines are important for the operational and tactical medic. Although advanced trauma life support may be applicable to the emergency department management of trauma patients in both civilian and military hospitals, it was not created for combat or tactical out-of-hospital medicine.11,16 The three goals of TCCC are to treat the casualty, to prevent additional casualties, and to complete the mission.6 TCCC is divided into three distinct phases to provide the correct medical interventions at the correct time in the continuum of out-of-hospital care (Box 192-2).

Care under Fire.: In terms of medical delivery in the civilian tactical environment, the area is usually divided into three zones—cold, warm, and hot. These zones are based on tactical environment, threat level, and treatment options, which are based on a risk-benefit ratio relative to the medical provider and patient. The cold zone is a safe environment with no threat to injury. This zone is outside the inner perimeter, and regular EMS treatment principles usually apply. In the warm zone, threat is not considered immediate but still exists. Finally, the hot zone is characterized by possible direct exposure to hostile fire.

As such, care under fire refers to care being rendered in the hot zone. In this zone, the medic and casualty are under direct effective hostile fire. Care in this phase is limited but not nonexistent. When care may be rendered, airway management, the first medical priority in routine out-of-hospital medicine, is best deferred until the tactical field care phase because of difficulty in maintaining the airway during evacuation under direct fire. Also, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cervical spine immobilization have little or no role in the treatment of penetrating injuries in this phase and are not a priority in the combat environment.16–18 Recommended care is limited to mitigation of threat (i.e., suppressive fire), placement of the casualty in rescue position if possible, tourniquet use, and evacuation of the casualty to a safer “zone” or “phase” of care if possible.

Because uncontrolled extremity hemorrhage was the leading cause of preventable battlefield death, a large portion of research and training was directed toward hemorrhage control.13,19 During the current conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, newer tourniquets, hemostatic agents, and dressings and intravenous therapies have been developed, researched, and fielded by the military with unprecedented speed, reducing morbidity and mortality for compressible, extremity hemorrhage.19 During the care under fire phase, extremity hemorrhage control is ideally gained through the use of tourniquets. Although shunned for many years, tourniquets have re-emerged as the standard of care in this environment because of low complication rates, ease of use, rapid application, and effectiveness in stopping blood loss.6,19–24 Improvised tourniquets such as rubber surgical tubing are not recommended and should not be used unless commercial tourniquets are unavailable.23 Several studies have found that tourniquet use on the current battlefield has not resulted in increased limb loss or permanent disability even among patients thought to have had tourniquets applied unnecessarily and has resulted in a reduction in mortality with application before onset of shock and in the prehospital environment.6,19,21

Many types of extremity tourniquets are presently available for both civilian and military use. Two tourniquets currently used on today’s battlefield by the U.S. Army are the Combat Application Tourniquet (C-A-T) and the Special Operations Forces Tactical Tourniquet (SOFT-T).19,24 On the basis of current literature, both the U.S. and the Israeli military, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and civilian agencies in the United States have embraced tourniquets as an initial hemorrhage control option during the care under fire phase as well as for uncontrolled extremity hemorrhage to achieve rapid control of bleeding.11,21 The current TCCC recommendation is for liberal use of appropriate tourniquets for uncontrolled extremity hemorrhage in the tactical environment.

Tactical Field Care.: The second phase of care, tactical field care, is medical treatment rendered in the warm zone. This phase consists of medical care that is delivered while the medic and casualty are still under threat of injury but not under direct, effective hostile fire. Simply by dragging a casualty 5 feet around the corner of a building could transition the medic from care under fire to tactical field care. Care in this phase focuses on several areas that have been shown to increase morbidity and mortality in tactical environments if they are not addressed.17 Airway establishment and maintenance are first addressed in this phase of treatment. Next, breathing issues, such as tension pneumothorax and open pneumothorax (sucking chest wound), may need to be addressed in this phase of care. Circulatory issues, such as tourniquet replacement with direct pressure dressings or advanced hemostatic agents and fluid therapy, are then addressed. Intravenous or interosseous access needs to be established. Hypothermia prevention, adequate analgesia, prophylactic antibiotics, and appropriate use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation are also addressed in this phase.13

Advanced Hemostatic Agents.: The ideal out-of-hospital hemostatic agent ideally would require little training; be nonperishable, durable, flexible, and inexpensive; adhere to the wound only; pose no direct risk of disease; not induce a tissue reaction; and effectively control hemorrhage from arterial, venous, and soft tissue bleeding. There is no single ideal advanced hemostatic agent that currently meets all of these criteria for either military or civilian use. However, many hemostatic agents have been used successfully for uncontrolled hemorrhage on today’s battlefield and have contributed to reduced morbidity and mortality in penetrating combat trauma.25–30

Although many hemostatic agents are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and have been used in both the civilian and military environments, the agent currently recommended by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care is Combat Gauze. Combat Gauze, a mineral-based dressing containing a kaolin coating, is thought to function by activation of clotting factors. More recent dressings with fine-mesh poly-rayon gauze and chitosan impregnation have been demonstrated to be at least as efficacious as Combat Gauze in a porcine model.29

Point Compression Devices and Trunk Tourniquets.: The rapid development and fielding of tourniquets and hemostatic agents on today’s battlefield have greatly reduced morbidity and mortality from previously uncontrolled hemorrhage, particularly from isolated extremity injuries. However, exsanguination-related mortality still exists. Anatomic areas that are not amenable to tourniquet application, referred to as junctional areas (i.e., neck, groin, axilla), have now become the focus of hemostatic research.31 In fact, the current combat epidemiology reports that junctional injury and bleeding is now the most common “potentially survivable” combat injury. Because junctional injuries continue to be a challenge to hemorrhage control in the tactical setting, newer devices are being developed to control these injuries in the field setting to allow the casualty time to have surgical control in an operative setting.30–32 One of the newer devices has been approved by the FDA for control of proximal femoral artery injuries, the Combat Ready Clamp (CRoC, Combat Medical Systems). This is a large C-clamp that is placed over the femoral vessels to provide direct compression. Another device under development is the abdominal aortic tourniquet, which is a pneumatic tourniquet that externally compresses and occludes the abdominal aorta at its bifurcation. This device has been shown to occlude the abdominal aorta in a pig model for up to 60 minutes without evidence of bowel ischemia or hyperkalemia and is pending FDA approval for the indication of hemorrhage control of proximal femoral and pelvic vascular injuries.33

Tension Pneumothorax.: Another leading cause of potentially preventable battlefield death is tension pneumothorax, accounting for up to 3 or 4% of all fatal injuries.14,34 McPherson and colleagues34 studied radiologic and autopsy examinations of 978 fatalities from the Vietnam conflict; 15 of the casualties with identified tension pneumothorax lived long enough to be treated by a medic, but none underwent needle decompression and all of them died.

Although needle thoracostomy is a controversial procedure in the civilian trauma setting for adults, current TCCC guidelines recommend consideration of needle decompression in casualties with chest trauma and progressing respiratory distress.17,34 The current recommendation is to use a 14-gauge or larger 3.25-inch needle. This recommendation is based on computed tomography evaluation of the chest wall, which indicted that a standard 2.0-inch needle would penetrate the pleural space in only 75% of causalities.35

Airway Management.: Airway compromise is also a potentially preventable cause of battlefield death.36 Historically, airway compromise is responsible for approximately 1% of fatal injuries on the battlefield and is due to facial or neck trauma causing obstruction. These data are consistent with a more recent review of fatal airway injuries from Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, which demonstrated an airway fatality rate of 1.8%, with 100% having penetrating injuries to the face or neck.36

Initially, in an unconscious patient with intact upper airway anatomy at risk for airway compromise, the recovery position and minimally invasive adjuncts, such as the nasopharyngeal airway and the oropharyngeal airway, are emphasized. However, given the high incidence of trauma as a cause of airway obstruction, the cricothyroidotomy is taught as the definitive airway management technique on the battlefield if simple maneuvers fail. Traditional methods providing ventilation, such as endotracheal intubation, the laryngeal mask airway, the Combitube, and the King laryngeal tube airway, may not be as feasible in tactical situations. The initial training requirements as well as maintenance issues for these skills for all military medics are simply not practical. Furthermore, use of white light required for laryngoscopy may draw enemy fire on the battlefield. Finally, on the basis of the best available data, many patients needing airway management are likely to have disrupted upper airway anatomy, for which these skills would not be successful and cricothyroidotomy would be indicated. A recent review of battlefield fatalities demonstrated a high failure rate of cricothyroidotomy (5/5) and raises the question of the most appropriate algorithm for airway management in the tactical setting.36

Intravenous Access and Fluid Resuscitation.: The tactical environment often makes intravenous access difficult, and alternative techniques and routes may be needed to establish access.17,37–39 Medics therefore are trained to obtain intraosseous access for fluid administration if intravenous access is not obtainable or timely. Several newer intraosseous devices are used in both civilian and combat tactical environments, including the EZ-IO, the Pyng FAST1 sternal intraosseous infusion device, and the Bone Injection Gun, with great success and little morbidity.40,41

The current recommendations for intravenous resuscitation on the battlefield focus only on those patients with signs of hemorrhagic shock. Because the majority of combat casualties present with non–life-threatening penetrating extremity injuries, the number of casualties actually requiring intravenous fluids in the field is few. In fact, fluids are encouraged to be taken orally if the casualty is conscious and can tolerate drinking.17 If fluids are necessary, TCCC guidelines recommend an infusion of 500 mL of Hextend, followed by an additional 500 mL in 30 minutes if shock is still present.17,31

Hextend, a colloid, is the recommended fluid of choice over crystalloid solutions. Hextend remains in the intravascular space longer, requiring significantly less volume than crystalloids. These factors are critical when supplies must be carried in the medic’s pack. Future battlefield resuscitation strategies may include hypertonic saline or combinations of hypertonic solutions and colloids. A growing scientific literature supports this “hypotensive resuscitation” strategy.31,42,43

Hypothermia Management.: Hypothermia has been well recognized as an independent factor contributing to increased morbidity and mortality in trauma patients. Studies have shown hypothermia to be associated with increases in acidosis, coagulopathy, multiple organ failure, length of hospital stay, and mortality.44,45 In the austere environment, prolonged out-of-hospital times, cold fluid administration, and environmental factors affect the patient’s core temperature, as does bleeding that results in hypoperfusion, which alters the body’s thermoregulation and results in hypothermia.

TCCC emphasizes prevention of hypothermia (<34° C) in patients with penetrating trauma. Prevention of heat loss should start as soon as possible after wounding. This is optimally accomplished in a layered manner. Several new devices are being tested and fielded in the combat out-of-hospital setting for hypothermia prevention to maintain casualty core temperature as well as to administer warmed fluids.46

Analgesia.: The tactical environment exacerbates the typical challenges found in treatment of acute pain and has the additional obstacles of a lack of supplies and equipment, delayed or prolonged evacuation times and distances, devastating injuries, provider inexperience, and dangerous tactical situations.47,48 Studies have shown an increase in the incidence of chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with failure to recognize and to treat acute pain appropriately as well as a reduction in PTSD incidence when pain is adequately managed, particularly with early use of ketamine.49,50

Finally, other newer analgesic agents and routes of delivery are being used on the battlefield. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate has been found to relieve moderate to severe pain on the battlefield and is currently carried by many Special Forces medics.51 Also, ketamine has been used successfully as an out-of-hospital analgesic in the civilian and combat setting.52 Ketamine in subanesthetic doses is an almost ideal analgesic because of its profound pain relief, its role in prevention of opioid hyperanalgesia, and its large margin of safety.53

Triage and Advanced Vital Signs.: It has been hypothesized that some trauma deaths may be preventable if the severity of blood loss can be recognized earlier during out-of-hospital medical care. It is obviously better to prevent hemodynamic compromise (i.e., shock) than to treat it once it has already begun to occur.

In an attempt to provide new possibilities for more efficient algorithms that may assist in determination of treatment and evacuation priorities for patients with unrecognized hypovolemia and early shock, new and more accurate noninvasive indicators of the underlying physiologic status in trauma patients who have initial normal systolic blood pressure and Glasgow Coma Scale scores have been investigated and implemented in current combat operations.54,55 Some of these indicators of hypovolemia include derived physiologic variables (e.g., shock index, pulse pressure, and field trauma score)55–57 and continuous “real-time” variables (e.g., electrocardiogram R wave amplitude and heart rate variability).58,59 The National Association of EMS Physicians, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has led an effort to standardize mass casualty triage. Through this project, a new triage system has been developed that uses the principles of TCCC. This system is called SALT (sort, assess, lifesaving interventions, and treatment or transport) and has been endorsed by multiple organizations, including the American College of Emergency Physicians.60

Combat Casualty Evacuation Care.: Combat casualty evacuation care is the third phase of care. It is rendered to the casualty in the cold zone and while the casualty is evacuated to definitive medical care. Care now begins to closely approximate traditional civilian field medical care and includes advanced life support en route to the receiving facility, often a trauma center (Fig. 192-2).11

Intravenous Hemostatic Agents.: In the future, optimal out-of-hospital hemorrhage control in the combat environment may also involve use of intravenous agents for replacement and coagulation principles. In selected combat nonhospital settings, tranexamic acid, hemoglobin substitutes, lyophilized plasma, freeze-dried blood, and component products are currently being developed or evaluated for appropriate use.42,61 In this phase of care, on the basis of recent literature, the TCCC currently recommends that tranexamic acid be administered as 1 g in 100 mL of normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution as soon as possible, but not later than 3 hours after injury, if the casualty has major hemorrhage or is probably going to require a significant transfusion.61,62

TEMS Environment

Practicing effective medical care in the tactical environment requires TEMS personnel to be well educated, trained, and equipped. Integrated “team” training allows the medical support members to understand their roles and to learn all aspects of tactical law enforcement operations and fundamentals on how to approach the tactical medical arena. TEMS competency-based guidelines have recently been published to guide the development of TEMS training curricula.1 A project has been initiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop a nationally standardized curriculum for tactical medicine training. This project, using an expert panel and review of the scientific literature, refined the previously published outcome competencies and developed terminal and enabling training objectives to the competencies. The results of this project will be published as a national TEMS curriculum. In addition, training curricula have been established, such as the National Tactical Officers Association’s Specialized Tactics for Operational Rescue and Medicine (STORM) for medics, operators, medical directors, and team commanders. These courses are based on the national TEMS curriculum and use the trainer methodology.

Hazardous Materials

Incidents involving clandestine drug laboratories and weapons of mass destruction are also considerations in a TEMS environment. Rapid decontamination must be taught and practiced by tactical teams because adequate decontamination is usually not available in the inner perimeter.63

Forensic Science

Basic knowledge of forensic science is important for recognition and preservation of evidentiary items. Documentation of wound and blood patterns should be done. All evidence should be collected appropriately and the chain of custody maintained.64

Medical Threat Assessment

Medical threat assessment (MTA) is an important part of medical planning and should be integrated into the tactical operation.2 The MTA considers the potential medical threats that may confront the team during the tactical operations and develops the plan to mitigate and to respond to the threats. Once the MTA is complete, a plan is then developed on the basis of the medical intelligence to address each possible situation, with the realization that the plan may change as the mission evolves.

Urban Search and Rescue

Perspective

Urban search and rescue (US&R) is the science of responding to, locating, reaching, medically treating, and safely extricating victims entrapped by collapsed structures. US&R is a “multihazard” discipline because it may be needed in a variety of emergencies and disasters, including wilderness mishaps, natural disasters such as the recent earthquakes in Haiti and Japan, and man-made disasters (e.g., terrorist attacks, building and structure collapse, hazardous materials spills).65,66 Federal activation of US&R teams occurs when local and state resources have been overwhelmed and there has been a request from a state governor to the President for the activation of federal response assets. In addition, in catastrophic events, the activation of military assets may be required to assist in a support role of other local, state, and federal assets.66,67 For responding resources to be effective, they should be highly trained, quickly deployable, mobile, and self-sufficient.

Components and Structure of an Urban Search and Rescue Team

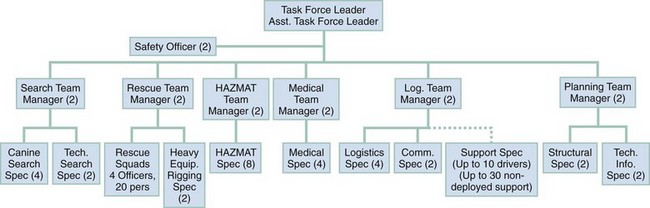

The responding team must mobilize quickly to accomplish its objectives and should not place additional demands on the already stressed infrastructure. Figure 192-3 shows the organizational structure of a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) US&R team.66 There are 28 FEMA US&R task forces throughout the continental United States that are trained and equipped to handle structural collapse. FEMA will deploy the three closest task forces within 6 hours of notification of an emergency. Each task force consists of two 31-person teams, four canines, and a comprehensive equipment cache. US&R task force members work in four areas of specialization: search, to find victims trapped after a disaster; rescue, which includes safely digging victims out of tons of collapsed concrete and metal; technical, made up of structural specialists who make rescues safe for the rescuers; and medical, which cares for the victims before and after a rescue.

Figure 192-3 Structure of a FEMA US&R team.

An effective US&R team needs both properly trained personnel and appropriate equipment. The equipment cache should allow the task force to be totally self-sufficient for the first 72 hours and to be capable of 24-hour operation for 10 days.65,67 The FEMA equipment cache is divided into five groups: rescue equipment, medical equipment, technical equipment, communications equipment, and logistics equipment. The medical equipment cache was designed to treat the unique medical needs of trapped victims as well as the medical needs of the team. The medical cache contains enough supplies to handle 10 critical cases, 15 moderate cases, and 25 minor cases. The cost of the entire cache is approximately $2 million.66,67

Coordination and cooperation with local resources and other teams are critical.68 The US&R team is integrated into the Incident Command System at the disaster.

The technical team is composed of various specialists, including structural specialists, hazardous materials specialists, heavy rigging and equipment specialists, technical information specialists, and communications specialists.68 These specialists work collaboratively to ensure a safe and efficient operation.

The logistics team is responsible for all the equipment needs, including inventory, issuing, and record keeping.68

Finally, the medical component is composed of medical personnel who are responsible for the medical needs of both the task force personnel and the victims. Typically, the medical personnel are emergency physicians and paramedics.68,69

Medical Team Operations in Urban Search and Rescue

A number of unique considerations must be addressed for US&R. As with TEMS, team physicians must realize that they will be operating outside of their usual environment and that they are not in charge overall. Typically, the physician on the team works with the team leader and the managers of the other components. To do this efficiently, the physician should be familiar with the capabilities and training of all the members on the team and the Incident Command System. Cross-training of team members is ideal.68–70

Medical Team Tasks

Predeployment.: The job of the medical team in the predeployment phase is to ensure that the entire team is fit and functional for deployment and that the medical equipment cache is organized and up-to-date.69 The perceived medical threats in the deployed area must also be addressed (e.g., endemic disease, water contamination, insect threats, existing medical support). A family and communication support system should also be set up before the deployment.

Deployment.: The medical team is responsible for much more than just treatment of the victims. Medical intelligence information needs to be collected and addressed (Box 192-3). A plan is required for transfer and transport of victims and for fatality management.

The medical action plan is critical for ensuring smooth operations and should be updated as conditions or knowledge changes.66,68,69 The medical component of a US&R team needs to be able to provide care for its own team members, whose needs may exceed those of the victims. The medical team also needs to assess the adequacy of team members’ rest and sleep and the psychological effects of the situation.68,69 In addition, the US&R medical assets must be integrated with the overall medical response that is guided under Emergency Support Function #8, Public Health and Medical Services. This includes integration with existing medical resources, disaster medical assistance teams, TEMS resources, military resources, and public health. If there is a canine search component, the medical team should receive some sort of basic veterinary training before deployment.68,69

Confined Space Issues

A confined space is defined as any space with limited access and ventilation. The physician and medical team must be prepared to work in this setting during a deployment and should be aware of issues related to team and victim safety, air purification, and structural dynamics related to collapse or impending collapse.68–70 Medical providers may be asked for input on ceasing of rescue operations based on the likelihood of finding survivors. Evidence from the 2010 Haitian earthquake indicates that this decision should be based on the individual characteristics of the event and should not rely on predefined time frames to determine ceasing of search and rescue operations.71

Specific Disorders in Urban Search and Rescue

US&R teams will typically be responding to the aftermath of earthquakes, collapsed structures, terrorist bombings, hurricanes, and other natural and man-made disasters.68,71 Reviews of the literature have identified the types of medical problems and conditions that might be encountered.65,66,69,70 Most of the medical conditions are those encountered in the emergency department and are handled similarly. The following clinical problems occur with much greater frequency in the US&R environment: crush syndrome, compartment syndrome, particulate inhalation, hazardous materials exposures, and blast injuries.69 Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there has also been an emphasis on preparing the US&R teams for the medical response to weapons of mass destruction.

Crush Injury and Crush Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is defined as crush injury caused by swelling of tissue inside the confining fibrous sheath of a muscle compartment, which can cause further destruction of the intracompartment muscle and nerves. Compartment syndrome is discussed in Chapter 49.

Crush syndrome is defined as the systemic manifestations caused by crushed muscle tissue. This typically occurs when blood flow is restored to the crushed tissue and the toxins are released systemically. It is estimated that 3 to 20% of earthquake victims and up to 40% of survivors of multistory building collapses will have crush syndrome.72 Early hydration of the victim in the rubble before, during, and after extrication can lessen the renal effects of crush syndrome.

Pathophysiology of Crush Syndrome.: The cause of muscle injury in crush injury is not fully understood and controversial. The intracellular contents of the cell include lactic acid, potassium, myoglobin, uric acid, enzymes, leukotrienes, thromboxane, phosphate, and others. There is also increased capillary permeability. This can lead to edema and third spacing of fluid.72 These effects occur locally until the tissue is released and reperfused. This is why victims can be trapped for days with severe crush injury and appear stable when they are reached by rescuers only to deteriorate soon after being rescued. There are reports of patients going into cardiac arrest soon after rescue.73,74 When the crushed area is released, there is a release of all the intracellular contents that have been building up locally into the systemic circulation, causing systemic symptoms. The major causes of early death due to crush syndrome are hypovolemia due to third spacing of fluid, dysrhythmias due to severe metabolic acidosis, and hyperkalemia. Delayed causes of death include renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, ischemic organ injury, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and electrolyte disturbances.72,73

Management of Crush Syndrome.: Early aggressive therapy is essential for prevention of crush syndrome, and it should begin before extrication.72–74 All victims who have an obvious crush injury or are immobilized for 4 hours or more should be considered to have crush injury. The severity of the crush syndrome may be related to the number of extremities with crush injury. In a Japanese study of earthquake victims, the incidence of acute renal failure due to crush syndrome was 50% for one involved extremity, 75% for two involved extremities, and 100% for three or more involved extremities. Once a victim is located, the medical component needs to be actively involved with the rescue process and begin treatment before extrication. Cardiovascular instability is commonly seen in crush syndrome. As extrication is being done, continuous cardiac monitoring is recommended. Adequate hydration is recommended along with the usual management of hyperkalemia (e.g., insulin or glucose, ion exchange resins, beta-agonists, and dialysis). The current guidelines taught in the FEMA medical specialists course recommend intravenous calcium only for arrhythmias that do not respond to other measures or when there is a documented severe hypocalcemia.69 It has been suggested that an average-size adult may require up to 12 L/day of fluids to sustain a forced diuresis of 8 L/day to prevent renal complications. Continued monitoring of the patient’s vital signs, hydration status, and urine output should be done to guide fluid administration until more invasive monitoring is available.70 Alkalinization of the urine to prevent renal failure has been recommended in crush syndrome but has not been subjected to proper study, and the effects of the alkalinization, if any, are impossible to separate from those of the volume fluid used. Rhabdomyolysis and its relationship to renal failure are discussed in Chapter 127.

Other Medical Problems in Urban Search and Rescue

Another unique medical problem in US&R is dust and airway contamination. During earthquakes and building collapses, a tremendous amount of dust is released into the air. During the first 48 hours of rescue efforts at the World Trade Center, 90% of the 10,116 New York City Fire Department rescue workers evaluated at the site reported an acute cough often accompanied by nasal congestion, chest tightness, or chest burning, but only three required hospitalization for respiratory symptoms (Fig. 192-4). A cough was eventually found in 1561 (29.1%) firefighters at baseline and 1186 (22.1%) at follow-up, including 559 with delayed onset.75 The victim of a collapsed structure should be assumed to have some sort of dust contamination. Evaluate the airway for any evidence of burns or hazardous materials exposure. During the extrication process, monitor the patient’s airway and be prepared for deterioration. If intubation is being considered, it is better to do it early before edema obstructs the airway, making the procedure more difficult. Medical management of the victim reached after prolonged entrapment is different from that in the typical trauma setting. The “scoop and run” approach of the trauma patient is not always appropriate or possible.

References

1. Schwartz, RB. Tactical medicine—competency-based guidelines. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:67–82.

2. Vayer, JA, Schwartz, RB. Developing a tactical emergency medical support program. Topics Emerg Med. 2003;25:282.

3. Heck, JJ, Pierluisi, G. Law enforcement special operations medical support. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2001;5:403.

4. Bozeman, WP. Tactical EMS: An emerging opportunity in graduate medical education. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:322.

5. Heck, JJ, Pierluisi, G. Law enforcement special operations medical support: NAEMSP position paper. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2001;5:403.

6. Mabry, RL, et al. United States Army Rangers in Somalia: An analysis of combat casualties on an urban battlefield. J Trauma. 2000;49:515.

7. Butler, FK. Tactical medicine training for SEAL mission commanders. Mil Med. 2001;166:625.

8. Butler FK, Greydanus D, Holcomb J: Combat Evaluation of TCCC Techniques and Equipment: 2005. USAISR Report No. 2006-01, November 2006.

9. Butler, FK, et al. Tactical combat casualty care 2007: Evolving concepts and battlefield experience. Mil Med. 2007;172(Suppl):1–19.

10. Holcomb, JB, Stansbury, LG, Champion, HR, Wade, C, Bellamy, RF. Understanding combat casualty care statistics. J Trauma. 2006;60:397–401.

11. National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. PHTLS: Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

12. Sztajnkrycer, MD. Tactical medical skill requirements for law enforcement officers: A 10-year analysis of line of duty deaths. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25:346–352.

13. Mabry, R, McManus, JG. Prehospital advances in the management of severe penetrating trauma. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(Suppl):S258–S266.

14. Holcomb, JB, et al. Causes of death in U.S. Special Operations Forces in the global war on terrorism: 2001-2004. Ann Surg. 2007;245:986.

15. Sebesta, J. Special lessons learned from Iraq. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:711.

16. Butler, FK, et al. Tactical management of urban warfare casualties in special operations. Mil Med. 2000;65:1.

17. McSwain N, ed. Military Medicine. Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 5th ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 2003.

18. Haut, ER, et al. Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: More harm than good? J Trauma. 2010;68:115–120.

19. Kragh, F, et al. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S38–S50.

20. Mabry, RL. Tourniquet use on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2006;171:352.

21. Kragh, JF, et al. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009;249:1–7.

22. Welling, D, et al. A balanced approach to tourniquet use: Lessons learned and relearned. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:106.

23. Walters, TJ, Mabry, RL. Issues related to the use of tourniquets on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2005;170:770.

24. Walters, TJ, et al. An observational study to determine the effectiveness of self-applied tourniquets in human volunteers. J Prehosp Care. 2005;9:416.

25. Pusateri, AE, et al. Advanced hemostatic dressing development program: Animal model selection criteria and results of a study of nine hemostatic dressings in a model of severe large venous hemorrhage and hepatic injury in swine. J Trauma. 2003;55:518.

26. Wedmore, I, McManus, J, Pusateri, A, Holcomb, J. A special report on the chitosan-based hemostatic dressing: Experience in current combat operations. J Trauma. 2006;60:655.

27. Kheirabadi, BS, et al. Comparison of new hemostatic granules/powders with currently deployed hemostatic products in a lethal model of extremity arterial hemorrhage in swine. J Trauma. 2009;66:316–328.

28. Kheirabadi, BS, et al. Determination of efficacy of new hemostatic dressings in a model of extremity arterial hemorrhage in swine. J Trauma. 2009;67:450–459.

29. Schwartz, RB, et al. Comparison of two packable hemostatic gauze dressings in a porcine hemorrhage model. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:477–482.

30. Kheirabadi, BS, et al. Clot-inducing minerals versus plasma protein dressing for topical treatment of external bleeding in the presence of coagulopathy. J Trauma. 2010;69:1062–1073.

31. Butler, F. Fluid resuscitation in tactical combat casualty care: Brief history and current status. J Trauma. 2011;70:S11–S12.

32. Kheirabadi, B, Evaluation of topical hemostatic agents for combat wound treatment. US Army Med Dep J. 2011;(Apr-June):25–37.

33. Greenfield, EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel abdominal tourniquet device for the control of pelvic and lower extremity hemorrhage. http://pdm.medicine.wisc.edu/Volume_24/issue_2/16wcdem.pdf5.

34. McPherson, JJ, Feigin, DS, Bellamy, RF. Prevalence of tension pneumothorax in fatally wounded combat casualties. J Trauma. 2006;60:573.

35. Givens, ML, Ayotte, K, Manifold, C. Needle thoracostomy: Implications of computed tomography chest wall thickness. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:211–213.

36. Mabry, RL, Edens, JW, Pearse, L, Kelly, JF, Harke, H. Fatal airway injuries during Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14:272–277.

37. Miller, DD, et al. Feasibility of sternal intraosseous access by emergency medical technician students. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9:73.

38. Calkins, MD, et al. Intraosseous infusion devices: A comparison for potential use in special operations. J Trauma. 2000;48:1068.

39. Dubrick, MA, Holcomb, JB. A review of intraosseous vascular access: Current status and military application. Mil Med. 2000;165:552.

40. Vojtko, M, Hanfling, D. The sternal IO and vascular access—any port in a storm. Air Med J. 2003;22:32–34.

41. Miller, L, Morissette, C. VidaPort—an advanced easy IO device. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8:110–111.

42. McSwain, NE, et al. State of the art of fluid resuscitation 2010: Prehospital and immediate transition to the hospital. J Trauma. 2011;70:S2–S10.

43. Dubick, M. Current concepts in fluid resuscitation for prehospital care of combat casualties. US Army Med Dep J. 2011;Apr-Jun:18–24.

44. Wade, CE, Salinas, J, Eastridge, BJ, McManus, JG, Holcomb, JB. Admission hypo- or hyperthermia and survival after trauma in civilian and military environments. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:35.

45. Eastridge, B, et al. Admission physiology criteria after injury on the battlefield predict medical resource utilization and patient mortality. J Trauma. 2006;61:820.

46. Allen, PB. Preventing hypothermia: Comparison of current devices used by the US Army in an in vitro warmed fluid model. J Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl 1):S154–S161.

47. Black, I, McManus, JG. Pain management in current combat operations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13:223–227.

48. Wedmore, IS, Johnson, T, Czarnik, J, Hendrix, S. Pain management in the wilderness and operational setting. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:585.

49. Otis, JD, Keane, TM, Kerns, RD. An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:397.

50. McGhee, LL. The correlation between ketamine and posttraumatic stress disorder in burned service members. J Trauma. 2008;64(Suppl):S195–S198.

51. Kotwal, RS, et al. A novel pain management strategy for combat casualty care. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:121.

52. Bredmose, PP, Lockey, DJ, Grier, G, Watts, B, Davies, G. Pre-hospital use of ketamine for analgesia and procedural sedation. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:62–64.

53. Galinski, M. Management of severe acute pain in emergency settings: Ketamine reduces morphine consumption. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:385–390.

54. Convertino, VA, et al. Use of advanced machine-learning techniques for noninvasive monitoring of hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2011;71:S25–S32.

55. Ryan, KL. Advanced technology development for remote triage applications in bleeding combat casualties. J Trauma. 2011;71:S61–S72.

56. Eastridge, B, et al. Hypotension begins at 110 mm Hg: Redefining “hypotension” with data. J Trauma. 2007;63:291.

57. Holcomb, JB, et al. Manual vital signs reliably predict need for life-saving interventions in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2005;59:821–828.

58. Cooke, WH, et al. Heart period variability in trauma patients may predict mortality and allow remote triage. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:1107.

59. McManus, J, et al. R-wave amplitude in lead II of an electrocardiograph correlates with central hypovolemia in human beings. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1003.

60. Lerner, EB, et al. Mass casualty triage: An evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(Suppl 1):S25–S34.

61. Cap, AP. Tranexamic acid for trauma patients: A critical review of the literature. J Trauma. 2011;71(Suppl):S9–S14.

62. Roberts, I, et al. CRASH-2 collaborators: The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1096–1101.

63. Heck, JJ, Byers, D. Chemical and biological agents: Implications for TEMS. Tactical Edge. 2000;19:52.

64. Carmona, RH, Rasumoff, D. Forensic aspects of tactical emergency medical support. Tactical Edge. 1992;10:54.

65. Heggie, TW, Heggie, TM. Search and rescue trends and the emergency medical service workload in Utah’s National Parks. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:164–171.

66. Urban Search & Rescue. www.fema.gov/emergency/usr/index.shtm.

67. Cone, D. Rescue from the rubble: Urban search and rescue. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2000;4:352.

68. U.S. Department of Homeland Security/Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Response System Field Operations Guide. Washington, DC:U.S. Department of Homeland Security/FEMA; 2003. www.fema.gov/doc/emergency/usr/usrfog3.doc.

69. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), US&R Response System Task Force Medical Team Training Manual. Washington, DC:FEMA; 1997. www.fema.gov.

70. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). National Urban Search and Rescue Response System Task Force Equipment Cache List. www.fema.gov.

71. Macintyre, AG, Barbera, JA, Petinaux, BP. Survival interval in earthquake entrapments: Research findings reinforced during the 2010 Haiti earthquake response. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5:13–22.

72. Ashkenazi, I, et al. Prehospital management of earthquake casualties buried under rubble. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2005;20:22–33.

73. Vandholder, R, et al. Acute renal failure related to crush syndrome: Towards an era of seismo-nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1517.

74. Kazancioglu, R, et al. The characteristics of infections in crush syndrome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:202.

75. Niles, JK, et al. Comorbid trends in World Trade Center cough syndrome and probable posttraumatic stress disorder in firefighters. Chest. 2011;140:1146–1154.