7 Tachycardia and Bradycardia

Cardiac arrhythmias, a common problem encountered in the intensive care unit (ICU), increase the length of stay and represent a major source of morbidity.1 Clinical issues such as electrolyte derangements (particularly those related to potassium and magnesium ion concentrations), acidemia, hypoxia, cardiac ischemia or structural defects, and catecholamine excess (exogenous or endogenous) can play important roles in the cause of arrhythmias. Treatment of these arrhythmias depends most importantly on the cardiac physiology of the patient but also on the ventricular response rate and duration of the arrhythmia.

The two major categories of cardiac arrhythmias are defined by heart rate: bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats per minute [bpm]) and tachycardia (heart rate >100 bpm). Asymptomatic bradycardia does not carry a poor prognosis, and in general no therapy is indicated.2 Bradycardia with or without hypotension should prompt a consideration of metabolic disturbances, hypoxemia, drug effects, and myocardial ischemia. Other causes of bradycardia are shown in Table 7-1.

TABLE 7-1 Common Causes of Bradycardia

The recommended initial therapy for bradycardia that is leading to inadequate cardiac output and organ perfusion is 1 mg atropine intravenously (IV). The underlying cause for bradycardia should be investigated; if it is of abrupt onset, hypoxemia or acidosis can be quickly excluded by obtaining an arterial blood gas measurement. If the patient is unresponsive, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are indicated and should be instituted promptly. If the patient is already intubated, disconnect the ventilator and manually ventilate the patient (using an Ambu bag) to ensure adequate ventilation and oxygenation. Mucous plugging of the endotracheal tube or airways should be excluded in an acutely hypoxemic patient. Once these conditions are excluded, evaluate the electrocardiogram (ECG) for evidence of second- or third-degree heart block or ischemic changes. Aminophylline (100 mg IV) has been reported to correct ischemic heart block.3 Insertion of a temporary transvenous pacemaker may be indicated in the setting of ischemic heart block, because further deterioration can occur unpredictably.

Sinus tachycardia is probably the most common dysrhythmia encountered in the ICU and often occurs as a response to a sympathetic stimulus (e.g., hypoxia, vasopressors, inotropes, pain, dehydration, or hyperthyroidism). The first step is to review the patient’s medication list, including infusions, to exclude an iatrogenic etiology for the tachycardia. Treatment focuses on identifying and trying to correct the underlying cause. In trauma and postsurgical patients, tachycardia can be a sign of bleeding and hypovolemia. It is usually reasonable to administer an intravascular volume challenge (e.g., 500 mL of colloid solution in adults) and check the hemoglobin concentration. Sinus tachycardia and hypertension can be manifestations of opioid withdrawal, failure of a ventilator weaning trial, or inadequate sedation. Most patients at high risk for coronary disease warrant prophylactic treatment with a β-adrenergic blocker to prevent myocardial ischemia secondary to a high “rate-pressure product” and high myocardial oxygen demand.4,5 In particular, perioperative patients with significant cardiac risk should have titrated therapy with a β-adrenergic blocker to maintain the heart rate at less than 80 bpm unless significant contraindications exist.6

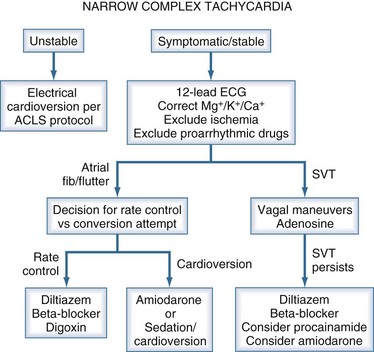

Sustained regular tachycardia (heart rate >160 bpm) associated with a narrow QRS complex on the ECG often has a reentrant mechanism as the etiology. Reentrant narrow complex tachycardia is more prevalent in females and usually is not associated with structural heart disease. The key treatment is to block AV conduction.1 These dysrhythmias can often be converted with carotid sinus massage. Adenosine can be administered (6 mg IV, followed by 12 mg IV if no response to the lower dose) if sequential carotid sinus massage fails to abort the dysrhythmia or is contraindicated. Patients presenting with reentrant supraventricular tachycardia in the ICU often have a past history of this dysrhythmia. β-Adrenergic blockers or calcium channel blockers are reasonable choices for both acute conversion and maintenance therapy. Specific β-adrenergic blockers include metoprolol (5 mg IV every 5 minutes until therapeutic effect is achieved) or esmolol (loading dose of 500 µg/kg over 1 minute, then 50 µg/kg/min infusion). Esmolol can be rebolused (500 µg/kg and the drip titrated to a maximum of 400 µg/kg/min). For diltiazem, use 5- or 10-mg boluses, using higher doses only after it is determined that administration of the agent does not lead to arterial hypotension.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the general population increases exponentially with age, from 0.9% at 40 years to 5.9% in those older than 65.7 The most important risk factors for development of AF in the general population are structural heart disease (70% in the Framingham study8 over a 22-year follow-up), hypertension (50%),8 valvular heart disease (34%),9 and left ventricular hypertrophy. AF should be approached in the following manner: find the cause and try to fix it; if the underlying problem is not fixable, consider rate control and anticoagulation. AF with rapid ventricular response can cause significant hemodynamic instability requiring emergent electrical cardioversion (biphasic defibrillator). The initial attempt should be synchronized, using 50 J of energy. If unsuccessful, subsequent cardioversion attempts should use escalating energy levels (e.g., 100, 120, 150, 200 J). AF with rapid ventricular response in the absence of hemodynamic instability can be managed initially by using drugs or other interventions to provide rate control. The goal should be to reduce heart rate to less than 120 bpm. First, minimize adrenergic stimulation by instituting mechanical ventilation if high work of breathing and respiratory failure appear to be contributing factors. Reduce the rate of catecholamine (epinephrine, dobutamine, and/or dopamine) infusions if possible. If the patient is not currently receiving treatment with inotropes or vasopressors, consider β-adrenergic blockade as first-line therapy. Metoprolol (5 mg IV every 5 minutes) or esmolol (500 µg/kg over 1 minute, then 50 µg/kg/min infusion) are reasonable choices. A trial of diltiazem (5 to 10 mg IV bolus, followed by an infusion of 5 to 20 mg/h) also can be used. If the patient requires treatment with β-adrenergic inotropic agents to support cardiac output, amiodarone (150 mg IV bolus, followed by an infusion of 1 mg/min for 6 hours, followed by an infusion 0.5 mg/min) is a reasonable choice for both rate control and conversion therapy. Amiodarone can cause lung toxicity, even with short-term therapy, so caution is warranted when using this drug, particularly in critically ill patients with underlying lung pathology.10 Digoxin is the least effective option acutely; it is relatively ineffective for controlling ventricular rate when endogenous or exogenous adrenergic tone is high.11 With new-onset AF, conversion to sinus rhythm is desirable, especially for patients who are poor candidates for anticoagulation. Conversion to sinus rhythm is also beneficial for patients with profound left ventricular dysfunction, because coordinated atrial contraction can contribute substantially to cardiac output under these conditions. In other patients, the primary goal should be to achieve (ventricular) rate control.12,13 Conversion is significantly more likely to occur during rate control with β-adrenergic blockers (e.g., esmolol) than diltiazem, but this observation actually may reflect a reduction in the spontaneous conversion rate when diltiazem is used.14,15 Amiodarone, particularly in patients with impaired ventricular function, is generally the drug of choice to achieve conversion. Anticoagulation with IV heparin should be considered if AF persists for more than 48 hours. The stroke risk in unanticoagulated patients is approximately 2% per year (0.05% per day).

Regular narrow-complex tachycardia with a heart rate between 145 and 155 bpm is typically due to atrial flutter. Carotid sinus massage or adenosine can unmask this diagnosis if it is in doubt after inspection of the 12-lead ECG (Figure 7-1). Ventricular rate control is difficult to achieve pharmacologically when the dysrhythmia is atrial flutter; accordingly, conversion to sinus rhythm is the goal. Synchronized cardioversion should be tried starting at 50 J, using appropriate conscious sedation. If cardioversion converts the rhythm to AF, use synchronized electrical cardioversion again, starting with 100 J. If atrial fibrillation persists, treat with a rate-controlling agent and anticoagulation. If refractory or recurrent atrial flutter is the problem, attempt rate control with β-adrenergic blockers or diltiazem, as for AF.

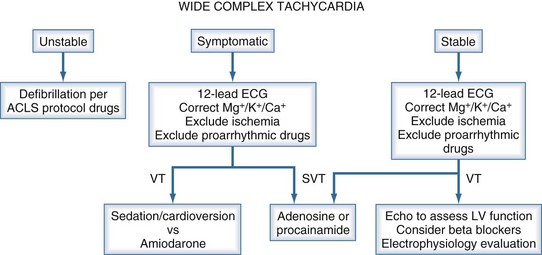

Sustained tachycardia associated with hemodynamic instability (i.e., arterial hypotension) and a wide QRS complex on the ECG should be treated as ventricular tachycardia (Figure 7-2). Synchronized cardioversion with the biphasic defibrillator at 200 J should proceed expeditiously for VT with pulse, regardless of hemodynamics. For pulseless VT, unsynchronized cardioversion at 200 J should be performed. Sustained or nonsustained VT without hemodynamic instability typically occurs in patients with cardiomyopathy or acute MI. Initial interventions should include correction of hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia (if present), reduction in the dose of β-adrenergic agonists (if being infused), and removal of physical stimuli such as pulmonary artery catheters. Amiodarone is the preferred pharmacologic therapy in this setting. Consider myocardial ischemia as the cause of monomorphic VT, and perform the appropriate diagnostic workup. The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend implantation of an internal cardiac defibrillator (ICD) for nonsustained VT in patients with coronary disease, prior MI, left ventricular dysfunction, and inducible ventricular fibrillation (VF) or sustained VT (at the time of an electrophysiologic study) that is not suppressible by a class I antiarrhythmic drug.16 Polymorphic VT should prompt a thorough evaluation of the medication list, searching for agents that prolong the QTc (Table 7-2).

TABLE 7-2 Common Medications That May Prolong the QTc

| Antibiotics |

| Antiarrhythmics |

| Psychiatric |

| Other |

Tarditi DJ, Hollenberg SM. Cardiac arrhythmias in the intensive care unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27(3):221-229.

Gregoratos G, Cheitlin MD, Conill A, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Pacemaker Implantation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(5):1175-1209.

Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(23):1834-1840.

Ashrafian H, Davey P. Is amiodarone an underrecognized cause of acute respiratory failure in the ICU? Chest. 2001;120(1):275-282.

Mooss AN, Wurdeman RL, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Esmolol versus diltiazem in the treatment of postoperative atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter after open heart surgery. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):176-180.

Polderman D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. Dutch Echocardiographic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Stress Echocardiography Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1789-1794.

1 Tarditi DJ, Hollenberg SM. Cardiac arrhythmias in the intensive care unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27(3):221-229.

2 Gregoratos G, Cheitlin MD, Conill A, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Pacemaker Implantation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1175-1209.

3 Wallace A, Layug B, Tateo I, et al. Prophylactic atenolol reduces postoperative myocardial ischemia. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:7-17.

4 Raby KE, Brull SJ, Timimi F, et al. The effect of heart rate control on myocardial ischemia among high-risk patients after vascular surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:477-482.

5 Wallace A, Layug B, Tateo I, et al. Prophylactic atenolol reduces postoperative myocardial ischemia. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:7-17.

6 Polderman D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1789-1794.

7 Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation: analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469-473.

8 Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018-1022.

9 Davidson E, Weinberger I, Rotenberg Z, Fuchs J, Agmon J. Atrial fibrillation: cause and time of onset. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:457-459.

10 Ashrafian H, Davey P. Is amiodarone an underrecognized cause of acute respiratory failure in the ICU? Chest. 2003;120:275-282.

11 David D, DiSegni E, Klein HO, et al. Inefficacy of digitalis in the control of heart rate in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation: Beneficial effect of an added beta adrenergic blocking agent. Am J Cardiol. 1978;44:1378-1382.

12 Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825-1833.

13 Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1834-1840.

14 Mooss AN, Wurdeman RL, Mohiuddin SM, et al. Esmolol versus diltiazem in the treatment of postoperative atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter after open heart surgery. Am Heart J. 2000;140:176-180.

15 Sticherling C, Tado H, Hsu W, et al. Effects of diltiazem and esmolol on cycle length and spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2002;7:81-88.

16 Gregoratos G, Abrams J, Epstein AE, et al. ACC/AHA/ NASPE 2002 guideline update for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/NASPE Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines). Circulation. 2002;106:2145-2161.