T

T-piece breathing systems, see Anaesthetic breathing systems

t tests, see Statistical tests

T wave, Wave on the ECG representing ventricular repolarisation (see Fig. 59b; Electrocardiography). Normally upright in leads I, II and V3–6; the upper height limit is 5 mm in the standard leads and 10 mm in the chest leads.

may be inverted in myocardial ischaemia, ventricular hypertrophy, mitral valve prolapse, bundle branch block and digoxin toxicity.

may be inverted in myocardial ischaemia, ventricular hypertrophy, mitral valve prolapse, bundle branch block and digoxin toxicity.

Tachycardias, see Sinus tachycardia; Supraventricular tachycardia; Ventricular tachycardia

Tachykinins. Group of neuropeptides involved in cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine and behavioural responses. Include substance P, neurokinin A and neurokinin B, which are natural agonists at NK1, NK2 and NK3 receptors, respectively. Particular interest has focused on NK1 and NK2 receptor activation, which results in bronchoconstriction, and on development of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists as antiemetic drugs.

Tachyphylaxis. Term usually referring to acute drug tolerance, usually due to depletion of receptors (or for indirectly acting drugs, depletion of neurotransmitter/signalling molecule) following repeated exposure.

Tacrine, see Tetrahydroaminocrine

Tacrolimus. Immunosuppressive drug; acts by inhibiting cytotoxic lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine expression. Used to prevent graft rejection after liver and renal transplantation. A topical preparation is available for treatment of dermatitis. Extensively bound to red blood cells and plasma proteins. Achieves steady-state concentrations after about 3 days’ administration; half-life varies from 3 to 40 h with mainly hepatic metabolism and biliary excretion.

Tamponade, see Cardiac tamponade

TAP block, see Transversus abdominis plane block

Tapentadol hydrochloride. Opioid analgesic drug, similar in structure to tramadol, used to treat moderate-to-severe pain. Acts via agonism at mu opioid receptors and inhibition of reuptake of noradrenaline. Rapidly absorbed via the oral route; undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism. Cleared by hepatic metabolism to inactive metabolites, followed by renal excretion; used with caution in patients with hepatic failure.

• Dosage: 50 mg orally 4–6-hourly, adjusted to response, maximum 600 mg daily.

• Side effects: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, dry mouth, sweating, confusion, hallucinations, seizures, respiratory depression, sedation (the latter two less commonly than with morphine). Drug dependence and withdrawal have been reported, especially following prolonged treatment.

Target-controlled infusion (TCI). Technique utilising a computer-controlled intravenous infusion device to achieve and maintain a desired target drug concentration (in plasma, or at the ‘effect site’). May be used for sedation or total intravenous anaesthesia. Requires:

a computer programmed with an algorithm based on a model of the drug’s pharmacokinetics. Familiarity with the specific model incorporated into the TCI system being used is important; the clinical effect associated with a given target concentration for one model may be different for another.

a computer programmed with an algorithm based on a model of the drug’s pharmacokinetics. Familiarity with the specific model incorporated into the TCI system being used is important; the clinical effect associated with a given target concentration for one model may be different for another.

The first licensed TCI system was for propofol, using a proprietary microprocessor that could only be used with electronically tagged pre-filled syringes. Since the expiry of the patent on propofol, several ‘open-label’ pharmacokinetic protocols have been developed and incorporated into a range of TCI devices. TCI systems for other drugs (e.g. remifentanil and sufentanil) are also available and widely used.

Absalom AR, Mani V, De Smet T, Struys MM (2009). Br J Anaesth; 103: 26–37

TB, see Tuberculosis

Teeth. Composed of the crown (consisting of enamel, dentine and pulp from outside inwards) and root. All parts may be damaged during anaesthesia; the deeper the damage, the more extensive is the treatment required. Traumatic damage is involved in about 30% of malpractice claims against anaesthetists, with a rough incidence of 1:1000 general anaesthetics and, because of its frequency, claims are rarely contested. Damage most commonly occurs during intubation or postoperatively when the patient bites on an oral airway. Preoperative assessment of the teeth is essential, noting any loose, chipped or false teeth. Patients with caries, prostheses and periodontal disease, and those in whom tracheal intubation is difficult, are at particular risk. Appropriate warnings should be given and noted on the anaesthetic chart preoperatively.

Yasny JS (2009). Anesth Analg; 108: 1564–73

See also, Dental surgery; Mandibular nerve blocks; Maxillary nerve blocks

Teicoplanin. Glycopeptide and antibacterial drug, related to vancomycin but longer acting, allowing once-daily dosing. Active against most Gram-positive organisms, as for vancomycin. 90% protein-bound, with a half-life of 7 days. Excreted unchanged in urine.

Temazepam. Benzodiazepine used in insomnia, and commonly used for premedication. Shorter acting than diazepam, with faster onset of action. Half-life is 8 h.

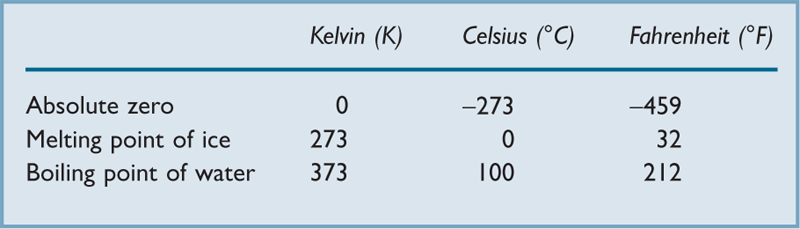

Temperature. Property of a system that determines whether heat is transferred to or from other systems. Related to the mean kinetic energy of its constituent particles. Three temperature scales are recognised: Kelvin (formerly Absolute) scale, Celsius (formerly Centigrade) scale and Fahrenheit scale (Table 42). The SI unit of temperature is the kelvin.

[Anders Celsius (1701–1744), Swedish scientist; Gabriel D Fahrenheit (1686–1736), German scientist]

Temperature measurement. Performed routinely as part of basic monitoring in ICUs. Used perioperatively to monitor heat loss during anaesthesia and detect hyperthermia.

– thermocouple: relies on the Seebeck effect; i.e. the production of voltage at the junction of two different conductors joined in a loop; the magnitude of the voltage generated is proportional to the temperature difference between the two junctions. The circuit thus consists of a measuring junction and a reference junction, with measurement of the voltage difference between the two. Because voltage is also produced at the reference junction, electrical manipulation is required to compensate for changes in temperature at the latter.

– gas expansion thermometers, e.g. an anaeroid gauge used for pressure measurement is calibrated in units of temperature. Accuracy is poor and calibration may be difficult.

nasopharyngeal and bladder: similar to oesophageal.

nasopharyngeal and bladder: similar to oesophageal.

blood: thermistors incorporated into pulmonary artery catheters allow continuous measurement.

blood: thermistors incorporated into pulmonary artery catheters allow continuous measurement.

[Thomas J Seebeck (1770–1831), Russian-born German physicist]

Temperature regulation. Humans are homeothermic, maintaining body core temperature at 37 ± 1°C. The core usually includes cranial, thoracic, abdominal and pelvic contents, and variable amounts of the deep portions of the limbs. Temperature is lowest at night and highest in mid-afternoon, also varying with the menstrual cycle.

Constant temperature is required for optimal enzyme activity. Denaturation of proteins occurs at 42°C. Loss of consciousness occurs at hypothermia below 30°C.

• Mechanisms of heat loss/gain:

– from metabolism (mainly in the brain, liver and kidneys): approximately 80 W is produced in an average man under resting conditions. This would raise body temperature by about 1°C/h if totally insulated. Vigorous muscular activity may increase heat production by up to 20 times. In babies, brown fat produces much heat.

– radiation from the skin. May account for 40% of total loss.

– convection: related to airflow (e.g. ‘wind chill’). Accounts for up to 40% of total loss.

– conduction: of little importance in air, but significant in water.

Temperature-sensitive cells are present in the anterior hypothalamus (thought to be the most important site), brainstem, spinal cord, skin, skeletal muscle and abdominal viscera. Peripheral temperature receptors are primary afferent nerve endings and respond to cold and hot stimuli via Aδ and C fibres respectively. Central control of thermoregulation is by the hypothalamus. Efferents pass via the sympathetic nervous system to blood vessels, sweat glands and piloerector muscles. Local reflexes are also involved. Efferents also pass to somatic motor centres in the lower brainstem to cause shivering, and to higher centres.

behavioural, e.g. curling up in the cold, wearing appropriate clothing.

behavioural, e.g. curling up in the cold, wearing appropriate clothing.

skin blood flow: may be altered by vasodilatation or vasoconstriction of skin vessels, and by opening or closing of arteriovenous anastomoses in the skin. Affects all routes of heat loss. Alteration alone is sufficient to maintain constant body temperature in environments of 20–28°C in adults and 35–37°C in neonates (thermoneutral range).

skin blood flow: may be altered by vasodilatation or vasoconstriction of skin vessels, and by opening or closing of arteriovenous anastomoses in the skin. Affects all routes of heat loss. Alteration alone is sufficient to maintain constant body temperature in environments of 20–28°C in adults and 35–37°C in neonates (thermoneutral range).

shivering and piloerection (reduced or absent in babies, brown fat metabolism occurring instead). Reflex shivering can hinder induced hypothermia; measures to inhibit shivering include use of neuromuscular blocking drugs, α2-adrenergic receptor agonists and skin surface warming (with core cooling).

shivering and piloerection (reduced or absent in babies, brown fat metabolism occurring instead). Reflex shivering can hinder induced hypothermia; measures to inhibit shivering include use of neuromuscular blocking drugs, α2-adrenergic receptor agonists and skin surface warming (with core cooling).

Pitoni S, Sinclair HL, Andrews PJD (2011). Curr Opin Crit Care; 17: 115–21

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Synovial joint between the mandibular condyle and the articular surface of the squamous temporal bone. Protrusion, retraction and grinding movements of the lower jaw occur by a gliding mechanism whereas mouth opening and closing involve gliding and hinging movements. Joint stability is least when the mouth is fully open (e.g. during laryngoscopy) and forward dislocation may occur. Affected by rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative disease, ankylosing spondylitis and systemic sclerosis. Mouth opening may be severely limited, hindering laryngoscopy.

Tenecteplase. Fibrinolytic drug, used in acute management of acute coronary syndromes. Binds to fibrin, the resultant complex converting plasminogen to plasmin, which dissolves the fibrin.

Tension. In physics, another word for force, implying stretching (cf. compression). Also refers to the partial pressure of a gas in solution.

Tension time index, Area between tracings of left ventricular pressure and aortic root pressure during systole, multiplied by heart rate (see Fig. 61; Endocardial viability ratio). Represents myocardial workload and hence O2 demand; when taken in conjunction with diastolic pressure time index, it may indicate the myocardial O2 supply/demand ratio and the likelihood of myocardial ischaemia.

Terbutaline sulphate. β-Adrenergic receptor agonist, used as a bronchodilator drug and tocolytic drug. Has similar effects to salbutamol, but possibly has less cardiac effect.

• Dosage:

250–500 µg im/sc qds as required.

250–500 µg im/sc qds as required.

250–500 µg iv slowly, repeated as required. 1–5 µg/min infusion may be used (containing 3–5 µg/ml). Up to 25 µg/min may be required in premature labour (see Ritodrine).

250–500 µg iv slowly, repeated as required. 1–5 µg/min infusion may be used (containing 3–5 µg/ml). Up to 25 µg/min may be required in premature labour (see Ritodrine).

1–2 puffs by aerosol (250–500 µg) tds/qds.

1–2 puffs by aerosol (250–500 µg) tds/qds.

Terlipressin, see Vasopressin

Terminal care, see Palliative care; Withdrawal of treatment in ICU

Test dose, epidural. In epidural anaesthesia, injection of a small amount of local anaesthetic agent through the catheter before injection of the main dose, in order to identify accidental subarachnoid or iv placement of the catheter. Less commonly performed before ‘through the needle’ epidural block, since leakage of CSF or blood should be more easily noticeable.

Controversial, since it is not always reliable. The volume and strength of the test solution are also controversial. 3 ml 2% lidocaine with adrenaline 1:200 000 has been suggested as the ideal solution; subarachnoid injection produces spinal anaesthesia within 2–3 min, and iv injection produces tachycardia within 90 s. Injection of fentanyl 50–100 µg or 1 ml air (with Doppler monitoring) has also been used. In modern ‘low-dose’ techniques (e.g. epidural analgesia for labour), each dose ‘acts as its own test’ since a standard dose of e.g. 10 ml bupivacaine 0.1% with 20 µg fentanyl would be expected to produce noticeable effects were it to be injected subarachnoid or iv without causing a dangerously high block or severe systemic toxicity.

Tetanic contraction. Sustained muscle contraction caused by repetitive electrical stimulation of a motor nerve. About 25 Hz stimulation is required for frequent enough action potentials to produce it, although the necessary rate varies according to the muscle studied. The force produced exceeds that of single muscle twitches. During tetanic contraction, acetylcholine is mobilised from reserve stores to the readily available pool.

Produced during neuromuscular blockade monitoring.

See also, Neuromuscular junction; Neuromuscular transmission; Post-tetanic potentiation

Clinical features are caused by a potent exotoxin, tetanospasmin, which moves along peripheral nerves to the spinal cord, where it blocks release of neurotransmitters at inhibitory neurons, causing muscle spasm and autonomic disturbance. Incubation period is 3–21 days (average 7 days). Local infection may cause muscle spasm around the site of injury; generalised tetanus is characterised by trismus, irritability, rigidity and opisthotonos. Cardiac arrhythmias/arrest and hypertension may occur due to sympathetic hyperactivity. As binding of tetanospasmin is irreversible, recovery depends on formation of new nerve terminals. The diagnosis is based on clinical findings but the spatula test (touching the oropharynx with a wooden spatula; in tetanus this results in spasm of the masseter muscles causing biting of the spatula) is highly sensitive and specific for tetanus.

human antitetanus immunoglobulin (5000–10 000 units): neutralises circulating toxin.

human antitetanus immunoglobulin (5000–10 000 units): neutralises circulating toxin.

surgical excision and debridement of the wound.

surgical excision and debridement of the wound.

metronidazole to eradicate existing organisms.

metronidazole to eradicate existing organisms.

sedation, neuromuscular blocking drugs and IPPV may be required. Dantrolene and magnesium sulphate have been used. The latter reduces sympathetic overactivity and reduces spasm by decreasing presynaptic activity.

sedation, neuromuscular blocking drugs and IPPV may be required. Dantrolene and magnesium sulphate have been used. The latter reduces sympathetic overactivity and reduces spasm by decreasing presynaptic activity.

Active immunisation with tetanus vaccine should always be performed in trauma and burns unless within 5–10 years of previous administration. Antitetanus immunoglobulin is given to non-immune patients with heavily contaminated or old wounds.

Gibson K, Bonaventure Uwineza J, Kiviri W, Parlow J (2009). Can J Anaesth; 56: 307–15

Tetany. Increased sensitivity of excitable cells, manifested as peripheral muscle spasm. Usually facial and carpopedal, the shape of the hand in the latter termed main d’accoucheur (French: obstetrician’s hand). Usually caused by hypocalcaemia; it also occurs in hypomagnesaemia and may be hereditary.

Tetracaine hydrochloride (Amethocaine). Ester local anaesthetic agent, introduced in 1931. Widely used in the USA for spinal anaesthesia; in the UK, used only for topical anaesthesia, e.g. in ophthalmology. More potent and longer lasting than lidocaine, but more toxic. Toxicity resembles that of cocaine. Weak base with a pK of 8.5. Rapidly absorbed from mucous membranes. Hydrolysed completely by plasma cholinesterase to form butylaminobenzoic acid and dimethylaminoethanol. Administration: 0.5–1% solution for spinal anaesthesia; 0.4–0.5% for epidural anaesthesia; 0.1–0.2% solution for infiltration, usually with adrenaline; 0.5–1% solutions for surface analgesia.

Available in a 4% gel (available over the counter without prescription) for topical anaesthesia of the skin, e.g. before venepuncture. The melting point of the drug is lowered by the formation of specific hydrates within the gel. The resultant oil globules penetrate the skin readily with onset of action about 30–45 min; effects last 4–6 h. Skin blistering may occur. Has been combined with lidocaine and a heating compound in a plaster, for topical anaesthesia before venepuncture.

Tetracycline. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drug, used mainly for chlamydia, rickettsia, spirochaete and brucella infections, certain mycoplasma infections, acne, acute exacerbations of COPD and leptospirosis. Several tetracyclines exist, with tetracycline itself the only one administered iv. Has also been instilled into the pleural cavity to treat recurrent pleural effusions.

Tetrahydroaminocrine hydrochloride (Tacrine). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor formerly used to prolong the action of suxamethonium. Also used prophylactically to reduce muscle pains following suxamethonium, and as a central stimulant. Used as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

[Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), German neurologist and pathologist]

Tetrodotoxin. Toxin obtained from puffer fish, that selectively blocks neuronal voltage-gated fast sodium channels. Used experimentally, e.g. for investigating neuromuscular transmission.

Thalassaemia. Group of autosomally inherited disorders involving decreased production of the α or β chains of haemoglobin (Hb). More common in Mediterranean, African and Asian areas. Severity is related to the pattern of inheritance of the Hb genes (normally, one β gene and two α genes are inherited from each parent).

– not apparent immediately as fetal haemoglobin does not contain β chains.

– heterozygous β thalassaemia (thalassaemia minor) produces mild (often asymptomatic) anaemia, but may be associated with other types of Hb (e.g. HbC, HbE, HbS); resultant anaemia may vary from mild to severe.

– homozygous β thalassaemia (Cooley’s anaemia; thalassaemia major) results in severe anaemia in infancy, with no production of HbA. Features include craniofacial bone hyperplasia, hepatosplenomegaly and cardiac failure. Haemosiderosis may occur due to repeated blood transfusion. Usually fatal before adulthood, although bone marrow transplantation may offer a cure. Some genetic subtypes are associated with a milder clinical course (thalassaemia intermedia).

Peters M, Heijboer H, Smiers F, Giordano PC (2012). Br Med J; 344: e228

Theophylline. Bronchodilator drug, used alone or in combination with ethylenediamine as aminophylline.

Thermal conductivity detector, see Katharometer

Thermistor, see Temperature measurement

Thermocouple, see Temperature measurement

Thermodilution cardiac output measurement, see Cardiac output measurement

Thermoneutral range. Temperature range in which temperature regulation may be maintained by changes in skin blood flow alone. Corresponds to the temperature that feels ‘comfortable’. About 20–28°C in adults and 35–37°C in neonates. Neonatal metabolic rate and mortality are reduced if body temperature is kept within the thermoneutral range.

Thiamylal sodium. IV anaesthetic agent, with similar properties to thiopental. Unavailable in the UK.

Thiazide diuretics. Group of diuretics used to treat mild hypertension, oedema caused by cardiac failure and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Chlorothiazide was the first to be studied but many now exist, e.g. bendroflumethiazide (bendrofluazide). Act mainly at the proximal part of the distal convoluted tubule of the nephron, where they inhibit sodium reabsorption. They also act at the proximal tubule, causing weak inhibition of carbonic anhydrase and increasing bicarbonate and potassium excretion, and have a direct vasodilator action. Their antihypertensive action increases only slightly as dosage is increased. Rapidly absorbed from the GIT with onset of action within 1–2 h, lasting 12–24 h. Some non-thiazide drugs have thiazide-like properties (e.g. chlortalidone, metolazone).

Side effects include hypokalaemia, hyponatraemia, hyperuricaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypochloraemic alkalosis, hyperglycaemia, hypercholesterolaemia, exacerbation of renal and hepatic impairment, impotence, and, rarely, rashes and thrombocytopenia.

Thiazolidinediones. Oral hypoglycaemic drugs used in management of type II diabetes mellitus. Bind to a nuclear receptor, PPARγ, in adipose cells, liver and skeletal muscle, increasing sensitivity to insulin. Not indicated for monotherapy; usually used in combination with a biguanide or sulphonylurea. Agents include pioglitazone (restricted in some countries because of the risk of bladder cancer), rosiglitazone (restricted in the USA and unavailable in Europe because of the risk of cardiovascular events) and troglitazone (withdrawn because of the risk of hepatitis).

Thigh, lateral cutaneous nerve block. Provides analgesia of the anterolateral thigh/knee, e.g. for leg surgery (especially skin graft harvesting) and diagnosis of meralgia paraesthetica (numbness and paraesthesia caused by lateral cutaneous nerve compression by the inguinal ligament, under which it passes).

With the patient supine, a needle is introduced perpendicular to the skin, 2 cm medial and caudal to the anterior superior iliac spine. A click is felt as the fascia lata is pierced. 10–15 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected in a fan shape laterally.

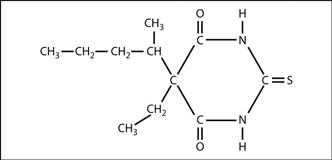

Thiopental sodium (Thiopentone; 5-ethyl-5-(1-methylbutyl)-2-thiobarbiturate). IV anaesthetic agent, synthesised in 1932 and first used in 1934 by Lundy and Waters. Also used in refractory status epilepticus. The sulphur analogue of pentobarbitone (Fig. 154). Stored as the sodium salt, a yellow powder with a faint garlic smell, with 6% anhydrous sodium carbonate added to prevent formation of (insoluble) free acid when exposed to atmospheric CO2 and presented in an atmosphere of nitrogen. Most commonly used as a 2.5% solution, with pH of 10.5. pKa is 7.6; at a pH of 7.4 about 60% is non-ionised. The solution is stable for 24–36 h after mixing, although the manufacturers recommend discarding after 7 h.

About 85% bound to plasma proteins after injection. Follows a multicompartmental pharmacokinetic model after a single iv injection, with redistribution from vessel-rich tissues (e.g. brain) to lean body tissues (e.g. muscle), with return of consciousness. Slower redistribution then occurs to vessel-poor tissues (e.g. fat: see Fig. 88; Intravenous anaesthetic agents).

• Effects:

– smooth, occurring within one arm–brain circulation time. Involuntary movements and painful injection are rare.

– recovery within 5–10 min after a single dose.

– causes dose-related direct myocardial depression, decreasing cardiac output and causing compensatory tachycardia with increased myocardial O2 demand. Cardiovascular depression is related to speed of injection and is exacerbated by hypovolaemia.

– has little effect on SVR but may decrease venous vascular tone, reducing venous return.

– causes dose-related depression of the respiratory centre, decreasing the responsiveness to CO2 and hypoxia. Apnoea is common after induction.

– laryngospasm readily occurs following laryngeal stimulation.

– has been implicated in causing bronchospasm, but this is disputed.

– decreases pain threshold (antanalgesia).

– reduces cerebral perfusion pressure, ICP and cerebral metabolism.

– causes brief skeletal muscle relaxation at peak CNS effect.

– reduces renal and hepatic blood flow secondary to reduced cardiac output. Causes hepatic enzyme induction.

Metabolised by oxidation in the liver (10–15% per hour), with < 1% appearing unchanged in the urine. Desulphuration to pentobarbitone may also occur following prolonged administration. Elimination half-life is 5–10 h. Up to 30% may remain in the body after 24 h. Accumulation may occur on repeated dosage.

extravenous injection causes pain and erythema.

extravenous injection causes pain and erythema.

intra-arterial injection causes intense pain, and may cause distal blistering, oedema and gangrene, attributed to crystallisation of thiopental within arterioles and capillaries, with local noradrenaline release and vasospasm. Endothelial damage and subsequent inflammatory reaction have been suggested as being more likely. Particularly hazardous with the 5% solution, now rarely used. Treatment: leaving the needle/cannula in the artery, the following may be injected:

intra-arterial injection causes intense pain, and may cause distal blistering, oedema and gangrene, attributed to crystallisation of thiopental within arterioles and capillaries, with local noradrenaline release and vasospasm. Endothelial damage and subsequent inflammatory reaction have been suggested as being more likely. Particularly hazardous with the 5% solution, now rarely used. Treatment: leaving the needle/cannula in the artery, the following may be injected:

– vasodilators, traditionally papaverine 40 mg, tolazoline 40 mg, phentolamine 2–5 mg, to reduce arterial spasm.

– local anaesthetic, traditionally procaine 50–100 mg (also a vasodilator), to reduce pain.

– heparin, to reduce subsequent thrombosis.

Brachial plexus block and stellate ganglion block have been used to encourage vasodilatation (before heparinisation). Postponement of surgery has been suggested.

respiratory/cardiovascular depression as above.

respiratory/cardiovascular depression as above.

adverse drug reactions. Severe anaphylaxis is rare (1:14 000–35 000), typically occurring after several previous exposures.

adverse drug reactions. Severe anaphylaxis is rare (1:14 000–35 000), typically occurring after several previous exposures.

• Dosage:

3–6 mg/kg iv. Requirements are reduced in hypoproteinaemia, hypovolaemia, the elderly and critically ill patients. Injection should be over 10–15 s, with a pause after the expected adequate dose before further administration.

3–6 mg/kg iv. Requirements are reduced in hypoproteinaemia, hypovolaemia, the elderly and critically ill patients. Injection should be over 10–15 s, with a pause after the expected adequate dose before further administration.

has also been given rectally: 40–50 mg/kg as 5–10% solution.

has also been given rectally: 40–50 mg/kg as 5–10% solution.

Fig. 154 Structure of thiopental

Thiosulphate, see Cyanide poisoning

Third gas effect, see Fink effect

Third space. ‘Non-functional’ interstitial fluid compartment, to which fluid is transferred following trauma, burns, surgery and other conditions, including infection, pancreatitis. Most of the fluid originates from the ECF, but some movement from intracellular fluid also occurs. Includes fluid lost to the transcellular fluid compartment, e.g. ascites, bowel contents. Although not lost from the body, fluid shifts to the third space are equivalent to functional ECF losses and must be accounted for when estimating fluid balance. Losses may exceed 10 ml/kg/h during abdominal surgery, and should be replaced initially with 0.9% saline or Hartmann’s solution, although colloids may also be used.

• Contents (see Fig. 26; Brachial plexus and Fig. 104; Mediastinum):

– right side: brachiocephalic vessels; vagus; phrenic nerve.

– left side: common carotid/subclavian arteries; vagus; brachiocephalic vein; phrenic nerve.

Thoracic inlet X-ray views may be useful if tracheal compression or displacement is suspected.

Thoracic surgery. The first pneumonectomy was performed in 1895 by Macewan. Surgical and anaesthetic techniques improved with experience of treating chest injuries during World War II. The commonest indication for thoracic surgery was formerly TB and empyema but is now malignancy, especially bronchial carcinoma.

• Main anaesthetic principles:

– preoperative assessment of exercise tolerance, cough and haemoptysis. Ischaemic heart disease secondary to smoking is common. Cyanosis, tracheal deviation, stridor, abnormal chest wall movement, pleural effusion and systemic features of malignancy may be present.

– investigations include CXR, CT scanning and MRI. Distortion of the trachea/bronchi should be noted as this may hinder endobronchial intubation. Rarely, bronchography is performed, e.g. in bronchiectasis. Arterial blood gas interpretation and lung function tests are routinely performed, e.g. spirometry, flow–volume loops. A poor postoperative course following pneumonectomy is suggested if any of FVC, FEV1, maximal voluntary ventilation, residual volume : total lung capacity ratio or diffusing capacity is < 50% of predicted. Pulmonary hypertension is also associated with poor outcome.

– cardiopulmonary exercise testing may be employed; a maximum O2 uptake of < 15 ml/kg/min is cited as predictive of poorer outcomes.

– preparation includes antibiotic therapy, physiotherapy and use of bronchodilator drugs as appropriate.

– premedication commonly includes anticholinergic drugs to reduce secretions.

– specific diagnostic procedures include bronchoscopy, mediastinoscopy, bronchography and oesophagoscopy.

– preoxygenation is usually employed. IV induction of anaesthesia is usually suitable; difficulties may include cardiovascular instability, airway obstruction, difficult tracheal intubation, risk of aspiration of gastric contents in oesophageal disease and problems of lesions affecting the mediastinum.

– endobronchial tubes are often used, although standard tracheal tubes are usually acceptable unless isolation of lung segments is required. Endobronchial blockers may also be used.

– large-bore iv cannulae are vital, since blood loss may be severe.

– standard monitoring is used; arterial and central venous cannulation is often employed.

– maintenance of anaesthesia is usually with standard agents and techniques. Pendelluft,  mismatch and decreased venous return secondary to mediastinal shift may also occur. Hypoxaemia is common during one-lung anaesthesia. Injector techniques and high-frequency ventilation have been used for tracheal resection.

mismatch and decreased venous return secondary to mediastinal shift may also occur. Hypoxaemia is common during one-lung anaesthesia. Injector techniques and high-frequency ventilation have been used for tracheal resection.

– positioning of the patient: the lateral position with the operative lung uppermost is usual. The arm is placed over the head, displacing the scapula upwards. Drainage of secretions from the affected lung without soiling the unaffected lung may be achieved using the Parry Brown position (prone, with a pillow under the pelvis and a 10 cm rest under the chest; the arm on the operated side overhangs the table’s edge with the head turned to the opposite side, and the table is tipped head-down so that the trachea slopes downwards).

– at closure of the chest, the lung is re-expanded after endobronchial suction. Up to 40 cmH2O airway pressure may be requested by the surgeon to test bronchial sutures. Tubes are placed for chest drainage. After pneumonectomy, chest drains are often not used; air is introduced or removed to equalise the intrapleural pressures on both sides and centralise the mediastinum. The pleural space slowly fills with fluid postoperatively, with eventual fibrosis.

– postoperative analgesia is vital to ensure adequate ventilation. Standard techniques are used, including patient-controlled analgesia, thoracic epidural anaesthesia and use of spinal opioids. Cryoanalgesia and intercostal nerve block may be performed by the surgeon whilst the chest is open.

Specific procedures and conditions include removal of inhaled foreign body, repair of bronchopleural fistula, chest trauma and bronchopulmonary lavage.

[Arthur I Parry Brown (1908–2007), London anaesthetist; Ivor Lewis (1895–1982), London surgeon]

Thoracocardiography, see Inductance cardiography

Three-in-one block, see Femoral nerve block; Lumbar plexus

Thrombin inhibitors. Group of compounds that bind to various sites on the thrombin molecule, investigated as alternatives to heparin. Includes hirudin and related substances. Ximelagatran, a prodrug for melagatran, was extensively investigated as an oral anticoagulant but withdrawn in 2006 following reports of hepatic impairment. Rivaroxaban and dabigatran are licensed for the prevention of DVT in adults undergoing elective hip or knee replacement; the latter is also used for prevention of CVA in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation.

Thrombin time, see Coagulation studies

Thrombocytopenia. Defined as a platelet count below 100 × 109/l. Common in critically ill patients.

decreased production: e.g. bone marrow depression (by drugs, infection, etc.), vitamin B12/folate deficiency, hereditary defects, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, thiazide diuretics, alcoholism.

decreased production: e.g. bone marrow depression (by drugs, infection, etc.), vitamin B12/folate deficiency, hereditary defects, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, thiazide diuretics, alcoholism.

– immune: autoantibodies (e.g. idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, malignancy, drugs (e.g. quinine, heparin, α-methyldopa), infection (e.g. HIV), alloantibodies (e.g. post-transfusion).

– non-immune: DIC, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, cardiopulmonary bypass, haemolytic–uraemic syndrome.

Patients with platelet counts above 50 × 109/l are usually asymptomatic. Bleeding time increases progressively as the count falls below 100 × 109/l. Counts below 20–30 × 109/l may be associated with spontaneous bleeding, e.g. mucocutaneous, gastrointestinal, cerebral. Diagnosis of the underlying condition requires examination of the blood film and bone marrow and coagulation studies.

Regional anaesthesia in the presence of thrombocytopenia (e.g. in obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia) is controversial, with any benefits weighed against the potential risk of spinal haematoma. Many anaesthetists would consider a platelet count above 70–80 × 109/l acceptable if there is no clinical evidence of impaired function (e.g. bruising or noticeably prolonged bleeding), coagulation studies are normal, the count has been stable for at least several days and regional anaesthesia would be particularly advantageous.

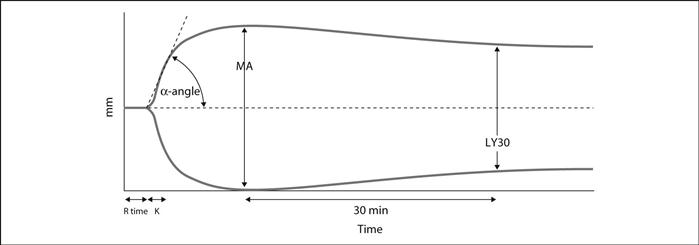

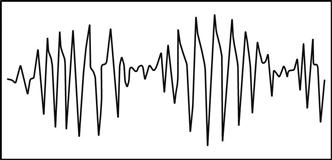

Thromboelastography (TEG). Point-of-care coagulation monitoring technique that assesses the speed and quality of clot formation (and resolution). A pin is suspended via a torsion wire in a sample of whole fresh blood held in a rotating cuvette (usually combined with a coagulation activator); as the clot forms, the rotation of the cuvette is transmitted to the pin, the movement of which thus reflects the viscoelastic properties of the clot as it forms and resolves. This movement is transduced to an electrical signal and displayed, giving the characteristic TEG trace (Fig. 155). A related technique uses an optical detector system to measure the movement of the pin (termed ROTEM or rotational thromboelastometry). Initially used mainly during liver transplantation and cardiac surgery, it is increasingly being used to guide administration of blood products in other situations involving major haemorrhage, e.g. obstetrics and trauma.

• TEG parameters and normal ranges:

clot formation/‘K’ time (time for clot firmness to reach 20 mm): 1–4 min. Prolonged by thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenaemia and anticoagulants.

clot formation/‘K’ time (time for clot firmness to reach 20 mm): 1–4 min. Prolonged by thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenaemia and anticoagulants.

maximum amplitude (MA; maximum clot strength): 55–73 mm. Parameter most influenced by platelet number and function; reduced by thrombocytopenia and antiplatelet drugs.

maximum amplitude (MA; maximum clot strength): 55–73 mm. Parameter most influenced by platelet number and function; reduced by thrombocytopenia and antiplatelet drugs.

LY30 (per cent clot lysis at 30 s): < 7.5%. Increased in early DIC.

LY30 (per cent clot lysis at 30 s): < 7.5%. Increased in early DIC.

• Advantages over standard laboratory studies:

faster acquisition of results.

faster acquisition of results.

incorporates assessment of platelet function.

incorporates assessment of platelet function.

analysis can be performed at the patient’s body temperature (thus taking into account the effect of hypothermia if present).

analysis can be performed at the patient’s body temperature (thus taking into account the effect of hypothermia if present).

ability to add activators/inhibitors to analyse specific aspects of coagulation (e.g. heparinase to assess the effect of administered heparin)

ability to add activators/inhibitors to analyse specific aspects of coagulation (e.g. heparinase to assess the effect of administered heparin)

Thromboembolism, see Coagulation; Deep vein thrombosis

Thrombolytic drugs, see Fibrinolytic drugs

Thrombophlebitis, see Intravenous fluid administration

Thromboplastin time, see Coagulation studies

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Rare disorder characterised by intravascular thrombosis, consumptive thrombocytopenia and haemolytic anaemia (due to mechanical damage to red cells). May be difficult to distinguish from haemolytic–uraemic syndrome (with which it is thought to overlap) and DIC. Often associated with increased plasma levels of large von Willebrand factor multimers and a congenital deficiency of a specific metalloprotease that cleaves it, ADAMTS13. Clinical episodes are often preceded by triggering events (e.g. surgery, infection, pregnancy) in susceptible individuals.

Typically presents with abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting and weakness. Neurological symptoms (e.g. CVA, convulsions) may also occur. Diagnosed largely clinically.

Treated by plasmapheresis, for which there is good evidence of efficacy. Immunosuppressive drugs have also been used, e.g. corticosteroids. Refractory disease has been treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Untreated, may rapidly progress to death in ~80% of cases; mortality with treatment is ~20%.

Thromboxanes. Substances related to prostaglandins, synthesised by the action of cyclo-oxygenase on arachidonic acid. Thromboxane A2 is released by platelets at sites of injury, causing vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation, and is opposed by prostacyclin. It is metabolised to thromboxane B2, which has little activity.

Thymol. Aromatic hydrocarbon used as an antioxidant in halothane and trichloroethylene. May build up inside vaporisers unless cleaned regularly. Also used as a disinfectant and deodorant, e.g. in mouthwashes.

Thyroid crisis (Thyroid storm). Rare manifestation of severe hyperthyroidism. May be triggered by stress, including surgery and infection. Features include tachycardia, arrhythmias (including VT, VF and AF), cardiac failure, fever, diarrhoea, sweating, hyperventilation, confusion and coma.

supportive, e.g. cooling, sedation, rehydration, treatment of arrhythmias (β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are usually employed). IPPV may be required in respiratory failure.

supportive, e.g. cooling, sedation, rehydration, treatment of arrhythmias (β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are usually employed). IPPV may be required in respiratory failure.

hydrocortisone 100 mg iv qds.

hydrocortisone 100 mg iv qds.

– 200 mg potassium iodide orally/iv qds.

– 60–120 mg carbimazole or 600–1200 mg propylthiouracil orally/day.

plasmapheresis and exchange transfusion have been used in severe cases.

plasmapheresis and exchange transfusion have been used in severe cases.

Thyroid gland. Largest endocrine gland, extending from the attachment of sternothyroid muscle to the thyroid cartilage superiorly, to the sixth tracheal ring inferiorly. The two lateral lobes lie lateral to the oesophagus and pharynx, with the isthmus overlying the second to fourth tracheal rings anteriorly. Arterial supply is via the superior and inferior thyroid arteries (branches of the external carotid arteries and thyrocervical trunk of the subclavian artery respectively). The external and recurrent laryngeal nerves are closely related to the superior and inferior thyroid arteries respectively.

Produces thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which increase tissue metabolism and growth. They also increase the effects of catecholamines by increasing the number and sensitivity of β-adrenergic receptors. Iodine is absorbed from the GIT as iodide and actively transported into the thyroid gland, where it is oxidised by a peroxidase and bound to thyroglobulin. Iodination of tyrosine residues of thyroglobulin produces T3 and T4, which are cleaved from the parent molecule. Both hormones are more than 99% bound to plasma proteins, including thyroxine binding globulin (TBG) and albumin. T3 is secreted in smaller amounts than T4, is 3–5 times as potent, is faster acting, and has a shorter half-life. T4 is converted to T3 peripherally.

Control of T3 and T4 production is by thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), secreted by the pituitary gland. Secretion is inhibited by T3, T4 and stress, and stimulated by thyrotrophin releasing hormone (TRH), secreted by the hypothalamus. TRH secretion is also inhibited by T3 and T4.

total plasma T3 and T4 (normally 1–3 nmol/l and 60–150 nmol/l respectively). Increased in hyperthyroidism, and when TBG levels are raised, e.g. in pregnancy, hepatitis. Decreased in hypothyroidism and when TBG levels are reduced, e.g. corticosteroid therapy, or when binding of T3 and T4 is inhibited, e.g. by phenytoin and salicylates.

total plasma T3 and T4 (normally 1–3 nmol/l and 60–150 nmol/l respectively). Increased in hyperthyroidism, and when TBG levels are raised, e.g. in pregnancy, hepatitis. Decreased in hypothyroidism and when TBG levels are reduced, e.g. corticosteroid therapy, or when binding of T3 and T4 is inhibited, e.g. by phenytoin and salicylates.

The gland also secretes calcitonin, important in calcium homeostasis, from parafollicular (C) cells.

Anaesthetic considerations of thyroid surgery: as for hyper-/hypothyroidism.

See also, Neck, cross-sectional anatomy; Sick euthyroid syndrome

Thyroidectomy, see Hyperthyroidism; Thyroid gland

Thyrotoxicosis, see Hyperthyroidism; Thyroid crisis

Tibial nerve block, see Ankle, nerve blocks; Knee, nerve blocks

Ticagrelor. Nucleoside analogue antiplatelet drug, used in combination with aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes. More effective than clopidogrel at reducing ischaemic events and all-cause mortality, but with a higher risk of minor bleeding.

Antagonises platelet P2Y12 ADP receptors, thereby inhibiting ADP-mediated platelet aggregation by blocking the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa pathway. Oral bioavailability is 35%, with peak clinical effect occurring within 2–4 h. Eliminated via hepatic metabolism, with a half-life of 7–8 h. As with clopidogrel, cessation 7 days before surgery is recommended.

Ticarcillin. Carboxypenicillin antibacterial drug, used primarily for pseudomonas infections, although also active against other Gram-negative organisms. Available in the UK only in combination with clavulanic acid.

Tick-borne diseases. Common worldwide, although uncommon in the UK; soft ticks cause a variety of skin lesions and transmit spirochaetal relapsing fevers whilst hard ticks are the vectors for arboviral haemorrhagic fevers, encephalitis, typhus and Lyme disease. Rarely, tick bites may result in ascending flaccid paralysis, leading to respiratory and bulbar involvement within a few days unless the tick is removed. The causative agent is unknown. Treatment is supportive, with appropriate antibacterial drugs (e.g. tetracyclines or aminoglycosides).

Graham J, Stockley K, Goldman RD (2011). Pediatr Emerg Care; 27: 141–7

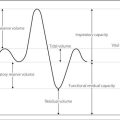

Tidal volume. Volume of gas inspired and expired with each breath. Normally 7 ml/kg. Measured using spirometers or respirometers. ‘Effective’ tidal volume equals tidal volume minus dead space volume.

Tigecycline. Antibacterial drug related to tetracycline; active against Gram-positive and -negative organisms and some anaerobic bacteria. Reserved for complicated soft tissue and abdominal infections.

Time constant (τ). Expression used to describe an exponential process. Equals the time in which the process would be completed if the rate of change were maintained at its initial value. May also be described as the ratio of quantity present to the rate of change of quantity at that moment. At 1τ the process is 63% complete (i.e. 37% of the initial quantity remains), at 2τ it is 86.5% complete, and at 3τ it is 95% complete. After 6τ the process is 99.75% complete.

When used to refer to passive expiration of air from the lungs, τ equals compliance × resistance; thus stiff alveoli served by narrow airways empty at similar rates to compliant alveoli served by wide airways. May also be applied to the washout of nitrogen from the lungs during preoxygenation; τ equals FRC divided by alveolar ventilation.

Time to sustained respiration. Time for adequate regular respiration to occur in the neonate after delivery, without stimulation. Related to fetal wellbeing and respiratory depression caused by drugs administered to the mother before delivery.

See also, Fetus, effects of anaesthetic drugs on; Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia

Tinzaparin sodium, see Heparin

Tirofiban. Antiplatelet drug, used in acute coronary syndromes, within 12 h of the last episode of chest pain. Acts by reversibly inhibiting activation of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex on the surface of platelets.

• Dosage: 400 ng/kg/min iv for 30 min, followed by 100 ng/kg/min for at least 48 h (and during and 12–24 h after percutaneous coronary intervention if performed). If angiography < 4 h after diagnosis, 2500 ng/kg iv bolus at start of procedure, followed by infusion of 150 ng/kg/min for 18–24 h.

Tissue oxygen tension, see Oxygen, tissue tension

Tobramycin. Aminoglycoside and antibacterial drug with similar activity to gentamicin but more active against pseudomonas, although less active against other Gram-negative organisms.

Tocainide hydrochloride. Class Ib antiarrhythmic drug previously used for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Withdrawn from use in the UK and USA due to severely toxic side effects, including life-threatening agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, hepatitis, pneumonitis and an SLE-like syndrome.

Tocolytic drugs. Used to inhibit uterine contractions when premature delivery of the fetus is threatened, to prevent uterine activity during/after incidental maternal surgery or fetal surgery, and to relax the uterus acutely, e.g. in fetal distress, obstructed delivery or uterine inversion. Drugs traditionally used are β2–adrenergic receptor agonists and include ritodrine, salbutamol and terbutaline. Side effects may persist after discontinuation of the infusion; these include tachycardia, arrhythmias, hypotension and occasionally pulmonary oedema (unclear mechanism, but thought to involve increased pulmonary hydrostatic pressure; fluid administration and concomitant corticosteroids may also contribute). Arrhythmias may occur if halothane is subsequently used.

Other tocolytic drugs include atosiban (an oxytocin antagonist), which is more expensive but has fewer side effects than β2-agonists in preterm labour (although it may cause nausea, vomiting, tachycardia and hypotension). Nifedipine, magnesium sulphate and inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis (e.g. indometacin) also cause tocolysis but are not widely used in the UK. GTN patches have also been used. Acutely, GTN 100–400 µg iv or sublingually is also used.

Tolazoline hydrochloride. α-Adrenergic receptor antagonist, structurally related to phentolamine. Traditionally used by iv infusion to relieve arterial spasm following accidental intra-arterial injection of thiopental. Also used to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance, e.g. in congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Tolerance. Progressively decreasing response to repeated administration of a drug. May result from altered number of receptors, altered response to receptor activation, altered pharmacokinetics (e.g. enzyme induction) or development of physiological compensatory mechanisms. Classically occurs with morphine.

palatoglossus and styloglossus: pass from the palate and styloid process respectively.

palatoglossus and styloglossus: pass from the palate and styloid process respectively.

intrinsic muscles: include vertical, longitudinal and transverse fibres.

intrinsic muscles: include vertical, longitudinal and transverse fibres.

The tone of genioglossus is important in preventing approximation of the tongue and posterior pharyngeal wall, which results in airway obstruction. Genioglossus tone varies with respiration and is maximal in inspiration. It also decreases during sleep; this may contribute to the development of sleep apnoea. Anaesthetic and sedative agents decrease this tone and thus predispose to obstruction, which may be relieved by elevating the jaw, placing the patient in the lateral position, and use of pharyngeal airways.

Macroglossia predisposes to respiratory obstruction and may hinder tracheal intubation, e.g. in acromegaly, Down’s syndrome and light chain amyloidosis. It may also occur after posterior fossa neurosurgery. Tongue piercing studs should be removed preoperatively.

Tonicity. Refers to the effective osmotic pressure of solutions in relation to that of plasma. Thus a urea solution may be isosmotic with plasma but its effective osmotic pressure (and thus tonicity) falls after infusion because urea distributes evenly across cell membranes. Similarly, 5% dextrose solution is isosmotic with plasma but hypotonic when infused since the dextrose is metabolised by red blood cells leaving water.

Tonometry, gastric, see Gastric tonometry

Tonsil, bleeding. Haemorrhage usually occurs within a few hours postoperatively, but may be delayed.

hidden blood loss if the patient (usually a child) swallows it; hypovolaemia may thus be severe before diagnosis is made.

hidden blood loss if the patient (usually a child) swallows it; hypovolaemia may thus be severe before diagnosis is made.

risk of aspiration of gastric contents (mostly altered blood).

risk of aspiration of gastric contents (mostly altered blood).

airway management and tracheal intubation may be difficult if bleeding is torrential.

airway management and tracheal intubation may be difficult if bleeding is torrential.

significant amounts of the anaesthetic agents used previously may still be present.

significant amounts of the anaesthetic agents used previously may still be present.

possibility of an undiagnosed coagulation disorder.

possibility of an undiagnosed coagulation disorder.

experienced assistance is required. Each of the following techniques has its advocates:

experienced assistance is required. Each of the following techniques has its advocates:

– inhalational induction in the left lateral position (with suction available), traditionally using halothane (superseded by sevoflurane) in O2, and tracheal intubation during spontaneous ventilation. The main advantage is the maintenance of spontaneous ventilation if intubation is difficult. However, induction may be prolonged and hindered by bleeding and gagging and the high concentrations of volatile agent required plus hypovolaemia may cause significant hypotension.

– rapid sequence induction using a small dose of iv agent, e.g. thiopental followed by suxamethonium and intubation. Advantages of this technique include rapidity of intubation and the greater familiarity of most anaesthetists with it. However, it should only be attempted if intubation was easy at the initial operation. Hypotension may follow induction, and laryngoscopy may be difficult in torrential haemorrhage.

See also, Ear, nose and throat surgery; Induction, rapid sequence

Topical anaesthesia. Application of local anaesthetic agent (e.g. cocaine, lidocaine, tetracaine) to skin or mucous membranes to produce anaesthesia. Used on the skin, conjunctiva, nasal passages, larynx and pharynx, tracheobronchial tree, rectum and urethra. Local anaesthetic has also been instilled into the bladder, pleural cavity, peritoneal cavity and synovial fluid of joints.

May be applied via direct instillation, soaked swabs, pastes/ointments or sprays. Systemic absorption may be rapid and the maximal safe doses should not be exceeded.

Torsade de pointes. Atypical VT characterised by polymorphic QRS complexes with repeated fluctuations of QRS axis, the complexes appearing to twist about the baseline (Fig. 156). Often associated with a prolonged Q–T interval. Initiated by a ventricular ectopic beat occurring during a prolonged pause after a previous ectopic.

electrolyte abnormalities, e.g. hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypocalcaemia.

electrolyte abnormalities, e.g. hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypocalcaemia.

drugs, e.g. class I antiarrhythmic drugs, tricyclic antidepressant drugs, phenothiazines.

drugs, e.g. class I antiarrhythmic drugs, tricyclic antidepressant drugs, phenothiazines.

congenital prolonged Q–T syndromes.

congenital prolonged Q–T syndromes.

increasing the heart rate, e.g. isoprenaline, cardiac pacing.

increasing the heart rate, e.g. isoprenaline, cardiac pacing.

Class I antiarrhythmic drugs should be avoided.

Fig. 156 Torsade de pointes

Total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA). Anaesthetic technique employing iv agents alone, and avoiding the use of inhalational agents. The patient breathes O2, air, or a mixture of the two. Drugs are given usually by infusion to achieve anaesthesia and appropriate analgesia. The drugs chosen are usually of short action and half-life to prevent accumulation and prolonged recovery. Examples include propofol, together with alfentanil, fentanyl or remifentanil. Ketamine has been used for its analgesic properties, e.g. together with midazolam. Neuroleptanaesthesia has also been used.

avoids unwanted effects of inhalational anaesthetic agents.

avoids unwanted effects of inhalational anaesthetic agents.

avoids pollution by gases and vapours.

avoids pollution by gases and vapours.

requires repeated injections or infusion devices.

requires repeated injections or infusion devices.

accurate prediction of plasma levels of anaesthetic agents is more difficult than with inhalational agents, because of the more complicated pharmacokinetics and the absence of actual measurements of drug concentration. Thus awareness or excessive dosage may occur unless one is familiar with the technique. Computer-assisted infusion has been employed to provide steady plasma levels according to pharmacokinetic data collected from hundreds of patients. Target-controlled infusion (TCI) devices employ similar data to run a special syringe driver according to the patient’s age, weight and desired plasma drug concentration, which are entered by the anaesthetist.

accurate prediction of plasma levels of anaesthetic agents is more difficult than with inhalational agents, because of the more complicated pharmacokinetics and the absence of actual measurements of drug concentration. Thus awareness or excessive dosage may occur unless one is familiar with the technique. Computer-assisted infusion has been employed to provide steady plasma levels according to pharmacokinetic data collected from hundreds of patients. Target-controlled infusion (TCI) devices employ similar data to run a special syringe driver according to the patient’s age, weight and desired plasma drug concentration, which are entered by the anaesthetist.

Total lung capacity. Volume of gas in the lungs after maximal inspiration. Normally approximately 6 litres. Determined by helium dilution (does not measure gas in poorly ventilated regions) or with the body plethysmograph.

Total parenteral nutrition, see Nutrition, total parenteral

Tourniquets. Used to reduce bleeding during limb surgery, and to allow IVRA. Inflated following exsanguination of the limb, e.g. by raising it for 2–3 min with the artery compressed, or by using a rubber Esmarch bandage. The latter increases CVP and may provoke cardiac failure in susceptible patients. It may also dislodge emboli from DVTs. Complications from tourniquets include: direct skin, muscle, nerve or vascular injury; reperfusion hyperaemia and limb oedema; and hypertension and tachycardia due to pain.

• Measures suggested to reduce compression and ischaemic injury:

Equipment should be checked before use. Tourniquets should not be used in sickle cell anaemia (avoidance in sickle trait has also been suggested). Protective padding is required under the tourniquet. Skin preparation solutions may cause chemical burns if allowed to soak into the padding.

[Johann FA von Esmarch (1823–1908), German surgeon]

Estebe JP, Davies JM, Richebe P (2011). Eur J Anaesthesiol; 28: 404–11

Toxic epidermal necrolysis, see Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome. Systemic illness associated with certain Staphylococcus aureus strains, thought to be caused by exotoxins (possibly with concurrent Gram-negative endotoxin production). Streptococci have also been implicated.

First described in 1978; the reported incidence increased around 1980, especially associated with menstruation and use of tampons. Features typically occur rapidly and include fever, hypotension, GIT upset, headache and myalgia. Generalised rash and/or oedema lead to desquamation 10–20 days later. MODS may occur. Treatment is supportive, with antibacterial drug therapy.

Trachea, see Tracheobronchial tree

Tracheal administration of drugs. Previously used when iv administration was not possible, e.g. cardiac arrest. Superseded by the intraosseous route in the emergency setting. Previously advocated at 2–3 times the iv dose, diluted in 10 ml saline; atropine, adrenaline and lidocaine were the drugs most commonly administered in this way. Many respiratory drugs are administered using inhalers and nebulisers.

Tracheal extubation, see Extubation, tracheal

Tracheal intubation, see Intubation, tracheal

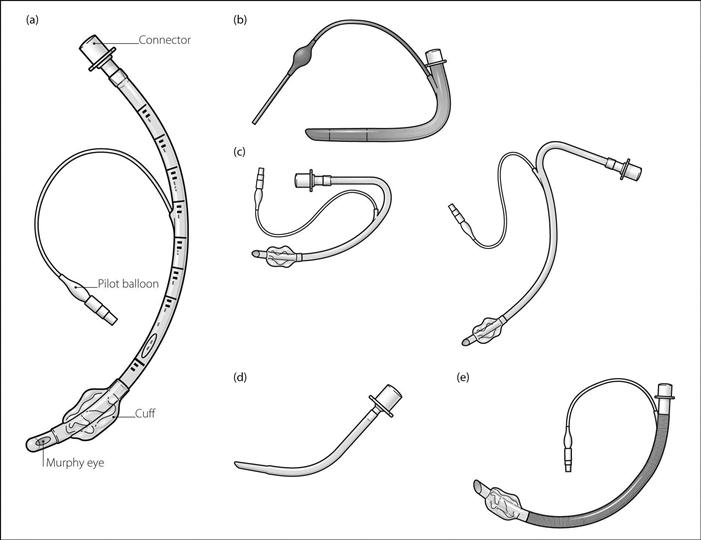

Tracheal tubes. Developed along with techniques for tracheal intubation. O’Dwyer described his intubating tube in 1885, although various tubes had been used previously, e.g. for CPR. The modern wide-bore tracheal tube was developed by Magill and Rowbotham after World War I, following the use of thin gum-elastic tubes for insufflation techniques. Separate tubes were placed into the trachea for delivery and removal of gases; these were eventually replaced by a single rubber (‘Magill’) tube. Cuffs were introduced by Guedel in 1928. Red rubber tracheal tubes have largely been replaced by sterile disposable polyvinyl chloride tubes, since the former deteriorate on repeated sterilisation, are more costly to use, and are irritant to the respiratory mucosa. Plastic tubes soften as they warm, e.g. in the trachea, and may be vulnerable to kinking.

Size 9 mm and 8 mm internal diameter orotracheal tubes are often employed for men and women respectively; smaller tubes (e.g. 7 mm and 6 mm) are often used in the elective surgical setting since they are associated with a lower incidence of sore throat and hoarse voice. However, for emergency intubation and ICU admission, larger-bore tubes are preferred to facilitate tracheobronchial suctioning and fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Average suitable length is 22–25 cm for oral tubes, and 25–28 cm for nasal tubes (for sizes of tubes for children, see Paediatric anaesthesia).

• Features of ‘typical’ modern tracheal tubes (Fig. 157a):

marked with the following information:

marked with the following information:

– size (internal diameter in mm; the external diameter may be marked in smaller lettering).

A radio-opaque line is incorporated in most modern tubes, to aid detection on CXR.

attached to a tracheal tube connector at the proximal end.

attached to a tracheal tube connector at the proximal end.

may bear a cuff near the distal end, with a pilot balloon running towards the proximal end.

may bear a cuff near the distal end, with a pilot balloon running towards the proximal end.

• Other shapes and types of tubes (Fig. 157b–e):

Cole tube: used in neonates. Shouldered, with thickened walls to prevent kinking. Designed to minimise resistance to flow of gas by virtue of their wide proximal portion; however, they increase resistance by causing turbulence at the junction with the narrow portion. They also may cause damage to the larynx and trachea if the shoulder is forced too far distally. Their avoidance has therefore been repeatedly suggested.

Cole tube: used in neonates. Shouldered, with thickened walls to prevent kinking. Designed to minimise resistance to flow of gas by virtue of their wide proximal portion; however, they increase resistance by causing turbulence at the junction with the narrow portion. They also may cause damage to the larynx and trachea if the shoulder is forced too far distally. Their avoidance has therefore been repeatedly suggested.

reinforced tubes: resemble standard tubes but contain a spiral of metal or nylon in the tube wall. Used where kinking of the tube may otherwise occur, e.g. neurosurgery, maxillofacial surgery. Originally made of latex rubber, they are now commonly made of plastic. They cannot be cut to size. Available with or without cuffs. The silicone tube supplied with the intubating LMA is reinforced and has a tapered tip, making it easier to pass through the device without catching on the vocal cords or arytenoids. This tube is also easier to railroad over a fibreoptic scope than standard tracheal tubes.

reinforced tubes: resemble standard tubes but contain a spiral of metal or nylon in the tube wall. Used where kinking of the tube may otherwise occur, e.g. neurosurgery, maxillofacial surgery. Originally made of latex rubber, they are now commonly made of plastic. They cannot be cut to size. Available with or without cuffs. The silicone tube supplied with the intubating LMA is reinforced and has a tapered tip, making it easier to pass through the device without catching on the vocal cords or arytenoids. This tube is also easier to railroad over a fibreoptic scope than standard tracheal tubes.

Tubes may bear an extra channel for sampling of distal gases or for jet ventilation. A directional tube has also been described, in which traction on a ring at the proximal end flexes the distal end, aiding placement during tracheal intubation. Laser-protected tubes include tubes made totally out of metal and those coated with ‘laser-proof’ substances.

See also, Endobronchial tubes; Intubation, tracheal; Tracheostomy

hypoxaemia: may be related to rapid removal of airway gases, causing atelectasis, bronchospasm/coughing or disconnection from the ventilator. Particularly likely if the patient is PEEP-dependent. Reduced by preoxygenation before and after suctioning, limitation of catheter size and use of self-contained suction catheters within the breathing system that avoid the need for disconnection.

hypoxaemia: may be related to rapid removal of airway gases, causing atelectasis, bronchospasm/coughing or disconnection from the ventilator. Particularly likely if the patient is PEEP-dependent. Reduced by preoxygenation before and after suctioning, limitation of catheter size and use of self-contained suction catheters within the breathing system that avoid the need for disconnection.

cross-infection/dispersal of infected material: reduced by sterile technique and self-contained suction equipment incorporating a catheter within the breathing tubing.

cross-infection/dispersal of infected material: reduced by sterile technique and self-contained suction equipment incorporating a catheter within the breathing tubing.

arrhythmias: may be related to hypoxaemia. Sinus bradycardia is especially common, via vagal stimulation.

arrhythmias: may be related to hypoxaemia. Sinus bradycardia is especially common, via vagal stimulation.

increased ICP: especially detrimental in patients with pre-existing raised ICP. May be reduced by increased sedation.

increased ICP: especially detrimental in patients with pre-existing raised ICP. May be reduced by increased sedation.

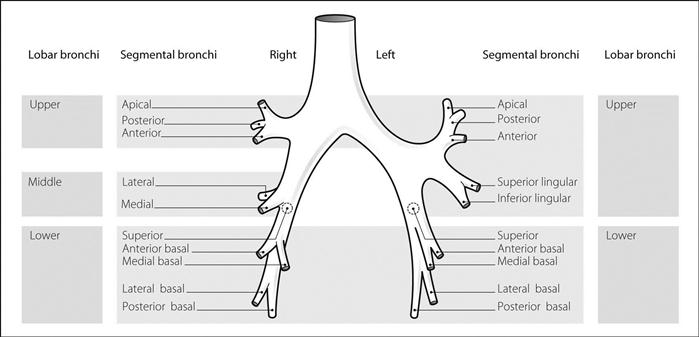

Tracheobronchial tree. Branching system consisting of 23 generations of passages from trachea to alveoli, comprising:

conducting airways: make up anatomical dead space:

conducting airways: make up anatomical dead space:

– trachea (generation 0): 10 cm long and 2 cm wide in the adult. Descends from the larynx level with C6, passing through the neck and thorax to its bifurcation level with T4–5 (at the level of the angle of Louis). Its walls are formed of fibrous tissue reinforced by 15–20 U-shaped cartilaginous rings (deficient posteriorly), united behind by fibrous tissue and smooth muscle. Lined with ciliated epithelium.

Relations: lies anterior to the oesophagus, with the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerves in the grooves between them. In the neck (see Fig. 113; Neck, cross-sectional anatomy) it is crossed anteriorly by the isthmus of the thyroid gland. Laterally lie the lateral lobes of the thyroid, the inferior thyroid artery and carotid sheath (containing the internal jugular vein, common carotid artery and vagus nerve). In the thorax (see Fig. 104b; Mediastinum) it is crossed anteriorly by the brachiocephalic artery and left brachiocephalic vein. On the left lie the common carotid and subclavian arteries above, and the aorta below. On the right lie the mediastinal pleura, right vagus nerve and azygous vein.

– right and left main bronchi (generation 1): arise at T4–5:

– lobar and segmental bronchi (generations 2–4) (Fig. 158).

Fig. 158 Lobar and segmental bronchi

– small bronchi to terminal bronchioles (generations 5–16).

– respiratory bronchioles (generations 17–19): bear occasional alveoli.

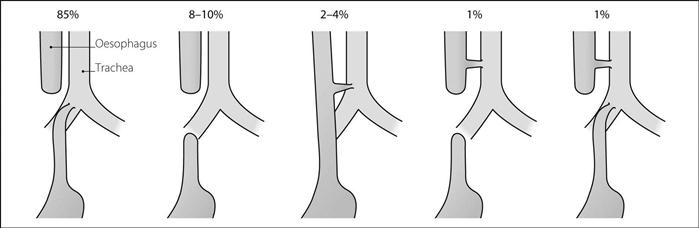

Tracheo-oesophageal fistula (TOF). Oesophageal atresia occurs in 1:3000 births, with TOF in 25% of cases. Different forms exist (Fig. 159). Babies may be premature and have other congenital abnormalities. TOF may present with choking during feeds, production of copious frothy mucus from the mouth or repeated chest infections following pulmonary aspiration. It is diagnosed by passing a radio-opaque nasogastric tube into the blind pouch; contrast medium is avoided because of risk of aspiration. Treated by surgery, performed thorascopically or via right thoracotomy. Primary anastomosis of the oesophagus is performed if possible.

• Anaesthesia is as for paediatric anaesthesia. In particular:

– correction of electrolyte abnormalities.

– traditionally, tracheal intubation is performed awake, avoiding IPPV by facemask to prevent gastric inflation. Intubation of the fistula may occur; if this happens the tracheal tube may be withdrawn and reinserted with the bevel direction altered. Positioning of the tip of the tube distal to the fistula prevents gastric inflation; this may be achieved by deliberate endobronchial intubation, followed by careful withdrawal of the tracheal tube until breath sounds are heard on both sides of the chest.

Tracheostomy. First performed in the 1700s for upper airway obstruction. Modern indications:

prophylactic or therapeutic relief of airway obstruction.

prophylactic or therapeutic relief of airway obstruction.

to protect the tracheobronchial tree against aspiration of food, saliva, etc., when pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes are obtunded, e.g. neurological disease.

to protect the tracheobronchial tree against aspiration of food, saliva, etc., when pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes are obtunded, e.g. neurological disease.

to allow suction and removal of secretions.

to allow suction and removal of secretions.

prolonged IPPV in ICU. Advantages over conventional tracheal intubation include easier nursing management, improved patient comfort (and therefore reduced sedation requirements), potential for eating and speaking, decreased incidence of sinusitis, and possibly assistance of weaning by a 30–50% reduction in dead space.

prolonged IPPV in ICU. Advantages over conventional tracheal intubation include easier nursing management, improved patient comfort (and therefore reduced sedation requirements), potential for eating and speaking, decreased incidence of sinusitis, and possibly assistance of weaning by a 30–50% reduction in dead space.

Increasingly, surgical tracheostomy is being replaced by the percutaneous procedure, especially in critically ill patients receiving IPPV (see Tracheostomy, percutaneous).

cuffed: plastic, with low-pressure, high-volume cuffs to minimise tracheal mucosal damage. The cuff may be deflated and the tube occluded with a finger during expiration, to allow speech. Cuffed tubes may also be fenestrated. Some incorporate a separate catheter opening just above the cuff, through which O2 may be diverted using a manual control to allow speech. The catheter may also be used for suction.

cuffed: plastic, with low-pressure, high-volume cuffs to minimise tracheal mucosal damage. The cuff may be deflated and the tube occluded with a finger during expiration, to allow speech. Cuffed tubes may also be fenestrated. Some incorporate a separate catheter opening just above the cuff, through which O2 may be diverted using a manual control to allow speech. The catheter may also be used for suction.

• Complications may be early or late:

– haemorrhage, especially from branches of the anterior jugular veins or thyroid isthmus.

– displacement of the tube: extrusion or endobronchial intubation.

– blockage, e.g. by secretions, compression by the cuff or occlusion against the carina.

– pneumothorax.

– infection, including superficial wound infection, tracheitis and chest infection.

– tracheal erosion and ulceration, e.g. into blood vessels, oesophagus.

– tracheal dilatation may occur.

humidification: vital to reduce risk of obstruction by viscous secretions.

humidification: vital to reduce risk of obstruction by viscous secretions.

tracheobronchial suctioning: sterile technique is mandatory. The suction catheter’s diameter should not exceed half that of the tracheostomy tube. Suction is applied on withdrawal, not insertion, of the catheter.

tracheobronchial suctioning: sterile technique is mandatory. The suction catheter’s diameter should not exceed half that of the tracheostomy tube. Suction is applied on withdrawal, not insertion, of the catheter.

daily cleaning and dressing to reduce risk of infection.

daily cleaning and dressing to reduce risk of infection.

Mallick A, Bodenham AR (2010). Eur J Anaesthesiol; 27: 676–82

Tracheostomy, percutaneous. Increasingly used in critically ill patients requiring tracheostomy instead of the traditional open procedure because of the following advantages:

Avoided in children and in the presence of coagulopathy, localised infection and difficult anatomy.

• Methods:

initial preparation and positioning as for the open procedure.

initial preparation and positioning as for the open procedure.

the cannula is left in the trachea, a wire advanced through it and the cannula withdrawn.

the cannula is left in the trachea, a wire advanced through it and the cannula withdrawn.

[Pasquale Ciaglia (1912–2000), US thoracic surgeon; Bill Griggs, Australian intensivist]

Cabrini L, Monti G, Landoni G, et al (2012). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand; 56: 270–81

Train-of-four nerve stimulation, see Neuromuscular blockade monitoring

Tramadol hydrochloride. Opioid analgesic drug, introduced in the UK in 1994. A pure agonist at mu opioid receptors, it is also a delta and kappa receptor agonist; it also inhibits noradrenaline uptake and enhances 5-HT release. Undergoes hepatic and renal elimination; contraindicated in patients with end-stage renal failure. Half-life is about 6 h. Administration with morphine was previously suggested to reduce the efficacy of both (i.e. an infra-additive effect); however, this is disputed, and several studies demonstrate that tramadol improves analgesia and reduces morphine requirements after major surgery.

• Dosage:

50–100 mg orally 4–6-hourly up to 400 mg/day for short courses. A slow-release formulation is available: 100–200 mg od/bd. A combined preparation with paracetamol is also available (37.5 mg tramadol with 325 mg paracetamol): 1–2 tablets qds.

50–100 mg orally 4–6-hourly up to 400 mg/day for short courses. A slow-release formulation is available: 100–200 mg od/bd. A combined preparation with paracetamol is also available (37.5 mg tramadol with 325 mg paracetamol): 1–2 tablets qds.

• Side effects: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, dry mouth, sweating, confusion and hallucinations, respiratory depression, sedation (the latter two less commonly than with morphine). Drug dependence and withdrawal have been reported, especially following prolonged treatment. Convulsions have been reported, especially in combination with other drugs known to reduce seizure threshold, e.g. tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Contraindicated in patients receiving monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Analgesic efficacy is reduced by concurrent administration of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (e.g. ondansetron).

Tranexamic acid. Antifibrinolytic drug, used to reduce bleeding, e.g. in trauma, cardiac surgery, prostatectomy, menorrhagia or dental extraction in haemophiliacs; it has also been used in streptokinase overdose and hereditary angioneurotic oedema.

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD). Application of ultrasound to demonstrate cerebral vessels. A low-frequency (2 MHz) pulse range-gated ultrasound beam is directed through the thin-boned transtemporal window; this allows assessment of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries of the cerebral circulation. Using the Doppler effect, flow velocities within these vessels can be determined. Uses include the detection of cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage, assessment of cerebral blood flow (e.g. in head injury, carotid endarterectomy) and the detection of air embolism. Has also been used to assess cerebral autoregulation.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Stimulation of peripheral nerves via cutaneous electrodes, to relieve pain. Based on the gate control theory of pain transmission; i.e. stimulation of Aβ fibres (by high-frequency TENS) and Aδ fibres (by low-frequency TENS) inhibits pain transmission by C fibres. Current is provided by a battery-powered pulse generator, which typically delivers a range of currents (0–50 mA), frequencies (0–200 Hz) and pulse widths (0.1–0.5 ms). Rectangular pulses are usually employed. Surface electrodes are usually carbon-impregnated silicone rubber.

Has been used successfully in acute pain (e.g. for fractured ribs, labour, postoperatively), but is usually employed for chronic pain management (peripheral nerve disorders, spinal cord and root disorders, muscle pain and joint pain). Efficacy is difficult to assess as there is significant placebo effect, but TENS may reduce analgesic requirements.

Allergic dermatitis at electrode sites may occur. Contraindicated in patients with pacemakers.

Transducers. Devices that convert one form of energy to another, usually to electricity in monitoring systems.

• May be:

passive: involving changes in:

passive: involving changes in:

– resistance, e.g. strain gauge, thermistor, photoresistor.

– inductance, e.g. pressure transducers.

– capacitance, e.g. condenser microphone.

active, i.e. involving generation of potentials:

active, i.e. involving generation of potentials:

– piezoelectric effect: generation of voltage across the faces of a quartz crystal when deformed.

See also, Arterial blood pressure measurement; Damping; pH measurement; Pressure measurement; Temperature measurement

Transfer factor, see Diffusing capacity

Transfusion, see Blood transfusion

Transfusion-related acute lung injury, see Blood transfusion

Transient radicular irritation syndrome (Transient neurologic syndrome). Pain and dysaesthesia in the buttock, thighs or calves following spinal anaesthesia; usually occurs within 24 h of the block and typically resolves within 72 h. Particularly associated with the use of lidocaine in hyperbaric solutions of higher concentrations (2.5–5%), and very narrow-gauge needles or microcatheters, which result in pooling of the drug around nerve roots. The lithotomy position has also been implicated, via stretching of the lumbosacral nerve roots and increasing their vulnerability. The syndrome may reflect a transient form of cauda equina syndrome following continuous spinal anaesthesia.

Zaric D, Pace NL (2009). Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2: CD003006