29 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Clinical Presentation

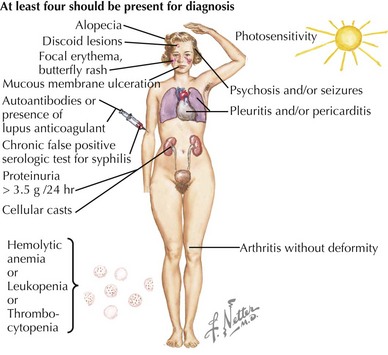

SLE is rare in children younger than age 5 years and is uncommon before adolescence. In childhood, girls are affected approximately four times more often than boys. The presenting symptoms are widely variable. Constitutional signs and symptoms, including fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and weight loss, are commonly seen. The most frequently involved specific sites affected by SLE are the skin, joints, and kidneys. Symptoms often precede the diagnosis by several months and may be insidious or acute in onset. The American College of Rheumatology provides criteria which are used clinically to aid in the diagnosis of SLE (Table 29-1, Figure 29-1). The diagnosis of SLE is made if at least four of the criteria are present or have been present in the past without another diagnosis that explains the findings. The antinuclear antibody (ANA), one of the criteria for diagnosis of SLE, is not a useful general screening test for rheumatologic disease and should not be sent routinely in the absence of other criteria for SLE.

Table 29-1 American College of Rheumatology 1997 Revised Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

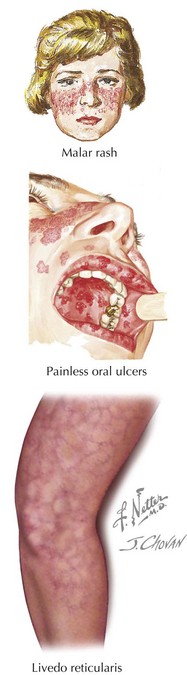

| Malar rash | “Butterfly” erythematous rash over malar eminences; spares nasolabial folds (see Figure 29-2) |

| Discoid rash | Raised erythematous patches with scaling and follicular plugging on the face, scalp, and extremities; may lead to scarring |

| Photosensitivity | Any rash that occurs as an unusual reaction to sunlight |

| Oral or nasal ulcerations | Painless ulcerations of the oral or nasal mucosa (see Figure 29-2) |

| Arthritis | Nonerosive arthritis of two or more peripheral joints |

| Nephritis | Persistent proteinuria >0.5 g/d or cellular casts (red blood cell, hemoglobin, granular, tubular, or mixed) |

| Serositis | Pleuritis or pericarditis |

| Neurologic disorder | Seizures or psychosis (in the absence of offending drugs or metabolic disturbances) |

| Cytopenia | Hemolytic anemia with reticulocytosis or leukopenia (<4000/mm3) or lymphopenia (<1500/mm3) or thrombocytopenia (<100,000/mm3) |

| Positive immunoserology | Antibodies to dsDNA or antibodies to Sm nuclear antigen or anticardiolipin antibodies or presence of lupus anticoagulant or false-positive serologic test for syphilis (known to be positive for ≥6 months and confirmed by Treponema pallidum immobilization or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test) |

| Positive antinuclear antibody | Abnormal titer of antinuclear antibodies at any point in time |

Adapted from Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40(9):1725, 1997.

Skin and Mucus Membrane Manifestations

There are four skin and mucocutaneous criteria: malar rash, discoid rash, oral or nasal ulcers, and photosensitivity. The malar rash, or classic “butterfly rash,” is typically maculopapular and photosensitive. Additionally, it classically extends across the nasal bridge, spares the nasolabial folds, and is nonscarring (Figure 29-2). Depending on the race of the child, it may be either hyper- or hypopigmented. A discoid rash is less common. These inflammatory lesions are coin shaped, raised, and erythematous. They are most commonly located on the face (especially the ears), scalp, and extremities. These lesions are scarring and lead to permanent alopecia when they occur on the scalp. The oral and nasal ulcers associated with SLE are usually painless; oral ulcers are classically located on the hard palate (see Figure 29-2). Other common skin manifestations include livedo reticularis (see Figure 29-2), alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon (see Figure 27-2), and digital ulcerations.

Renal Manifestations

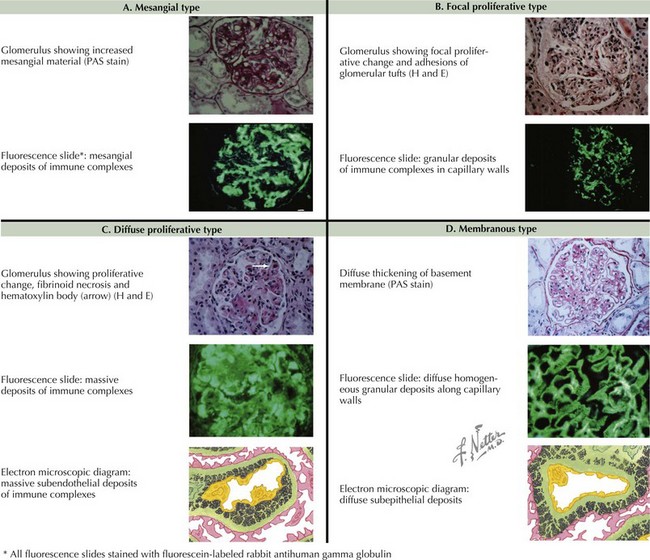

Renal disease is present in a majority of pediatric SLE and is a strong determinant of long-term prognosis. Its severity ranges from microscopic hematuria to chronic renal failure. Lupus nephritis usually develops within 2 years of diagnosis (see Chapter 62). SLE patients with significant proteinuria or abnormal renal function should undergo renal biopsy to classify their degree of renal involvement to aid in treatment decision making. The classification of lupus nephritis includes six classes, ranging from minimal mesangial involvement to diffuse involvement and glomerulosclerosis (Figure 29-3).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of SLE is broad and includes acute and chronic diseases that affect many organ systems (Box 29-1). Broad categories most important to consider include infectious, oncologic, rheumatic, and drug-induced causes.

Morbidity and Mortality

The morbidity and mortality attributed to renal disease is related to the histology of the lupus nephritis seen on the kidney biopsy (Figure 29-3). End-stage renal disease is most strongly associated with focal lupus nephritis (class III) and diffuse lupus nephritis (class IV). The most frequent cause of death for children with SLE is infection. Factors including leukopenia, hypocomplementemia, and immunosuppressive therapy contribute to an immunocompromised state that can result in death if a serious infection is not recognized.

Evaluation and Management

The diagnosis of SLE is established using the classification criteria, with consideration of important possibilities in the differential diagnosis based on the presenting signs and symptoms (see Table 29-1). In addition to the laboratory evaluation necessary to determine the criteria met by the patient, several other laboratory studies should be considered as part of the evaluation of a child with suspected SLE. Inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP] and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) are helpful as a general screen of the degree of inflammation present. Classically, the ESR is markedly elevated, and the CRP is normal or mildly elevated in patients with SLE. Complement levels (C3, C4) are decreased when active nephritis is present. The partial thromboplastin time (PTT) is prolonged when the lupus anticoagulant is present. Despite the prolongation of the PTT in the laboratory, the lupus anticoagulant leads to a hypercoagulable state clinically as described above. A complete urinalysis should be performed in all SLE patients. If proteinuria is present, a first-morning urine protein to creatinine ratio and a 24-hour urine collection should follow. If proteinuria is significant (>1 g/24 h), then a renal biopsy is warranted before therapy initiation to stage the lupus nephritis and aid in treatment decision making. It is also recommended that children with a new diagnosis have a baseline electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and chest radiograph.

Ginzler EM, Dooley MA, Aranow C, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous cyclophosphamide for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(21):2219-2228.

Macdermott EJ, Adams A, Lehman TJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus in children: current and emerging therapies. Lupus. 2007;16(8):677-683.

Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):929-939.