Systemic Illnesses Involving the Gastrointestinal Tract

David N.B. Lewin

Introduction

Systemic illnesses commonly affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI symptoms and morphologic changes can result from several different pathogenetic mechanisms, such as nonspecific or constitutional symptoms, pathologic changes common to intestinal and extraintestinal organs, secondary changes such as opportunistic infections or drug reactions, and metastatic disease. This chapter focuses on morphologic alterations in the GI tract resulting from disorders that primarily affect other organ systems.

Cardiovascular Disorders

Cardiac Surgery and Heart Transplantation

GI complications after open heart surgery are uncommon, occurring in approximately 1% of cases; however, the mortality rate is high (approximately 30%).1,2 Clinical features typically consist of GI hemorrhage secondary to stress ulceration, vascular insufficiency with ischemic necrosis of bowel, and acute diverticulitis. Additional risk factors for ischemia include end-stage renal disease, female sex, non–coronary artery bypass graft, and long pump times.2

In contrast to GI complications after open heart surgery, GI complications after cardiac transplantation have been reported in as many as 20% of patients.3,4 Complications include all of the hemorrhagic conditions mentioned previously. In addition, the use of steroids and immunosuppressive agents increases the risks of intestinal perforation, fistula formation, and infectious GI diseases. These patients are also at risk for posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders5 (see Chapter 52).

Ischemic Disease

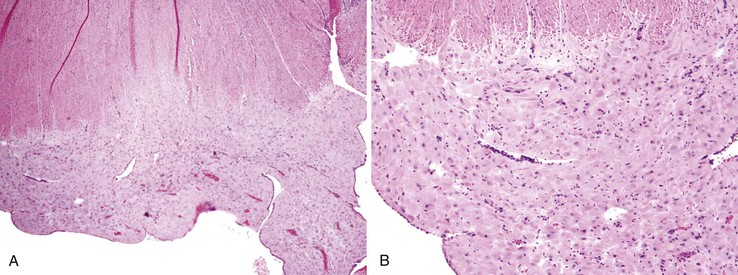

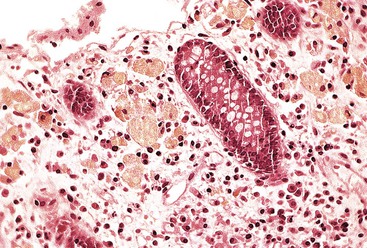

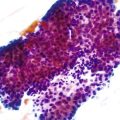

Intestinal ischemic disease can be divided into two major subsets: nonthrombotic (approximately 60% of cases) and thrombotic (approximately 40% of cases).6 Nonthrombotic causes of ischemic disease include decreased mesenteric blood flow secondary to cardiac failure, shock, atherosclerotic vascular disease, disseminated intravascular coagulation, vasculitis, and fibromuscular dysplasia. Thrombotic causes can be divided into arterial embolism, arterial thrombosis, and venous thrombosis. These are a heterogeneous group of disorders usually seen in elderly individuals.7 Colonic ischemia, the most common disorder (typically nonthrombotic), has a favorable prognosis. Acute mesenteric ischemia, in contrast, has a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of only 50%.6 Histologically, resultant lesions range from epithelial and lymphocytic apoptosis8 to mucosal necrosis and transmural infarction of the bowel (Fig. 6.1). Specifics concerning histology and pathology are discussed in Chapter 10.

Dermatologic Disorders

Both the skin and the GI tract may become involved in a variety of disease processes. These lesions may be divided as follows:

1. Primary dermatologic disorders that also involve the GI tract (Box 6.1). These lesions are discussed in this section.

2. Systemic disorders involving both the skin and the GI tract (Box 6.2). These lesions are discussed in other areas of this chapter.

Bullous Diseases

The majority of primary dermatologic bullous disorders that involve the GI tract occur in conjunction with a skin disorder (excluding dermatitis herpetiformis). These diseases typically involve the upper portion of the esophagus. Patients are seen with symptoms of dysphagia and odynophagia. Histologically, the lesions in esophageal squamous mucosa appear similar to those in the skin. The key distinguishing morphologic features are the level of the plane of separation (vesicle formation), the type of inflammatory infiltrate, and the presence or absence of acantholysis.9 Because the bullae rarely remain intact, diagnosis of these lesions on GI biopsy specimens is challenging. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of appropriate clinical information combined with biopsies of the skin lesions. In the esophagus, lesions often rupture and produce erosions; occasionally, fibrosis and stricture formation are also seen.

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa, a group of more than 12 genetically determined disorders that involve all organs lined by squamous epithelium,10 is characterized by the formation of vesiculobullous lesions secondary to minor trauma. The site of cleavage can be in the dermis (dermolytic or dystrophic form), at the dermoepidermal junction (junctional form), or in the epidermis (epidermolytic or simplex form). Involvement of the GI tract occurs in 50% of patients with the dystrophic form and in 33% of those with the junctional or simplex form.11 Stricture and esophageal webs occur most frequently in the dystrophic form but can also be seen rarely in the junctional or simplex form.12 In addition, anal and perianal disease and perianal blistering are seen in all types. Histologically, this lesion is characterized by separation of the epithelium and formation of bullae, with little or no inflammatory infiltrate.

Epidermolysis bullosa aquisita is a rare acquired disorder with clinical characteristics similar to those of epidermolysis bullosa except for adult onset, milder skin disease, and lack of family history. It may be associated with systemic diseases such as amyloidosis, multiple myeloma, diabetes mellitus, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A subset of patients have circulating immunoglobulin G (IgG) that recognizes collagen IV. Endoscopic biopsy may show linear deposition of IgG in the basement membrane.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a bullous disorder that affects middle-aged and older individuals. The bullae are superficial and flaccid. The lesion is an intraepidermal bulla formed by acantholysis (loss of intracellular bridges). Histologically, the cells lose their normal angular contours and become rounded. Basal keratinocytes typically remain attached to the epidermal basement membrane. The inflammatory infiltrate is variable; eosinophils and lymphocytes are the cells most commonly present in the epidermis, both surrounding and within the bullae and within the subjacent lamina propria. Standard biopsy forceps may provide only superficial specimens that are inadequate for diagnosis.13 Direct immunofluorescence for immunoglobulins and complement component C3 is positive in the epidermal intercellular spaces.14 The incidence of esophageal involvement is unclear. Some studies report endoscopic lesions in as much as 80% of patients.15,16 In addition, immunofluorescence performed on esophageal mucosa is usually positive in all patients with active disease.17

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is a subepidermal bullous disorder characterized by large, tense blisters on the skin. Mucosal involvement of the GI tract is much less common than in pemphigus vulgaris,18 although one report described esophageal blisters in 4% of patients with typical bullous pemphigoid.19 The histology of the bullous lesion has not been described. However, linear deposits of IgG and complement in the basement membrane of the esophagus and occasionally in the stomach, similar to those found in the skin, have been described.18 A single case of bullae in the colon has also been reported.20

Cicatricial pemphigoid (benign mucous membrane pemphigoid) is an autoimmune bullous disease related to bullous pemphigoid. It has similar immunohistochemical linear deposition of C3 and IgG. The circulating autoantibodies recognize bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BPAC2). Esophageal involvement has been reported in approximately 4% of patients with the disease.21

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme, as the name implies, is a cutaneous reaction pattern characterized by a combination of skin and mucosal lesions. The mucosal lesions usually occur on the lips or in the oral cavity and conjunctiva. However, the esophagus and, rarely, other regions of the GI tract may be involved.22 Included in this group of disorders is the Stevens-Johnson syndrome (macular trunk lesions with mucosal involvement).23 Many of these lesions occur secondary to drug reactions (type IV hypersensitivity reactions) or, occasionally, reactions to infectious agents such as mycoplasmae. In the esophagus, lesions have been described as small white patches similar to those caused by Candida spp. infection. Histologically, superficial ulceration and marked intraepithelial lymphocytosis are often observed. Individual squamous cell necrosis most often involves the basal cells but may also include the entire thickness of the epithelium. Lesions typically regress; therefore, GI complications usually are not sampled for biopsy.

Hailey-Hailey and Darier Diseases

Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as benign familial pemphigus, is a rare disorder with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Patients typically are seen in the fourth to fifth decade of life with blistering and crusting skin lesions in intertriginous zones. Mucous membrane involvement is rare but may occur. Darier disease is similar to Hailey-Hailey disease, but its onset is typically in the first to second decade of life. Histologic features of both include dyskeratosis, suprabasal acantholysis, papillomatosis, and suprabasal separation with loss of intracellular bridges. Darier disease more commonly involves the esophagus.24

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a pruritic vesicular dermatitis with a symmetric distribution on the skin. Unlike the previously discussed bullous disorders of the skin, this disease does not produce bullous lesions in the GI tract. Dermatitis herpetiformis is strongly associated with celiac disease. Approximately 70% of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis show evidence of villous atrophy on small bowel biopsy.25 However, most patients are asymptomatic. Of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis, 90% are positive for endomysial autoantibodies26 (typically seen with celiac sprue as well). Human leukocyte antigen associations are similar for both dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac sprue. Both the skin disease and the GI symptoms can be controlled by a gluten-free diet.27

Dermatogenic Enteropathy

Many GI symptoms and histologic findings have been described in patients with active psoriasis and eczema. Steatorrhea and malabsorption are not uncommon, and the terms dermatogenic enteropathy and psoriatic enteropathy have been applied to these syndromes.28,29 Histologically, the duodenal mucosa shows an increase in the numbers of mast cells and eosinophils. A subset of patients have increased numbers of duodenal intraepithelial lymphocytes and antibodies to gliadin (suggestive of latent celiac sprue).30 In addition, the colon may show increased lamina propria cellularity, active inflammation, and occasional gland atrophy in mucosal biopsy specimens from patients who have psoriasis without bowel symptoms.31

Dermatologic Disorders Associated with Malignancies of the GI Tract

Acanthosis Nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans consists of numerous brown, hyperpigmented, velvety skin plaques located in the axillae, groin, and flexural areas. The lesion has two major forms—one associated with internal malignancies and the other associated with insulin resistance. Microscopically, dermal lesions are characterized by diffuse hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. Epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus also has been described.

When present, this lesion is usually associated with adenocarcinomas of the stomach and colon. At least one report has suggested that it is caused by the production of transforming growth factor-α by tumor cells.32

Tylosis

Focal nonepidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (tylosis) is a rare, autosomal dominant, inherited defect of keratinization. It is strongly associated with the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, with tumors appearing in 95% of patients.33 The skin lesion is characterized by thickening of the stratum corneum of the palms and soles. The esophageal mucosa in tylosis is typically affected by papillomatosis, which appears as multiple small protrusions, some with spines due to acanthosis. Molecular studies have mapped the defective gene to a small region on chromosome 17q25.34,35 The same region has been implicated in the development of sporadic squamous cell carcinoma and Barrett esophagus–associated adenocarcinoma.

Endocrine Disorders

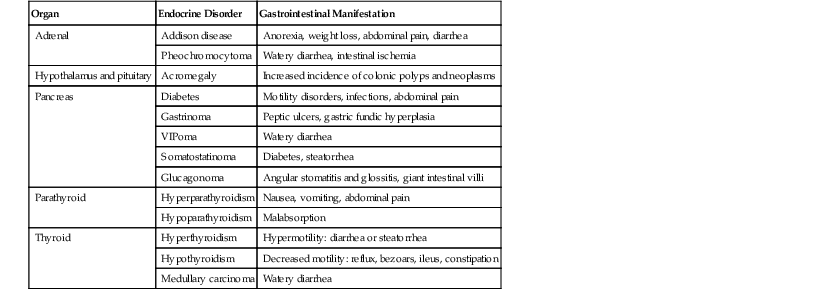

Alterations in the secretion of endocrine hormones in endocrine disorders may have a variety of GI effects. Most of these produce functional GI symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain secondary to changes in GI motility (Table 6.1). Most of these diseases do not cause significant morphologic or histologic abnormalities and are described only briefly here.

Table 6.1

Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Endocrine Disorders

| Organ | Endocrine Disorder | Gastrointestinal Manifestation |

| Adrenal | Addison disease | Anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea |

| Pheochromocytoma | Watery diarrhea, intestinal ischemia | |

| Hypothalamus and pituitary | Acromegaly | Increased incidence of colonic polyps and neoplasms |

| Pancreas | Diabetes | Motility disorders, infections, abdominal pain |

| Gastrinoma | Peptic ulcers, gastric fundic hyperplasia | |

| VIPoma | Watery diarrhea | |

| Somatostatinoma | Diabetes, steatorrhea | |

| Glucagonoma | Angular stomatitis and glossitis, giant intestinal villi | |

| Parathyroid | Hyperparathyroidism | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain |

| Hypoparathyroidism | Malabsorption | |

| Thyroid | Hyperthyroidism | Hypermotility: diarrhea or steatorrhea |

| Hypothyroidism | Decreased motility: reflux, bezoars, ileus, constipation | |

| Medullary carcinoma | Watery diarrhea |

VIP, Vasoactive intestinal peptide.

Adrenal Gland

Addison disease (primary chronic adrenocortical insufficiency) may cause common GI disturbances such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.38 Pheochromocytomas are characterized by hypertension due to high catecholamine levels. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction, megacolon, and even bowel ischemia have also been described and are thought to be secondary to the vasoconstrictive action of excess catecholamine levels.39

Hypothalamus and Pituitary

The hypothalamus and pituitary function as a unit. Disorders of either one infrequently affect the GI tract. Hypopituitarism affects intestinal motility, as does hypothyroidism. Pituitary adenomas are part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome, discussed later in this chapter. Of the hyperpituitary lesions, acromegaly is of interest with respect to GI neoplasia. Acromegaly is characterized by chronic hypersecretion of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor, usually due to a pituitary adenoma. It is associated with overgrowth of the musculoskeletal system and all organs, including the GI tract. Acromegaly has been shown to increase epithelial cell proliferation in the colon,40 and an increased prevalence of colonic adenomas and colonic carcinoma has been observed.41 An increased risk of gastric carcinoma has also been suggested but is less well established.42

Pancreas

Diseases of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas commonly affect the GI tract. These include pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, diabetes, and hormonal effects of functional pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency typically gives rise to steatorrhea and malabsorption and is discussed further in Chapter 39.

Diabetes can involve significant GI symptoms.43 These result from decreased motility secondary to autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Patients have symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. Abdominal bloating appears to correlate best with decreased gastric emptying.44 The delayed gastric emptying associated with gastric atony and gastric dilation is called gastroparesis diabeticorum, and an increased risk of bezoar formation is apparent. Patients can also experience periodic intractable diarrhea and crampy abdominal pain. Because of hypomotility, these patients are at risk for bacterial infection and malabsorption. Patients are also at increased risk for Candida infection of the esophagus.45 Histologic features are nonspecific. Neuropathic findings with silver stains have been described,46 as have periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive vascular deposits in the vessels of the submucosa.47

Excess hormonal production from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans can be a result of diffuse hyperplasia (nesidioblastosis) or pancreatic endocrine tumors. Many hormones, such as insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, gastrin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, calcitonin, parathormone, and serotonin, can be produced by these lesions. All GI manifestations reflect altered digestive function and motility.48

Parathyroid

Both hyperparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism can cause GI symptoms. GI symptoms occur in half of patients with hyperparathyroidism and may be the presenting symptom in 15% of cases.49 These patients typically have abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Many of these symptoms are thought to be due to hypercalcemia, which results in altered neuronal transmission and neuromuscular excitability.50 Hypoparathyroidism can be associated with malabsorption and steatorrhea. The small intestinal mucosa is typically histologically normal, but rare associations with celiac sprue have been reported.51

Thyroid

Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can cause GI symptoms. Hyperthyroidism produces hypermotility of the gut, and hypothyroidism causes hypomotility. Hyperthyroidism can result in rapid gastric emptying, watery diarrhea, and steatorrhea.52 No constant structural changes in the mucosa or in the wall of the bowel have been consistently reported. Hypothyroidism can be associated with gastric bezoar formation, ileus, volvulus, constipation, and megacolon.52 In patients with marked myxedema, dilation and thickening of the bowel wall with microscopic accumulation of mucopolysaccharide substances in the submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa have been described.53

Thyroid neoplasms may also produce GI effects. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid is a tumor of the calcitonin-producing endocrine C cells of the thyroid. Patients may have prominent “explosive” watery diarrhea as the result of ectopic hormone production.54 Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid also can be associated with Gardner syndrome.55

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia

The MEN syndromes are a group of autosomal dominant inherited disorders associated with hyperplasia or neoplasms of several endocrine organs. Three main varieties of this syndrome can occur—MEN I, MEN IIa, and MEN IIb (or III). GI manifestations are caused by the products of endocrine proliferations.56 Each of these syndromes is associated with a mutant gene locus—MEN I with the MEN1 gene locus, and MEN IIa and IIb with the RET gene locus. MEN I is associated with pancreatic endocrine tumors (often gastrinomas) and with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which is associated with gastric and duodenal disease. MEN IIb may be associated with ganglioneuromatosis, ganglion cell hyperplasia, and hypertrophy of the plexuses of Meissner and Auerbach in the GI tract. Chronic constipation, diarrhea, or both may be associated with MEN IIb.57

Hematologic Disorders

Hemorrhagic Disorders

Patients with bleeding disorders may develop spontaneous hemorrhage in any part of the GI tract. Between 10% and 25% of patients with hemophilia suffer from GI hemorrhage.58 Von Willebrand disease,59 heparin or warfarin overdose, vitamin K deficiencies, platelet deficiency, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) can all result in hemorrhage of the GI tract. This is most commonly seen in the upper GI tract and typically is most prominent in the submucosa. It can be severe enough to involve the entire thickness of the bowel wall and give rise to an intramural hematoma.60 More severe lesions can cause luminal narrowing, rigidity with obstruction, and, rarely, intussusception.58

Thrombotic Disorders

Sickle cell anemia,61 polycythemia rubra vera,62 and other thrombotic disorders63 can produce thrombosis, leading to infarction and hemorrhage of the intestines. Sickle cell anemia causes sickling of red blood cells and hyperviscosity of the blood and typically produces arterial and capillary obstruction.61 It involves the watershed areas of the distal transverse colon and splenic flexure, which have the lowest oxygen tension. Sickled red blood cells may be found in the vessels. Polycythemia usually leads to venous obstruction of the portal and mesenteric veins. These lesions involve the deeper parts of the bowel wall, including the muscularis propria. Diagnosis is based on the finding of venous thrombi in the mesenteric and mesocolic tissues not in the field of infarction, which occur in conjunction with appropriate clinical history.

Megaloblastic Anemia

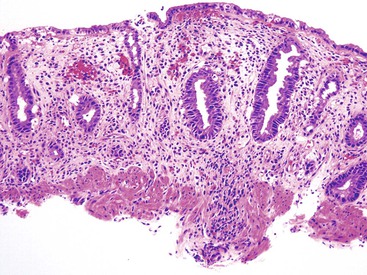

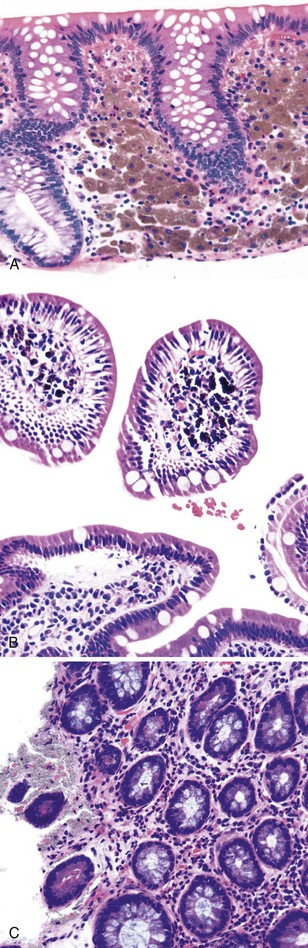

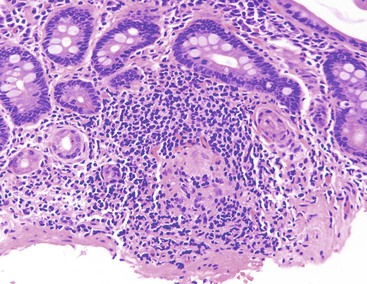

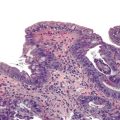

Megaloblastic anemias are associated with deficiencies of folic acid and vitamin B12. These anemias are characterized by megaloblastic proliferation of actively growing cells, as is typically described in bone marrow aspirations but is also seen in the epithelial cells of the GI tract. Owing to impaired DNA synthesis, actively dividing cells in the gastric pits, small bowel, and colonic crypts typically show enlarged, immature-appearing nuclei (Fig. 6.2). The nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio is decreased. The overall numbers of mitotic figures are also reduced. In addition, PAS-negative, Alcian blue–negative cytoplasmic vacuoles have been described in duodenal enterocytes.64 Megaloblastic anemia can be caused by pernicious anemia secondary to autoimmune gastritis; therefore, gastric findings of atrophic autoimmune gastritis may also be present.

Leukemia and Lymphoma

Involvement of the GI tract is often noted in patients with leukemia and lymphoma. This can occur directly by tumor (primary or secondary), secondary to complications of disease, or secondary to therapy (see Chapter 31 for details).

Autopsy studies have revealed GI involvement in 50% of patients with leukemia.65 In secondary involvement of the GI tract by either leukemia or lymphoma, tumor infiltrates are often multifocal and may be present anywhere from the esophagus to the rectum.66 These infiltrates can cause aphthous-type ulcers (typical of leukemic infiltrations) or can result in polypoid, masslike, or large ulcers (typical of lymphomatous involvement).67 The larger mass lesions can occasionally cause obstruction or intussusception.68 Histologic features are those typical of the particular type of leukemia or lymphoma. Malignant cells are typically found in the mucosal and submucosal tissue. Tissue should be collected for molecular and cytogenetic analysis, because many leukemias and lymphomas include diagnostic and clinically important changes.69 Primary lymphomas of the GI tract are often solitary lesions, although diffuse forms do occur (usually in the small bowel).

Secondary effects of tumor overgrowth, or of chemotherapy, resulting in decreased numbers of platelets and inflammatory cells can lead to hemorrhagic lesions of the GI tract and opportunistic infections. In addition, neutropenic colitis, which is a necrotizing inflammatory disorder of the colon that occurs in neutropenic patients, can occur with chemotherapy and, rarely, as a complication of acute leukemia.70 Finally, patients who have received a bone marrow transplant may develop graft-versus-host disease, which is characterized by apoptotic destruction of the epithelium throughout the GI tract. It typically manifests with diarrhea. Histologically, it is characterized by apoptosis of the epithelial cells, followed by crypt and gland loss and, ultimately, mucosal erosion and ulceration.71

Metabolic Disorders

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a systemic disorder that occurs secondary to zinc deficiency resulting from a congenital defect in absorption of dietary zinc. This disorder has been localized to a gene (SLC39A4) that codes for a transmembrane zinc uptake protein (hZIP4).72 It typically manifests after infancy and weaning (although rare cases have been described in adulthood73). It is characterized by chronic diarrhea associated with failure to thrive, periorofacial dermatitis, paronychia, nail dystrophy, alopecia, susceptibility to infection, and behavioral change. Serum zinc levels are typically decreased. Treatment is provided in the form of oral zinc. Mucosal biopsy of the small bowel can be normal or can show mild, patchy villous lesions. Abnormal inclusion bodies have been described in Paneth cells on electron microscopy.74 Acrodermatitis may also be caused by zinc deficiency secondary to Crohn’s disease75 or malnutrition.76

Plummer-Vinson Syndrome (Paterson–Brown Kelly Syndrome)

The unusual Plummer-Vinson syndrome has shown a recent decrease in incidence.77 It is characterized by iron deficiency (its presumed cause), dysphagia, and esophageal webs.78 Dermatologic findings of angular stomatitis, atrophic tongue, and brittle nails are also seen. Long-standing disease is associated with an increased incidence of postcricoid carcinoma. Iron repletion improves all lesions.

Vitamin Disorders

In general, vitamin disorders are not associated with specific GI symptoms or lesions. Exceptions are brown bowel syndrome, which is thought to be caused by a deficiency of vitamin E (discussed later), and pellagra, which is associated with niacin deficiency (discussed in this section). Multiple vitamin deficiencies are often noted in malabsorptive disorders. Vitamins, macronutrients, and minerals are thought to have a protective effect with respect to neoplasia of the GI tract, especially for esophageal79,80 and gastric81 malignancies. Deficiency in vitamin K or anticoagulation therapy leads to a decrease in coagulation factors and can result in hemorrhagic lesions throughout the body.82 In the GI tract, these range from focal petechial hemorrhages to frank exsanguination. No specific histologic features are associated with these lesions. Similarly, vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) can lead to hemorrhage and delayed wound healing. Deficiencies of folic acid and vitamin B12 are associated with megaloblastic anemia and megaloblastic changes in the epithelial cells of the stomach and small intestine.83 Olestra (a nonabsorbed fat replacement) may decrease the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.84

Pellagra

Pellagra is a vitamin deficiency that has major GI effects. It is caused by a deficiency of niacin, either dietary (deficiency found in developing countries, alcoholics, and the elderly) or secondary to impaired absorption (e.g., Crohn’s disease,85 amyloidosis86). It is characterized clinically by diarrhea, dermatitis, and dementia. Diarrhea is often bloody. However, patients can have steatorrhea.87 The vitamin deficiency interferes with the normal renewal of epithelial tissue; hence, the effects on the skin and GI tract. Endoscopically, approximately half of patients have lesions. However, all have microscopic inflammation. Endoscopic lesions range from redness and granularity to focal ulceration and more extensive confluent lesions. Microscopically, the inflammatory infiltrate is nonspecific. In the esophagus, mild to severe esophagitis is seen.88 The small bowel may be normal or may show mild villous blunting and increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria.89 In the large bowel, a mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrate with features of colitis cystica superficialis (cystic dilation of the crypts and crypt abscess formation) has been described. Patients usually respond to niacin replacement therapy.

Lipoprotein Disorders

Abetalipoproteinemia

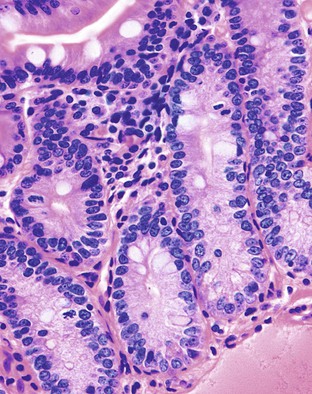

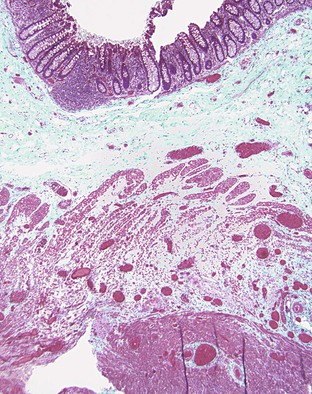

Abetalipoproteinemia (discussed further in Chapter 9) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a defect in the secretion of plasma lipoproteins that contain apolipoprotein B. Patients have steatorrhea, usually in infancy, with central nervous system symptoms such as disturbance in gait and balance and fatigue.90 On peripheral smear, acanthocytes are usually prominent (in 50% of red blood cells). Laboratory findings show an absence of very-low-density lipoproteins, the presence of chylomicrons, and a reduction in triglycerides and other lipids. The defect occurs in a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein required for the secretion of plasma lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B.91 Normal intraluminal digestion of lipids occurs, along with transport of triglycerides and monoglycerides and their reesterification in enterocytes. However, lipids cannot be excreted on the basal lateral membrane of the enterocytes into blood and lymphatics. Histologically, this translates into prominent accumulation of fine lipid droplets within the basal aspect of the enterocytes (Fig. 6.3). These can be stained with Oil Red O on frozen-section tissue or seen by electron microscopic examination. The overall architecture of the small bowel is normally well maintained. One pitfall in diagnosis is the similar appearance of lipid droplets identified in normal individuals after a recent lipid-rich meal; therefore, the diagnosis should be made only in fasting patients.

Tangier Disease

Tangier disease is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by deposition of cholesteryl esters in the reticuloendothelial system, almost complete absence of high-density lipoprotein in the plasma, and aberrant cellular lipid trafficking.92 Clinically, patients present with hepatosplenomegaly, enlarged tonsils, peripheral neuropathy, and, occasionally, diarrhea. Laboratory studies reveal low blood levels of high-density lipoprotein and cholesterol (due to lack of apoprotein A) and high levels of triglycerides. Endoscopically, the lesions are described as tiny yellow nodules or orange-brown spots.93 Microscopic examination reveals clusters of foamy histiocytes in the lamina propria (Fig. 6.4). Electron microscopic findings include intracytoplasmic vacuoles unbounded by membranes; these are often confluent in appearance94 (see Chapter 9 for details).

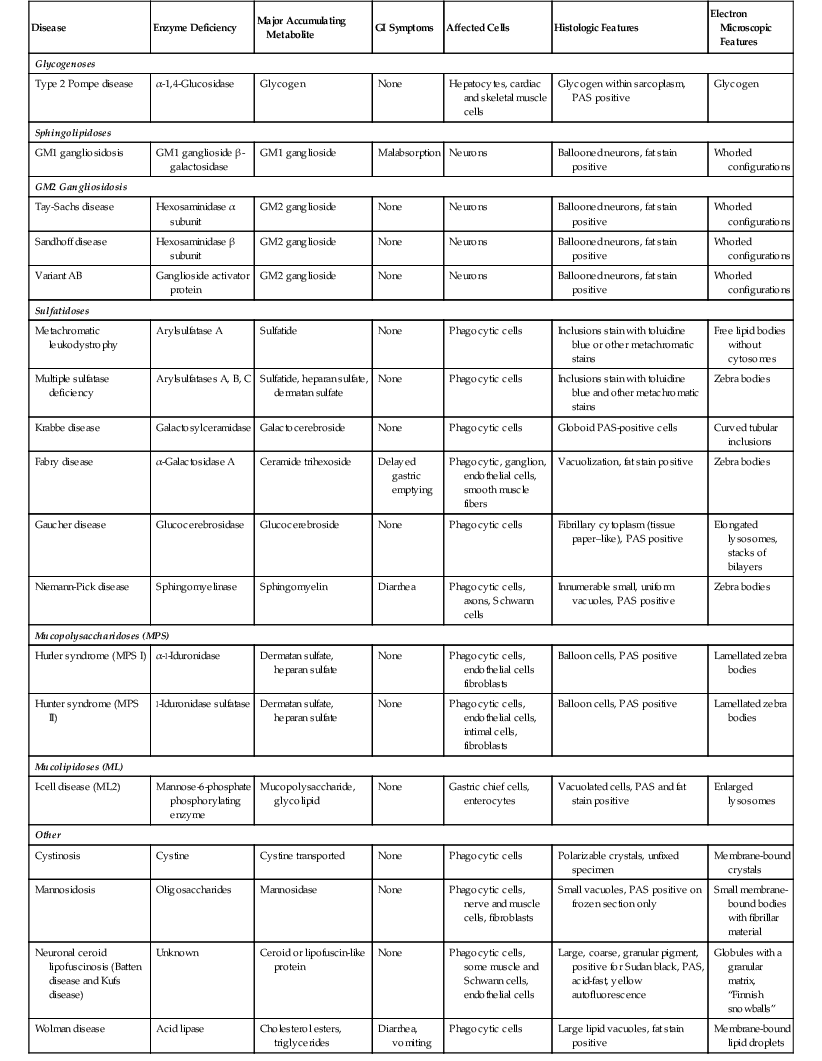

Lysosomal Storage Disorders

Lysosomes, which are a major component of the intracellular digestive tract, contain hydrolytic enzymes made in the endoplasmic reticulum. These enzymes break down a variety of complex macromolecules that are either a component of the cell or are taken up by phagocytosis. Lysosomal storage disorders are inherited disorders (usually autosomal recessive) caused by lack of a functional enzyme or defective enzyme lysosome targeting. Substances typically accumulate within cells at the site where most of the degraded material is found; degradation typically occurs at this location.

Storage disorders can be divided based on the biochemical nature of the accumulated metabolite into glycogenoses, sphingolipidoses (lipidoses), mucopolysaccharidoses, mucolipidoses, and others. Most of these diseases have prominent central or peripheral nervous system effects.95 Except for Fabry disease, they do not have significant GI effects. Case reports of malabsorption in GM1 gangliosidosis,96 diarrhea in Niemann-Pick disease,97 and diarrhea and vomiting in Wolman disease have been described.98

The importance of these diseases is that depositions can be identified in a variety of cells in the GI tract (Table 6.2), typically in the phagocytic cells (macrophages) in the lamina propria. The histologic appearance typically reveals an accumulation of cells with foamy cytoplasm. The material may be positive for fat stains such as Oil Red O or Sudan black on frozen-section tissue or PAS stain, depending on the particular substance that has accumulated. Electron microscopic examination typically reveals enlarged, unusually shaped lysosomes. Historically, many of these diagnoses have been made on rectal biopsy with histochemical stains and subsequent electron microscopic examination.99–101 This technique has largely been supplanted by specific enzyme content analysis of circulating lymphocytes or biopsy material. Differentiation among the common mimics of storage disorders is described in the next section.

Table 6.2

Lysosomal Storage Diseases

| Disease | Enzyme Deficiency | Major Accumulating Metabolite | GI Symptoms | Affected Cells | Histologic Features | Electron Microscopic Features |

| Glycogenoses | ||||||

| Type 2 Pompe disease | α-1,4-Glucosidase | Glycogen | None | Hepatocytes, cardiac and skeletal muscle cells | Glycogen within sarcoplasm, PAS positive | Glycogen |

| Sphingolipidoses | ||||||

| GM1 gangliosidosis | GM1 ganglioside β-galactosidase | GM1 ganglioside | Malabsorption | Neurons | Ballooned neurons, fat stain positive | Whorled configurations |

| GM2 Gangliosidosis | ||||||

| Tay-Sachs disease | Hexosaminidase α subunit | GM2 ganglioside | None | Neurons | Ballooned neurons, fat stain positive | Whorled configurations |

| Sandhoff disease | Hexosaminidase β subunit | GM2 ganglioside | None | Neurons | Ballooned neurons, fat stain positive | Whorled configurations |

| Variant AB | Ganglioside activator protein | GM2 ganglioside | None | Neurons | Ballooned neurons, fat stain positive | Whorled configurations |

| Sulfatidoses | ||||||

| Metachromatic leukodystrophy | Arylsulfatase A | Sulfatide | None | Phagocytic cells | Inclusions stain with toluidine blue or other metachromatic stains | Free lipid bodies without cytosomes |

| Multiple sulfatase deficiency | Arylsulfatases A, B, C | Sulfatide, heparan sulfate, dermatan sulfate | None | Phagocytic cells | Inclusions stain with toluidine blue and other metachromatic stains | Zebra bodies |

| Krabbe disease | Galactosylceramidase | Galactocerebroside | None | Phagocytic cells | Globoid PAS-positive cells | Curved tubular inclusions |

| Fabry disease | α-Galactosidase A | Ceramide trihexoside | Delayed gastric emptying | Phagocytic, ganglion, endothelial cells, smooth muscle fibers | Vacuolization, fat stain positive | Zebra bodies |

| Gaucher disease | Glucocerebrosidase | Glucocerebroside | None | Phagocytic cells | Fibrillary cytoplasm (tissue paper–like), PAS positive | Elongated lysosomes, stacks of bilayers |

| Niemann-Pick disease | Sphingomyelinase | Sphingomyelin | Diarrhea | Phagocytic cells, axons, Schwann cells | Innumerable small, uniform vacuoles, PAS positive | Zebra bodies |

| Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) | ||||||

| Hurler syndrome (MPS I) | α-l-Iduronidase | Dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | None | Phagocytic cells, endothelial cells fibroblasts | Balloon cells, PAS positive | Lamellated zebra bodies |

| Hunter syndrome (MPS II) | l-Iduronidase sulfatase | Dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate | None | Phagocytic cells, endothelial cells, intimal cells, fibroblasts | Balloon cells, PAS positive | Lamellated zebra bodies |

| Mucolipidoses (ML) | ||||||

| I-cell disease (ML2) | Mannose-6-phosphate phosphorylating enzyme | Mucopolysaccharide, glycolipid | None | Gastric chief cells, enterocytes | Vacuolated cells, PAS and fat stain positive | Enlarged lysosomes |

| Other | ||||||

| Cystinosis | Cystine | Cystine transported | None | Phagocytic cells | Polarizable crystals, unfixed specimen | Membrane-bound crystals |

| Mannosidosis | Oligosaccharides | Mannosidase | None | Phagocytic cells, nerve and muscle cells, fibroblasts | Small vacuoles, PAS positive on frozen section only | Small membrane-bound bodies with fibrillar material |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease and Kufs disease) | Unknown | Ceroid or lipofuscin-like protein | None | Phagocytic cells, some muscle and Schwann cells, endothelial cells | Large, coarse, granular pigment, positive for Sudan black, PAS, acid-fast, yellow autofluorescence | Globules with a granular matrix, “Finnish snowballs” |

| Wolman disease | Acid lipase | Cholesterol esters, triglycerides | Diarrhea, vomiting | Phagocytic cells | Large lipid vacuoles, fat stain positive | Membrane-bound lipid droplets |

GI, Gastrointestinal; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff stain.

Fabry Disease

Fabry disease is a rare, X-linked lipid storage disorder that is caused by a deficiency of lysosomal α-galactosidase A and results in cellular deposition of glycolipids in many tissues. Clinically, these patients have involvement of multiple organ systems. Symptoms include excruciating pain in the extremities (acroparesthesia), skin vessel ectasia (angiokeratoma), corneal and lenticular opacity, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and renal failure.102 GI symptoms are seen in 62% of male and 29% of female heterozygotes.103 Features include vascular ectasia,104 delayed gastric emptying,105 diarrhea, and, rarely, ischemic bowel disease with perforation.106 Histologically, glycolipid deposition is identified in vacuolated ganglion cells in the Meissner plexus and in small blood vessels. By electron microscopy, laminated and amorphous intralysosomal, “zebra-like,” osmiophilic deposits occur in ganglion cells, smooth muscle fibers, and endothelial cells.103

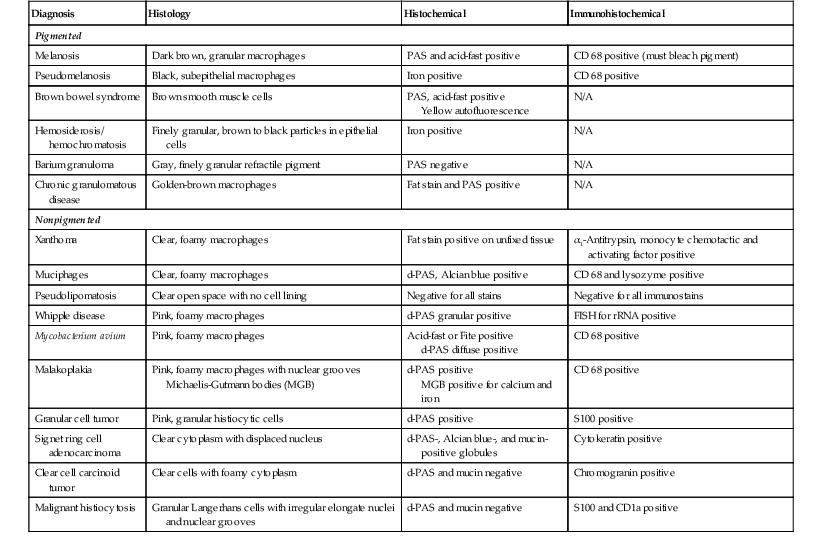

Common Mimics of Lysosomal Storage Diseases

Common mimics of lysosomal storage diseases are summarized in Table 6.3. These are divided into two general categories—pigmented and nonpigmented. The majority of lesions result from a proliferation of histiocytes with either engulfed infectious organisms or cellular or extracellular material. Pigmented lesions, which are in the differential diagnosis of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, include melanosis, pseudomelanosis, brown bowel syndrome, hemosiderosis, and barium granuloma. Nonpigmented lesions are in the differential diagnosis of all of the rest of the lysosomal storage diseases and include xanthoma, muciphages, Whipple disease, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC) infection, pseudolipomatosis, malakoplakia, granular cell tumors, signet ring adenocarcinoma, and malignant histiocytosis.

Table 6.3

Macrophage Infiltrates in the Lamina Propria

| Diagnosis | Histology | Histochemical | Immunohistochemical |

| Pigmented | |||

| Melanosis | Dark brown, granular macrophages | PAS and acid-fast positive | CD 68 positive (must bleach pigment) |

| Pseudomelanosis | Black, subepithelial macrophages | Iron positive | CD 68 positive |

| Brown bowel syndrome | Brown smooth muscle cells | PAS, acid-fast positive Yellow autofluorescence |

N/A |

| Hemosiderosis/ hemochromatosis | Finely granular, brown to black particles in epithelial cells | Iron positive | N/A |

| Barium granuloma | Gray, finely granular refractile pigment | PAS negative | N/A |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | Golden-brown macrophages | Fat stain and PAS positive | N/A |

| Nonpigmented | |||

| Xanthoma | Clear, foamy macrophages | Fat stain positive on unfixed tissue | α1-Antitrypsin, monocyte chemotactic and activating factor positive |

| Muciphages | Clear, foamy macrophages | d-PAS, Alcian blue positive | CD 68 and lysozyme positive |

| Pseudolipomatosis | Clear open space with no cell lining | Negative for all stains | Negative for all immunostains |

| Whipple disease | Pink, foamy macrophages | d-PAS granular positive | FISH for rRNA positive |

| Mycobacterium avium | Pink, foamy macrophages | Acid-fast or Fite positive d-PAS diffuse positive |

CD 68 positive |

| Malakoplakia | Pink, foamy macrophages with nuclear grooves Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (MGB) |

d-PAS positive MGB positive for calcium and iron |

CD 68 positive |

| Granular cell tumor | Pink, granular histiocytic cells | d-PAS positive | S100 positive |

| Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma | Clear cytoplasm with displaced nucleus | d-PAS-, Alcian blue-, and mucin-positive globules | Cytokeratin positive |

| Clear cell carcinoid tumor | Clear cells with foamy cytoplasm | d-PAS and mucin negative | Chromogranin positive |

| Malignant histiocytosis | Granular Langerhans cells with irregular elongate nuclei and nuclear grooves | d-PAS and mucin negative | S100 and CD1a positive |

d-PAS, Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase; FISH, Fluorescence in situ hybridization; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; rRNA, ribosomal ribonucleic acid.

Pigmented Lesions

Melanosis.

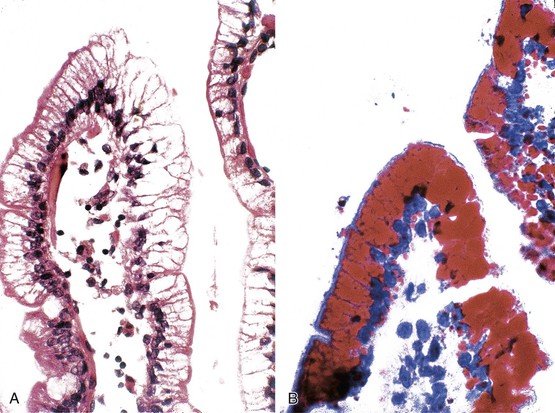

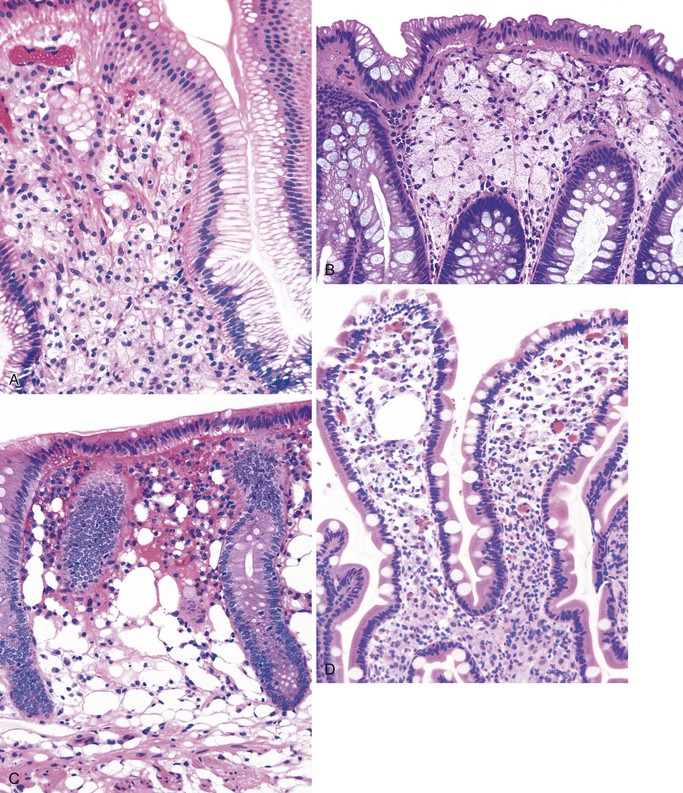

Melanosis coli is characterized by pigment deposition in macrophages in the lamina propria. Endoscopically, the bowel mucosa can appear normal or brownish in color, depending on the amount of pigment present. Occasionally, the pigment is so prominent that the mucosa shows multiple foci of tiny white polypoid lesions on a brown background. The white lesions represent normal or hyperplastic lymphoid aggregates that do not contain pigment.107 Histologically, the pigment in macrophages has a dark brown, granular appearance, and these cells may be located anywhere in the lamina propria (Fig. 6.5, A). It contains polymerized glycolipids, glycoproteins, and melanin (“melanized ceroid”)108 and is typically associated with anthraquinone laxative use. However, a number of studies have shown an association with increased apoptosis of epithelial cells108,109 (caused by laxatives as well as chronic colitis,110 chronic granulomatous disease,111 and bamboo leaf extract112) and have suggested that melanosis is a nonspecific marker of increased apoptosis.

Pseudomelanosis.

This is a rare benign condition characterized by the presence of discrete, flat, small, brown-black spots located typically in duodenal mucosa (speckled duodenum) but also reported in gastric mucosa.113 It occurs in any age group and appears to be associated with upper GI bleeding, chronic renal failure, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus.114 Unlike melanosis coli, it is not associated with use of anthraquinone laxatives. Microscopically, the black pigment is located subepithelially in mucosal macrophages, often at the tips of the villi (see Fig. 6.5, B). Histochemical studies have revealed that the pigment represents a mixture of iron sulfide, hemosiderin, lipomelanin, and ceroid. It is typically negative or only focally positive with iron stains. Electron microscopic studies have revealed the material to be located in lysosomes.

Brown Bowel Syndrome.

This is a rare acquired disorder that is associated with malabsorptive states and vitamin E deficiency. It is characterized by accumulation and deposition of lipofuscin pigment predominantly in the smooth muscle of the bowel, which gives a brown color to the bowel. It occurs most often in the small bowel but can involve the colon or stomach as well. Vitamin E (α-tocopherol) is an antioxidant that prevents peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. It is postulated that a deficiency in this vitamin may result in oxidized lipids, which polymerize with polysaccharides to form the brown pigment. Histologically, the pigment is most prominent in the smooth muscle cells of the muscularis mucosae and propria. Some pigmentation of macrophages, nerves, ganglia, and vascular smooth muscle also is usually observed.115 The distribution of the pigment in conjunction with an appropriate clinical history often helps in differentiation of this lesion from those described earlier. The pigment, which stains positive with PAS, acid-fast, and fat stains on unfixed tissues, also shows the typical bright yellow autofluorescence pattern of lipofuscin. Electron microscopic examination usually reveals mitochondrial damage as well as pigment concentrated in the perinuclear Golgi region.116 Clinically, the pigment does not have any direct effect on the bowel, although defects in contractility,117 intussusception,118 and toxic megacolon have been reported.119

Hemosiderosis/Hemochromatosis.

In advanced iron overload disorders such as hemosiderosis or hemochromatosis, iron is deposited in parenchymal cells throughout the body. In the GI tract, deposits are found most commonly in the parietal cells of the stomach, the Brunner glands in the duodenum, and the epithelial cells of the gut.120,121 Some minor amounts of pigment can also be seen in macrophages. The pigment appears as finely granular, dark brown to black particles. It stains positive with iron stains. The pigment needs to be differentiated from pseudomelanosis duodeni, which is typically larger and located predominantly in macrophages.

Barium Granuloma.

This is a complication of barium examination, typically of the colon. It occurs secondary to extravasation of barium into the wall of the bowel as a result of mucosal injury, overinflation of the rectal balloon, or intrinsic inflammatory disease.122 Endoscopically, it may manifest as a polypoid lesion and may mimic an adenoma or carcinoma. Histologically, one sees a granulomatous reaction surrounding gray, finely granular, refractile, PAS-negative material located in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and in the lamina propria (see Fig. 6.5, C). The material is not birefringent. Radiographs of the paraffin block can help reveal the presence of radiopaque material.123

Nonpigmented Lesions

Xanthoma.

This is a fairly common lesion of the GI tract most commonly found in the stomach. The terms xanthoma, xanthelasma, lipid island, and xanthogranulomatous inflammation are used synonymously. Endoscopically, xanthomas appear as small yellow nodules or streaks on the mucosa. They represent an accumulation of lipid and cholesterol within macrophages. Microscopically, one sees a collection of macrophages containing foamy cytoplasm positive for fat stains on unfixed tissue (Fig. 6.6, A). Immunohistochemical stains for α1-antitrypsin and monocyte chemotactic and activating factor are also typically positive,124 whereas cytokeratin and mucin stains are negative. The lesions are typically associated with chronic inflammatory states125 but can be seen with malignancies.124

Muciphages.

These are mucin-rich phagocytes that accumulate as a result of mucosal damage. They are most common in the rectum (as many as 40% of all rectal biopsies contain muciphages)126 and are also commonly found in the lamina propria and in the stalk of adenomatous polyps.127 Endoscopically, muciphages can appear as polyps or nodules. Histologically, foamy histiocytes containing coarse cytoplasmic vacuoles are present in the superficial lamina propria (see Fig. 6.6, B). Mild fibrosis and architectural distortion may occur in cases associated with a previous injury.128 Histochemical stains with d-PAS (PAS with diastase digestion) and Alcian blue at pH 2.5 and with immunohistochemical stains for CD68 and lysozyme are positive in muciphages.

Pseudolipomatosis.

This is a common iatrogenic lesion caused by influx of air into the mucosa secondary to endoscopy-related trauma. It is a benign, transient lesion129 that is characterized histologically by clear open spaces in the lamina propria or submucosa, representing trapped gas, without an epithelial or endothelial cell lining130 (see Fig. 6.6, C). These clear spaces do not stain with any specific immunohistochemical or histochemical reaction.

Whipple Disease.

This is a systemic infection that is caused by a cultivation-resistant bacterium, Tropheryma whippelii. In the GI tract, it is primarily found in the small bowel; however, it can involve the stomach,131 esophagus, and colon as well.132 Histologically, one sees characteristic abundant, pink-colored, foamy macrophages filling the lamina propria. These macrophages may contain small granules that are positive for d-PAS. Extracellular lipid is often present as well (see Fig. 6.6, D). Electron microscopic examination reveals intracellular and extracellular bacterial rods in various stages of disintegration. These bacteria are also found within IgA-positive plasma cells.133 With the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for ribosomal RNA, the active organism appears to be most prevalent near the tips of intestinal villi in the lamina propria.134

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Complex Infection.

This is a common pathogen in AIDS that may also be seen in other immunocompromised patients.135 It typically affects the small bowel and colon. Endoscopically, the mucosa can appear normal or coarsely granular.136 Histologically, abundant, variably sized sheets of foamy macrophages are seen in the lamina propria and cause widening of the villi (see Fig. 6.6, E). Diagnosis is made with acid-fast or Fite stain positivity; numerous elongated organisms are revealed within the macrophages. PAS stain typically reveals a relatively diffuse fibrillary staining pattern in macrophages, as opposed to the granular staining characteristic of Whipple disease. The organisms are typically intact, unlike the various stages of disintegration that are seen in Whipple disease.

Malakoplakia.

This is a rare bacterial infection that affects patients with an underlying macrophage phagolysosome defect (not typically seen in patients with AIDS).137 It is usually caused by Escherichia coli or Klebsiella spp.138 and is often seen in the urinary tract. However, it can involve any portion of the GI tract. Endoscopically, the mucosa shows numerous soft yellow plaques on the mucosa. Rarely, a mass lesion composed of macrophages may develop as well. Histologically, there is infiltration of the lamina propria by neutrophils and abundant macrophages; the latter often contain nuclear grooves (see Fig. 6.6, F). Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, which are small, pale, intracytoplasmic concretions that stain for calcium and iron, are diagnostic. Macrophages also stain with d-PAS. Electron microscopic examination reveals degenerated bacilli in phagolysosomes, similar to those seen in Whipple disease.139

Granular Cell Tumor.

These tumors are believed to be of neurogenic origin and are typically found in the esophagus, but they can occur anywhere in the GI tract.140 Rare cases have been described in the small bowel and colon.141,142 They are mostly benign, but malignant tumors have rarely been described. The tumors typically manifest as nodules in patients with nonspecific GI symptoms. Histologically, these tumors include abundant epithelioid or histiocytic cells with distinct pink granular cytoplasm in the lamina propria or submucosa (see Fig. 6.6, G). The cells are positive for d-PAS and are strongly S100 positive. Electron microscopic examination reveals cells filled with giant autophagic vacuoles (lysosomes) that contain myelin-like debris of giant lysosomes.

Signet Ring Cell Adenocarcinoma.

This tumor (described in detail in Chapters 25 and 27) shows an infiltration of malignant cells with clear cytoplasm and an eccentrically placed hyperchromatic nucleus (see Fig. 6.6, H). It is differentiated from other lesions by the presence of highly atypical nuclear features and by positivity with mucin and cytokeratin stains.143

Clear Cell Carcinoid Tumor.

A rare case has been reported of a gastric carcinoid composed entirely of clear cells with foamy cytoplasm.144 Immunopositivity for endocrine markers such as chromogranin A or electron microscopic demonstration of dense core granules helps define the lesion.

Malignant Histiocytosis.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis can involve any portion of the GI tract, either as part of generalized disease or as a separate primary entity. Involved areas may manifest as a polypoid or mass lesion. Histologically, one sees a mucosal infiltrate composed of Langerhans cells that have irregular, elongated nuclei and prominent nuclear grooves and folds. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells is abundant and finely granular. These tumors are usually associated with a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate as well. As with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, invasion and destruction of the epithelium are common.145 Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and CD1a are intensely positive in tumor cells. Electron microscopic examination reveals Birbeck granules in the cytoplasm of tumor cells.146

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is not a single disease but the product of a variety of diseases. The common feature of these diseases is extracellular deposition of amyloid proteins that stain with Congo red and show apple-green birefringence under polarized light. The proteins have a typical fibrillary appearance on electron microscopy. All amyloid fibrils are protein complexes with a common tertiary molecular structure, referred to as a twisted β-pleated sheet pattern.

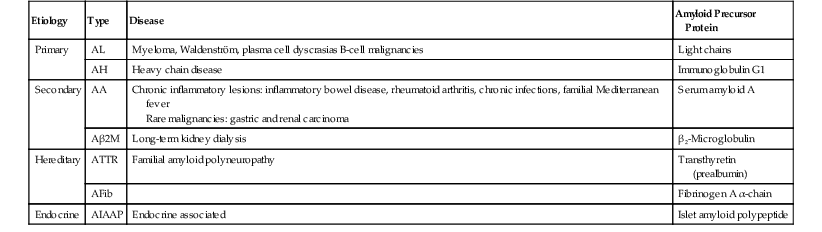

Classification

Historically, amyloidosis was classified according to its clinical presentation (localized versus diffuse) or its underlying cause (primary, secondary, hereditary, or endocrine related); now, the classification is determined on the basis of the biochemical composition of the amyloid fibrils (Table 6.4). The most common types that involve the GI tract are AA, AL, and Aβ 2M. In addition to the more common proteins listed in the table, a number of other types of amyloid proteins have been described, such as Aβ (β protein precursor), AApoA1 (apolipoprotein A1), ALys (lysozyme), ACys (cystatin C), and AGel (gelsolin).

Table 6.4

Amyloidosis

| Etiology | Type | Disease | Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| Primary | AL | Myeloma, Waldenström, plasma cell dyscrasias B-cell malignancies | Light chains |

| AH | Heavy chain disease | Immunoglobulin G1 | |

| Secondary | AA | Chronic inflammatory lesions: inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic infections, familial Mediterranean fever Rare malignancies: gastric and renal carcinoma |

Serum amyloid A |

| Aβ2M | Long-term kidney dialysis | β2-Microglobulin | |

| Hereditary | ATTR | Familial amyloid polyneuropathy | Transthyretin (prealbumin) |

| AFib | Fibrinogen A α-chain | ||

| Endocrine | AIAAP | Endocrine associated | Islet amyloid polypeptide |

Clinical Features

GI involvement is common in all types of systemic amyloidosis (primary and secondary), ranging from 85% to 100%.147–149 In most cases associated with systemic amyloidosis, patchy involvement of the GI tract is seen without associated symptoms. However, a variety of GI symptoms may occur, including bleeding,150 pseudo-obstruction,151 decreased motility,152 and, rarely, perforation.153 The greater the number of deposits and the more widespread the involvement, the higher the likelihood of clinical symptoms. Vascular involvement by amyloid produces fragility and rupture of affected vessels, which can lead to the development of petechial hemorrhage of the mucosa and ischemic disease and its manifestations. In fact, ulcerating lesions may mimic IBD grossly.154

Amyloid infiltration within nerve155 and muscle fibers156 can cause motility disorders. Malabsorption may result from stasis and bacterial overgrowth. Finally, amyloidosis can occasionally manifest as a solitary mass lesion or polyp that mimics a malignant tumor.157 Endoscopically, the mucosa may appear normal or may show a fine granular appearance with erosions, friability, and thickening of the valvulae conniventes.158,159

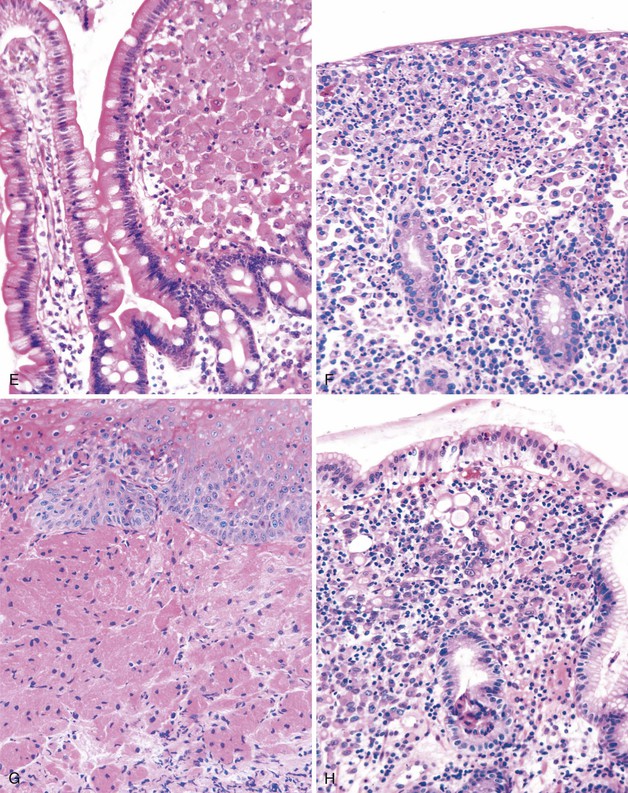

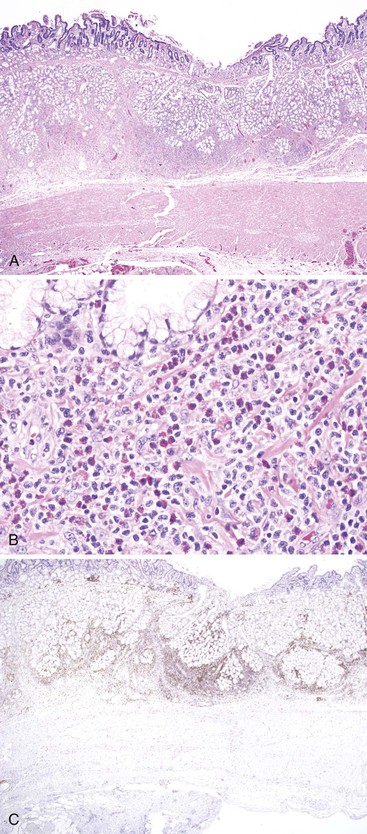

Pathologic Features

Microscopically, amyloid deposits are extracellular and have a classic waxy, homogeneous appearance (Fig. 6.7, A). Pink hyaline amyloid may contain small, slitlike spaces caused by cracking during tissue processing. Histochemical stains for Congo red (the most specific), toluidine blue, crystal violet, fluorochrome, and thioflavine are usually positive with all types of amyloid (see Fig. 6.7, B). Amyloid also stains positive with the PAS reaction and negative with lipid and mineral stains. In general, AA amyloid seems to localize to capillaries, small arterioles, and the mucosa. AL amyloid is often found in the muscularis propria and in medium-sized to large vessels. Aβ2M amyloid is found mainly in the muscularis propria and in small arterioles and venules, forming subendothelial nodular lesions.160 AL and AA forms also can be distinguished by pretreatment with potassium permanganate. This pretreatment abolishes the Congo red affinity of the AA fibrils but not that of the AL fibrils.161 Immunohistochemical stains with antibodies to amyloid A, immunoglobulins λ and κ light chain amyloid fibril proteins, β2-microglobulin, and transthyretin characterize the majority of amyloid deposits.162 Electron microscopy reveals an interlocking meshwork of fibrils that measure 7.5 to 10 nm in diameter with variable length.

Amyloidosis should be differentiated from arteriosclerosis in blood vessels and from collagen in the lamina propria, submucosa, and muscularis (in systemic sclerosis). Congo red stains can help with this differential diagnosis in that neither arteriosclerosis nor collagen stains with Congo red. One study suggested that Congo red stain may not be sensitive enough in patients with early amyloidosis in minute amounts.163

GI biopsy is a procedure commonly used to diagnosis amyloidosis. Rectal biopsies have a sensitivity of 85%, compared with a sensitivity of 54% for fat biopsies.147 In the rectum, amyloid deposits are most commonly seen in small arterioles and veins in the submucosa; therefore, a deep suction biopsy is usually required for adequate evaluation. Some studies have suggested that gastric or small bowel biopsies have a sensitivity as high as 100% for the diagnosis of amyloidosis.156,164

Familial Mediterranean Fever (Familial Paroxysmal Polyserositis, Recurring Polyserositis)

Familial Mediterranean fever is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder seen almost exclusively in Sephardic Jews, Arabs, Armenians, and people of Turkish descent. It is characterized by recurring and self-limited attacks of fevers and serosal inflammation involving the peritoneal, synovial, and pleural membranes. This disease typically begins in childhood or adolescence and recurs at irregular intervals throughout life.165 GI involvement consists of acute inflammation limited to the serosal surfaces of the bowel (peritonitis). Repeated episodes can result in the formation of peritoneal adhesions that may cause obstruction. Systemic amyloidosis may also occur in untreated patients. The AA amyloid type is believed to develop as a consequence of recurrent inflammation. Furthermore, amyloid deposits in the lamina propria and the submucosal vessels may occur without symptoms. The disease is often treated with colchicine.

Pulmonary Disorders

Hypoxia-producing pulmonary disorders can lead to ischemic injury of the GI tract. An increased incidence of peptic ulcer disease has also been described in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.166 This is thought to be the result of hypercapnia, which stimulates gastric acid secretion. Pneumonia, bronchitis, asthma, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are all associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).167 It is also believed that GERD may cause or exacerbate several pulmonary diseases.

Reproductive Disorders

Effects of Pregnancy and Exogenous Hormones

A number of GI problems may develop during pregnancy. Nausea, vomiting, and heartburn are common in the first trimester. Some studies suggest that these effects are secondary to human chorionic gonadotropin or estrogen secretion,168 which leads to abnormalities in gastric myoelectrical activity and contractility.169 Secondary esophagitis may develop as a result of severe vomiting. Reflux, peptic ulcers, Helicobacter pylori infection, and cholecystitis are also increased. In addition, constipation is a frequent problem during the late stages of pregnancy. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and rectal wall prolapse can occur secondary to vaginal delivery.170

Pregnancy outcomes are generally good in patients with IBD. Population studies suggest that maternal IBD is associated with increased odds of preterm delivery, low birth weight, smallness for gestational age (Crohn’s disease), and congenital malformations (ulcerative colitis).171–173 The risk of pregnancy-related complications and the disease behavior during pregnancy depend mainly on disease activity at the time of conception. However, pregnancy does not seem to influence the course of IBD. Most drugs used to treat IBD are safe to use in pregnancy and breast feeding. Biologic agents do cross the placenta (mainly in the third trimester) and are often held after 30 weeks’ gestation and restarted after delivery.174

Oral contraceptive pills and exogenous estrogens are associated with nausea and vomiting. They also are associated with thrombosis and, consequently, an increased risk for ischemia of the small bowel and colon.175

Decidualization of the Peritoneum

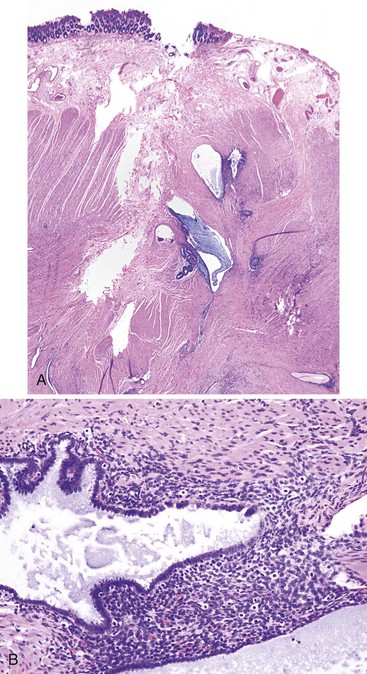

Ectopic decidualization of the peritoneum is a rare lesion. It can yield macroscopic nodules (peritoneal deciduosis or deciduosis peritonei) that mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis.176 Grossly, multiple light-tan peritoneal masses or nodules typically are identified at the time of caesarean section. Microscopically, plump pink (decidualized) cells are present between the mesothelial cells and muscularis propria (Fig. 6.8). This is a physiologic reaction with an excellent prognosis and spontaneous resolution after delivery.

Endometriosis

Clinical Features

Endometriosis is a condition characterized by the presence of endometrial glands or stroma outside of the uterus. It can involve any portion of the GI tract. The most common sites of involvement are organs in the pelvis such as the rectosigmoid colon, appendix, and small bowel. The GI tract is involved in 12% to 37% of cases.177 Intestinal endometriosis is usually asymptomatic. However, when symptomatic, it typically causes obstructive symptoms as a result of adhesions. Complete obstruction of the bowel lumen occurs in fewer than 1% of cases.177 Other atypical presentations include diarrhea and GI bleeding. Symptoms are often temporally associated with the onset of menses.

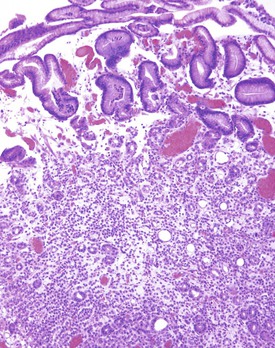

Pathologic Features

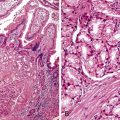

Endometriosis may be solitary or multifocal, and it may manifest as a mass lesion or with volvulus, intussusception, luminal narrowing, or adhesions. Endometrial glands or stroma are usually present on the serosal surface but may involve any layer of the bowel wall. On a cut surface, the endometriosis often appears sclerotic with punctate hemorrhagic or brown areas. Microscopically, this disorder is characterized by the presence of endometrial-type glands or stroma (smaller, slightly elongated cells that are packed together, often with intermingled red blood cells) and hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 6.9). At least two of these three findings should be present for a diagnosis of endometriosis to be established with certainty. In addition, fibrosis and prominent smooth muscle proliferation may surround foci of endometriosis. Fresh hemorrhage may occur. Immunohistochemical staining for estrogen receptors is usually positive in both the glands and stromal cells.178

Differential Diagnosis

Most importantly, the differential diagnosis includes invasive adenocarcinoma. This can be extremely problematic to differentiate on fine-needle aspiration specimens. With this sampling procedure, the glandular epithelium is preferentially aspirated and may show nuclear atypia, mimicking an adenocarcinoma. The finding of hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and stromal cells helps establish a correct diagnosis. On histologic section, differentiation from adenocarcinoma depends on the finding of characteristic stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, in addition to glandular epithelium. Endometriosis may occasionally be present in mucosal biopsies,179 and can resemble colitis cystica profunda. If smooth muscle proliferation is prominent, differentiation from a leiomyoma can be achieved by deeper sectioning of the tissue to look for glandular epithelium. In difficult cases, colonic glands are positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, whereas endometrial glands are negative for this peptide.180

Rheumatologic Disorders

Connective tissue disorders can affect the GI tract in a variety of ways. They can cause hypomotility, secondary to muscle inflammation or atrophy, or ischemic disease, secondary to vasculitis. A variety of lesions may develop secondary to pharmacologic therapy for these disorders. Hypomotility is most commonly seen in scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease, and polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Vasculitis predominates in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, and Behçet syndrome. The majority of these disorders are treated with antiinflammatory drugs that can have major GI effects. For example, rheumatoid arthritis is typically treated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can cause peptic ulceration and bleeding.

Scleroderma

Scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis) is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, upregulated collagen production, and vasculitis. GI involvement is common and is typically characterized by hypomotility (see Chapter 7 for details). Scleroderma can be part of the CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal involvement, sclerodactyly, and telangiectases). Scleroderma most commonly involves the esophagus; manometric abnormalities are seen in up to 90% of patients.181 However, abnormalities of the entire GI tract may also be observed. Colonic dysfunction has been reported in up to 20% of patients.182

In the esophagus, lower esophageal sphincter pressure is reduced and gastric emptying of the stomach is delayed.183 Both of these factors increase the incidence of GERD, erosive esophagitis, and stricture formation. The small and large intestine may also be involved. Typical features include scattered wide-mouthed diverticula,184 pseudo-obstruction,185 and intestinal perforation.186

Pathologically, scleroderma is characterized by smooth muscle atrophy and its replacement by collagenized fibrous tissue (Fig. 6.10). The lesion most commonly affects the inner circular muscle layer but can involve the entire muscularis propria on occasion. Fibrous tissue is highlighted by the trichrome stain, which reveals atrophy and loss of muscle tissue. Fibrosis may also involve the submucosa to a variable degree.187 Muscular atrophy results in atony and dilation and produces wide-mouthed pseudodiverticula that can be identified radiographically. In addition, the small vessels of the bowel may show a proliferative endarteritis and mucinous changes of the media.188 Rarely, ischemic ulcers can occur as a result.

Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are inflammatory myopathies that primarily involve skeletal muscle. Skin involvement occurs also in dermatomyositis. These disorders may be associated with motor dysfunction of the GI tract.189 The striated muscle of the cervical esophagus is most frequently affected when delayed esophageal emptying is common.190 Histologic changes include chronic inflammation, edema, and muscle atrophy. Features can mimic scleroderma, but fibrosis is not prominent in these disorders.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE is a systemic multisystem autoimmune disease that affects the GI tract in approximately 20% of patients. The development of vasculitis can lead to ischemia191 and perforation of the GI tract. SLE also has been associated with malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy,192 and amyloidosis.193

Rheumatoid Arthritis

GI involvement occurs in 25% of patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis.196 Notably, this occurs in the form of a necrotizing vasculitis that affects small to medium-sized arteries, similar to polyarteritis nodosa. The condition is usually asymptomatic. However, hemorrhage or even perforation may occur.197 GI lesions may also be seen in association with long-term use of NSAIDs, and in rare cases, long-standing inflammation can lead to amyloidosis.

Reactive Arthritis

The term reactive arthritis refers to a group of inflammatory disorders associated with arthritis (spondyloarthropathy). It includes psoriatic arthritis, Reiter syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and arthritis associated with IBD. Most affected individuals (70%)198 have chronic active colitis. Interestingly, clinical remission is always associated with normal gut histology.199

Sjögren Syndrome

Sjögren syndrome is a clinicopathologic entity characterized by dry eyes and mouth secondary to immune-mediated destruction of the lacrimal and salivary glands. Patients with Sjögren syndrome may develop immune-mediated destruction of the pharyngeal and esophageal glands with fissuring and ulceration of the pharynx and esophagus. Esophageal webs have been observed in up to 10% of patients. Atrophic gastritis, atrophy, and chronic inflammation of the esophageal glands have been noted as well.200 Histologically, the salivary glands of the esophagus show a periductal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate that can occasionally be quite marked.

Hereditary Connective Tissue Disorders

Hereditary connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and pseudoxanthoma elasticum, result from a defect in collagen synthesis or structure. These defects result in thinning of the bowel wall and vascular structures201; patients are at increased risk for GI hemorrhage and perforation.202 Patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome also have diaphragmatic hernias and GI diverticula. Upper GI tract hemorrhage occurs in 13% of patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum.203 In these cases, submucosal, yellowish, nodular lesions, similar to xanthoma-like skin lesions, may be seen.204 Histologic examination typically reveals superficial mucosal hemorrhage, erosion, and elastic tissue degeneration of small and medium-sized arteries with calcified plaque formation.

Urologic Disorders

Acute Renal Failure

Postsurgical or trauma-associated acute renal failure often results in gastric or duodenal erosions, ulceration, and hemorrhage secondary to hypotension, stress, and multiorgan failure.205

Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome

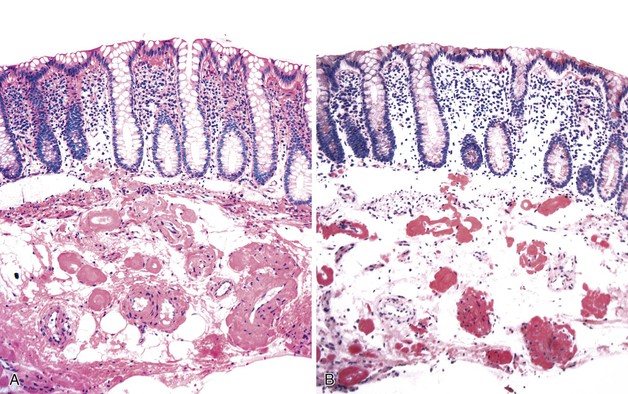

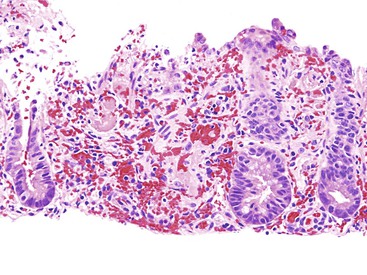

HUS is an acute onset of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal dysfunction. Cases associated with E. coli infection often manifest with a GI prodrome that is difficult to differentiate histologically from an acute colitis.206 Presentations mimicking intestinal intussusception207 and ulcerative colitis have also been described.208 During HUS, an associated colitis is seen in most patients, and there is a 1% to 2% incidence of colonic perforation.209 Marked mucosal and submucosal edema and hemorrhage of the colon can occur, but inflammation usually is not significant (Fig. 6.11). Microvascular angiopathy with endothelial cell damage and overt thrombosis may also be observed.210

Chronic Renal Failure

A variety of GI lesions may develop in patients with chronic renal failure. These are mainly associated with uremia, long-term hemodialysis, or kidney transplantation.

Uremia

GI symptoms that are common among patients with uremia include GERD,211 nausea, vomiting, anorexia, epigastric pain, and upper GI hemorrhage. Early studies suggested an increased incidence of dyspepsia, ulcer disease, and H. pylori gastritis. However, studies indicate that the incidence of these conditions is not significantly different from that in the general population.212 GI hemorrhage occurs in up to 15% of patients, accounts for 15% to 20% of all deaths in patients on long-term dialysis, and is often associated with angiodysplasia. Bleeding abnormalities may also occur as a result of platelet dysfunction. Mucosal abnormalities range from edema to ulceration and occur in 60% of patients who die from uremia.213 The pathogenesis of uremic syndrome–associated GI tract disease is unclear. However, many manifestations of uremia are relieved by dialysis, which suggests a role for humoral factors. In addition, gastric mucosal calcinosis may be identified in patients with chronic renal failure or uremia and after renal transplantation.214 Microscopically, calcinosis appears as small, white, flat plaques or nodules that contain amorphous basophilic deposits within the subepithelial compartment of the superficial lamina propria.

Long-Term Hemodialysis

Acute fluid loss during the process of dialysis can lead to hypotension and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia.215,216 Peritonitis secondary to bacterial infection and acute bowel obstruction secondary to incarcerated hernia into the catheter tract can also develop in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis.217 Patients on dialysis are also susceptible to Salmonella spp. enteritis218 and dialysis-associated β2-microglobulin amyloidosis.219

Kidney Transplantation

GI complications are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in kidney transplant recipients.220 Complications are mainly related to immunosuppression therapy. Patients are at risk for opportunistic infections, including Candida spp., cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus, Cryptosporidium spp., and Strongyloides spp.. These patients also are at increased risk for exacerbation of diverticulitis, for unknown reasons.221

Urinary Conduits

Three basic types of urinary diversion have been used in the treatment of congenital or malignant disorders—ureterosigmoidostomy, ileal neobladder, and antirefluxing colonic conduits.

Ureterosigmoidostomy, whereby the ureter is implanted into the sigmoid colon, is associated with a greatly increased risk for colonic neoplasia at or near the site of anastomosis.222 Hence, this type of diversion is no longer popular. Adenocarcinomas typically arise 15 to 25 years after surgery and are histologically identical to typical colon adenocarcinomas. Endoscopic surveillance biopsies are recommended to screen for epithelial dysplasia.223 In addition to dysplasia, one may see inflammatory polyps, edema, crypt branching, and Paneth cell metaplasia.222,224

Creation of an ileal neobladder (Kock or Charleston pouch) is now the most common procedure performed in patients who require some form of urinary diversion. These pouches are created from a portion of ileum that is separated from the fecal stream, and risk of malignancy has not been associated with these procedures. However, mucosal biopsy of these pouches may reveal histologic changes over time. Early changes (over the first year) include shortening of villi with loss of microvilli and decreased numbers of goblet cells.225 Late changes (after 4 years) consist of marked flattening of the epithelium with epithelial stratification, similar to urothelium.226 Dysplasia has not been described.

Antirefluxing colonic conduits, using a segment of colon that is isolated from the fecal stream, appear to be associated with a lower degree of retrograde reflux and therefore a decreased incidence of pyelonephritis.

Miscellaneous Disorders

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

Chronic granulomatous disease (discussed further in Chapter 9) is a rare X-linked or autosomal recessive inherited disorder of phagocyte function. It is characterized by recurrent infections in infants and children.227 Affected children suffer from chronic infections, often with abscess formation, in many organs. The GI system is involved in approximately 25% of patients.228 Patients may present with vitamin B12 deficiency and an abnormal Schilling test result that is not corrected by the addition of intrinsic factor, as well as steatorrhea, obstruction, or bleeding. The defect lies in the inability of the body to destroy catalase-positive bacteria and fungi due to a lack of hydrogen peroxide production by phagocytic leukocytes. This condition may be diagnosed by the finding of a negative nitroblue tetrazolium assay or by other tests that reveal decreased bactericidal activity of leukocytes.

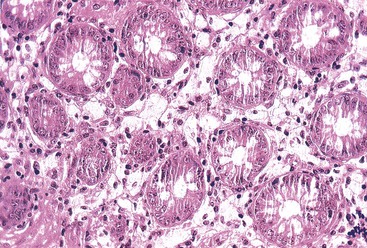

The condition is characterized by necrosis and abscess and sinus tract formation, which may be seen in the form of gastric outlet obstruction,228,229 perineal abscess, diffuse colitis,230 or even esophageal narrowing.231 Histologically, necrotizing lesions often have sparse and poorly formed granulomas, frequently with marked eosinophilia. Microorganisms usually are not detectable in the lesion. The mucosa of the small and large intestine shows clusters of enlarged macrophages, often located adjacent to the muscularis mucosae in the basal portion of the lamina propria. The macrophages range from 50 to 100 µm in diameter and contain a golden-brown lipofuscin type of pigment (Fig. 6.12). The pigment stains positively with fat stains and the PAS reaction. The pigment is refractile on standard histologic section as well. Rectal biopsy may show an increased number of inflammatory cells (including plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils) in the lamina propria.

The differential diagnosis includes other granulomatous disorders, such as mycobacterial and fungal infections, sarcoidosis, and IBD. These lesions can be excluded by stains or cultures and by appropriate clinical history. Pigment-laden macrophages may resemble several storage disorders, such as Batten disease and brown bowel syndrome. Other storage disorders typically do not involve PAS-positive pigments. Whipple disease and MAC infection have PAS-positive material but are not typically refractile. Finally, melanosis coli may have a similar pigment, but macrophages in this condition are usually more prominent in the superficial lamina propria and are not usually present in the small intestine.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis rarely involves the GI tract. The stomach is the most common site of sarcoidosis,232 although involvement of the entire GI tract has been reported. It occurs in middle-aged patients and is usually associated with pulmonary disease, although the GI tract may rarely be the first site of involvement. Sarcoidosis is characterized by an abnormal immune response and the formation of multiple noncaseating granulomas. This condition is also associated with high serum angiotensin-converting enzyme activity. 233 The cause is unknown. In patients with sarcoidosis, a high frequency of humoral autoimmunity (increased incidence of antibodies to H+,K+-ATPase, gliadin, and endomysium) is seen.234 However, there does not appear to be an increased incidence of pernicious anemia or celiac disease.

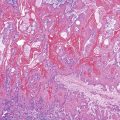

The pathology of sarcoidosis is variable. The mucosa may show no abnormalities, or it may be severely involved, with a linitis plastica–like appearance of the stomach.235 Ulceration and bleeding have been reported. Microscopically, the hallmark of sarcoidosis is the presence of noncaseating granulomas. These granulomas are composed of epithelioid histiocytes, with or without giant cells, and are often associated with a rim of lymphocytes at the periphery (Fig. 6.13). They may be present in any layer of the bowel wall and may be associated with tissue damage.