Systemic disease

Renal disease

Diseases of the kidney are associated with a remarkably wide range of possible haematological abnormalities (Table 48.1).

Table 48.1

Haematological changes in renal disease

| Abnormality | Clinical association | |

| Red cells | Anaemia | Chronic renal failure |

| Polycythaemia | Renal carcinoma, cystic disease, hydronephrosis, parenchymal disease, Bartter’s syndrome, renal transplantation | |

| Burr cells | Renal failure | |

| Haemostasis | Abnormal platelet function | Renal failure |

| Thrombocytopenia | ||

| Disordered coagulation1 |

1The complex coagulation abnormalities of renal failure usually lead to a bleeding tendency but nephrotic syndrome is associated with an increased incidence of thrombosis.

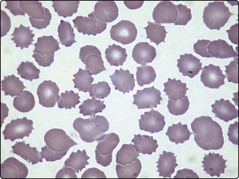

Anaemia is almost inevitable in chronic renal failure. The pathogenesis is complex but impaired erythropoietin production is the principal cause. Other possible contributory factors include the release of inhibitors of erythropoiesis, mild haemolysis and iron deficiency. The anaemia of renal failure is typically normocytic and normochromic. A characteristic finding in the blood film is the presence of burr cells (Fig 48.1). The best treatment of anaemia is resolution of the underlying renal problem (e.g. by transplantation), but where this is not feasible, recombinant erythropoietin is the treatment of choice. Intermittent bolus administration generally leads to a marked improvement in anaemia and transfusion independence. A failure of the anaemia to respond to erythropoietin should prompt a search for other aetiologies such as iron deficiency.

Paradoxically, some forms of renal disease can lead to increased red cell production and clinical polycythaemia (see Table 48.1). This arises either from inappropriate secretion of erythropoietin by a kidney tumour or from local renal hypoxia promoting erythropoietin release from normal cells. Polycythaemia can be the presenting feature of renal carcinoma and rapid identification of the malignancy may allow curative surgical treatment. Benign diseases such as polycystic disease and hydronephrosis probably cause polycythaemia by inducing renal ischaemia. The polycythaemia of renal disease is not an appropriate physiological response and patients with high haematocrits can derive benefit from regular venesection.

Chronic renal failure is also associated with a large number of possible platelet and coagulation abnormalities. The increased risk of bleeding in these patients is generally caused by the complex interaction of abnormalities shown in Table 48.1. Anaemia tends to worsen bleeding by interfering with the normal interaction between platelets and vascular endothelium.

Malignancy

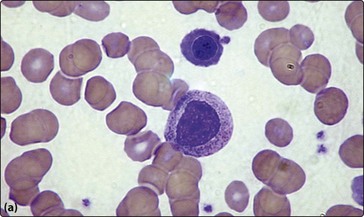

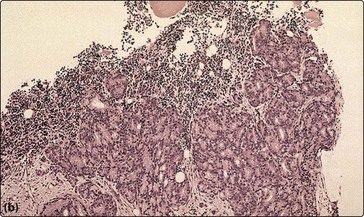

Anaemia is seen in around half of patients with non-haematological malignant tumours. The anaemia of chronic disease is the most common aetiology (p. 36) but other causes include chemotherapy, blood loss, haemolysis and marrow infiltration. Invasion of the bone marrow by solid tumours can result in a pancytopenia and a characteristic leucoerythroblastic blood picture with circulating nucleated red cells and myelocytes (Fig 48.2a). Clumps of malignant cells may be seen in a bone marrow aspirate but a bone marrow trephine is a more reliable way of demonstrating solid malignancy (Fig 48.2b).

Infections

Infectious mononucleosis

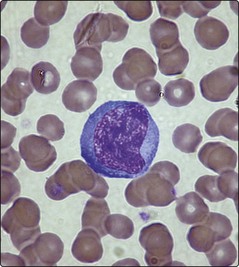

Infectious mononucleosis (or glandular fever) is a disorder caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). It predominantly affects adolescents and young adults. Clinical features often include malaise, fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly and hepatitis. There is a small risk of splenic rupture. The haematological hallmark of the disease is the presence of numerous atypical lymphocytes in the blood (Fig 48.3). These lymphocytes are mainly activated T-cells produced as an immunological response to EBV-infected B-lymphocytes. Other possible blood changes are neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and a cold-type autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. The differential diagnosis is essentially other viral diseases, but where the blood abnormalities are severe the disease may be confused with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. The diagnosis is supported by positive Paul–Bunnel or Monospot tests which rely on the detection of heterophile antibodies that appear in the serum. If these tests are negative and there remains clinical suspicion of the disorder then EBV-specific serodiagnostic tests should be performed. Treatment of infectious mononucleosis is essentially symptomatic, although corticosteroids can be helpful in unusually difficult cases.

HIV infection

Progressive HIV infection has many possible haematological consequences (Table 48.2). These result from a combination of a direct effect of the virus, opportunistic infection and side-effects from the drugs used in treatment. The blood changes are often similar to those seen in other viral infections but a chronic decline in the lymphocyte count is a particular feature. Examination of the bone marrow often reveals non-specific features such as changes in cellularity, fibrosis, trilineage myelodysplasia, increased plasma cells and prominent haemophagocytosis. The presence of granulomas can signify infection by atypical mycobacteria or other opportunistic pathogens. In clinical practice the major haematological problems associated with HIV infection are immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and lymphomas. The latter are typically aggressive B-cell malignancies with extranodal involvement.

Table 48.2

Possible haematological changes in HIV infection

| Blood | Lymphopenia |

| Anaemia | |

| Neutropenia | |

| Thrombocytopenia | |

| Atypical lymphocyte morphology | |

| Anisopoikilocytosis | |

| Macrocytosis1 | |

| Bone marrow | Variable changes in cellularity |

| Dysplasia | |

| Increased plasma cells | |

| Increased fibrosis | |

| Haemophagocytosis | |

| Opportunistic infection (e.g. granulomas) | |

| Lymphoid aggregates | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Other | Positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) |

| Lupus anticoagulant |