Chapter 28 Syphilis

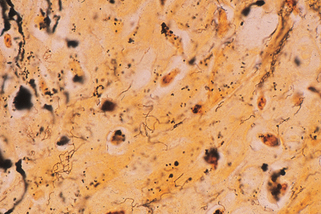

Figure 28-1. Biopsy of secondary syphilis demonstrating numerous spirochetes in the epidermis (Warthin-Starry stain, ×1000).

Tognotti E: The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Europe, J Med Humanit 30:99–113, 2009.

Figure 28-3. A typical presentation of primary syphilis demonstrating two chancres.

(Courtesy of William James, MD.)

Lee V, Kinghorn G: Syphilis: an update, Clin Med 8:330–333, 2008.

In lieu of these procedures, a presumptive diagnosis can be made by serologic tests (see Chapter 3). The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test are negative in early primary syphilis and should be repeated weekly for 1 month to be considered as negative. The diagnosis is more likely if a rising titer can be demonstrated. The fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) test turns positive earlier and is more sensitive.

Baughn RE, Musher DM: Secondary syphilitic lesions, Clin Microbiol Rev 18:205–216, 2005.

Key Points: Syphilis

The skin lesions of late benign syphilis present as nodules and plaques that demonstrate a tendency for central healing and peripheral extension. The central healed areas characteristically demonstrate scarring and atrophy (Fig. 28-7). The mucosal lesions may involve any mucosal surface but demonstrate a tendency to extend to and destroy the nasal cartilage, producing a “saddle nose” deformity. Involvement of the mucosa over the hard palate may produce a perforation.