48 Syncope

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Syncope occurs when cerebral blood flow decreases below 30% to 50% of baseline. This decrease may be the result of systemic vasodilation, decreased cardiac output, or both. This results in transient ischemia, causing temporary loss of consciousness and motor tone. Syncope may also be accompanied by brief autonomic movements. Syncope should be distinguished from presyncope (dizziness or lightheadedness without loss of consciousness), vertigo (the sensation of spinning), and syncopal-like events (e.g., seizures, migraines, or conversion disorder). The causes of syncope can be divided into three major categories: neurally mediated, cardiac, and metabolic (Box 48-1). Syncopal-like events are discussed briefly in the following section.

Box 48-1 Differential Diagnosis of Presentation for “Syncope”

Neurally Mediated Syncope

Cardiac Syncope

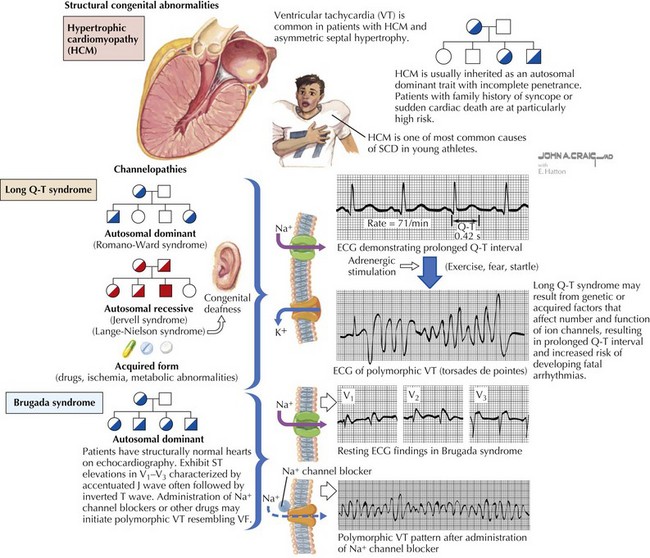

Although a cardiac cause is found in fewer than 2% of previously healthy children with syncope, it is important to recognize because it can be associated with an increased risk of sudden death. Cardiac syncope results from abrupt decline in cardiac output as the result of obstructive lesions (aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [HCM]), myocardial dysfunction (ischemia, cardiomyopathy), or primary arrhythmias (Figure 48-1). Many of these conditions can be asymptomatic until syncope or sudden death occurs. Arrhythmias can also occur secondary to structural heart disease, to myocardial dysfunction, or to postoperative changes in association with congenital heart disease. Any concern for a cardiac syncope warrants a referral to a pediatric cardiologist. Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young is estimated to affect between one in 50,000 and one in 200,000 children.

Arrhythmias

Some of the arrhythmias associated with cardiac syncope are reviewed here. For further discussion of arrhythmias, please refer to Chapter 45.

Preexcitation Syndromes

Preexcitation syndromes are characterized by premature ventricular stimulation. The classic, and most common, preexcitation syndrome is Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, which is estimated to occur in 0.1% to 0.4% of the population. Preexcitation in WPW syndrome is the result of rapid impulse conduction through an accessory pathway connecting the atria and ventricles and is described in detail in Chapter 45. This predisposes patients to atrioventricular (AV) reentrant tachycardia, atrial flutter, and atrial fibrillation. SCD can occur as a result of 1 : 1 conduction of an atrial tachycardia (namely atrial flutter or fibrillation) through the accessory pathway, resulting in a rapid ventricular rate.

Brugada Syndrome

Brugada syndrome is associated with syncope or sudden death at rest or during sleep, often in the setting of elevated body temperature (e.g., with fever or after vigorous exercise), or in the early morning. Presentation, therefore, can sometimes be confused with febrile seizures. Patients with this condition have normal QT intervals, ST-segment elevation with a “coved” appearance, and right ventricular conduction delay, although this pattern can be transient or absent (see Figure 48-1). As many as 50% of cases may be sporadic mutations. The other 50%, however, are associated with a positive family history, so special attention should be paid where there is a positive family history of syncope, abnormal ECG, or sudden death.

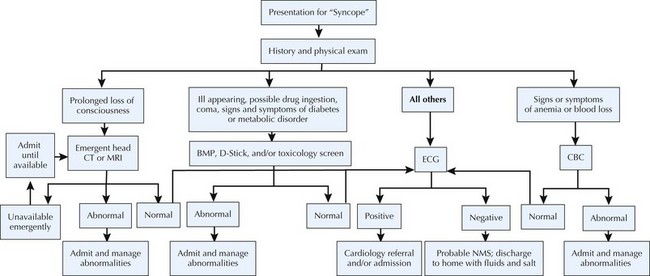

Evaluation And Diagnostic Approach

A thorough history and physical examination alone can suggest the diagnosis in the majority of cases of syncope (Figure 48-2). History of the present illness should include a detailed account of the event (including the duration, associated motor activity, and the circumstances surrounding recovery), triggers (including emotional, auditory, and exertional), and prodrome (including palpitations, chest pain, nausea or abdominal pain, diaphoresis, and lightheadedness). Past medical and family histories should focus on previous syncope and cardiac, neurologic, and psychiatric conditions. Family history should also include sudden or unexplained deaths, including sudden infant death syndrome, unexplained motor vehicle accidents, or a history of drowning or near drowning. Physical examination should include orthostatic vital signs and thorough cardiac and neurological examinations. Any patient with suspected cardiac cause should have an ECG as part of the evaluation. Patients with prolonged loss of consciousness, history of seizurelike movements, postepisode lethargy, or neurologic deficit should instead be evaluated with electroencephalography, head computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging; patients with suspected metabolic causes should be evaluated with a D-stick, basic metabolic panel, and toxicology screen; and patients with concerns for blood loss or signs of anemia should be evaluated with a complete blood cell count. Any female patient of childbearing age should also undergo a urine pregnancy test because the hemodynamic shifts associated with pregnancy predispose patients to syncope. If these tests do not reveal a diagnosis, most argue for ECG screening.

Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, et al. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006;296:1593-1601.

Goldenberg I, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Long QT syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2008;33:629-694.

Johnsrude CL. Current approach to pediatric syncope. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21(6):522-531.

Lewis DA, Dhala A. Syncope in the pediatric patient. The cardiologist’s perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46(2):205-219.

Maron BJ, Zipes DP. 36th Bethesda Conference: eligibility recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1312-1375.

Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308-1320.

Massin MM, Bourguignont A, Coremans C, et al. Syncope in pediatric patients presenting to an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2):223-228.

Steinberg LA, Knilans TK. Syncope in children: diagnostic tests have a high cost and low yield. J Pediatr. 2005;146(3):355-358.

Wieling W, Ganzeboom KS, Saul JP. Reflex syncope in children and adolescents. Heart. 2004;90(9):1094-1100.