Chapter 60

Syncope

1. What is the word syncope derived from?

2. What is the underlying mechanism causing syncope?

3. Cessation of cerebral blood flow of what duration causes syncope?

Cessation of cerebral blood flow for as short a period as 6 to 8 seconds can precipitate syncope.

4. What is the most common cause of syncope in the general population?

5. What are the most common causes of syncope in pediatric and young patients?

6. What is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes?

7. What are the common causes of syncope?

Neurocardiogenic: This is the most common cause of syncope in otherwise healthy persons, particularly younger persons. It is often precipitated by fear, anxiety, or other types of emotional distress. Its course is usually benign.

Neurocardiogenic: This is the most common cause of syncope in otherwise healthy persons, particularly younger persons. It is often precipitated by fear, anxiety, or other types of emotional distress. Its course is usually benign.

Orthostatic hypotension: Orthostatic hypotension results from venous pooling and decreased cardiac output and fall in blood pressure. It may be due to volume depletion, anemia or acute bleeding, peripheral vasodilators (most notoriously the α-adrenoceptor blockers used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy), or autonomic dysfunction (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, dysautonomia caused by central nervous system [CNS] disease).

Orthostatic hypotension: Orthostatic hypotension results from venous pooling and decreased cardiac output and fall in blood pressure. It may be due to volume depletion, anemia or acute bleeding, peripheral vasodilators (most notoriously the α-adrenoceptor blockers used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy), or autonomic dysfunction (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, dysautonomia caused by central nervous system [CNS] disease).

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity: This condition is suggested by syncope precipitated by neck movement, or by tight collars or ties. The diagnosis is made by carotid sinus massage (see Question 12).

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity: This condition is suggested by syncope precipitated by neck movement, or by tight collars or ties. The diagnosis is made by carotid sinus massage (see Question 12).

Cerebrovascular disease: Carotid artery stenosis usually leads to focal neurologic deficits rather that frank syncope (except perhaps in the very rare case of severe bilateral carotid artery disease, in which global cerebral hypoperfusion can occur). Vertebrobasilar disease is more likely to lead to syncope, although this is a rare cause of syncope in the general population.

Cerebrovascular disease: Carotid artery stenosis usually leads to focal neurologic deficits rather that frank syncope (except perhaps in the very rare case of severe bilateral carotid artery disease, in which global cerebral hypoperfusion can occur). Vertebrobasilar disease is more likely to lead to syncope, although this is a rare cause of syncope in the general population.

Tachyarrhythmias: Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and torsades de pointes are the most ominous cause of syncope. In patients with a history of prior myocardial infarction or those with significantly depressed left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (less than 30% to 35%), the presumptive cause of syncope is VT until proven otherwise. Polymorphic VT and torsades de pointes is the presumptive cause of syncope in those with prolonged QT intervals because of drugs or congenital long QT syndrome, and in those with Brugada syndrome (see Question 17). Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) may produce presyncope but does not usually produce overt syncope.

Tachyarrhythmias: Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and torsades de pointes are the most ominous cause of syncope. In patients with a history of prior myocardial infarction or those with significantly depressed left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (less than 30% to 35%), the presumptive cause of syncope is VT until proven otherwise. Polymorphic VT and torsades de pointes is the presumptive cause of syncope in those with prolonged QT intervals because of drugs or congenital long QT syndrome, and in those with Brugada syndrome (see Question 17). Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) may produce presyncope but does not usually produce overt syncope.

Bradyarrhythmias: Syncope may be caused by intermittent complete heart block. Sick sinus syndrome is a general term covering multiple disorders of the conduction system. Tachy-Brady syndrome is the more appropriate term used to describe patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation who, when the atrial fibrillation terminates, then have a several or more second period of asystole before normal sinus rhythm and ventricular depolarization resume.

Bradyarrhythmias: Syncope may be caused by intermittent complete heart block. Sick sinus syndrome is a general term covering multiple disorders of the conduction system. Tachy-Brady syndrome is the more appropriate term used to describe patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation who, when the atrial fibrillation terminates, then have a several or more second period of asystole before normal sinus rhythm and ventricular depolarization resume.

Structural-functional: Aortic stenosis is the most common structural cause of syncope in older patients. The dynamic obstruction that occurs in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (see Chapter 27) is the most common cause of structural-functional–mediated syncope in younger patients. Left atrial myxoma, causing functional mitral stenosis, is an extremely rare cause of syncope. Syncope can also occur with massive pulmonary embolism, which obstructs the pulmonary artery to such an extent that it compromises blood flow to the LV.

Structural-functional: Aortic stenosis is the most common structural cause of syncope in older patients. The dynamic obstruction that occurs in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (see Chapter 27) is the most common cause of structural-functional–mediated syncope in younger patients. Left atrial myxoma, causing functional mitral stenosis, is an extremely rare cause of syncope. Syncope can also occur with massive pulmonary embolism, which obstructs the pulmonary artery to such an extent that it compromises blood flow to the LV.

Box 60-1 lists the causes of syncope and loss of consciousness.

8. What are the important causes of ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VTs)?

Coronary artery disease (CAD). Acute ischemia or myocardial infarction (MI) may cause VT.

Coronary artery disease (CAD). Acute ischemia or myocardial infarction (MI) may cause VT.

Depressed LV ejection fraction (EF). Whether due to CAD or nonischemic, cardiomyopathy with depressed EF (<30%-35%) predisposes to VT.

Depressed LV ejection fraction (EF). Whether due to CAD or nonischemic, cardiomyopathy with depressed EF (<30%-35%) predisposes to VT.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Patients with HCM are at increased risk of VT, particularly if there is a history of syncope, familial history of sudden cardiac death, or markedly thickened ventricular septum (>30 mm).

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Patients with HCM are at increased risk of VT, particularly if there is a history of syncope, familial history of sudden cardiac death, or markedly thickened ventricular septum (>30 mm).

Prolonged QT interval. The QT interval may be prolonged due to drugs or may be seen in congenital QT prolongation (see Question 16). A prolonged QT interval predisposes to torsades de pointes.

Prolonged QT interval. The QT interval may be prolonged due to drugs or may be seen in congenital QT prolongation (see Question 16). A prolonged QT interval predisposes to torsades de pointes.

Brugada syndrome. Discussed later (see Question 17), this condition predisposes to polymorphic VT.

Brugada syndrome. Discussed later (see Question 17), this condition predisposes to polymorphic VT.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD). A rare condition in which there is fatty and fibrotic infiltration of the right ventricle.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD). A rare condition in which there is fatty and fibrotic infiltration of the right ventricle.

Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) VT. VT may originate from the RVOT. VT in this condition less commonly leads to death.

Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) VT. VT may originate from the RVOT. VT in this condition less commonly leads to death.

9. What is the approach to the patient with syncope?

A detailed history and physical examination, along with electrocardiogram (ECG) examination, can identify the presumptive cause of syncope in 40% to 50% of cases. Premonitory symptoms such as nausea or diaphoresis, especially in a younger person, or symptoms caused by anxiety, pain, or emotional distress, suggest neurocardiogenic syncope. Syncope during or immediately after urination, defecation, or certain other activities suggests situational syncope. Recent initiation of certain blood pressure–lowering medications, particularly α-adrenoceptor blockers (such as those used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy), raise suspicion for orthostatic hypotension, which can be confirmed on examination. A history of prior MI or depressed EF raises the concern for VT. Cardiac systolic murmurs suggest aortic stenosis or HCM. Table 60-1 gives the factors on history, physical examination, and ECG that may suggest a specific cause for the patient’s syncope.

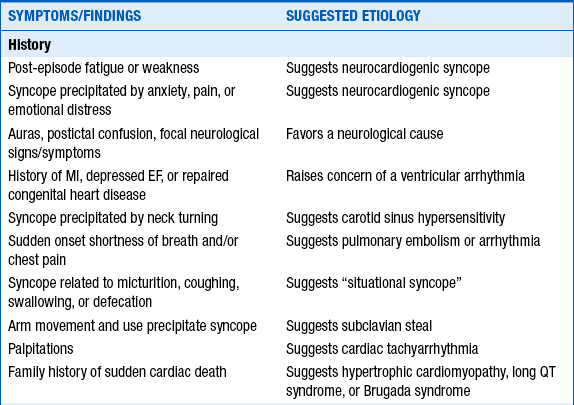

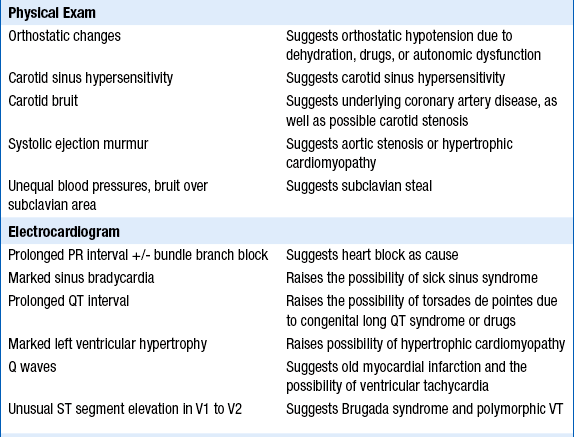

TABLE 60-1

SYMPTOMS AND FINDINGS OBTAINED ON THE HISTORY, PHYSICAL DIAGNOSIS, AND ELECTROCARDIOGRAM, AND THE ETIOLOGY FOR SYNCOPE THAT THEY SUGGEST

EF, Ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

10. How does one properly test for orthostatic hypotension?

Recommendations vary, but according to the ESC Guidelines on the Management of Syncope, one first has the patient lie supine for 5 minutes. Blood pressure is then measured 3 minutes after the patient stands, with subsequent blood pressure measurements each minute thereafter if the blood pressure falls and continues to fall compared with supine values. Orthostatic hypotension is defined as a 20 mm Hg or greater drop in systolic blood pressure or systolic blood pressure falling to less than 90 mm Hg. Some other experts also consider falls of diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg or more or increases in heart rate of 20 beats/min or more as criteria to diagnose orthostatic hypotension.

11. What other testing can be performed when the cause of syncope remains unclear?

12. During carotid sinus massage, what is considered a diagnostic response?

13. What is a tilt table test?

14. How should one decide between ordering a Holter monitor, an event or ambulatory monitor, or an implantable loop monitor?

15. Should a shotgun neurologic evaluation, including computed tomography (CT) scan, carotid ultrasound, and electroencephalogram, be ordered in all patients with syncope?

No. True syncope (or loss of consciousness) is an unusual manifestation of neurologic syncope (excluding causes such as reflex, situational, or neurocardiogenic syncope and dysautonomia). In one report, electroencephalogram provided diagnostic information in less than 2% of cases of syncope, and almost all those patients had a history of seizures or symptoms suggesting seizure. Neurologic workup should only be undertaken if a neurologic cause is suggested by the history or physical examination. TIAs usually do not cause syncope. Carotid disease and stroke more likely lead to focal neurologic deficits than to global neurologic ischemia and syncope (the rare exception being severe bilateral carotid artery disease). Severe bilateral vertebrobasilar disease can cause syncope, but is not easily diagnosed by screening studies. Importantly, cerebral hypoperfusion caused by ventricular tachycardia can result in seizure-like activity, and the report by family members or other witnesses of the event of “seizure-like” activity in the patient should not cause one to be misled toward a search for neurologic causes based on this alone.

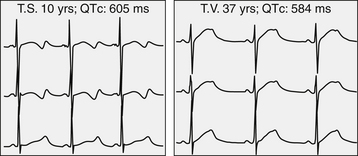

Long QT syndrome is characterized by a corrected QT interval (QTc) of greater than 450 ms (Fig. 60-1). The QT interval is prolonged because of delayed repolarization as a result of a genetic defect in either potassium or sodium channels. Syncope in patients in long QT syndrome likely is due to torsade des pointes. The onset of symptoms most commonly occurs during the first two decades of life. The risk of developing syncope or sudden cardiac death increases with QTc, with lifetime risks of approximately 5% in those with QTc less than 440 ms, but 50% in those with QTc more than 500 ms. Patients with long QT syndrome should be referred to electrophysiologists for further evaluation and treatment, which may include medicines or placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

Figure 60-1 Typical electrocardiogram of two long QT syndrome patients showing QT interval prolongation and T wave morphologic abnormalities. (From Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.) QTc, Corrected QT interval.

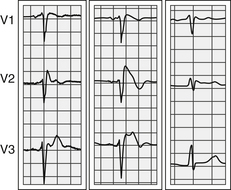

Brugada syndrome is a disorder of sodium channels, resulting in sometimes intermittent unusual ST segment elevation in leads V1 through V3, as well as a right bundle branch block–like pattern (Fig. 60-2). Such patients are susceptible to developing polymorphic VT. Patients with suspected Brugada syndrome should be referred for specialized cardiac evaluation and a probable placement of an ICD.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Brignole, M., Alboni, P., Benditt, D.G., et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope-update. Executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2054–2072.

2. Calkins, H., Zipes, D.P. Hypotension and syncope. In: Libby P., Bonow R.O., Mann D.L., Zipes D.P., eds. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. ed 8. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008:975–984.

3. Morag, R. Syncope. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/811669-overview. Accessed March 26, 2013

4. Fogel, R.I., Varma, J. Approach to the patient with syncope. In: Levine G.N., Mann D.L., eds. Primary care provider’s guide to cardiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

5. Higginson, L.A. Syncope. Available at http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular_disorders/symptoms_of_cardiovascular_disorders/syncope.html. Accessed March 26, 2013

6. Kapoor, W.P. Syncope. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2054–2072.

7. Priori, S.G., Napolitano, C., Schwartz, P.J. Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias. In: Libby P., Bonow R.O., Mann D.L., Zipes D.P., eds. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. ed 8. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008:101–110.

8. Strickberger, S.A., Benson, D.W., Biaggioni, I., et al. AHA/ACCF scientific statement on the evaluation of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:473–484.