Chapter 43 SYNCOPE

Causes of Syncope

Key Historical Features

Situation in which syncope occurred (on standing, in a fearful situation, during micturition, with coughing, with exertion)

Situation in which syncope occurred (on standing, in a fearful situation, during micturition, with coughing, with exertion)

Activities leading up to the event

Activities leading up to the event

Prodromal symptoms (lightheadedness, warmth, nausea, sweating)

Prodromal symptoms (lightheadedness, warmth, nausea, sweating)

Associated cardiac symptoms (chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath)

Associated cardiac symptoms (chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath)

Associated neurologic symptoms (focal neurologic symptoms, headache, diplopia)

Associated neurologic symptoms (focal neurologic symptoms, headache, diplopia)

Witnessed events (tonic/clonic movements, tongue biting, urinary incontinence)

Witnessed events (tonic/clonic movements, tongue biting, urinary incontinence)

If witnessed, characterization of the patient’s appearance during and immediately following the episode

If witnessed, characterization of the patient’s appearance during and immediately following the episode

Medical history, particularly:

Medical history, particularly:

Key Physical Findings

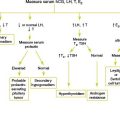

Suggested Work-up

| ECG | To identify abnormalities that may suggest an underlying cardiac cause for the syncope. Important findings include a long QT interval, preexcitation, evidence of conduction disorders, signs of coronary artery disease, or left ventricular hypertrophy that may be associated with ventricular tachycardia. |

| Complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and glucose | Indicated when an underlying disorder is suspected as a potential cause of syncope |

| Pregnancy test | Should be considered in adolescent females |

Additional Work-up

| Cardiology consultation and echocardiogram | Should be obtained if a heart murmur is appreciated, a family history of sudden death or cardiomyopathy exists, or the ECG is at all suspicious |

| Holter monitoring or telemetry monitoring | Should be considered in patients with a history of palpitations associated with syncope. Also recommended for patients with known or suspected cardiac disease or a suspected arrhythmic cause of syncope. |

| Treadmill exercise stress test | Should be considered if the syncopal event is associated with exercise |

| Tilt-table testing | May be useful in patients with recurrent unexplained syncope with a suspected neurocardiogenic cause. May also be useful in patients without cardiac disease or in whom cardiac testing has been negative. |

| Cardiac catheterization and electrophysiologic testing | May be indicated for patients with primary dysrhythmias and patients with preexcitation syndromes such as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and in patients with a suspected bradyarrhythmic cause for syncope |

| Electroencephalogram (EEG) and neurologic consultation | Indicated in patients exhibiting prolonged loss of consciousness, seizure activity, and a postictal phase of lethargy or confusion. EEG is indicated only when seizure is suspected because the positive yield of EEG is otherwise very low. |

| 24-hour Holter monitor or a loop-recording event monitor | May be useful in patients with a history of palpitations associated with syncope to help capture the cardiac rhythm |

| Computed tomography (CT) | CT scanning of the head has a relatively low yield in patients with syncope and is not routinely indicated. It is recommended in patients with focal neurologic symptoms and signs. It may be performed in patients with seizure activity and head trauma to rule out intracranial hemorrhage. |

| Psychiatric evaluation | Recommended for patients with recurrent unexplained syncope if there is no cardiac disease or if the cardiac evaluation is negative. Young patients and patients with many prodromal symptoms are at higher risk of having an underlying psychiatric disease associated with their episodes of syncope. |

| Admission to the hospital for observation with continuous ambulatory ECG and EEG monitoring | May be indicated if syncope is reported to be occurring several times a day every day. Video surveillance may be included if factitious or induced illness is suspected. |

1. Abboud F.M. Neurocardiogenic syncope. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1117–1120.

2. Atkins D., et al. Syncope and orthostatic hypotension. Am J Med. 1991;91:179–185.

3. Calkins H. Pharmacologic approaches to therapy for vasovagal syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:20Q-25Q.

4. Cunningham R., Mikhail M.G. Management of patients with syncope and cardiac arrhythmias in an emergency department observation unit. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:105–121.

5. Davis T.L., Freemon F.R. Electroencephalography should not be routine in the evaluation of syncope in adults. Arch Inter Med. 1990;150:2027–2029.

6. Di Girolamo E., et al. Effects of paroxetine hydrochloride, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on refractory vasovagal syncope: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1227–1230.

7. Kaufmann H. Neurally mediated syncope: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurology. 1995;45(suppl 5):S12-S18.

8. Kapoor W.N. Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1856–1862.

9. Kelly A.M., et al. Breath-holding spells associated with significant bradycardia; successful treatment with permanent pacemaker implantation. Pediatrics. 2001;108:698–702.

10. Lewis D.A., Dhala A. Syncope in the pediatric patient: the cardiologist’s perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:205–219.

11. Linzer M., et al. Diagnosing syncope: Part 1: value of history, physical examination and electrocardiography. Clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989–996.

12. Linzer M., et al. Diagnosing syncope: Part 2: unexplained syncope. Clinical efficacy project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:76–86.

13. Mahanonda N., et al. Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral atenolol in patients with unexplained syncope and positive upright tilt table test results. Am Heart J. 1995;130:1250–1253.

14. McLeod K.A. Syncope in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:350–353.

15. Munro N.C., et al. Incidence of complications after carotid sinus massage in older patients with syncope. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1248–1251.

16. Rodriguez-Nunez A., et al. Cerebral syncope in children. J Pediatr. 2000;136:542–544.

17. Sapin S.O. Autonomic syncope in pediatrics: a practice-oriented approach to classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43:17–23.

18. Schnipper J.L., Kapoor W.N. Diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with syncope. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:423–456.

19. Strckberger S.A., et al. AHA/ACCF scientific statement on the evaluation of syncope: from the American Heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the American Autonomic Society. Circulation. 2006;113:316–327.

20. Sutton R., et al. Dual chamber pacing in the treatment of neurally mediated positive cardioinhibitory syncope: pacemaker versus no therapy—a multicenter randomized study. The Vasovagal Syncope International Study (VASIS) Investigators. Circulation. 2000;102:294–299.

21. Sutton R., et al. Proposed classification for tilt induced vasovagal syncope. Eur J Pacing Electrophysiol. 1992;3:180–183.

22. Ward C.R., et al. Midodrine: a role in the management of neurocardiogenic syncope. Heart. 1998;79:45–49.

23. Weimer L.H., et al. Syncope and orthostatic intolerance for the primary care physician. Primary Care Clin Office Pract. 2004;31:175–199.

24. Zeng C., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral enalapril in patients with neurally mediated syncope. Am Heart J. 1998;136:852–858.

25. Zimetbaum P., et al. Utility of patient-activated cardiac event recorders in general clinical practice. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:371–372.