CHAPTER 12 Symptoms of Esophageal Disease

Symptoms related to the esophagus are among the most common in general medical as well as gastroenterologic practice. For example, dysphagia becomes more common with aging and affects up to 15% of persons age 65 or older.1 Heartburn, regurgitation, and other symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) also are common. A survey of healthy subjects in Olmsted County, Minnesota, found that 20% of persons, regardless of gender or age, experienced heartburn at least weekly.2 Mild symptoms of GERD rarely indicate severe underlying disease but must be addressed, especially if they have occurred for many years. Frequent or persistent dysphagia or odynophagia suggests an esophageal problem that necessitates investigation and treatment. Other less specific symptoms of possible esophageal origin include globus sensation, chest pain, belching, hiccups, rumination, and extraesophageal complaints, such as wheezing, coughing, sore throat, and hoarseness, especially if other causes have been excluded. A major challenge in the evaluation of esophageal symptoms is that the degree of esophageal damage often does not correlate well with the patient’s or physician’s impression of symptom severity. This is a particular problem in older patients, in whom the severity of gastroesophageal reflux–induced injury to the esophageal mucosa is increased despite an overall decrease in the severity of symptoms.3

DYSPHAGIA

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The inability to swallow is caused by a problem with the strength or coordination of the muscles required to move material from the mouth to the stomach or by a fixed obstruction somewhere between the mouth and the stomach. Occasional patients may have a combination of the two processes. The oropharyngeal swallowing mechanism and the primary and secondary peristaltic contractions of the esophageal body that follow usually transport solid and liquid boluses from the mouth to the stomach within 10 seconds (see Chapter 42). If these orderly contractions fail to develop or progress, the accumulated bolus of food distends the esophageal lumen and causes the discomfort that is associated with dysphagia. In some patients, particularly older adults, dysphagia is the result of low-amplitude primary or secondary peristaltic activity that is insufficient to clear the esophagus. Other patients have a primary or secondary motility disorder that grossly disturbs the orderly contractions of the esophageal body. Because these motor abnormalities may not be present with every swallow, dysphagia may wax and wane (see Chapter 42).

Mechanical narrowing of the esophageal lumen may interrupt the orderly passage of a food bolus despite adequate peristaltic contractions. Symptoms vary with the degree of luminal obstruction, associated esophagitis, and type of food ingested. Although minimally obstructing lesions cause dysphagia only with large, poorly chewed boluses of foods such as meat and dry bread, lesions that obstruct the esophageal lumen completely lead to symptoms with solids and liquids. GERD may produce dysphagia related to an esophageal stricture, but some patients with GERD clearly have dysphagia in the absence of a demonstrable stricture, and perhaps even without esophagitis.4 Abnormal sensory perception in the esophagus may lead to the perception of dysphagia, even when the bolus has cleared the esophagus. Because some normal subjects experience the sensation of dysphagia when the distal esophagus is distended by a balloon, as well as by other intraluminal stimuli, an aberration in visceral perception could explain dysphagia in patients who have no definable cause.5 This mechanism also may apply to the amplification of symptoms in patients with spastic motility disorders, in whom the frequency of psychiatric disorders is increased.6

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND APPROACH

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Recurrent bouts of pulmonary infection may reflect spillover of food into the trachea because of inadequate laryngeal protection. Hoarseness may result from recurrent laryngeal nerve dysfunction or intrinsic muscular disease, both of which cause ineffective vocal cord movement. Weakness of the soft palate or pharyngeal constrictors causes dysarthria and nasal speech as well as pharyngonasal regurgitation. Swallowing associated with a gurgling noise may be described by patients with Zenker’s diverticulum. Finally, unexplained weight loss may be the only clue to a swallowing disorder; patients avoid eating because of the difficulties encountered. Potential causes of oropharyngeal dysphagia are shown in Table 12-1.

| Neuromuscular Causes* |

CNS, central nervous system; UES, upper esophageal sphincter.

* Any disease that affects striated muscle or its innervation may result in dysphagia.

† Many manometric disorders (hypertensive and hypotensive UES, abnormal coordination, and incomplete UES relaxation) have been described, although their true relationship to dysphagia is often unclear.

Esophageal Dysphagia

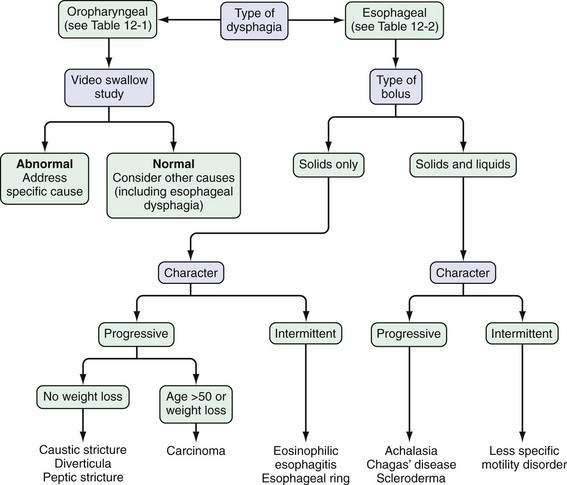

On the basis of these answers, distinguishing the several causes of esophageal dysphagia (Table 12-2) as a mechanical or a neuromuscular defect and postulating the specific cause are often possible (Fig. 12-1).

| Motility (Neuromuscular) Disorders |

| Primary Disorders |

LES, lower esophageal sphincter.

Patients who report dysphagia with solids and liquids are more likely to have an esophageal motility disorder than mechanical obstruction. Achalasia is the prototypical esophageal motility disorder in which, in addition to dysphagia, many patients complain of bland regurgitation of undigested food, especially at night, and of weight loss. By contrast, patients with spastic motility disorders such as diffuse esophageal spasm may complain of chest pain and sensitivity to hot or cold liquids. Patients with scleroderma of the esophagus usually have Raynaud’s phenomenon and severe heartburn. In these patients, mild complaints of dysphagia can be caused by a motility disturbance or esophageal inflammation, but severe dysphagia almost always signals the presence of a peptic stricture (see Chapters 35 and 43).

In patients who report dysphagia only after swallowing solid foods and never with liquids alone, a mechanical obstruction is suspected. A luminal obstruction of sufficiently high grade, however, may be associated with dysphagia for solids and liquids. If food impaction develops, the patient frequently must regurgitate for relief. If a patient continues to drink liquid after the bolus impaction, large amounts of that liquid may be regurgitated. In addition, hypersalivation is common during an episode of dysphagia, thereby providing even more liquid to regurgitate. Episodic and nonprogressive dysphagia without weight loss is characteristic of an esophageal web or a distal esophageal (Schatzki) ring. The first episode typically occurs during a hurried meal, often with alcohol. The patient notes that the bolus of food sticks in the lower esophagus; it often can be passed by drinking large quantities of liquids. Many patients finish the meal without difficulty after the obstruction is relieved. The offending food frequently is a piece of bread or steak—hence the term steakhouse syndrome.7 Initially, an episode may not recur for weeks or months, but subsequent episodes may occur frequently. Daily dysphagia, however, is likely not caused by a lower esophageal ring (see Chapter 41).

If solid food dysphagia is clearly progressive, the differential diagnosis includes peptic esophageal stricture and carcinoma. Benign esophageal strictures develop in some patients with GERD. Most of these patients have a long history of associated heartburn. Weight loss seldom occurs in patients with a benign lesion, because these patients have a good appetite and convert their diet to high-calorie soft and liquid foods to maintain weight (see Chapter 43). Patients with carcinoma differ from those with peptic stricture in several ways. As a group, the patients with carcinoma are older and present with a history of rapidly progressive dysphagia. They may or may not have a history of heartburn, and heartburn may have occurred in the past but not the present. Most have anorexia and weight loss (see Chapter 46). True dysphagia may be seen in patients with pill, caustic, or viral esophagitis; however, the predominant complaint of patients with these acute esophageal injuries is usually odynophagia. Patients may present with food bolus impaction, and eosinophilic esophagitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of all patients (particularly those who are young) who present with dysphagia (see Chapter 27).8

After a focused history of the patient’s symptoms is obtained, a barium radiograph, including a solid bolus challenge, is often advocated as the first test. Alternatively, many experts have advocated endoscopy as the first test, especially in patients with intermittent dysphagia for solid food suggestive of a lower esophageal ring or with pronounced reflux symptoms. The choice of the initial test should be based on local expertise and the preference of the individual health care provider. If the barium examination demonstrates an obstructive lesion, endoscopy is usually done for confirmation and biopsy. Endoscopy also permits dilation of strictures, rings, and neoplasms. Empirical dilation of the esophagus is often performed in patients with a suggestive history and normal endoscopic examination,9 but the safety and efficacy of this approach have been questioned.10 If the barium examination is normal, esophageal manometry is often performed to look for a motility disorder. Some patients with reflux symptoms and dysphagia, a normal barium study or endoscopy, or both, will respond to a trial of gastric acid suppressive therapy.

ODYNOPHAGIA

Like dysphagia, odynophagia, or painful swallowing, is specific for esophageal involvement. Odynophagia may range from a dull retrosternal ache on swallowing to a stabbing pain with radiation to the back so severe that the patient cannot eat or even swallow his or her own saliva. Odynophagia usually reflects an inflammatory process that involves the esophageal mucosa or, in rare instances, the esophageal muscle. The most common causes of odynophagia include caustic ingestion, pill-induced esophagitis, radiation injury, and infectious esophagitis (Candida, herpesvirus, and cytomegalovirus; Table 12-3). In these diseases, dysphagia also may be present, but pain is the dominant complaint. Odynophagia is an infrequent complaint of patients with GERD and, when present, usually is associated with severe ulcerative esophagitis. In rare cases, a nonobstructive esophageal carcinoma can produce odynophagia. Because many of the diseases that cause odynophagia have associated symptoms and signs, a carefully taken history can often lead directly to a diagnosis. For example, a teenager who takes tetracycline for acne and in whom odynophagia develops most likely has pill dysphagia, an immunocompromised patient with odynophagia is likely to have an infectious cause, and a patient with GERD is likely to have severe peptic esophagitis. On the other hand, gastrointestinal endoscopy to visualize and obtain biopsies of the esophageal mucosa is required to confirm a specific diagnosis in most patients with odynophagia.

| Caustic Ingestion |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

GLOBUS SENSATION

Globus sensation is a feeling of a lump or tightness in the throat, unrelated to swallowing. Up to 46% of the general population experience globus sensation at one time or another.11 The sensation can be described as a lump, tightness, choking, or strangling feeling, as if something is caught in the throat. Globus sensation is present between meals, and swallowing of solids or large liquid boluses may give temporary relief. Frequent dry swallowing and emotional stress may worsen this symptom. Globus sensation should not be diagnosed in the presence of dysphagia or odynophagia.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND APPROACH

The detection of physiologic and psychological abnormalities in patients with globus sensation has been inconsistent and controversial. Although frequently suggested, manometrically identifiable UES dysfunction has not been identified directly as the cause of globus sensation. The UES also does not appear to be hyperresponsive to esophageal distention, acidification, or mental stress.12 Furthermore, esophageal distention can cause globus sensation unrelated to any rise in UES pressure, and stress can induce an increase in UES pressure that is not associated with globus sensation in normal subjects and in patients who complain of globus sensation. Heartburn has been reported in up to 90% of patients with globus sensation,13 yet documentation of esophagitis or abnormal gastroesophageal reflux by esophageal pH monitoring is found in fewer than 25%. Balloon distention of the esophagus produces globus sensation at lower balloon volumes in globus sufferers than in controls; this finding suggests that the perception of esophageal stretch may be heightened in some patients with globus sensation.

Psychological factors may be important in the genesis of globus sensation. The most common associated psychiatric diagnoses include anxiety, panic disorder, depression, hypochondriasis, somatization, and introversion.14 Indeed, globus sensation is the fourth most common symptom in patients with somatization disorders.15 A combination of biological factors, hypochondriacal traits, and learned fear after a choking episode provides a framework for misinterpretation of the symptoms and intensifies the symptoms of globus or the patient’s anxiety.16

The approach to globus sensation involves excluding a more sinister underlying disorder and then offering symptom-driven therapy. A nasal endoscopy to rule out pharyngeal pathology and a barium swallow to rule out a fixed pharyngeal lesion are often helpful.17 If these studies are negative, trials of acid suppression with a proton pump inhibitor, medications directed at visceral sensitivity, or other psychologically based therapies are reasonable. If a patient has heartburn, then acid suppressive therapy is the first step, but reflux may be the cause of globus sensation, even in the absence of heartburn. A trial of a proton pump inhibitor (usually given twice daily, before meals) is diagnostic and therapeutic in some patients. Ambulatory reflux monitoring may show acid or nonacid reflux in some patients.18 Alternatively, if the patient has obvious anxiety and has already failed a trial of acid suppression, therapy directed toward the psychological component of the problem should be considered.

HICCUPS

The symptom of hiccups (hiccoughs, singultus) is caused by a combination of diaphragmatic contraction and glottic closure. Therefore, it is not classically an esophageal symptom but is a common complaint in primary care and gastroenterology. Most cases of hiccups are idiopathic, but the symptom has been associated with many conditions (trauma, masses, infections) that affect the central nervous system, thorax, or abdomen. Gastrointestinal causes include GERD, achalasia, gastropathies, and peptic ulcer. Hiccups associated with uremia may be particularly difficult to control. They often occur after a large meal. Because most cases are self-limited, intervention is not usually required. The evaluation of chronic or difficult cases should include selected tests to exclude esophageal, thoracic, or systemic diseases. Because GERD has been associated with hiccups, a trial of acid suppressive therapy may be reasonable in some patients.19 Many agents have been used to suppress hiccups with varying success, including chlorpromazine, nifedipine, haloperidol, phenytoin, metoclopramide, baclofen, and gabapentin.20 Alternative modalities, including acupuncture, also have been tried in refractory cases.21

CHEST PAIN OF ESOPHAGEAL ORIGIN

Chest pain of esophageal origin may be indistinguishable to patients and their health care providers from angina pectoris. The esophagus and heart are anatomically adjacent and share innervation. In fact, once cardiac disease is excluded, esophageal disorders are probably the most common causes of chest pain. Of the approximately 500,000 patients in the United States who undergo coronary angiography yearly for presumed cardiac pain, almost 30% have normal epicardial coronary arteries; of these patients, esophageal diseases may account for the symptoms in 18% to 56%.22

Esophageal chest pain usually is described as a squeezing or burning substernal sensation that radiates to the back, neck, jaw, or arms. Although it is not always related to swallowing, the pain can be triggered by ingestion of hot or cold liquids. It may awaken the patient from sleep and can worsen during periods of emotional stress. The duration of pain ranges from minutes to hours, and the pain may occur intermittently over several days. Although the pain can be severe, causing the patient to become ashen and to perspire, it often abates spontaneously and may be eased with antacids. Occasionally, the pain is so severe that narcotics or nitroglycerin are required for relief. Close questioning reveals that most patients with chest pain of esophageal origin have other esophageal symptoms; however, chest pain is the only esophageal complaint in about 10% of cases.23

The clinical history does not enable the physician to distinguish reliably between a cardiac and esophageal cause of chest pain. In fact, gastroesophageal reflux may be triggered by exercise24 and cause exertional chest pain that mimics angina pectoris, even during treadmill testing. Symptoms suggestive of esophageal origin include pain that continues for hours, retrosternal pain without lateral radiation, pain that interrupts sleep or is related to meals, and pain relieved with antacids. The presence of other esophageal symptoms helps establish an esophageal cause of pain. As many as 50% of patients with cardiac pain, however, also have one or more symptoms of esophageal disease.25 Furthermore, relief of pain with sublingual nitroglycerin has been shown not to be specific for a coronary origin of pain.26 Cardiac and esophageal disease increase in frequency as people grow older, and both problems may not only coexist but also interact to produce chest pain.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND APPROACH

The specific mechanisms that produce esophageal chest pain are not well understood. Chest pain that arises from the esophagus has commonly been attributed to the stimulation of chemoreceptors (by acid, pepsin, or bile) or mechanoreceptors (by distention or spasm); thermoreceptors (stimulated by cold) also may be involved. Gastroesophageal reflux causes chest pain primarily through acid-sensitive esophageal chemoreceptors (see later). Acid-induced dysmotility may be a cause of esophageal pain. Older studies have shown that perfusion of acid into the esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux increases the amplitude and duration of esophageal contractions and induces simultaneous and spontaneous contractions, with the occurrence of pain.27 Diffuse esophageal spasm also has been demonstrated during spontaneous acid reflux. Subsequent studies with modern equipment have shown that such changes in motility are rare.28 In addition, studies using 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH and motility monitoring have shown that the association between abnormal motility and pain is uncommon, and that spontaneous acid-induced chest pain is rarely associated with abnormalities in esophageal motility.29,30

Patients with chest pain suspected to be esophageal in origin have an increased frequency of esophageal contractions of high amplitude and a slightly increased frequency of simultaneous contractions when compared with a normal control population.31 In addition, intraluminal ultrasound has been able to identify abnormal sustained contractions of the longitudinal smooth muscle in a subset of patients with chest pain.32 How these contractions cause pain is unknown. One possible explanation is that pain occurs when high intramural esophageal tension resulting from altered motility inhibits blood flow to the esophagus for a critical period of time (i.e., myoischemia). MacKenzie and coworkers have found that rates of esophageal rewarming are decreased after infusions of cold water into the esophagus of patients with symptomatic esophageal motility disorders as compared with age-matched controls.33 Because the rate of rewarming after cold water infusion in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon correlates directly with blood flow, the authors theorized that esophageal ischemia is the cause of the reduced rate of rewarming. None of the patients with a symptomatic esophageal motility disorder, however, experienced chest pain during the study. Furthermore, the extensive arterial and venous blood supply to the esophagus makes it unlikely that blood flow is compromised after even the most abnormal esophageal contractions. Complicating the relationship between esophageal chest pain and abnormal esophageal contractions is the consistent observation that most of these patients are asymptomatic when the contraction abnormalities are identified. In addition, amelioration of chest pain does not correlate predictably with reduction in the amplitude of esophageal contractions.34 The possibility exists that chest pain–associated motility changes represent an epiphenomenon of a chronic pain syndrome rather than the direct cause of the pain.

Other potential causes of esophageal chest pain include excitation of temperature receptors and luminal distention. The ingestion of hot or cold liquids can produce severe chest pain. This association was previously thought to be related to esophageal spasm, but subsequent studies have shown that cold-induced pain produces esophageal aperistalsis and dilatation, not spasm.35 This observation suggests that the cause of esophageal chest pain may be activation of stretch receptors by acute distention. Esophageal distention and pain are experienced during an acute food impaction, drinking of carbonated beverages (in some patients), and dysfunction of the belch reflex.36 In susceptible persons, esophageal chest pain can be reproduced by distention of an esophageal balloon to volumes lower than those that produce pain in asymptomatic persons.37 Therefore, altered pain perception may contribute to the patient’s reaction to a painful stimulus. Panic disorder is a commonly overlooked coexisting condition in patients with chest pain38 and should be sought specifically during history taking. The observation that anxiolytics and antidepressants can raise pain thresholds, as well as improve mood states, may explain why these medications may improve esophageal chest pain in the absence of manometric changes,39,40

Insufficiency of coronary blood flow with normal-appearing epicoronary arteries (microvascular angina) has been suggested as a cause of chest pain in some patients.41 Diagnosing microvascular angina on the basis of a therapeutic trial is difficult because the medications reported to improve this condition also have effects on the esophagus; however, the prognosis of patients with microvascular angina is thought to be good.

The recognition that chest pain is often associated with GERD has been a major advance in our understanding of esophageal chest pain. Ambulatory pH testing can document pathologic amounts of acid reflux or a correlation between acid reflux and chest pain in up to 50% of patients in whom a cardiac cause has been excluded.42 In addition, a trial of therapy with a proton pump inhibitor produces symptomatic improvement in many such patients.43 The association between chest pain and GERD is easy to recognize when the patient has coexisting reflux symptoms but not so clear when typical reflux symptoms are absent. A 10- to 14-day trial of an oral proton pump inhibitor taken twice daily has been shown to be sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of esophageal chest pain when compared with ambulatory intraesophageal pH testing (see later).44 If a patient fails this trial, the next practical approach may be a trial of agents such as imipramine or trazodone that raise the pain threshold. Some authorities recommend esophageal testing with stationary manometry at this point to exclude a motility disorder and ambulatory pH testing to exclude reflux unresponsive to the initial trial of the proton pump inhibitor therapy. The advent of a tube-free system for reflux monitoring allows a longer and more comfortable monitoring period, which increases the likelihood of observing a correlation between pain and an acid event.45 If reflux is confirmed by ambulatory pH testing, an additional trial of acid suppressive therapy is warranted. If a spastic motility disorder is discovered on manometry, an attempt at lowering esophageal pressure with nitrates or a calcium channel blocker is appropriate (see Chapter 42).

HEARTBURN AND REGURGITATION

Heartburn (pyrosis) is one of the most common gastrointestinal complaints in Western populations.46 In fact, it is so common that many people assume it to be a normal part of life and fail to report the symptom to their health care providers. They seek relief with over-the-counter antacids, which accounts for most of the $1 billion/year sales of these nonprescription drugs. Despite its high prevalence, the term heartburn is frequently misunderstood. It has many synonyms, including indigestion, acid regurgitation, sour stomach, and bitter belching. The physician should listen for these descriptors if the patient does not volunteer a complaint of heartburn. A study from Europe has suggested that using a word-picture description of “a burning feeling rising from the stomach or lower chest up toward the neck” increases the ability to identify patients with reflux.47 The burning sensation often begins inferiorly and radiates up the entire retrosternal area to the neck, occasionally to the back, and rarely into the arms. Heartburn caused by acid reflux may be relieved, albeit only transiently, by the ingestion of antacids, baking soda, or milk. Interestingly, the severity of esophageal damage (esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus) does not correlate with the severity of heartburn (e.g., patients with severe heartburn may have a normal-appearing esophagus, and those with severe esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus may, at times, have mild or even no symptoms; see Chapters 43 and 44).48

Heartburn is most frequently noted within one hour after eating, particularly after the largest meal of the day. Sugars, chocolate, onions, carminatives, and foods high in fats may aggravate heartburn by decreasing lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Other foods commonly associated with heartburn—including citrus products, tomato-based foods, and spicy foods—irritate the inflamed esophageal mucosa because of acidity or high osmolarity.49 Beverages, including citrus juices, soft drinks, coffee, and alcohol, also may cause heartburn. Many patients have exacerbation of heartburn if they retire shortly after a late meal or snack, and others say that their heartburn is more pronounced while they lie on their right side.50 Weight gain frequently results in the development of new GERD symptoms and in the worsening of GERD symptoms in patients with preexisting symptoms.51

Activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, including bending over, straining at stool, lifting heavy objects, and performing isometric exercises, may aggravate heartburn. Running also may aggravate heartburn, and stationary bike riding may be a better exercise for those with GERD.52 Because nicotine and air swallowing relax LES pressure, cigarette smoking exacerbates the symptoms of reflux.53 Emotions such as anxiety, fear, and worry may exacerbate heartburn by lowering visceral sensitivity thresholds rather than by increasing the amount of acid reflux.54,55 Some heartburn sufferers complain that certain drugs may initiate or exacerbate their symptoms by reducing LES pressure and peristaltic contractions (e.g., theophylline, calcium channel blockers) or by irritating the inflamed esophagus (e.g., aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bisphosphonates).

Heartburn may be accompanied by the appearance of fluid in the mouth, either a bitter acidic material or a salty fluid. Regurgitation describes return of bitter acidic fluid into the mouth and, at times, the effortless return of food, acid, or bilious material from the stomach. Regurgitation is more common at night or when the patient bends over. The absence of nausea, retching, and abdominal contractions suggests regurgitation rather than vomiting. Water brash is an uncommon and frequently misunderstood symptom that should be used to describe the sudden filling of the mouth with clear, slightly salty fluid. This fluid is not regurgitated material but is secreted from the salivary glands as part of a protective, vagally mediated reflex from the distal esophagus.56 Regurgitation and symptoms similar to water brash can occur in patients with achalasia, who may be misdiagnosed as having GERD.

Regurgitation must be distinguished from the syndrome of rumination (see Chapter 14). Rumination is a clinical diagnosis and is best described by the Rome III diagnostic criteria. Patients must have persistent or recurrent regurgitation (not preceded by retching) of recently ingested food into the mouth, with subsequent remastication and swallowing. Supportive criteria include absence of nausea, cessation of the process when the regurgitated material becomes acidic, and content consisting of recognizable food with a pleasant taste in the regurgitant.57 Rumination is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion when there is clinical suspicion.

Nocturnal reflux symptoms have particular significance. In a survey of patients with frequent reflux symptoms, 74% reported nocturnal symptoms.58 These nighttime symptoms interrupt sleep and health-related quality of life to a greater degree than daytime reflux symptoms alone. Patients who have prolonged reflux episodes at night also are at increased risk of complications of GERD, including severe reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND APPROACH

The physiologic mechanisms that produce heartburn remain poorly understood. Although the reflux of gastric acid is most commonly associated with heartburn, the same symptom may be elicited by esophageal balloon distention,59 reflux of bile salts,60 and acid-induced motility disturbances. The best evidence that the pain mechanism is probably related to the stimulation of mucosal chemoreceptors is the sensitivity of the esophagus to acid that is perfused into the esophagus or acid reflux, demonstrated by monitoring of pH. The location of these chemoreceptors is not known. One suggestion is that the esophagus is sensitized by repeated acid exposure, resulting in the production of symptoms from smaller boluses after repeated exposure to acid. This hypersensitivity has been reported to resolve with acid suppressive therapy.61

The correlation between discrete episodes of acid reflux and symptoms, however, is poor. For example, postprandial gastroesophageal reflux is common in healthy people, but symptoms are uncommon. Intraesophageal pH monitoring of patients with endoscopic evidence of esophagitis typically shows excessive periods of acid reflux, but fewer than 20% of these reflux episodes are accompanied by symptoms.62 Moreover, one third of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, the most extreme form of GERD, are acid-insensitive.63 As patients age, their sensitivity to esophageal acid seems to decline; this finding may explain the common observation that mucosal damage is fairly severe but symptoms are minimal in older patients.64 Therefore, the development of symptoms must require more than esophageal contact with acid. Mucosal disruption and inflammation may be a contributing factor but, on endoscopy, the esophagus appears normal in most symptomatic patients. Other factors that possibly influence the occurrence of heartburn include the acid clearance mechanism, salivary bicarbonate concentration, volume of acid refluxed, as measured by the duration and proximal extent of reflux episodes, frequency of heartburn, and interaction of pepsin with acid (see Chapter 43). In addition, studies in which acid reflux is monitored for more than 24 hours have demonstrated considerable daily variability in esophageal acid exposure.65,66 As noted, heartburn strongly suggests gastroesophageal acid reflux, but peptic ulcer disease, delayed gastric emptying, and even gallbladder disease can produce symptoms similar to those caused by reflux. Regurgitation is not quite as specific for acid reflux as heartburn, and the differential diagnosis of regurgitation should include an esophageal obstruction (e.g., ring, stricture, or achalasia) or a gastric emptying problem (e.g., gastroparesis or gastric outlet obstruction). Some patients have overlap among symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, dyspepsia, and irritable bowel syndrome (see Chapters 13, 43, and 118).67

The approach to patients with heartburn and regurgitation is discussed extensively in Chapter 43. In brief, published guidelines support an initial trial of acid suppressive therapy, generally with a proton pump inhibitor, as a diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver.68 This concept is cost-effective but plagued by limitations in sensitivity and specificity.69 If the cause of symptoms remains uncertain after a therapeutic trial, ambulatory intraesophageal pH testing is the best test to document pathologic esophageal acid exposure. Endoscopy of the esophagus is reserved for patients with symptoms suggestive of a complication (e.g., dysphagia, weight loss, signs of bleeding), but the predictive value of using a symptom profile to predict esophageal damage is questionable at best. Although not without controversy, most guidelines also suggest endoscopy to screen for Barrett’s esophagus in patients with chronic reflux symptoms70; the risk is particularly increased in older and obese patients.71,72

EXTRAESOPHAGEAL SYMPTOMS OF GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Extraesophageal symptoms of GERD are listed in Table 12-4. Although these symptoms may be caused by esophageal motility disorders, they are most frequently associated with GERD. In patients with extraesophageal symptoms, the classic reflux symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation often are mild or absent (see Chapter 43).

Table 12-4 Extraesophageal Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal reflux is thought to cause chronic cough and other extraesophageal symptoms as a result of recurrent microaspiration of gastric contents, a vagally mediated neural reflex or, in many patients, a combination of both. Although bronchodilators lower LES pressure, most persons with asthma have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. In animal studies, the instillation of small amounts of acid in the trachea or on the vocal cords73 can produce marked changes in airway resistance, as well as vocal cord ulcers. Direct evidence for aspiration is more difficult to identify in adults and rests primarily on the presence of fat-filled macrophages in sputum,74 radioactivity in the lungs after a tracer is placed in the stomach overnight,75 and a high degree of esophageal or hypopharyngeal acid reflux recorded by 24-hour pH monitoring with dual probes.76 Data from animal and human studies suggest that a neural reflex is another pathophysiologic basis for these symptoms. Acid perfusion into the distal esophagus increases airway resistance in all subjects, but the changes are most marked in patients with both asthma and heartburn.77

Abnormal amounts of acid reflux recorded by prolonged intraesophageal pH monitoring have been identified in 35% to 80% of asthmatic adults.78 Symptoms that suggest reflux-induced asthma include the onset of wheezing in adulthood in the absence of a history of allergies or asthma, nocturnal cough or wheezing, asthma that is worsened after meals, by exercise, or in the supine position, and asthma that is exacerbated by bronchodilators or that is glucocorticoid-dependent. In patients with reflux, symptoms strongly suggestive of aspiration include nocturnal cough and heartburn, recurrent pneumonia, unexplained fevers, and an associated esophageal motility disorder. Ear, nose, and throat complaints associated with gastroesophageal reflux include postnasal drip, voice changes, hoarseness, sore throat, persistent cough, otalgia, halitosis, dental erosion, and excessive salivation. Many patients with GERD complain of only head and neck symptoms. Examination of the vocal cords may help in evaluating patients with suspected acid reflux–related extraesophageal problems. Some patients have redness, hyperemia, and edema of the vocal cords and arytenoids. In more severe cases, vocal cord ulcers, granulomas, and even laryngeal cancer, all secondary to GERD, have been reported. Normal results of a laryngeal examination, however, are not incompatible with acid reflux–related extraesophageal symptoms, nor are the aforementioned laryngeal signs specific for a GERD-related pathogenesis.

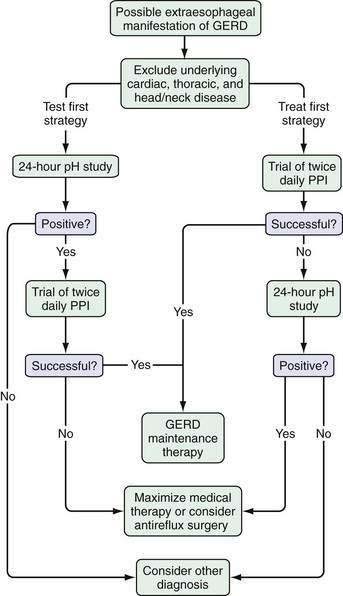

The options in a patient with suspected extraesophageal GERD are to study them with an ambulatory intraesophageal pH test or to initiate a trial of therapy to confirm the diagnosis and treat the symptom (Fig. 12-2). Either approach is reasonable, but many experts favor an initial trial of acid suppressive therapy with a proton pump inhibitor twice daily.79 Ambulatory pH testing is then reserved for those who fail the initial trial, although it is not clear whether pH testing should be done with the patient continuing or discontinuing acid-suppressive therapy (see Chapter 43).

The association between reflux and extraesophageal symptoms, particularly laryngeal symptoms, has been challenged. In one study, pH monitoring of the hypopharynx and proximal and distal esophagus was performed in patients with presumed acid reflux–related endoscopic laryngeal findings.80 An abnormal result was noted in only 15% of hypopharyngeal probes, 9% of proximal esophageal probes, and 29% of distal esophageal probes, thereby indicating that most patients (70%) with symptoms and signs of laryngeal reflux do not have documentable abnormal acid exposure. That preliminary study was followed by a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of esomeprazole, 40 mg twice daily, in the same patients, with response rates of 42% in those treated with esomeprazole and 46% in those treated with placebo.81 In addition, a randomized controlled trial of therapy with a proton pump inhibitor in asthmatics produced similar results.82 Despite the contradictory data, an early trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with symptoms suggestive of extraesophageal GERD is reasonable; however, the patient and physician should not be surprised if this therapy fails.

Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. There are no reliable symptoms for erosive oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus: Endoscopic diagnosis is still essential. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:735-42. (Ref 48.)

Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, et al. Abdominal obesity and body mass index as risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:34-41. (Ref 72.)

DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200. (Ref 68.)

Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, et al. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:45-52. (Ref 58.)

Fass R, Naliboff BD, Fass SS, et al. The effect of auditory stress on perception of intraesophageal acid in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;13:696-705. (Ref 55.)

Furuta G, Liacouras C, Collins M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: A systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63. (Ref 8.)

Henrikson CA, Howell EE, Bush DE, et al. Chest pain relief by nitroglycerin does not predict active coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:979-86. (Ref 26.)

Johnson DA, Fennerty MD. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660-4. (Ref 3.)

Kiljander TO, Harding SM, Field SK, et al. Effects of esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily on asthma: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Resp and Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1091-7. (Ref 82.)

Numans ME, Lau J, de Witt NJ, Bonis PA. Short-term treatment with proton-pump inhibitors as a test for gastroesophageal reflux disease. A meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:518-27. (Ref 69.)

Pandolfino JE, Richter JE, Ours T, et al. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring using a wireless system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:740-9. (Ref 66.)

Prakash C, Clouse R. Wireless pH monitoring in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:446-52. (Ref 45.)

Rey E, Moreno-Elola-Olaso C, Artalejo FR, et al. Association between weight gain and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in the general population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:229-33. (Ref 51.)

Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:254-60. (Ref 81.)

1. Bloem BR, Lagaay AM, van Beek W, et al. Prevalence of subjective dysphagia in community residents aged over 87. BMJ. 1990;300:721-2.

2. Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SC, et al. Prevalence of clinical spectrum of esophageal reflux: A population study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-56.

3. Johnson DA, Fennerty MD. Heartburn severity underestimates erosive esophagitis severity in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:660-4.

4. Triadafilopoulos G. Nonobstructive dysphagia in reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:614-18.

5. Clouse RE, McCord GS, Lustman PJ, Edmundowicz SA. Clinical correlates of abnormal sensitivity to intraesophageal balloon distention. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1040-5.

6. Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Psychiatric illness and contraction abnormalities of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1337-42.

7. Schatzki R, Gary JE. Dysphagia due to a diaphragm-like localized narrowing in the lower esophagus. AJR. 1953;70:911-22.

8. Furuta G, Liacouras C, Collins M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: A systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

9. Colon VJ, Young MA, Ramirez FX. The short and long-term efficacy of empirical esophageal dilation in patients with nonobstructive dysphagia: A prospective, randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:910-13.

10. Scolapio JS, Goustout CJ, Schroeder KW, et al. Dysphagia without endoscopically evident disease: To dilate or not? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:327-30.

11. Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Heartburn and globus in apparently healthy people. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;126:46-8.

12. Cook IJ, Dent J, Collins SM. Upper esophageal sphincter tone and reactivity to stress in patients with a history of globus sensation. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:672-6.

13. Ossakow SJ, Elta G, Coltura T. Esophageal reflux and dysmotility as the basis for persistent cervical symptoms. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96:387-92.

14. Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Mitchell L, Marshall T. Covert psychiatric disturbances in patients with globus pharyngitis. Br J Med Psychol. 1989;62:381-9.

15. Othmer E, DeSouza C. A screening test for somatization disorder (hysteria). Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1146-9.

16. Bishop LC, Riley WT. The psychiatric management of the globus syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;9:214-19.

17. Harar RP, Kumar S, Saeed MA, Gatland GJ. Management of globus pharyngeus: Review of 699 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:522-7.

18. Anandasabapathy S, Jaffin BW. Multichannel intraluminal impedance in the evaluation of patients with persistent globus on proton pump inhibitor therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:563-70.

19. Shay SS, Myers RL, Johnson LF. Hiccups associated with reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:204-7.

20. Kolodzik PW, Eilers MA. Hiccups (singultus): Review and approach to management. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:565-73.

21. Jiang F, Liu S, Pan J. Auricular needle-embedding therapy for treatment of stubborn hiccup. J Tradit Chin Med. 2003;23:123-4.

22. Richter JE, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Esophageal chest pain: Current controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:66-78.

23. Hewson EG, Sinclair JW, Dalton CB, Richter JE. Twenty-four hour esophageal pH monitoring: The most useful test for evaluating noncardiac chest pain. Am J Med. 1991;90:576-83.

24. Clark CS, Kraus BB, Sinclair J, Castell DO. Gastroesophageal reflux induced by exercise in healthy volunteers. JAMA. 1989;261:3599-601.

25. Davies HA, Jones DB, Rhodes J, Newcombe RG. Angina-like esophageal pain: Differentiation from cardiac pain by history. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:477-81.

26. Henrikson CA, Howell EE, Bush DE, et al. Chest pain relief by nitroglycerin does not predict active coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:979-86.

27. Siegel CI, Hendrix TR. Esophageal motor abnormalities induced by acid perfusion in patients with heartburn. J Clin Invest. 1963;42:686-95.

28. Richter JE, Johns DN, Wu WC, Castell DO. Are esophageal motility abnormalities produced during the intraesophageal acid perfusion test? JAMA. 1985;253:1914-17.

29. Peters L, Maas L, Petty D, et al. Spontaneous non-cardiac chest pain: Evaluation by 24-hour ambulatory esophageal motility and pH monitoring. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:878-86.

30. Janssens J, Vantrappen G, Ghillebert G. 24-hour recording of esophageal pressure and pH in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:1978-84.

31. Katz PO, Dalton CB, Richter JE. Esophageal testing in patients with non-cardiac chest pain and/or dysphagia. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:593-7.

32. Balaban DH, Yamamoto Y, Liu J, et al. Sustained esophageal contraction: A marker of esophageal cheat pain identified by intruminal ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:29-37.

33. MacKenzie J, Belch J, Land D, et al. Oesophageal ischemia in motility disorders associated with chest pain. Lancet. 1988;2:592-5.

34. Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of non-cardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:21-8.

35. Meyer GW, Castell DO. Human esophageal response during chest pain induced by swallowing cold liquids. JAMA. 1981;246:2057-9.

36. Kahrilas PJ, Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ. Dysfunction of the belch reflex. A cause of incapacitating chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:818-22.

37. Richter JE, Barish CF, Castell DO. Abnormal sensory perception in patients with esophageal chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:845-52.

38. Bass C, Cawley R, Wade C, et al. Unexplained breathlessness and psychiatric morbidity in patients with normal and abnormal coronary arteries. Lancet. 1983;1:605-9.

39. Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Eckert TC, et al. Low-dose trazodone for symptomatic patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities: A double-blind placebo controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1027-36.

40. Cannon RO, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiogram. N Engl J Med. 1994;19:1411-17.

41. Ali O, Smart FW, Nguyen T, Venterua H. Recent developments in microvascular angina. Curr Atherosclerosis Reports. 2001;3:149-55.

42. Singh S, Richter JE, Bradley LA, Haile JM. The symptom index: Differential usefulness in suspected acid-related complaints of heartburn and chest pain. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1402-8.

43. Achem SR, Kolts BE, MacMath T, et al. Effects of omeprazole versus placebo in treatment of noncardiac chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2138-45.

44. Fass R, Fennerty MB, Ofman JJ, et al. The clinical and economic value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:42-9.

45. Prakash C, Clouse R. Wireless pH monitoring in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:446-52.

46. Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SC, et al. Prevalence of clinical spectrum of esophageal reflux: A population study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-56.

47. Talley NJ, Wiklund I. Patient reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease: An overview of available measures. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:21-33.

48. Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. There are no reliable symptoms for erosive oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus: Endoscopic diagnosis is still essential. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:735-42.

49. Feldman M, Barnett C. Relationship between acidity and osmolality of popular beverages and reported postprandial heartburn. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:125-31.

50. Katz LC, Just R, Castell DO. Body position affects postprandial reflux. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;18:280-3.

51. Rey E, Moreno-Elola-Olaso C, Artalejo FR, et al. Association between weight gain and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in the general population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:229-33.

52. Clark CS, Kraus BB, Sinclair J, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux induced by exercise in healthy volunteers. JAMA. 1989;261:3599-601.

53. Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RP. Mechanisms of acid reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut. 1990;31:4-10.

54. Bradley LA, Richter JE, Pulliam TJ, et al. The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux: The influence of psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:11-19.

55. Fass R, Naliboff BD, Fass SS, et al. The effect of auditory stress on perception of intraesophageal acid in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;13:696-705.

56. Helm JF, Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ. Salivary response to esophageal acid in normal subjects and patients with reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1393-7.

57. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:419-486.

58. Farup C, Kleinman L, Sloan S, et al. The impact of nocturnal symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:45-52.

59. Rodriguez-Stanley S, Robinson M, Earnest DL, et al. Esophageal hypersensitivity may be a major cause of heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:628-31.

60. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Role of acid and duodenogastro-esophageal reflux in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1192-9.

61. Marrero JM, de Caestecker JS, Maxwell JD. Effect of famotidine on oesophageal sensitivity in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1994;35:447-50.

62. Baldi F, Ferrarini F, Longanes A, et al. Acid gastroesophageal reflux and symptom recurrence. Analysis of some factors influencing their association. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1890-3.

63. Johnson DA, Winters C, Spurling TJ, et al. Esophageal acid sensitivity in Barrett’s esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:23-7.

64. Fass R, Pulliam G, Johnson C, et al. Symptom severity and oesophageal chemosensitivity to acid in older and young patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Age Ageing. 2000;29:125-30.

65. Booth MI, Stratford J, Dehn TCB. Patient self-assessment of test-day symptoms in 24-h pH-metry for suspected gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:795-9.

66. Pandolfino JE, Richter JE, Ours T, et al. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring using a wireless system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:740-9.

67. Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, et al. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2454-9.

68. DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200.

69. Numans ME, Lau J, de Witt NJ, Bonis PA. Short-term treatment with proton-pump inhibitors as a test for gastroesophageal reflux disease. A meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:518-27.

70. Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-97.

71. Collen MJ, Abdulian JD, Chen YK. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in the elderly: More severe disease that requires aggressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1053-7.

72. Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, et al. Abdominal obesity and body mass index as risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:34-41.

73. Little FB, Koufman JA, Kohut RI. Effect of gastric acid on the pathogenesis of subglottic stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94:516-19.

74. Crausaz FM, Favez G. Aspiration of solid food particles into lungs of patients with gastroesophageal reflux and chronic bronchial disease. Chest. 1988;93:376-8.

75. Chernow B, Johnson LF, Janowitz WR, et al. Pulmonary aspiration as a consequence of gastroesophageal reflux: A diagnostic approach. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:839-44.

76. Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, et al. Most asthmatics have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:613-20.

77. Mansfield LE, Stein MR. Gastroesophageal reflux and asthma: A possible reflex mechanism. Ann Allergy. 1978;41:224-6.

78. Harding SM, Richter JE. The role of gastroesophageal reflux in chronic cough and asthma. Chest. 1997;111:1389-402.

79. Wo JM, Frist WJ, Gussack G, et al. Empiric trial of high-dose omeprazole in patients with posterior laryngitis: A prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2160-5.

80. Richter J, Vaezi M, Stasney CR, et al. Baseline pH measurements for patients with suspected signs and symptoms of reflux laryngitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:A536.

81. Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:254-60.

82. Kiljander TO, Harding SM, Field SK, et al. Effects of esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily on asthma: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1091-7.