5 Suture Material

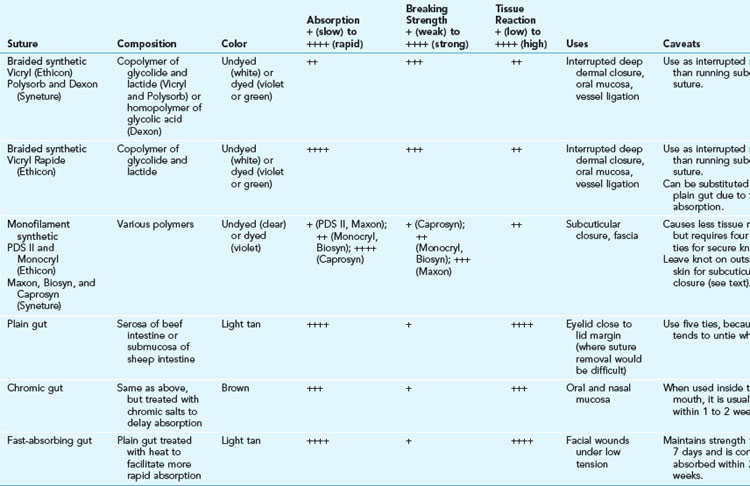

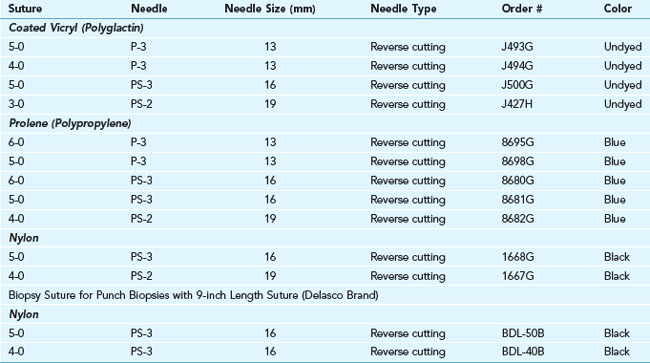

Many types of sutures are available, each with its own material properties, performance, and uses. The most useful sutures for skin surgery are described in detail in Tables 5-1 and 5-2.

History

The use of sutures to close wounds is certainly not limited to the modern era. Ancient civilizations developed innovative methods to close wounds based on the materials then available. Horsetail hair threaded onto eyed needles made from bone was utilized by the Greeks as early as 5000 to 3000 B.C. An Egyptian scroll dating back to 3000 B.C. describes the use of linen as suture material.1 South American Indians essentially created the first surgical “stapler” by using the heads of pincher ants to close wounds. The Roman physician Galen described the use of absorbable suture, specifically catgut, in 175 A.D.2 Sterile suture material was formally introduced by Lister in 1869 by treating catgut with chromic acid.3 Interestingly, the benefit of using sterile sutures was discovered during the American Civil War a few years earlier (1861–1865). Due to a lack of available suture material, Confederate surgeons were reduced to using horsetail hair, which they boiled to make more pliable. This inadvertent sterilization of the suture material most likely led to the lower wound infection rate they experienced as compared to their Union colleagues.4

Wound Healing and Sutures

Wound healing is described by tensile strength, the force per unit area required to pull a wound apart. Studies show that a wound does not begin to gain significant tensile strength until about 3 weeks after closure at which point it has only 10% of its final tensile strength. Tensile strength increases more quickly after 3 weeks and reaches its maximum strength at around 60 days. It never returns to more than 80% of normal skin.5 Thus, wounds subject to any tension should usually be closed in two layers: a deeper dermal layer with suture material that will maintain significant strength for 6 to 8 weeks, and a second superficial skin suture that can be removed in 7 days or less without fear of wound disruption. A suture or staple left in the skin for more than 10 days will often allow epithelial cells to grow from the surface down into the dermis along the suture or staple tract, resulting in permanent scar tissue on each side of the incision scar itself and detracting from the final appearance of the healed wound. In addition, a suture that is tied too tight will cause necrosis and subsequent scarring of the enclosed tissue within the loop, resulting in cross-hatch marks, or “railroad tracks.” The goal of the superficial suture layer is to carefully approximate the epidermis, not to add significant strength to the closure. The deeper dermal sutures should take nearly all tension off the epidermal closure.

Suture Material Properties

Suture material is judged by several characteristics:

Absorbability and Breaking Strength

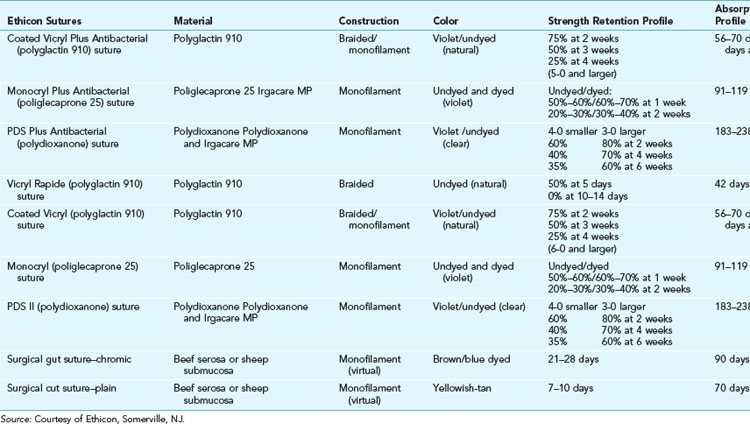

These terms are somewhat interrelated, as the absorbability of the suture correlates with the breaking strength of the suture with time. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) officially defines absorbable sutures as those that lose breaking strength within 60 days, whereas nonabsorbable sutures retain their breaking strength beyond 60 days. See Table 5-3 for the details of strength retention and absorption in absorbable sutures. Breaking strength relates to the material used for construction of the suture as well as its diameter. The USP also defines the diameter of sutures. Sutures used for the skin usually range from 3-0 (relatively thick) to 6-0 (relatively thin). The smallest suture now available is 11-0 (about one-third the diameter of a human hair) and is utilized for the microsurgical repair of small blood vessels.

Absorbable Sutures

The absorbable sutures available in the United States are described in Table 5-1. Ethicon, a division of Johnson & Johnson, and Syneture, a division of Covidien, control 99% of the U.S. market (Ethicon, ~80%; Syneture, ~20%).6 Although absorbable suture is defined by its loss of strength within 60 days, the suture is not completely gone at that time. Even quickly absorbing sutures such as catgut can be found in the tissues for up to two years.7

Surgical Gut

Gut sutures have been used since 175 A.D. In addition to sutures, gut was also used for violin strings and bowstrings and, more recently, tennis racket strings. Gut sutures, also referred to as catgut, are derived from the intimal layer of the small intestines of sheep or cattle, and have nothing to do with cats. The origin of the name is unknown, but is thought to be derived from the word kitgut (fiddle string) with kit being the name of an Arabian fiddle with strings made from sheep intestine.8 Due to its heterogeneic derivation, it is highly inflammatory and is broken down quickly in vivo. Plain gut retains significant strength for only 4 to 5 days. Gut can be treated with chromic salts to essentially double its resistance to absorption. It is useful for closing oral, nasal, or vaginal mucosa where significant strength is not required beyond a week. Plain gut can be used in areas where suture removal may be difficult, such as near the lash line of the eyelids, but should not be used if the wound is under any tension. When using plain gut, five knots are necessary because it has a tendency to untie spontaneously when wetted.

As early as 1894 concerns were raised that the use of gut suture could potentially transmit anthrax bacilli and spores or other infectious material in the sheep.8 In the 1990s, the use of gut diminished significantly in Europe due to concerns about possible transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (“mad-cow disease”), although there has never been a documented case of this occurring. Currently, the raw material is derived from herds certified free of the disease, and is highly processed. However, synthetic sutures are available that have comparable absorption profiles and handling characteristics and are less reactive, such as Vicryl Rapide™ (Ethicon) and Caprosyn™ (Syneture), that can be substituted for plain and chromic gut (see Table 5-1).

Synthetic Braided and Monofilament Sutures

The first of these was Dexon™ (Syneture), which became commercially available in 1971.2,9 It is a synthetic braided homopolymer of glycolic acid. In 1974 Vicryl™ (Ethicon) was introduced. Vicryl (polyglactin 910) is a synthetic braided copolymer of glycolide and L-lactide. These sutures are absorbed by gradual hydrolysis rather than by the host inflammatory response caused by gut. Their braided surfaces allow for easy handling and secure knots. However, the larger surface area and interstices of braided material can lead to entrapment of bacteria and possibly lead to a localized inflammation (“spitting” of the suture) (Figure 5-1) or more generalized wound infection.

Bioactive Sutures

In 2002, Ethicon released Coated Vicryl Plus™, an absorbable braided suture coated with triclosan, a broad-spectrum biocide used for more than 30 years in products such as toothpaste and soap. Its efficacy has been demonstrated in vivo and in animal models in which S. aureus is introduced into the wound during closure.10 Preliminary results suggest a reduction in sternal wound infections when used for closure of the sternal incision, and a reduction in shunt-infection rates when the suture is used for skin closure following the insertion of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunts.11,12 This is the first “bioactive” suture to serve the dual purpose of closing a defect as well as decreasing the wound infection rate.

Nonabsorbable Sutures

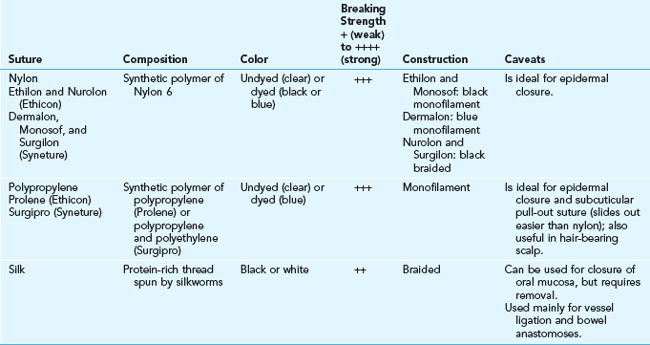

Nonabsorbable sutures are typically used to close the epidermal layer of skin due to their low tissue reactivity and superior strength compared to absorbable sutures. They are also used for closure of fascia as well as hernia or tendon repair because they lose very little tensile strength with time. See Table 5-2 for an overview of the nonabsorbable sutures and their relevant properties.

Needles

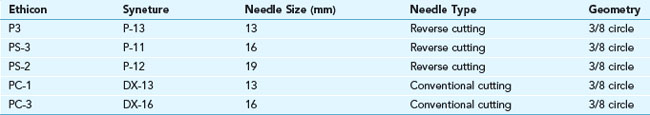

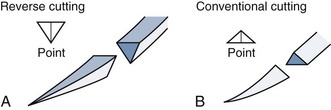

Needle points can be blunt, tapered, cutting, or spatulated. A cutting needle is preferred for skin surgery. Its cross section is triangular rather than round, and thus stronger and more resistant to bending. The conventional cutting needle has one pointed edge along the inside of the curve of the needle, and thus can potentially cut tissue along a wound edge. To avoid this problem, the reverse-cutting needle was created so that the third cutting edge is on the outside curve of the needle, away from the edge of the wound (Figure 5-2).

FIGURE 5-2 (A) Reverse-cutting needles. (B) Conventional cutting needles.

(Redrawn from and courtesy of Ethicon product catalog Sutures/Adhesives/Drains/Hernia Repair.)

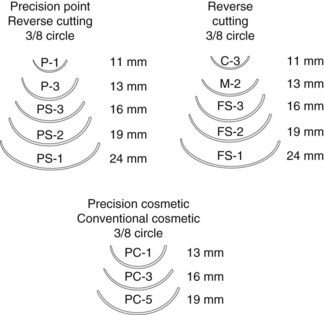

Needles from Ethicon used in skin surgery are named with the following nomenclature:

See Figure 5-3 for a comparison of the many types of three-eighths needles made by Ethicon that are used in skin surgery.

FIGURE 5-3 Needles for skin surgery.

(Adapted from Ethicon product catalog Sutures/Adhesives/Drains/Hernia Repair.)

Needles from Syneture used in skin surgery are named with the following nomenclature:

See Tables 5-4 and 5-5 for more details about needles and sutures. Personal preferences for needles develop through experience and help clinicians choose their preferred needle in each surgical situation.

Suture and Needle Selection

Suture Selection

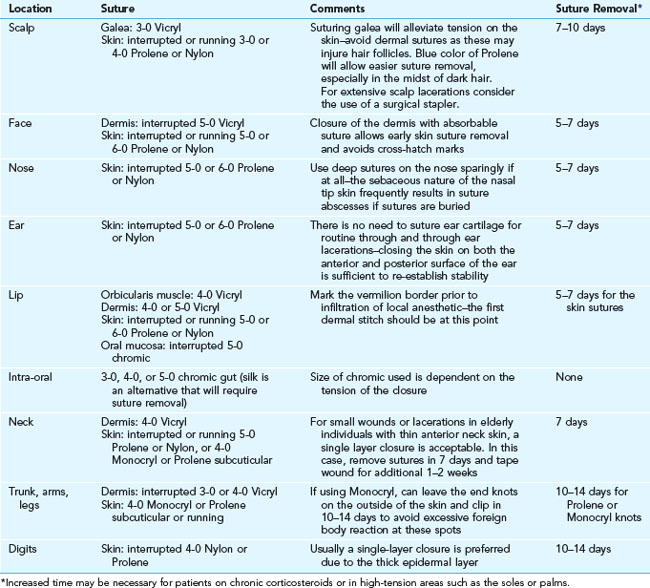

The ideal suture would hold tissues together until they have gained enough tensile strength to heal without the risk of dehiscence. After that time, the suture material would disappear, leaving no sign that it was ever there. Although no such suture currently exists, some sutures are more appropriate for certain circumstances than others. For tissues that heal slowly such as fascia and tendon, a nonabsorbable suture is preferred. For skin, a two-layered closure is preferred, with suture size varying depending on the area of the body. Extremity and trunk skin tends to be thicker and under more tension than facial skin, and therefore larger needles and sutures are preferred. Table 5-6 is a listing of preferred suture by location. The sutures listed are manufactured by Ethicon, as they currently provide 80% of sutures in the United States. We have no ties (pun intended) to Ethicon and have found both Ethicon and Syneture sutures to be equal in performance.

Conclusion

The large variety of sutures available makes it difficult to decide which products are going to be right for you and your patients. Table 5-5 contains detailed information about the commonly stocked skin sutures in an office practice. To do the procedures in this book, you will need at least one type of absorbable and one type of nonabsorbable suture. The minimum starting set should probably include:

Resources

1. Stroumtsos O. Perspectives on Sutures. Pearl River, NY: Davis and Geck; 1978.

2. Katz AR, Turner RJ. Evaluation of tensile and absorption properties of polyglycolic acid sutures. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1970;131:701-716.

3. Goldenberg I. Catgut, silk, and silver—the story of surgical sutures. Surgery. 1959;46:908-912.

4. McCallum JE. Military Medicine: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2008. 383–313

5. Levenson SM, Geever EF, Crowley LV, et al. The healing of rat skin wounds. Ann Surg. 1965;161:293-308.

6. Sluggish demand keeps suture pricing relatively flat. Hosp Mater Manage. 2009;34(1):6-8.

7. Bennett RG. Selection of wound closure materials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:619-637.

8. Booth AW. The preparation of surgical catgut. Therapeut Gazette. 1894;18:810-819.

9. Herrmann JB, Kelly RJ, Higgins GA. Polyglycolic acid sutures. Laboratory and clinical evaluation of a new absorbable suture material. Arch Surg. 1970;100:486-490.

10. Storch ML, Rothenburger SJ, Jacinto G. Experimental efficacy study of coated Vicryl plus antibacterial suture in guinea pigs challenged with Staphylococcus aureus. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2004;5:281-288.

11. Fleck T, Moidl R, Blacky A, et al. Triclosan-coated sutures for the reduction of sternal wound infections: economic considerations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:232-236.

12. Rozzelle CJ, Leonardo J, Li V. Antimicrobial suture wound closure for cerebrospinal fluid shunt surgery: a prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2:111-117.