Chapter 20 Surgical Techniques for Nerve Tumors

Benign Tumors

Incision

• The surgical approach is tailored according to the nerve and the level involved, but the major principles are similar. When possible, the nerve leading into and out of the tumor should be exposed.

• This usually requires a longitudinal incision on the limb, neck, or shoulder and not a short or transverse incision.

• Excellent exposure of structures adjacent to and both proximal and distal to the lesion is paramount. Adjacent nerves, vessels, or other adherent structures must also be dissected away and protected.

Dissection of Fascicles Around the Tumor

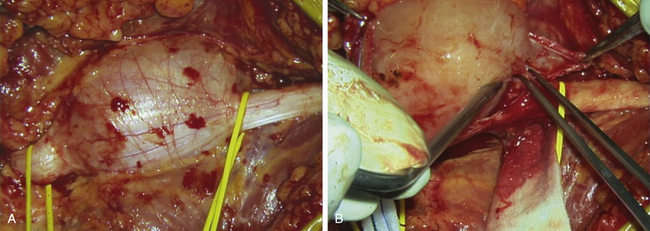

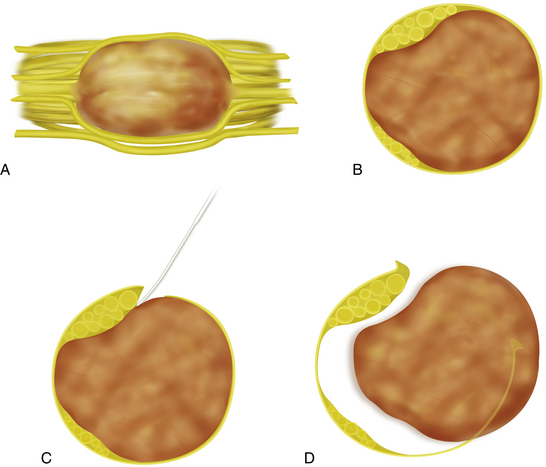

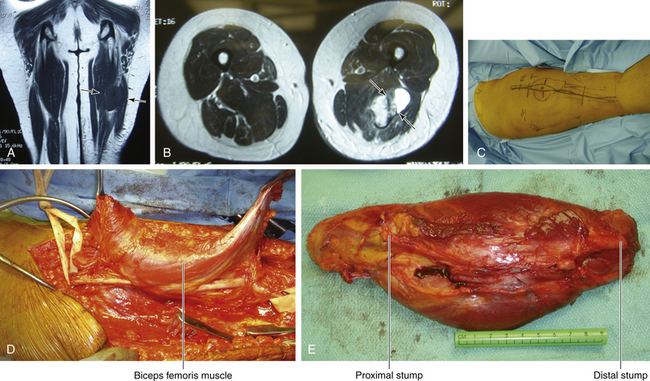

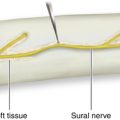

• The majority of these lesions, whether schwannoma or neurofibroma, are intraneural in locus. The tumor has usually displaced, thinned out, and “basketed” the fascicles so that they encircle the lesion (Figure 20-1). Sometimes the neural sheath tumor has grown in an eccentric fashion, displacing most fascicles to one side of the mass (Figure 20-2).

• It is usual to begin by making a longitudinal incision between the fascicles that are spanned or basketed around the tumor.

• The best spot for this is usually on the circumference of the tumor, where the fascicles are not so closely compacted.

• The pseudocapsule, if present, is opened, and this and the fascicles are gradually worked away from the tumor itself (Figure 20-3).

• This intraneural dissection can be done with a variety of tools. The perineurium of fascicles is preserved. Accuracy is essential and is most easily achieved by microsurgical technique with magnification. The patient should not incur any additional neurological deficit unless the case is especially complex.

• Fascicles are gradually moved to either side and away from the tumor mass.

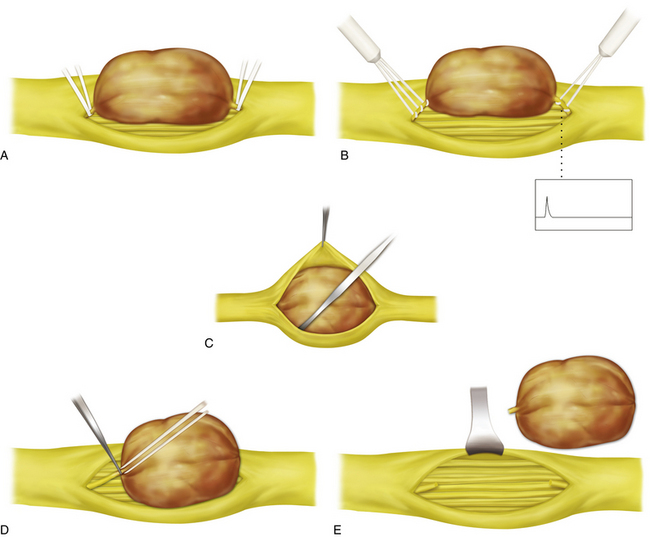

• Because there is usually fascicular input and output to the tumor itself, an interfascicular dissection of the nerve is done at both the proximal and distal poles of the tumor.

• In this way, most fascicles can be traced into the base and sides of the capsule, and the specific fascicles that enter and leave the neoplasm can be identified (Figure 20-4).

• If the tumor is a schwannoma, the intraneural fascicle is usually a single, fairly small fascicle at either end entering and leaving the core of the tumor.

• Nerve stimulation of such a fascicle usually gives a negative response. This means that the entering and leaving fascicle can be sectioned without functional loss.

• This fascicle is usually isolated by a plastic loop, evaluated, and then sectioned proximal and distal to the tumor. The tumor is then removed as a solitary mass.

• If the entering and leaving fascicles are examined histologically, one sees a rudimentary array of immature, poorly developed axons. These fibers are small and poorly myelinated, and the surrounding structure is disorganized.

• In the case of neurofibromas, there may be more than one fascicle entering and leaving the substance of the tumor; if there is a single fascicle, it is usually larger than those seen in schwannomas.

• It is very important to work out the fascicular anatomy at both the proximal and distal poles of such lesions.

• What appear to be fascicles intrinsic to the neurofibroma are often shown to be external to the bulk of the tumor when the polar anatomy is displayed.

• The entering or leaving fascicles are sectioned and used as a handle. The tumor is then elevated out of and away from its fascicular structure until the opposite pole is reached; the residual entering or leaving fascicles are then sectioned, and the tumor is totally removed.

• The distinction between a solitary schwannoma and a neurofibroma may be obvious at surgery, or the distinction may only be apparent at pathological examination of the specimen.

• The risk of causing neurological loss by careful excision of a schwannoma is very small, but that statement does not apply to neurofibroma cases. Functioning fascicles may be intrinsically enmeshed within the tumor, so that stimulation and, if necessary, NAP studies must be conducted with care. Significant clinical judgment is required in making the decision to cut functioning fascicles, which may be needed to totally excise a tumor.

• The informed consent and good clinical judgment may lead the surgeon to a subtotal excision or to retreat after a biopsy without any definitive surgery. These cases are followed with intermittent clinical examination and scans.

• Neither overly timid nor overly aggressive surgery serves the patient well. A skilled, experienced microsurgeon will be able to weigh the risks and excise a focal neurofibroma with relative safety. Such a surgeon knows when to quit when local conditions indicate that the stakes are becoming too high.

• There are no small or easy operations. Surgeons embarking on a simple schwannoma excision may occasionally find that they are confronted with a difficult neurofibroma. Mismanaging such a case will have unfortunate consequences for the patient and possible unfortunate medicolegal consequences for the surgeon.

Specimen Handling

• For lesions that appear benign—that is, those that are not hard, not fixed to adjacent structures, and whose fascicular structure is preserved—a biopsy or specimen for frozen section is usually not sent, although that certainly can be done.

• Instead, the whole specimen is usually submitted for more permanent processing and diagnosis.

• The operating room staff must be fully informed of the requirements of the pathologist with regard to specimen handling for future light or electron microscopic or molecular studies.

Special Circumstances

• Lesions close to the spine may require special exposure, such as a posterior subscapular approach for a spinal nerve lesion in the brachial plexus.

• Large tumors may require a more piecemeal excision. In such cases, it is important to identify and protect less-involved elements or nerves, as well as vessels. Use of the Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA) may be necessary.

• When there has been a prior attempt at removal or open surgical biopsy, it may help to dissect out the entire nerve with its enclosed tumor and then turn it over and work on the previously unexposed side.

Malignant Tumors

Establishing the Diagnosis

A rapid clinical progression of a nerve mass should arouse suspicion, but such clues may be absent.

• A neurogenic sarcoma or malignant schwannoma can be strongly suspected if one finds a firm to hard lesion with progressive pain and loss of function or a lesion during surgery that is adherent to adjacent structures and difficult to dissect out.

• Sometimes the lesion may be diagnosed from preoperative needle biopsies taken from multiple loci.

• It is essential that specimens be reviewed by a pathologist with skill in this area. Many experienced pathologists have little exposure to this field. The distinction between benign and malignant cases may be clear cut, but this is not always the case. We do not move to major compartment surgery or, in rare cases, amputation based on frozen section results unless a truly experienced pathologist states that there are florid changes of malignancy.

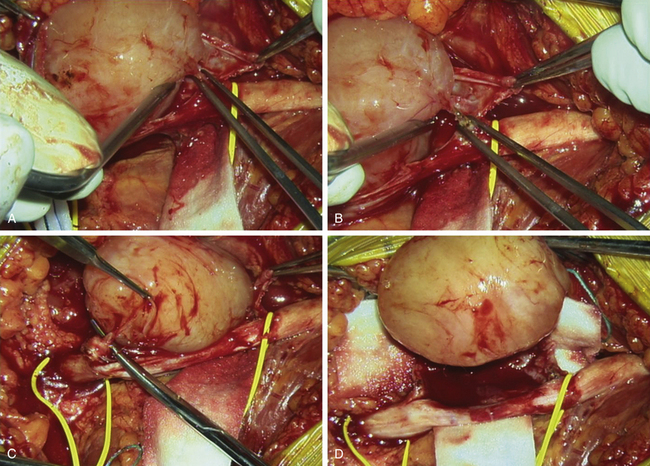

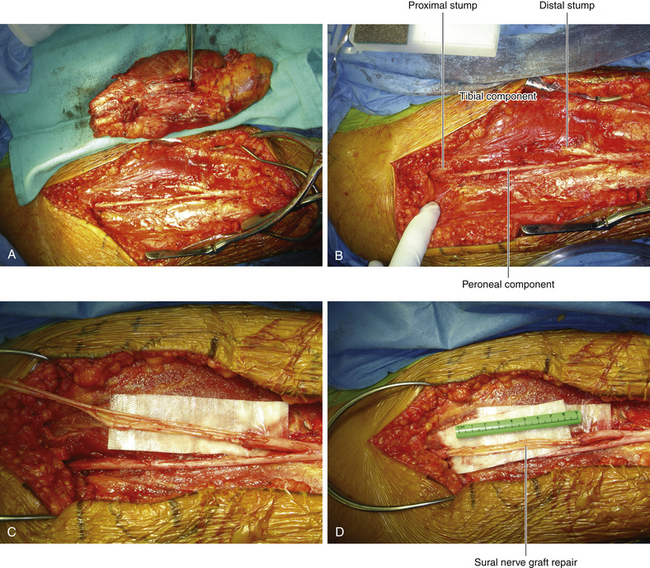

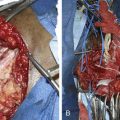

• Careful planning of a wide local resection with removal of the nerve of origin and adjacent scar tissue is necessary, as is appropriate conditioning of the patient and obtaining truly informed consent (Figures 20-5 and 20-6).

• Sections of the nerve of origin proximal and distal to the tumor must be inspected carefully, both visually and histologically, looking for residual tumor. A characteristic of these tumors is intraneural spread; therefore sections from either extremity of the nerve specimen should be examined with care to be certain that they are histologically clear.

• Malignancy in cases of neurofibromatosis may challenge the skills and experience of any pathologist who does not have a special interest in this field.

• Surgery, whether wide local resection, forequarter amputation, or hip- or pelvic-level disarticulation, is dependent on permanent tissue histological findings and the wishes of the patient and family.

• In recent years, we have favored limb-sparing surgery whenever possible for sarcomas involving the extremities, but sometimes amputation or forequarter amputation has still been done.

Other Types of Tumors Involving Nerves

• Other types of tumors involving nerves are almost legion in number. Surgical approaches are somewhat different and vary for lipomas, ganglioneuromas, ganglionic cysts, epidermoids, osteochondromas, hemangiomas, hemangioblastomas, and meningiomas.

• For example, resection of a desmoid tumor involving a nerve or plexus, although possible, may be associated with further or new deficits. Such tumors are very adherent to the nerve, very difficult to extricate—especially when involving the plexus—and very likely to recur.

• Fibrous osteitis is sometimes associated with prior and usually severe soft tissue injury near a nerve or may occur in patients who are chronically ill, especially those with renal failure and needing dialysis.

• The process leads to a usually hard and partially calcified mass that may involve both nerves and vessels. Good exposure that permits dissection from both the proximal and distal ends of such masses, as well as laterally, medially, and posteriorly, is paramount.

Lumbar Sympathectomy

Patient Positioning

• The patient is anesthetized in a supine position using an endotracheal technique.

• A rolled sheet or several folded sheets are placed under the flank on the side to be operated.

• The hip and knee are partially flexed by placing a pillow beneath the ipsilateral knee. This tends to relax the psoas muscles somewhat.

Incision

• A skin incision is made in the flank obliquely from the tip of the lower ribs toward the inguinal region. The incision is usually 10 to 12 cm in length.

• A 12-inch skin incision is made from the tip of the lowest rib, in a downward and anterior direction.

• The abdominal wall muscles are split in the direction of their fibers.

• The surgeon’s fingertips establish a plane hard up against the posterior abdominal wall, in the extraperitoneal space. The fingertips progress medially untill the psoas major is encountered.

• Appropriate retractors are inserted, holding the peritoneum and its contents forward, so that the sympathetic chain can be seen from the level of the diaphragm to the sacral promontory.

• The approach should be meticulously accurate, with immediate control of any small bleeding vessels. Excellent illumination and retraction is required. The surgeon must previously have studied the position of the chain and its relationship to the great vessels and psoas so that the site at which the chain is identified is clearly in the surgeon’s mind. Failure to observe these simple steps causes the conversion of a straight forward procedure into a situation characterized by doubt in identifying the chain, unnecessary biopsy of tissue in the hope of finding ganglia, and inadequate reaction of the sympathetic chain. In this latter circumstance the failure of surgery is immediately obvious on examining the leg, once the surgical drapes are removed at the end of the procedure.

• This retractor is also used to help expose the lateral portion of the lumbar vertebrae. Another curved abdominal retractor can be inserted more cephalad, at or above the attachments of the crus of the diaphragm.

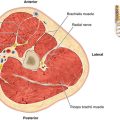

The Lumbar Sympathetic Chain

• The lumbar sympathetic chain is usually found lying in the gutter formed by the rounded portion of the bodies of the vertebrae and the more medial portion of the belly of the psoas.

• The sympathetic chain can be elevated with a long-handled nerve hook so that the rami, and then both ends of the chain close to the diaphragmatic crus and at the lumbosacral promontory, can be sectioned.

• The chain may lie beneath lumbar arterial branches on the left side or lumbar bridging veins on the right side, and these may need to be tied off or coagulated before the chain is dissected out.

• In addition, on the right side, some of the vena cava may lie over the sympathetic chain, requiring gentle elevation of that vessel to expose the chain more completely.