Chapter 55 Surgical Perspectives on Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES)

Introduction

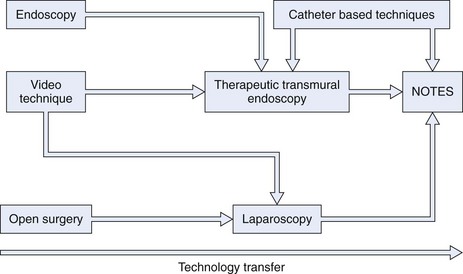

Surgical procedures have been performed since Neolithic times with advances in the field marked by key events.1 In 1809, McDowell completed the first successful abdominal operation without the use of general anesthetic.2 The invention and use of inhaled ether as a form of general anesthetic marks the first great advance in surgical therapy (Fig. 55.1), followed by the introduction of antisepsis by Lister.3 In the centuries that followed, large abdominal incisions were required to permit the surgeon’s hands and instruments access to the disease process. More recently, disease processes have been accessed with smaller incisions (as in laparoscopy) or by a different route entirely (endoscopy or endovascular), decreasing the pain and infection risk of the abdominal incision and improving patient outcomes.

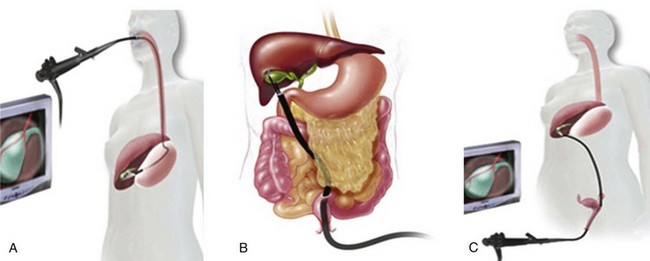

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) is an experimental surgical technique whereby scarless abdominal operations can be performed with an endoscope passed through a natural orifice (mouth, anus, vagina, or urethra) and then through an internal incision in the stomach, colon, posterior vaginal fornix, or bladder, avoiding any external incisions or scars (Fig. 55.2). Similar to the introduction of laparoscopy, surgical opinions of this new approach vary widely. This chapter briefly reviews NOTES and examines current surgical opinions.

History of Minimally Invasive Surgery

The advent of minimally invasive surgery brought with it an opportunity to decrease postoperative pain with resultant shorter hospital stays and quicker returns to normal activity and to shrink surgical scars, providing a more pleasing cosmetic outcome.4 The minimally invasive surgery concept influenced the next paradigm shift in intervention, NOTES, which may eliminate the anterior abdominal wall approach altogether (Fig. 55.3).

History of Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery

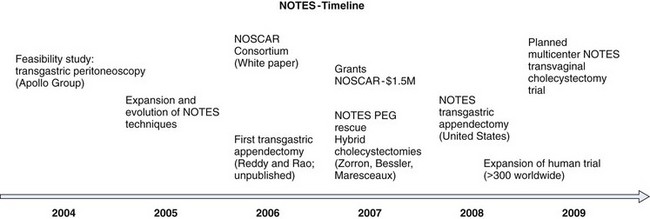

The history of NOTES begins in 1901, when Ott performed the first endoscopic examination of the peritoneal cavity through the vagina.5 He termed the procedure ventroscopy and became the pioneer of natural orifice access. The feasibility of a peroral transgastric flexible endoscopic approach to the peritoneal cavity with long-term survival in a porcine model was reported by the Apollo Group in 2004 (Fig. 55.4).4 Since this publication, NOTES has continued to evolve. Success in early animal studies led to the initiation of human trials.6–11 Rao and Reddy performed the first flexible endoscopic transgastric appendectomy in humans in Hyderabad, India; although this report remains unpublished, a description of their technique and videos have become widely dispersed throughout the research community.12,13 Since that time, this group has successfully attempted the transluminal approach for 17 cases, including appendectomy, liver biopsy, and tubal ligation.14 Multiple transvaginal and transgastric NOTES procedures have been published by other NOTES teams, including transgastric appendectomy, cholecystectomy, fallopian tube ligation, and transvaginal cholecystectomy with active clinical trials ongoing.15–20 Currently, the number of successful NOTES procedures (with or without laparoscopic assistance) around the world is greater than 3000 cases.

Advantages of Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery

Abdominal incisions elicit a pain reaction that results in a stress response from the body, initiated through the inflammatory cytokine cascade. Theoretical advantages of NOTES include the avoidance of this pain reaction and stress response. A possible development can be imagined with procedures under conscious sedation rather than general anesthesia. This development has already occurred for several procedures that used to be the domain of open surgery, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis or pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. As is shown with the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy rescue report by Marks and colleagues,21 transluminal procedures may avoid additional insults to ill patients. In addition to the esthetic improvements offered by incisionless surgery, NOTES would also decrease the risk of wound infection and postoperative incisional hernias. NOTES may be ideally suited for patients who have conditions that preclude an open or laparoscopic procedure, such as patients with large areas of burn, scar, or infection of the anterior abdominal wall. Additionally, the NOTES team and equipment are portable allowing procedures to be done in an intensive care unit, multipurpose procedure room, outpatient setting, and battlefield.

Training Surgeons in Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery and Incorporating Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery into a Surgical Practice

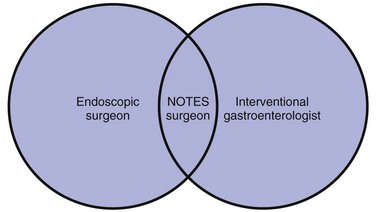

As with any new technique, training is important for the clinical incorporation of NOTES. Because of the unique equipment used and the operative view obtained in NOTES procedures, a NOTES surgeon requires specialty training similar to other surgical fellowships and specialties. Although no formal programs have been designed, it is likely that a NOTES surgeon would require an education in general surgery concepts and advanced endoscopic training (Fig. 55.5). Several procedures in the vascular environment are now performed by either vascular surgeons or radiologists and training for both types of specialists has evolved to combine more of both specialties. A similar training model could be applied for training of NOTES surgeons.

1 Clower WT, Finger S. Discovering trepanation: The contribution of Paul Broca. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1417-1425.

2 Tan S, Wong C. Ephraim McDowell (1711–1830): Pioneer of ovariotomy. Singapore Med J. 2005;46:4-5.

3 Lister J. On the antiseptic principle of the practice of surgery. In: Eliot C, editor. The Harvard classics, Vol. 38. New York City: Collier & Son; 2001.

4 Kalloo A, Singh V, Jagannath S, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: A novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:114-117.

5 Harrell A, Heniford B. Minimally invasive abdominal surgery: Lux et veritas past, present, and future. Am J Surg. 2005;190:239-243.

6 Jagannath S, Kantsevoy S, Vaughn C, et al. Peroral transgastric endoscopic ligation of fallopian tubes with long-term survival in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:449-453.

7 Kantsevoy S, Hu B, Jagannath S, et al. Transgastric endoscopic splenectomy: Is it possible? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:522-525.

8 Kantsevoy S, Jagannath S, Niiyama H, et al. Endoscopic gastrojejunostomy with survival in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:287-292.

9 Park P, Bergstrom M, Ikeda K, et al. Experimental studies of transgastric gallbladder surgery: Cholecystectomy and cholecystogastric anastomosis (videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:601-606.

10 Wagh M, Merrifield B, Thompson C. Endoscopic transgastric abdominal exploration and organ resection: Initial experience in a porcine model. Clin Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;3:892-896.

11 Wagh M, Merrifield B, Thompson C. Survival studies after endoscopic transgastric oophorectomy and tubectomy in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:473-478.

12 Hochberger J, Lamade W. Transgastric surgery in the abdomen: The dawn of a new era? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:293-296.

13 Ponsky J. Gastroenterologists as surgeons: What they need to know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:454.

14 Rao G, Reddy D, Banerjee R. NOTES: Human experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;18:362-370.

15 Bessler M, Stevens P, Milone L, et al. Transvaginal laparoscopically assisted endoscopic cholecystectomy: A hybrid approach to natural orifice surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1243-1245.

16 Hazey J, Narula V, Renton D, et al. Natural-orifice transgastric endoscopic peritoneoscopy in humans: Initial clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:16-20.

17 Marescaux J, Dallemagne B, Perretta S, et al. Surgery without scars: Report of transluminal cholecystectomy in a human being. Arch Surg. 2007;142:823-826.

18 Palanivelu C, Rajan P, Rangarajan M, et al. Transvaginal endoscopic appendectomy in humans: A unique approach to NOTES—world’s first report. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1343-1347.

19 Zornig C, Mofid H, Siemssen L, et al. Transvaginal NOTES hybrid cholecystectomy: Feasibility results in 68 cases with mid-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2009;41:391-394.

20 Zorron R, Filgueiras M, Maggioni L, et al. NOTES. Transvaginal cholecystectomy: Report of the first case. Surg Innov. 2007;14:279-283.

21 Marks J, Ponsky J, Pearl J, et al. PEG “Rescue”: A practical NOTES technique. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:816-819.