6 Surgical oncology

Aetiology

The causes of malignancy are multifactorial. No single chemical or biological factor has been shown to cause cancer but a combination of factors, for example genetic susceptibility, chemicals, occupation, lifestyle and viruses, may induce malignant change in certain tissues in susceptible individuals (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Examples of causative factors in malignant disease

| Causative factor | Tumour | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | ||

Invasion and metastasis

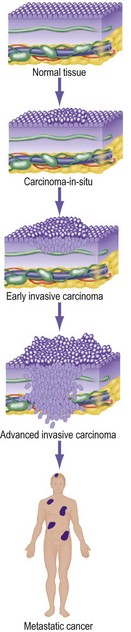

The difference between a benign and a malignant tumour is the capacity to invade and metastasise. A benign tumour generally grows slowly, is always well encapsulated and may compress, but never invades, local tissues. In contrast, cancers invade surrounding tissues (Fig. 6.1) and spread to form distant tumour deposits (metastases).

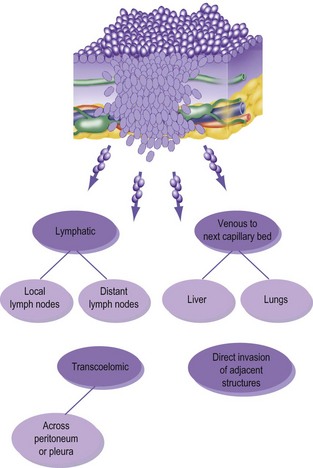

Metastases occur by three routes (Fig. 6.2):

• lymphatic spread to local and distant nodes

• haematogenous spread (mainly to lung, liver and bone)

• transcoelomic (i.e. across a body cavity, e.g. peritoneum).

Five cancers commonly metastasise to bone; these are thyroid, lung, breast, kidney and prostate.

Tumour markers

Some cancers secrete substances into the circulation (Table 6.2).

| Cancer | Marker |

|---|---|

| Prostate | PSA (prostate specific antigen) |

| Colon | CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) |

| Pancreatic cancer | CA19.9 |

| Choriocarcinoma | Beta-HCG |

| Ovarian | CA125 |

| Testicular teratoma | AFP, beta-HCG |

Management

Clinical assessment

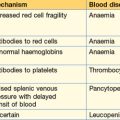

When taking a history and examining a patient who might have cancer it is useful to remember that the disease may present in several ways (Table 6.3).

| Presenting | Examples |

|---|---|

| Problems due to the primary tumour | Haemoptysis from lung cancer |

| Tenesmus from rectal cancer | |

| Visible lump of thyroid cancer | |

| Problems due to a metastasis | Pathological fracture of bone |

| Malignant pleural effusion | |

| Jaundice due to hepatic secondaries | |

| Problems resulting from a substance secreted by the tumour | Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion from lung cancer |

| Polycythaemia due to erythropoietin from a renal cancer | |

| Hypertension due to catecholamines from phaeochromocytoma | |

| General features of malignancy | Weight loss |

| Cachexia | |

| Anaemia | |

| Deep vein thrombosis |

Tumour staging

Staging of a tumour is an attempt to quantify how advanced a cancer has become at the time of diagnosis. Many systems have been devised for different organs and are detailed in the specific chapters. The TNM (tumour, nodes, metastases) system (Box 6.1) is now more widely adopted. This may be divided into a clinical staging or, after pathological assessment, a pathological system (pTNM classification). This system is being constantly updated (the latest revision is TNM7).

Histological grade

Tumour grading is used in conjunction with the TNM to give an assessment of prognosis for the patient (Table 6.4). It also permits evaluation of the efficacy of different treatments on tumours of comparable stage.

| Differentiation | Features |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 – well differentiated | Forms recognisable structures of parent tissue |

| Grade 2 – moderately differentiated | Some degree of organisation |

| Grade 3 – poorly differentiated | Architecture totally disorganised; cells not recognisable from parent tissue |

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant therapy is additional anti-cancer treatment used for some patients thought to have had tumours completely removed by surgery. The aim is to destroy occult micro-metastases by chemotherapy, local radiotherapy or a combination of these. Some patients may not need this treatment and the risks of adjuvant treatment need to be borne in mind in this situation. Adjuvant therapy may be given before (neo-adjuvant therapy) or after surgery (Table 6.5). Useful regression of some tumours (e.g. rectum and breast) can be achieved, converting non-operable into operable disease. Many new trials of different regimes are being performed throughout the world to determine the best treatments.

| Tumour | Adjuvant protocol | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil | Postoperative |

| Methotrexate, mitoxantrone, mitomycin | Postoperative | |

| Radiotherapy or tamoxifen, or both | Postoperative | |

| Oesophagus | 5-Fluorouracil and other agents with or without radiotherapy | Pre- and postoperative |

| Colorectal | 5-Fluorouracil and levamisole | Postoperative |

| Rectum | Radiotherapy | Pre- and postoperative |

| Osteosarcoma | Methotrexate, epirubicin with or without radiotherapy | Pre- and postoperative |

Radiotherapy

There are three ways of administering radiotherapy to kill cancer cells:

Side effects of radiotherapy include local soreness, skin changes and burning, lethargy, nausea and vomiting. Pelvic radiotherapy causes cystitis and diarrhoea. Radiation damage to normal tissues may not become apparent for several years (e.g. radiation enteritis, see p. 129).

Endocrine manipulation

Some tumours are dependent on hormones for their normal growth. Endocrine manipulation may effectively inhibit tumour progression. Examples are shown in Table 6.6.

Table 6.6 Examples of endocrine manipulation which may inhibit tumour progression

| Cancer type | Drug | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | Tamoxifen | Blocks oestrogen receptor binding |

| Anastrazole | Aromatase inhibition (peripheral conversion of oestrogen) | |

| Herceptin | Monoclonal antibody inhibiting cell-membrane receptor protein HER2 | |

| Breast/Prostate | Gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues | Suppression of LH and FSH |

Screening for malignant disease

For a screening programme to be effective, the following points are essential.

• The disease should be common or have defined high-risk groups

• The natural history should be known

• The screening method must be sensitive and specific and able to detect disease early

• Detection methods should be cheap, easy to use and have a high patient compliance

• Effective treatment for early disease should be available

• The screening procedure must not involve hazard to the population tested.