Surgical Management of Pelvic Endometriosis

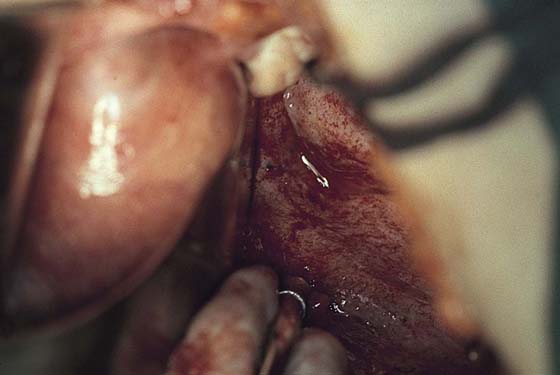

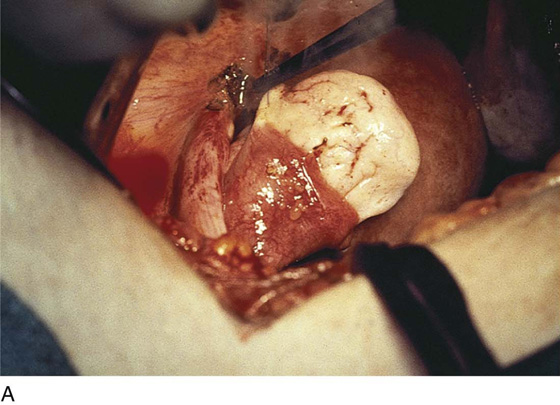

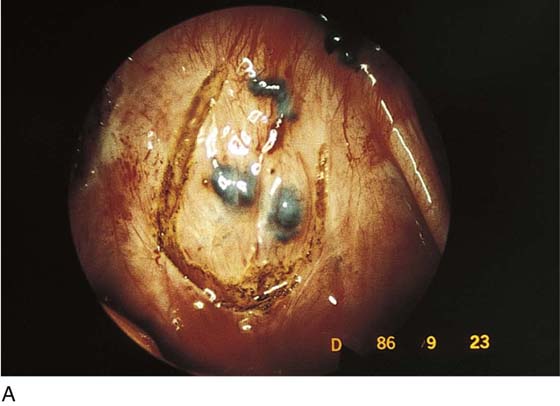

Endometriosis can produce cysts within the ovary as well as reactive adhesions. Endometriosis produces inflammation, sometimes exceedingly severe, in the vicinity of implants (Fig. 25–1). It is curious that the inflammatory response does not necessarily coincide with the severity of endometriosis. The appearance of pelvic endometriosis may likewise assume a variety of patterns, ranging from brownish spots to colorless microcysts (Fig. 25–2A–E).

Endometriosis surgery is performed after attempts at medical therapy have failed to resolve symptoms and eliminate visible lesions. The surgery discussed in this chapter is conservative (i.e., preserves the reproductive organs). The radical treatment strategy is removal of the reproductive organs via hysterectomy, as illustrated in Chapter 11 in Section B. A rather confusing term used indiscriminately is “definitive treatment at surgery.” This phrase typically is used in reference to hysterectomy, but in fact could mean conservative management. Therefore this term would be better eliminated from usage. Surgical removal of the endometriosis with preservation of the uterus and adnexa is accomplished by sharp excision or laser surgery. The best laser for this purpose is the superpulsed carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Another acceptable laser is the KTP-532 fiberoptic laser. The least preferred device is the neodymium yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser because it produces the greatest degree of thermal artifact (coagulation necrosis). Unless otherwise specified, the laser referenced herein will be a superpulsed CO2 laser delivered laparoscopically or directly via handpiece. In strategic areas of endometriosis involvement, injection of sterile water or saline beneath implants creates a heat sink as well as a plane for dissection and serves to protect normal underlying tissue from damage (Fig. 25–3A, B).

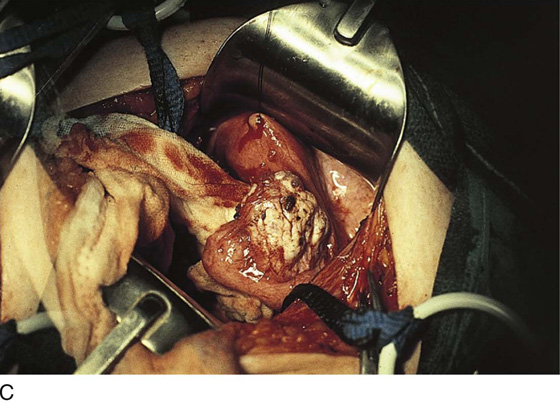

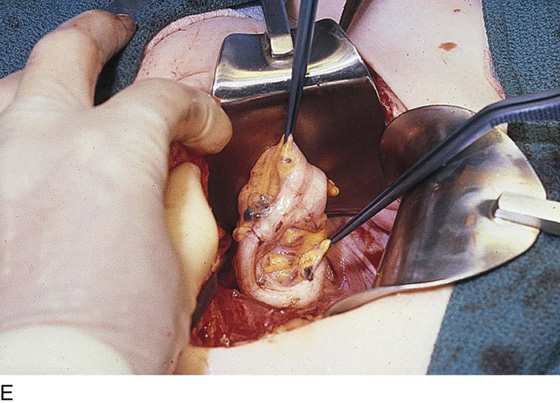

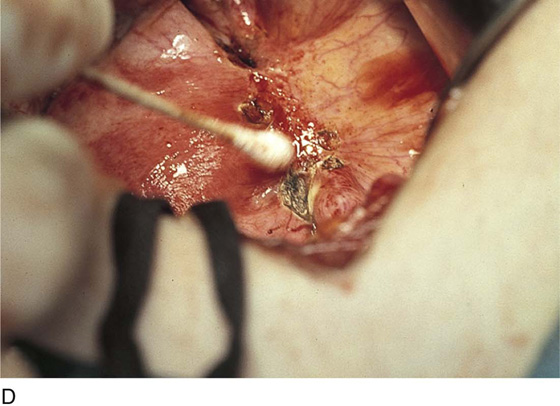

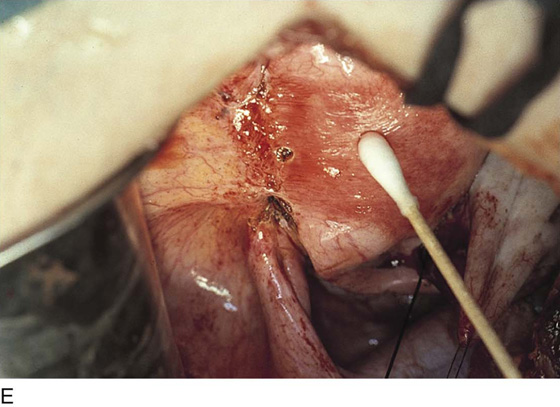

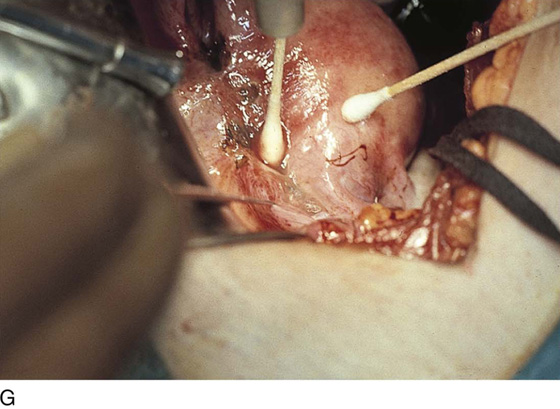

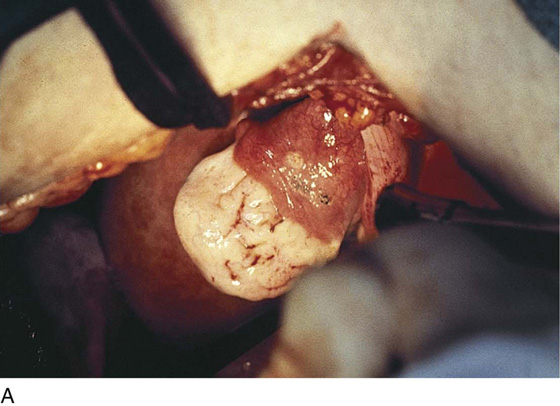

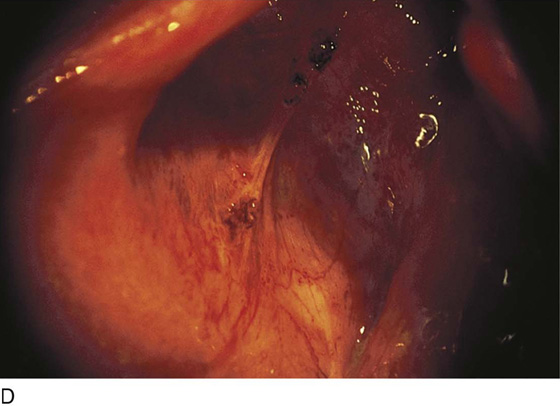

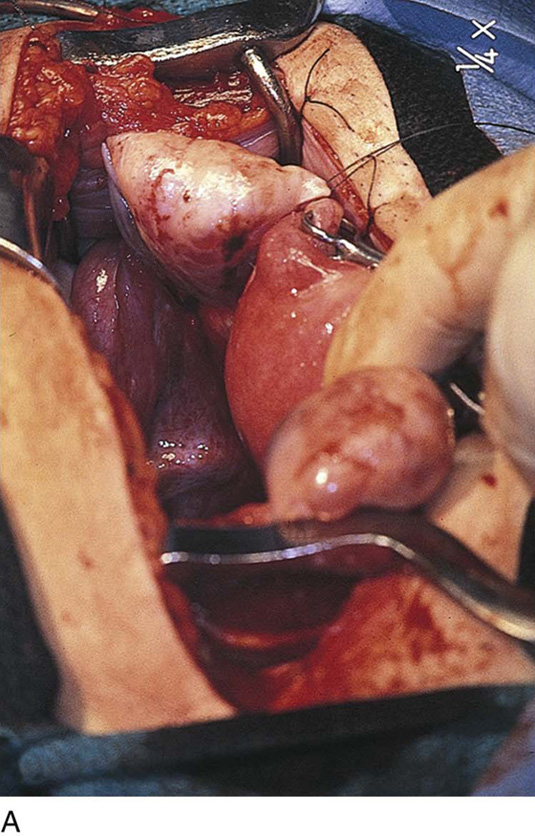

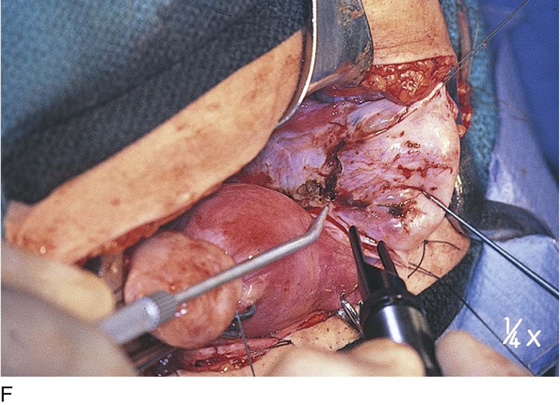

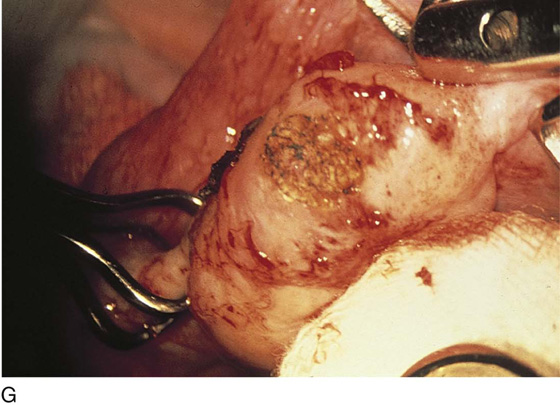

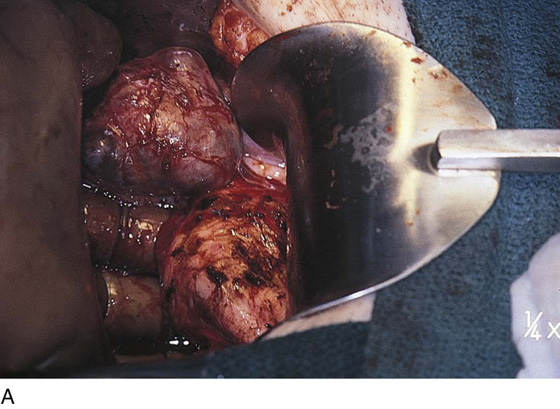

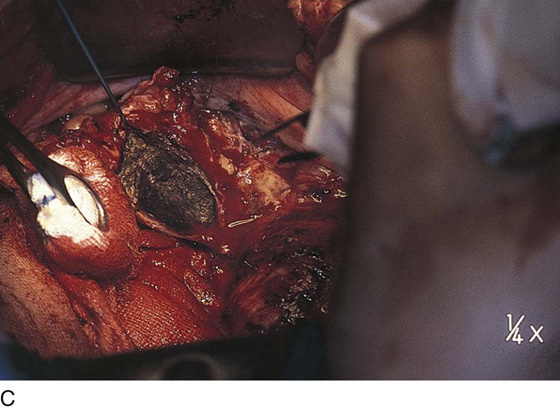

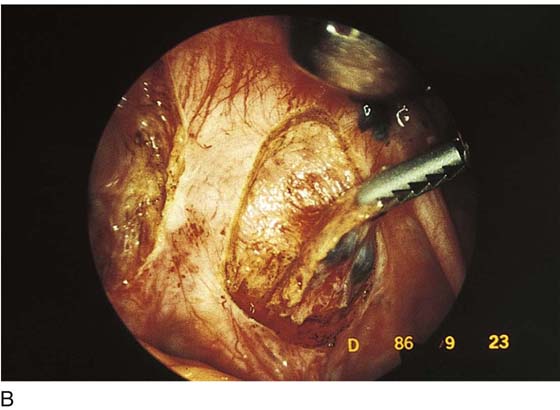

Vaporization of implants is performed at a setting of 5 to 10 W at 100 to 300 pulses/sec and 0.1 to 0.5 msec width with a beam diameter of 1 to 2 mm (Fig. 25–4A–G). When peritoneal or tubal surfaces are to be “brushed” (i.e., very superficially vaporized), power (power density) is reduced sufficiently to permit a single cell layer or a few cell layers to be selectively eliminated (Fig. 25–5A–E). Deeper vaporization or excision may be required. The depth is determined by magnified observation of the wound. As long as siderophagic blood is emitted from the site, endometriosis is present (Fig. 25–6A–G). The most severe cases of endometriosis (stage 4) will require combinations of treatment strategies, including vaporization, excision, adhesiolysis, cystectomy, and possible partial organ excision followed by pelvic reconstruction (Fig. 25–7A–F).

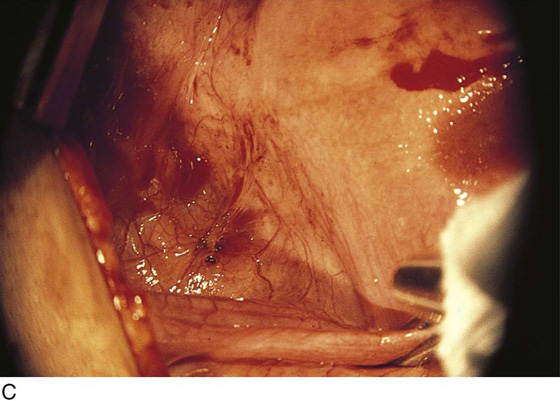

Endometriosis may extend deeply into underlying tissue. In the cul-de-sac, penetration may reach the rectovaginal septum. In these instances, the tissue should be sharply resected by using a combination of laser and scissors (Fig. 25–8A, B).

FIGURE 25–1 Foci of endometriosis deep in the ovarian fossa. Note the extensive inflammatory reaction in the peritoneum surrounding the overt endometrial implants.

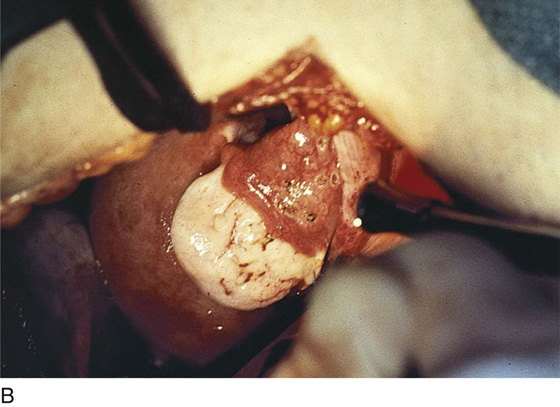

FIGURE 25–2 A. Several biopsy-proven vesicular endometrial implants on the fimbriated portion of the oviduct, which is adhesed to the ovary. B. Detail of cul-de-sac endometriosis. The endometriosis pattern is red with central blue-black implants. C. Characteristic brownish-black endometrial implants on the ovary. D. Close-up of endometriosis of the ovary. As these implants are ablated, brownish (hemosiderin) fluid exits from the lesions. E. Several endometrial implants on the sigmoid colon create dyschezia.

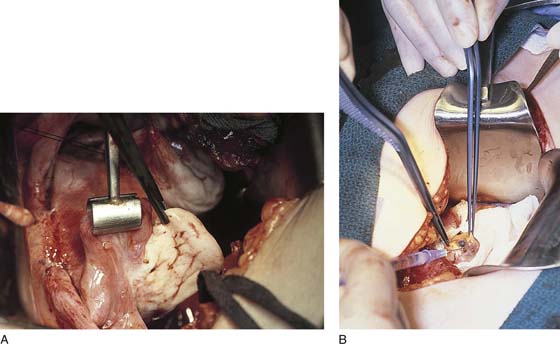

FIGURE 25–3 A. The left adnexa is held in the foreground. To the left, extensive endometriosis involves the urinary bladder. Scar formation resulting from the endometriosis distorts the uterus and the round ligaments, which appear to be inserted into the bladder. B. Sterile water is injected beneath sigmoid colonic endometrial implants with use of a 27-gauge needle. The water creates a heat sink to protect the underlying muscularis and mucosa of the intestine. The same technique is used for bladder endometriosis (see Fig. 25–3A).

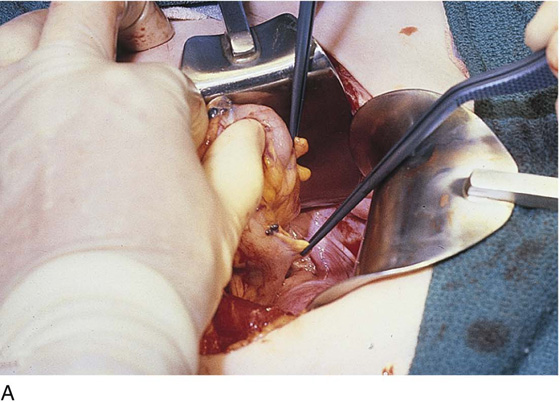

FIGURE 25–4 A. The colon is held in preparation for ablation (in this case) or excision of the endometriosis. B. The endometriosis has been vaporized from the colon (see Figs. 25–2E, 25–3B, and 25–4A). C. The endometriosis of the bladder has been vaporized. Some char is present where the laser altered the implant. Note the right round ligament and the uterus, which are adhesed to the bladder (see Fig. 25–3A). D. Multiple bladder implants have been vaporized. E. Neighboring uterine endometrial implants are vaporized. F. Note the hemosiderin-laden fluid streaming from the round ligament implant. G. The bladder and the uterus are copiously irrigated upon completion of the destruction of all endometriotic implants. The wet cotton-tipped swab extricates any residual char.

FIGURE 25–5 A. The vesicular (pattern) implants on the fimbrial portion of the oviduct have been carefully vaporized (see Fig. 25–2A). B. Upon completion of vaporization, the tube is thoroughly irrigated with normal saline or heparinized Ringer’s lactate. C. Cul-de-sac endometriosis located in close proximity to the ureter. Injection of sterile water beneath the implants will create a plane of dissection and a heat sink. D. The foci of endometriosis have been vaporized (see Fig. 25–5C). E. Close-up view of the vaporization of the implants. The char is irrigated away as the next step in treatment of this disorder.

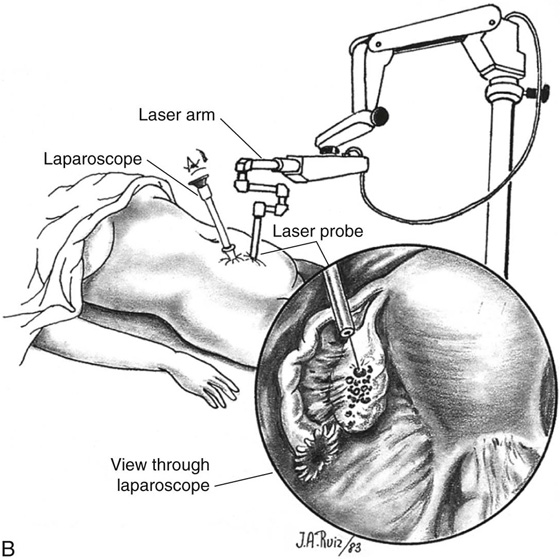

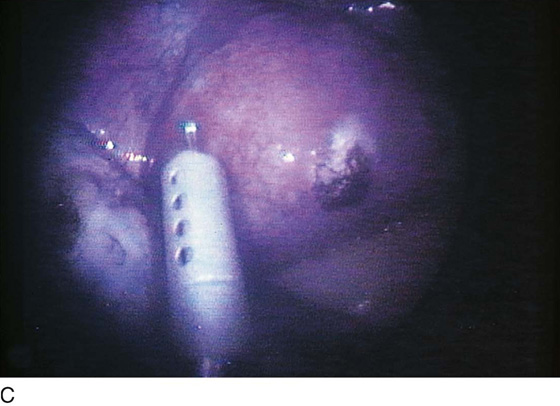

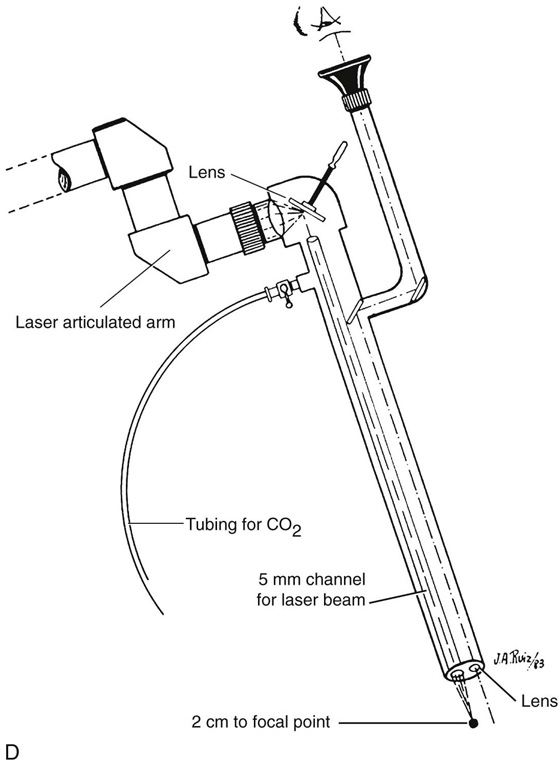

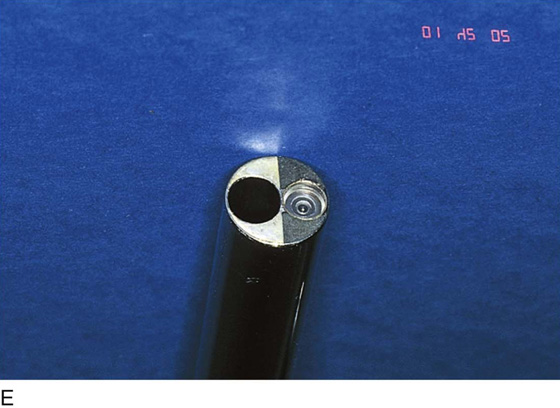

FIGURE 25–6 A. The left ovary not only has surface implants but also is enlarged, suggesting the presence of an endometrial cyst. B. Schema for a second-puncture laser probe and the laparoscopic technique for treating endometriosis. The laser may also be delivered via a wide channel built into the operating laparoscope (so-called single-puncture delivery) (see Fig. 25–6E). C. Laparoscopic view of second-puncture delivery of a fiber laser beam. The laser fiber is placed through an irrigating probe. Thus, irrigation and vaporization are carried out with the same device and require the use of only one of the surgeon’s hands. D. Schema for delivering the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser beam through the operating channel of the laparoscope. In this case, single-puncture delivery integrates the operating tool within a single instrument that is also used to provide light and an optical view of the operative field. E. The terminus of an operating laparoscope for CO2 laser delivery. Note the relative size of the laser channel (left) compared with the optic (right). F. Endometriosis of the ovary is vaporized by a laser handpiece. The probe points to fluid exiting a vaporized implant. G. Close-up of the completed vaporization of ovarian endometriosis.

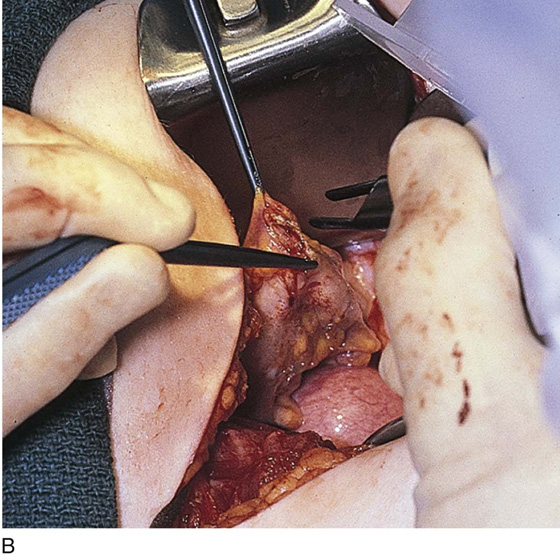

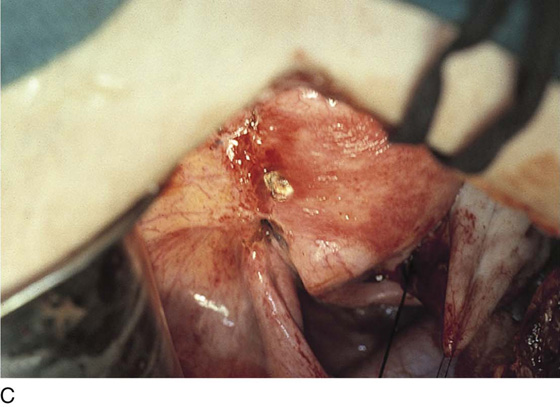

FIGURE 25–7 A. Stage 4 endometriosis. The uterus exhibits multiple implants. The ovaries have bilateral endometrial cysts. The uterus and sigmoid were densely adhesed to the cul-de-sac (these have been dissected free). B. The uterine endometriosis has been vaporized. C. Ovarian deep implants are vaporized. D. An endometrioma has been opened and drained. The walls of the cyst will be resected. E. The resected cyst is held in the surgeon’s hand before it is sent to pathology. F. Approximately half of the treated ovary is conserved. The wound is closed in two layers with 3-0 and 4-0 polydioxanone (PDS) sutures.

FIGURE 25–8 A. Deeply infiltrating endometriosis. The endometriosis has been outlined by a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. (Courtesy Dan Martin, MD.) B. The endometriosis has been sharply excised from the cul-de-sac. (Courtesy Dan Martin, MD.)