Surgical Management of Ovarian Residual and Remnant

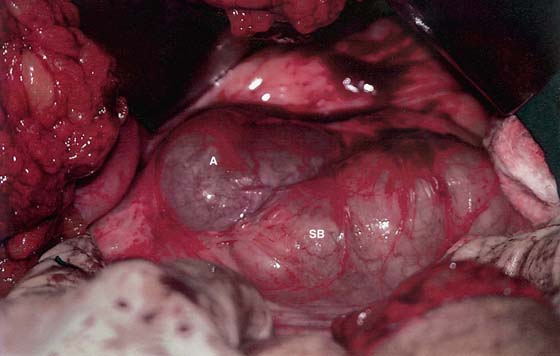

After hysterectomy without salpingo-oophorectomy (bilateral or unilateral), the residual adnexa not uncommonly becomes symptomatic in the form of chronic abdominal pain. The reasons for this pain are myriad but frequently involve adhesions between the residual adnexa attached to the intestines, the bladder, or the peritoneum. The adnexa itself may be completely invested in fibrous tissue and may be densely bound to the pelvic wall in the region of the obturator fossa. Surgery to remove the residual requires careful, gentle, sharp dissection and contemporaneous, compulsive hemostasis. Obviously, precise knowledge of pelvic anatomy is requisite to a successful, noncomplicated outcome. Figure 27–1 illustrates the above points in that distinguishing between hydrosalpinx and intestine may be challenging (Fig. 27–2).

The remnant ovary represents a portion of an ovary that ostensibly had been completely removed at the time of the previous oophorectomy. Obviously, the premise was incorrect because the retained piece of ovarian tissue provides testimony to the fact that the excision of the ovary was not complete.

Pieces of ovarian tissue remaining behind after an incomplete removal of the ovary create significant problems for the unfortunate patient. Typically, these remnants are encased in adhesions, are subjected to a variable blood supply, and create pain.

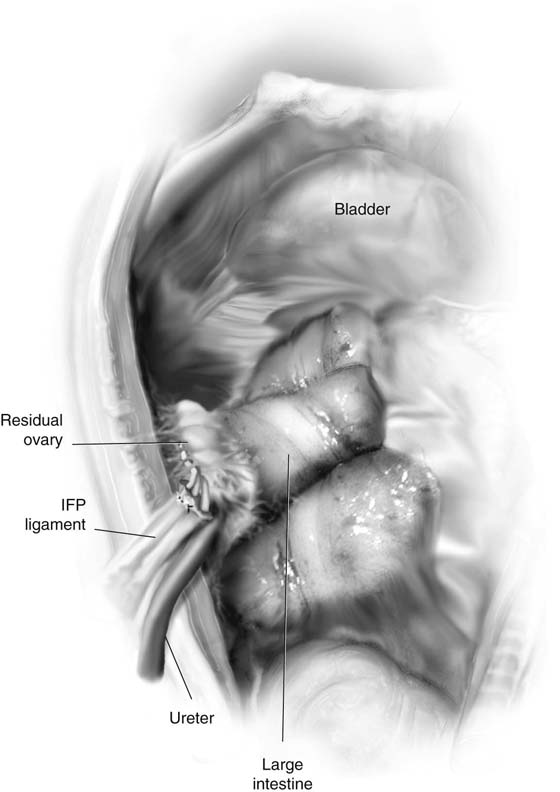

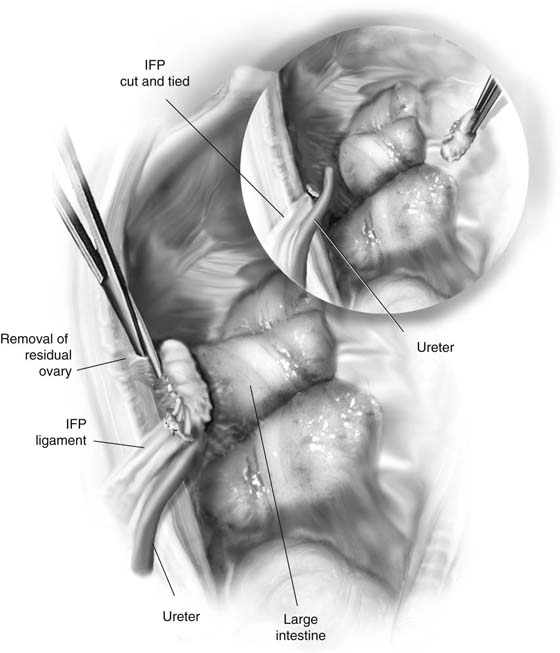

The remnant tissue tends to be plastered to the pelvic sidewall in close proximity to portions of the infundibulopelvic ligament, the ureter, and the external iliac vessels (Fig. 27–3). Not frequently, the large intestine is also tightly adhesed to the ovary. Dissection is performed by gaining retroperitoneal entry to (1) free the intestine from the ovarian tissue, (2) free the ovary from the sidewall structures (above) without damaging those structures, and (3) remove the fragments of ovary and repair the peritoneal defect (Fig. 27–4). The surgeon should not hesitate to consult a urologist to pass a retrograde catheter into the ureter on the affected side.

FIGURE 27–1 Residual ovary and tube seen during laparotomy in a woman with three previous cesarean sections and two subsequent procedures, including a total abdominal hysterectomy. Following extensive adhesiolysis, the right adnexa (A) was exposed deep to the adhesed small intestines (SB). A similar state of affairs was noted on the left. Note the similarity of appearance between the hydrosalpinx and the adhesed small intestine.

FIGURE 27–2 The retroperitoneal spaces were entered over the psoas major muscle, and the right and left ureters were identified. The right and left tubes and ovaries were dissected free of surrounding structures and were removed. Hemostasis was obtained and long tonsil clamps with 3-0 Vicryl suture ligatures were used. The patient had a history of pulmonary embolism; therefore she was given 40 mg of Lovenox 2 hours postoperatively. The removed specimens are seen here. The hydrosalpinx on the left side leaked out when a Babcock clamp was placed onto the tube.

FIGURE 27–3 The remnant ovary is seen adhesed to the colon and sidewall of the pelvis. Note the relationship of the ovarian vessels and ureter to the ovarian mass. IFP, infundibulopelvic ligament.

FIGURE 27–4 The sigmoid colon has been separated from the remnant by sharp dissection coupled with assiduous hemostasis. The ovary is dissected free from the sidewall structure. Inset: The remnant is removed. The course of the ureter is checked and the ureter is carefully examined for any sign of injury. IFP, infundibulopelvic ligament.